Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 13 January 2016, At: 00:26

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

A Meta-Analytic Examination of Kolb's Learning

Style Preferences Among Business Majors

Robert Loo

To cite this article: Robert Loo (2002) A Meta-Analytic Examination of Kolb's Learning Style Preferences Among Business Majors, Journal of Education for Business, 77:5, 252-256, DOI: 10.1080/08832320209599673

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320209599673

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 229

View related articles

A

Meta-Analytic Examination of

Kolb’s Learning Style Preferences

Among Business Majors

ROBERT LOO

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

University of Lethbridge Lethbridge, Alberta,

Canada

t is widely recognized that education-

I

al achievement depends not only on the intellectual ability and aptitude of the learner but also on the individual’s learning style (Kolb, 1984). “Learning style” refers to the consistent way in which a learner responds to or interacts with stimuli in the learning context. Closely related to cognitive styles, learning styles are intimately related to the learner’s personality, temperament, and motivations. Riding and Cheema (1991) noted that the concept of learn- ing styles seems to have emerged in the 1970s as a replacement for that involv- ing cognitive styles. Several investiga- tors have examined these two constructs concerning individual differences and their conceptual relationships (Moran,1991; Riding

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Cheema, 1991). Activi-ty in the learning styles field has been so strong that some 21 different models have been developed (Curry, 1983).

Kolb’s Model of Experiential Learning

Kolb’s well established experiential learning model (ELM) has attracted much interest and application. His model is founded on Jung’s concept of types or styles through which the individual develops by using higher level integra- tion and expression of nondominant modes of dealing with the world (Kolb, 1984). Experience is translated into con-

ABSTRACT. In this article, the author used a meta-analytic approach

and

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Kolb’s Learning Style Inventoryto investigate business students’ learn- ing style preferences. In a review of

1,791 cases from 8 studies, he found

small to moderate effect sizes in style preferences for the pooled data and for

2 of 3 majors (accounting, finance,

and marketing) examined. The author presents recommendations concerning the importance of learning styles and varied teaching methods and discusses the need for large-sample studies with more detailed reporting of participant demographics.

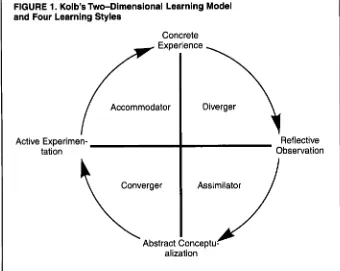

cepts that, in turn, guide the choice of new experiences (see Figure 1). Learning is conceived as a four-stage cycle starting with concrete experience, which forms the basis for observation and reflection on experiences. These observations are then assimilated into concepts and gener- alizations that guide new experiences and interactions with the world.

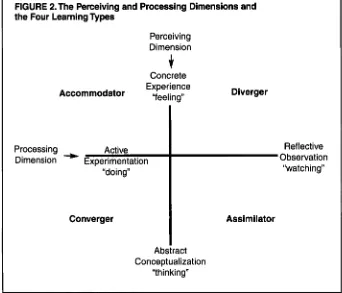

This model reflects two independent dimensions based on (a) perceiving, which involves concrete experience (feeling) and abstract conceptualization (thinking), and (b) processing, which involves active experimentation (doing) and reflective observation (watching). These two dimensions form the follow- ing four quadrants reflecting four learn- ing styles (see Figure 2): accommoda- tor, diverger, assimilator, and converger. Kolb (1985) described accommodators

as people who learn primarily from “hands-on” experience and “gut” feel- ings rather than from logical analysis. Divergers are best at viewing concrete situations from many different points of view. Assimilators are best at under- standing a wide range of information and putting it into a concise and logical form, and convergers are best at finding practical uses for ideas and theories. The effective learner can use each of the four styles in different learning situa- tions rather than only relying on his or her preferred style.

The Learning Styles Inventory

Kolb (1976) developed the 12-item self-reported Learning Styles Inventory (LSI) to assess learning styles. Tbelve short statements concerning learning situations are presented, and respon- dents are required to rank-order four sentence endings that correspond to the four learning styles. Kolb (1985) later refined the LSI, resulting in the LSI-1985 version, which incorporated some improvements (i.e., the internal- consistency reliabilities).

Use of Learning Styles in Business Education

Many investigators (Holley & Jenk- ins, 1993; Kolb, 1976, 1984) have used learning styles instruments to describe

252

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

JournalzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education forzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

BusinessFIGURE 1. Kolb’s Two-Dimensional Learning Model

and Four Learning Styles

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Concrete

Active Experimen- Reflective Observation Assimilator

alization

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

students and to correlate learning styles with a wide variety of variables related to academic and vocational interests, performance, and the like. Underlying such work is the view that specific edu- cational experiences (e.g., accounting education) are a major factor in the development or accentuation of certain learning styles because of the “profes- sional mentality” being developed (e.g., accounting standards of practice, ways of perceiving problems, and acceptable kinds of solutions). Consequently, cer- tain styles are considered characteristic of specific educational choices and pro- fessions. For example, Kolb (1 976, 1984) reported that accommodators are often found in business disciplines. On the other hand, in their combined sam- ple of 222 business undergraduates from two universities, Reading-Brown and Hayden (1989) found that converg- ers were most common (3 1 %), followed by assimilators and divergers (25% each) and accommodators (19%).

Some researchers examined the dis- tinct majors within the business disci- pline. The accounting major appears to have drawn the most attention. Baldwin and Reckers (1984) administered Kolb’s LSI to two samples of accounting stu-

dents

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

( n = 172 and 187) and found thatthe inventory distinguished between

groups the had different styles (e.g., accounting students versus accounting faculty members). Baker, Simon, and Bazeli (1986) examined the learning styles of 110 accounting majors and found that twice as many fell into the

converger style

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

( n = 43) as into theaccommodator ( n = 24), diverger ( n =

21), or assimilator ( n = 22) styles. In a larger study, Brown and Burke (1987) examined the learning styles of business undergraduates, including 267 account- ing majors. They found that accounting majors indicated no marked preference

for one style over another.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

In a morerecent study, Holley and Jenkins (1 993) examined the learning styles and grades of 49 intermediate accounting students. Their scatter plot of LSI scores (their Figure 2, p. 303) revealed that 26 of the 49 students fell into the assimilator quadrant, 10 into the diverger, 8 into the converger, and 5 into the accommodator quadrant.

Although styles business research based on breakdowns by majors has focused primarily on accounting majors, at least one study also focused on other business majors. Brown and Burke (1987) found that assimilators formed the largest style category (30.4%) among finance majors ( n = 89) and that divergers formed the largest

style category (36.1%) among market- ing majors ( n = 83).

It is interesting to note that business researchers and educators have recog- nized the importance of learning styles for learners and for teachers and have used a variety of teaching or learning methods (Ronchetto, Buckles, Barath, &

Perry, 1992; Wynd & Bozman, 1996). Unfortunately, the current literature has either largely neglected majors other than accounting or relied on the broader distinction between hard (e.g., finance) and soft (e.g., human resource manage- ment) majors (Becher, 1989; Macfar- lane, 1994). Similarly, business researchers apparently have not exam- ined the possibility of gender differences in learning styles among business stu- dents. Given the increase in the number of women entering business schools, such an examination would be helpful.

Finally, another criticism of the state of the business literature is that many researchers have used relatively small sample sizes, especially given that these samples must be subdivided among the four styles. For example, Holley and Jenkins (1993) used only 49 partici- pants. Findings from such small sam- ples do not give us confidence in the generalizability of results to the greater population of business students. Brown and Burke (1987) used a more adequate sample size ( n = 439) for examining the distribution of styles.

Purposes of the Study

My main purpose in this study was to more accurately estimate the distribu- tion of learning styles in the broader population of business students. My secondary purpose was to examine the learning styles of specific business majors in cases in which adequate data were available.

Method

Selection

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of StudiesI conducted a computer-based search of the SSCI and ERIC databases from 1976 to June 1999 for empirical studies that relied on either the original 1976 version or the revised 1985 version of Kolb’s LSI. Only those studies that

May/June 2002 253

[image:3.612.45.385.48.319.2]FIGURE 2. The Perceiving and Processing Dimensions and

the Four Learning Types

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Perceiving Dimension

Concrete Experience

Accommodator 6yeeling,, Diverger

Processing Active

Dimension Experimentation

“doing”

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

-

Converger

Ab Concep

Reflective Observation

“watching”

Assimilator

act dization “thinking”

focused on college or university students in business or management majors or courses and that reported the actual fre- quency or percentage distribution for the four learning styles were selected. The search identified seven studies meeting these criteria along with my unpublished

study, which had 424 cases.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Coding

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I recorded the frequency counts and percentages for each of the four styles for each sample. In cases in which samples were broken down by business majors, I

also recorded the frequency counts and percentages for each of the four styles for each specified major. Although variables and breakdowns by sex, age, and other demographic variables would have been desirable, such information was rarely provided in the studies.

Calculation

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Effect SizesGiven the null hypothesis that the fre- quency counts of business students are equally distributed among the four learning styles, a chi-square test for the goodness of fit would provide the appropriate effect size index (Cohen,

1992, Table 1, p. 157).

With k-1 degrees of freedom and where P,, is the actual frequency of cases falling in the first learning style,

Poi is the expected frequency of cases

for that style, and k is the number of cat- egories or styles in this study.

Resu I ts

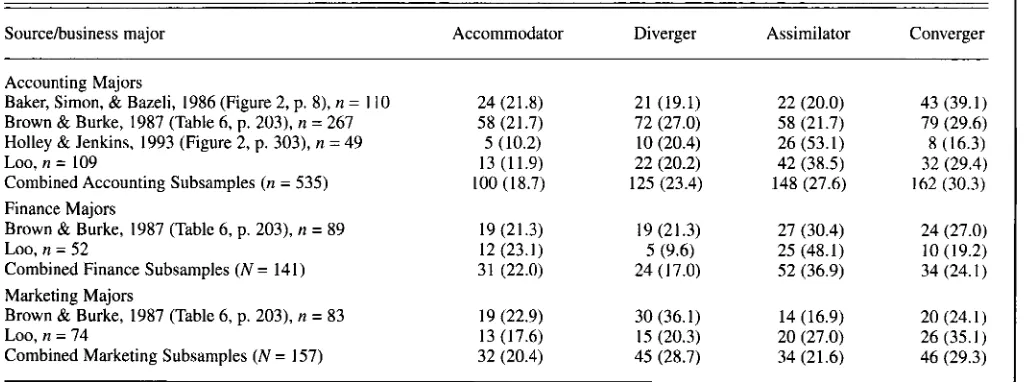

In Table 1, I present the frequency

counts and percentages for the four learning styles for the eight studies. Similarly, in Table 2 I present the find- ings organized by business majors.

The Distribution

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Learning Style PreferencesThe chi-square test for goodness of fit under the null hypothesis that the four learning styles are equally distributed was significant for the pooled data from all seven studies

(x2

= 19.29, df = 3, p <.Ol). I performed Z tests for the differ- ence between proportions to pinpoint the sources of the significant chi-square. There was a significantly higher propor-

tion of assimilators ( Z = 3.19,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

p < . O l )and a lower proportion of accommoda- tors ( Z = -3.72, p < .01) than expected under the equal distribution hypothesis. There was a significant overall effect for the accounting subsample

(x2

=16.57, df = 3, p < .Ol): There was a higher proportion of convergers ( Z =

3.16, p < .01) and a lower proportion of accommodators ( Z = -3.74, p < . O I ) than expected under the equal distribu- tion hypothesis. There was also a signif- icant overall effect for the finance sub- sample

(x2

= 12.11, df = 3, p < .Ol), which had a higher proportion of assim- ilators ( Z = 2.92, p < .01) and a lower proportion of divergers (Z = -2.52, p <.05) than expected under the equal dis-

tribution hypothesis. Finally, the mar- keting subsample revealed an equal dis- tribution of styles

(x2

= 4.05, df = 3, p >.05).

Effect Sizes

Given the total sample size of 1,79 1

cases, this sample met the requirements for detecting a small effect size (ES) at

an alpha level of .01 and the general convention of .80 as a desirable level of power (Cohen, 1992, Table 2, p. 158). The obtained ES (4 = .104, df =3) for the pooled data from all samples revealed a small effect size given the cutoffs of .10 for small, .30 for medium, and .50 for large effect sizes for 4 (Cohen, 1992, Table 2, p. 158). The ES

for accounting (4 = .177, df = 3 ) and that for marketing (4 = .160, df =3) majors were also small, and the ES for finance majors (4 = .298, df =3) was barely moderate.

Discussion and Recommendations

This meta-analytic examination of eight studies showed that Kolb’s learning styles were not equally distributed among the business majors in this sam- ple. I found a higher proportion of assim-

ilators and lower proportion of accom- modators than would be expected if styles were equally distributed. The pooling of frequency data from these studies resulted in a total sample size of

1,791 cases, which meets the require- ments for detecting even a small ES at an alpha level of .01 and the general con-

254

[image:4.612.44.386.45.338.2]TABLE 1. The Distribution of Learning Styles for Business Students

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Source Accommodator Diverger Assimilator Converger

Baker, Simon, &

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Bazeli, 1986 (Figure 2, p. 8) ( nzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

= 110)Brown & Burke, 1987 (Table 6, p. 203)

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

( n = 439)Gardner & Korth, 19981 ( n = 178)

Holley & Jenkins, 1993 (Figure 2, p. 303) ( n = 49)

Loo, present study ( n = 424)

Reading-Brown & Hayden, 1989 (n = 222)

Togo & Baldwin, 1990 (Table 4, p. 197) ( n = 218)

Yuen & Lee, 1994 (Table 2, p. 547) ( n = 151)

Combined business samples ( n = 1,791)

24 (21.8) 96 (21.9) 62 (35)

5 (10.2)

75 (17.8) 42 (19) 43 (19.7) 36 (23.8) 383(21.4) 21 (19.1) 121 (27.6) 38 (21) 10 (20.4) 87 (20.0) 56 (25) 70 (32.1) 28 ( 1 8.5) 431 (24.1)

22 (20.0) 99 (22.5) 49 (27) 26 (53.1) 149 (35.4) 56 (25) 59 (27.1) 49 (32.5) 509 (28.4) 43 (39.1) 123 (28.0) 29 (16) 8 (16.3) I13 (26.8) 68 (31) 46 (21.1) 38 (25.2)

468 (26.1)

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

[image:5.612.62.566.59.193.2]Nore. Only percentages rounded to whole numbers are reported in the article.

TABLE 2. The Distribution of Learning Styles for Business Majors

Sourcebusiness major Accommodator Diverger Assimilator Converger

Accounting Majors

Baker, Simon, & Bazeli, 1986 (Figure 2, p. 8), n = 110

Brown & Burke, 1987 (Table 6, p. 203), n = 267

Holley & Jenkins, 1993 (Figure 2, p. 303), n = 49

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

LOO, n = 109

Combined Accounting Subsamples ( n = 535)

Finance Majors

Brown & Burke, 1987 (Table 6, p. 203), n = 89

Loo, n = 52

Combined Finance Subsamples ( N = 141)

Marketing Majors

Brown & Burke, 1987 (Table 6, p. 203), n = 83

Loo, n = 74

Combined Marketing Subsamples ( N = 157)

24 (21.8)

58 (21.7)

13 (11.9)

100 (18.7)

19 (21.3) 12 (23.1) 31 (22.0) 19 (22.9) 13 (17.6) 32 (20.4) 5 (10.2) 21 (19.1) 72 (27.0)

10 (20.4)

22 (20.2) 125 (23.4)

19 (21.3)

5 (9.6)

24 (17.0)

30 (36.1)

15 (20.3)

45 (28.7) 22 (20.0) 58 (21.7) 26 (53.1) 42 (38.5) 148 (27.6) 27 (30.4) 25 (48.1) 52 (36.9) 14 (16.9) 20 (27.0) 34 (21.6) ~~

43 (39. I )

79 (29.6) 8 (16.3) 32 (29.4) 162 (30.3) 24 (27.0) 10 (19.2)

34 (24. I )

20 (24. I ) 26 (35.1) 46 (29.3)

Note. Percentages for each row variable are presented in brackets following the frequency count.

vention of .80 as a desirable level of

power (Cohen, 1992, Table 2, p. 158). Thus, this study overcame the issue of the reporting of results from a sample of inadequate size to detect a reliable distri- bution of styles. Furthermore, the pool- ing of data from several studies reporting the styles breakdown by business majors enabled a preliminary examination of

three majors: accounting ( n = 535),

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

mar-keting ( n = 157), and finance ( n = 141). Still, these three subsample sizes are not quite large enough to meet the require- ments noted earlier for detection of small effects. Clearly, meta-analyses of Kolb’s styles among business students would be facilitated if researchers provided their data in the form of frequency counts for each style for as many majors as is prac- tical and by gender.

Even though there was an effect for styles in this study, there was much diversity among business students and within specific majors. Thus, like other researchers (Collins & Milliron, 1987; Drew & Ottewell, 1998; Kolb, 1984), I recommend that educators encourage students to use all four learning styles appropriately. Rather than relying on a preferred style, students should use a wide range of learning methods. Svinicki and Dixon (1987) presented different teaching methods that fit the different learning types. For example, simulations and field work could fit nicely with active experimentation (doing), whereas keeping a journal or log could fit with reflective observation (watching). There appear to be substan- tial benefits to students who develop

the ability to adopt different learning styles in different situations, recognize their own learning strengths and prefer- ences, and approach learning situations with flexibility.

REFERENCES

Baker, R. E., Simon, J. R., & Bazeli, F. P. (1986). An assessment of the learning style preferences of accounting majors. Issues in Accounting

Education, Spring, 1-12.

Baldwin, B. A., & Reckers, P. M. I. (1984). Exploring the role of learning styles research i n accounting education policy. Journal of

Accounting Education, 2(2), 63-76.

Becher, T. (1989). Academic tribes and territo- ries. Milton Keynes: Open University Press. Brown, H. D., & Burke, R. C. (1987). Accounting

education: A learning styles study of profes- sional-technical and future adaptation issues.

Journal of Accounting Education. 5, 187-206. Cohen, J. A. (1992). A power primer. Psychologi-

cal Bulletin, 112(1), 155-159.

Collins, J. H., & Milliron, V. C. (1987). A measure

May/June 2002 255

[image:5.612.58.572.264.455.2]of professional accountants’ learning style.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Issues in Accounting Education, Fall, 193-206. Curry, L. (1983). A critique of the research on

learning styles. Educational Leadership, 48(2), 50-56.

Drew, E,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Ottewell, R. (1998). Languages inundergraduate business education: A clash of learning styles. Studies in Higher Education,

Gardner, B.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

S., & Korth,zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

S . J . (1998). A frame-work for learning to work in teams. Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

ofEducation for Business, 74( I ) , 28-33. Holley, J. H., & Jenkins, E. K. (1993). The rela-

tionship between student learning style and per- formance on various test question formats.

Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education f o r Business, 68(5),301-308.

Kolb, D. A. (1976). Learning Style Inventory:

Technical manual. Boston: McBer.

Kolb. D. A. (1984). Experience as the source of

23(3), 297-305.

learning and development. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Kolb, D. A. (1985). The Learning Style Inventory:

Technical manual, Boston: McBer.

Macfarlane, B. (1994). Issues concerning the development of the undergraduate business studies curriculum in UK higher education.

Journal of European Business Education, 4.

Moran, A. (1991). What can learning styles research learn from cognitive psychology?

Educational Psychology, I1(3), 239-245.

Reading-Brown, M. S., & Hayden, R. R. (1989). Learning styles-liberal arts and technical train-

ing: What’s the difference? Psychological

Reports, 64, 507-5 18.

Riding, R., & Cheema, I. (1991). Cognitive styles-An overview and integration. Educa-

tional Psychology, 11(3), 193-215.

Ronchetto, J. R., Buckles, T. A., Barath, R. M., & 1-14.

Perry,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

J. (1992). Multimedia delivery systems:A bridge between teaching methods and learn- ing styles. Journal of Marketing Education.

Svinicki, M. D., & Dixon, N. M. (1987). The Kolb learning model modified for classroom activi- ties. College Teaching, 35(4), 141-146. Togo, D. F., & Baldwin, B. A. ( I 990). Learning

style: A determinant of student performance for the introductory financial accounting course.

Advances in Accounting. 8, 189-199. Wynd, W. R., & Bozman, C. S. (1996). Student

learning style: A segmentation strategy for higher education. Journal f o r Education for Business, 71(4), 232-235.

Yuen, C., & Lee, S. N. (I 994). Applicability of the Learning Style Inventory i n an Asian context and its predictive value. Educational und Psy-

chological Measurement, 54(2), 54 1-549.

I4(1), 12-21.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Advertise in the

Journal of

Education for Business

For more information please contact:

Alison Mayhew, Advertising Director

Heldref Publications

1319 Eighteenth St

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

N W

Washington.

DC

20036-1 802

Phone:

(202) 296-6267

ext.

247

Fax:

(202) 296-5149