Managerial Auditing Journal

The det erminant s of web-based corporat e report ing in France Sabri Boubaker Faten Lakhal Mehdi Nekhili

Article information:

To cite this document:Sabri Boubaker Faten Lakhal Mehdi Nekhili, (2011),"The determinants of web-based corporate reporting in France", Managerial Auditing Journal, Vol. 27 Iss 2 pp. 126 - 155

Permanent link t o t his document :

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02686901211189835

Downloaded on: 25 March 2017, At : 18: 34 (PT)

Ref erences: t his document cont ains ref erences t o 55 ot her document s. To copy t his document : permissions@emeraldinsight . com

The f ullt ext of t his document has been downloaded 1071 t imes since 2011*

Users who downloaded this article also downloaded:

(2011),"Determinants of corporate reporting on the internet: An analysis of companies listed on the Istanbul Stock Exchange (ISE)", Managerial Auditing Journal, Vol. 27 Iss 1 pp. 87-104 http:// dx.doi.org/10.1108/02686901211186117

(2010),"Determinants of corporate internet reporting: evidence from Egypt", Managerial Auditing Journal, Vol. 25 Iss 2 pp. 182-202 http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02686901011008972

Access t o t his document was grant ed t hrough an Emerald subscript ion provided by emerald-srm: 602779 [ ]

For Authors

If you would like t o writ e f or t his, or any ot her Emerald publicat ion, t hen please use our Emerald f or Aut hors service inf ormat ion about how t o choose which publicat ion t o writ e f or and submission guidelines are available f or all. Please visit www. emeraldinsight . com/ aut hors f or more inf ormat ion.

About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com

Emerald is a global publisher linking research and pract ice t o t he benef it of societ y. The company manages a port f olio of more t han 290 j ournals and over 2, 350 books and book series volumes, as well as providing an ext ensive range of online product s and addit ional cust omer resources and services.

Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation.

*Relat ed cont ent and download inf ormat ion correct at t ime of download.

The determinants of web-based

corporate reporting in France

Sabri Boubaker

Groupe ESC Troyes, Troyes & Universite´ Paris Est, IRG, Cre´teil, France

Faten Lakhal

Universite´ Paris Est, IRG, Cre´teil, France and ISG-Universite´ de Sousse,

Sousse, Tunisia, and

Mehdi Nekhili

Rouen Business School, Mont-Saint-Aignan,

France and Universite´ de Reims Champagne-Ardenne, Reims, France

Abstract

Purpose– The purpose of this paper is to consider the determinants of web-based corporate reporting by French-listed firms.

Design/methodology/approach– The paper is based on a literature review of the determinants of web-based corporate disclosures and is both descriptive and explicative. It analyzes the use of the internet to disseminate corporate information and examines the extent of web-based corporate disclosure by developing a set of disclosure indexes. To test the authors’ hypotheses, an OLS regression framework was estimated on a sample of 529 French-listed firms in 2005.

Findings– Descriptive analysis shows that French firms are using the internet to disseminate existing rather than timely information. The results show that large-sized firms, large-audited firms, firms featuring a dispersed ownership structure, those that have issued bonds or equities and IT industry firms extensively used the web to disclose information to their shareholders. The results also show that voluntary disclosures are more suited for the internet than mandatory disclosures. Research limitations/implications– The study does not cover all information provided on web sites, particularly those about the impact of IFRS on companies’ accounts.

Practical implications– The findings are useful to both managers, wishing to meet actual and potential investors’ informational needs and to investors wishing to invest in a richer informational environment and to better assess firm value.

Originality/value– This paper provides a better understanding of the choice of the internet to release information in the French context, where internet corporate reporting is not standardized as in the USA and Canada.

KeywordsFrance, Disclosure, Internet, Financial reporting, Corporate reporting, Disclosure index, Voluntary disclosure

Paper typeResearch paper

Introduction

The adoption of the internet as a global practice for the dissemination of financial information is common for an increasing number of publicly listed firms around the world. Jones and Xiao (2003) reported in a forward-looking study that the internet is becoming more and more important in disseminating corporate information in the near future. The internet creates a new reporting environment for listed firms willing to continuously communicate with existing shareholders and to attract potential ones. The benefits of this fast-growing phenomenon include the ease of access, the

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/0268-6902.htm

MAJ

27,2

126

Received 24 October 2010 Revised 30 November 2010 Accepted 18 February 2011

Managerial Auditing Journal Vol. 27 No. 2, 2012 pp. 126-155

qEmerald Group Publishing Limited 0268-6902

DOI 10.1108/02686901211189835

widespread diffusion, the savings of costs associated with printing and sending paper-based reports and the rapid comparison and analysis of data. The internet also meets shareholders’ needs to handle an ever-expanding information environment. The dissemination of financial information via the internet has no hard or fast rules or guidelines, which creates a large range of reporting practices across firms.

One of the initial studies on web-based corporate disclosure is that carried out by Petravick and Gillet (1996). They find that more than half of the studied firms have a web site among which many include financial information. This shows that companies regard the internet as an important medium to disseminate financial information. Several other subsequent studies show that the internet is nowadays the main mode used to release and update corporate financial information in a timely fashion (Ashbaughet al., 1999; Brennan and Hourigan, 2000; Craven and Marston, 1999; Ettredgeet al., 2001; Debrecenyet al., 2002; Marston and Polei, 2004; Xiaoet al., 2004; Alyet al., 2010). Moreover, Jones and Xiao (2003) have predicted the increased use of the internet to disseminate information.

This paper is concerned with the determinants of web-based financial reporting by French-listed firms. The choice of the French context is motivated by three concerns. First, to the best of our knowledge, no prior studies have been published on the use of the internet by French companies to disclose information, although this communication means is highly recommended by the Autorite´ des Marche´s Financiers (AMF, which is the equivalent of the SEC on the USA). Second, the French environment is worth studying given the type of firms’ ownership structures. French firms are mostly held by families or by controlled shareholders, unlike US firms where ownership structure is much more dispersed among the public. The motivation then to disclose information by these two types of firms is deemed to be different. Last, this paper provides a better understanding of the choice of the internet to release information in the French context, where internet corporate reporting is not standardized as in the USA and Canada.

A comprehensive set of items is used to fully capture the extent of information disclosure via the internet. These items are used to form several indexes representing various facets of web-based disclosure (e.g. content, presentation format and incremental information). The presentation dimension is important because it improves the timeliness and promotes the understandability of information released on firms’ web sites (Debrecenyet al., 2002). Internet financial reporting is considered by the AMF[1] as offering new opportunities to firms to supplement their mandatory financial disclosures with additional voluntary information and to facilitate the distribution of corporate information to shareholders. The AMF underlines the use of the internet by French firms to complement traditional reporting means and not merely to disclose already-existing printed-paper information. We then develop a score measuring the incremental information disseminated only on web sites.

The purpose of the current study is descriptive and explanatory. Unlike the first wave of previous studies that focus mainly on disclosure practices (Brennan and Hourigan, 2000; Craven and Marston, 1999; Debreceny and Gray, 2001; Delleret al., 1999; Pirchegger and Wagenhofer, 1999), this study focuses on items disclosed on web sites. It also develops different scores of web-based disclosures to identify the determinants of the extent of internet financial reporting in France. The results show that the use of the internet varies significantly across French-listed firms. These companies include mandatory and voluntary disclosures to their web sites. The score

Corporate

reporting

in France

127

of voluntary information has the greatest explanatory power than other scores, suggesting that web sites are more suited for voluntary information to meet investors’ specific needs in terms of content and structure. However, the incremental information disseminated on web sites beyond printed-forms is relatively weak, suggesting that French companies regard paper-based disclosures as the primary channel to disseminate information. The findings also show that the extent of web-based corporate disclosures are positively associated with firm size, audit size, free float, capital or debt issuance and are higher for IT firms. These results are consistent with the existing literature and support in part our hypotheses.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. The second section presents a review of the internet financial reporting literature. The third section highlights the determinants of web-based financial disclosures. The fourth section describes the sample selection procedure, the disclosure index construction and the research methodology. Empirical findings and discussions are presented in the fifth section. The last section concludes the paper.

Internet financial reporting literature

Recently, there has been a dramatic increase in the use of the internet to disseminate corporate information. While the acceptance of internet disclosures has increased, most of the information provided by this means has already appeared in printed form (Debreceny and Gray, 2001). However, the internet affords companies with an additional opportunity to disseminate information through another medium, since it reduces boundaries for generating information. Furthermore, it provides firms with a new reporting environment broadly for information releases, with many implications for the content and the presentation features of the reported information (IASC, 1999). The extensive use of the internet to disclose investor-related information encourages major regulators to develop systems for filing information. The earliest one is EDGAR adopted by the SEC in the USA, followed by the SEDAR established by the Canadian Securities Administrators and CDS Inc. in Canada[2]. As an attempt to standardize internet reporting, US and Canadian companies have to register their financial reports on the internet through these systems. Abdelsalamet al.(2007) show that even with the new regulatory environment in the UK and EU, aimed at enhancing the credibility of financial reporting; there is much improvement in internet corporate reporting by British companies in regard to credibility of information. In France, the AMF recognizes the increasing importance of the internet to disseminate financial information in the 1998-2005’s recommendation, which is the most important French regulatory initiative related to internet reporting issues. It suggests that information disclosed on web sites should be sincere, exact and precise. Companies should also ensure that web-disseminated information reaches wider audience in a timely fashion. Even the existence of some attempts to provide a uniform and standardized system for web-based disclosures (e.g. EDGAR and SEDAR), financial reporting on the internet is still a result of various practices. Xiaoet al.(2004) argue that the unregulated nature of web-based disclosures raises security issues since it prevents users from assessing the quality of the retrieved information.

A growing number of empirical studies throughout the world have examined the role of internet to disseminate corporate information. This literature falls into three types of categories: descriptive, comparative and explanatory.

MAJ

27,2

128

Descriptive research focuses on the number of firms using the web as a medium to disseminate information and to which extent these firms include financial information on their web sites. Petravick and Gillet (1996) show that 69 percent of the 150 largest firms forming theFortune 500 have a web site and that 81 percent of these firms include financial information on their web sites. Other studies stress on the growing use of the internet for disclosing financial information rather than marketing purposes. Gowthorpe and Amat (1999) examine 379 Spanish companies and reported that only 19 percent have web sites, and that 55.7 percent of these companies provide financial information on their home page. Ettredgeet al.(2001) focus on the nature of financial information of 490 US firms and show that larger and high-tech companies are likely to provide more information than other firms.

Another research stream compares web-based disclosure across countries. Delleret al. (1999) analyze investor-related information included on web sites of US, UK and German companies in 1998. They show that, respectively, 91, 72 and 71 percent of US, UK and German firms use internet financial reporting. Geeringset al.(2003) examine the top 50 companies from Belgium, France and The Netherlands. They report more developed internet practices in France and The Netherlands than in Belgium. A more recent comparative study – on five countries covering Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, the UK and the USA – was carried out by Allam and Lymer (2003). They show that 96 percent of studied firms publish a number of financial items including balance sheets, profit and loss accounts and cash flow reports. The findings of these studies shed light on significant differences in internet practices across countries. However, they provide little theoretical background for their analysis and do not consider practice differences within one country.

The third category of research is explicative and examines the determinants of such practices. Ashbaughet al.(1999) examine a sample of 290 US firms and find that large and more profitable firms are more likely to use the internet for financial reporting purposes. As for Debrecenyet al.(2002), they find that voluntary adoption of internet disclosure in 22 countries is influenced by firm size and US listing, but not by leverage. In the UK, Craven and Marston (1999) report a significant relationship between size and financial disclosures on the web[3]. Oyelereet al.(2003) find that size, liquidity, industry sector and ownership dispersion are the major determinants of web-based disclosure practices in New Zealand. Recently, Kelton and Yang (2008) show that US firms with a large proportion of independent directors and audit committee members are more likely to engage in internet financial reporting.

Some authors refine further the analysis by distinguishing between mandated and non-mandated disclosed items (Ettredgeet al., 2002; Xiaoet al., 2004). Marston and Polei (2004) distinguish between presentation format features and disclosure content. They examine a sample of German-listed companies and show that firm characteristics are strongly associated with the content dimension of web-based disclosures and to a lesser extent to the presentation format. More recently, Alyet al.(2010) show that in the case of Egyptian-listed companies, profitability, foreign listing and industrial type are the factors most affecting the content and the presentation format of internet financial reporting.

The determinants of web-based financial reporting

Theoretical and empirical studies on information disclosure predict and show that voluntary disclosures improve stock market liquidity and mitigate the effects

Corporate

reporting

in France

129

of information asymmetry on the cost of capital (Leuz and Verrecchia, 2000; Busheeet al., 2003). This literature focuses primarily on voluntary reporting through traditional paper form releases. As internet financial reporting is unregulated, it can be viewed as a component of company voluntary disclosure practices (Ashbaughet al., 1999). Two major theories are deemed to explain voluntary disclosure policies. The first one is agency theory, suggesting that corporate disclosure is important in mitigating agency costs ( Jensen and Meckling, 1976). Second is signaling theory, stating that highly performing managers use corporate disclosure to distinguish themselves from those who perform poorly (Milgrom, 1981). The cost-benefit hypothesis is also used in the extant literature to explain disclosing decisions (Leuz and Verrecchia, 2000). According to this hypothesis, when disclosure benefits exceed its costs, voluntary disclosure would be more profitable for managers.

The determinants of the extent of financial reporting on the internet described below have been identified from the voluntary disclosure literature. We choose to focus on determinants that are more likely to influence the broaden access of corporate disclosure on web sites.

Firm size

Several studies show that firm size is positively associated with corporate disclosure (Lang and Lundholm, 1993; Kaszniket al., 2001). Agency theory suggests that large firms exhibit higher agency costs due to the information asymmetry between market participants ( Jensen and Meckling, 1976). To reduce these agency costs, larger firms disclose a large flow of corporate information. According to the political cost hypothesis, large firms are more publicly visible which attracts more financial analysts putting firms under higher pressure. Moreover, Raffournier (1995) suggests that firms reporting regular financial information experience less disclosure costs than do small firms.

With low incremental costs, large firms are more likely to supplement traditional financial disclosure with internet reporting to benefit from decreasing agency costs. The benefits of such disclosures are increasing with firm size (Oyelereet al., 2003). A number of other studies support the existence of a positive relationship between firm size and both the use and the extent of internet financial reporting (Ettredgeet al., 2002; Marston and Polei, 2004; Xiao et al., 2004). The foregoing discussion suggests the following hypothesis:

H1. There is a positive relationship between firm size and the extent of internet corporate reporting.

Ownership dispersion

Agency theory provides insights into the relationship between disclosure behavior and ownership structure ( Jensen and Meckling, 1976). Corporate disclosure is considered as one means to control the agency costs arising from conflicts of interests between insiders and outside shareholders. The corporate finance literature focuses on mitigating conflicts of interests between incumbent managers and shareholders due to the separation between ownership and control. Managers in France are very often members of the controlling family which exacerbates the potential conflicts between the controlling manager and minority shareholders (Shleifer and Vishny, 1997). This situation may suffer from the low legal protection environment of external investors that characterizes civil law countries, such as in France (La Portaet al., 1998).

MAJ

27,2

130

Ownership structure is likely to influence financial disclosures. The accounting literature suggests that the reporting incentives of managers affect both the production and the quality of accounting information. This relationship was documented in several studies (Eng and Mak, 2003; Ho and Wong, 2001; Healy and Palepu, 2001). As share ownership is concentrated, large shareholders are far more able to obtain private information due to the relatively weak demand for public disclosure in comparison to widely held companies. In respect of internet financial reporting, the broad dissemination of information reduces information asymmetry between insiders and outside shareholders. Given the incentives of large shareholders to retain information, the use of the internet in concentrated ownership structures is much more for promoting company products rather than for information disclosure purposes. Pirchegger and Wagenhofer (1999), Oyelereet al.(2003) and Kelton and Yang (2008) found that the degree of financial reporting on the internet increases with ownership dispersion supporting the agency theory hypothesis. The preceding discussion leads to the following hypothesis:

H2. There is a positive relationship between ownership dispersion and the extent of internet corporate reporting.

Firm performance

Analytical literature, mainly based on Verrecchia (1983) and Dye (1985) models, predicts that managers would prefer releasing only information which will increase current firm value. Besides, under the signaling theory hypothesis, profitable firms have the incentive to distinguish themselves from less profitable ones in order to attract more capital (Grossman and Hart, 1998). Corporate disclosure aims at increasing firm value and reducing the risk of being undervalued by the market. Empirical literature on voluntary disclosures has tested these predictions and found mixed results. Depoers and Jeanjean (2010) show a negative relationship between information withholding and firm performance. They argue that well doing firms incur high costs of withholding information. This is likely to lead managers to disclose information. Firms that report large earning increases have incentives to enhance disclosure both prior to and concurrent with the earning realization (Lang and Lundholm, 1993; Baginskiet al., 2002). However, Skinner (1994) suggests that firms disclose voluntarily their earnings to inform the market about negative news to reduce legal liability.

In respect of web disclosures, Pirchegger and Wagenhofer (1999) and Aly et al.

(2010) find that the relationship between internet reporting and firm profitability was supported for Austrian and Egyptian companies, respectively. This result is not in line with those find by Ashbaughet al.(1999) and Ettredgeet al.(2002) on US samples, by Xiaoet al.(2004) for the Chinese companies and by Oyelereet al.(2003) in New Zealand. The results of previous studies either on paper-based voluntary disclosures or on web-based financial reporting are mixed; accordingly, no directional relationship can be conjectured. The discussion here suggests the following hypothesis:

H3. There is a relationship between firm performance and the extent of internet corporate reporting.

Cross-listing

Cross-listing is likely to enhance the disclosure level of a firm. Foreign investors are likely to be more cautious about the monitoring of management in order to protect

Corporate

reporting

in France

131

themselves against information asymmetry between managers and external shareholders. In addition, they contribute to the adoption of international standards and ensure that companies disclose wide information to the market. Several researches use the foreign listing as an important factor to explain the corporate disclosure policy because it constrains managers to enhance the level of their disclosures. These studies show that firms listed on foreign markets are likely to release more comprehensive information than those listed on the local market only (Wallaceet al., 1994; Raffournier, 1995; Fergusonet al., 2002).

Given the temporal information asymmetry faced by foreign investors with paper-based disclosures, internet financial reporting provides foreign investors with timely and extensive information at low costs (Ashbaugh et al., 1999; Craven and Marston, 1999; Oyelereet al., 2003; Debrecenyet al., 2002). Firms listed on foreign markets are more inclined to disclose additional information to benefit from higher levels of liquidity and to reduce their cost of capital. They would adopt internet financial reporting to create a greater level of transparency and compete with other local-listed firms to raise capital at a low cost (Debrecenyet al., 2002; Xiaoet al., 2004; Alyet al., 2010). Traditional financial reporting based on paper form disclosure is expensive and could not reach rapidly foreign investors allowing them to transact on a timely manner as with internet financial reporting. The relationship between cross-listing and internet financial reporting is then expected to be positive:

H4. There is a positive relationship between cross-listing and the extent of internet corporate reporting.

Audit size

Agency theory explains and predicts that auditing helps mitigate agency costs due to the interest conflicts between manager and shareholders. Big auditors are likely to be independent and could constrain managers to maintain more stringent disclosure standards (DeAngelo, 1981). Large audits demand high-quality disclosure. This statement could be explained by the signaling hypothesis because managers that hire large auditing firms signal to the market that they are willing to provide quality disclosures (Healy and Palepu, 2001). Researchers have shown the existence of a positive relationship between the use of large audit firms and voluntary disclosures. Large audit firms may encourage companies to enhance the precision, the quality and the credibility of the disclosed information to preserve their reputation. Depoers (2000) has shown that French-listed firms audited by one of the Big Six firms disclose more information than those audited by less-known auditors. Given that disclosures on the firm’s web site is a signal of extensive disclosure policies, signaling and agency theories predict a positive relation with large audit firm. Xiaoet al.(2004) argue that large audit firms (especially the Big Fours) are more inclined to encourage the use of innovative practices such as internet financial reporting where Alyet al.(2010) show that audit size does not explain corporate internet reporting by Egyptian companies. Overall, this new channel of disclosure offers a guarantee against the loss of control of information disclosed on the web.

In France, at least two ( joint) auditors are required by law for listed companies. In our study, we use a dichotomous variable coded “1” if at least one of the two statutory auditors is a Big Four accounting firm and “0” otherwise. This is expressed into the following hypothesis:

MAJ

27,2

132

H5. There is a positive association between audit size and internet financial reporting practices.

Leverage

Companies can reduce agency costs of debt by enhancing their corporate disclosure level. According to the free cash flow hypothesis ( Jensen, 1986), managers are likely to invest freely available cash flows in negative net present value projects. Shareholders will then force entrepreneurs to have enough accumulated debt to reduce the cash available at the discretion of managers. Voluntary disclosures help reduce the conflicts of interests between debt holders and shareholders ( Jensen and Meckling, 1976). As debt increases, further initiatives such as internet financial reporting help mitigate the problems of high debt and ensure the informational needs of debt holders. The findings of Lang and Lundholm (1993), Fergusonet al.(2002) and Xiaoet al.(2004) support this argument.

However, some authors show a negative relationship between voluntary disclosure and debt level (Wallaceet al., 1994; Eng and Mak, 2003). Firms with high debts are more likely to provide debt holders with more private information, which decreases the need for additional public disclosures. In addition, the agency costs of free cash flow could be controlled by debt, which plays here a substitutive role for the monitoring of management. As a consequence, the control effect of debt shrinks the control effect of voluntary disclosure. The relationship between internet disclosure and leverage was not supported by Debrecenyet al.(2002) and Brennan and Hourigan (2000) who find that voluntary adoption of internet corporate disclosure is not associated with leverage. As the relationship between corporate disclosures including information disseminated on the web is not conclusive, we propose the following non-directional hypothesis:

H6. There is a relationship between leverage and the extent of internet corporate reporting.

IT Industry

The industry type affects disclosure choices, especially when the reported information is specific to the firm itself and not common to the industry (Dye and Sridhar, 1995). Wallaceet al.(1994) suggest that industry effects could explain the different levels of disclosure among firms. The voluntary disclosure literature shows that firms from some industries disclose more information than other industries. In particular, companies belonging to the IT industry are more inclined to disclose regular and additional information because they are exposed to a larger than average risk of price fluctuations leading them to constantly report information (Fergusonet al., 2002). In addition, these firms are likely to adopt internet web-based reporting to show that they are technology leaders (Xiaoet al., 2004). They could provide users with more sophisticated levels of technology and innovation in a manner that improves the access and the presentation format of the information. High-tech companies have also the expertise to assimilate and use internet more easily than companies from other industries. Finally, the future prospects of these companies are not predictable given that these firms are subject to rapid changes and turbulent environment. Debreceny et al. (2002) argue that the diffusion of information through internet could provide a versatile, regular and instantaneous dissemination of information, timely enough for decision making.

Corporate

reporting

in France

133

Evidence supporting the existence of an industry type effect was provided by a number of studies. In concern with internet reporting, Brennan and Hourigan (2000) and Xiaoet al.(2004) find that industries that are more technologically advanced than others disclose more information through their web sites than do firms from other industries. Other studies show a significant association between the extent of financial information on the web and industrial classifications (Ettredgeet al., 2001; Debrecenyet al., 2002). The discussion above leads to the following hypothesis:

H7. There is a positive relationship between IT industry and the extent of internet corporate reporting.

Equity offering

The increase in share capital indicates that additional funds were raised through issuing company’s shares or debts. The change in equity and debt shows the extent of the need to raise external finance (Clarkson et al., 1994). Prior to equity offering, companies engage in voluntary disclosure policies. Managers are likely to disclose positive information about firm performance when they need external capital. Since the lack of information could be interpreted as a negative signal, managers will display all information to avoid adverse selection prior to raise external finance. The relationship between equity offering and corporate disclosures was supported in the literature by Lang and Lundholm (1993). These authors show that US companies that access the capital markets are more likely to disclose regular information. Prior studies supporting this relationship include Clarksonet al. (1994) and Frankelet al. (1995). Assuming that internet financial reporting, as with other reporting sources can be informative to external shareholders, we expect the incentives to be the same for web site dissemination of information. This is expressed in the following hypothesis:

H8. There is a positive relationship between raised share capital and the extent of internet corporate reporting.

Sample description and variable measurement Sample selection

We start with the sample of all French-listed firms appearing in the Worldscope database in 2005. We exclude financial and banking firms (SIC codes between 6000 and 6999) because they are subject to specific disclosure requirements. We rule out firms introduced, delisted, merged or acquired during 2005 and those with missing financial data. There are 16 firms with web sites that are under construction or inaccessible and 39 with no web site. Eliminating all these firms leaves us with a sample of 529 firms. Web sites were visited between October and November 2005. The web sites of the sample firms were located on the AMF web site, in the Worldscope database, or on the Google search engine. Accounting and financial data were collected from Thomson Financial database and information on the free float was hand-collected from annual reports (Table I).

Table II shows the distribution of sample firms across industries using Campbell’s (1996) grouping and presents the percentages of firms having web sites by industry. All petroleum and construction firms have web sites while this figure is as low as 72.97 percent for the food and tobacco industry. Table II shows that 93.12 percent of the sample firms use internet as a medium to disseminate information to investors.

MAJ

27,2

134

This percentage is relatively high compared to that found in other European countries by Petravick and Gillet (1996) and Gray and Debreceny (1997) with, respectively, 69 and 60 percent. This finding stresses on the recent growing use of internet for information dissemination.

Number of firms

Number of firms in the Worldscope database (2005) 982

Subtract

Financial and banking firms (SIC codes 6000-6999) 173 Firms introduced, delisted or merged during 2005 66

Firms with missing financial data 159

Firms with web sites that are under construction or could not be opened 16

Final sample 568

Firms with no web site 39

Firms with an active web site 529

Notes:Our sample consists of all French-listed firms appearing in the Worldscope database in 2005; we exclude all financial and banking corporations (SIC codes 6000-6999); we exclude firms introduced, delisted or those that merge during 2005; we discard also firms with missing financial data and we restrict our analysis to firms with functioning web sites during October-November 2005

Table I. Sample selection procedure

The industry classification of the sampled firms based on Campbell (1996) All sampled firms Firms with a web site SIC codes Number % Number % Within industry (%)

Petroleum 13, 29 6 1.06 6 1.13 100.00

Consumer

durable 25, 30, 36, 37, 50, 55, 57 112 19.72 103 19.47 91.96 Basic industry 10, 12, 14, 24, 26, 28, 33 64 11.27 60 11.34 93.75 Food and

tobacco 1, 2, 9, 20, 21, 54 37 6.51 27 5.10 72.97 Construction 15, 16, 17, 32, 52 31 5.46 31 5.86 100.00 Capital goods 34, 35, 38 66 11.62 64 12.10 96.97 Transportation 40, 41, 42, 44, 45, 47 16 2.81 14 2.65 87.50 Unregulated

utilities 46, 48 26 4.58 24 4.54 92.31

Textile and

trade 22, 23, 31, 51, 53, 56, 59 50 8.80 44 8.32 88.00 Services 72, 73, 75, 76, 80, 82, 87, 89 138 24.29 136 25.71 98.55 Leisure 27, 58, 70, 78, 79 22 3.88 20 3.79 90.91

Total 568 100 529 100 93.12

Notes: This table shows the distribution of sampled firms across industries and reports the percentage of firms with a web site by industry category; the industrial classification is based on Campbell (1996); industries are defined as follows: petroleum (SIC 13, 29), consumer durables (SIC 25, 30, 36, 37, 50, 55, 57), basic industry (SIC 10, 12, 14, 24, 26, 28, 33), food and tobacco (SIC 1, 2, 9, 20, 21, 54), construction (SIC 15, 16, 17, 32, 52), capital goods (SIC 34, 35, 38), transportation (SIC 40, 41, 42, 44, 45, 47), unregulated utilities (SIC 46, 48), textiles and trade (SIC 22, 23, 31, 51, 53, 56, 59), services (SIC 72, 73, 75, 76, 80, 82, 87, 89) and leisure (SIC 27, 58, 70, 78, 79)

Table II. Sample distribution across industries

Corporate

reporting

in France

135

Disclosure index

A disclosure checklist was compiled on the basis of the existing literature by Xiaoet al.

(2004), Marston and Polei (2004), Debreceny et al. (2002), Deller et al. (1999) and Pirchegger and Wagenhofer (1999). The developed disclosure index is composed of a comprehensive checklist of 101 items and is computed for all the 529 sampled French firms. These items encompass the two components of web reporting, namely the content information (69 items) and the presentation format features (32 items). The content score measures information is provided on web sites which are divided into three categories:

(1) general information (eight items) and investor-related information (17 items); (2) financial information (25 items); and

(3) corporate governance (nine items) and corporate and social responsibility (six items).

The presentation format features refer to the use of specific advantages offered only by the internet to add more value to the disclosed information (Ettredgeet al., 2002). The presentation format score is composed of 26 user-friendly and technology items. These include, among other, the use of English language, search engines, frequently asked questions, hyperlinks and the use of specific file format. The presentation dimension is important because it encompasses the timeliness device which is likely to improve the quality of disclosed information (Debreceny et al., 2002). We record seven items referring to timeliness.

We compute a disclosure index score for all our sample firms by assigning a point for each of the 101 items when disclosed on the firm’s web site. Each item takes a value of 1 if it is disclosed and 0 otherwise. To avoid multiple counting, we assign only one point even if the item appears more than once on the firm’s web site. This dichotomous basis has been used in prior studies by Cooke (1989). The total score is calculated as an unweighted sum of the scores of each item which assumes their equal importance[4]. Following Xiaoet al.(2004), we distinguish between current year information and past years’ information. Internet reporting is not only a matter of timely information; a potential investor needs also historical information to better assess firm value. Additional items with regard to corporate governance issues in France were included for the calculation of the content score such as the audit and remuneration committees and the information about director’s dealing. As Ettredgeet al.(2002), the content score was divided into a mandatory score and a non-mandatory score to better characterize the extent of web-based disclosure.

Unlike previous studies, we distinguish between paper-based financial disclosures and disclosures made only on the web. The internet offers new opportunities to present and communicate information to the market in addition to being a medium used by companies to provide investors with a copy of paper-based annual reports. We then use an incremental information score calculated as the additional information provided on the web relatively to what exists in the printed forms of corporate reporting. The internet adds timely information about the company and its stocks and links to information specifically intended for investors. Firms use links to stock data, presents the advantages to hold stock’s company, include the list of analysts or links to analysts who follow the firm. Moreover, the internet offers many presentation format features that allow investors to be better informed than with traditional communication channels.

MAJ

27,2

136

These features include mailing list subscribers, answers to frequently asked questions, an online investor information order service and audio or video files to get more comprehensive information. The internet could then be used for the provision of specific information for investors that is not available through other sources.

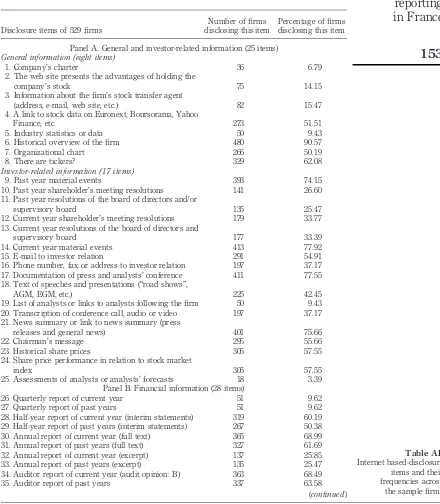

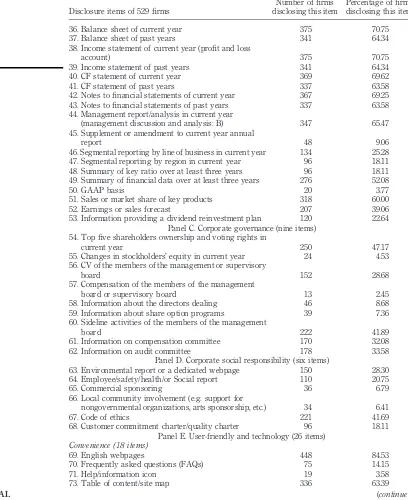

Data items’ frequency

The checklist of disclosed items and their frequency across sample firms are provided in the Appendix. Panel A includes information provided to current and potential investors to better know the company. The most commonly disclosed items among investor-related information are the current year material events (77.92 percent) followed by documentation of press and analyst’s conferences (77.25 percent) and news summary (75.66 percent). These items are provided more frequently than annual reports because they can be easily adjusted on the web sites without any cost. As for financial reporting items, Panel B shows that complete current year annual reports are found in merely 69 percent of the web sites while only 25.85 percent of the web sites contain excerpts from these reports. Non-mandatory releases such as quarterly reports are provided in only 9.62 percent of the cases. Current year balance sheet and income statements are more frequently available on firms’ web sites than any other accounting item (70.75 percent of the cases for both items). Corporate governance and corporate and social responsibility items are, however, less currently available (Panels C and D). We notice that only 28.3 percent of the sample firms provide a report or a dedicated webpage for environmental issues.

The remaining items are for presentation format of web sites. With respect to convenience items, almost 85 percent of sample firms have English web pages to facilitate access to information for foreign investors. Many French firms use various features to allow an easy navigation on their web sites: 63 percent of firms provide a site map, 48 percent allow investors to subscribe to a mailing list and 65 percent allow an easy access to investor relation section (measured by the number of clicks to get into investor relation). Even though FAQs offer the opportunity for firms to lessen the number of e-mails from investors, this item is only provided by 14.15 percent of the sample firms. With respect to technology items, a substantial proportion of French companies use PDF or HTML format (70.75 percent) and graphic images (68.87 percent) to present their financial information whereas video files are only available at 11.13 percent of the cases. It is rather surprising that few companies in the sample provide video files which allow users to better analyze information than traditional paper-based reporting. No company of the sample firms presents financial data in the XBRL format that enables investors to automatically extract and download any specified financial figure. As for timeliness, Panel F indicates that French firms provide timely information regarding press releases (73 percent) and share prices (59.81 percent). It shows also that nearly 48 percent of sample firms use newsletters or e-mail alerts and 57 percent of them provide a calendar of future events. However, less than 1 percent of the sample firms produce information on monthly or weekly sales and operating data. Although internet offers the opportunity to update reported information without delay, most of French firms disseminate quickly traditional accounting documents rather than new accounting information such as monthly or weekly operating data. This can be due to the competitive consequences that firms support while disclosing recent information.

Corporate

reporting

in France

137

Variable measurement

We use six disclosure indexes to measure the extent of web-based corporate reporting. TScore is the total score including all the 101 collected items. Following Debrecenyet al.

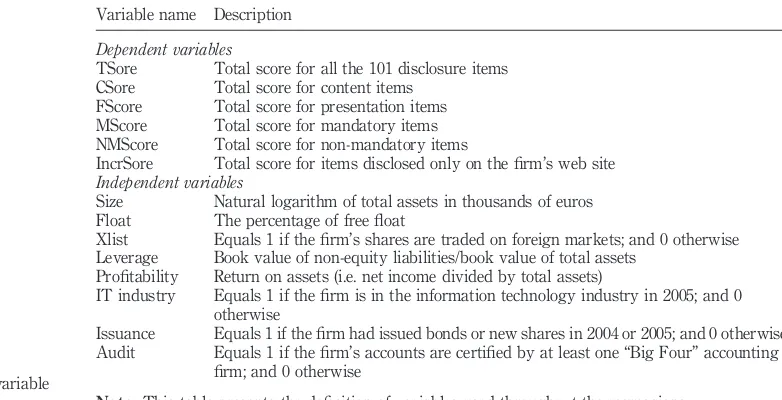

(2002), this score is divided into a content score (CScore) and a format score (FScore). We form also a mandatory score (Mscore) and a non-mandatory score (NMScore). Incremental score (IScore) is used to highlight the use of internet as a complementary medium to traditional reporting. The explanatory variables include firm characteristics. Size is measured as the natural logarithm of total assets. Float is a measure of ownership dispersion calculated as the proportion of company’s free float share. Xlist indicates whether a firm cross-lists or not. Leverage is the book value of non-equity liabilities divided by the book value of total assets. Profitability is measured by the return on assets ratio. Issuance is a dummy variable that equals 1 if the firm has issued new shares or bonds in 2004-2005 and 0 otherwise. We use a dichotomous variable to control for IT industry. These definitions are provided in Table III.

Analysis and discussion Descriptive statistics

Table IV provides descriptive statistics for internet disclosure scores and presents sample characteristics. Panel A presents the statistics of continuous variables. The total web-based corporate reporting score (TScore) ranged from 0 to 84 with an average of about 39. This indicates that scores differ greatly across French firms. We also notice that financial information is provided on the web sites of merely four fifth of the sample companies which is higher than the proportion reported by Xiaoet al.(2004) on the Chinese market (71 percent). Similarly, Ashbaughet al.(1999) found that 70 percent of US firms disclose financial information on their web site during 1998. This result

Variable name Description

Dependent variables

TSore Total score for all the 101 disclosure items CSore Total score for content items

FScore Total score for presentation items MScore Total score for mandatory items NMScore Total score for non-mandatory items

IncrSore Total score for items disclosed only on the firm’s web site

Independent variables

Size Natural logarithm of total assets in thousands of euros Float The percentage of free float

Xlist Equals 1 if the firm’s shares are traded on foreign markets; and 0 otherwise Leverage Book value of non-equity liabilities/book value of total assets

Profitability Return on assets (i.e. net income divided by total assets)

IT industry Equals 1 if the firm is in the information technology industry in 2005; and 0 otherwise

Issuance Equals 1 if the firm had issued bonds or new shares in 2004 or 2005; and 0 otherwise Audit Equals 1 if the firm’s accounts are certified by at least one “Big Four” accounting

firm; and 0 otherwise

Note:This table presents the definition of variables used throughout the regressions Table III.

Summary of variable definitions

MAJ

27,2

138

reflects the widespread use of the internet to communicate with investors. It also shows that in France the internet is not used for marketing and commercial purposes only. The extent of information disclosed on the web varies across companies but a large proportion of these companies use the internet to disseminate financial information.

We notice that the mean (median) score of content is 30 (27). It equals 12 (13) for the presentation format. The averaged incremental score equals 6 with a highest score of 15. This shows that the proportion of additional information provided only through internet is relatively weak and that most of information disclosed on the web has already appeared in printed-paper forms. Panel B of Table IV shows that 93.12 percent of sample firms have a web site, 5.29 percent cross-lists and 24.57 percent have issued bonds or new shares in 2004-2005.

Panel A Min. 1st quartile Median Mean 3rd quartile Max. SD

TScore 0 18 43 39.367 57 84 22.168

CScore 0 10 30 27.006 40 60 17.035

FScore 0 8 13 12.391 17 27 5.564

MScore 0 0 15 11.732 18 31 8.121

NMScore 0 7 15 15.274 23 37 9.768

IncrScore 0 0 4 3.9982 7 12 3.5319

Size 0.604 3.667 4.826 5.248 6.638 11.725 2.326

Float 0.130 20.460 34.290 37.057 50.00 94.000 22.279

Leverage 0 0.026 0.103 0.138 0.199 0.986 0.148

Profitability 20.664 0.020 0.048 0.037 0.079 0.365 0.105

Panel B Number Percentage of sample

Xlist 28 5.2930

IT industry 134 25.3308 Issuance 130 24.5747

Audit 169 31.9471

Gen inf 503 95.0851

Fin inf 422 79.7732

CGov inf 304 57.4669

CSR inf 295 55.7656

Content inf 505 95.4631

Notes:Panel A displays descriptive statistics of continuous variables used in the current study; TScore is the total score for all the 101 disclosure items; CSore, FScore, MScore and NMscore are total score for content items, total score for presentation items, total score for mandatory items and total score for non-mandatory items, respectively; IncrScore is the total score for items disclosed only under internet financial reporting; size is computed as the natural logarithm of total assets in thousands of euros; float is the percentage of free float; leverage is the book value of non-equity liabilities over the book value of total assets; profitability is proxied by return on assets (i.e. net income divided by total assets); panel B reports additional statistics on categorical variables; Xlist is a dummy variable that equals 1 if the firm’s shares are traded on foreign financial markets and 0 otherwise; IT industry equals 1 if the firm is in the information technology industry in 2005, and 0 otherwise; issuance equals 1 if the firm had issued bonds or new shares in 2004 or 2005, and 0 otherwise; audit is a dummy variable that equals 1 if at least one of the firm auditors is from a Big Four, and 0 otherwise; Gen inf (Fin inf) is a dummy variable that equals 1 if the firm has at list one general information item (financial information item), and 0 otherwise; CGov inf (CSR inf) is a dummy variable that equals 1 if the firm has at list one corporate governance information item (corporate social responsibility item), and 0 otherwise; content inf is a dummy variable that equals 1 if the firm has at list one content information item, and 0 otherwise

Table IV. Descriptive statistics

Corporate

reporting

in France

139

Univariate analysis

Pearson and Spearman correlations between variables used in the analysis are provided in Table V. According to Gujarati (2004), a serious problem of multicolinearity exists when correlations between the independent variables exceed 0.80 which is not the case in the present study. The VIF values were computed to check the existence of this problem. They range between 1.13 and 2.03 by far below the critical value of ten (Neteret al., 1989). The correlations between the independent variables do not seem then to be at the origin of the multicollinearity problem.

Table VI reports mean and median comparison tests of various disclosure scores between two groups of firms separated each time according to firm characteristics. These characteristics are partitioned based on whether they are above- or below- mean and median levels for the sample. We notice that virtually all the considered firm characteristics are different among the two groups of firms for all categories of disclosure indexes. The univariate tests show that firms with high disclosure levels are more likely to be larger firms, to have low ownership concentration, to be listed on a foreign market in addition to the French market, to be highly leveraged, more profitable and to have issued new shares or bonds in the last two years. These results are obtained for all scores and support our hypotheses.

It is not surprising that profitability is not statistically different depending on the disclosure level of mandatory information since mandatory releases are displayed on a paper-based medium regardless of the level of firm performance.

Multivariate analysis

Regression analyses were run using ordinary least squares estimates and are displayed in Table VII. These models use six scores for web-based disclosures (total, content, format, mandatory, non-mandatory and incremental score). The last model presents the results of the logit regression where the dependent variable is a dichotomous variable indicating whether a firm has a web site. All independent variables are included in the models. The regression analysis shows that all significant variables have the expected signs, providing some support for the results already obtained in the univariate tests.

An important result of the multivariate analysis is that the model using the non-mandatory score as a dependent variable has greater explanatory power (0.55) relatively to the models using total, content, format, mandatory and incremental scores. The lowest explanatory power is given by the mandatory score (0.37). Our findings show that firm characteristics are rather associated with the extent of voluntary items disclosed at corporate web sites and to a lesser extent to mandatory information and to the way the information is presented on the web. This suggests that web sites are more suited for non-mandatory information. If companies just provide annual and interim reports (including the balance sheet, income statement, notes and cash flow statement), then these provided information are not particularly designed for investors. The disclosure of voluntary items through the web such as press releases, analyst’s conference videos, financial calendar and share prices are more likely to meet investors’ specific needs in terms of content and structure. We also notice that the presentation of information to investors on web sites is more strongly associated with the explanatory variables than the content of disclosures on the web. This suggests that web sites are particularly suited for presenting information to investors because they include

MAJ

27,2

140

TScore CScore FScore MScore NMScore IncrScore Size Float Xlist Leverage Profitability IT industry Issuance Audit

TScore 1.000 0.9920* 0.9256* 0.9181* 0.9680* 0.9156* 0.5657* 0.4861* 0.3177* 0.2134* 0.0870* * 0.1961* 0.3382* 0.2055* CScore 0.9929* 1.000 0.8791* 0.9337* 0.9683* 0.8960* 0.5559* 0.4820* 0.3030* 0.2155* 0.0816* * * 0.2015* 0.3378* 0.2058* FScore 0.9345* 0.8880* 1.000 0.7852* 0.8837* 0.8986* 0.5339* 0.4433* 0.3276* 0.1994* 0.0992* * 0.1553* 0.3131* 0.1845* MScore 0.9260* 0.9424* 0.7961* 1.000 0.8325* 0.8167* 0.4566* 0.4797* 0.2661* 0.1979* 0.0788* * * 0.1987* 0.3556* 0.1701* NMScore 0.9618* 0.9605* 0.8868* 0.8121* 1.000 0.8947* 0.5871* 0.4674* 0.3105* 0.2150* 0.0895* * 0.1807* 0.3114* 0.2132* IncrScore 0.8994* 0.8828* 0.8736* 0.7785* 0.8924* 1.000 0.5160* 0.4472* 0.3136* 0.2077* 0.0710 0.2244* 0.3041* 0.1615* Size 0.5716* 0.5672* 0.5410* 0.4435* 0.6205* 0.5551* 1.000 0.3704* 0.3292* 0.3505* 0.0710

20.1731* 0.2145* 0.3633* Float 0.4977* 0.4978* 0.4622* 0.4553* 0.4896* 0.4589* 0.4577* 1.000 0.2927* 0.1461*

20.0240 0.1578* 0.4003* 0.2697* Xlist 0.3209* 0.3045* 0.3448* 0.2326* 0.3377* 0.3365* 0.4445* 0.3274* 1.000 0.0993* *20.0276 20.0212 0.2573* 0.2364* Leverage 0.1053* *0.1078* *0.0861* *0.0843* * *0.1179* 0.0994* * 0.1816* 0.1169* 0.0380 1.000

20.1998* 20.3409* 0.2639* 0.0883* * Profitability 0.0924* *0.0915* *0.0899* *0.0744* * *0.0978* *0.0747* * * 0.1478*20.0422 20.0888* *20.1841* 1.000 0.0850* * *20.0493 0.0136 IT industry 0.2004* 0.2072* 0.1607* 0.2196* 0.1787* 0.2172*

20.1632* 0.1408*20.0212 20.2206* 0.0381 1.000 0.0916* *20.0075 Issuance 0.3502* 0.3471* 0.3295* 0.3447* 0.3187* 0.3093* 0.2589* 0.4378* 0.2573* 0.1959*

20.0898* * 0.0916* * 1.000 0.1174* Audit 0.1983* 0.1987* 0.1895* 0.1476* 0.2238* 0.1659* 0.3880* 0.2771* 0.2364* 0.0930* 20.0055 20.0075 0.1174* 1.000 Notes:Statistical significance levels at:*1, * *5 and * * *10 percent (two-tailed), respectively; this table provides the value of the pairwise correlation

between each of the variables used in subsequent analysis; Spearman (Pearson) correlations are above (below) the diagonal; TScore is the total score for all the 101 disclosure items; CSore, FScore, MScore and NMscore are total score for content items, total score for presentation items, total score for mandatory items and total score for non-mandatory items, respectively; IncrScore is the total score for items disclosed only under internet financial reporting; size is computed as the natural logarithm of total assets in thousands of euros; float is the percentage of free float; Xlist equals 1 if the firm’s shares are traded on foreign markets, and 0 otherwise; leverage is the book value of non-equity liabilities over the book value of total assets; profitability is proxied by return on assets (i.e. net income divided by total assets); IT industry equals 1 if the firm is in the information technology industry in 2005, and 0 otherwise; issuance equals 1 if the firm had issued bonds or new shares in 2004 or 2005, and 0 otherwise; audit is a dummy variable that equals 1 if at least one of the firm auditors is from a Big Four, and 0 otherwise

Table

V.

Pairwise

correlations

among

variables

Corporate

reporting

in

France

141

Firm characteristics

Below median

Above median

p-value of difference

Below median

Above median

p-value of difference

Below median

Above median

p-value of difference

Total score Content score Format score

Size Mean 29.5902 49.2548 (0.0000)* 19.5489 34.5475 (0.0000)* 10.0414 14.7681 (0.0000)*

Median 31 54 (0.0000)* 21 38 (0.0000)* 10 15 (0.0000)*

Float Mean 30.3674 48.3321 (0.0000)* 20.1742 33.8113 (0.0000)* 10.1932 14.5811 (0.0000)*

Median 30 51 (0.0000)* 20 36 (0.0000)* 10 15 (0.0000)* Xlist Mean 37.6866 69.4286 (0.0000)* 25.7804 48.9286 (0.0000)* 11.9381 20.5 (0.0000)* Median 41 69.5 (0.0000)* 29 51 (0.0000)* 13 20 (0.0000)*

Leverage Mean 34.47148 44.2068 (0.0000)* 23.3384 30.6316 (0.0000)* 11.1939 13.5752 (0.0000)*

Median 38 50 (0.0000)* 26 35 (0.0000)* 12 14 (0.0000)*

Profitability Mean 36.8113 41.9318 (0.0078)* 25.2830 28.7349 (0.0197)* * 11.5283 13.2576 (0.0003)* Median 41 44 (0.0223)* * 30 30 (0.0405)* * 13 13.5 (0.0026)* IT industry Mean 36.7823 46.9851 (0.0000)* 24.9519 33.0597 (0.0000)* 11.8709 13.9254 (0.0002)*

Median 39 51 (0.0042)* 26 35 (0.0045)* 13 14 (0.0039)*

Issuance Mean 34.9399 52.9539 (0.0000)* 23.6341 37.3539 (0.0000)* 11.3459 15.6 (0.0000)*

Median 38 53 (0.0000)* 25 37 (0.0000)* 12 15 (0.0000)* Audit Mean 36.3583 45.7752 (0.0000)* 24.6889 31.9408 (0.0000)* 11.6694 13.9289 (0.0000)* Median 40 50 (0.0000)* 27.5 36 (0.0000)* 13 15 (0.0000)*

Mandatory score Non-mandatory score Incremental score

Size Mean 9.0451 14.4487 (0.0000)* 10.5038 20.0989 (0.0000)* 2.7895 5.7719 (0.0000)*

Median 11 16 (0.0000)* 11 22 (0.0000)* 2 6 (0.0000)*

Float Mean 14.7396 8.7121 (0.0000)* 11.4621 19.0717 (0.0000)* 2.9773 5.5623 (0.0000)* Median 16 9.5 (0.0000)* 11 20 (0.0000)* 2 6 (0.0000)*

(continued)

Table

VI.

Univariate

tests

MAJ

27,2

142

Firm characteristics

Below median

Above median

p-value of difference

Below median

Above median

p-value of difference

Below median

Above median

p-value of difference

Xlist Mean 11.2854 19.7143 (0.0000)* 14.4950 29.2143 (0.0000)* 3.9960 9.2143 (0.0000)*

Median 15 20.5 (0.0000)* 15 29 (0.0000)* 4 9 (0.0000)* Leverage Mean 10.21293 13.2331 (0.0000)* 13.1255 17.3985 (0.0000)* 3.5589 4.9774 (0.0000)* Median 14 16 (0.0000)* 13 18 (0.0000)* 3 5 (0.0000)*

Profitability Mean 11.1547 12.3106 (0.1017) 14.1283 16.42424 (0.0068)* 3.8329 5.5672 (0.0273)* *

Median 14 15 (0.1315) 16 15 (0.0127)* * 4 4 (0.0205)* *

IT industry Mean 10.6937 14.7910 (0.0000)* 14.2582 18.2687 (0.0000)* 5.2911 7.0746 (0.0000)* Median 14 16 (0.0056)* 13 19 (0.0058)* 3 6 (0.0000)* Issuance Mean 10.1353 16.6308 (0.0000)* 13.4988 20.7231 (0.0000)* 3.6591 6.1538 (0.0000)*

Median 13 17 (0.0000)* 13 20 (0.0000)* 3 6 (0.0000)*

Audit Mean 10.9111 13.4793 (0.0007)* 13.7778 18.4615 (0.0000)* 5.2944 6.6982 (0.0001)*

Median 14 16 (0.0001)* 14 20 (0.0000)* 5 7 (0.0002)*

Notes:Significance levels at:*1,* *5 and * * *10 percent, respectively; this table reports mean and median comparison tests of various scores between two groups of firms separated each time according to firm characteristic; these characteristics are partitioned based on whether they are above- or below-median levels for the sample; two-tailedt-statistics from a parametric test (Mann-Whitney rank sum tests) are used for the pairwise comparison of means (medians); TScore is the total score for all the 101 disclosure items; CSore, FScore, MScore and NMscore are total score for content items, total score for presentation items, total score for mandatory items and total score for non-mandatory items, respectively; IncrScore is the total score for items disclosed only under internet financial reporting; size is computed as the natural logarithm of total assets in thousands of euros; float is the percentage of free float; Xlist equals 1 if the firm’s shares are traded on foreign markets, and 0 otherwise; leverage is the book value of non-equity liabilities over the book value of total assets; profitability is proxied by return on assets (i.e. net income divided by total assets); IT industry equals 1 if the firm is in the information technology industry in 2005, and 0 otherwise; issuance equals 1 if the firm had issued bonds or new shares in 2004 or 2005, and 0 otherwise; audit is a dummy variable that equals 1 if at least one of the firm auditors is from a Big Four, and 0 otherwise; thep-value of thet-test and medians tests of equality is reported in parentheses

Table

VI.

Corporate

reporting

in

France

143

OLS regressions Logit regressions Panel A VIF TScore CScore FScore MScore NMScore FinScore IncrScore Panel B Web site

Size 2.0328 4.1804 3.1524 1.0112 1.0562 2.0962 1.2574 0.7700 Size 0.0874 (10.5858)* (10.3145)* (9.5814)* (6.7326)* (12.1143)* (7.4938)* (10.1801)* (0.8362)

Float 1.7257 0.1363 0.1119 0.0273 0.0616 0.0503 0.0536 0.0170 Float 0.0186 (3.4883)* (3.7129)* (2.6662)* (3.8549)* (3.0594)* (3.1803)* (2.2493)* * (1.1226)

Cross-listing 1.4001 7.7718 5.1001 2.5950 1.3028 3.7972 0.2726 0.6529 Cross-listing – (2.5266)* * (2.1116)* * (3.2899)* (1.2499) (2.5511)* * (0.2275) (0.9297) –

Leverage 1.2273 4.3958 3.3328 0.8118 0.9197 2.4131 0.5402 0.7962 Leverage 4.4570 (1.0138) (1.0120) (0.6736) (0.5165) (1.3904) (0.2794) (0. 9390) (2.2804)* *

Profitability 1.1328 0.09883 0.0774 0.0226 0.0385 0.0389 0.0496 0.0047 Profitability 0.0347 (1.5958) (1.5756) (1.4703) (1.3511) (1.6366) (1.6692)* * * (0.4090) (2.4936)* *

IT industry 1.9370 6.6654 5.1997 1.4170 2.4073 2.7924 2.4264 1.3031 IT industry 20.3240 (3.3904)* (3.4593)* (2.6354)* (3.0450)* (3.1866)* (3.0469)* (3.3629)* (

20.7260) Issuance 1.3403 6.3177 4.7706 1.4839 2.9179 1.8527 2.9086 1.1396 Issuance –

(3.9508)* (3.8322)* (3.5246)* (4.5648) * (2.5110) * * (4.1475)* (3.5889)* –

Audit 1.3886 7.0450 5.4665 1.6634 2.3842 3.0823 2.5549 1.1848 Audit 1.1282 (4.3923)* (4.4047)* (3.9448)* (3.05503)* (4.5160) * (3.6810)* (3.7608)* (1.7639)* * *

Industry dummies Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Industry

dummies Yes

Constant 23.6339 25.0997 1.5013 0.0506 25.1503 0.4160 22.2536 Constant 20.4684 (20.8796) (21.6101) (1.2775) (0.0351) (22.5284) * (0.2503) (22.6088)* (20.4324) AdjustedR2 0.5132 0.5108 0.4505 0.3717 0.5506 0.4026 0.4739 Pseudo-R2 0.2071

F-value 102.48* 59.25* 35.23* 38.31* 62.14* 30.25* 45.10* x2 40.94*

Observations 529 529 529 529 529 529 529 Observations 568

Notes:Significance levels at:*1,* *5 and* * *10 percent, respectively; all the regressions in panel A are run using an ordinary least squares specification;

the dependent variable depends on the regression; TScore is the total score for all the 101 disclosure items; CSore, FScore, MScore, NMscore and FinScore are total score for content items, total score for presentation items, total score for mandatory items, total score for non-mandatory items and total score for finance information items, respectively; IncrScore is the total score for items disclosed only under internet financial reporting; size is computed as the natural logarithm of total assets in thousands of euros; float is the percentage of free float; Xlist equals 1 if the firm’s shares are traded on foreign markets, and 0 otherwise; leverage is the book value of non-equity liabilities over the book value of total assets; profitability is proxied by return on assets (i.e. net income divided by total assets); IT industry equals 1 if the firm is in the information technology industry in 2005, and 0 otherwise; issuance equals 1 if the firm had issued bonds or new shares in 2004 or 2005, and 0 otherwise; audit is a dummy variable that equals 1 if at least one of the firm auditors is from a Big Four, and 0 otherwise; industry dummies following Campbell’s (1996) classification are included in all regressions but not reported; panel B presents the logistic regression results of web site adoption; web equals 1 for firms with functioning web sites and 0 for firms with no web sites; Fin inf is a dummy variable that equals 1 if the firm has at list one financial information item, and 0 otherwise; thep-value of thet-test is in parentheses

Table

VII.

Multivariate

analysis

MAJ

27,2

144

technology-specific presentation advantages (Deller et al., 1999). These advantages include ease of access, widespread, facilities for data comparison, analysis and speed. As hypothesized, the extent of web site disclosures is positively related to firm size. All retained scores are significantly associated with firm size at the 1 percent level. Companies that are larger in size are more likely to supplement traditional financial reporting mechanisms with web-based ones in order to benefit from decreasing agency costs ( Jensen and Meckling, 1976). They are likely to face lower costs of disclosure (Ho and Wong, 2001) and lower competitive costs (Fergusonet al., 2002). Moreover, big companies have more expertise to adopt the internet as a medium to disseminate information. This likely explains why firm size is the strongest explanatory variable for web-based disclosures. This result is consistent with the findings of existing studies related to corporate disclosures on web sites by Brennan and Hourigan (2000), Ettredge et al. (2001, 2002), Debreceny et al. (2002), Marston and Polei (2004) and Xiaoet al.(2004). OurH1is then supported. The extent of internet corporate disclosures is positively associated with firm size.

In line with ourH2, the findings show that the float of companies’ shares is positively and significantly associated with internet reporting scores. As share ownership is dispersed, additional disclosures help mitigate the conflicts of interests between managers and shareholders ( Jensen and Meckling, 1976). As the ownership structure of French firms is rather concentrated, large shareholders do not encourage a broader dissemination of information through the internet medium since they have a privileged access to private information. In less concentrated ownership structures, the demand for public information is higher in comparison to controlled structures. Internet financial reporting helps reduce agency costs and information asymmetry between managers and shareholders and between large and small shareholders (Ho and Wong, 2001). This result supports the agency theory hypothesis and is consistent with the findings of Pirchegger and Wagenhofer (1999) in Austria, Oyelereet al.(2003) in New Zealand and Kelton and Yang (2008) in the USA suggesting that shareholders who own small proportions of shares use internet more than other sources. The extent of internet financial reporting also increases with the shareholders’ dispersion.

The results also show that the extent of web-based disclosures is not associated with firm performance measured by the return on assets. Firm performance is only significant with the probability of having a web site. The logit regression shows that profitability is significantly and positively related to the existence of a web site. Firms that disclose information on the web are likely to be more profitable than firms that do not. The use of the internet as a mean to communicate with the market is then driven by competitiveness among firm industries.

While it significantly affects the presentation format and the incremental use of web sites, there is no effect on content, mandatory, non-mandatory and total scores of cross-listing. This result is surprising and do not support ourH4. As indicated in literature, cross-listed firms display more information for their foreign investors given the temporal information asymmetry faced by foreign investors with paper-based disclosures (Oyelere et al., 2003; Debreceny et al., 2002). It can be seen that Xlist is rejected from the logit regressions. All firms with a web site and with at least one financial information item are cross-listed. The commitment to engage in internet corporate disclosures is motivated by the presence of foreign investors because these investors could hardly obtain information through other channels without difficulties.

Corporate

reporting

in France

145

The results show a positive and significant relationship between auditor’s type and the extent of disclosure on the web. This finding corroborates ourH5and is in line with the one found by Xiaoet al.(2004) for Chinese companies. Large audit size plays a role in defining information disclosure strategies and is likely to offer a guarantee against the loss of control of information disclosed on the web by French managers.

Results on leverage are not consistent with the expectation of agency theory. The insignificant relationship between leverage and web-based reporting is in line with the results of Brennan and Hourigan (2000) and Debrecenyet al.(2002). If agency theory is not a good explainer of web-based financial reporting, then the size phenomenon may be related to the costs of information suited for internet and competitive advantages rather than agency costs.

Table VII also shows that firms belonging to IT industry are more likely to use the internet to disseminate their information for a broader scope. According to ourH7, these firms disclose more information than firms from other industries and underline the use of format presentation advantages. This finding is obvious and could be driven by higher internet presentation skills of IT industry relatively to other industries. Firms in IT industry experience low costs to display and present information on web sites. In the UK, however, no significant relationship was found between industry type and extent of financial disclosure on firm homepages (Craven and Marston, 1999). The hypothesized effect of capital issue is strongly supported. All coefficients are significantly positive at the 1 percent level. Firms in need of external capital are likely to expand the scope of their disclosures to benefit from external capital sources. This is consistent with Lang and Lundholm (1993) results but in contrast with Xiaoet al.

(2004) findings on the Chinese market. Internet could be used as an important medium to communicate timely and low cost information for financial purposes.

Robustness tests

In this section, we address several robustness issues by performing a set of sensitivity analyses. Only tests for the Total Score equation are tabulated for sake of brevity.

Extended sample. Consistent with prior research (Xiaoet al., 2004); we repeat the analysis after including the 39 firms with no web site to our sample. We assign a score of 0 to each of these firms. The regression results show that the positive influence of leverage and profitability are now statistically significant. This