The Food Manufacturing Industry in Zimbabwe

Felix T. Mavondo

MONASHUNIVERSITYThis article investigates the relationship among environment, strategy, and and k-selection. When environmental pressure favors those

organizational characteristics and performance in an industry at various organisms able to reproduce quickly (such as opening new

stages of deregulation in a developing economy. The focus of the study is markets or introducing new products) they called this

r-selec-organizational adaptation under different market conditions. The article tion, while k-selection means that environmental pressure

seeks to establish the contingency perspective of adaptation. The research favors organizations that compete on efficiency of using

exist-findings suggest that once an organization has chosen its strategy, organi- ing resources. On the basis of this, Brittain and Freeman

zational characteristics must be consistent with that strategy irrespective (1980) developed r-strategies and k-strategies that correspond

of the environment in which the organization operates. The results, with to the theoretical framework we used for this article.

respect to organizational variables, indicate that the environment is neither Miles and Snow (1978) developed the typology that is used

a quasi-moderator nor a homologizer. However, with respect to organiza- to organize the ideas in this article. Related work has been done

tional performance, the environment influences the form of the strategy– by McDaniel and Kolari (1987), McKee, Varadarajan, and Pride

performance relationship hence it is a quasi-moderator. The article then (1989), and Conant, Mokwa, and Varadarajan (1990).

discusses the implications of these findings for managers and policy makers The article is organized as follows. We begin with an outline

within the context of a developing economy and for academic research of the Miles and Snow typology, followed by discussion of

in general.J BUSN RES 2000. 50.305–319. 2000 Elsevier Science environmental changes in the food manufacturing industry

Inc. All rights reserved. in Zimbabwe. We develop hypotheses and empirically test them and finally discuss the results and their implications.

Overview of the Miles and

O

rganizational adaptation has been an importantsub-ject of research in strategic management (Ginsberg

Snow (1978) Typology

and Buchholtz, 1990; Hrebiniak and Joyce, 1985;Prospectors

Boeker and Goodstein, 1991; Zajac and Shortell, 1989;

Chak-“A true prospector is almost immune from the pressures of ravarthy, 1982). Adaptation is conceptualized as gradual,

long-a chlong-anging environment since this type of orglong-anislong-ation is term, and incremental change in response to environmental

continually keeping pace with change, and . . . frequently conditions (Tushman and Romanelli, 1985). Adaptation means

creating change itself” (Miles and Snow, 1978, p. 57). The adjustment toward a closer fit between strategy and

environ-primary capability of prospectors is that of finding and ex-ment (Lawrence and Lorch, 1969). While some theorists

(An-ploiting new products and markets opportunities. The pros-drews, 1971; Schendel and Hofer, 1979) have suggested that

pector’s domain is usually broad and in a state of continuous managers change their strategies to reflect environmental

development. The systematic addition of new products and changes, others (Quinn, 1980; Hannan and Freeman, 1984;

markets gives the prospectors’ products and markets an aura Boeker, 1989) observe that organizations are constrained in

of fluidity. The prospector seeks to be “first in” with new the ability to respond. Using an ecological perspective of the

products, however, this extensive adaptive capacity may come adaptive process, MacArthur and Wilson (1967) identified

at a cost (Miles and Snow, 1978; Zammuto, 1982; Frazier, two types of selection pressures which they called r-selection

Spekman, and O’Neal, 1988; McKee et al., 1989). Flexibility may be traded for efficiency. Prospectors can be viewed as

Address correspondence to Felix T. Mavondo, Monash University, Faculty of following r-strategies (Zammuto, 1988) where successful per-Business and Economics, Peninsula Campus, P.O. Box 527, Frankston, Vic

3199, Australia. Tel: (61-3) 99044621; Fax: (61-3) 99044145. formance relates to “first mover” advantages that may include

Journal of Business Research 50, 305–319 (2000)

2000 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN 0148-2963/00/$–see front matter

providing an industry standard. Thus, prospectors place a

Reactors

premium on product and market development. They scan the Organizations categorized as reactors lack consistent strate-environment extensively in order to react timely and possibly, gies. They respond to environmental pressures on an ad hoc take proactive steps to precipitate change in their product basis. They may have inconsistent structures, and are not market. This is what is called “creative destruction” (Baldwin, aggressive in what they do. They react slowly to environmental 1987; Oakely, 1990; Plater and Rahtz, 1989), or “thriving on change and perform poorly as a result (Chakravarthy, 1982; chaos” (Peters, 1987). Hambrick, 1983). This experience of slow response and poor

performance forces them to be even less proactive in future

Defenders

endeavors (Miles and Snow, 1978). Reduced slack or scarcity“While perfectly capable of responding to today’s world, a of resources may induce managerial paralysis causing rigidity defender, is ideally suited for its environment only to the and propelling the organization to decreased performance extent that the world of tomorrow is similar to that of today” (Smart and Vertinsky, 1977). Miles and Snow developed this (Miles and Snow, 1978, p. 47). The most notable features of class as a repository for organizations that did not fit into the defender’s product-market domain is its narrowness and the other three groups, however, other researchers (Conant, stability. Defenders typically direct their products or services Mokwa, and Varadarajan, 1990) identify them as a distinct to a limited number of segments and engage in continuous and stable group.

and intense efforts to become the most efficient operators thus they are conceived as following k-strategies. Success for

defenders depends on aggressively maintaining prominence in

Organizational Strategy and

these segments. With stable markets, management can directEnvironmental Adaptability

attention toward reducing manufacturing and distributionThe Miles and Snow (1978) typology suggests that an organi-cost while simultaneously maintaining or improving quality.

zation’s strategic posture may lead to better performance if it The result is seen in the defender’s ability to be competitive

is closely aligned to the demands of the task environment. on either a price or quality basis (Miles and Snow, 1978, p. 37).

There are two extremes to the adaptability of the organization. However, defenders may be poorly placed to respond when

At one extreme, an organization can maintain an internal focus customers’ needs change (Abernathy and Wayne, 1974;

Hen-by concentrating on efficient operation in a narrowly defined derson, 1984). This arises from some resources such as plant

product market. At the other extreme, an organization can and equipment having little flexibility (Pilling et al., 1994;

Za-maintain an external focus which permits adapting to market heer and Venkatraman, 1995), historical precedents and norms

changes but at potentially significant loss of operating effi-(Aldrich, 1979), career politics, culture (Barney, 1986), and

ciency. The problem of balancing the benefits and costs of adherence to yesterday’s distinctive competencies (Daft,

Sormu-adaptability is fundamental to business strategy (Abernathy nen, and Parks, 1988; Hamel and Prahalad, 1994). Thus

de-and Wayne, 1974; Miles de-and Snow, 1978). Weick (1979) fender organizations deliberately reduce both adaptive

capa-summarized the trade-off between an internal and external bility and the costs associated with such adaptability.

focus by noting that “adaptation precludes adaptability” (p. 135). The implication is that organizations fitted to a specific

Analyzers

environment may have difficulty in adapting to change, The analyzer’s domain is a mixture of stable and changing

whereas organizations designed for change may not fit any product/markets (Nicholson, Rees, and Brooks-Rooney, 1991).

particular environment. The managerial challenge is to design The ideal analyzer is always ready to move quickly into new

organizations that are both adaptable and efficient. products or markets that recently gained some degree of

accep-Operating efficiency is associated with a narrow scope of tance. Much of the growth of the analyzer occurs through

activities and a strong emphasis on standard procedures. Adap-market penetration as the organization’s basic strength comes

tive capability, on the other hand, has been associated with the from its traditional product-market base and moderate

techno-“wandering organization” (Zammuto, 1988) or involvement of logical efficiency (Miles and Snow, 1978, pp. 72–74). In many

the “non-right type” individual (Cameron and Whetten, 1983, respects analyzer organizations are a hybrid between

prospec-p. 257) to arrive at variations of standard practice. From these tors and defenders. They seek to be “second” in new markets

observations we note that adaptive organizations have been or products through a process of imitation. To succeed, they

characterized as deliberately inefficient. From an ecological must enter new products or markets more cost-efficiently

perspective, we define prospectors as r-generalists, defenders than prospectors. Operating in a stable environment enables

as k-specialists, and analyzers as k-generalists. We note that relatively high levels of efficiency (operating like a defender),

generalism and specialism coexist and are fundamentally inter-while in more fluid environments their success is associated

related (Carroll, 1985). The success of generalism (prospec-with entrepreneurship and depends on speed and efficiency.

tors) creates the conditions favorable for specialism. General-This is similar to Bhide’s (1986) “hustle as strategy” or the

and special needs unattended. Thus prospectors will open distinctly different characteristics and that this distinctiveness is maintained in different environments” (McKee, Varadarajan, new markets, as these show promise they become attractive

to analyzers who enter more cost-effectively and build large and Pride, 1989, p. 23).

Congruence between organizational strategy and organiza-market share. The efficiency of defenders allows them to take

market share from analyzers as the industry output becomes tional variables can be examined by comparing means of orga-nizational variables across the strategy types. In this article commoditized hence industry dynamics are generated through

innovation, mass production, and commoditization. the Miles and Snow typology is the theoretical anchor for ordinally arraying the strategy types according to level of The Miles and Snow (1978) typology captures the

business-level strategic trade-off between external and internal orienta- adaptability (McKee et al., 1989; Jennings and Seaman, 1994; Oktemgil and Greenley, 1997).

tion. In the Miles and Snow (1978) typology the organizations

that most actively seek new markets and products (the pros- The organizational variables investigated in this article are: market orientation, operating efficiency, planning capability, pectors) are hypothesized to have the greatest adaptive

capa-bility. Strategy types can be ordered by degree of increasing management style, technological innovation, and human re-sources management. For each of these variables three hypoth-adaptability as: reactor-defender-analyzer-prospector (McKee

et al., 1989). eses are developed. The first two are related to microcon-gruency, the third is related to macrocongruency.

This article is based on an investigation of the food pro-cessing sector in Zimbabwe (Mavondo, 1993). At the time of

Market Orientation

the study (1992/1993), the food sector was in the process of

deregulation, some firms were operating under a regulatory A market orientation is considered an organizational adapta-regime, others in an open market, while the third category tion to consumer needs and tastes (Narver and Slater, 1990; was in transition following deregulation which had started in Ruekert, 1992; McKee et al., 1989; Walker and Ruekert, 1987; 1987. These three regulatory regimes represent the environ- Walker, Boyd, and Larreche, 1992). Collis (1991) argues that ment under investigation. The research tests the hypotheses adaptive capability is the ability to identify and respond that: (1) the level of adaptive effort is systematically related quickly to change before it happens or once change has hap-to strategy type; (2) there are significant differences in the pened. Bourgeois and Eisenhardt (1988) and Powell (1992) characteristics of the strategy types; (3) for each strategy type demonstrate empirically the link between adaptive capability there are no significant differences in the characteristics across and organizational success. The level of market orientation the environments; and (4) the performance of a given strategy should be highest in the prospector organizations (Miles and type is contingent upon the match between the adaptive con- Snow, 1978; McDaniel and Kolari, 1987; Conant, Mokwa, tent of the strategy and the environment. and Varadarajan, 1990). Hence:

H1a: The level of market orientation is positively related to the level of adaptive capability inherent in the

Hypothesized Relationships

organizational strategy.

Strategy Type/Organizational

H1b: There are significant differences in the mean level of

Variables Congruence

market orientation among the strategy types.Contingency theory postulates that the effectiveness of an

orga-H1c: The strategy type–market orientation relationship is nization depends on the congruence between the elements of the

maintained in all environments. organizational sub-system and the demands of the environment

(macrocongruence), as well as the congruence of these sub-

Operating Efficiency

system elements among each other (microcongruence). TheThe distinctive competence of the defenders is in controlling contingency approach that has gained general acceptance is

costs through routinization of operations, investing in efficient that the environment operates as a homologizer, that is,

envi-manufacturing technology, and focusing on a narrow range ronments influence the strength of the relationship between

of activities (Miles and Snow, 1978; Hambrick, 1980; Snow strategy and organizational variables but not the form (there is

and Hrebiniak, 1980). Lowering average and marginal costs no significant interaction between strategy and environment)

enables a firm to reduce prices or increase profits or both, (Prescott, 1986; McKee et al., 1989; Schroder and Mavondo,

and allows more options in competitive decision making. 1994; Venkatraman, 1989).

Cost-cutting innovations are particularly attractive because Development of a contingency perspective or

organiza-their effects are more predictable, the firm has more control tional variables requires the demonstration of (1) congruence

over costs than it does over other aspects of production and between strategy type and organizational variables

(microcon-marketing, and cost-cutting innovation is less likely to be gruency), and (2) maintenance of this relationship in different

detected and imitated immediately by competitors. Hence: environmental states (macrocongruency) (Fry and Smith,

1987). “This [establishing a contingency perspective] means H2a: The level of operating efficiency is negatively related to the level of adaptive capability.

H2b: There are significant differences in the mean level of (1991) and Jaworski (1988), the more uncertain the problem or opportunity the more desirable it is to have higher fre-operating efficiency across the strategy types.

quency and informality in communication patterns. Prospec-H2c: The strategy type–operating efficiency relationship is

tor organizations need to have more organic management maintained in all environments.

styles than other strategy types because they tend to operate in fast changing environments or seek to proactively change

Planning System’s Capability

their environment. It is hypothesized that prospectors will be A firm’s ability to adapt to changing markets depends on the most organic and the defenders the most mechanistic. market scanning (McKee et al., 1989; Walker and Ruekert, Hence:

1987; Lant, Milliken, and Batra, 1992). Environmental

scan-H4a: Organic managerial style is positively related to the ning is the domain of strategy types with an external

orienta-level of adaptive capability inherent in the organiza-tion (Snow and Hrebiniak, 1980; Hambrick, 1983; McDaniel

tion strategy. and Kolari, 1987). Strategic planning is the search for more

effective and efficient routines, the genes that determine how H4b: There are significant differences in managerial style the firm evolves. The creative planner takes present routines across the strategy types.

and production rules and by “gene splicing” creates new rou- H4c: The strategy type-managerial style relationship is tines, tactics, and functions. Firms which are open-minded maintained in all environments.

and good at such creative gene splicing are more competitive

(Nelson and Winter, 1982). Thus, prospectors and analyzers

Innovation

are expected to score better than defenders and reactors.How-Innovation is reflected in new products, manufacturing pro-ever because the strength of analyzers lies in imitation (wait

cesses, and management techniques. A search of the literature and see) and then entering the market with a more

cost-reveals that there are three organizational activities that charac-effective product, they are presumed to require less

environ-terize adaptability: response to product-market opportunities, mental scanning (planning capability) than prospectors whose

marketing activities for responding to these activities, and success depends on first-mover advantages. It is hypothesized

speed of response in pursuing these opportunities (Oktemgil that planning capability will be highest in prospectors,

fol-and Greenley, 1997). All these activities are closely associated lowed by analyzers, then the defenders, with the reactors

with innovation. We expect, in line with the Miles and Snow having the lowest score. Hence: typology, prospectors would have a higher proclivity toward

product innovation (new products) while defenders would H3a: Planning capability is positively related to the level

focus on process innovation (efficiency yielding). The notion of adaptive capability inherent in the organization

of innovation operationalized in this research emphasizes the strategy.

critical role of product innovation in organizational adaptive H3b: There are significant differences in planning

capabil-capability. By this measure, prospectors should score best, ity across the strategy types.

then the analyzers, followed by the defenders and finally the H3c: The strategy type-planning capability relationship is reactors. Hence:

maintained in all environments.

H5a: The level of innovativeness is positively related to adaptive capability inherent in the organization

Management Style

strategy. Burns and Stalker (1961) were the first to suggest that high

H5b: There are significant differences in the mean level of performing firms that compete in complex and dynamic

envi-innovation among the strategy types. ronments adapt an “organic” form (i.e., organizational

archi-H5c: The strategy type–innovation relationship is main-tecture that is decentralized with fluid and ambiguous job

tained in all environments. responsibilities and extensive lateral communication).

Wood-man, Sawyer, and Griffin (1993) came to the same conclusion

Human Resources Management

in their empirical study. Dickson (1992) argues that when

learning facilitates behavior change and leads to improved Where the environment is highly constraining (such as government regulation) but the degree of conflict in functional performance (Garvin, 1993; Senge, 1990; Sinkula, 1994). For

effective adaptability, human resource practices must also fa- demands is low, it is possible to postulate the existence of an “ideal type.” Under a regulated environment it would appear cilitate unlearning (Schein, 1990; Hamel and Prahalad, 1994)

especially if previous behavior is in conflict with the new the ideal type is a defender with its emphasis on operating demands of the environment. Dess and Origer (1987) find efficiency. Following deregulation the situation changes to that high performing firms in dynamic and complex markets trade-off (Gresov and Drazin, 1997) configuration where a strive for consensus to ensure effective strategy implementa- careful balance of competing functional demands may be criti-tion. The prospectors would be expected to have supportive cal for organizational success. Configurational equifinality has people management skills to stimulate creativity; defenders been investigated by Meyer, Tsui, and Hinings (1993) and would prefer a degree of bureaucratization that is consistent Ketchen, Thomas, and Snow (1993), Venkatraman (1989), with efficient operation of routine functions. Hence: and Venkatraman and Prescott, (1990). Configurational equi-finality is possible under situations of multiple, conflicting H6a: The level of human resources management is

posi-functions combined with structural latitude (e.g., open market tively related to the level of adaptive capability

inher-conditions in this study). Managers will choose between alter-ent in the organization strategy.

natives based on organizational goals and personal prefer-H6b: There are significant differences in human resources ences. Configurations that fit the chosen functions will be management practices among the strategy types. equifinal relative to each other and will outperform those H6c: The strategy type–human resources practices rela- that do not. This implies that under open market conditions tionship is maintained in all environments. prospectors, analyzers, and defenders would perform equally

successfully but reactors will perform poorly.

Strategy Type and Performance

The choice of performance measures, in this research, tookMiles and Snow (1978) suggested that their three stable strat- into account the sentiments expressed by Venkatraman and egy types would be equifinal, that is, there are no differences Ramanujam (1986) who argue that financial measures reflect in performance among the stable types (prospectors, ana- “fulfillment of the economic goals of the firm” (p. 803) and lyzers, and defenders). However, reactors would be expected operational measures reflect “key operational success factors to perform poorly in relation to the stable types. Bourgeois that might lead to financial performance” (p. 804). A number (1980) hypothesized a curvilinear relationship between adap- of measures were used as each reflect a different dimension tive capability and performance. Snow and Hrebiniak (1980) of organizational effectiveness. Hypothesized relationships showed that prospectors and defenders performed equally among environment, strategy type, and organizational perfor-and at lower levels compared to analyzers. The underlying mance are discussed later.

logic is that reactors and defenders will not adapt to market

REGULATED ENVIRONMENT. In this environment the prices changes, while prospectors will incur higher costs for their

of inputs and output were controlled by the government. The greater adaptive capability (McKee et al., 1989; Zammuto,

quality of products had to meet gazetted specifications. Thus 1988). However, Jennings and Seaman (1994) and Hooley,

product innovation was neither rewarded nor encouraged. Lynch, and Jobber (1992) found that prospectors seem to

The most effective means of competing was to be a low-cost perform better than other strategy types. We hypothesize that

producer. This environment is unlikely to be an appropriate H7: The relationship between organization strategy and domain for prospectors while reactors, following inconsistent performance is curvilinear, with optimal performance strategies would be expected to perform poorly. To the extent in organizations that balance efficiency and adaptive that both defenders and analyzers have core competencies requirements (i.e., analyzers). emphasizing efficiency, they would both be expected to per-form relatively well, however, defenders (following

k-strate-Environment, Strategy Type, and Performance:

gies) could be conceived as the “ideal type” for thisenviron-A Contingency Perspective

ment and would be expected to outperform other strategytypes. Hence: The Miles and Snow typology is especially suitable for

exam-ining equifinality. Equifinality has come to mean that

perfor-H8a: In regulated markets, organizational performance is mance can be achieved through multiple different organizational

negatively related to adaptive capability. Defenders configurations even if the contingencies the organizations face

will outperform other strategy types. are the same (Hrebiniak and Joyce, 1985; Nadler and

Tush-TRANSITIONAL ENVIRONMENT. The term transitional is used man, 1988; Pennings, 1992; Scott, 1981; Tushman and Nadler,

here to describe firms whose principal business activities had 1978; Drazin and Van de Ven, 1985; Gresov and Drazin, 1997;

been deregulated between 1987 and 1992. Following deregu-Doty, Glick, and Huber, 1993). Equifinality implies that

strate-lation, successful strategy types change. Competition becomes gic choice or flexibility is available to organization designers

environment. To succeed under these conditions requires that dix A). The scalar measures were computed as the average score on the items. Performance measures were averages over an organization insulates its core competencies, while

simulta-neously increasing its capacity to respond (or proactively pre- a three-year period (1990/91–1992/93). The scales were de-veloped from existing measures as indicated in Appendix A. cipitate change in) the new environment. This suggests the

need for efficiency and adaptability. This suggests that

ana-lyzers should outperform other strategy types. Hence:

Assigning Companies to Strategy Types

To allocate businesses to the Miles and Snow (1978) strategy H8b: Under transitional conditions, performance should

types, a subset of 7 of the 11 questions developed by Conant, be related to the ability to balance efficiency and

Mokwa, and Varadarajan (1990) was used together with the adaptive requirements. Analyzers should outperform

“paragraph” approach (Snow and Hrebiniak, 1980). For each other strategy types.

of the seven questions there were four alternative answers,

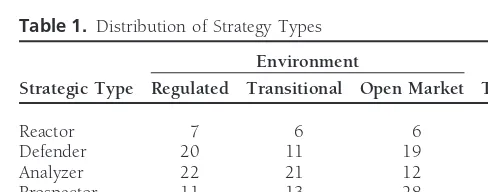

OPEN MARKET (FREE). A number of sub-sectors in the food each corresponding to a specific strategy type. The decision industry in Zimbabwe were never subject to regulation. Com- rule was that a business had to score at least 5 out of 7 panies in these food sectors were classified as operating in an “correct” responses to be classified as one of the four strategy open market environment. The open market environment types (prospector, analyzer, defender, or reactor). If there was permits the conceptualization of equifinality (i.e., multiple any doubt as to the appropriate strategy group, the organiza-configurations that are potentially equally effective). However, tion was classified as a reactor. Once the firm was allocated the conditions in a developing economy like Zimbabwe are to a strategy type, this was compared to how the companies such that demand generally exceeds supply enabling innova- classified themselves on the “paragraph approach.” The two tive producers to charge higher prices and obtain a premium approaches resulted in nearly identical classifications. The on their innovation. The higher margins may adequately off- resulting distribution is shown in Table 1.

set the costs of adaptability and lead to superior performance. To test the proposition that the mean level of marketing effort Hence: increases from reactor to defender to analyzer to prospector strategy types, 15 single items (used to measure market orien-H8c: Under open market conditions organizational

perfor-tation by Narver and Slater, 1990) were compared across the mance is directly and positively related to adaptive

strategy types using a one-way ANOVA. In 14 of these, the capability.

means for prospectors were greater than those for analyzers; analyzers were greater than defenders in 13; defenders were

Sampling and Data Collection

greater than reactors in 14. These results provide a justifica-tion for ordinally ranking the strategy types by adaptive capa-The sample for this study was drawn from a population ofbility. These results are very similar to those of McDaniel and food manufacturing businesses in Zimbabwe. Of the 220 food

Kolari (1987), Conant et al. (1990), Segev (1987), and McKee manufacturing businesses in the principal industrial areas of

et al. (1989). Harare, Bulawayo, Gweru, and Mutare, 25 could not be

reached and 19 refused to participate resulting in an effective

sample size of 176. This is effectively an 80% response rate.

Results

The researcher personally visited the food companies to secureRelationship between Strategy Type and

their participation. This effectively meant most companies

Organizational Variables

were visited at least twice, first to get them to participate,

then to give the questionnaire, and finally to pick up the The results in Table 2 summarize the findings for hypotheses that posit a positive relationship between organizational vari-completed questionnaire. In each participating company the

CEO or his immediate junior was briefed about the aims of ables and organizational strategy. These relationships were tested using Spearman correlation between organization strat-the research and how strat-the questionnaire was to be completed.

The questionnaire was then left for completion with a date egy (ordinally arrayed by adaptive capability) and organiza-(generally 10 days later) fixed for collection by the researcher.

At the time of collecting the completed questionnaire, a general

Table 1. Distribution of Strategy Types

discussion was held to explore any relevant issues not covered

in the questionnaire and any industry insights the respondent Environment

felt important. This was because this study was a part of a Strategic Type Regulated Transitional Open Market Total major study of the food industry in Zimbabwe.

Reactor 7 6 6 19

Defender 20 11 19 50

Development of Scales

Analyzer 22 21 12 55Prospector 11 13 28 52

Appen-Table 2. Organizational Differences by Strategic Type

Mean Value of Organization Strategy Type

Spearman F-Stat

Correlation with Prospector Analyzer Defender Reactor ANOVA Control

Strategy Variables Strategic Type n552 n555 n550 n519 F-Stat for Size Different Setse

Market orientation 0.358a 4.43 3.74 3.58 2.94 7.143a 5.75a P.R, P.D, A.R

Planning capability 0.361a 4.73 4.84 4.26 3.14 8.68a 7.25a A & P & D.R, A.D

Human resource 0.232b 5.00 4.494 4.65 3.96 3.76b 2.99d P.R, P.A

management

Management style 0.245b 4.18 3.88 3.67 3.00 2.43d 2.57d P.R

Innovation 0.377a 4.02 3.74 3.33 3.18 10.25a 9.92a P.D & R, A.D & R

Operating efficiency 20.213c 3.83 4.04 4.43 4.65 2.50d 1.85 R & D.P

ap,0.001.

bp,0.01.

cp,0.05.

dp,0.010.

eAbbreviations: P5Prospector; A5Analyzer; D5Defender; R5Reactor.

tional variables. Support is provided for H1a, H3a, H4a, H5a, size. This is in response to Lindsay and Rue (1980), Robinson and H6a representing respectively, market orientation, plan- (1982), and Hannan and Freeman (1984) who have argued ning capability, management style, innovation, and human that small-sized firms may exhibit different organizational char-resource management. Support for H2a, which posits a nega- acteristics and hence performance. This check was achieved tive relationship between adaptive capability and operating by running an ANOVA model controlling for organizational efficiency, is also provided. These hypotheses were tested size. The results seem to suggest that organizational size has using Spearman’s correlation in recognition of the categorical some effect on human resource management and operating nature of organization strategy. Hypotheses 1b, 2b, 3a, 4b, efficiency. Larger organizations appear to have better human 5b, and 6b that posit the existence of significant differences resource management practices but lower operational effi-among the strategy types for market orientation, operating ciency. However, controlling for organizational size does not efficiency, planning capability, management style, innovation, change the interpretation of the results.

and human resource management, respectively, were sup-ported. These hypotheses were tested using a one-way

AN-Relationship between Strategy Types

OVA. Support for the hypotheses is provided by examining

and Organizational Performance

the F-ratios. All the F-ratios are significant at at least (p ,

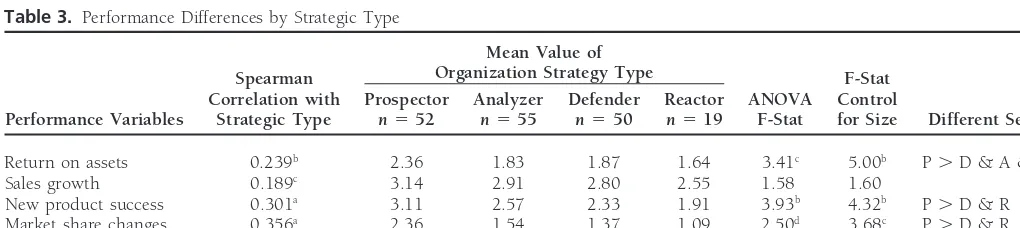

Results in Table 3 relate to performance measures. The results 0.01). Strategy types that are significantly different from each

in Table 3 show that there is a positive relationship between other are indicated. The direction of differences among the

strategy type and each performance measure because all the strategy types across the variables is consistent with literature.

Spearman correlations are significant to at least (p, 0.01).

An additional check on the results was tested, namely, the

extent to which these results are influenced by organizational These results are not consistent with theory because high

adap-Table 3. Performance Differences by Strategic Type

Mean Value of Organization Strategy Type

Spearman F-Stat

Correlation with Prospector Analyzer Defender Reactor ANOVA Control

Performance Variables Strategic Type n552 n555 n550 n519 F-Stat for Size Different Setse

Return on assets 0.239b 2.36 1.83 1.87 1.64 3.41c 5.00b P.D & A & R

Sales growth 0.189c 3.14 2.91 2.80 2.55 1.58 1.60

New product success 0.301a 3.11 2.57 2.33 1.91 3.93b 4.32b P.D & R

Market share changes 0.356a 2.36 1.54 1.37 1.09 2.50d 3.68c P.D & R

Exports 0.284 1.50 1.89 1.40 1.73 3.56b 3.97b A.D

ap,0.001. bp,0.01. cp,0.05. dp,0.010.

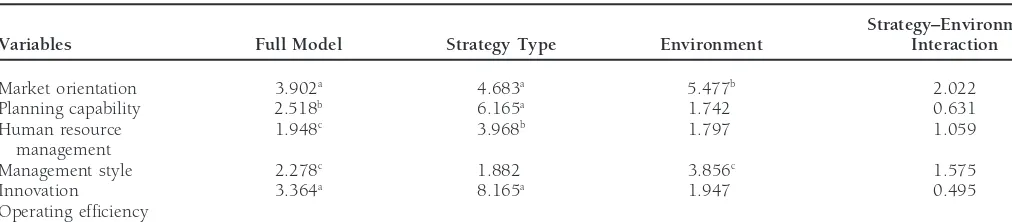

Table 4. ANOVA Model: Environment–Strategic Type Interaction

Strategy–Environment

Variables Full Model Strategy Type Environment Interaction

Market orientation 3.902a 4.683a 5.477b 2.022

Planning capability 2.518b 6.165a 1.742 0.631

Human resource 1.948c 3.968b 1.797 1.059

management

Management style 2.278c 1.882 3.856c 1.575

Innovation 3.364a 8.165a 1.947 0.495

Operating efficiency

Figures in the table are F-ratios.

ap,0.001. bp,0.01. cp,0.05.

tive capability is supposed to impose costs and lead to poorer environment. The F-ratios in the fourth row for each organiza-financial performance (Bourgeois, 1980; Zammuto, 1988; tional variable test the hypothesis that, for a given strategy McKee et al., 1989). The results are, however, consistent with type, there are no significant differences in the means of the Hooley et al. (1992). These results will be analyzed further organizational variable across the environments (i.e., the envi-to gain additional insight (Table 7) later in this article. Com- ronment is not a homologizer).

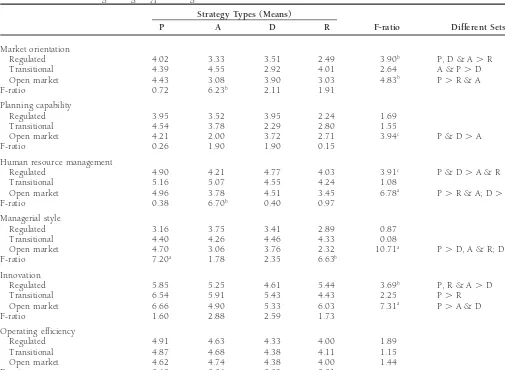

paring the performance differences across the strategy types Results in Table 5 provide further support to the hypothesis indicates there are significant differences as revealed by the that organizations following the same strategy do not have F-ratios. Controlling for organization size does not alter the significant differences in their organizational variables. The level interpretation of the results. Hypothesis 7, which states that of each organizational variable across the environments was analyzers would have the highest performance, is generally tested for significance of difference using a one-way ANOVA. not supported except for contribution of exports to total sales. The F-ratios (in the fourth row for each variable in Table 5) are used as the test statistic. There are 24 F-ratios from comparing

Environment, Strategy, and

organizational variables across environments, 20 of these re-sults are not significant. This supports the hypothesis that theOrganizational Variables

environment in which a specific strategy type operates does To test whether there is congruence in the relationship

be-not influence the level of the organizational variables. How-tween strategy type and organizational variables, it is necessary

ever, four F-ratios were significant indicating that for some to find whether and how the environment affects the

relation-variables the level is significantly influenced by the environ-ship (Fry and Smith, 1987). If the environment influences the

ment. For analyzers, the F-ratios for market orientation and strategy type–organization variable relationship, this would

human resource practices are significant. This arises from be indicated by the significance of the environment–strategy

high mean values in the transitional environment. This could interaction (Sharma, Durand, and Gur-Arie, 1981; Prescott,

potentially arise from over-reacting to environmental change 1986; Venkatraman, 1989). Thus, the significance of the

inter-resulting in temporary misalignment which could be corrected action term (environment3strategy) indicates the

environ-in the short term. For reactors, the significant F-ratio is for ment influences the form of the strategy type–organizational

managerial style where the highest mean occurs in the transi-variable relationship. The organizational transi-variables were treated

tional environment suggesting that following deregulation re-as dependent variables with environment and strategy re-as factors

actor organizations perceived change in managerial style a (independent variables). The results of the ANOVA, presented

potential source of competitive advantage. For prospectors, in Table 4, show that there are no significant interactions

be-the F-ratio for managerial style is significant with highest mean tween strategy and environment. The general conclusion is that

value in the open environment. This is consistent with the the environment moderates the relationship between strategy

need to attract and retain highly innovative people who resent and organizational variables, that is, the environment is a

homol-close supervision and mechanistic managerial styles (Porter, ogizer (Sharma et al., 1981; Prescott, 1986). This means the

1980). Taking the overall results in Table 5 it can be concluded environment may moderate the strategy type–organizational

that there is support for H1c, H2c, H3c, H4c, H5c, and H6c. variable relationship. This may be established by demonstrating

It can also be concluded that the necessary and sufficient that the level of the organizational variable varies with the

conditions for a contingency perspective have been established environment in which the organization operates (see Table 5).

by showing that: (1) each strategy type is associated with Table 5 has two sets of F-ratios, the ratios in column 5

distinctively different levels of organizational variables (micro-test hypotheses that strategy types have significantly different

Table 5. Difference Among Strategic Types in Organizational Variables

Strategy Types (Means)

P A D R F-ratio Different Setsd

Market orientation

Regulated 4.02 3.33 3.51 2.49 3.90b P, D & A.R

Transitional 4.39 4.55 2.92 4.01 2.64 A & P.D

Open market 4.43 3.08 3.90 3.03 4.83b P.R & A

F-ratio 0.72 6.23b 2.11 1.91

Planning capability

Regulated 3.95 3.52 3.95 2.24 1.69

Transitional 4.54 3.78 2.29 2.80 1.55

Open market 4.21 2.00 3.72 2.71 3.94c P & D.A

F-ratio 0.26 1.90 1.90 0.15

Human resource management

Regulated 4.90 4.21 4.77 4.03 3.91c P & D.A & R

Transitional 5.16 5.07 4.55 4.24 1.08

Open market 4.96 3.78 4.51 3.45 6.78a P.R & A; D.R

F-ratio 0.38 6.70b 0.40 0.97

Managerial style

Regulated 3.16 3.75 3.41 2.89 0.87

Transitional 4.40 4.26 4.46 4.33 0.08

Open market 4.70 3.06 3.76 2.32 10.71a P.D, A & R; D

F-ratio 7.20a 1.78 2.35 6.63b

Innovation

Regulated 5.85 5.25 4.61 5.44 3.69b P, R & A.D

Transitional 6.54 5.91 5.43 4.43 2.25 P.R

Open market 6.66 4.90 5.33 6.03 7.31a P.A & D

F-ratio 1.60 2.88 2.59 1.73

Operating efficiency

Regulated 4.91 4.63 4.33 4.00 1.89

Transitional 4.87 4.68 4.38 4.11 1.15

Open market 4.62 4.74 4.38 4.00 1.44

F-ratio 0.68 0.06 0.02 0.01

ap,0.001. bp,0.01. cp,0.05.

dAbbreviations: P5Prospector; A5Analyzer; D5Defender; R5Reactor.

in different environmental states (macrocongruency) as argued and other resources required to develop the distinctive compe-tencies, technologies, structures and management processes by Fry and Smith (1987).

needed to pursue a particular strategy is large. . . . Perhaps Is the Miles and Snow (1978) typology equally applicable

the greatest obstacle to strategic change stems from the fact to the three environments? To answer this question each

orga-that over time a given strategy attracts and fosters a set of nizational variable was compared across the environments.

managerial values and philosophies that are wedded to the The size of the F-ratio was used as the test statistic (Table 5,

strategy” (p. 529). column 6). The results in Table 5 suggest that the general

pattern of differences across the strategy types holds in all

Environment, Strategy Type, and

environments. However, the largest differences occur in the

Organizational Performance

open market environment followed by the regulated

Table 6. ANOVA Model: Environment–Strategy Type Interaction

Strategy–Environment

Variables Full Model Strategy Type Environment Interaction

Return on assets 5.584a 2.187 1.4120a 3.203b

Growth in sales 1.009 1.293 1.095 0.708

New product success 3.432a 3.422c 4.530c 2.523c

Market share change 2.227c 0.299 7.619a 0.953

Exports 2.298c 2.193 4.079c 2.256c

Figures in the table are F-ratios.

ap,0.001. bp,0.01. cp,0.05.

dictors of organizational performance. This is in line with our To test Hypotheses 8a, 8b, and 8c in view of the above, ANOVA model and one-way ANOVA (using Duncan’s multi-conceptualization of the environment as degree of regulation

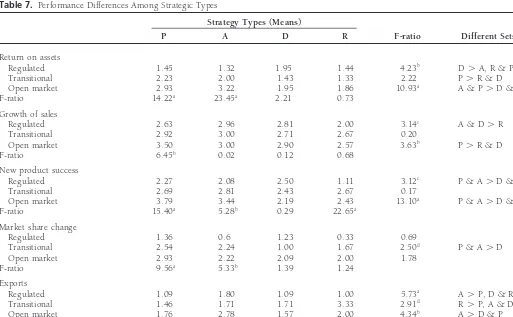

which should have performance implications. Further, the ple range test of means) were used (Table 7).

Hypothesis 8a, which states that performance under regula-results suggest that the interaction terms for environment

and strategy are generally significant across the performance tion should favor defenders is supported for return on asset, sales growth, and successful new product development. The measures. These results suggest that the environment as

de-fined in this article is a quasi-moderator (Sharma, Durand, Duncan’s test of means across the strategy types, indicates that defenders significantly outperform the other strategy and Gur-Arie, 1981).

Table 7. Performance Differences Among Strategic Types

Strategy Types (Means)

P A D R F-ratio Different Setse

Return on assets

Regulated 1.45 1.32 1.95 1.44 4.23b D.A, R & P

Transitional 2.23 2.00 1.43 1.33 2.22 P.R & D

Open market 2.93 3.22 1.95 1.86 10.93a A & P.D & R

F-ratio 14.22a 23.45a 2.21 0.73

Growth of sales

Regulated 2.63 2.96 2.81 2.00 3.14c A & D.R

Transitional 2.92 3.00 2.71 2.67 0.20

Open market 3.50 3.00 2.90 2.57 3.63b P.R & D

F-ratio 6.45b 0.02 0.12 0.68

New product success

Regulated 2.27 2.08 2.50 1.11 3.12c P & A.D & R

Transitional 2.69 2.81 2.43 2.67 0.17

Open market 3.79 3.44 2.19 2.43 13.10a P & A.D & R

F-ratio 15.40a 5.28b 0.29 22.65a

Market share change

Regulated 1.36 0.6 1.23 0.33 0.69

Transitional 2.54 2.24 1.00 1.67 2.50d P & A.D

Open market 2.93 2.22 2.09 2.00 1.78

F-ratio 9.56a 5.33b 1.39 1.24

Exports

Regulated 1.09 1.80 1.09 1.00 5.73a A.P, D & R

Transitional 1.46 1.71 1.71 3.33 2.91d R.P, A & D

Open market 1.76 2.78 1.57 2.00 4.34b A.D & P

F-ratio 2.76 3.54c 3.91c 15.62a

aP,0.001. bP,0.01. cP,0.05. dP,0.10.

types. For other performance measures the hypothesis is not mental change and uncertainty, perform poorly as a result, and then become reluctant to act aggressively in the future” supported. HenceH8areceives partial support.

Hypothesis 8b, which posits that under transitional condi- (p. 90). The proposition that reactors follow inconsistent strat-egies is supported by lack of planning capability. Effective tions the successful strategy type will be the analyzer, was

generally supported for most performance measures although planning presupposes the existence of planning goals that the firms seek to achieve. The characterization of the reactor is less only statistically significant for market share changes. Thus

H8b receives partial support. Hypothesis 8c, which posits that precise in the literature. Invariably it has been considered a repository for organizations that could not be classified else-prospectors would perform optimally in a free environment,

is supported. The results are statistically significant for all where. Conant et al. (1990) suggest that the reactor could be a stable type characterized by being “consistently inconsistent” measures of performance except market share changes. These

findings do not support equifinality (Miles and Snow, 1978) in its product market. In some environments the reactor organi-zations may succeed by rigging the solutions to problems. but lend support to Hooley et al. (1992).

Does performance differ by environment for each strategy The general proposition of equifinality of performance for the stable strategy types (prospectors, analyzers, and defend-type? The results of comparing each strategy type across

differ-ers) as proposed by Miles and Snow (1978) should be rejected ent environments, as would be expected, indicate significant

in favor of a contingency approach. Some strategy types per-differences (row 4 for each performance measures in Table

form better in certain environments. The results of this re-7). The conclusion to be drawn from these results is that

search imply that defenders outperform other strategy types organizational performance is enhanced by a more open and

under a regulated environment. This environment can be competitive business environment.

considered stable and organizational performance primarily depends on operational efficiency and an ability to read

socio-Discussion and Implications

political trends. The results also suggest that defenders mayperform poorly in turbulent environments. Analyzers would These results suggest that the Miles and Snow typology is an

generally outperform defenders and reactors in transitional effective framework for investigating the strategies followed

settings and under open market conditions. Prospectors per-by firms in the food manufacturing industry in Zimbabwe.

form well in transitional and open market conditions. The prospectors show distinct competence in marketing and

have more organic management styles. This agrees with

orga-Public Policy Implications

nization theory which suggest that when tasks are not routine,

Regulation appears to depress organizational performance. an organic management style should be followed (Walker and

This may have undesirable consequences for investment in Ruekert, 1987; Miles and Snow, 1978). The prospectors show

plant and equipment and employment generation especially distinct competence in planning. Scanning the environment

in developing economies. The firms most seriously affected is a critical requirement for a market-oriented organization

by regulation are those that are externally oriented as evi-that seeks to understand and proactively position itself for

denced by the poor performance of prospectors under regula-market changes.

tion. The implications are that the firms most likely to succeed Defender organizations show a superior score on operating

either as exporters or product innovators are the most seriously efficiency. This is the general findings of other researchers.

affected by regulation. Following deregulation, performance In line with search for operational efficiency, the management

improves in terms of return on assets and successful new style in defender organizations is mechanistic. The defenders

product introduction. The improvement in performance is score high on planning capability. In this case, the purpose

observed for all the strategy types except defenders. Firms of of planning is to enable organizational integration as distinct

the same strategy type operating in different environments from prospectors for whom planning permits adaptation to

have significant differences in performance suggesting the en-environmental dynamics.

vironment is an important determinant of organizational per-Analyzers show distinctive competence in innovation. Top

formance. From a public policy perspective, it is important management is constantly on the alert for technological (both

to note that firms do not change their strategies and character-process and product) developments. This enables the analyzer

istics quickly in response to regulatory changes. In the short to imitate quickly and be “second in” with products on the

term, many firms may actually become misaligned to the market. The management style is moderately mechanistic. This

environment and hence perform poorly as exemplified by is consistent with the need for efficiency while maintaining

defenders in this study. entrepreneurship in newer ventures. In other key variables

the analyzers behave like hybrids between prospectors and

Managerial Implications

defenders (Nicholson, Rees, and Brooks-Rooney, 1991). This

environ-culture of internal orientation and superior operating effi- (a) Predict future trends (b) Anticipate surprises (c) Improve response flexibility (d) Identify new businesses (e) Identify ciency should seek opportunities afforded by regulatory

envi-ronments (secure markets and predictable cashflows). Perfor- key problem areas (f) Generate new ideas (g) Integrate func-tions (h) React to competitor moves (i) Predict future customer mance in other environments would be relatively poorer.

Under a transitional environment, organizations that balance neds (j) Evaluate alternatives (k) Enhance management devel-opment

the need for efficiency and adaptive capability outperform

other strategy types on most performance measures. Manage- Source: Ramanujam and Venkatraman (1987). ment that combines the need for efficiency and adaptive

capa-Innovation a 5.8468

bility should find the period following deregulation most

ad-Marketing tried product 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 vantageous. However because the environment is transitional,

No of new products (last 5 years) this should provide opportunities for sharpening their

adap-Minor product changes tive capability to improve competitiveness as the industry

Responds to competitor moves evolves toward an open market. Under open market

condi-Rarely the first with new products tions, organizations that have the highest adaptive capability

Proclivity to low risk projects outperform other strategy types. The results suggest that the

Incremental behaviour benefits of external orientation outweigh the costs. As Stalk,

Emphasis on R&D and Innovation leadership Evans, and Shulman (1992) state: in the 1990s successful

Very many new products in 5 years companies will be those that are able to respond quickly to

Dramatic product changes customer or market demands and see the competitive

environ-Initiates innovation competition ment clearly, thus anticipate and respond to customers’

evolv-Often the first with new products ing needs and wants and adapt simultaneously to many

differ-Proclivity to high risk projects ent business environments.

Bold new initiatives Adaptability and responsiveness are crucial as Fink, Beak,

Source: Covin, Prescott, and Slevin (1990) (modified) and Taddeo (1971) pointed out. Extremely adaptive and

re-sponsive Japanese firms, have, through their sustained innova- Human Resources Management a 5.7876

tion, created such market turbulence that they have driven To what extent is your company have or perform the following: their rivals into self-destructive modes of decision making and (15 not at all, 75to a very great extent).

market behavior–that is, organizational nervous breakdown. (a) Effective personnel policies (b) Model employer (c) Em-ployee education (d) Design effective reward system (e)

Effec-Contribution to Research

tiveness of grievance procedures (e) Stimulate employee self-education (f) Value relations with trade unionsThis study extends the application of the Miles and Snow

Source: Narver and Slater (1990) typology by examining it in a developing economy. The results

of this study suggest that the environment is a homologizer

Managerial Style a 5.8400

in the relationship between strategy and organizational

vari-In general senior management favors (1 5 not at all, 7 5

ables but a quasi-moderator in the strategy–performance

rela-to a very great extent). tionship. It is therefore not enough for researchers to state

Formal—informal that the environment is a moderator without accurately

speci-Procedure—Objectives driven fying how it moderates the relationship. The study examines

Uniform—Free ranging managerial styles equifinality in the performance of the stable strategy types

Adherence—situation determines job performance and rejects it in favor of a contingency perspective through

Source: Covin, Prescott, and Slevin (1990) establishing the necessary and sufficient conditions for a

con-tingency theory in the context of this study. Operating Efficiency a 5.6857

Relative to competitors to what extent does your business have advantages in (15not at all, 75to a very great extent.

Appendix A

Cost efficiencyCost of sales Market orientation a 5.9216

Economies of scale achieved (a) Customer orientation (6 items)

Performance Measures (b) Competitor orientation (4 items)

a. Return on assets (ROA) (c) Interfunctional Coordination (5 items)

Net income (or loss)/total assets. Averaged over three years Source: Narver and Slater (1990)

1990–92 (or 1991–93) b. Growth in sales (SALES) Planning Capability a 5.8694

(St112St/St(sales in timet11 divided by sales timet)

To what extent is your planning system capable of contributing

Distinctive Marketing Competences and Organisational

Perfor-Sales($) (of products introduced in the last three years)/Total

mance: A Multiple Measures-Based Study.Strategic Management

Sales($) average of 3 years

Journal11 (1990): 365–383.

d. Market share changes

Covin, J. G., Prescott, J. E., and Slevin, D. P.: The Effects of

Techno-(MSt132MSt)/MStwhere MStand MSt13are market share in logical Sophistication on Strategic Profiles, Structure and Firm 1990 and 1993, respectively. Performance.Journal of Management Studies(1990).

Strategic type: This was based on responses to seven items: (3 Daft, R. L., Sormunen, J., and Parks, D.: Chief Executive Scanning, entrepreneurial; 2 engineering; and 2 administrative) derived Environmental Characteristics, and Company Performance: An from the distinctive characteristics of the Miles and Snow Empirical Study.Strategic Management Journal4 (1988): 137–151.

strategic types Dess, G. G., and Origer, N. K.: Environment, Structure and

Consen-sus in Strategy Formulation: A Conceptual Integration.Academy

Source: Conant, Mokwa, and Varadarajan (1990).

of Management Review(April 1987): 313–330.

Dickson, P. R.: Towards a General Theory of Competitive Rationality.

References

Journal of Marketing56 (January 1992): 69–83. Abernathy, W. J., and Wayne, K.: Limits of the Learning Curve.

Har-Doty, H. D., Glick, W. H., and Huber, G. P.: Fit, Equifinality and

vard Business Review52 (September–October 1974): 109–119.

Organisational Effectiveness Test of Two Configurational Theo-Aldrich, H. E.:Organisations and Environments, Prentice-Hall,

Engle-ries.Academy of Management Journal36 (1993): 1196–1250. wood Cliffs, NJ. 1979.

Drazin, R., and Van de Ven: Alternative Forms of Fit in Contingency Andrews, K. R.:The Concept of Corporate Strategy, Dow Jones-Irwin,

Theory.Administrative Science Quarterly30 (1985): 514–539. Homewood, IL. 1971.

Fink, S. L., Beak, J., and Taddeo, K.: Organisation Crisis and Change. Baldwin, William: Creative Destruction.Forbes(July 13, 1987): 49–50.

Journal of Applied Behavioral Science7 (1) (1971): 15–37. Barney, J. B.: Organisational Culture: Can it Be a Source of Sustained

Fiol, C. M., and Lyles, M. A.: Organisational Learning.Academy of

Competitive Advantage?Academy of Management Review, 11 (1986):

Management Review10 (4) (1985): 803–813. 656–665.

Frazier, G. L., Spekman, R., and O’Neal, C. R.: Just-in-Time Exchange Bhide, A.: Hustle as Strategy.Harvard Business Review64 (September–

Relationships in Industrial Markets. Journal of Marketing 52 October 1986): 59–65.

(1988): 52–67. Boeker, W.: Strategic Change: The Effects of Founding and History.

Fry, L. W., and Smith, D. A.: Congruence, Contingency and Theory

Academy of Management Journal32 (1989): 489–515.

Building.Academy of Management Review12 (1987): 117–132. Boeker, W., and Goodstein, J.: Organisational Performance and

Adap-Garvin, D. A.: Building a Learning Organisation.Harvard Business

tation: Effects of Environment and Performance on Changes in

Review71 (July/August 1993): 78–91. Board Composition.Academy of Management Journal34 (1991):

Ginsberg, A., and Buchholtz, A.: Converting to For-Profit Status: 802–826.

Corporate Responsiveness to Radical Change.Academy of

Manage-Bourgeois, L. J. III: Strategy and Environment: A Conceptual

Integra-ment Journal33 (1990): 445–477. tion.Academy of Management Review5 (1980): 25–39.

Gresov, C., and Drazin, R.: Equifinality: Functional Equivalence in Bourgeois, L. J., and Eisenhardt, K. M.: Strategic Decision Processes

Organisation Design.Academy of Management Review22 (1997): in High Velocity Environments: Four Cases in Computer Industry.

403–428.

Management Science34 (1988): 816–835.

Gupta, A. K., and Govindarajan, V.: Knowledge Flows and the Struc-Bower, J. L., and Hout, T. M.: Fast-Cycle Capability for Competitive

ture of Control Within Multinational Corporations.Academy of

Power.Harvard Business Review66 (November–December 1988):

Management Review16 (4) (1991): 768–792. 110–118.

Hambrick, D. C.: Operationalising the Concept of Business-Level Brittain, J. W., and Freeman, J.: Organisational Proliferation and

Strategy in Research. Academy of Management Review5 (1980): Density Dependent Selection, inThe Organisation Life Cycle: Issues

567–576.

in the Creation, Transformation, and Decline of Organisations, J. R.

Hambrick, D. C.: Some Test of the Effectiveness and Functional Kimberly and R. H. Miles, eds., Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Attributes of Miles and Snow’s Strategic Types.Academy of

Man-1980, pp. 291–338.

agement Journal26 (1) (1983): 5–26. Burns, T., and Stalker, G.:The Management of Innovation. Tavistock

Hamel, G., and Prahalad, C. K.:Competing for the Future. Harvard Publications, London. 1961.

Business School Press, Boston, MA. 1994. Cameron, K. S., and Whetten, D. A.:Organisational Performance: A

Hannan, M., and Freeman, J.: Structural Inertia and Organisational

Comparison of Multiple Models. Academic Press Inc., New York.

Change.American Sociological Review29 (1984): 149–164. 1983.

Hannan, M. T., and Freeman, J.: The Population Ecology of Organis-Carroll, G. R.: Concentration and Specialisation: Dynamics of Niche

ations.American Journal of Sociology83 (1977): 929–984. Width in Populations and Organisations.American Journal of

Soci-ology90 (1985): 1262–1283. Henderson, B. D.: Application and Misapplication of the Experience Curve.Journal of Business Strategy4 (Winter 1984): 3–9. Chakravarthy, B. S.: Adaptation: A Promising Metaphor for Strategic

Management.Academy of Management Review7 (1982): 35–44. Hooley, G. J., Lynch, J. E., and Jobber, D.: Generic Marketing Strate-gies.International Journal of Research in Marketing9 (1992): 75–89. Collis, D. J.: A Resource Based Analysis of Global Competition: The

Case for the Bearings Industry.Strategic Management Journal12 Hrebiniak, L. K., and Joyce, W. F.: Organisational Adaptation:

Strate-(1991): 49–68. gic Choice and Determinism.Administrative Science Quarterly30