Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 20:32

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

The Effects of Unstructured Group Discussion on

Ethical Judgment

Clinton H. Richards & G. Stoney Alder

To cite this article: Clinton H. Richards & G. Stoney Alder (2014) The Effects of Unstructured Group Discussion on Ethical Judgment, Journal of Education for Business, 89:2, 98-102, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2013.768951

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2013.768951

Published online: 17 Jan 2014.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 75

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2013.768951

The Effects of Unstructured Group Discussion

on Ethical Judgment

Clinton H. Richards and G. Stoney Alder

University of Nevada Las Vegas, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA

The authors examine the effects of shared information and group discussion on ethical judgment when no structure is imposed on the discussion to encourage ethical considerations. Discussants were asked to identify arguments for and against a variety of business behaviors with ethical implications. A group moderator solicited and recorded arguments for and against the behaviors but provided no evaluation of the arguments presented or the behaviors described. Discussion group subjects were significantly less critical of profit-driven business behaviors than a control group, and were also less critical of self-interest-driven behaviors when those behaviors did not appear to adversely affect profits.

Keywords: discussion and ethics, ethical judgment, ethics education

Discussion has become an integral part of organizational decision making. It is also a major component of much of today’s business education. Some of this discussion occurs in the classroom, structured and led by an instructor, and some occurs outside the classroom without a designated leader. The latter may have a structure imposed upon it by a group assign-ment or it may occur informally among students with little or no structure imposed. Studies have shown that group discus-sion and decidiscus-sion making may significantly affect judgment (e.g., Sniezek & Henry, 1989; Suls & Miller, 1977), but the effects are not always positive. Group processes can also im-pair judgment and amplify the biases of members (Brauer & Judd, 1996; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974; Vroom & Yetton, 1973).

Discussion is a common component of the ethics train-ing occurrtrain-ing in both educational and business organiza-tions. Research suggests the discussion leader is a key to success. Numerous studies have found that a combination of ethical training and teacher-led discussion can be effec-tive in improving ethical decision making and promoting moral development (e.g., Harris & Guffey, 1991; Kavathat-zopoulos, 1993; Rest, 1986; Rest & Thoma, 1985). However, much of the discussion that occurs in and around businesses and educational institutions does not occur in the context of

Correspondence should be addressed to G. Stoney Alder, University of Nevada Las Vegas, Department of Management, Entrepreneurship, and Technology, 4505 Maryland Parkway, Box 456009, Las Vegas, NV 89154-6009, USA. E-mail: alders@unlv.nevada.edu

ethical training, nor is it structured in a manner that encour-ages consideration of ethical implications. Furthermore, a considerable amount of discussion is likely to occur infor-mally or at least away from the classroom and without a designated discussion leader. Despite its prevalence, how-ever, there is little research on the effects of leaderless group discussion outside of ethics training (Nichols & Day, 1982; O’Leary & Pangemanan, 2007) and virtually none on its ef-fects when the discussion is not structured in a manner that encourages ethical considerations. We seek to address this gap.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Nichols and Day (1982) and O’Leary and Pangemanan (2007) examined the effects of leaderless group discussion on group ethical decision making when that discussion oc-curred without ethics training. The former examined the effects when discussion was structured in a manner that encouraged ethical considerations, while the latter studied the effects of unstructured discussion. While Nichols and Day found leaderless but ethically structured discussion ap-peared to improve ethical decision making, O’Leary and Pangemanan found no evidence that unstructured discus-sion had a similar effect. Although these appear to sup-port the imsup-portance of an ethically structured discussion format with leaderless groups, the different student popu-lations sampled in the two studies may have also played a role.

GROUP DISCUSSION ON ETHICAL JUDGMENT 99

Subjects in Nichols and Day’s (1982) study were psy-chology students while those in O’Leary and Pangemanan’s (2007) were business students. Some critics have suggested that business education is likely to create a profit-centered bias by overemphasizing profit-related factors at the expense of other concerns (e.g., Ghoshal, 2005; Khurana, Nohria, & Penrice, 2005; Mitroff, 2004). If so, discussion might have been affected in the O’Leary and Pangemanan study because of the information students shared from previous business courses. Research suggests that shared information is likely to be repeated more often and weighed more heavily than unshared information (Kerr & Tindale, 2004). Any biases encouraged by the shared information are therefore expected to be amplified in discussion. Burton, Johnston, and Wilson (1991) reported no significant differences between the ethi-cal judgments of business students from a control group and those exposed to a short ethics training module that was fol-lowed by minimally structured group discussion. However, they suggested that the business education might have biased the discussions by encouraging a “vociferous pro-business stance” (Burton et al., 1991, p. 515) among some during the discussions.

PROBLEM STATEMENT

This study examines the effect of unstructured group dis-cussion on individual judgment when discussants share in-formation from previous training with a profit-centered bias. Discussion groups were large and thus required a moderator to encourage participation. However, the moderator took a neutral approach, encouraging a discussion of arguments for and against the behaviors described but not evaluating either the arguments or the described behaviors. Thus, our study parallels the kind of leaderless group discussions that fre-quently occur in business organizations and educational set-tings but have been neglected in the research. Additionally, the judgment task required subjects to indicate their approval or disapproval of the behaviors rather than their perceptions of the behaviors’ ethicality. In contrast to existing research, this framing of the task and the resulting lack of any imposed ethical structure correspond more closely with the frequent use of discussion in business organizations and classrooms to evaluate alternatives on multiple rather than just ethical criteria.

METHODOLOGY

Subjects and Shared Information

Subjects in the present study shared information from an introduction to business course that they were complet-ing. The course is taught in multiple sections using a pre-scribed textbook and chapters, and is a prerequisite to all other business core courses. An analysis of its content

re-veals the course’s emphasis on profit-related factors. Some ethical content is typically provided through a chapter on ethics and often the incorporation of some ethical mate-rial into other chapters as well, but many more pages are devoted to the pursuit of profit-related outcomes and even the chapter on ethics justifies ethical behavior in part by its presumed long-term positive effects on a firm’s prof-its. Selecting subjects who were completing an introduction to business course therefore provided a large sample with shared information emphasizing profit-related outcomes and practices.

Hypotheses

The emphasis on profit-related outcomes and practices in par-ticipants’ shared training is expected to result in the frequent use of this shared information in discussion to support the pursuit of profits, self-interest, and the described behaviors that appear to positively affect these outcomes. Discussants are also expected to weight this shared information more heavily than other information presented in the discussion when making postdiscussion judgments. We therefore pre-dict that unstructured group discussion will increase partic-ipants’ acceptance of ethically questionable behaviors de-signed to (a) increase profit-related outcomes or (b) further individual self-interest.

Measurement of Judgment

Judgment was measured using a scenario-based question-naire developed, validated, and used extensively by Harris (1990, 1991) and others to examine the ethical judgments of students and business professionals (e.g., see Harris & Guf-fey, 1991; Lopez, Rechner, & Olson-Buchanan, 2005; Ok-leshen & Hoyt, 1996; Richards & Corney, 2006; Richards, Gilbert, & Harris, 2002). The instrument measures judgment over 15 scenarios describing business practices involving co-ercion, deceit, fraud, influence dealing, and other self-interest or profit-centered behaviors. Participants indicated the extent to which they approved of each of the scenarios on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (approve) to 5 (disapprove;

α=.71). Although designed to measure ethical judgment, no

mention of the use of ethical criteria was made before admin-istration of the scenarios. Participants were merely told that they would be asked to evaluate each scenario and respond with their degree of approval or disapproval of the described actions.

Control and Discussion Groups

A total of 193 students enrolled in an introduction to busi-ness course at an urban U.S. university were administered the instrument during the last two weeks of the semester. Partic-ipants were assigned to either a control group (n=92) or a discussion group (n=101). Participants in the discussion group judged the behaviors described in the scenarios after

group discussion of each, while those in the control group completed the instrument without group discussion. Discus-sion group subjects were told the purpose of the discus-sion was to identify arguments for and against the described behaviors.

RESULTS

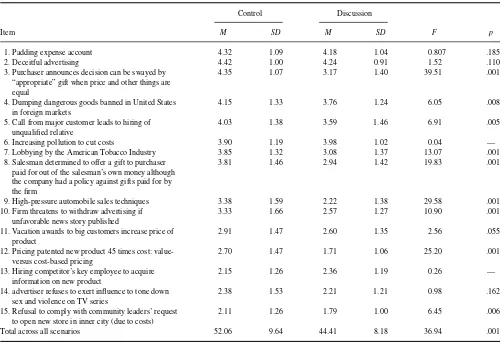

We tested the hypotheses that discussion would increase acceptance of ethically questionable behaviors designed to improve profit-related outcomes and those designed to further individual self-interest using analyses of variance models that controlled for the effects of gender and age. Because, previous research suggests gender and age may influence ethical decision making (Kohlberg, 1984; Lund, 2008; McCabe, Ingram, & Dato-on, 2006), we controlled for participants’ age and gender in all analyses. Results of these analyses are depicted in Table 1.

The 15 scenarios are described in Table 1 in the order of most disapproved to most approved by control partici-pants. Scenarios 1, 3, and 8 describe behaviors driven by the decision maker’s self-interest. The other 12 describe be-haviors driven by profit-related outcomes. ANOVA analy-sis of the judgment scores of discussion and control group participants summed over the 12 scenarios describing profit-driven behaviors found discussion group participants signifi-cantly less critical (Ms=34.14 and 39.87, respectively;p<

.001; standard error =.737 and .807). ANOVA analysis of judgment scores summed over the three scenarios describing self-interest–driven behaviors found a significant interaction between group and gender. However, separate analyses sug-gested discussion had significant effects on both men and women. Male discussion group members were significantly less critical than their counterparts in the control group (Ms=

9.21 and 12.50, respectively;p<.001; standard error=.427

and .365), while female discussion group members were significantly less critical than female control group mem-bers (Ms=11.29 and 12.77, respectively;p<.05; standard

error=.369 and .490).

Table 1 displays adjusted means from ANOVA analyses of group differences on each of the 15 scenarios and on total judgment scores summed over all the scenarios. Examination of the table reveals that discussion group participants were significantly more accepting (p <.05) on seven of the 12

scenarios describing profit-driven behaviors, and marginally significant on another (p <.10). Discussion group

partici-pants were also significantly more accepting (p<.05) on two

of the three scenarios describing self-interest–driven behav-iors. The only self-interest–driven behavior not viewed sig-nificantly more favorably by discussion group subjects was the one involving the padding of expense accounts, which clearly has a negative impact on profits. This suggests the hypothesis that discussion will increase acceptance of self-interest–driven behaviors should be qualified to include only those that do not appear to have a negative impact on profits.

DISCUSSION

Contributions and Direction for Future Research

Research exploring the relationship between group discus-sion and ethical decidiscus-sion making is increasingly important as concerns for business ethics grow, and as discussion be-comes an integral part of organizational and educational envi-ronments. Prior research has focused on ethically structured discussion or group ethical decision making. The relationship between unstructured discussion and individual judgment of the general acceptability (as opposed to ethical acceptabil-ity) of business practices with ethical implications has not been examined. The study reported here is a first step toward filling that gap. More research along these lines will further enhance our understanding of the effects of discussion on ethical decisions and behavior.

The results of this study demonstrate the adverse effect that such unstructured discussion can have on an individ-ual’s ethical decision making. Discussion among students exposed to shared training emphasizing profit-related factors increased their acceptance of ethically questionable profit and self-interest–driven business behaviors even when con-trol group subjects rated the behaviors negatively. This is cause for concern because this type of unstructured discus-sion is likely common in many organizations and educational institutions. If the shared information of discussants is too profit-centered, results of the present study suggest that the negative effects of that information bias are likely amplified by unstructured discussion.

Implications for Educators

Business educators are increasingly using group discussion in class as well as forcing discussion outside of it through group assignments. The present study suggests that such dis-cussions may adversely impact the ethical awareness and sensitivity of business students who share prior training that has a profit-centered bias. Educators involved in curricula that communicate such a bias therefore need to be particu-larly cautious of the use of unstructured discussion and par-ticularly adept at structuring discussion to encourage ethical as well as profit-oriented considerations.

It is encouraging that many business schools have at-tempted to expand the pool of shared information be-yond profit-centered considerations by offering ethics related courses and/or by incorporating ethics training into other courses in the curriculum. Considerable research suggests that business ethics and business and society courses often improve students’ ethical decision making (e.g., Abdolmo-hammadi & Reeves, 2003; Carlson & Burke, 1998; Eynon, Hill, & Stevens, 1997; Gautschi & Jones, 1998; Luther, Di-Battista, & Gautschi, 1997; Weber & Glyptis, 2000), but only about one in four offer an ethics-related course in the core (Abdolmohammadi & Reeves, 2003). The far more common approach is to rely on integrating ethics into other courses in

GROUP DISCUSSION ON ETHICAL JUDGMENT 101

TABLE 1

Adjusted Control and Discussion Group Means on Scenarios

Control Discussion

Item M SD M SD F p

1. Padding expense account 4.32 1.09 4.18 1.04 0.807 .185

2. Deceitful advertising 4.42 1.00 4.24 0.91 1.52 .110

3. Purchaser announces decision can be swayed by “appropriate” gift when price and other things are equal

4.35 1.07 3.17 1.40 39.51 .001

4. Dumping dangerous goods banned in United States in foreign markets

4.15 1.33 3.76 1.24 6.05 .008

5. Call from major customer leads to hiring of unqualified relative

4.03 1.38 3.59 1.46 6.91 .005

6. Increasing pollution to cut costs 3.90 1.19 3.98 1.02 0.04 —

7. Lobbying by the American Tobacco Industry 3.85 1.32 3.08 1.37 13.07 .001

8. Salesman determined to offer a gift to purchaser paid for out of the salesman’s own money although the company had a policy against gifts paid for by the firm

3.81 1.46 2.94 1.42 19.83 .001

9. High-pressure automobile sales techniques 3.38 1.59 2.22 1.38 29.58 .001

10. Firm threatens to withdraw advertising if unfavorable news story published

3.33 1.66 2.57 1.27 10.90 .001

11. Vacation awards to big customers increase price of product

2.91 1.47 2.60 1.35 2.56 .055

12. Pricing patented new product 45 times cost: value-versus cost-based pricing

2.70 1.47 1.71 1.06 25.20 .001

13. Hiring competitor’s key employee to acquire information on new product

2.15 1.26 2.36 1.19 0.26 —

14. advertiser refuses to exert influence to tone down sex and violence on TV series

2.38 1.53 2.21 1.21 0.98 .162

15. Refusal to comply with community leaders’ request to open new store in inner city (due to costs)

2.11 1.26 1.79 1.00 6.45 .006

Total across all scenarios 52.06 9.64 44.41 8.18 36.94 .001

Note. n=185. Scenario means could range from 1 (most favorable) to 5 (most disapproving). Analyses of variance controlled for age and gender. All significance levels are for one-tailed tests.df=2.

the curriculum. The effects of such integration are likely to be very transient (Richards, 1999) if not effectively imple-mented by a number of instructors in the curriculum. The fact that the integration approach appears to be favored at most business schools means more educators will need to display the motivation and develop the skills necessary to structure discussion appropriately whether leading it or not leading it. Because its effectiveness depends on the actions of ed-ucators teaching courses throughout the curriculum, the in-dividual instructor may find it difficult to ascertain the ex-tent of bias in the students’ shared training. We recommend instructors assume their students’ shared training has been biased, assure that discussion of issues with ethical impli-cations are structured to bring out ethical considerations, and incorporate other ethics training whenever possible prior to discussions so discussants will share that information as well as the more profit-centered information from their training. Instructors can provide an ethical structure to dis-cussion when he or she cannot lead it by assigning group projects that require ethical as well as other considerations

by the group or by assigning the role of a devil’s advo-cate to a student in each discussion group to voice ethical concerns.

CONCLUSION

It is hoped that the present study serves as a warning to educators who are concerned about their students’ ethics and who use discussion to reinforce learning in their classrooms. These educators may need to choose discussion topics and structure discussion in a manner that assures it frequently includes consideration of ethical issues, particularly when their students’ previous shared training has communicated a profit-centered bias. Because individual instructors have little control over the content and methodology of shared training outside their classrooms, an approach that decreases emphasis on profits in the curriculum by including a separate ethics-related course may be preferable to one that relies on each instructor to integrate ethics into their courses.

REFERENCES

Abdolmohammadi, M. J., & Reeves, M. F. (2003). Does group reason-ing improve ethical reasonreason-ing?Business and Society Review,108, 127– 137.

Brauer, M., & Judd, C. M. (1996). Group polarization and repeated attitude expressions: A new take on an old topic’ European Review of Social Psychology,7, 174–207.

Burton, S., Johnston, M. W., & Wilson, E. J. (1991). An experimental assessment of alternative teaching approaches for introducing business ethics to undergraduate business students.Journal of Business Ethics,10, 507–518.

Carlson, P. J., & Burke, F. (1998). Lessons learned from ethics in the class-room: Exploring student growth in flexibility, complexity and compre-hension.Journal of Business Ethics,17, 1179–1187.

Eynon, G., Hill, N. T., & Stevens, K. T. (1997). Factors that influence the moral reasoning abilities of accountants: Implications for universities and the profession.Journal of Business Ethics,16, 1297–1309.

Gautschi, F. H., III, & Jones, T. M. (1998). Enhancing the ability of busi-ness students to recognize ethical issues: An empirical assessment of the effectiveness of a course in business ethics.Journal of Business Ethics, 17, 205–216.

Ghoshal, S. (2005). Bad management theories are destroying good man-agement practices.Academy of Management Learning and Education,4, 75–91.

Harris, J. R. (1990). Ethical values of individuals at different levels in the organizational hierarchy of a single firm.Journal of Business Ethics,9, 741–750.

Harris, J. R. (1991). Ethical values and decision processes of business and non-business students: A four-group study.Journal of Legal Studies in Education,9, 215–220.

Harris, J. R., & Guffey, H. J. Jr. (1991). A measure of the short-term effects of ethical instruction.Journal of Marketing Education,13, 64– 68.

Kavathatzopoulos, I. (1993). Development of a cognitive skill in solving business ethics problems: The effect of instruction.Journal of Business Ethics,12, 379–386.

Kerr, N. L., & Tindale, R. S. (2004). Group performance and decision making.Annual Review of Psychology,55, 623–55.

Khurana, R., Nohria, N., & Penrice, D. (2005). Management as a profession. In J. W. Dorsch, A. Zelleke, & L. Berlowitz (Eds.),Restoring trust in American business(pp. 43–62). Cambridge, MA: American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Kohlberg, L. (1984).Essays on moral development. Volume II. The psychol-ogy of moral development. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Lopez, Y. P., Rechner, P. L., & Olson-Buchanan, J. B. (2005). Shaping ethical perceptions: An empirical assessment of the influence of business education, culture, and demographic factors.Journal of Business Ethics, 60, 341–358.

Lund, D. B. (2008). Gender differences in ethics judgment of marketing pro-fessionals in the United States.Journal of Business Ethics,77, 501–515. Luther, H. K., DiBattista, R. A., & Gautschi, T. (1997). Perception of what the ethical climate is and what it should be: The role of gender, academic status, and ethical education.Journal of Business Ethics,16, 205–217. McCabe, A. C., Ingram, R., & Dato-on, M. C. (2006). The business of ethics

and gender.Journal of Business Ethics,64, 101–116.

Mitroff, I. I. (2004). An open letter to the deans and faculties of American business schools.Journal of Business Ethics,54, 185–189.

Nichols, M., & Day, V. (1982). A comparison of moral reasoning of groups and individuals on the “Defining Issues Test.”Academy of Management Journal,25, 201–208.

O’Leary, C., & Pangemanan, G. (2007). The effect of groupwork on ethical decision-making of accountancy students.Journal of Business Ethics,75, 215–228

Okleshen, M., & Hoyt, R. (1996). A cross cultural comparison of ethical perspectives and decision approaches of business students: United States of America versus New Zealand.Journal of Business Ethics,15, 537–549. Rest, J. R. (1986).Oral development: Advances in research and theory. New

York, NY: Praeger.

Rest, J. R., & Thoma, S. J. (1985). Does moral education improve moral judgment? A meta-analysis of intervention studies using the defining issues test.Review of Educational Research,55, 319–352.

Richards, C. H. (1999). The transient effects of limited ethics training. Journal of Education for Business,74, 332–334.

Richards, C. H., & Corney, W. (2006). Private and public-sector ethics. Journal of Business and Economics Research,4, 35–41.

Richards, C. H., Gilbert, J., & Harris, J. R. (2002). Assessing ethics education needs in the MBA program.Teaching Business Ethics,6, 447–476. Sniezek, J. A., & Henry, R. A. (1989). Accuracy and confidence in group

judgment.Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes,43, 1–28.

Suls, J. M., & Miller, R. L. (1977).Social comparison processes: Theoretical and empirical perspectives. New York, NY: Halsted Press.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuris-tics and biases.Science,185, 1124–1130.

Vroom, V. H., & Yetton, P. W. (1973).Leadership and decision making. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Weber, J., & Glyptis, S. M. (2000). Measuring the impact of a business ethics course and community service experience on students’ values and opinions.Teaching Business Ethics,4, 341–358.