A STUDY ON THE STRUCTURES AND FUNCTIONS

OF ENGLISH ADVERBIAL CLAUSES

IN THE ARTICLES ON TIME MAGAZINES

AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS

Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of

Sarjana Sastra

in English Letters

By

FRANSISKA DEWI HASTUTI

Student Number : 044214001

ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS

FACULTY OF LETTERS

SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY

i

A STUDY ON THE STRUCTURES AND FUNCTIONS

OF ENGLISH ADVERBIAL CLAUSES

IN THE ARTICLES ON TIME MAGAZINES

AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS

Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of

Sarjana Sastra

in English Letters

By

FRANSISKA DEWI HASTUTI

Student Number : 044214001

ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS

FACULTY OF LETTERS

SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY

ii

A

Sarjana Sastra

Undergraduate Thesis

A STUDY ON THE STRUCTURES AND FUNCTIONS

OF ENGLISH ADVERBIAL CLAUSES

IN THE ARTICLES ON TIME MAGAZINES

By

FRANSISKA DEWI HASTUTI

Student Number: 044214001

Approved by

Dra. Bernardine Ria Lestari, M. S.

August

11,

2009

Advisor

iii

A Sarjana Sastra Undergraduate Thesis

A STUDY ON THE STRUCTURES AND FUNCTIONS

OF ENGLISH ADVERBIAL CLAUSES

IN THE ARTICLES OF

TIME

MAGAZINES

By

FRANSISKA DEWI HASTUTI Student Number : 044214001

Defended before the Board of Examiners on August 22, 2009

and Declared Acceptable

BOARD OF EXAMINERS

Name Signature

Chairman :Dr. Fr. B. Alip, M. Pd., M. A. __________________ Secretary : Drs. Hirmawan Wijanarka, M. Hum. __________________ Member : Anna Fitriati, S.S., M. Hum. __________________ Member :Dra. Bernardine Ria Lestari, M. S. __________________ Member : Dr. Fr. B. Alip, M. Pd., M. A. __________________

Yogyakarta, August 31, 2009 Faculty of Letters Sanata Dharma University

Dean

iv

Be thankful for the difficult times.

During those times you grow.

Be thankful for your limitations.

Because they give you opportunities for improvement.

Be thankful for each new challenge.

Because it will build your strength and character.

Be thankful for your mistakes.

They will teach you valuable lessons.

v

I dedicate this thesis to:

Jesus Christ and Mother Mary

My beloved Mom and Dad

My lovely Sister and Brother

vi

LEMBAR PERNYATAAN PERSETUJUAN

PUBLIKASI KARYA ILMIAH UNTUK KEPENTINGAN

AKADEMIS

Yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini, saya mahasiswa Universitas Sanata Dharma:

Nama : Fransiska Dewi Hastuti

Nomor Mahasiswa : 044214001

Demi pengembangan ilmu pengetahuan, saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma karya ilmiah saya yang berjudul:

A STUDY ON THE STRUCTURES AND FUNCTIONS OF ENGLISH ADVERBIAL CLAUSES IN THE ARTICLES ON TIME MAGAZINES beserta perangkat yang diperlukan (bila ada). Dengan demikian saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma hak untuk menyimpan, mengalihkan dalam bentuk media lain, mengelolanya dalam bentuk pangkalan data, mendistribusikan secara terbatas, dan mempublikasikannya di Internet atau media lain untuk kepentingan akademis tanpa perlu meminta ijin dari saya maupun memberikan royalti kepada saya selama tetap mencantumkan nama saya sebagai penulis.

Demikian pernyataan ini yang saya buat dengan sebenarnya. Dibuat di Yogyakarta

Pada tanggal: 31 Agustus 2009

Yang menyatakan

vii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I have to thank so many people who have encouraged me with their love, prayer and support in the completion of writing this thesis. I could not manage my time well and I almost failed to fight against myself. I am very thankful to Jesus Christ and Mother Mary, who always bless my family and me in whatever condition we are. They also give me strength and patience in every second of my life. Thanks to Them, this thesis is finally done.

I am deeply indebted to Dra. Bernardine Ria Lestari, M. S., my advisor, who had patiently and wisely helped, guided, corrected and gave me invaluable suggestions for the completion of this thesis. I also would like to thank Dr. Fr. B. Alip, M. Pd., M. A., my co-advisor, for giving me suggestion and correction.

My deepest love and gratitude goes to my dearest father, Drs. A. B. Susiloputro, and my dearest mother, Agatha Maria, Amk, S. Pd, who always give me their endless love, care and patience. They are my best sponsors in life; without them, I am nobody. Thank you for giving me this opportunity to study in Yogyakarta, far from home. Also, I thank my sister Agnes “Eny” Purwanti and my brother Albertus “Wawan” Kurniawan. Thanks for your jokes and supports that always cheer me up. Dad, mom, Kak Eny and Wawan, thanks for giving me the best family I have ever had.

viii

Lisa, Clara, Windy, Siska, Dewi, Trisna, Ester, Ika), ex-Unit 3 (Kak Ari “Umi”, Kak Na, Anyesh, Agacil, Iin, Achonk, Etho, Bella, Galih, ZhaZha), Kak Wulan, Kak Ela, Mary “Doi Seng”, Gita, Laura, Elis Inang, Yu’ Yeni, Tela, and all Syantikers everywhere they are. Thanks for our precious and unforgettable moments. Caritas et Sapientia!

My gratitude is also aimed to all my lovely friends in English Letters 2004, especially Disty, Rani, Sheilla, Indri Nesta, Tini Smart, Dita Ndut, Nofee, Lutfi, Pita, Ella Moru, Elin, Amel, Astrid, Lisis, Ririn, Corry, Dede, Mas Jati, Bang Ison, Bang Veme, Bang Ucok, Soni, Six, Rizky, Nanang, “Didi” Reena Ray, Widi, Tata, crew of play performance ”In the Blood” (Donny and Fred), members of KKN Tangkilan XXXIV (Siska “Toa”, Ditha Kacamata, Mami Mpit, Fika, Stev “Bo Bo Ho”, Om Dito, Boris, Ci’ Fenny), and so on. Thanks for being my friends and introducing me the “flavor” of Java. Matur nuwun.

I give special thanks to all English Letters Teaching Staff for their guidance during my study here. I also send gratitude to all secretariat staff, especially mbak Nik, who have helped me with the administration matters. Big thanks also to all the library staff and ‘mitra’ in Sanata Dharma University Library. It is impossible to do this without their help.

Finally, many thanks are addressed to those who have given me a hand, whose names I cannot mention here one by one but I believe that God always blesses them all. Doumo arigatou gozaimasu…

ix

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE ... i

APPROVAL PAGE ………... ii

ACCEPTANCE PAGE ………. iii

MOTTO PAGE ……….. iv

DEDICATION PAGE ………... v

LEMBAR PERSETUJUAN PUBLIKASI KARYA ILMIAH ……… vi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ……….. viii

TABLE OF CONTENTS ……….. ix

LIST OF TABLE ……… xi

ABSTRACT ……… xii

ABSTRAK ……….. xiii

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION……… 1

A.

Background of the Study……….. 1

B.

Problem Formulation……… 4

C.

Objectives of the Study……… 5

D.

Definition of Terms……….. 5

CHAPTER II: THEORETICAL REVIEW………... 7

A.

Review of Related Studies……… 7

B.

Review of Related Theories……….. 9

1.

Definition of Adverbial Clauses ………. 9

2.

Subordinating Conjunction of Adverbial Clauses………... 10

3.

Structural Types of Adverbial Clauses……… 12

a.

Finite Adverbial Clauses……… 12

b.

Non-Finite Adverbial Clauses………14

c.

Verbless Clauses……… 16

4.

Semantic Functions of Adverbial Clauses………... 17

a.

Adverbial Clauses of Time……… 17

b.

Adverbial Clauses of Place……….... 19

c.

Adverbial Clauses of Cause/Reason……….. 20

d.

Adverbial Clauses of Result……….. 22

e.

Adverbial Clauses of Purpose……… 23

f.

Adverbial Clauses of Contrast………... 24

g.

Adverbial Clauses of Manner……… 27

h.

Adverbial Clauses of Condition ……… 28

i.

Adverbial Clauses of Degree………. 31

5.

The Position and Punctuation of Adverbial Clauses………32

x

CHAPTER III: METHODOLOGY………….………..….. 35

A.

Object of the Study………..………. 35

B.

Method of the Study………..………... 35

1.

Kind of Research………..35

2.

Data Collection………...………. 36

3.

Data Analysis………..……… 37

CHAPTER IV: ANALYSIS……….. 38

A.

The Functions of the Adverbial Clauses……… 38

1.

Adverbial Clauses of Time……….. 39

2.

Adverbial Clauses of Place………... 43

3.

Adverbial Clauses of Cause/Reason……… 44

4.

Adverbial Clauses of Result……… 46

5.

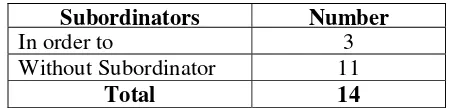

Adverbial Clauses of Purpose……….. 47

6.

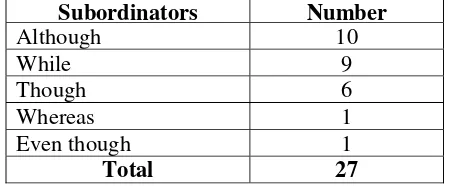

Adverbial Clauses of Contrast………... 49

7.

Adverbial Clauses of Manner……….. 51

8.

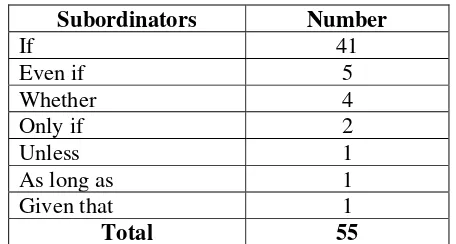

Adverbial Clauses of Condition ……….. 52

9.

Adverbial Clauses of Degree………...…… 54

B.

The Structure of the Adverbial Clauses………. 56

1.

Finite Adverbial Clauses……….. 57

2.

Non-Finite Adverbial Clauses ……….59

a.

Infinitive Clauses ……….. 60

b.

–ed

Clauses ………62

c.

–ing C

lauses………... 64

3.

Verbless Adverbial Clauses ……… 67

4.

The Position and Punctuation of the Adverbial Clauses………. 69

CHAPTER V: CONCLUSION……….75

BIBLIOGRAPHY……….. 78

xi

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. The Functions of Adverbial Clauses Found in the Articles of Time

Magazines published on May 26 and June 2, 2008 ……… 39

Table 2. Subordinators of Adverbial Clause of Time ………. 40

Table 3. Subordinators of Adverbial Clause of Cause/Reason ……… 44

Table 4. Subordinators of Adverbial Clause of Purpose……….. 48

Table 5. Subordinators of Adverbial Clause of Contrast ……….49

Table 6. Subordinators of Adverbial Clause of Condition ……….. 52

Table 7. The Structural Types of Adverbial Clauses found in the Articles on Time Magazines………..……… 56

Table 8. Numbers of Non-Finite Adverbial Clauses……… 59

xii

ABSTRACT

FRANSISKA DEWI HASTUTI (2009). A Study on the Structures and Functions of Adverbial Clauses in the Articles on Time Magazines. Yogyakarta: Department of English Letters, Faculty of Letters, Sanata Dharma University.

Complex sentence is frequently used to combine two or more simple sentences of different levels in order to make an effective writing. It consists of a main clause and one or more subordinate clauses. One of the commonest subordinate clauses used in writing is adverbial clause. Adverbial clause is a clause functions as an adverb, mainly as an adjunct or a disjunct. Therefore, it describes a verb, an adjective or the other adverb. Since adverbial clause has the most subordinating conjunctions, which enables us to arrange numerous sentences, there can be sentences of great complexity that may cause ambiguity and misunderstanding. Therefore, this thesis is meant to analyze the structures and the functions of the adverbial clause in several articles on Time Magazines.

This thesis has two objectives. First, to find out the functions of the adverbial clauses mostly used in the articles on Time magazines. After finding out the functions of the adverbial clauses, then, the second objective is to find out the structures of each function of adverbial clauses in the articles on Time magazines.

xiii ABSTRAK

FRANSISKA DEWI HASTUTI (2009). A Study on the Structures and Functions of Adverbial Clauses in the Articles on Time Magazines. Yogyakarta: Jurusan Sastra Inggris, Fakultas Sastra, Universitas Sanata Dharma.

Kalimat majemuk sering digunakan untuk menggabungkan dua atau lebih kalimat sederhana yang berbeda tingkatan agar membuat tulisan menjadi efektif. Kalimat majemuk terdiri dari sebuah klausa utama dan satu atau lebih klausa bawahan. Salah satu klausa bawahan yang paling sering digunakan dalam tulisan adalah klausa keterangan. Klausa keterangan adalah klausa yang berfungsi sebagai keterangan, terutama sebagai adjunct dan disjunct. Oleh karena itu, klausa ini menjelaskan kata kerja, kata sifat, dan kata keterangan lainnya. Karena klausa keterangan memiliki kata hubung antarklausa yang paling banyak yang memudahkan kita untuk membuat beragam kalimat, akan timbul kalimat-kalimat yang sangat kompleks yang dapat menyebabkan ambigu dan kesalahpahaman. Maka, tesis ini disusun untuk menganalisa struktur dan fungsi klausa keterangan pada beberapa artikel pada Majalah Time.

Tesis ini memiliki dua tujuan. Pertama, untuk menemukan fungsi klausa keterangan yang paling sering digunakan pada artikel Majalah Time. Kemudian tujuan kedua adalah untuk menemukan struktur dari setiap fungsi klausa keterangan tersebut.

Dalam menganalisa permasalahan di atas, peneliti menerapkan metode penelitian empiris. Pertama, data dikumpulkan dan dikelompokkan menjadi beberapa fungsi. Kemudian peneliti menganalisa struktur dari data yang telah dikumpulkan. Peneliti juga menerapkan studi kepustakaan untuk memperoleh teori-teori dan informasi.

xiv

1

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

A.

Background of the Study

Human beings are not only individual creature but also social creature. As

social creature, they need to communicate and interact with other people. Without

communication, people will not be able to do their daily activities easily in their

life. Hence, we need a language as the crucial vehicle of all human knowledge. “It

is the basic foundation of all human cooperation, without which no civilization is

possible” (Pei, 1984: 210).

By using the language, we are able to express our ideas, opinions and

feelings such as love, hate, evil, sympathy and so on. We can also use language to

transmit information to others, either in spoken or in written form. The spoken

form is related to the use of sound. It can be spoken directly like when two people

or more are in conversation, or recorded mechanically like when a newscaster is

reading news on television. The written form can be found in any kind of printed

media such as literary text, schoolbooks, newspaper, magazine, journal and so on.

To use a language well and to make other people comprehend what we are

talking or writing about, we need to know the grammar of a language. Radford

states that

2

principles which specify how to form, pronounce, and interpret Phrases

and Sentences in the language concerned” (Radford, 1988: 2).

It means that grammar provides the learners with a set of rules or principles

applied in every English sentence from the very simple sentence up to the

complex sentence.

In simple sentences, there is only one clause. According to Quirk et al.

(1972: 342), a

clause

is a unit that can be analyzed into the elements Subject,

Verb, Complement, Object, and Adverbial. Therefore, a simple sentence contains

only one subject and one verb phrase, and may have an object or a complement

and one or more adverbials as well.

Using only simple and short sentences, we will not be able to explain what

we intend to say completely. Besides, a series of simple and short sentences in

explaining something can make our writings become not efficient. Therefore, we

can combine simple sentences with other simple sentences to form compound

sentences, complex sentences or even compound-complex sentence. For example,

the simple sentence

Lisa sings on the stage

can be combined with the simple

sentence

John accompanies her on the piano

to form the compound sentence

Lisa

sings on the stage

and

John accompanies her on the piano.

In a compound

sentence, all the simple sentences have grammatically equal importance to one

another and they are combined with a coordinating conjunction such as

and, or

and

but

.

Different from a compound sentence, in a complex sentence there is more

3

is a sentence consisting of only one main clause and one or more subordinate

clause functioning as element of the sentence. The main clause is an independent

clause since it can constitute a simple sentence and the subordinate clause is a

dependent clause because it makes up a grammatical sentence only if subordinate

to a further clause (1972: 720-721).

Furthermore, Greenbaum and Quirk (1997: 304-305) distinguish four

major categories of subordinate clauses based on their potential functions. They

are nominal clauses, relative clauses, adverbial clauses and comparative clauses.

A nominal or noun clause is a clause which has a function like a noun phrase or a

pronoun, such as subject, object, complement, appositive, or prepositional

complement. For example, in the sentence

That we need a larger computer has

become obvious,

the nominal clause

that we need a larger computer

functions as

the subject of the sentence

.

A relative or adjective clause does the work of an

adjective in modifying the noun phrase or a pronoun. It provides extra information

about the noun it follows. For example,

The girl who wears glasses is my sister.

The adjective clause

who wears

glasses modifies the noun phrase

the girl.

Meanwhile, adverbial clause is a clause functions as an adverb, mainly as an

adjunct or a disjunct. Therefore, it describes a verb, an adjective or the other

4

modifying functions. It is equivalent to degree adverb. For example,

She has more

patience than you have.

Among four major categories of subordinate clauses above, an adverbial

clause has the most subordinating conjunctions, which enables us to arrange

numerous clause structures. As the result, there can be sentences of great

complexity that may cause ambiguity and misunderstanding. Kolln (1990: 360)

states that the long list of subordinators, which enables us to connect ideas for a

wide variety of reasons, may often show up problems related to the meaning of

the sentence: the wrong idea gets subordinated and the meaning of the

subordinator is imprecise. We still can find those problems in many kinds of

writings including the published articles that many people read.

In this thesis, the writer conducted a study on English adverbial clauses

used in several articles on

Time

magazines published on May 26 and June 2, 2008.

The study focuses on the structures and the functions of the adverbial clause as

subordinate clause in a complex sentence in order that the reader may get better

understanding on adverbial clauses and use the subordinators precisely in the

complex sentence.

B.

Problem Formulation

Based on the explanation affirmed earlier, these are some questions I

would like to discuss as the main way for the next analysis on this paper. The

questions to gain a comprehensive understanding on the title of this paper can be

5

1.

What are the functions of adverbial clauses mostly used in the articles on

Time

magazines published on May 26 and June 2, 2008?

2.

How are every function of adverbial clauses constructed in the articles on

Time

magazines published on May 26 and June 2, 2008?

C.

Objectives of the Study

Having problem formulations above, this thesis has some objectives, they

are: first, to find out the functions of the adverbial clauses mostly used in the

articles on

Time

magazines. By knowing the functions of the adverbial clauses, we

can find the precise subordinators that introduce the adverbial clauses. After

finding out the functions of the adverbial clauses, then, the second objective is to

find out the structures of each function of adverbial clauses in the articles on

Time

magazines.

D.

Definition of Terms

This is a study conducted to analyze the structures and the functions of

adverbial clauses. Therefore, we need to define the terms structures, functions and

adverbial clauses into a more specific linguistic definition.

1.

Structure

In

Webster’s Encyclopedic Unabridged Dictionary of the English

Language,

structure is defined as “a complex system considered from the point of

view of the whole rather than of any single part” (Webster, 1989: 1410).

6

viewed as a system in which the elements are defined in terms of relationship to

other elements” (Pei, 1966: 262).

Therefore, the term structure used in this thesis refers to the regularities

and patterns of a complex system as a whole unity in relationship to other

elements. It categorizes the adverbial clauses syntactically into finite adverbial

clauses, non-finite adverbial clauses, verbless adverbial clauses, and also the

position and the punctuation of the adverbial clauses.

2.

Function

The writer uses the term function to refer to the semantic function

according to Greenbaum and Quirk’s

A Student’s Grammar of the English

Language.

Greenbaum and Quirk say that the semantic function of adverbial

clause is the meaning of adverbial clause in relation to the main clause (1997:

314). Therefore, it categorizes the meaning of adverbial clauses into several types:

adverbial clauses of time, adverbial clauses of place, adverbial clauses of contrast,

etc.

3.

Adverbial Clause

As the name indicates, an adverbial clause is a dependent clause that

replaces the position of an adverb in a simple sentence. It functions mainly as an

adjunct or a disjunct (Quirk et al., 1972: 743). It modifies a verb, an adjective, or

an adverb, and is introduced by subordinating conjunctions to express the relation

7

CHAPTER II

THEORETICAL REVIEW

Chapter II contains three parts. The first part, Review of Related Studies,

will reveal the studies conducted by two scholars about the similar object, in this

case adverbial clauses. To support the topic, some theories that are going to be

applied will be presented in the second part, Review of Related Theories. These

theories are provided for the analysis. They concern about the structures of

adverbial clauses as well as the functions of adverbial clauses. The last part is

Theoretical Framework. This part will cover the important review of related

theories in answering the problem formulations. This thesis discusses about the

analysis of adverbial clauses in the articles on

Time

magazines.

A.

Review of Related Studies

Many scholars have conducted a study on adverbial clauses. For example,

Wisnu Widya Tama analyzed parts of adverbial clauses in his thesis entitled “A

Study of the Construction of English Cause and Reason Clauses” in

Time Asia

magazines published on September 30, October 07, 14 and 21, 2002. The

problems discussed are: the forms used to construct English cause and reason

clauses and the distribution of the forms. He used library research method as the

method of the study. In doing his analysis, Wisnu used data collection and data

8

For the first problem, he subsequently concluded that the statement of English

cause and reason could occur in independent clauses, dependent clauses with

subordinators or transitions, and verbless and non-finite dependent clauses. For

the second problem, he concluded that a clause with a specific conjunction can

have position in the beginning, middle or at the end of complex sentence, whereas

some clauses introduced by some conjunctions are seemingly placed in a fixed

distribution.

Similar to Wisnu, Pia Yongkik Suprihatin also discussed about part of

adverbial clause in her thesis entitled “The Frequency of

so…that, such…that,

…enough to infinitive, too…to infinitive

Adverbial Clauses of Result used by

Native Writers”

.

In composing her thesis, she collected the data from the samples

of five books of science, three books of literature, and four magazines. Pia was

trying to explore the frequency of

so…that, such…that, …enough to infinitive,

and

too…to infinitive

adverbial clauses of result. The research was also intended to

classify

so…that, such…that, …enough to infinitive,

and

too…to infinitive

adverbial clauses of result whether they belong to the high, medium or low

frequency level.

This current study is similar to both previous studies above since it also

discusses adverbial clauses. However, unlike those previous studies that

investigate only one or two parts of adverbial clauses, this thesis will analyze the

adverbial clauses deeply and completely. This will include all the syntactic and

9

B. Review of Related Theories

In this part, the writer includes several theories from some linguists to analyze the object of the study in order to give limitation and help the writer to process the data and draw them into conclusion.

1. Definition of Adverbial Clauses

According to John E. Warriner in his book English Grammar and Composition, adverbial clause can be defined as follows:

An adverb clause is a subordinate clause that, like an adverb, modifies a verb, an adjective, or an adverb. Adverb clauses often begin with a word like after, because, or when that expresses the relation between the clause and the rest of the sentence (1982: 62).

According to Quirk et al. in their book A Grammar of Contemporary English, adverbial clauses are “clauses serving primarily as adjuncts or disjuncts in the main clause and may be placed in various semantic categories, such as time, place, and manner” (1972: 743). They also add that adjuncts are integrated within the structure of the clause to at least some extent. For example, the adverbial clause in He writes to his parents because he wants to is an adjunct. On the other hand, disjuncts are peripheral to clause structure (Quirk et al., 1972: 421). As a disjunct, usually the adverbial clause is separated by a comma from its main clause. Textually, disjuncts represent a comment by the writer on the content of the clause as a whole (Downing and Locke, 2003: 62). For example, He is drunk, because I saw him staggering. In this sentence there is an implication that might

10

respect to the form of the communication or to its content (Quirk and Greenbaum, 1973: 26). The other example is To be honest, I do not like him. The adverbial clause to be honest is a disjunct which is simply a comment. Therefore, it is separated by a comma from its main clause.

Based on the definition given by two linguists above, we can define that an adverbial clause is a dependent clause that functions mainly as an adjunct or disjunct and modifies a verb, an adjective, or an adverb, and is introduced by subordinating conjunctions to express the relation between the clause and the rest of the sentence.

2. Subordinating Conjunction of Adverbial Clauses

Subordinating conjunction, or subordinator, is one of the important elements in complex sentence, especially in the subordinate clauses. Frank states that subordinating conjunction introduces a clause that depends on a main or independent clause. It is grammatically part of the clause it introduces; it is never separated from its clause by comma (1972: 206).

11

semantic relation between the subordinate clause and the unit within which it is embedded.

Quirk et al. (1972: 727-728) divides subordinating conjunctions into three main categories:

i Simple Subordinators

A simple subordinator contains only a single word. The subordinators belong to this category are: after, (al)though, as, because, before, since, if, how(ever), once, unless, until, when(ever), where(ver), whereas, whereby, while.

ii Compound Subordinators

A compound subordinator consists of two or more words:

- ending with that: in that, so that, in order that, such that, except that - ending with optional that: now (that), providing (that), provided (that),

supposing (that), considering (that), given (that), granting (that),

granted (that), admitting (that), assuming (that), presuming (that),

seeing (that), immediately (that), directly (that)

- ending with as: as for as, as long as, so long as, insofar as, so far as,

inasmuch as, according as, so as (+ to + infinitive)

- ending with than: sooner than (+ infinitive), rather than (+ infinitive) - other: as if, as though, in case

iii Correlative Subordinators

12

if…then, as…so, more/-er/less…than, as…as, so…(that), such…as, no sooner…

than, whether…or, the…the.

Some of these subordinators may be preceded by intensifiers such as just because, only when, right after; or by negatives such as not because, never because. In relation to the meaning of the subordinators, Jackson adds that some subordinators are used with more than one type of adverbial meaning: since may indicate ‘time’ or ‘reason’ and so that may indicate ‘purpose’ or ‘result’ (Jackson, 1990: 214). Therefore, context is necessary to give contribution to the meaning of the adverbial clauses. For example, the subordinator since that is used to introduce the adverbial clause in sentence I have played tennis since I was a young girl indicates the time of the main clause. Meanwhile, since in the sentence Since the weather has improved, the game will be held as planned is used to indicate the

reason for the main clause.

3. Structural Types of Adverbial Clauses

The structural type of the adverbial clauses focuses on the element they contain, such as the verb. Therefore, adverbial clauses syntactically can be divided into finite adverbial clauses, non-finite adverbial clauses and verbless clauses.

a. Finite Adverbial Clauses

13

Finite clause is a clause containing a finite verb. It always contains a subject as well as a predicate, except in the case of commands (Quirk et al., 1972: 722). In finite adverbial clause, the verb is able to show grammatical properties such as tense (past or present), person (first person, second person or third person) and number (singular or plural).

(1) Bill did not come to the meeting because he got an accident.

Sentence (1) contains an independent clause Bill did not come to the meeting and a dependent clause because he got an accident, which contains a finite verb got. Since the adverbial clause because he got an accident indicates the past tense, as the main clause does, so the form of the finite verb get changes into the past tense got.

Furthermore, Quirk et al. state that in adverbial finite clauses, the whole of the predication or part of it can be omitted, except that we cannot ellipt merely the object (1972: 538). Part of adverbial finite clauses that can be omitted are:

a). Whole of Predication

(2) John will play the guitar if Tom will (play the guitar).

(3) Because Alice won’t (dust the furniture), Mary is dusting the furniture. b). Subject Complement Only

(4) I’m happy if you are (happy).

(5) You must be the member of the party, since he is (a member of the party). but not if the verb in the subordinate clause is other than BE:

14

c). Adjunct Only

(7) Tom was at Oxford when his brother was (at Oxford).

(8) I’ll write to the committee if you’ll write (to the committee) too. d). Lexical Verb Only

(9) John is playing Peter though Tom won’t (play) Paul. (10) I’ll pay for the hotel if you will (pay) for the food. but not

e). Object Only

(11) *He took the money because she wouldn’t take (the money). (12) *I’ll open an account if you’ll open (an account).

(Quirk et al., 1972: 538-539) An object cannot be ellipted in finite clause since the predication consists of the transitive verb which requires an object. If the object is ellipted, the meaning of the sentence will be suspended and incomplete.

b. Non-Finite Adverbial Clauses

Different from finite clause, a non-finite clause contains a non-finite verb. Thus, the verb in a non-finite adverbial clause does not show a contrast in tense between past or present and cannot be marked for person and number.

15

because they are explicitly bound to the main clause syntactically. When the subject is not present in a non-finite or verbless clause, it is assumed to be identical in reference to the subject of the main clause. This term used to identify the subject is called the attachment rule.

The classes of non-finite adverbial clause and their examples are: a) Infinitive

Most of adverbial infinitive clauses contain to, except when introduced by rather than and sooner than. Besides, in those of the first type, the subject of the

infinitive is preceded by for, as shown in (14).

(13) Rather than study, Sam watched the football game. (without to) (14) The best thing would be for you to tell everybody. (with subject)

(15) He shook his head as if to signal his approval. (with subordinator and without subject)

(16) To type the letter accurately, he worked hard. (without subject) b) -ing participle

(17) Leaving the room, he tripped over the mat. (without subject) (18) The letters having been written, he went home. (with subject)

(19) When speaking English, Peter often makes mistakes. (with subordinator) c) -ed participle

(20) Covered with confusion, I left the room. (without subject) (21) The job finished, we left the room and went home. (with subject)

(22) Unless kept to a minimum, footnotes will put the reader off. (with subordinator)

16

Sometimes the attachment rule is violated. The violation can cause a dangling clause or modifier. According to Greenbaum (1989: 240), a dangling modifier does not have its own subject, and its implied subject cannot be identified to be identical in reference with the subject of the main clause, although it can usually be identical with some other reference in the main clause. For example:

Dangling: Although large enough, they did not like the apartment. Correct: Although the apartment was large enough, they did not like it.

Greenbaum and Quirk (1997: 328) also add that the attachment rule does not apply if the implied subject of the adverbial clause is the whole of the main clause. In example I will help you if necessary, the subject of the if-clause is not I but the whole sentence. Thus, if the subject is present, it should be I will help you if it is necessary.

c. Verbless Clauses

Leech and Svartvik (1994: 250) state that verbless clauses do not contain verb element and often without subject. However, they are regarded as clauses because they function like finite and non-finite clause, and because they can be analyzed in terms of one or more clause elements. The subject, when omitted, can usually be understood as equivalent to the subject of the main clause. The attachment rule in verbless clause is so much the same as in non-finite clause. The examples of verbless clause are:

17

(25) A sleeping bag under each arm, they tramped off on their vacation. (26) The oranges, when ripe, are picked and sorted.

(27) Whether right or wrong, Michael always comes off worst in an argument. In (23) and (24), the verbless clauses have explicit subjects. Verbless adverbial clauses may be preceded by subordinating conjunctions like sentence (26) and (27) or without the subordinators like in (23) - (25).

In verbless adverbial clauses, when the subject and the be-form are omitted, the retained portion of the predicate may be: a predicate noun, a predicate adjective, a prepositional phrase, a present participle, a past participle or an infinitive. The examples of each the retained portion of the predicate can be seen in the following explanation discussing about the functions of adverbial clauses.

4. Functions of Adverbial Clauses

Greenbaum and Quirk states that semantic analysis of adverbial clauses is complicated by the fact that many subordinators introduce clauses with different meanings: for example a since-clause may be temporal or clausal (1997: 314). Here, the writer will show the semantic functions of adverbial clauses classified based on the meaning of the subordinators in the clauses. The following theories are mostly taken from Greenbaum and Quirk’s A Student’s Grammar of the English Language and Frank’s Modern English: A Practical Reference Guide.

a. Adverbial Clauses of Time

18

clause may be previous to that of the adverbial clause (until), simultaneous with it (while), or subsequent to it (after). The time relationship may also convey duration (as long as), recurrence (whenever), and relative proximity (just after).

As a clause denoting time, adverbial clauses of time are introduced by some subordinating conjunctions such as when, while, since, since, before, after, until, as, as soon as, now (that) and once. The uses of the subordinators in the

sentences can be seen from the examples below: (28) You may begin WHEN(EVER) you are ready. (29) WHILE he was walking home, he saw an accident.

(30) They have become very snobbish SINCE they moved into their expensive apartment.

(31) Shut all the windows BEFORE you go out.

(32) AFTER she finished dinner, she went right to the bed.

(33) UNTIL Mr. Lee got a promotion in our company, I’d never noticed him. (34) We’ll do nothing further in the matter TILL we hear from you.

(35) AS he was walking in the park, he noticed a very pretty girl. (36) I’ll go to the post office AS SOON AS I wrap this package. (37) You may keep my book AS LONG AS you need it.

(38) NOW (THAT) the time has arrived for his vacation, he doesn’t want to leave.

(39) ONCE she makes up her mind, she never changes it.

19

clause beginning with only or not requires a reversal of subject and verb in the main clause (Frank, 1972: 236). For example:

(40) NOT UNTIL (ONLY WHEN) the plane landed did she feel secure.

The verbless clause of time may have several forms by omitting the subject and a form of be-from the clause. The examples of verbless clauses of time are:

(41) When (I was) a boy, I went to the lake every summer. (42) When (we are) young, we are full of hopes and anxieties. (43) When (you are) in the army, you must obey all commands. (44) She turns on the radio when (she is) doing the housework.

(45) War, when (it is) waged for a long time, can destroy the morale of a country.

(Frank, 1972: 239) The retained portion of the predicate may be a predicate noun [as in (41)], predicate adjective [as in (42)], prepositional phrase [as in (43)], present participle [as in (44)] or past participle [as in (45)]. From the examples above, the subjects of the main clauses also serve the subjects of the verbless clauses.

b. Adverbial Clauses of Place

20

Furthermore, Greenbaum and Quirk (1997: 315) write that adverbial clauses of place may indicate position (46) or direction (47).

(46) WHERE the fire had been, we saw nothing but blackened ruins. (47) They went WHEREVER they could find work.

According to Frank (1972: 240), a conjunction of place may consist of an adverbial compound ending in –where or –place, with or without that following it such as anywhere (that), nowhere (that) everywhere (that), any place (that), no place (that), and every place (that).

The omission of subject and be-form in verbless clause of place may cause the retained portion of predicate in the forms of a predicate adjective [as in (48)] and a past participle [as in (49)].

(48) Repairs will be met wherever (they are) necessary. (49) We will work wherever (he is) sent by his company.

c. Adverbial Clauses of Cause/Reason

This type of adverbial clause shows the cause or reason why something happened or was done. Greenbaum and Quirk (1997: 322) state that reason clauses convey a direct relationship with the main clause. The relationship may be that of cause and effect, as in (50); reason and consequence, as in (51); motivation and result, as in (52); or circumstances and consequence, as in (53). The examples can be seen as follows:

21

(53) Since the weather has improved, the game will be held as planned. Because may be preceded by intensifiers only and just, as in (52). Because

and since are the most commonly subordinators that indicate cause or reason. Other subordinators introducing the cause/reason clauses are:

(54) AS he was in hurry, he hailed the nearest cab.

(55) NOW (THAT) he’s inherited his father’s money, he doesn’t have to work anymore.

(56) WHEREAS a number of the conditions in the contrast have not been met, our company has decided to cancel the contract.

(57) INASMUCH AS every effort is being made to improve the financial condition of this company, the term of the loan will be extended.

(58) AS LONG AS it’s raining, I won’t go out tonight.

(59) His application for the job was rejected ON THE GROUND THAT he had falsified some of the information.

(Frank, 1972: 246) As long as is a synonym for since, but not for because. It is a more casual conjunction, often suggesting the feeling of anyhow.

Frank (1972: 248) states that the subject and a form of be may be omitted from a clause of cause. The retained portion of the predicate may be a predicate adjective and a participle, as in (60) and (61).

(60) Her nasty remarks are all the more insulting since (they are) intentional. (61) Since (it was) agreed on by the majority, this measure will be carried

22

d. Adverbial Clauses of Result

Adverbial clauses of result give the consequences of an action or event in the main clause. The subordinators introducing adverbial clauses of result are so (that), so … that, such (a) … that, with the result that. For example :

(62) We paid him immediately, SO (THAT) he left contented. (63) I took no notice of him, SO (THAT) he flew into a rage. (64) She is SO emotional THAT every little things upset her.

(65) She behaved SO emotionally THAT we knew something terrible had upset her.

(66) This is SUCH an ugly chair THAT I am going to give it away. (67) These are SUCH ugly chairs THAT I am going to give them away. (68) This is SUCH ugly furniture THAT I am going to give them away.

(Frank, 1972: 249) The sentences number (64) – (68) are the examples of the subordinators of adverbial clauses of result with insertion. So … that is inserted by an adjective

emotional in sentence (64) and an adverb emotionally in sentence (65).

Meanwhile, such … that may be inserted by singular countable noun in (66), plural countable noun in (67) or uncountable noun in (68).

Frank (1972: 250) adds that sometimes so that is separated in such a way that so begins the main clause; in these cases a reversal of word order in the main clause is required.

(69)So powerful was he that none dared resist him.

23

e. Adverbial Clauses of Purpose

Adverbial clauses of purpose show the purpose behind an action in the main clause. They are mostly introduced by the subordinators (in order) to and (so as) to. Thus, purpose clauses are usually infinitival. In (72), the subject is

preceded by for and inserted between in order and to.

(70) Students should take notes (SO AS) TO make revision easier.

(71) The committee agreed to adjourn (IN ORDER) TO reconsider the matter when fuller information became available.

(72) They left the door open (IN ORDER) for me TO hear the baby.

(Greenbaum and Quirk, 1997: 323)

Finite clauses of purpose are introduced by so that or by so, and by in order that. For example :

(73) The school closes earlier SO (THAT) the children can get home before dark.

(74) The jury and the witnesses were removed from the court IN ORDER THAT they might not hear the arguments of the lawyers on the

prosecution’s motion for an adjournment.

(Greenbaum and Quirk, 1997: 323) Frank (1972: 252) says that a purpose clause, especially introduced by so (that) often resembles a clause of result. However, certain physical features

24

writing. The difference can be seen in the examples below, where (75) is clause of purpose and (76) is clause of result:

(75) He is sitting in the front row so (that) he may hear every word of the lecture.

(76) He sat in the front row, so (that) he heard every word of the lecture.

f. Adverbial Clauses of Contrast

According to Marcella Frank, there are two types of the adverbial clauses of contrast: concessive and adversative. The concessive clause offers a partial contrast. It states a reservation that does not invalidate the truth of the main clause. The adversative clause makes a stronger contrast that may range all the way to complete opposition (Frank, 1972: 241).

The difference between concessive clauses and adversative clauses can be seen in the explanation as follows:

1) Concessive Clauses

According to Greenbaum and Quirk (1997: 320), concessive clauses indicate that the situation in the main clause is contrary to what one might expect in view of the situation in the concessive clause.

The subordinators commonly used to introduce concessive clauses are although, though and even though. Frank states that these three subordinators

have practically the same meaning. Yet, though is less informal than although and even though adds the most force to the concession (Frank, 1972: 241).

25

(79) EVEN THOUGH she disliked the movies, she went with her husband to please him.

(80a) WHILE admitted stealing the money, he denied doing any harm to the owner.

(80b) WHILE he denied doing any harm to the owner, he admitted stealing the money.

(81) EVEN IF he’s unreliable at times, he’s still the best man for the job. Frank (1972: 241-242) adds that while is also frequently used as a concessive subordinator as in (80), especially in informal English. Concessive clause introduced by while is likely to be reversible as shown in sentence (80a) as the reversed version of sentence (80b). In concessive clause introduced by even if, a concessive meaning may merge with the conditional meaning as shown in (81).

In formal English, certain participles combining with that function as conjunctions of concession.

(82) GRANTED (THAT) he has always provided for his children, still he has never given them any real affection.

(83) CONCEDED THAT his ceremony is unimpeachable, still it might be merely circumstantial evidence.

(84) ADMITTED THAT what you say is true, still there is much to be said for the other side.

26

2) Adversative Clauses

Adversative subordinators often set up a complete contrast:

(85) WHILE Robert is with everyone, his brother makes very few friends. (86) WHERE the former governor had tried to get cooperation of the local

chiefs, the new governor aroused their hostility by his disregard for their

opinions.

(87) Soccer is a popular spectator sport in England, WHEREAS in United States it is football that attracts large audiences.

(88) He claims to be a member of the royal family WHEN in fact his family were immigrants.

(Frank, 1972: 244) The subject and be-form can be omitted from a clause of contrast. The retained portion of the predicate may be a predicate noun [as in (89)], a predicate adjective [as in (90)], a prepositional phrase [as in (91) and (92)], a present participle [as in (93)], or a past participle [as in (94)].

(89) Although (he is) only a child, he works as hard as adult. (90) Although (he is) very young, he works as hard as adult.

(91) Although (he was) in a hurry, he stopped to help the blind man cross the street.

(92) I’ll come and visit you soon, if (it is) only for a day.

27

(94) Although (she was) hired as a bookkeeper, she also does secretarial work.

(Frank, 1972: 245)

g. Adverbial Clauses of Manner

According to Frank (1972: 266-267), adverbial clauses of manner are mostly introduced by the subordinators as, as if, and as though. These subordinators of manner may be preceded by the intensifiers just as shown in (95) and exactly as shown in (96).

(95) They all treat him just AS IF he were a king. (96) She always does exactly AS her husband tells her. (97) He walked around AS THOUGH he was in a daze.

Furthermore, Frank explains that in clauses beginning with as if and as though, two verb forms are possible. The first is indicative form if the speaker is

certain about the statement, and the other is the past subjunctive form if the speaker is more doubtful about statement.

(98) He looks AS IF he needs sleep. (indicative form)

(99) He looks AS IF he needed sleep. (past subjunctive form)

(Frank, 1972: 267) Some as clauses merely indicate the manner in which a statement is made and thus modify the entire sentence. These clauses may appear in any of the three positions of sentence adverbs, whether it is initial, mid or final position.

28

predicate noun, a predicate adjective, a participle, an infinitive and a prepositional phrase, as shown in (100) – (104).

(100) As though (he were) still the king, Lear demanded all the privileges of majesty.

(101) He left the room as though (he were) angry. (102) Everything went off just as (it was) planned. (103) He opened his mouth as if (he were) to speak. (104) His illness disappeared as if (it was) by magic.

h. Adverbial Clauses of Condition

According to Greenbaum and Quirk (1997:316), adverbial clauses of condition convey a ‘direct condition’ in that the situation in the main clause is directly contingent on the situation in the conditional clause. For example, in uttering ‘IF you put the baby down, she’ll scream’ the speaker intends the hearer to undoerstand that the truth of the prediction she’ll scream depends on the fulfillment of the condition of your putting the baby down.

A direct condition may be either open or hypothetical. Open conditions leave unresolved the question of the fulfillment or nonfulfillment of the condition, while hypothetical conditions convey the speaker’s belief that the condition will not be fulfilled (for future conditions), is not fulfilled (for present conditions), or was not fulfilled (for past conditions). The examples can be seen as follows:

(105) If Collin is in London, he is staying at the Hilton. (open) (106) They would be here if they had the time. (hypothetical)

29

Sentence (105) leave unresolved whether Collin is in London and whether he is staying at the Hilton. Therefore, it is an open condition. Meanwhile, sentence (106) convey the implication that they presumably do not have the time and hence the condition is not fulfilled. It is a hypothetical condition for present time.

Greenbaum and Quirk state that the present or future hypothetical meanings are expressed by would/should (or another past-tense modal) plus the infinitive in the main conditioned clause, and by the past tense in the subordinate clause (1972: 747).

The most common subordinators for conditional clauses are if and unless. Most subordinators may be preceded by the intensifiers only, just or not. The examples of the other subordinators can be seen below:

(107) EVEN IF I had known about the meeting, I couldn’t have come. (108) UNLESS it rains, we’ll go to the beach tomorrow.

(109) IN THE EVENT (THAT) the performance is called off, I’ll let you know at once.

(110) IN CASE the robbery occurs in the hotel, the management must be notified at once.

(111) We will be glad to go with you to the theater tonight PROVIDED (THAT) we can get a baby-sitter.

(112) The company will agree to the arbitration ON CONDITION (THAT) the strike is called off at once.

30

(114) She would forgive her husband everything, IF ONLY he would come back to her.

(115) SUPPOSE (THAT) your house burns down. Do you have enough insurance to cover such a loss?

(116) WHETHER she is at home OR WHETHER she visits others, she always has her knitting with her.

(Frank, 1972: 253) To distinguish a hypothetical condition from the open one, Jackson adds that the tense of both the conditional clause and the main clause must be ‘backshifted’. It means that if the condition refers to the present or the future, the tense of the hypothetical condition is backshifted to the past. If the condition refers to the past, the hypothetical condition is backshfted to the past perfect (Jackson, 1990: 205).

The subject and be-form may be omitted from a clause of condition. The retained portion of the predicate may be a predicate noun, a predicate adjective, a prepositional phrase, a present participle or a past participle, as in (117) – (121) below.

(117) If (it is) a success, the experiment could lead the way to many others. (118) If (he is) still alive, he must be at least ninety years.

(119) If (it is) out of the question, please let me now.

(120) If (he is) meeting with too many unexpected difficulties, he will abandon the project.

31

i. Adverbial Clauses of Degree

Clauses of degree can be divided into two main groups, clauses of comparison and clauses of proportion/extent. However, Greenbaum and Quirk have opted out the comparison clause as being one of four major categories of subordinate clauses based on their potential functions, together with nominal/noun clause, adjective/relative clause and adverbial clause (1997: 305). Therefore, the theory discussed here will be only about the comparison clause showing preference and hypothetical circumstances.

The subordinators of comparison clauses which express the choice of preference are rather than and sooner than. Such clauses do not include subjects and they contain only the simple form of verb. In their negative form, not precedes the verb. When such clauses are in final position, rather or sooner may be separated from than and placed with the verb. Here are the examples:

(127) Rather than give up his car, he would give up his house. (128) Sooner than not have his car, he would give up his house.

(129) He would rather (or sooner) give up his home than (give up) his car. (Frank. 1972: 269) As if and as though introduce adverbial clauses indicating comparison

with some hypothetical circumstance (Quirk et al. 1972: 755). The adverbial clause of comparison in hypothetical circumstance implies the unreality of what is expressed in the subordinate clause. From the example below, it is assumed that ‘I am not a stranger.’

32

Proportion clauses express a proportionality or equivalence of tendency or degree between two situations. The clauses may be introduced by as, with or without correlative so, or by fronted correlative the…the followed by comparative forms (Greenbaum and Quirk, 1997: 325). Here are the examples:

(131) As he grew disheartened, his work deteriorated.

(132) As the lane got narrower, the overhanging branches made it more difficult for us to keep sight to our quarry.

(133) The more she thought about it, the less she liked it.

5. The Position and Punctuation of Adverbial Clauses

There are three possible positions for adverbial clauses; initial, medial and final. Frank explains that adverbial clauses in initial position gives more emphasis to the adverbial clause and it also may relate the adverbial clause more closely to the preceding sentence. An introductory adverbial clause is usually set off by commas, especially if the clause is long (Frank, 1972: 234). For example:

(134) If you had listened to me, you wouldn’t have made so many mistakes. (135) Since we live near the sea, we often go sailing.

Adverbial clause in medial position is often between the subject and the verb of the main clause (Greenbaum, 1989: 197). Here, commas must set off the adverbial clause, since it acts as an interrupting element. An adverbial clause in medial position helps to vary the rhythm of the sentence. The example of adverbial clause in medial position are:

33

From the examples (136) and (137), we can see that the adverbial clauses in medial position are inserted between the subject and the verb of the main clauses.

Final position is the most usual position for the adverbial clause. According to Kolln, the punctuation of the subordinate clause is related to the meaning (Kolln, 1990:221). The examples can be seen as follow:

(138) I’ll go to Sue’s party if you promise to be there.

(139) I’m going to the party that Sue’s giving on Saturday night, even though I know I’ll be bored.

In sentence (138), the idea of the main clause will be realized only if the idea in the subordinate clause is carried out. Thus, a comma is not necessary since the main clause depends on the if-clause. However, the adverbial clause in (139) does not affect the fulfillment of the main clause so that it needs a comma. Therefore, in final position, if the adverbial clause defines the situation, it will not be set off by comma from the main clause, but if it simply comments, it will take the comma (Kolln, 1990: 222).

34

C. Theoretical Framework

This study aims to answer problems about the structures and functions of adverbial clauses in the articles on Time magazines. In this part, the application of theories on the research will be explained.

The definition of the adverbial clause helps the writer to give basic understanding on adverbial clause, as the object of the study. This theory, together with the theory of subordinating conjunctions, gives contribution in finding the adverbial clauses in the articles on Time magazines. They subsequently aid to differentiate the adverbial clause from its main clause and the other types of subordinate clause.

35

CHAPTER III

METHODOLOGY

A.

Object of the Study

This is a thesis conducted to study about the structures and functions of

adverbial clauses found in the articles on

Time

Magazines published on May 26

and June 2, 2009. Therefore, the object of this study must be all English complex

sentences containing adverbial clauses. The writer chooses the articles in

Time

Magazines as the sources of the analysis because the languages used in these

magazines are understandable and appropriate for authentic English data.

B.

Method of the Study

In this section, the writer will present the kind of research and the

procedures of the research including data collection and data analysis.

1.

Kind of Research

In his book

An Introduction to General Linguitics

, Dinneen states that

linguistics is a scientific study of language because the empirical methods of the

sciences are employed as much as possible in order to bring the precision and

control of scientific investigation to the study of language (1967: 1). Furthermore,

he mentions that linguistics as a scientific study should be empirical, exact and

objective. Objective means that the conclusion is made based on the evidences

36

evidences which can be proven only. Lastly, exact means that the research results

in precise explanation about the relation of each other elements in language.

Based on the points affirmed above, this thesis is an empirical research.

Chomsky explains that the empirical research is a kind of research based on such

data (1965: 47). The writer used the articles from

Time

Magazines as the source

for the corpus of the analysis. These articles are the primary source because all of

the data was taken from these magazines. Furthermore, this thesis is conducted by

collecting the data and analyzing them to draw a conclusion.

The writer also implements a library research to gain the theories and

information. Those theories and information are mostly obtained from the book in

the library of Sanata Dharma University.

2.

Data Collection

As mentioned previously, the data required for the research were all

English complex sentences containing adverbial clauses. The data were collected

from the articles of

Time m

agazines issued on May 26 and June 2, 2008. There

were total 35 articles in those issues.

In collecting the data, the writer read all the articles to find out the

complex sentences containing adverbial clauses. After that, the data collected

were grouped based on the similarity of subordinator and transition contained in

each construction. Then the data were put in a list. The list of the adverbial clauses

37

3.

Data Analysis

The writer uses written language as the data for the analysis because a

written language is a valid and important object of linguistics investigation

(Gleason 1955: 10). The device on using written material as the data expectedly

will lead into a valid analysis of linguistics too.

Several steps were taken in the process of analyzing the data. The first step

was collecting the data which were all English complex sentences containing

adverbial clauses. The second step was classifying the data into several semantic

functions. They are adverbial clauses of time, adverbial clauses of place, adverbial

clauses of cause/reason, adverbial clauses of result, adverbial clauses of purpose,

adverbial clauses of contrast, adverbial clauses of condition, adverbial clauses of

manner and adverbial clauses of degree. The data were put into a list to simplify

the analysis. The third step was describing the structures of every function of

adverbial clauses. The findings on adverbial clauses, then, will be divided into

finite adverbial clause, non-finite clause, and verbless clause. In this part, the

position and punctuation of the adverbial clauses will also be included. The writer

also gave tables and examples taken from the articles. Finally, the analysis was

38

CHAPTER IV

ANALYSIS

This chapter covers two main parts in accordance with the two problems formulated in Chapter I. The first part will show the findings on the types and functions of adverbial clauses commonly used in the articles of Time Magazines to answer the first problem about the semantic functions of the adverbial clauses. The second part deals with the analysis on the structures of each functions of the adverbial clauses found in the articles to answer the second problem about the syntactic functions of the adverbial clauses. The tables provided will help the explanation further.

A. The Functions of the Adverbial Clauses found in the Articles of Time Magazines

In this part, the writer explains the occurrence of the adverbial clauses in the corpus. Having finished reading all the articles, identifying all complex sentences containing adverbial clauses, and grouping the adverbial clauses into their functions, the writer found that the collected data cover all semantic functions of adverbial clauses as mentioned in the theoretical review.

39

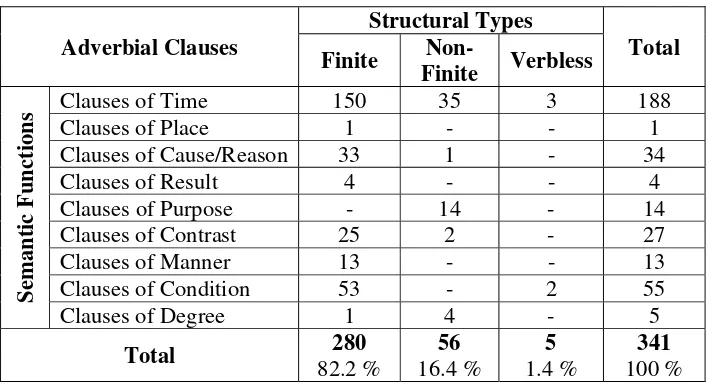

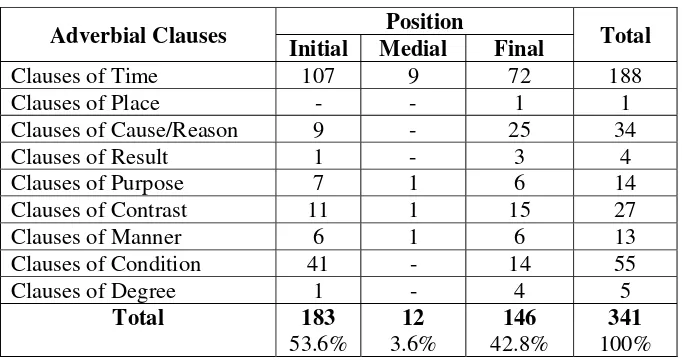

Table 1. The Functions of Adverbial Clauses Found in the Articles of Time Magazines published on May 26 and June 2, 2008

Adverbial Clauses Total Percentage

Clauses of Time 188 55.2 %

Clauses of Place 1 0.3 %

Clauses of Cause/Reason 34 10 %

Clauses of Result 4 1.2 %

Clauses of Purpose 14 4 %

Clauses of Contrast 27 8 %

Clauses of Manner 13 3.8 %

Clauses of Condition 55 16 %

Clauses of Degree 5 1.5 %

Total 341 100 %

From the table above, we can see that the most frequent adverbial clause found in the corpus is the adverbial clause of time which covers more than half of all the adverbial clauses, that is 55.2 %. Jackson states that the time at which two events take place relative to each other is clearly an important piece of information when telling a story or giving a report of something that happened (Jackson, 1990: 200). Therefore, this is suitable to the characteristic of the articles in Time Magazines that reports event or issue in the way of telling a story.

The followings are the functions of the adverbial clauses found in the corpus based on the meaning of the subordinators and the context of the sentences

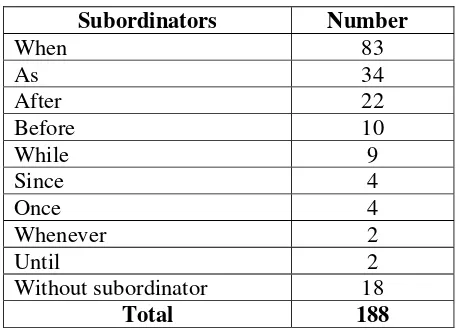

1. Adverbial Clauses of Time

40

Table 2. Subordinators of Adverbial Clause of Time Subordinators Number When 83

As 34

After 22 Before 10

While 9

Since 4 Once 4

Whenever 2

Until 2

Without subordinator 18

Total 188

There are total nine subordinators used to introduce the adverbial clauses in indicating the time when the event in the main clauses happen. Most of those adverbial clauses of time are introduced by the subordinators when, and as. Here

are some examples taken from the corpus:

(1) WHEN night fell in Dujiangyan, a loudspeaker truck cruised the streets broadcasting the same message: “Please stay calm. (26 May 2008, pg. 23)

(2) But since 1990s, AS Manhattan real estate prices have skyrocketed, the distric’s legacy and its perch atop Central Park have enticed real estate developers searching for the next up-and-coming neighborhood. (26 May 2008, pg. 6)

41

(4) ONCE melanoma spreads, it generally cannot be effectively treated with surgery or radiation, which are designed to target contained growths. (26 May 2008, pg. 32)

From the examples taken from the corpus, we can see that the adverbial clause of time relates the time of the situation in its clause to the time of the situation in the main clause, as stated by Greenbaum and Quirk. Some of the subordinators of time may have differences in meaning in indicating the time. The subordinators before and until shows that the time of the main clause may be previous to that of the adverbial clause, as seen in sentence (5) and (6).

(5) They extract a steep up-front investment of time from the reader BEFORE their return their hard, dense nuggets of truth. (26 May 2008,

pg. 34)

(6) Russia will not transcend this dichotomy UNTIL it begins building a truly original future