Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Building a Competency-Based Curriculum

Architecture to Educate 21st-Century Business

Practitioners

Seung Youn Chyung , Donald Stepich & David Cox

To cite this article: Seung Youn Chyung , Donald Stepich & David Cox (2006) Building a Competency-Based Curriculum Architecture to Educate 21st-Century Business Practitioners, Journal of Education for Business, 81:6, 307-314, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.81.6.307-314

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.81.6.307-314

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 150

View related articles

ABSTRACT. Competency-based

instruction can be applied to a military

set-ting, an academic program, or a corporate

environment with a focus on producing

per-formance-based learning outcomes. In this

article, the authors provide theoretical and

practical information about underlying

characteristics of competencies and explain

how the Department of Instructional &

Per-formance Technology at Boise State

Uni-versity developed a set of competencies and

has been modifying its curriculum on the

basis of these competencies. The

depart-ment’s curriculum architecture flowchart

illustrates the process of developing and

applying competencies to curriculum

design for producing performance-based

learning outcomes. Detailed steps taken in

developing a competency-based course are

described.

Copyright 2006 Heldref Publications

he interest in competency-based instruction has been growing for several decades (e.g., Gillies & Howard, 2003; Gordon & Issenberg, 2003; James, 2002). As a result, many organizations are purchasing learning management systems that include a built-in competency model-ing function (e.g., GeoLearnmodel-ing, http:// www.geolearning.com/; Meridian KSI, http://www.meridianksi.com). Whether competency-based instruction is applied to a military setting, an academic pro-gram, or a corporate environment, the common denominator is the focus on per-formance-based learning outcomes.

Competency-based learning and per-formance strategies have been empha-sized in the Human Performance Tech-nology (HPT) field as well. Several professional organizations, such as the International Society for Performance Improvement (ISPI), the American Society for Training and Development (ASTD), and the International Board of Standards for Training and Perfor-mance Instruction (IBSTPI), have established standards to promote com-petency-based performance improve-ment in industry (see http://www.ispi .org, http://www.astd.org, and http:// www.ibstpi.org). In this article, we provide theoretical and practical infor-mation about the underlying character-istics of competencies and the process of developing and applying competen-cies to curriculum design.

What Is a Competency?

IBSTPI defines a competency as “a knowledge, skill, or attitude that enables one to effectively perform the activities of a given occupation or function to the standards expected in employment” (International Board of Standards for Training and Performance Instruction, 2005). The National Center for Educa-tion Statistics (NCES) of the U.S. Department of Education (2002) defines a competency as “the combination of skills, abilities, and knowledge needed to perform a specific task” (p. 7). As defined by both IBSTPI and NCES, a competency includes both means and an end. The meansare knowledge, skills, or abilities and the endis to effectively per-form the activities of a given occupation or function to the standards expected in employment. The term competencyloses its true meaning if the end is ignored.

The specific purpose of using compe-tencies in curriculum design for employee development is to increase the possibility of transforming learning experiences into performance-based organizational outcomes. The core of competency-based curriculum design is to ensure that learners will be able to demonstrate their learned capabilities after they have acquired a necessary combination of knowledge, skills, and abilities. For this reason, competency-based instruction is often referred to as

Building a Competency-Based Curriculum

Architecture to Educate 21st-Century

Business Practitioners

SEUNG YOUN (YONNIE) CHYUNG DONALD STEPICH

DAVID COX

BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY BOISE, IDAHO

T

performance-based instruction (Naquin & Holton, 2003) and being able to demonstrate (therefore, evaluate) such outcomes is the key to competency-based instruction.

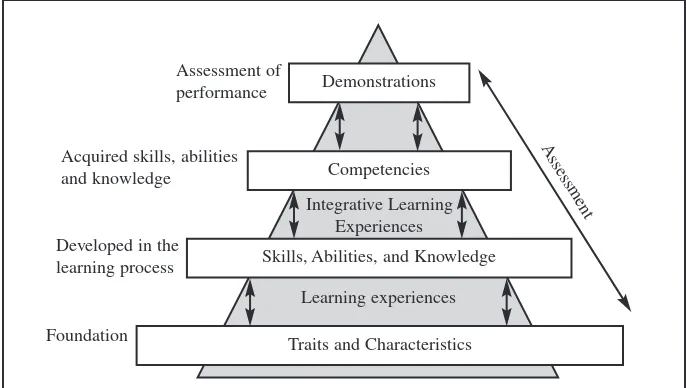

For example, Figure 1 shows the four-step conceptual learning model adopted by the NCES that illustrates necessary elements and processes for being able to acquire and demonstrate competencies. It is important to note three aspects of the NCES model: (a) the competencies are built upon the foundation of the person’s traits and characteristics through selective and collective learning experiences; (b) the assumption is made that each level shown in the model is measurable; and (c) the ultimate goal is to be able to demonstrate the outcomes of learned competencies.

The Underlying Characteristics of Competencies

When developing a competency-based curriculum, it is important to address the following aspects of competencies.

Skill-Based vs. Competency-Based Instruction

It is important to remember that not all skill-based instruction is necessarily competency-based. A competency goes beyond a skill. It is not only about what

one knows and can do but also whether one is able to accomplish a task and produce an outcome that is valued by both oneself and the organization. Competencies are strategically linked to organizational goals. For this reason, Spencer and Spencer (1993) used the word causally in their definition of competency, “an underlying character-istic of an individual that is causally related to criterion-referenced effective and/or superior performancein a job or situation” (p. 9, italics in original), indi-cating that a competency is intended to cause or predict a specific, desired per-formance outcome. Therefore, a goal of providing competency-based instruc-tion is to increase human competence, which should be measured not solely by the behavior but by the worthiness of the outcomes of that behavior (Gilbert, 1978).

Competent vs. Expert

Being competent is not necessarily the same as being an expert. H. Dreyfus and S. Dreyfus (1986) and S. Dreyfus (2004) have suggested that adults progress through five stages as they develop professional skills: (a) novice; (b) advanced beginner; (c) competent; (d) proficient; and (e) expert. Gillies and Howard (2003) described six levels of performance based on Benner’s

adaptation (1984) of Dreyfus and Drey-fus’ 1980 model: (a) unskilled or not relevant; (b) novice; (c) learner; (d) competent; (e) proficient; and (f) expert. The six levels of the perfor-mance model help one to visualize the progress of individuals from unskilled to expert. However, it is important to understand the difference between being competent and being expert, not only for designing adequate means to help individuals reach a competent level but also to appropriately evaluate their performance outcomes. Compe-tency-based instruction is designed to help an individual reach a competent level, and the individual may continue to acquire his or her proficiency and expertise through additional learning and work experiences.

Context-Specific Competencies

Although there has been an effort to develop a competency dictionary that identifies and describes generic com-petencies used in a wide range of jobs (Spencer & Spencer, 1993), competen-cies in real practice are rather context specific. For example, managers in the field of health care may need to acquire a set of competencies, which may not be entirely applicable to supervisors working on the factory floor of an automobile manufacturing company. Also, even if competent leadership is required in both cases, the type of lead-ership that a manager of a nursing home needs may not be the same as the type of leadership necessary on the automobile factory floor. The result is a need to develop different sets, and sometimes even different definitions, of competencies for the different con-texts. This creates a need for organiza-tions to develop their own competency-based curriculum architecture with a specific competency dictionary. Spencer and Spencer also recognized this aspect of competencies and have clearly pointed out that “the generic dictionary scales are applicable to all jobs and none precisely” (p. 23).

Adopting Competencies in Curriculum Design

Adoption of competencies in curricu-lum design requires a paradigm shift in Demonstrations

Competencies

Skills, Abilities, and Knowledge

Traits and Characteristics Learning experiences

Integrative Learning Experiences Assessment of

performance

Acquired skills, abilities and knowledge

Developed in the learning process

Foundation

Assessment

FIGURE 1. A hierarchy of postsecondary outcomes.From Defining and Assessing Learning: Exploring Competency-Based Initiatives, by the National Center for Education Statistics, 2002,

http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2002/2002159.pdf, p. 8.

thinking and planning. Job-related com-petenciesimplicitly refer to a combina-tion of relevant behaviors and qualities necessary to perform a specific job, rather than a set of individual, segment-ed behaviors, which may or may not be closely aligned with the job specifica-tions or requirements. A competency is also learner- or performer-oriented rather than instructor- or manager-ori-ented. In this sense, the focus in training and management during the early 20th century was away from performer-ori-ented competencies (Cooper, 2000). For example, methods used in Taylor’s (1911/1998) scientific management and military training during the world wars advocated a management-centric approach in which tasks and strategies were highly segmented to reduce the complexity of the required job and to maximize the efficiency of work process. Learners or performers were expected to follow a series of behaviors to complete a job, and their input on designing the series of behaviors was minimal. However, the quality manage-ment movemanage-ment, the increasing empha-sis on improving human potential in various fields, and especially McClel-land’s (1973) effort to change the focus from testing for intelligence to testing for competence, have helped shift cur-riculum design toward adopting a learn-er- or performlearn-er-centered, competency-based approach.

Competency-based curriculum design is based on systems thinking and strate-gic planning (Naquin & Holton, 2003), and it can be applied to various settings including educational school systems (James, 2002), professional apprentice-ship training programs (Gordon & Issenberg, 2003), corporate universities, and military programs (Ellison, 2001). However, there are several barriers to adopting competency-based models in curriculum design.

Measurability

The crucial element in competency-based models is the use of criterion-ref-erenced, measurable assessment meth-ods. In other words, if you cannot measure it, it probably is not a compe-tency (Voorhees, 2001). This character-istic of competencies has pros and cons.

A competency-based model provides all stakeholders (e.g., managers, employ-ees, instructors, and students) with a clear roadmap of the destination and how to reach it. However, it can over-simplify the complex nature of human learning processes and is based on an assumption that all human learning can be overtly and accurately measured.

Resistance

The use of standards in the process of engineering learning experiences and measuring performance outcomes may produce a negative impression that it produces corporate androids, rather than innovators, reflective knowledge work-ers, or problem solvers (James, 2002). Poorly designed assessment methods can add to this negative impression.

Time-Consumption

It is a very time-consuming task to build the architecture for a competency-based curriculum. This is because mul-tiple competencies need to be assem-bled and individual competencies must be built on one another with a result that competencies support the institution’s strategic goals. It is costly to identify and carry out an employee development plan for each individual employee based on his or her competencies (Dubois & Rothwell, 2004).

Designing a Competency-Based HPT Curriculum Architecture

The HPT field has slowly gained in popularity over the last several decades and many higher educational institu-tions are currently offering HPT courses or a degree program designed with spe-cific competencies in mind (Klein & Fox, 2004; Schwiebert, Marmon, Micone, & Cox, 2003). The goal of higher education institutions is not only to help students learn certain behaviors and transfer them to job-related tasks, known as near transfer, but also to pre-pare students to perform competently when opportunities arise in the future, known as far transfer (Perkins, 1995). To accomplish this, academic institu-tions use a broad range of assessments to identify the competencies that will help students prepare for future work.

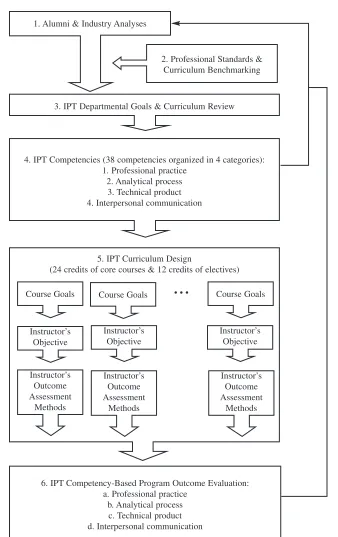

For example, the Instructional and Performance Technology (IPT) depart-ment at Boise State University offers a master’s degree to a student body made up mostly of HPT practitioners. Over the past 3 years, the IPT department at Boise State has developed a list of competen-cies and has been modifying the curricu-lum based on these competencies. Figure 2 is a flowchart that shows the overall process that the IPT department is using to develop its competency-based curricu-lum. Within this process, Steps 1, 2, 3, and 4 are about identifying the compe-tencies, Step 5 is about using those com-petencies in instructional planning and implementation, and Step 6 is about eval-uating the effectiveness of the resulting curriculum.

Step 1 was an alumni survey. Each year, university administrators conduct an alumni survey and provide the results to each department. For example, Appendix A shows the survey results obtained from IPT graduates in 2001. These results showed that the depart-ment curriculum was relatively effective in producing competency in some skills (e.g., drawing conclusions from data) and less effective in other skills (e.g., defining and solving problems). As a result the department administration formed a curriculum architecture (CA) committee consisting of the faculty and decided to develop a more comprehen-sive set of competencies and to use those competencies in a coordinated curriculum development effort.

Step 2 involved establishing profes-sional standards and curriculum bench-marking. The CA committee reviewed the competencies published by three professional organizations: ISPI, ASTD, and IBSTPI. In addition, the committee reviewed the curricula from four univer-sities that had academic programs simi-lar to the IPT curriculum. These reviews helped the committee formulate the ini-tial range of competencies that students should have upon graduation.

Step 3 was identifying departmental goals. The CA committee reviewed the stated goals of the IPT department and compared them to the competencies iden-tified in Step 2. This allowed the commit-tee members to add competencies that they considered important and that might be unique to the Boise State program.

Step 4 was generating a list of petencies. At this point, the CA com-mittee synthesized the skills, compe-tencies, and goals identified in Steps 1, 2, and 3 into a single set of statements that would describe the competencies that the IPT students should have when they graduated. This involved

elimi-nating redundant statements, combin-ing similar statements, and, in some cases, specifying new labels for com-petencies. The result was a list of 38 competencies grouped into four cate-gories: (a) professional practice; (b) analytical process; (c) technical prod-ucts; and (d) interpersonal

communi-cations. The full list of competencies is included in Appendix B. The commit-tee defined each competency to make them easier to understand and apply to course design, concluding the CA committee’s work.

Next, the department administration repeated Step 1, the alumni survey and industry analysis. Once the administra-tion identified competencies, the department used a Web-based system to survey alumni and professionals in the HPT industry. The department sent an e-mail solicitation to participate in the alumni survey to a departmental list-serv. Seventy-eight subscribers were IPT alumni at the time of the survey, and 31 of them responded, for a response rate of 39%. For the industry survey, the department sent e-mail solicitations to 80 industry representa-tives. Seventeen were rejected as unde-liverable, leaving 63 viable e-mail addresses. Twenty-two individuals responded to the survey, for a response rate of 35%. Both the alumni and indus-try surveys asked for demographic information (i.e., name, job title, employer, type of industry). Each sur-vey then asked respondents to rate, on a 5-point scale (1 = unimportant; 5 =

important), each of the 38 competen-cies on two dimensions: (a) how impor-tant they thought it was and (b) how frequently they used it. Finally, respon-dents were asked to identify any addi-tional competencies that they consid-ered important. A sample of the industry survey format is included in Appendix C.

On the industry survey, the mean rat-ing of each competency on both dimen-sions (importance and frequency) was greater than 3. That is, professionals in the field viewed all 38 competencies to be both important and frequently used at work. On the alumni survey, the mean rating of importance for each competen-cy was also greater than 3. However, 6 competencies received mean frequency ratings of less than 3. Those competen-cies were #13 model building and selec-tion (M= 2.61,SD= 1.33), #15 research (M = 2.97,SD = 1.52), #17 cost-effec-tiveness analysis (M= 2.90,SD= 1.60), #18 evaluation of intervention outcomes (M= 2.52,SD= 1.36), #26 development of noninstructional interventions

FIGURE 2. Information and Performance Technology (IPT) competency-based curriculum architecture flowchart.

1. Alumni & Industry Analyses

2. Professional Standards & Curriculum Benchmarking

3. IPT Departmental Goals & Curriculum Review

4. IPT Competencies (38 competencies organized in 4 categories): 1. Professional practice

2. Analytical process 3. Technical product 4. Interpersonal communication

5. IPT Curriculum Design

(24 credits of core courses & 12 credits of electives)

Course Goals Course Goals Course Goals

Instructor’s Objective

Instructor’s Objective

Instructor’s Objective

Instructor’s Outcome Assessment

Methods

Instructor’s Outcome Assessment

Methods

Instructor’s Outcome Assessment

Methods

6. IPT Competency-Based Program Outcome Evaluation: a. Professional practice

b. Analytical process c. Technical product d. Interpersonal communication

• • •

(M= 2.87,SD = 1.36), and #31 coping (M= 2.94,SD= 1.50). This suggests that the alumni used these competencies less often at work (see Appendix D).

Step 5 was redesigning courses. The department used the competencies to redesign the courses in the curriculum. The key to this ongoing process is to carefully align the stated course objec-tives, the competencies that apply to that course, and the graded course assignments. This requires two basic steps: (a) translating existing course goals into applicable competencies from the list developed in Step 4 and (b) developing course assignments that will both help students acquire those compe-tencies and assess the extent to which they have been successful. For example, Appendix E shows the objectives, com-petencies, and assignments for an online course on needs assessment.

Step 6 was performing a program evaluation to evaluate the effectiveness of the curriculum in helping students achieve the established competencies. The development of a competency-based curriculum is an on-going process that requires repeating the steps of ana-lyzing alumni and industry needs, reviewing relevant professional stan-dards, and re-examining departmental goals.

Summary

The centerpiece of a competency-based curriculum is the idea that a com-petency includes both means and an end. Therefore, the key to developing a competency-based curriculum is to focus on helping students translate their knowledge, skills, and abilities (means) into valued organizational outcomes

(ends). The architecture of a competen-cy-based curriculum builds on upfront strategic planning and requires ongoing evaluations of internal and external sources for developing competencies. As the IPT example illustrates, this can require a significant investment in time and effort. Curriculum planners must use various sources to identify desired competencies, develop learning experi-ences, and create corresponding assess-ment tools. However, in practical fields such as HPT, the payoff can be substan-tial. Students acquire not only knowl-edge, skills, and abilities but also the capability to use those knowledge, skills, and abilities in a variety of job-related situations.

NOTE

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Yonnie Chyung, EdD, Department of Instructional & Performance Technology, Col-lege of Engineering, Boise State University, Boise, ID 83725-2070.

E-mail: ychyung@boisestate.edu

REFERENCES

Benner, P. (1984). From novice to expert: Excel-lence and power in clinical nursing practice. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley.

Boise State University. (2002). Importance of skills and impact BSU had, sorted by mean importance: For students receiving graduate

degrees in 2000–2001 (Unpublished report).

Boise, ID: Boise State University, Institutional Analysis, Assessment, and Reporting. Cooper, K. (2000). Effective competency

model-ing and reportmodel-ing: A step-by-step guide for improving individual & organizational

perfor-mance. New York: American Management

Association.

Dreyfus, H., & Dreyfus, S. (1986). Mind over machine: The power of human intuition and expertise in the era of the computer. New York: Free Press.

Dreyfus, S. (2004). The five-stage model of adult skill acquisition. Bulletin of Science, Technolo-gy & Society, 24, 177–181.

Dubois, D., & Rothwell, W. (2004).

Competency-based or a traditional approach to training? T+D, 58(4), 46–57.

Ellison, D. (2001). The Navy has its own corpo-rate university. Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute, 127(9), 74–75.

Gilbert, T. (1978). Human competence:

Engineer-ing worthy performance. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Gillies, A., & Howard, J. (2003). Managing change in process and people: Combining a maturity model with a competency-based approach. TQM & Business Excellence, 14, 779–787.

Gordon, D., & Issenberg, S. B. (2003). Develop-ment of a competency-based neurology clerk-ship. Medical Education, 37, 484–485. International Board of Standards for Training and

Performance Instruction. (2005). Competen-cies. Retrieved July 27, 2004, from http://www.ibstpi.org/competencies.htm James, P. (2002). Discourses and practices of

competency-based training: Implications for worker and practitioner identities. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 21, 369–391. Klein, J., & Fox, E. (2004). Performance

improve-ment competencies for instructional technolo-gists. TechTrends, 48(2), 22–25.

McClelland, D. (1973). Testing for competence rather than for intelligence. American Psychol-ogist, 28, 1–14.

Naquin, S., & Holton, E., III (2003). Redefining state government leadership and management development: A process for competency-based development. Public Personnel Management, 32(1), 23–46.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2002). Defining and assessing learning: Exploring

competency-based initiatives (NCES

2002-159). Retrieved July 27, 2004, from http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2002/2002159.pdf Perkins, D. (1995). Outsmarting IQ: The

emerg-ing science of learnable intelligence. New

York: Free Press.

Schwiebert, P., Marmon, S., Micone, B., & Cox, D. (2003, April). Instructional and perfor-mance technology competencies: From identifi-cation to assessment. Paper presented at the 41st International Society for Performance Improvement (ISPI) Conference, Boston, MA. Spencer, S. M., & Spencer, L. M. (1993).

Compe-tence at work: Models for superior perfor-mance. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Taylor, F. (1998). The principles of scientific

man-agement. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications.

(Original work published 1911)

Voorhees, R. (Ed.) (2001). Measuring what mat-ters: Competency-based learning models in higher education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

APPENDIX A

Boise State University (BSU) Alumni Survey Results, 2000–2001

Information and Performance Technology (IPT) graduates who received graduate degrees in 2000–2001 rated the importance of 17 skills necessary for being personally or professionally successful on a scale of 1–4 (1 = no importance; 4 = major impor-tance). They also rated the extent of impact that Boise State University had in helping them achieve these skills on 4-point (1 = no impact; 4 = major impact) Likert-type scale. From Importance of Skills and Impact BSU had, Sorted by Mean Importance: For Students Receiving Graduate Degrees in 2000–2001, by Boise State University, 2002.

appendix continues

APPENDIX A—Continued

Number Mean Mean BSU

Skill responded importance impact

Defining and solving problems 13 3.92 2.92 Drawing conclusions from data 13 3.85 3.31 Using computers and other technology 13 3.77 3.38 Using effective oral communication 12 3.75 2.46 Using effective written communication 13 3.69 3.38 Meeting challenges in my career 13 3.69 3.15 Developing skills employers need 12 3.67 3.15 Developing effective leadership skills 13 3.62 2.62

Working as a team member 13 3.62 2.85

Committing to lifelong learning 13 3.54 3.23 Getting along with diverse people 13 3.54 2.31 Developing original ideas or products 13 3.46 3.08 Understanding humans and environment 13 3.31 2.46 Developing standards for my life 13 3.23 2.46 Acquiring well-rounded general education 13 3.23 2.77 Thinking objectively about beliefs 13 3.08 2.83 Learning about career options 13 2.77 2.46

APPENDIX B

Information and Performance Technology (IPT) Competencies

An IPT competency is a knowledge unit, a skill set, an attitude, or a personal char-acteristic that the IPT curriculum is designed to help students build. While completing the IPT degree program, students develop integrated multiple IPT competencies, which in turn help them improve their performance as professional instructional tech-nologists or performance techtech-nologists.

The 38 IPT competencies are organized into four categories as shown.

Professional practice Analytical process 1. Business or industry understanding 10. Analytic thinking

2. Results-oriented practices 11. Needs assessment and analysis 3. Value-adding practices 12. Data analysis

4. Systems view 13. Model building and selection

5. Leadership 14. Observation

6. Vision and goal setting 15. Research

7. Project management 16. Systematic problem solving 8. Consulting 17. Cost-effectiveness analysis 9. Professional and ethical judgment 18. Evaluation of intervention

outcomes

Technical product Interpersonal communication 19. Adult learning 29. Buy-in and advocacy 20. Computer-mediated communication 30. Coaching

skills 31. Coping

21. Writing skills 32. Delegation 22. Presentation skills 33. Facilitation 23. Design of instructional 34. Feedback

interventions 35. Group dynamics and group 24. Design of noninstructional process

interventions 36. Self-knowledge 25. Development of instructional 37. Social awareness

interventions 38. Work in partnership with clients 26. Development of noninstructional

interventions

27. Implementation of instructional interventions

28. Implementation of noninstructional interventions

APPENDIX C

Sample Industry Survey Questionnaire

The purpose of this questionnaire is to ensure that Boise State University’s Instruction-al and Performance Technology (IPT) department’s curriculum supports industry needs. This survey takes approximately 10–15 minutes to complete and the data will be used to assess how the competencies are used in specific industries and to improve our pro-gram's offerings. Thank you in advance for your participation.

Name (optional): _____________ Title/Position: _____________

Employer: _____________

Industry: (select from a drop-down menu) If other, please list: _____________

How important are the following competencies to your work? Please rate each compe-tency according to its importance in your work and how often you use it.

1. Business or industry understanding: To identify how functional systems of orga-nizations (organizational strategies, structural elements, power or knowledge networks, financial position, and organizational cultures) work.

• How important is this competency to your job? Unimportant 1 2 3 4 5 Important

• How often do you use this competency? Rarely 1 2 3 4 5 Often

2. Results-oriented practices: To differentiate means and ends, to establish measurable ends-oriented goals, and to employ means that make changes and lead to desired end results.

• How important is this competency to your job? Unimportant 1 2 3 4 5 Important

• How often do you use this competency? Rarely 1 2 3 4 5 Often (Statements of IPT competencies #3–38 use the same format)

Are there any additional competencies that are important to your work? Do you have any other feedback for the IPT department?

APPENDIX D

Results of Alumni and Industry Surveys

Alumni (n= 31) Industry (n= 22)

Importance f Importance f

Competency M SD M SD M SD M SD

1 3.90 1.30 3.35 1.40 4.00 1.31 4.00 1.11

2 4.52 0.81 3.94 1.21 4.27 1.03 4.14 0.94

3 4.48 0.96 3.87 1.41 4.10 0.94 4.14 0.96

4 4.41 0.91 3.94 1.18 4.36 0.90 4.09 1.02

5 4.48 0.68 3.90 1.19 4.27 0.88 4.09 1.02

6 4.03 1.11 3.39 1.31 3.82 1.18 3.64 1.43

7 4.60 0.72 4.33 0.92 4.36 0.73 4.23 1.02

8 4.27 0.98 3.67 1.42 4.14 0.83 3.82 1.18

9 4.42 0.92 3.65 1.36 4.32 0.95 3.95 1.05

10 4.55 0.85 3.94 1.18 4.41 0.91 4.45 0.96

11 4.48 0.77 3.58 1.31 4.18 0.80 4.00 1.02

12 4.19 0.87 3.61 1.31 3.95 1.05 3.86 1.25

13 3.52 1.29 2.61 1.33 3.18 1.05 3.00 1.31

14 4.03 0.87 3.39 1.17 4.00 0.87 3.77 1.27

15 3.74 1.18 2.97 1.52 3.68 1.32 3.55 1.47

16 4.48 0.93 3.74 1.46 4.00 1.11 4.00 1.11

17 4.00 1.34 2.90 1.60 3.45 1.14 3.05 1.13

18 3.97 1.22 2.52 1.36 3.91 1.23 3.32 1.25

19 4.30 0.79 3.73 1.28 4.18 1.14 3.95 1.33

20 4.10 1.16 3.52 1.63 3.77 1.38 3.86 1.28

appendix continues

APPENDIX D—Continued

Alumni (n= 31) Industry (n= 22)

Importance f Importance f

Competency M SD M SD M SD M SD

21 4.50 0.97 4.29 1.16 4.36 0.85 4.45 0.86

22 4.63 0.67 4.03 1.19 4.32 0.78 4.52 0.81

23 4.42 0.85 3.42 1.34 4.19 1.12 4.00 1.30

24 4.27 0.94 3.16 1.27 3.77 1.41 3.68 1.55

25 4.03 0.91 3.16 1.34 4.09 1.19 3.95 1.33

26 3.97 1.16 2.87 1.36 3.59 1.40 3.14 1.64

27 4.10 1.11 3.13 1.59 3.90 1.18 3.33 1.46

28 4.06 0.96 3.00 1.29 3.36 1.36 2.82 1.53

29 4.19 1.19 3.35 1.50 4.09 0.97 3.86 1.17

30 4.13 1.11 3.39 1.48 4.09 0.75 3.68 1.09

31 3.90 1.01 2.94 1.50 3.32 1.25 3.09 1.48

32 3.87 1.26 3.42 1.29 3.68 1.29 3.50 1.47

33 4.13 1.06 3.58 1.41 3.95 0.90 3.95 1.00

34 4.58 0.67 3.81 1.38 4.18 0.80 4.09 1.06

35 4.33 0.80 3.52 1.50 3.82 1.01 3.77 1.19

36 4.03 1.08 3.52 1.41 3.62 1.16 3.41 1.40

37 3.97 1.14 3.00 1.51 3.19 1.25 3.18 1.40

38 4.40 1.07 4.10 1.35 4.32 0.89 4.09 1.34

APPENDIX E

Objectives, Competencies, and Assignments for a Needs Assessment Course

Course objectives

Describe a problem or opportu-nity and its dimensions

Select and use appropriate data gathering tools and techniques

Determine the possible causes of a problem and recommend both instructional and noninstruction-al solutions, where appropriate

Explain important concepts, principles, and models related to needs assessment

Competencies

Professional practice • Systems view • Project management • Consulting

Analytical process • Analytical thinking

• Needs assessment and analysis • Data analysis

• Systematic problem solving

Technical products • Writing skills

Interpersonal communication • Work in partnership with

clients

Assignments

Needs assessment project in which students are expected to gather data related to the causes of an existing or anticipated per-formance problem, make data-based recommendations to solve the problem, and present their recommendations in a written report

Data gathering methods report in which students are asked to inform the rest of class about a method that is commonly used to gather needs assessment data

Participation in class discussions in which students discuss con-cepts and principles described in assigned readings