A

CCOUNTABILITY

: T

HE

O

RIGINS

, S

TATE

AND

I

MPLICATIONS OF

S

HOPFLOOR

D

EMOCRACY WITHIN THE

C

ONGRESS OF

S

OUTH

A

FRICAN

T

RADE

U

NIONS

GEOFFREYWOOD*

T

he present paper explores the extent of internal democracy and grassroots partici-pation within the Congress of South Africa Unions, focusing specifically on questions of shopfloor organisation and the office of shopsteward, and is based on a nation-wide survey of members of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU). The survey revealed remarkably high levels of participation within union internal structures, and deeply embedded notions of accountability and recall.INTRODUCTION

A particular characteristic of union organisation in many anglophone countries is the key role played by the shopsteward or workplace representative. Generally elected by her or his peers, the shopsteward is both a union official and an employee within a unionised enterprise. A particular source of strength to South Africa’s independent unions has been strong shopfloor organisation and democracy, centering on the office of the shopsteward. Based on a nationwide survey of trade union members, the present paper explores the current nature and extent of shopfloor democracy in South Africa’s largest union federation, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU).

ORIGINS OF THE SHOPSTEWARD SYSTEM INSOUTHAFRICA

Worker organisation in South Africa began in 1841, with the formation of a trade protection society by printers (Lewis 1984, p. 18). The discovery of gold in 1886 led to the rapid growth of trade unions on the British model (including the establishment of shopfloor representation centering on shopstewards), but with one important difference: African workers were excluded. The resultant unions were faced with a dilemma: should they protect their interests through a reliance on skill and collective action, or through racial solidarity? The history of these unions is a complex one, punctuated by periodic outbreaks of militancy,

most notably the General Strike and Rebellion of 1922. However, by the 1950s, almost all had chosen the path of conservatism, and in an historic compromise with capital, traded off militancy for job protection of racial lines.

Black trade unionism in South Africa has its origins in the Industrial and Commercial Workers Union of Africa (ICU), founded in 1919 (Bonner 1978). The ICU expanded rapidly, but had a ‘random and disorganized membership’, including labour tenants and rural peasants (Lewis 1984, p. 46). Power was centralised, making endemic leadership disputes even more damaging. This, and a lack of an effective policy agenda, resulted in the ICU effectively collapsing by the late 1920s, although it enjoyed a modest revival in the urban centre of East London in the late 1940s and 50s. Subsequent efforts to organise Africans, most notably under the umbrella of the Federation of Non-European Trade Unions and, subsequently, the Council of Non-European Trade Unions (CNETU) were similarly, albeit not so spectacularly, unsuccessful. This reflected sustained employer resistance, a lack of legal rights, and a reliance on a small coterie of leaders. For example, the defeat of the 1946 African miner’s strike dealt CNETU’s organisation a fatal blow, leading to a dramatic decline in membership and a bitter round of leadership struggles (Sutcliffe and Wellings n.d., p. 7).

to establishing ‘the shopsteward structure as the key link between management and the shopfloor’ (Webster 1987a, p. 25). On the Witwatersrand, the Industrial Aid Society established the Metal and Allied Workers Union (MAWU). After initially impressive membership gains, MAWU virtually collapsed by the close of the decade, in the face of managerial opposition and bitter internal struggles (Maree 1987a, p. 6). However, the union’s recovery was secured by concentrating on the building of intensive shopfloor organisation, again with the shopsteward playing a central role (ibid. p. 6). In the Western Cape, the Western Province Workers Advice Bureau (WPWAB) again recorded impressive gains followed by setbacks. As was the case with other organisational initiatives, the latter represented the product of strategic errors, managerial opposition, as well as broader developments, including the start of an economic downturn, and the wave of state repression that followed the 1976 Soweto uprising. Once more, WPWAB rebuilt itself by placing a strong emphasis on elected factory representatives, and transformed itself into the Western Province General Workers Union (Maree 1987a, p. 5).

Meanwhile, a grouping of officials formerly employed by the conservative Trade Union Council of South Africa (TUCSA) established the Urban Training Project (which, again, focused it attention on organising black workers) in the Witwatersrand region. Again, this project led to the establishment of a number of unions: unions that were particularly badly hit by the post-1976 Soweto wave of repression (Maree 1987a, p. 5). However, this underscored the importance of building a strong base in the factories.

In placing a strong emphasis on the need for effective shopfloor organisation, the new ‘independent’ trade unions were not only informed by the experience of SACTU (which highlighted the need for effective organisation at grassroots level in order to weather state repression), but also that of the British labour move-ment. The years 1968 to 1974 represented the high water mark of the expan-sion of union density in Britain (Kelly 1998, p. 91). This wave of mobilisation (albeit reflecting changes in the wider economy) was partially driven by the prominent role of––and continuing increase in the numbers of workplaces organised with––shopstewards (ibid. p. 96), and provided an inspiring example for those seeking to promote trade union development in South Africa (see Maree 1987a, p. 2–3).1In 1979, a new federation, the Federation of South African Trade Unions (FOSATU) was formed, incorporating the TUACC unions, some former Urban Trading Project Unions, and the revitalised national MAWU.

The 1970s also saw the emergence of a number of overtly political unions with formal links to political organisations: the ‘populist’ unions. Most notably, the Black Allied Workers Union (BAWU) was founded by Black Consciousness-orientated students on the Reef as an umbrella union dedicated to organising all industrial workers (Friedman 1987, p. 44). However, BAWU soon encom-passed workers who did not necessarily support Black Consciousness, leading to BAWU’s transformation into the non-racial South African Allied Workers Union (SAAWU) in 1979. Despite its political origins, SAAWU again accorded a central role to shopstewards; although, feedback (in some cases, imperfect) was given to members via mass meetings (Maree 1987b, p. 36–7). SAAWU’s political activities––above all, opposing the ‘independence’ of the Ciskei homeland––resulted in repressive action by the authorities (including the murder of SAAWU activists). However, Maree (1987b, p. 37) argues that ‘too much reliance had been placed . . . on the union’s leader’s for many of its activities’, making it particularly vulnerable to repression (even though the strongest shopfloor structures would have battled to withstand the sheer brutality of the Ciskeian regime). This resulted in SAAWU being more prag-matic in its dealings with the workerist unions.

In 1985, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) was launched, bringing together the FOSATU unions, a number of non-aligned unions, populist unions such as SAAWU, and the massive National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), which had defected from the black-consciousness aligned Council of Unions of South Africa. Following on this, SAAWU disbanded, its membership being divided into new industrial unions that centred on the former FOSATU industrial unions. The NUM was an industrial union, and already had established shaft steward structures on its entry to COSATU as founder affiliate (Baskin 1991, p. 50; Friedman 1987, p. 387). A factor that facilitated union unity was that, even in workerist unions, shopstewards were often also active in local community campaigns as well; many had a direct interest in pursuing both factory organisation and community struggle simultaneously (c.f. Friedman 1987, p. 452–72). While an important dividing factor between community groupings and unions was that often between representatives of the unemployed and the employed (Friedman 1987, p. 453), in other cases––above all mining towns––key workplaces embodied the community. Even in some regions of high unemploy-ment, major employers––notably motor manufacturers and steel plants––formed a central focus for communities, according workplace leaders a stature both inside and outside the factory.

1990s as the unions had to contend with the new challenges of democratisation and economic adjustment (c.f. Barchiesi 1999, p. 22). Nonetheless, internal shopfloor democracy remained vibrant throughout the 1990s, providing a powerful check on managerial autonomy (Bohmke and Desai 1996; Barchiesi 1999, p. 25). At the same time, ‘the exodus of experienced union leaders (at all levels) towards political positions in the ANC and government’ has weakened the capacity of the labour movement (Barchiesi 1999, p. 25). This capacity can; however, be regenerated by effective shopfloor democracy, drawing up a new generation of leaders from the grassroots, especially because COSATU shop-stewards “have been historically aware” of the need for transparency, leadership accountability and the possibility of recall (ibid. p. 25).

Prior to 1995, shopstewards in South Africa had no statutorily delineated rights; although, within individual workplaces, they may have negotiated enforceable rights in terms of a union recognition agreement (Government GazetteNo. 16861 1995). In terms of the 1995 Labour Relations Act, in any workplace where a repres-entative trade union (i.e. one that has organised a majority of employees at a work-place) has at least ten members, these members are entitled to elect ‘trade unions representatives’ from amongst their ranks (ibid.). Depending on the size of the workforce, this number may vary from one (in the case of 10 or less than 10 union members) to 20. Shopstewards are entitled to legal protection against victimis-ation, and have the right to represent employees in grievance and disciplinary proceedings and to monitor the employer’s compliance with any law relating to the terms and conditions of employment and legally binding collective agree-ments. In addition, they have the right to carry out any functions agreed upon by the representative union and management (ibid.). Shopstewards are further entitled to ‘reasonable’ paid time off during working hours to perform the functions of a trade union representative, and for further training relevant to the performance of her/his functions as a representative (ibid.).2

The 1995 Labour Relations Act also made provision for a second form of workplace representation, via ‘workplace forums’, the equivalent of European work councils. These forums have been generally eschewed by unions, reflecting concerns that they might trigger off demarcation disputes and erode the trad-itional role of shopstewards (Wood and Mahabir 2001, p. 241).

South Africa’s historical experience continues to shape the organising strate-gies of unions. Drawing on the experiences of unions overseas and the failure of previous attempts at mass unionisation, the independent unions remain committed to retaining the office of shopsteward. There is similarly a general consensus concerning the importance of a vibrant shopfloor democracy. Less clear; how-ever, is the extent to which this is, and can be, maintained and reconstituted in a context of broader socio-economic change.

METHOD

of members. Sample size was determined largely by the diversity of a population. The final sample size was calculated after the administration of a pilot study prior to the survey. It should be emphasised that there was a high degree of uniformity in responses to key questions, cutting across gender, age and skill; in short, respon-dents represented a relatively homogenous grouping (Wood and Psoulis 2001, p. 299). The pilot studies also facilitated greatly in the final structuring and layout of the questionnaire and, in the case of the first survey, in the elimination of difficult-to-understand or ambivalent questions.

Given potentially important geographic variations, area sampling was employed. The country was divided into a number of key areas (Western Cape, Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng) where the bulk of South African industry (and, indeed, the country’s overall population) is concentrated. In each of these strata, key sectors were encompassed (e.g. the metal industry, the chemical industry, etc.). A serious limitation of this method is that the sample size within each strata (e.g. the Western Cape) has to be representative, necessi-tating a somewhat larger sample size than would otherwise have been the case. The regional offices of each of the COSATU unions were contacted by the researchers, and support for the initiative was secured. Thereafter, individual employers were contacted, and access to workplaces was arranged. Employers were selected by means of Telkom4listings. Thereafter, employers were contracted to confirm that their hourly/weekly paid workers were represented by a COSATU union. The research project was a collaborative one, involving academics from a number of South African universities, including Eddie Webster, Johann Maree, David Ginsburg, Roger Southall, Shane Godfrey and the author.

wide range of parties, and the lack of accurate trade union membership lists, it represented the only feasible option under the circumstances. While it would have been easier to have interviewed workers attending union meetings, this would have course, eliminated those who were less active in union affairs. (Wood and Psoulis 2001, p. 293–314).

COMPREHENDING SHOPFLOOR DEMOCRACY: ISSUES AND INDICATORS

According to Olsonian theory of collective action, unions are ‘encompassing organisations’, members being subsumed into a general ‘mass’, leading to problems of representivity, and ultimately of maintaining mobilisation (Crouch 1982, p. 65). However, Crouch argues that in reality, unions are very much more face-to-face organisations, in which the contributions of individual members are of great importance in determining the strength of the group (ibid. p. 66). Indeed, a study conducted by Goldthorpe and Lockwood in the United Kingdom found that members tended to disassociate the national profile of the union (to which they had little input) with shopfloor democracy (most notably shopsteward elections) in which they took an active part (ibid. p. 66). Again, a 1994 survey by Kelly and Heery of union officials found that the degree of support they gave for strikes largely depended on their perceptions of workplace support and the potential for victory. In other words, shopfloor pressure played a central role in determining key union decisions at a local level, even if it may entail financial costs for the national union. However, vibrant shopfloor organisation does not seem to necessarily lead to the fragmentation of unions on localised lines, owing to the reliance shopstewards placed on the union for advice and help, and because they needed ‘the legitimacy of its recognition to enhance their own standing with management’ (Batstone in Crouch 1982, p. 66). In short, the shopfloor may be central to the making of trade union identity, with localised sub-cultures determining membership profiles and plant-level strategic choices.

leadership may be out of touch with the material conditions of communities, while the latter may not necessarily have full knowledge of macro-economic trends and/or the overall performance of specific industries. This can result in real tensions between conciliatory leaders and a more radical grassroots: a ‘demo-cratic rupture’. The conservative response is simply to suggest that national unions could do more to reign in ‘disorderly’ local activists (Boraston et al.1975, p. 195). However, there are other ways in which this gap may be bridged; moreover, reigning in shopfloor activists may be very difficult, and may result in union organisation being damaged severely (ibid. p. 195–6), as borne out by the experi-ences of NUM of South Africa during the Mercedes-Benz and Volkswagen disputes.5In the end, this is bound up with questions of power: to what extent can union members make their views felt within the union, and to what extent can they immediately recall leaders that have been perceived to have departed from their brief? Again, this is considerably easier at a shopfloor rather than a national level. However, if there are strong horizontal linkages (i.e. if unions rely on grassroots solidarity across workplaces when engaging in collective action) officials are likely to have a wider range of local contacts, and be more in touch with local debates (Kelly 1988, p. 170).

Two closely interrelated issues set South Africa apart from Britain and the rest of the Anglo-Saxon world. First, there is the racial dimension. South Africa expanded its domestic industrial sector under heavy state protectionism in the post WW2 period, with a policy of active import substitution; what set the coun-try apart from other industrialising countries was a rigid racial division of labour, that is sometimes referred to as ‘racial fordism’ (Rogerson 1991, p. 356). Africans were excluded from a wide range of semi-skilled and skilled occupations, and up until 1979, were excluded from official collective bargaining structures. The per-sistence of racial segregation within and without the workplace in the 1980s pre-cluded the government from politically incorporating the unions (Webster 1987b); the emergence and consolidation of a radical shopfloor tradition owes much to this. However, the complex nature of racial segregation sowed further divisions within the working class among oppressed groupings as a result of unequal access to resources. Such divides included that between ‘coloured’ (i.e. mixed racial origin) and Indian workers. Second, there is a spatial one: a system making widespread use of migrant labour and hostels resulted in a particularly close link between work and residence for many workers. While this inevitably led to some tensions with township dwellers,6it also facilitated a common solidarity forged around shared experiences of discrimination, including insecurity of abode (c.f. Rogerson 1991, p. 359–60).

a mass base) and shopstewards (who rely on the union for legitimacy). Third, a strong shopfloor democracy means that union officials are likely to be more aware of localised concerns. This leads us to the question of how shopfloor democracy, and the extent and constraints on a ‘democratic rupture’ with regional and national leadership, may be measured.

First, there is the extent of horizontal linkages within and between unions at grassroots level; in other words, the extent of mutual support that workers lend each other (and indeed, the exchange of ideas) at grassroots level (Kelly 1988, p. 170). Invariably drawn into a coordinating role, officials are more likely to be aware of grassroots concerns and debates under such a scenario (ibid.). In the survey, this is measured by the extent to which respondents had direct experience of receiving concrete support from other unions or community organisations when engaging in collective action.

Second, there is the question of ‘remoteness’ (Kelly and Heery 1994). In other words, do union members see national leadership––and indeed, the leadership of allied political organisations––as somehow distinct from workplace organis-ation, subject to different rules, and not bound by the same degree of account-ability? This is measured in the survey by the extent to which union members see political leaders as bound by the need to report back, and subject to recall if need be.

Third, while much of the contemporary literature on the possibility of a Michelsian ‘iron law of oligarchy’ being in force focuses on tensions between shopfloor activists and national leadership, it is possible that shopstewards themselves can constitute an oligarchic elite (Crouch 1982, p. 182). The obvious check on such a development would be if shopstewards can be readily deposed by their constituents if they fail to carry out their wishes, and whether this regu-larly takes place in reality (see ibid.). In the survey, respondents were asked if they believed if shopstewards should be subject to recall if they exceeded their brief, and whether they had personal experience of having deposed a shopsteward.

Fourth, there is the question of whether unions can escape the ‘Olsonian trap’ playing a national role of limited local relevance, or whether they remain face-to-face organisations, with high levels of grassroots participation in their internal life (Crouch 1982, p. 65). This is measured by the extent to which respondents regularly attended union meetings.

Finally, there is little doubt that the global trend is towards greater diversity in the workforce; while there continue to be good reasons for workers to unite, there are powerful centripetal tendencies. Many writers have highlighted the differences in experiences workers may bring to the workplace, and the vital need to overcome gender, skill and age divisions (see, for example, Moody 1997; Hyman 1992; Rogers 1995; Weinbaum 1999; Wood and Psoulis 2001).

FINDINGS

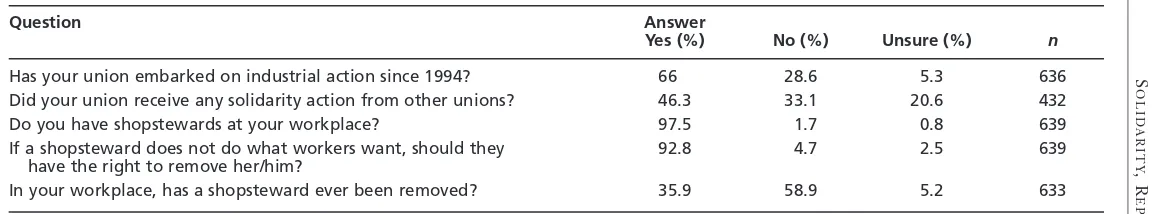

The responses to a range of key questions are summarised in Table 1.

S

OLIDARITY

,

R

EPRESENT

A

TIVITY

AND

A

CCOUNT

ABILITY

335

Question Answer

Yes (%) No (%) Unsure (%) n

Has your union embarked on industrial action since 1994? 66.0 28.6 5.3 636

Did your union receive any solidarity action from other unions? 46.3 33.1 20.6 432

Do you have shopstewards at your workplace? 97.5 1.7 0.8 639

If a shopsteward does not do what workers want, should they 92.8 4.7 2.5 639

have the right to remove her/him?

In your workplace, has a shopsteward ever been removed? 35.9 58.9 5.2 633

cleavages between different categories of respondents to a number of key questions dealing with or related to issues of shopfloor democracy. Where divisions proved to be statistically significant, they are presented in the form of cross-tabulations.

Horizontal linkages

As can be seen from Table 1, two-thirds of respondents had experience of their union embarking on industrial action since 1994. Of these, the mode had experience of solidarity action from fellow unions. This would strengthen the hands of workers engaging in collective action, and, through co-ordinating efforts, make union officials more aware of grassroots concerns (Kelly 1988, p. 170).

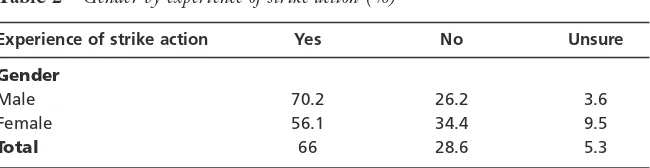

It is interesting to note that, while those with different skill and educational attainments were equally likely to strike, men were more prone to engage in collective action than women, as can be seen in Table 2.

This discrepancy may be partially explained by the fact that a large proportion of the female members of COSATU is concentrated in the South African Clothing and Textile Workers Unions (SACTWU).7The latter’s low strike profile repre-sents a combination of a long tradition of quiescent unionism,8ethnic and cultural divisions,9coupled with large scale down-scaling in that industry (and hence, fear of job losses) following the dropping of protective tariffs (c.f. Baskin 1991; Friedman 1987). However, a lower proclivity to strike could also reflect the tendency of women to be less active in union affairs.

Remoteness

In terms of the tripartite alliance with the ruling African Congress (ANC), COSATU is entitled to nominate 20 senior members to be placed in prominent positions on the ANC’s list of parliamentary candidates (South Africa’s electoral system is based on the principle of proportional representation). Drawing on the findings of the survey database, Wood and Psoulis (2001) found that COSATU members saw their parliamentary representatives as subject to the same rules of accountability and recall as their shopstewards. In short, while utility of the Alliance for COSATU may be contested (see Habib and Taylor 1999), it is evident that the rank and file do not see national leadership as being subject to different rules of accountability to those elected at local level; support remains contingent on delivery (Southall and Wood 1999).

Table 2 Gender by experience of strike action (%)

Experience of strike action Yes No Unsure

Gender

Male 70.2 26.2 3.6

Female 56.1 34.4 9.5

Total 66 28.6 5.3

It should be noted that a deeply embedded culture of non-collaboration forged in the liberation struggle persists. To many, the state is still a contested terrain, rather than a liberated zone. The same holds true for many other social institu-tions (c.f. Southall and Wood 1999; Habib and Taylor 1999; Barchiesi 1999). This militancy is a two-edged sword: it represents a powerful means of mobilisation, but makes it difficult for leadership to hold members to agreements reached, and for membership to accept the legitimacy of other interest groupings in society.

Checks on oligarchic tendencies at shopfloor level: Accountability and recall of shopstewards

As can be seen from Table 1, 97.5% of respondents had shopstewards at their workplace. There is little doubt that this office remains an important character-istic of union organisation in South Africa. More than one-third of respondents (35.9%) had personal experience of an errant shopsteward being relieved of their office. The most common reasons given were a perceived untrustworthiness of the incumbent, a failure to deliver on worker demands and/or an inability to effectively represent worker interests. Moreover, 92.7% of respondents reported that the shopstewards at their workplace were democratically elected by their constituents, most commonly by means of a secret ballot.10Again, there was generally a high degree of commonality in response to these questions, cutting across gender, age, skill and educational divides. However, female respondents were somewhat more uncertain of the method of election (Table 3), while a show

Table 3 Gender by method of electing shopstewards (%)

How were your shopstewards Show Secret Don’t know/ Total elected (if elected)? of hands ballot can’t remember

Gender

Male 42.3 53.6 4.1 100

Female 43.2 43.7 13.2 100

Total 42.6 50.6 6.8 100

Notes: All figures have been rounded off to the nearest 0.1.χ2= 18.867; d.f. = 2; s = 0.00; n= 634.

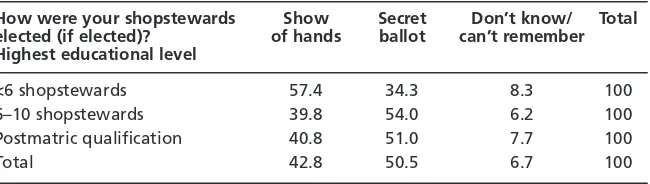

Table 4 Education by method of electing shopstewards (%)

How were your shopstewards Show Secret Don’t know/ Total elected (if elected)? of hands ballot can’t remember Highest educational level

<6 shopstewards 57.4 34.3 8.3 100

6–10 shopstewards 39.8 54.0 6.2 100

Postmatric qualification 40.8 51.0 7.7 100

Total 42.8 50.5 6.7 100

of hands was more commonly employed among less educated workers, reflecting literacy problems (Table 4).11

There is little doubt that a deeply entrenched internal culture of accountability and recall represents a powerful check on any oligarchic tendencies at workplace organisational level.

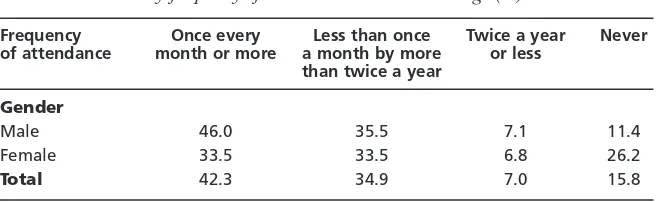

Escaping the Olsonian trap: Grassroots participation in union affairs

As can be seen in Table 5, the vast majority of COSATU members regularly participate in union affairs. Moreover, less skilled and less educated workers were just as likely to attend union meetings as their better educated peers.12In short, the unions have been able to secure enviable levels of participation at grassroots level; mass demobilisation has not taken place. However, the caveat mentioned earlier also holds; in a deeply divided society, it may be difficult to persuade the rank and file to accept the legitimacy of the state and other institutional configurations, democratisation notwithstanding.

Also of some concern is the fact that women remain less likely to participate than men. Meetings remain male-dominated affairs while a patriarchal organis-ational culture persists within many COSATU affiliates.13In addition, the ‘many incidents of sexual harassment of women comrades by male comrades . . . sexual exploitation taking place right within our own union structures’ would also deter women from attending union meetings (Transport and General Workers Union, quoted in Baskin 1991, p. 356). As a Chemical Workers Industrial Union official remarked: ‘These things are killing the struggle and women’s involvement in the union’ (Baskin 1991, p. 356). Moreover, a major barrier to female attendance at union meetings is housework. As Elizabeth Thabethe, a Chemical Workers Industrial Union official remarked: ‘To increase women’s participation in unions means changing the relationship between men and women. It needs men to share in domestic duties with women, and we have a long way to go before this happens’ (Baskin 1991, p. 374). Nonetheless, a sizeable number of female respondents continued to regularly attend union meetings.

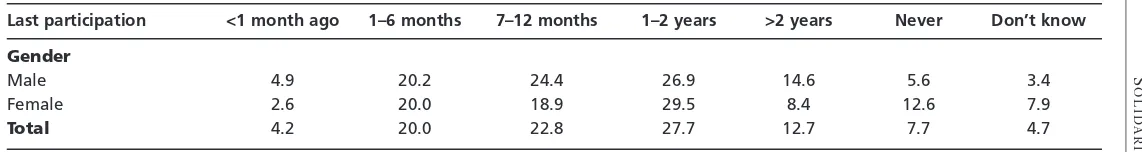

Again, women were somewhat less likely to have recently participated in elections for shopstewards, although, as can be seen in Table 6, the frequency of participation by both genders remains high.

Table 5 Gender by frequency of attendance at union meetings (%)

Frequency Once every Less than once Twice a year Never of attendance month or more a month by more or less

than twice a year

Gender

Male 46.0 35.5 7.1 11.4

Female 33.5 33.5 6.8 26.2

Total 42.3 34.9 7.0 15.8

S

OLIDARITY

,

R

EPRESENT

A

TIVITY

AND

A

CCOUNT

ABILITY

339

Last participation <1 month ago 1–6 months 7–12 months 1–2 years >2 years Never Don’t know

Gender

Male 4.9 20.2 24.4 26.9 14.6 5.6 3.4

Female 2.6 20.0 18.9 29.5 8.4 12.6 7.9

Total 4.2 20.0 22.8 27.7 12.7 7.7 4.7

Changes since 1994

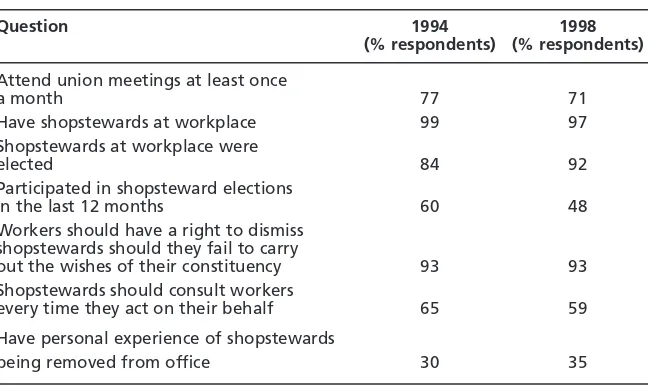

The survey represented a follow-up of one conducted in 1994 that employed similar methodologies (see Ginsburg et al.1995). An earlier survey of COSATU shopstewards was conducted in 1992 (as part of a broader study of media usage by union members) (Orkin and Pityana 1992). Both of these surveys found levels of shopfloor democracy and internal participation on a similar level to the 1998 one. Table 7 compares differences in responses to key questions between 1994 and 1998.

Most of the differences between the findings of the 1994 and 1998 surveys were so slight as to be possibly due to sampling differences. The somewhat higher proportion of elected shopstewards found in the 1998 survey would probably be a function of union maturity. Unions may appoint shopstewards in the initial organisational phases, then switch over to formal elections once a presence has been established (in the early 1990s, there was a wave of unionisation in the service sector). The slightly higher percentage of respondents who reported that they had personal experience of shopstewards being removed from office in 1998 could simply be due to the fact that independent unions had been around longer. However, it could also reflect an increasingly complex bargaining environment, with the battle lines being less clear-cut in the post-apartheid era. The more frequent shopsteward elections in the early 1990s are probably a product of the wave of union mergers that took place at that time, in many cases leading to a consolidation of shopfloor organisation between former rivals at workplaces.

CONCLUSION

The survey findings revealed the persistence of a culture of internal democracy and participation within the COSATU unions, doubtlessly contributing to the Table 7 Differences between the 1994 and 1998 surveys

Question 1994 1998

(% respondents) (% respondents)

Attend union meetings at least once

a month 77 71

Have shopstewards at workplace 99 97

Shopstewards at workplace were

elected 84 92

Participated in shopsteward elections

in the last 12 months 60 48

Workers should have a right to dismiss shopstewards should they fail to carry

out the wishes of their constituency 93 93

Shopstewards should consult workers

every time they act on their behalf 65 59

Have personal experience of shopstewards

continued high levels of union penetration in key sectors of South African industry in an age of union stagnation and decline (c.f. Kochan 2001, p. 1). More specifically, the survey revealed evidence of a culture of accountability and recall; members regularly removed ‘unresponsive’ shopstewards from office. Respondents had similar expectations from national leadership. In addition to vertical linkages, the survey revealed evidence of horizontal linkages between COSATU unions. Such linkages would draw officials closer to grassroots concerns (c.f. Kelly 1988), and be strengthened through shared experiences of racial discrimination, and space and place; almost a decade after democratisation, most South African workers continue to reside in crowded hostels and townships. Finally, while the survey revealed a high degree of social solidarity, important gender divisions persisted. Women were somewhat less likely to participate in union affairs (although still at a relatively high level). Moreover, a number of key COSATU affiliates faced membership drops in the 1990s, largely due to widespread redundancies in key areas of mining and manufacturing in response to heightened overseas competition. However, these losses have since been offset by impressive gains in the public sector, and through renewed member-ship drives in the private sector (Wood 2001). Indeed, the COSATU unions have seemingly managed to reconstitute much of the internal vigour of their youth, and represent an inspiring example for unions faced with the challenges of renewal worldwide.

ENDNOTES

1. Decentralised bargaining will, of course, have the immediate effect of further strengthening the position of existing shopsteward structures, and as such, is often favoured by shopstewards (Towers 1992, p. 167). However, an over-reliance on decentralisation proved disastrous to the British labour movement in the face of state and employer hostility by the early 1980s. Again, in South Africa, shopstewards have, in a number of notable cases, actively opposed centralised agreements at industry or firm-wide level. The wider institutional environment (other than in the economic sphere) remains relatively labour-friendly. However, the extent to which a vibrant shopfloor democracy may reduce the possibility of a broader social accord (going beyond the existing National Economic Development and Labour Advisory Council [NEDLAC], which has proved incapable of deflecting government from a neo-liberal policy trajectory), that would secure a national voice for organised labour over the medium term, remains uncertain.

2. An excellent overview of current challenges in South Africa’s industrial relations system can be found in Webster (1998).

3. The survey represented a follow-up of one conducted in 1994 (see Ginsburg et al.1995). An earlier survey of COSATU shopstewards was conducted (as part of a broader study of media usage by union members) (Orkin and Pityana 1992). Both these surveys found levels of shopfloor democracy and internal participation on a similar level to the 1998 one.

4. Telkom, the parastatal telecommunications company maintains up to date listings of businesses; listings that are available to researchers.

5. In both cases, bitter and protracted industrial disputes followed clashes between union leadership and ‘rebel’ shopstewards.

6. Africans residing in housing and flats in segregated residential areas. Up until the 1980s, Africans could only lease property in urban areas, and faced the omnipresent threat of forced removal as part of periodic government drives to reorder urban space.

7. Significant numbers can also be found in the National Education, Health and Allied Workers Union (NEHAWU), the South African Municipal Workers Union (SAMWU) and the South African Democratic Teachers Union (SADTU). However, the survey concentrated on COSATU’s members in the private sector.

9. SACTWU has a strong following among ethnic, coloured and Indian workers. These groups had more rights under apartheid than African workers, making it difficult to build an effec-tive non-racial union, a task made even harder by differences in home languages (Baskin 1991, p. 394).

10. A total of 92.7% of the 633 respondents who answered the question said that their shopstewards had been democratically elected by their constituents, the mode of the remainder (2.7%) being appointed by union officials (sometimes used as an interim measure when shopfloor organis-ation is still in its infancy). 50.6% of respondents said that their shopstewards had been elected by means of a secret ballot, 42.6% by means of a show of hands, and the rest were uncertain. 11. In South Africa, less than standard 6 level of education is often taken as a measure of

functional illiteracy.

12. The relationship between education and attendance at union meetings was not statistically significant (χ2= 4,016; d.f. = 2; s = 0675; n= 639). The relationship between skill level and attendance at union meetings was equally not statistically significant (χ2= 12.136; d.f. = 15; s = 0669; n= 639).

13. COSATU’s internal journal, The Shopsteward, regularly airs concerns of sexist behaviour within some COSATU unions.

REFERENCES

Barchiesi F (1999) COSATU and the first democratic government. Transformation38, 20–48. Baskin J (1991) Striking Back: A History of COSATU.Johanneburg: Ravan.

Batstone E, Boraston I, Frenkel S (1977) Shopstewards in Action.Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Bohmke H, Desai A (1996) Everything’s going wrong with Toyota. South African Labour Bulletin

20, 6.

Bonner P (1978) The decline and fall of the ICU: A case in self-destruction. In: Webster E, ed.,

Essays in South African Labour History. Johannesburg: Ravan.

Boraston I, Clegg H, Rimmer M (1975) Workplace and Unions.London: Heinemann. Crouch C (1982) The Logic of Collective Action.London: Fontana.

Feit E (1975) Workers Without Weapons. Hander: Archon.

Food and Canning Workers Union (1955) Letter from Head Office to Port Elizabeth Branch 25/1/55. Johannesburg.

Friedman S (1987) Building Tomorrow Today: African Workers in Trade Unions 1970–1984.

Johannesburg: Ravan.

Ginsburg D et al.(1995) Taking Democracy Seriously.Durban: IPSA. Government Gazette, (1995) Issue 16861. Pretoria: Government Printer.

Habib A, Taylor R (1999) Parliamentary opposition and democratic consolidation in South Africa.

Review of African Political Economy79, 109–15.

Hyman R (1992) Trade unions and the disaggregation of the working class. In: Regini M, ed.,

The Future of Labour Movements.London: Sage.

Kelly J (1988) Trade Unions and Socialist Politics.London: Verso.

Kelly J, Heery E (1994) Working for the Union.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kochan T (2001) Extended networks: A vision for next generation unions. Kochan T, Verna A,

eds, Proceedings of the International Conference on Union Growth.Toronto: Centre for Industrial Relations, University of Toronto.

Lambert R (1988) Political Unionism in South Africa: SACTU 1955-1965. Unpublished PhD thesis, Johannesburg: University of Witwatersrand.

Lewis, J (1984) Instrialisation and Trade Union Organization in South Africa, 1925-55.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Luckhardt K, Wall B (1980) Organize or Starve, the History of SACTU.London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Maree J (1987a) Overview: The emergence of the independent trade union movement. In: Maree J, ed., The Independent Trade Unions.Johannesburg: Ravan.

Maree J (1987b) SAAWU in the east London area. In: Maree J, ed., The Independent Trade Unions.

Johannesburg: Ravan.

Orkin M, Pityana S (1992) Beyond the Factory Floor: A Survey of COSATU Shop Stewards.

Johannesburg: Ravan.

Rogers J (1995) How divided progressives may unite. New Left Review210, 9.

Rogerson C (1991) Beyond racial fordism: Restructuring industry in the ‘New’ South Africa.

Tijdschrift voor Ekonimisches en Sociale Geografie82 (5), 352–66.

Southall R Wood G (1999) The congress of South African trade unions, the ANC and the election: Whither the alliance? Transformation38, 68–83.

Sutcliffe M, Wellings P (n.d.) Strike action in the South African manufacturing sector. The ShopstewardJohannesburg.

Towers B (1992) Collective bargaining levels. In: Towers B, ed, A Handbook of Industrial Relations: Practice and Law in the Employment Relationship.London: Kogan Page.

Von Holdt K (1991) The COSATU/ANC alliance. South African Labour Bulletin15 (8), 17–21. Weinbaum E (1999) Organizing labor. In: Nissen B, ed., Which Direction for Organized Labor?:

Essays on Organization, Outreach and Internal Transformation.Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Webster E (1987a) A Profile of Unregistered Union Members in Durban. In: Maree J, ed., The Independent Trade Unions. Johannesburg: Ravan.

Webster E (1987b) Introduction to labour section. In: Moss G, Obery I, eds, SA Review 4.

Johannesburg: SARS/Ravan.

Webster E (1998) The evolving labour relations system in South Africa: An overview.Paper presented at Industrial Relations Association of South Africa Annual Conference, Cape Town. Wood G, Mahabir P (2001) South Africa’s workplace forum system: A Stillborn experiment in the

democratization of work. Industrial Relations Journal32 (3), 230–43.

Wood G, Psoulis C (2001) Globalization, Democratization, and Organized Labor in Transitional Economies. Work and Occupations28 (3), 293–314.