®

Bonggi Wordlists and

Their Implications

Michael Boutin and Laura Belk

SIL International

®2014

SIL Electronic Working Papers 2014-007, August 2014

© 2014 SIL International®

Abstract Abbreviations

1 Introduction

1.1 The language and its speakers 1.2 History of Bonggi wordlists

2 Description of the data

2.1 Overview of Bonggi phonetics and phonology 2.2 Morphology and morphophonemics

2.2.1 Adjectives 2.2.2 Verbs

2.3 Orthographic conventions

3 Wordlists

3.1 Physical world 3.2 Plants

3.3 Animals 3.4 Human body 3.5 Body functions 3.6 Sense, perception 3.7 Health, life

3.8 Language, thought, emotion 3.9 Social relationships

3.10 Social activity 3.11 Daily life 3.12 Food

3.13 Work and occupation 3.14 Actions

3.15 Quantity 3.16 Size 3.17 Quality 3.18 Time 3.19 Location 3.20 Grammar

4 How many dialects of Bonggi are there?

References

Languages

BDG Bonggi orthography

BL Phonetic data from Ligud, Balambangan ENG English orthography

LD Phonetic data from Limbuak Darat, Banggi Island MAL Malay orthography

PD Phonetic data from Palak Darat, Banggi Island PH Phonetic data from Pasir Hitam, Banggi Island UR Underlying forms (based on Limbuak Darat data)

Grammar

ACC accomplishment verb

ACY activity verb

ATTR attributive

AV.TRAN actor voice transitive verb

CAUS causative

EXPER experiencer subject IMPERF imperfective aspect

IMPERF.ACH imperfective aspect achievement verb PERF perfective aspect

STEAD steady state aspect

The primary purpose of this paper is to make Bonggi wordlists more widely available. Section 1.1 provides background information on the language and its speakers, while §1.2 recounts the history of Bonggi wordlists.

Section 2 discusses various features of the wordlists which are found in §3. Section 2.1 provides a list of phonemes and discusses phonetic and phonological features in the data, while §2.2 discusses the morphological and morphophonemic processes found in the wordlists. Section 2.3 explains the Bonggi orthographic conventions used, and §4 concludes by answering the question – how many dialects of Bonggi are there?

1.1 The language and its speakers

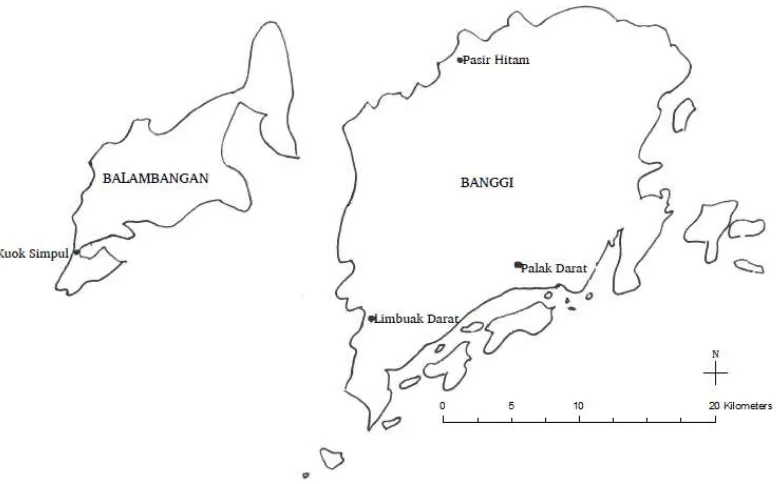

Bonggi is a Malayo-Polynesian language spoken by approximately 1,500 people on Banggi and Balambangan islands in the Kudat District of Sabah, Malaysia. Banggi Island is the largest island in Sabah, and the third largest island in Malaysia. It is separated from Borneo by the Banggi South Channel.

Banggi Island is located approximately 44 kilometers north of Kudat. Since the turn of the 21st century, a daily ferry has been in operation between Kudat on the mainland and Karakit on the

southeastern end of Banggi. Banggi is separated from Balabac, the southernmost island of the Philippine Archipelago, by the 69 km wide Balabac Strait. Balambangan Island is separated from Banggi by a strait 4.8 km wide.1

In July 1764, the Sultan of Sulu gave the British East India Company the rights to both Banggi and Balambangan (Tarling 1978:20). However, it was not until 1773 that the British established a settlement on Balambangan. In early 1775, their garrison was attacked and they were forced to leave Balambangan. The Bonggi are subsistence farmers and fishers. Bonggi agriculture is based on cassava; other crops are maize, bananas, coconuts, papaya, sugar cane, tobacco, tuba (Derris elliptica), areca palms, and betel vine. Most farming is done on an individual household basis, while fishing is a more social activity. Many Bonggi live in small villages of dispersed houses with around 100–150 people per village.2

Bonggi is one of six Malayo-Polynesian minority languages spoken on Banggi, Balambangan, and the surrounding islands. The other five language groups are Suluk, who are referred to as Tausug in the Philippines; Ubian, which is referred to as Sama South Ubihan in Pallesen (1985:3); Kagayan, who migrated from Cagayan de Sulu in the Philippines where they are called Jama Mapun; Balabak, who migrated from Balabac and Ramos islands where they are called Molbog; and Bajau, who are called Sama

(Boutin and Boutin 1985:90). The Bonggi refer to their language and themselves as Bonggi. The word

banggi in their language means ‘corpse’. Although outsiders normally refer to them by the term banggi, because this is a derogatory term, we use the term Bonggi to refer to the people and the language and reserve Banggi to refer to the island.

1.2 History of Bonggi wordlists

The first published Bonggi wordlist appeared in Schneeberger (1937). His wordlist contains 793 items. Although Schneeberger (1937:145) lists 12 Bonggi villages in his paper, he did not state the village(s) where he collected his data. Approximately, 200 lexical items from Schneeberger (1937) are available

1Dalrymple (1769:20-35) provides a good description of Balambangan as does Barton (1769). A good description of

Balambangan bay can be found in Harrisson (1966:102-103). Wells (1981) describes the geology, flora, and fauna of Balambangan.

2For a discussion of Bonggi social organization see Boutin (1990).

electronically in Greenhill, et al. (2008), which is a slight variant of the Swadesh 200-word basic vocabulary list in Blust (1998).

Sometime between October 1978 and November 1979, members of SIL Malaysia collected a wordlist from Lok Agung and Limbuak Darat on Banggi Island (Smith 1984:8). They used a 367-item wordlist which was based on the 372-item wordlist in Reid (1971). For a variety of reasons, the 367-item wordlist was later reduced to a 327-item wordlist for lexicostatical comparison (Smith 1984:45). The wordlists collected by SIL Malaysia members in 1978–1979 were given to the Sabah State Archives, but they have not yet been published.

In September–October 1982, Michael and Alanna Boutin used SIL Malaysia’s 327-item wordlist to collect data from six different languages spoken on Banggi and Balambangan islands. Their data included wordlists from four Bonggi villages: Pengkalan Darat, Pasir Hitam, and Tambising on Banggi Island and Selamat Darat on Balambangan Island (Boutin and Boutin 1985:89). These wordlists were not published.

In 1989 and 1990, Michael Boutin visited all of the Bonggi villages on Banggi and Balambangan islands in order to revise the wordlists collected in 1978–1979 and 1982, and to determine the extent of language variation among the villages. He collected a 337-item wordlist from the following villages with Bonggi village names in parentheses: Limbuak Darat (Pogah Diaa), Mamang (Milimbiaa), Palak Darat (Giparak), Tambising (Tugutah), Sabur (Sabur), Sibumbong Darat (Simbukng), Lok Agung (Indupapa), Pasir Hitam (Pasig Modobm), Kapitangan (Pitangan), Kalang Kaman (Kalanggaman), and Kuda-kuda (Kudah-Kudah). Four of these wordlists are included in §3.

Blust (2010:62) states that Jason Lobel collected a 1,000 word vocabulary of Bonggi. His wordlist is scheduled to be published as part of a North Borneo sourcebook (Lobel, to appear).

Lastly, a working dictionary of over 8,000 Bonggi lexemes is available online (Boutin 2014).3

2 Description of the data

2.1 Overview of Bonggi phonetics and phonology

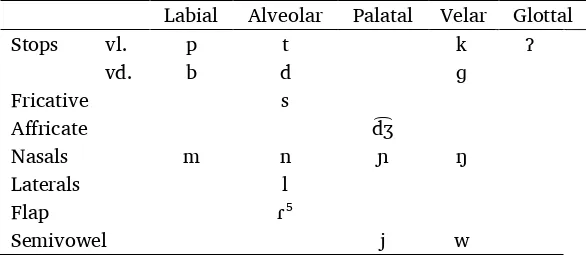

The phonemes of Bonggi are shown in table 1 and table 2.4

Table 1. Bonggi consonant phonemes

Labial Alveolar Palatal Velar Glottal

Stops vl. p t k ʔ

3Michael and Alanna Boutin lived on Banggi Island in Limbuak Darat from January 1983 to April 1986 and in Palak

Darat from November 1987 to April 1992. Michael has made numerous trips to Banggi Island since 1992 with the most recent being October–November 2013.

4Descriptions of Bonggi phonology can be found in Boutin (1993, 2000, 2002, 2010). This paper only discusses

phonetic, phonological, and morphological features found in the wordlists in §3.

5This phoneme is represented by /r/ throughout the rest of the paper.

Table 2. Bonggi vowel phonemes

Front Central Back

High i u

Mid e o

Low a

Stress is predictable; it falls on the penultimate syllable of multisyllabic words as in (1) unless the final syllable is heavy as in (2) and (3) in which case stress is on the final syllable.

(1) /berosi/ [bə.ˈɾo.sʲi] ‘canoe paddle’ /keŋkalaɡ/ [kəŋ.ˈka.ləɡ̚] ‘shadow’

(2) /tetoi/ [tə.ˈtoi] ‘excrement’ /kiou/ [kʲi.ˈou] ‘wood’

Heavy syllables contain either a diphthong as in (2) or a long vowel as in (3). Heavy syllables draw stress and can only occur once in a word—always in the final syllable of a word. Diphthongs and phonetically long vowels are interpreted as two underlying vowels /VV/ which form the nucleus of a heavy syllable. Four vowels, /i u a o/, can be phonetically long [ii uu aa ɔɔ], and five phonetic diphthongs occur, [ei oi ou ai au].

(3) /ɡibiin/ [ɡʲɪ.'ßiiᵈn] ‘afternoon’ /bituun/ [bɪ.ˈtuuᵈn] ‘star’ /biaa/ [bi.ˈaa] ‘crocodile’ /tempoorn/ [təm.ˈpwɔɔɾᵈn] ‘shore’

All consonants can occur in syllable codas except /d͡ʒ/ and /ɲ/. All consonants can occur in syllable onsets except /ʔ/ which only occurs word-finally as in (4).

(4) /tanaʔ/ [ˈta.nə̃ʔ] ‘earth (ground)’ /buaʔ/ [ˈbʷu.əʔ] ‘fruit’

The stops /p b k/ have fricative allophones [ɸβ h] which Schneeberger (1937) recorded as f, w, and

h. The allophone [ɸ] occurs word-initially and intervocalically as in (5); [β] occurs intervocallically within roots as in (6); and [h] occurs intervocallically in unstressed syllables within roots as in (7).

(5) /piiʔ/ [ˈɸiiʔ] ‘hand (and arm)’ /api/ [ˈa.ɸi] ‘fire’

Vowels are nasalized following nasal consonants as in (11).

(11)/tanaʔ/ [ˈta.nə̃ʔ] ‘earth (ground)’ /ani/ [ˈa.nʲĩ] ‘termite’

(12)/mata/ [ˈmã.tə] ‘eye’ /tonok/ [ˈtɔ.nɔ̃k̚] ‘mosquito’

All consonants except semivowels block nasal spread as seen in (13).

(13)/minjait/ [mɪ̃n.ˈ�̃ãĩt̚] ‘lightning’

Word-final nasals are simple if the preceding vowel is nasalized as in (14), but preploded if the preceding vowel is non-nasalized as in (15).

(14)/paŋan/ [ˈɸa.ŋə̃n] ‘companion’ /keŋɡamaŋ/ [kəŋ.ˈɡa.mə̃ŋ] ‘spider’ (15)/baɾam/ [ˈba.ɾəᵇm] ‘many’ /sindoin/ [sʲɪn.ˈdoiᵈn] ‘fingernail’

/tembaŋ/ [ˈtɛm.bəᵏŋ] ‘deer’

The phoneme /o/ can only occur in the penultimate syllable if the final syllable also contains /o/ as in (16) or a high vowel (i.e. /i/ or /u/) as in (17).

(16)/onom/ [ˈɔ.nɔ̃m] ‘six’ /dolok/ [ˈdɔ.lɔk̚] ‘rain’

(17)/bokit/ [ˈbʷo.hɪt̚] ‘bird’ /tolu/ [ˈto.lu] ‘three’

The surface vowels [o] and [ɔ] are in complementary distribution. The phoneme /o/ is realized as [o] in the penultimate syllable if the final syllable contains a high vowel, /i/ or /u/, as in (17). If /o/ is immediately followed by a high vowel as in (19), the two vowels form a diphthong which is the nucleus of a heavy syllable.

(18)/bokit/ [ˈbʷo.hɪt̚] ‘bird’ /obuk/ [ˈo.βʷʊk̚] ‘hair’

(19)/oid/ [ˈoid̚] ‘boat’ /loud/ [ˈloud̚] ‘sea’

The allophone [ɔ] occurs only if the last two vowels in the word are [ɔ]. The phoneme /o/ is realized as [ɔ] in the penultimate syllable if the final syllable also contains an /o/ which is realized as [ɔ] as in (20). If /o/ is immediately followed by another /o/ as in (21), the two vowels form a

phonetically long vowel [ɔɔ] which is the nucleus of a heavy syllable.

(20)/dolok/ [ˈdɔ.lɔk̚] ‘rain’ /dodos/ [ˈdɔ.dɔs] ‘wind’

(21)/tempoorn/ [təm.ˈpwɔɔɾᵈn] ‘shore’ /koo/ [ˈkʷɔɔ] ‘wing’

2.2 Morphology and morphophonemics

The three major word classes which occur in the wordlists are nouns, adjectives, and verbs. Minor word classes include quantifiers (e.g. §3.15) and negators (e.g. §3.20). All nouns and minor word classes in the wordlists are bare roots. The following two sections briefly discuss the grammatical morphemes which are found in the wordlists in §3. Most of the affixes described are prefixes which occur on verbs.

2.2.1 Adjectives

Some adjectives can occur either as a bare root or with the attributive prefix /m-/1 ‘ATTR’ as in (22).

Other adjectives such as me-langgu ‘ATTR-long’ in (23) always occur with the prefix m- ‘ATTR’. Still other adjectives such as baru ‘new’ in (24) never occur with the prefix m- ‘ATTR’.

(22)/panas/ [ˈɸa.nə̃s] ‘hot (as water)’ /m-/1 /panas/ [m̩.ˈpa.nə̃s] ‘hot (as water)’

(23) /m-/1 /laŋɡu/ [mə̃.ˈlaŋ.ɡʷu] ‘long (object)’

If the nasal prefix m- ‘ATTR’ occurs before non-sonorant consonants, it assimilates to the same point

of articulation as the following non-sonorant consonant as in (25).6 The underlying form /m-/

1 ‘ATTR’

occurs before vowel-initial roots as seen in(26).

(25)/m-/1 /peit/ [m̩.ˈpeit̚] ‘bitter’ /m-/1 /doot/ [n̩.ˈdɔɔt̚] ‘bad’

/m-/1 /kapal/ [ŋ̍.ˈka.ɸal] ‘thick (object)’

(26)/m-/1 /omis/ [ˈmʷõ.mɪ̃s] ‘sweet’ /m-/1 /iŋad/ [ˈmĩ.ŋə̃d̚] ‘near’

If the nasal prefix m- ‘ATTR’ occurs before sonorant consonants, an epenthetic vowel is inserted

between the nasal prefix m- ‘ATTR’ and the initial consonant of the root as in (27) and (28).

(27)/m-/1 /laŋɡu/ [mə̃.ˈlaŋ.ɡʷu] ‘long (object)’ /m-/1 /lompuŋ/ [mə̃.ˈlom.pʷʊᵏŋ] ‘fat (adj.)’

(28)/m-/1 /nipis/ [mɪ̃.ˈnʲĩ.ɸɪs] ‘thin (object)’

The epenthetic vowel in (27) and (28) is a copy of the controlling vowel, which is the first vowel of the root. The contrast between the non-high vowels (i.e. /e/, /o/, and /a/) is neutralized as [ə] in prestressed syllables. Thus, in (27) the contrast between the epenthetic vowels /a/ and /o/ is neutralized as [ə]. In (28) the epenthetic vowel /i/ is laxed, because it occurs in a prestressed syllable preceding a consonant.

2.2.2 Verbs

Bonggi has a class of activity verbs that are marked by/-m-/1 ‘ACY’. This affix is realized as an infix, if it

occurs with non-bilabial consonant-initial roots as in (29). The infix is inserted after the initial consonant of the root. Because complex syllable onsets are not permitted, an epenthetic vowel is inserted between the initial consonant of the root and the infix. The epenthetic vowel is a copy of the controlling vowel which is the first vowel of the root. If the epenthetic vowel is a non-high vowel, it is neutralized as [ə]. If the epenthetic vowel is a high vowel (i.e. /i/ or /u/), it is laxed.

(29)/-m-/1 /suka/ [sʊ.ˈmʷu.hə] ‘to vomit’ /-m-/1 /toi/ [tə.ˈmʷõĩ] ‘to defecate’

A second infix /-m-/2 ‘ACC’ marks accomplishment verbs, but only occurs once in the wordlists. It is

inserted after the initial consonant of roots, which begin with a non-bilabial consonant as in (31). An epenthetic vowel is inserted between the initial consonant of the root and the infix. If the epenthetic vowel is a non-high vowel, it is neutralized as [ə].

(31)/-m-/2 /ɡalak/ [ɡə.ˈmã.lək̚] ‘to boil (intrans.)’

Achievement verbs are a third class of verbs. They occur infrequently in the wordlists. Imperfective achievement verbs are marked by /m-/3 ‘IMPERF.ACH’ as in (32) and (33). If /m-/3 attaches to a

consonant-initial root as in (32), an epenthetic vowel is inserted between the prefix and the initial consonant of the root. The epenthetic vowel is a copy of the controlling vowel which is the first vowel of the root. If the epenthetic vowel is a non-high vowel, it is neutralized as [ə].

6Syllabic nasals [m̩], [n̩], and [ŋ̍] occur word-initially before nasals and homorganic obstruents. A raised syllabic

marker is used to show syllabicity on nasals with descenders (Pullum and Ladusaw 1996:306).

(32)/m-/3 /dabuʔ/ [mə̃.ˈda.βuʔ] ‘to fall (drop)’ /m-/3 /teiɾn/ [mə̃.ˈtʲeiɾᵈn] ‘to lose’

(33)/m-/3 /udap/ /-an/ [mʷũ.ˈda.ɸəᵈn] ‘hungry’

The wordlists in §3 contain some verbs of perception or cognition, which have an experiencer subject marked by the prefix /k-/ ‘EXPER’ as in (34) and (35).

(34)/k-/ /dooɾ/ [kə.ˈdɔɔɾ] ‘to hear’ /k-/ /tonduʔ/ [kə.ˈton.duʔ] ‘to know (person)’ (35)/k-/ /liid/ [kʲɪ. ˈlʲiid̚] ‘to see’ /k-/ /lipat/ [kʲɪ.ˈlʲi.ɸət̚] ‘to forget’

An epenthetic vowel is inserted between the prefix /k-/ ‘EXPER’ and the initial consonant of

consonant-initial roots. The epenthetic vowel is a copy of the controlling vowel which is the first vowel of the root. If the epenthetic vowel is a non-high vowel, it is neutralized as [ə] as in (34). If the

epenthetic vowel is a high vowel, it is laxed as in (35).

Another class of verbs has steady-state aspect, which is marked by the prefix /ɡ-/ ‘STEADY’ as seen in

(36) and (37).7

(36)/ɡ-/ /itoot/ [ɡʲɪ.ˈtɔɔt̚] ‘to lie (untruth)’ /ɡ-/ /ubu/ [ˈɡʷu.βʷu] ‘to laugh’ (37)/ɡ-/ /ɾampus/ [ɡə.ˈɾam.pʷʊs] ‘to be angry’ /ɡ-/ /nipi/ [ɡɪ.ˈnʲĩ.ɸi] ‘to dream’

The examples in (36) contain vowel-initial roots, whereas those in (37) contain consonant-initial roots. An epenthetic vowel is inserted between the prefix /ɡ-/ ‘STEADY’ and the initial consonant of

consonant-initial roots. The epenthetic vowel is a copy of the controlling vowel, which is the first vowel of the root. If the epenthetic vowel is a non-high vowel, it is neutralized as [ə]. However, if it is a high vowel, it is laxed.

Some verbs are derived from noun roots by the prefix /ɡ-/ ‘STEADY’ as illustrated in (38), where the

verb nggapi ‘to cook’ is derived from the noun api ‘fire’. The verb nggapi ‘to cook’ contains three morphemes: 1) the noun root api ‘fire’, 2) the derivational prefix /ɡ-/ ‘STEADY’, and 3) the inflectional

prefix /m-/2 ‘IMPERF’ marking imperfective aspect. The perfective form of this verb is igapi ‘was cooked’

with the inflectional prefix /i-/ ‘PERF’ marking perfective aspect.

(38)/api/ [ˈa.ɸi] ‘fire’ /m-/2 /ɡ-/ /api/ [ŋ̩̩̩.ˈɡa.ɸi] ‘to cook’

Some verb stems, which are marked by /ɡ-/ ‘STEADY’, e.g., ‘cook’ in (38) are always inflected with imperfective or perfective aspect, whereas other verb stems like those in (36) and (37) can appear without an inflectional prefix. The verbs in (36) and (37) can be inflected with /m-/2 ‘IMPERF’ or /i-/

‘PERF’ aspect. When elicting wordlists, language consultants provided either uninflected verbs stems or imperfective aspect forms.

The causative prefix /p-/ ‘CAUS’ is illustrated in (39). An epenthetic vowel is inserted between the prefix /p-/ ‘CAUS’ and the initial consonant of consonant-initial roots. Because the epenthetic vowel in (39) is non-high, it is realized as [ə].

(39)/p-/ /boli/ [ɸə.ˈβʷo.lʲi] ‘to sell’

Bonggi has a class of actor voice transitive verbs, which are marked by the prefix /ŋ-/ ‘AV.TRAN’.If

the root begins with a voiceless consonant or /b/, the /ŋ/ and the root-initial consonant coalesce, and are then replaced by a nasal homorganic to the root-initial consonant, as seen in (40).

(40)/ŋ-/ /poɾoʔ/ [ˈmʷɔ̃.ɾɔʔ] ‘to tell’ /ŋ-/ /boɾi/ [ˈmʷõ.ɾʲi] ‘to give’ /ŋ-/ /tanam/ [ˈnã.nə̃m] ‘to plant’ /ŋ-/ /sipak/ [ˈnʲĩ.ɸək̚] ‘to kick’ /ŋ-/ /kokol/ [ˈŋʷɔ̃.hwɔl] ‘to bite’

7For a discussion of steady-state aspect see Talmy (2007:107).

The underlying form /ŋ-/ ‘AV.TRAN’occurs before vowel-initial roots as seen in (41). (41)/ŋ-/ /adak/ [ˈŋã.dək̚] ‘to smell something’ /ŋ-/ /inum/ [ˈŋʲĩ.nũm] ‘to drink’

As seen in (42), coalescence does not occur with voiced consonants other than /b/. Instead, an epenthetic vowel is inserted between the prefix /ŋ-/ ‘AV.TRAN’and the root-initial consonant. If the

epenthetic vowel is a non-high vowel, it is neutralized as [ə]. However, if it is a high vowel, it is laxed.

(42)/ŋ-/ /loboŋ/ [ŋə̃.ˈlɔ.βɔᵏŋ] ‘to bury (the dead)’ /ŋ-/ /laak/ [ŋə̃.ˈlaak̚] ‘to dry in sun’ /ŋ-/ /ɾiaak/ [ŋʲɪ̃.ɾʲi.ˈaak̚] ‘to pull’

The wordlists contain three examples in which the first syllable of the root is reduplicated. They are shown in (43).

(43)/CV-/ /toi/ [tə.ˈtoi] ‘excrement’ /CV-/ /suad/ [sʊ.ˈsu.əd̚] ‘story’ /CV-/ /bali/ [bə.ˈβa.lʲi] ‘to play’

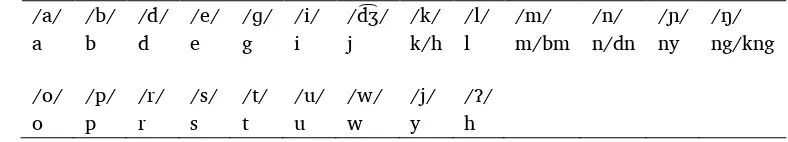

2.3 Orthographic conventions

Presently, there is no official standard orthography for Bonggi. Table 3 shows the orthographic conventions that are used in this paper to represent each phoneme. For example, the phoneme /d͡ʒ/ is represented by the orthographic symbol j and a glottal stop /ʔ/ is represented by h. Some phonemes are overdifferentiated; that is, they are represented in more than one manner in the orthography even though the distinction is not phonemic. For example, word-final nasals are written with a homorganic stop immediately preceding the nasal, if they are preploded. However, they are written as plain nasals, if they are not preploded. Underdifferentiation also occurs because two phonemes are written as h. Word-final h represents glottal stop (which only occurs word-finally), while word-medial h is an allophone of /k/. The contrast between non-high vowels /e/, /a/, and /o/ is neutralized as [ə] in prestressed position and written as e.

The wordlists in §3 are organized by semantic domain. The language consultants who provided the Bonggi data below were: Liad bin Alok from Limbuak Darat (Banggi Island), Timisup from Palak Darat (Banggi Island), Sukia from Pasir Hitam (Banggi Island), and Lina binti Francis and Menaku bin Tutut from Kuok Simpul (Balambangan Island).8 See figure 1 for the location of these four villages.

8Bonggi names consist of a first name followed by one’s father’s name with bin meaning ‘son of’ and binti meaning

‘daughter of’. For example, Liad bin Alok refers to ‘Liad son of Alok’. The father’s name of two language consultants

is unknown, because it was not elicited for cultural reasons. It is taboo to say the name of one’s parents or the name of dead people. Thus, one should not ask someone what his/her father’s name is, especially if he is already dead.

Figure 1. Locations of villages where four wordlists were collected.

3.1 Physical world

ENG water river sea shore sand mud earth (ground)

MAL air sungai laut pantai pasir lumpur tanah

BDG beig sungi loud tempoordn pasig lusak tanah

UR /beiɡ/ /suŋi/ /loud/ /tempoorn/ /pasiɡ/ /lusak/ /tanaʔ/ LD [ˈbeiɡ̚] [ˈsu.ŋʲĩ] [ˈloud̚] [təm.ˈpwɔɔɾᵈn] [ˈɸa.sʲɪɡ̚] [ˈlu.sək̚] [ˈta.nə̃ʔ]

PD [ˈbeiɡ̚] [ˈsu.ŋʲĩ] [ˈloud̚] [təm.ˈpwɔɔɾᵈn] [ˈɸa.sʲɪɡ̚] [ˈlu.sək̚] [ˈta.nə̃ʔ]

PH [ˈbeiɡ̚] [ˈsu.ŋʲĩ] [ˈloud̚] [təm.ˈpwɔɔɾᵈn] [ˈɸa.sʲɪɡ̚] [ˈlu.sək̚] [ˈta.nə̃ʔ]

BL [ˈbeiɡ̚] [ˈsu.ŋʲĩ] [ˈloud̚] [təm.ˈpwɔɔɾᵈn] [ˈɸa.sʲɪɡ̚] [ˈlu.sək̚] [ˈta.nə̃ʔ]

ENG mountain stone wood woods (forest) bark (of tree)

MAL gunung batu kayu hutan kulit kayu

BDG buid batu kiou toidn kuluak kiou

UR /buid/ /batu/ /kiou/ /toin/ /kuluak kiou/

ENG crocodile turtle frog (generic)10 fish (generic) snake

ENG worm (earth) termite spider lice (head) lice (chicken) mosquito MAL cacing tanah anai-anai labah-labah kutu kutu ayam nyamuk

BDG lingguakng ani kenggamang kutu kutu tonok

10There is no generic term for frog. The two terms that were elicited most frequently were [ˈbʷu.βək̚] ‘a type of large

frog’ and [bɪ.ɾʲi.ˈha.tək̚] ‘a type of small frog’.

ENG skin (of person) scar boil (infection) blood vein (blood) bone

ENG brain throat (esophagus) lungs heart rib liver intestines

MAL otak tekak, korongkong paru-paru jantung tulang rusuk hati (e.g., hati babi)

bongol ngadak tuug tiguru

UR /k-/ /iid/

11Besides coalescence of /ŋ-/ with the initial consonant of the root, /l/ undergoes metathesis and then is vocalized as

[i]. See Boutin (2010) for a description of these morphophonemic processes.

12The choice between [kə.ˈdɔɔɾ] ‘hear’ and [kə.ˈdɔŋɔɾ] ‘hear’ is individual, not dialectal.

PD [ˈkʲiid̚]

[kʲɪ.ˈlʲiid̚] [ˈbʷu.ləɡ̚][ˈbʷu.tə] [kə.ˈdɔ

.ŋɔɾ] [ˈbʷɔ.ŋʷɔ̃l] [ˈŋã.dək̚] [ˈtuuɡ tʲɪ.ˈhʷu.ɾu]

PH [ˈkʲiid̚]

[kʲɪ.ˈlʲiid̚] [ˈbʷu.ləɡ̚][ˈbʷu.tə] [kə.ˈdɔɔɾ] [ˈbʷɔ.ŋʷɔ̃l] [ˈŋã.dək̚] [ˈtuuɡ tʲɪ.ˈɡʷu.ɾu] BL [ˈkʲiid̚]

[kʲɪ.ˈlʲiid̚] [ˈbʷu.ləɡ̚] [kə.ˈdɔɔɾ] [ˈbʷɔ.ŋʷɔ̃l] [ˈŋã.ɾək̚] [ˈtuuɡ tʲɪ.ˈhʷu.ɾu]

3.7 Health, life

ENG pain itchy medicine dead to bury (the dead) grave to kill

MAL sakit gatal ubat mati menguburkan kubur bunuh

BDG sahit katal uru mati ngelobokng lobokng mmati

UR /sakit/ /katal/ /uɾu/ /mati/ /ŋ-/ /loboŋ/ /loboŋ/ /m-/2 /mati/13

LD [ˈsa.hit̚] [ˈka.tal] [ˈu.ɾu] [ˈmã.tʲi] [ŋə̃.ˈlɔ.βɔᵏŋ] [ˈlɔ.βɔᵏŋ] [m̩.ˈmã.tʲi] PD [ˈsa.hit̚] [ˈka.tal] [ˈu.ɾu] [ˈmã.tʲi] [ŋə̃.ˈlɔ.βɔᵏŋ] [ˈlɔ.βɔᵏŋ] [m̩.ˈmã.tʲi] PH [ˈsa.hit̚] [ˈka.tal] [ˈu.ɾu] [ˈmã.tʲi] [ŋə̃.ˈlɔ.βɔᵏŋ] [ˈlɔ.βɔᵏŋ] [m̩.ˈmã.tʲi] BL [ˈsa.hit̚] [ˈka.tal] [ˈu.ɾu] [ˈmã.tʲi] [ŋə̃.ˈlɔ.βɔᵏŋ] [ˈlɔ.βɔᵏŋ] [m̩.ˈmã.tʲi]

3.8 Language, thought, emotion

ENG to speak to tell to call to answer to lie (untruth) name

MAL cakap beritahu panggil jawab bohong nama

BDG suad moroh noog mabat gitoot ngaardn

UR /suad/ /ŋ-/ /poɾoʔ/ /ŋ-/ /tooɡ/ /-m-/1 /abat/ /ɡ-/ /itoot/ /ŋaaɾn/

LD [ˈsu.əd̚] [ˈmʷɔ̃.ɾɔʔ] [ˈnɔ̃ɔ̃ɡ̚] [ˈmã.βət̚] [ɡʲɪ.ˈtɔɔt̚] [ˈŋããɾᵈn] PD [ˈsu.əd̚] [ˈmʷɔ̃.ɾɔʔ] [ˈnɔ̃ɔ̃ɡ̚] [ˈmã.βət̚] [ɡʲɪ.ˈtɔɔt̚] [ˈŋããɾᵈn] PH [ˈsu.əd̚] [ˈmʷɔ̃.ɾɔʔ] [ˈnɔ̃ɔ̃ɡ̚] [ˈmã.βət̚] [ɡʲɪ.ˈtɔɔt̚] [ˈŋããɾᵈn] BL [ˈsu.əd̚] [ˈmʷɔ̃.ɾɔʔ] [ˈnɔ̃ɔ̃ɡ̚] [ˈmã.βət̚] [ɡʲɪ.ˈtɔɔt̚] [ˈŋããɾᵈn]

ENG story dream to dream to know (person) to forget to choose

MAL cerita mimpi mimpi kenal lupa pilih

BDG susuad nipi ginipi ketonduh kilipat milih

UR /CV-/ /suad/ /nipi/ /ɡ-/ /nipi/ /k-/ /tonduʔ/ /k-/ /lipat/ /ŋ-/ /piliʔ/ LD [sʊ.ˈsu.əd̚] [ˈnʲĩ.ɸi] [ɡɪ.ˈnʲĩ.ɸi] [kə.ˈton.duʔ] [kʲɪ.ˈlʲi.ɸət̚] [ˈmĩ.lʲiʔ] PD [sʊ.ˈsu.əd̚] [ˈnʲĩ.ɸi] [ɡɪ.ˈnʲĩ.ɸi] [kə.ˈton.duʔ] [kʲɪ.ˈlʲi.ɸət̚] [ˈmĩ.lʲiʔ] PH [sʊ.ˈsu.əd̚] [ˈnʲĩ.ɸi] [ɡɪ.ˈnʲĩ.ɸi] [kə.ˈton.duʔ] [kʲɪ.ˈlʲi.ɸət̚] [ˈmĩ.lʲiʔ] BL [sʊ.ˈsu.əd̚] [ˈnʲĩ.ɸi] [ɡɪ.ˈnʲĩ.ɸi] [kə.ˈton.duʔ] [kʲɪ.ˈlʲi.ɸət̚] [ˈmĩ.lʲiʔ]

13This verb is irregular and the underlying form is slightly different from that shown here.

ENG to be angry to be ashamed to be afraid to cry (weep) to laugh tear (from crying)

ENG mother father offspring child companion sibling

PD [ɸə.ˈβʷo.lʲi] [ˈmʷõ.lʲi] [mĩ.ˈããɾ] [ˈu.təᵏŋ]

MAL tikar menganyam jahit jarum cawat, kain punggung celana

BDG serah matur neih jarubm simbeit suruar

14The form metak ‘to live’ involves haplology.

3.12 Food

ENG wine (rice) coconut (unripe) coconut (ripe) coconut shell ladle banana lime

MAL tapai kelapa muda kelapa tua gayung pisang kapur

ENG eggplant chicken egg peanut ginger cassava (tapioca)

MAL terung ayam telur kacang tanah halia ubi kayu

BDG talubm manuk tilug kasakng tanah liaa sikiou

UR /talum/ /manuk/ /tiluɡ/ /kasaŋ tanaʔ/ /liaa/ /sikiou/ LD [ˈta.lʊᵇm] [ˈmã.nʊ̃k̚] [ˈtʲi.lʊɡ̚] [ˈka.səᵏŋˈta.nə̃ʔ] [lʲi.ˈaa] [sʲɪ.kʲi.ˈou] PD [ˈta.lʊᵇm] [ˈmã.nʊ̃k̚] [ˈtʲi.lʊɡ̚] [ˈka.səᵏŋ ˈta.nə̃ʔ] [lʲi.ˈaa] [sʲɪ.lʲɪ.kʲi.ˈou] PH [ˈta.lʊᵇm] [ˈmã.nʊ̃k̚] [ˈtʲi.lʊɡ̚] [ˈka.səᵏŋ ˈta.nə̃ʔ] [lʲi.ˈaa] [sʲɪ.lʲɪ.ˈhou] BL [ˈta.lʊᵇm] [ˈmã.nʊ̃k̚] [ˈtʲi.lʊɡ̚] [ˈka.səᵏŋ ˈta.nə̃ʔ] [lʲi.ˈaa] [sʲɪ.kʲi.ˈou]

ENG sugar cane salt areca nut betel leaf15 to chew betel nut to bite

15The term biuʔrefers to domesticate betel leaf purchased in Kudat, whereas anggar is a wild variety of betel leaf found

in the jungle.

PD [ˈto.βʷu] [ˈtʲi.mʷʊ̃s] [ˈlu.ɡʷʊs] [ˈbi.uʔ]

BDG mohodn nginum nggapi lanjakng gemalak ngelaak

UR /-m-/1 /okon/ /ŋ-/ /inum/ /m-/2 /ɡ-/ /api/ /land͡ʒaŋ/ /-m-/2 /ɡalak/ /ŋ-/ /laak/

MAL perahu dayung rakit menyumpit menimbak

BDG oid berosi rahit nopuk nimbak

16There is no generic word meaning ‘hunt’.

ENG to stab sheath for machete fence rope to tie (tether animal)

MAL berjalan kaki lari berenang duduk berdiri pulang

BDG mpanu lemompud lemongi mupug musag mulih

BDG nggait meteirdn medabuh getaruh gerapat

3.15 Quantity

ENG big small (object) long (object) short (person) short (object)

ENG thick (object) thin (object) wide narrow handspan (8")

LD [ˈi.nə̃k̚] [mə̃.ˈlom.pʷʊᵏŋ] [ˈtu.hal] [mʷũ.ˈda.ɸəᵈn] [m̩.ˈbi.əɡ̚] [ˈɸʷo.nũʔ] PD [ˈi.nə̃k̚] [mə̃.ˈlom.pʷʊᵏŋ] [ˈtu.hal] [mʷũ.ˈda.ɸəᵈn] [m̩.ˈbi.əɡ̚] [ˈɸʷo.nũʔ] PH [ˈi.nə̃k̚] [mə̃.ˈlom.pʷʊᵏŋ] [ˈtu.hal] [mʷũ.ˈda.ɸəᵈn] [m̩.ˈbi.əɡ̚] [ˈɸʷo.nũʔ] BL [ˈi.nə̃k̚] [mə̃.ˈlom.pʷʊᵏŋ] [ˈtu.hal] [mʷũ.ˈda.ɸəᵈn] [m̩.ˈbi.əɡ̚] [ˈɸʷo.nũʔ]

ENG deep hard (substance) heavy strong straight fast (adj.)

BDG modobm putih segah misinu megbeig benglei

UR /m-/1 /odom/ /putiʔ/ /seɡaʔ/ /misinu/ /meɡ-/ /beiɡ/ /beŋlei/

17Megbeig benglei ‘yellow’ is a derived color term in Bonggi. Benglei is a type of medicinal plant, and beig means

‘water’. Megbeig benglei means ‘like the water around a benglei plant’.

ENG yesterday last night tomorrow long time year

18Note that “what,” “when,” “where,” “who,” and “how many” are question words.

ENG not (e.g., It is not a pig.) not (e.g., He is not running.) other (different) same

4 How many dialects of Bonggi are there?

Schneeberger (1937) made the first published claim that Bonggi has more than one dialect.

“On the island Balambangan, which is separated from Banggi by a strait 3 miles wide, a few families of Banggi Dusun have lived for some generations. Within this relative short time they have developed a particular dialect. A comparative study of these two dialects would be interesting from a lingusitic point of view” (Schneeberger 1937:145).

The two 1978–1979 Bonggi wordlists collected on Banggi Island by members of SIL Malaysia were part of a large database that is described in Smith (1984:2). Every word from each wordlist was assigned to a cognate set.19 The percentage of shared cognates from the two Bonggi vilages was 88% (Smith

1984:8). This 12% difference between two villages on Banggi Island together with Schneeberger’s claim of a Balambangan dialect and sociolinguistic data, led Boutin and Boutin (1985:89) to perpetuate Schneeberger’s claim of a distinct Balambangan dialect.

“By comparing wordlists and talking with Banggi people it is clear that there are at least two dialects of the Banggi language. One of these dialects is located on Balambangan Island and the other on Banggi Island” (Boutin and Boutin 1985:89).

The claim that the Bonggi spoken on Balambangan Island is different from the Bonggi spoken on Banggi Island has also been made over the years by the Bonggi themselves.

When the wordlists in §3 were collected, Boutin had an advantage over previous investigators in that he spoke Bonggi and he had already drafted a description of the phonology (see Boutin 1993). Previous investigators had no way of judging the adequacy of the language consultant’s responses.

Several phonetic features are not transcribed in Schneeberger’s (1937) and Greenhill, et al.’s (2008) wordlists including: stress, palatalization of consonants as in (8), labialization of consonants as in (9), and unreleased stops as in (10).

Schneeberger did not always transcribe glottal stops which are phonemic word-finally. For example,

kaha ‘older sibling’ has a final glottal stop /kakaʔ/ [ˈka.həʔ] as does ama ‘father’, which should be transcribed /amaʔ/ [ˈa.mə̃ʔ].20 Other times he apparently heard glottal stop as a word-final k in some

words such as buak ‘fruit’ which should be transcribed /buaʔ/ [ˈbʷu.əʔ]. Since k also occurs word-finally (e.g. manuk ‘chicken’), this leads to an absence of contrast in Schneeberger’s data between word-final glottal stop /ʔ/ and word-final /k/.

Schneeberger (1937) was also inconsistent in his phonetic representation of word-final preploded nasals. For example, he recorded /sindoin/ [sʲɪn.ˈdoiᵈn] ‘fingernail’ (15) as sindoidn, but /libun/ [ˈlʲi.βʷʊᵈn] ‘woman (female)’ as liwun rather than liwudn.

19Cognates were not determined via reconstruction; instead, they were assigned by a simple “spot cognate” method.

20The stops /p b k/ have fricative allophones [ɸβ h] which Schneeberger (1937) recorded as as f, w, and h (see (5),

(6), and (7)).

Schneeberger transcribed the schwa [ə] as ĕ and syllabic nasals [m̩], [n̩], and [ŋ̍] as ĕm, ĕn, and ĕng. For example, /m-/1 /peit/ [m̩.ˈpeit̚] ‘bitter’, /ndaʔ/ [ˈn̩.dəʔ] ‘not’, and /m-/2 /ɡ-/ /ait/ [ŋ.ˈɡait̚] ‘to wait’

were transcribd by him as ĕmpeit, ĕndak, and ĕnggait.

Schneeberger (1937:149) has chara for ‘have/exist’ (Malay ada), but there is no c or ch in Bonggi. The correct form is /kiara/ [kʲiˈ.a.ɾə] ‘have/exist’.

Besides a number of inconsistent and unreliable phonetic representations, it is very difficult for investigators who do not speak the target language to spot inadequate equivalents when collecting wordlists. For example, Bonggi does not have a generic term for frog. The two terms that were elicited from Malay katak ‘frog’ by Boutin are [ˈbʷu.βək̚] ‘a type of large frog’ and [bɪ.ɾʲi.ˈha.tək̚] ‘a type of small frog’. An example of an inadequate equivalent in Schneeberger (1937) is awan for Malay awan ‘cloud’ rather than /toi landas/ [ˈtoi ˈlan.dəs] ‘cloud’.

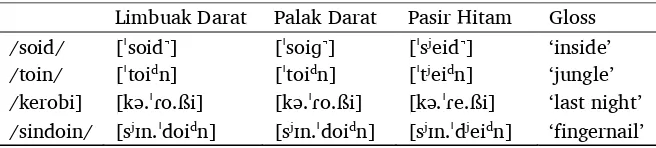

The wordlists in §3 provide no lexical evidence for more than one dialect of Bonggi. However, they do provide evidence of phonetic variation. There is a phonetic variation in some words between word-final [d] and word-final [ɡ] with the former occurring in Limbuak Darat (and other Bonggi villages on the southwestern portion of Banggi Island) and the latter occurring in Palak Darat (and other Bonggi villages on the eastern side of Banggi Island). There is also a phonetic variation in some words between [e] and [o] with the former occurring in Pasir Hitam (and other villages on the northwestern part of Banggi island) and the latter occurring on the southwestern and eastern side of Banggi Island. Table 4 provides examples of these phonetic differences.

Table 4. Regional pronunciation differences

Limbuak Darat Palak Darat Pasir Hitam Gloss

/soid/ [ˈsoid̚] [ˈsoiɡ̚] [ˈsʲeid̚] ‘inside’

/toin/ [ˈtoiᵈn] [ˈtoiᵈn] [ˈtʲeiᵈn] ‘jungle’

/kerobi] [kə.ˈɾo.ßi] [kə.ˈɾo.ßi] [kə.ˈɾe.ßi] ‘last night’ /sindoin/ [sʲɪn.ˈdoiᵈn] [sʲɪn.ˈdoiᵈn] [sʲɪn.ˈdʲeiᵈn] ‘fingernail’

Two conclusions can be draw from the evidence in this paper. First, collecting phonetically accurate wordlists is very difficult for investigators who do not speak the target language. Second, there is no lexical evidence for more than one dialect of Bonggi including a distinct Balambangan dialect.

Barton, James, Lieut. 1769. Balambangan. Reprinted in The British North Borneo Herald 5(7):169–170, 1887.)

Blust, Robert. 1998. The position of the languages of Sabah. Pagtanáw: Essays on language in honor of Teodoro A. Llamzon, ed. by Ma. Lurdes S. Bautista, 29–52. Manila: The Linguistic Soceity of the Philippines.

Blust, Robert. 2010. The greater North Borneo hypothesis. Oceanic Linguistics 49(1).44–118.

Boutin, Michael. 1990. The Bonggi. Social organization of Sabah societies, ed. Sherwood G. Lingenfelter, 91–110. Kota Kinabalu: Sabah Museum and State Archives.

Boutin, Michael. 1993. Bonggi phonemics. Phonological descriptions of Sabah languages, ed. by Michael Boutin and Inka Pekkanen, 107–130. (Sabah Museum Monograph 4.) Kota Kinabalu: Sabah Museum. Boutin, Michael. 2000. The role of /l/ in blocking nasal spread in Bonggi. Borneo 2000: Language,

management and tourism. Proceedings of the Sixth Biennial Borneo Research Conference, ed. by Michael Leigh, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, 170–188. Kuching: Institute of East Asian Studies, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak.

Boutin, Michael. 2002. Blocking nasal spread in Bonggi. Papers from the Tenth Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 2000, ed. by Marlys Macken, 97–114. Tempe, AZ: Program for Southeast Asian Studies, Arizona State University.

Boutin, Michael. 2010. Metathesis in Bonggi. Piakandatu ami Dr. Howard P. McKaughan, ed. by Loren Billings and Nelleke Goudswaard, 52–63. Manila: Linguistic Society of the Philippines and SIL Philippines.

Boutin, Michael. 2014. Bonggi – English – Malay dictionary. Online: http://bonggi.webonary.org/. (Accessed 21 June 2014.)

Boutin, Michael, and Alanna Boutin. 1985. Report on the languages of Banggi and Balambangan. Sabah Society Journal 8(1):89–92.

Dalrymple, Alexander. 1769. A plan for extending the commerce of this kingdom and of the East-India Company. London.

Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.). 2005. Ethnologue: Languages of the world, 15th edition. Dallas, TX: SIL International.

Greenhill, Simon J., Robert Blust, and Russell D. Gray. 2008. The Austronesian Basic Vocabulary Database: From Bioinformatics to Lexomics. Evolutionary Bioinformatics, 4:271–283. Online: http://language.psy.auckland.ac.nz/austronesian/language.php?id=3 (Accessed 21 June 2014). Grimes, Barbara F. (ed.). 1992. Ethnologue: Languages of the world, 12th edition. Dallas, TX: Summer

Institute of Linguistics.

Grimes, Barbara F. (ed.). 1996. Ethnologue: Languages of the world, 13th edition. Dallas, TX: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

Grimes, Barbara F. (ed.). 2000. Ethnologue: Volume 1 Languages of the world, 14th edition. Dallas, TX: SIL International.

Harrisson, Tom. 1966. The unpublished Rennell M.S. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 39(1):102–103.

Lewis, M. Paul, Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the world, 16th edition. Dallas: SIL International.

Lewis, M. Paul, Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). 2013. Ethnologue: Languages of the world, 17th edition. Dallas: SIL International. http://www.ethnologue.com. (Accessed 19 June 2014.) Lobel, Jason William. 2013. Southwest Sabah revisited. Oceanic Linguistics 52(1).36–68.

Lobel, Jason. To appear. North Borneo sourcebook.

Pallesen, A. Kemp. 1985. Culture contact and language convergence. Manila: Linguistic Society of the Philippines.

Pullum, Geoffrey K. and William A. Ladusaw. 1996. Phonetic symbol guide. 2nd edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Reid, Lawrence A., ed. 1971. Philippine minor languages: Word lists and phonologies. (Oceanic Linguistics Special Publications No. 8.)

Schneeberger, W.F. 1937. A short vocabulary of the Banggi and Bajau languages. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 15(3):145–164.

Smith, Kenneth D. 1984. The languages of Sabah: A tentative lexicostatistical classification. Languages of Sabah: A survey report, edited by Julie K. King and John Wayne King, 1–49. (Pacific Linguistics, C-78.). Canberra: The Australian National University.

Talmy, Leonard. 2007. Lexical typologies. Language typology and syntactic description, vol. III: Grammatical categories and the lexicon, ed. Timothy Shopen, 66–168, 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Tarling, Nicholas. 1978. Sulu and Sabah: A study of British policy towards the Philippines and North Borneo from the late eighteenth century. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.