Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 17 January 2016, At: 23:33

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Signalling Creditworthiness: Land Titles, Banking

Practices, and Formal Credit In Indonesia

Paul Castañeda Dower & Elizabeth Potamites

To cite this article: Paul Castañeda Dower & Elizabeth Potamites (2014) Signalling

Creditworthiness: Land Titles, Banking Practices, and Formal Credit In Indonesia, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 50:3, 435-459, DOI: 10.1080/00074918.2014.980376

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2014.980376

Published online: 03 Dec 2014.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 154

View related articles

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, Vol. 50, No. 3, 2014: 435–59

ISSN 00074918 print/ISSN 14727234 online/14/00043526 © 2014 Indonesia Project ANU http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2014.980376

* We are grateful to a number of people for providing us with feedback about this project. We would like to thank Bill Easterly, Raquel Fernández, Daniel Gilligan, Sergei Guriev, Jon -athan Morduch, Debraj Ray, Mario Rizzo, Sergei Stepanov, and Katia Zhuravskaya. We are also grateful to the Social Science Research Council for providing funding for the ieldwork discussed in this article and to Bank Rakyat Indonesia for facilitating our meetings with local bankers. Castañeda Dower acknowledges the support of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation, grant No. 14.U04.31.0002, administered through the New Economic School’s Center for the Study of Diversity and Social Interactions. Any errors that remain are our own.

SIGNALLING CREDITWORTHINESS:

LAND TITLES, BANKING PRACTICES, AND

FORMAL CREDIT IN INDONESIA

Paul Castañeda Dower* Elizabeth Potamites*

New Economic School, Moscow Mathematica Policy Research

Many land titling programs worldwide have produced lacklustre results in terms of achieving access to credit for the poor. This may relect insuficient emphasis on lo

-cal banking practices. Bankers commonly seek to ensure repayment by using meth

-ods other than securing collateral, such as targeting borrower characteristics that, on average, improve repayment rates. Formal land titles can signal these important characteristics to the bank. Using a household survey from Indonesia, we provide evidence that formal land titles have a positive and signiicant effect on access to credit and that at least part of this effect is best interpreted as an improvement in information lows. These results stand in contrast to the prevailing notion that land titles function only as collateral. Analysts who neglect local banking practices may misinterpret the observed effect of systematic land titling programs on credit access because these programs tend to reduce the signalling value of formal land titles.

Keywords: land title, credit

JEL classiication: O12, O17, Q15

INTRODUCTION

What are the channels through which land titles could affect access to formal credit? The standard argument posits that formalising property rights equips landowners with collateral, opening up access to previously unavailable credit markets. In this article, we present evidence that formal land titles could also have an informational value by signalling creditworthiness to bankers. This evidence provides a richer understanding of how poor landowners gain access to credit, one of the main justiications for largescale land titling programs sponsored

by the World Bank and other aid organisations. The success of these programs depends on how local banking practices use formal land titles. When bankers use formal land titles other than as collateral, these programs may have unintended consequences. In particular, a systematic land titling program would likely elimi -nate the signalling value of possessing a formal land title.

In Indonesia, as in many developing countries, obtaining a formal title can be costly, lengthy, and bureaucratic.1 Therefore, having a formal land title can pro -vide information about unobservable characteristics, such as the landowner’s business acumen, their ability to interact within formal rules, the degree of their integration into formal markets, or the condition of their asset.2 A bank may pre -fer to lend to formally titled households, not only because the title mitigates the bank’s risk in the case of a default but also because the title provides exante infor -mation about the likelihood of compliance with the loan contract.

To assess the informational role of land titles, we use the 2002 Microinance Access and Services Survey (MASS). The MASS was conducted by Bank Rakyat Indonesia (BRI), a publicly owned commercial bank that has extensive experi -ence in microlending, in order to evaluate households’ microinance activity and potential new markets in rural and urban areas. The survey provides disaggre -gated data on household economic activities, assets, and loans for 1,438 house -holds in 72 villages and urban neighbourhoods across six provinces. Since not all borrowers with a land title use it as collateral, we can separately identify the effect on loan size of having a land title versus offering it as collateral. In fact, only 40% of those with a formal land title and a formal bank loan in the 2002 MASS used the title as collateral.3

We ind evidence for our explanation of formal land titles as information by considering irsttime borrowers. When dealing with borrowers who have had previous loans, banks have to some degree already solved their adverse selection

1. A title applicant usually requires a letter from the village head, verifying that the land is in the applicant’s possession. The applicant then needs to have a survey conducted, which involves funding the boundary markers, the survey fee, and all transportation costs. The document must then be veriied, mapped, and certiied. In total, the process can easily take one year. Once the applicant has the certiicate, they must pay a oneoff tax on the right to have a title on a piece of land. (This is not a property tax or a tax on the sale.) Anecdotal evi -dence reveals that applicants can also accumulate signiicant informal costs while obtaining a title. For example, the stated fee of a land certiicate is around Rp 300,000 (approximately

$33 in 2002). Yet when we asked our survey respondents what the actual fee was, their an

-swers ranged from Rp 1 million to Rp 2 million (approximately $111 to $222 in 2002). 2. Even if the land title has been inherited, possession of it increases the incentive to learn how to interact in the formal sector.

3. The other 60% is made up mainly of salary guarantees, but it also includes other in

-formal land documents, vehicle ownership certiicates, or even no security at all. Of all irsttime borrowers with a land title, 42% offered it as collateral. The relatively low us -age of land title to secure a loan could relect the poor state of land registration overall.

Since the 2002 MASS, the Indonesian government has taken initiatives, such as Regula

-tion 24/2007, to improve land titling (Bappenas 2012). With these initiatives, the use of land title for securing a loan could have changed. However, a recent World Bank report evaluating its latest land administration project, lasting from 2000 to 2009, inds mixed results (World Bank 2014), indicating that there is room for improvement and suggesting that our indings are still valid in 2014.

Signalling Creditworthiness: Land Titles, Banking Practices, and Formal Credit 437

problem. In a study of the inancial evolution of irms in Indonesia, McLeod (1991) demonstrates that more established irms do indeed have better access to credit.4 Thus, if a formal land title has a signalling role, we would expect that it should be present for borrowers without established credit histories. Our indings conirm that irsttime borrowers beneit from merely possessing a land title, irrespective of whether they offer it as collateral. The same is not true for all formal bank bor -rowers, for whom possession alone does little to increase access to credit. It is offering a land title as collateral as opposed to other ways of securing a loan that is associated with an increase in loan size.

We provide supplemental support for the informational role of land titles in Indonesia’s smallscale credit market by discussing the results of a mail survey of BRI unit heads that we conducted in 2004. Our mail survey and ield observations conirm that BRI unit banks use means other than securing collateral in seeking to ensure repayment of the relatively small loans that we are considering. Moreover, bankers report that the legal process of foreclosing or collecting on collateral is too costly for oneoff relationships. In fact, even oficially registering the collateral may be prohibitively costly.5

Since land titles can also affect credit demand, observed differences between irsttime and repeat borrowers could relect the impact of land titles on credit demand. We address this issue by taking advantage of two unique features of the 2002 MASS. First, the survey asked respondents if they had recently been rejected for a loan from a formal bank and for what amount they had applied. In other words, we have the actual amount demanded at the going interest rate for these rejected loan applicants. Second, for each questionnaire, a trained loan oficer evaluated whether the respondent household would be feasible to lend to, according to BRI’s interestrate menu. We use this feasibility measure to predict whether the household had recently been rejected for a loan, which is independent of household credit demand. We then use the predicted probability of rejection, which allows us to identify how land titles affect household credit demand. We ind that land titles show no statistical relationship with demanded loan amounts. In addition, we generate household credit demand for all formal bank borrowers using this rejection probability and, after controlling for our measure of credit demand, ind that the main results are unaffected.

The group of households that accessed or tried to access institutional lending is not random, and we cannot claim that these results indicate the relative impor -tance of a land title’s signalling role for nonborrowers (some of whom may have been excluded from formal credit because of their lack of adequate collateral). We explore the relation between land titles and having had a formal bank loan and ind that land titles are also correlated with participation in formal credit. Based on the assumption that a household’s distance to the nearest formal bank should affect participation but not loan size, we are able to correct for this selection

4. McLeod (1991) also argues that expanding credit access as a irm evolves is a socially optimal strategy for lenders, owing to the risk that irsttime borrowers present.

5. Other factors can arise that undermine the possibility of a legal transfer if the borrower defaults: weak legal infrastructure, political pressure, and a thin land market. See Domeher

and Abdulai’s (2012) study for a discussion of why land registration may not have a posi

-tive impact on credit access.

problem—we ind that accounting for the likelihood of having had a formal bank loan only strengthens our main result. Thus, the main contribution of this article is that we establish an additional important role that formal land titles play in the credit market. Land titles can support and develop the credit market by improv -ing the low of information. Namely, formal land titles reveal dificulttoobserve applicant characteristics to resourceful bankers. The signalling value of land titles helps explain some recent indings, such as those of Galiani and Schargrodsky (2010) that households newly titled as a result of a titling program do not have bet -ter access to credit. Systematically distributed land titles lack the information com -ponent of sporadically obtained ones.6 Hence, incorporating banking practices into the analysis is necessary to understand the effect of land titles on access to credit.

PREVIOUS LITERATURE

The positive effect of formal land titles on access to credit is purported by Dei -ninger and Binswanger (1999) to be well established. Nevertheless, we observe mixed results in our survey of the literature. Table 1 lists previous empirical work on how land titles affect access to formal bank credit. The irst three columns cor -respond to the study, the region of study, and the empirical results for whether having a land title improved credit access. In addition, some studies consider systematic titling programs in which possessing a land title can be viewed as relatively exogenous to the credit decision, while others, as is the case in this arti -cle, study ’sporadic‘ (or individually obtained) titles, endogenously determined (shown in the fourth column). The results reported vary considerably, relecting that these studies took place in different countries with different sets of institu -tions governing the credit and land markets, and, in particular, under different banking practices. While table 1 consists of demandside studies, there is also evidence from the supply side. For example, Domeher (2012), who surveys credit oficers in Ghana, inds little to no additional beneit of land registration provided that some type of land documentation exists.

Measuring the effect of possession of a land title on access to formal credit requires separating the effects of land title on the supply of formal credit from the effects on the demand for credit. Most studies simply assume that there exists excess demand for formal credit.7 Feder et al.’s (1988) study lets observed credit equal the minimum of supplied credit and credit demanded but then resorts to assuming excess demand in the empirical work. The evidence of Johnston and

6. On a more positive note, this argument could suggest that even nontransferable rights of exclusion to land might positively inluence credit access if the process for receiving these documents is not automatic. These types of rights are often granted instead of fully transferable land rights when governments are worried that the formalisation of property rights will make it more likely for smallscale farmers to lose their land. This practice has been used in India.

7. Kochar (1997) argues that the existence of informal credit markets may cause the empir

-ical data to misrepresent the extent of credit rationing: institutional credit may be accessed

less, because individuals’ demand for credit may be satisied by the informal sector. More

-over, McLeod (1991) points out that credit constraints are actually the reverse of what is often assumed—that is, it is institutional credit that lacks access to smallscale borrowers, because institutions often cannot compete with informal sources of credit.

TABLE 1 Previous Literature on the Effect of Land Titles on Access to Formal Bank Credit

Study Region Positive signiicant effect? Program

Feder et al. 1988 Rural Thailand Yes, especially in markets with welldeveloped credit markets Sporadic

Lopéz 1996 Honduras Yes Systematic

Place & MigotAdholla 1998 Ghana, Rwanda, & Kenya No Both

Pender & Kerr 1999 Rural India No Sporadic

Broegaard, Heltberg, &

MalchowMøller 2002 Nicaragua No Both

Carter & Olinto 2003 Paraguay No, except for large landowners Sporadic

Field & Torero 2004 Urban Peru Yes, for public bank loans; no, for private loans (though it

did lower interest rates) Systematic

Foltz 2004 Tunisia Yes Both

Boucher, Barham, & Carter 2005 Honduras & Nicaragua No Systematic

Do & Iyer 2008 Vietnam No Systematic

Boucher, Guirkinger, & Trivelli 2009 Rural Peru Yes, a title reduces the probability of being credit constrained Both

Petracco & Pender 2009 Uganda No, for title; yes, for freehold tenure Sporadic

Galiani & Schargrodsky 2010 Argentina Yes, but modest Systematic

Morduch’s (2008) study, based on the 2002 MASS, convinces us that excess demand is not an appropriate assumption for the households in our sample. We address this problem by using information about the demand of those who have had loan applications rejected, combined with measures of hypothetical supply. In contrast, Field and Torero (2004) take advantage of the timing of the implementation of a systematic titling program. Using matching on observables to difference out demand, they measure the effect of land title on credit access only among banks that require title. We cannot employ this method, because a systematic land titling program did not occur during the period of analysis in the areas that we study.

In general, the endogeneity of land title is a dificult problem to solve. In the literature, the primary method of tackling endogenous land titles is to exploit a systematic titling program. In light of the argument in this article, this identiica -tion method risks missing any direct effect of using land titles as informa-tion. Although one could argue that titling programs often fail to produce full com -pliance, giving scope for an information effect, there are two reasons why this approach is unsatisfactory. First, the signal is likely to be much noisier (owing to the time and cost subsidies of the program implementers) than in the sporadic setting. Second, faced with imperfect compliance the econometrician identiies the average treatment effect of title only under strong assumptions. The other common approach, of using instrumental variables, is also problematic, since the signal is correlated with unobservables. We prefer to take a targeted approach to endogeneity. We imperfectly address it by employing subdistrict ixed effects, which should allay concerns about spurious correlation at the subdistrict level, and a variable that accounts for differences in the supply of informal credit at the village and urban neighbourhood level. We also present instrumental variables estimates to verify the noeffect prediction of the signalling hypothesis. While we believe that our evidence is persuasive, we cannot claim to identify a causal effect of land title on information lows.

Finally, we should express a word of caution about the importance of social networks in credit markets. Hoff, Braverman, and Stiglitz (1993) argue that titling systems can possibly have a beneicial role only in areas where land markets mat -ter and where land rights are not well established by the community. Lanjouw and Levy (2002) show that strong community relationships in urban areas of Ecuador can function as well as formal claims on assets. Hence, having a land title could substitute for social networks that are dificult to observe. Nevertheless, it may not be effective to rely on social networks for enforcing claims on assets in collateral arrangements with a formal bank.

CREDIT-MARKET SETTING AND BANKING PRACTICES IN INDONESIA

Indonesia has an extensive rural banking system, supplied mostly by BRI, the bank most central to our study. In 2004, BRI was the fourthlargest bank in Indo -nesia, with approximately 10% of market share as measured by the total assets held by banks. The BRI unit is the part of the bank that deals with smaller loans.8

8. On a relative scale, institutions that focus on microlending were affected less drasti -cally by the 1997–98 Asian inancial crisis than those that did not. In fact, BRI units were proitable throughout the crisis and it is reported that BRI units subsidised the branch banks during and after the crisis (Patten, Rosengard, and Johnston 2001; Rosengard et al. 2007).

Signalling Creditworthiness: Land Titles, Banking Practices, and Formal Credit 441

It has more than 4,000 ofices, reaching roughly a third of all households in Indo -nesia.9 In general, BRI units attempt to reach a part of the population that may not have had the opportunity to participate in the formal inancial sector. As such, the competitiveness (or the lack thereof) of this market must be kept in mind for policy analysis. In the MASS, more than 80% of formal bank loans were from BRI units.

We conducted a mail survey of 192 BRI units across the same six provinces and 12 districts in which the MASS was conducted. Our response rate was above 60%. Most of the surveys were answered directly by the unit manager. We do not use this novel dataset in the regression analysis, however, because unit manag -ers move around quite frequently, so there is no way to match reported banking practices to geographical locations. Instead, these data inform our interpretation of the empirical results.

In our mail sample, on average only 42% of loans that were collateralised were done so with a land title certiicate. However, almost 40% of all loans were not col -lateralised; instead they were guaranteed by deductions from future salary (ixed income). This is similar to what was found in the MASS, in which 33% of the 326 loans recorded at BRI units or branches were collateralised by a formal land title. Our survey asked if having a land title would increase the likelihood of success for a loan application. The answer was yes for 60% of our sample, though only 29% said that an applicant with a formal land title would have more chance of receiving a higher loan amount than someone without a title (holding all other factors constant).

Instead of relying solely on securing formal collateral, BRI units use other methods to ensure repayment. These methods rely on an applicant’s reputation or lending within social networks to bolster group monitoring, in order to solve both exante adverse selection and expost moral hazard problems.10 The BRI approach allows discretion within a set of basic rules. For example, loans above a certain limit, typically around Rp 20 million (approximately $2,200 in 2002), must be approved by a regional BRI branch, but at the unit level there is no one formula for accepting or rejecting loan applicants. Unit managers are allowed to rely on notions such as ‘trustworthiness’ when granting a loan.11 Unit manag -ers are also encouraged to raise repayment rates by using progressive lending, whereby the lender makes larger amounts of credit available after each successful repaid loan; interest refunds, whereby the lender gives a rebate on interestrate payments if the borrower pays the loan on time; and social networks, whereby the lender relies on borrowers in the same social network to encourage repay -ment. Successful unit managers are granted greater discretion and higher limits for lending without branch approval. When asked to assess the most important

9. BRI has been studied in the microinance literature. For more information on the history and practices of BRI, see Maurer’s (1999) study.

10. See Morduch’s (1999) study for a thorough review of these methods, which are com

-monly used in the microinance world.

11. Consider, for example, the following method, which is often used: the loan applicant ills out a description of the condition of their assets, and then the BRI unit manager sends a bank employee to view the assets in order to make a comparison. What the bank cares about is not just the value of assets but also whether the description of the assets was honest.

factor in considering whether to grant a loan, 82% of respondents indicated the character of the individual. When determining the likelihood of repayment of the applicant (which determines the loan size for which the applicant is eligible), the most important factors were cash low (66%) and character (20%). Only one respondent indicated that collateral was the most important factor for determin -ing repayment capacity, and none indicated that collateral was the most important factor in considering whether to grant a loan. This suggests that unit managers are aware of the informational problem and that they take personal characteristics (including the past relationship with the bank) into account in the loan decision, as opposed to relying solely on securing collateral to align incentives ex post.

Repayment rates are very high in the BRI units, above 95% in most areas (Pat -ten, Rosengard, and Johnston 2001). BRI prefers to avoid using foreclosure to enforce repayment. Foreclosure is described as a very rare event anecdotally, but our survey indicates that it does happen; 37% of unit managers report having foreclosed on a client at least once.12 Since the legal cost of foreclosure is high,

we would instead expect to see forced or encouraged sales of pledged assets. In our survey, 77% of respondents said that they had encouraged clients, at some point in the past year, to sell collateral in order to repay their loan. The existence of encouraged sales of clients’ assets may indicate that the asset is not fully trans -ferable in case of default. BRI and other banks in Indonesia accept, as collateral, informal land documents that demonstrate ownership but are not legally trans -ferable. Moreover, for individual BRI units the cost of registering a formal land title as collateral may outweigh its possible beneits, suggesting again that banks nominally make use of collateral.

The BRI unit’s reliance on having personal relationships with clients also could make borrowing more dificult for new clients. For instance, when asked how new clients ind out about BRI and its services, 88% of the bankers said it was through friends and family. We also enquired about the maximum loan size avail -able to clients without a formal land document. We ind, on average, that old clients would be eligible for Rp 5 million more than new clients, a difference that is the average value of a loan at BRI units. New clients without formal land docu -ments thus face tighter credit constraints and are less likely to take advantage of BRI’s services unless they already know others who do so.

In sum, the results from our survey are consistent with the idea that having a formal land title signals useful information to the bank, especially if the titled household is a new borrower. In general, banks use methods other than securing formal collateral to solve moral hazard and adverse selection problems, and BRI units provide a good description of how this works. These methods often empha -sise the personal relationship between the bank and client, possibly making it

12. This number seems large, leading us to believe that managers have included threats to foreclose. Formal foreclosure is rare in Indonesia’s smallscale loan market. However, just because foreclosure is not observed does not mean that collateral is not at work. A simple

gametheoretic framework yields a Nash equilibrium where no one defaults yet the pos

-sibility of foreclosure is real. In the Indonesian context, this is probably not the equilibrium. Borrowers rather than lenders are generally favoured. Foreclosure is a socially sensitive issue, and the legal practice of foreclosure in Indonesia is unpredictable and lengthy. These high costs of foreclosure most likely are at the expense of the borrowers, and streamlining the process could beneit all parties involved.

Signalling Creditworthiness: Land Titles, Banking Practices, and Formal Credit 443

more dificult for irsttime borrowers. As a signal of borrower characteristics, land titles can substitute for a history of successful repayment.

DATA USED FOR THE REGRESSION ANALYSIS

For the regression analysis in this article, we use data from two sources. Our main source is BRI’s 2002 MASS. We also have additional villagelevel and urban neighbourhoodlevel information from the 2003 round of Statistik Potensi Desa (Podes), a survey of local leaders, conducted annually by the Indonesian govern -ment.13

The 2002 MASS

The 2002 MASS consisted of more than 1,438 households across 72 different vil -lages (desa) and urban neighbourhoods (kelurahan) in West Java, East Java, West

Kalimantan, East Kalimantan, North Sulawesi, and Papua.14 For each of the six provinces, two districts (kabupaten for rural districts and kotamadya for urban dis-tricts) were selected. For each district, three subdistricts were randomly selected (kecamatan). For each of these subdistricts, two villages or urban neighbourhoods

were selected at random. Finally, respondents of these localities were randomly chosen using local censuses. Thus, the survey covered both customers and non customers of BRI, and 58% of respondents lived in rural districts. It slightly over -sampled poor households, in both urban and rural areas (Johnston and Morduch 2008). We exclude the landless from all results that we present.

Twothirds of the respondent households had a business enterprise, and nearly half of these twothirds worked in the agricultural sector. Thus, one should not equate land parcels with agricultural plots, although lowerincome and rural households are more likely to use land parcels for agricultural production. For households that had multiple land parcels, we label them as titled if any of their land was titled.15 Most of our sample had more than 80% of their total land value either formally titled or informally documented, and only 53 households reported no documentation at all. Land documents other than formal land titles refer to land deeds, customary or traditional land documents, and tax receipts. In general, titled households are less common in rural areas (29%) than in urban areas (65%).

In 2004, out of the 80 million land parcels on the iscal tax register, less than 27 million were on the legally titled register and about 1.3 million new titles were registered sporadically. The total number of land parcels was estimated to be growing by more than 1 million per year (World Bank 2004, 5). The current system of titling should be understood in the context of how land rights have

13. Statistik Potensi Desa (Podes) stands for Village Potential Statistics, a villagelevel and urbanneighbourhoodlevel economic census. We use the 2003 census, which was collected in 2002.

14. In 2002, Papua included the yettobeformed province of West Papua. In West Java, all sampled households were rural.

15. We could instead use the fraction of the value of the household’s total land assets that are titled. In practice, this distinction is almost irrelevant in our dataset; even though 352 of our households report having more than one plot, all but 57 of these households have all their plots either titled or untitled.

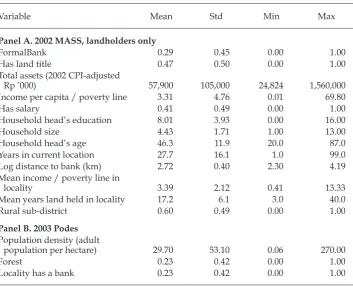

TABLE 2 Summary Statistics

Variable Mean Std Min Max

Panel A. 2002 MASS, landholders only

FormalBank 0.29 0.45 0.00 1.00

Has land title 0.47 0.50 0.00 1.00

Total assets (2002 CPIadjusted

Rp ’000) 57,900 105,000 24,824 1,560,000

Income per capita / poverty line 3.31 4.76 0.01 69.80

Has salary 0.41 0.49 0.00 1.00

Household head’s education 8.01 3.93 0.00 16.00

Household size 4.43 1.71 1.00 13.00

Household head’s age 46.3 11.9 20.0 87.0

Years in current location 27.7 16.1 1.0 99.0

Log distance to bank (km) 2.72 0.40 2.30 4.19

Mean income / poverty line in

locality 3.39 2.12 0.41 13.33

Mean years land held in locality 17.2 6.1 3.0 40.0

Rural subdistrict 0.60 0.49 0.00 1.00

Panel B. 2003 Podes

Population density (adult

population per hectare) 29.70 53.10 0.06 270.00

Forest 0.23 0.42 0.00 1.00

Locality has a bank 0.23 0.42 0.00 1.00

Note: Observations in panel A = 1,287; in panel B = 72. FormalBank = 1 if the household reported having had a formal loan. Forest = 1 if the settlement is near a forested area. MASS = Bank Rakyat Indonesia’s Microinance Access and Services Survey. Podes = Statistik Potensi Desa (Village Potential Statistics survey).

been established previously, especially in areas where adat (traditional) law is still

respected. Evidence of ownership can come in a variety of forms. The most for -mal of these infor-mal rights to land is a land deed, or akte, which represents the purchase of a piece of land and is oficially stamped and notarised. A less formal but perhaps locally stronger right is the girik or petok, which is a use claim on land

and comes from customary law. Documents known as Letter C or D are certi -ied by the village leader and can be inherited. In the MASS, land parcels with formal land titles are slightly overrepresented (45% of land parcels have formal land titles; 12% have an akte; 21% have a girik, petok, or Letter C or D; and 10%

have only tax receipts to demonstrate ownership). In our sample, very few house -holds—only 4% of landowners—had no documents at all.

Table 2 gives the summary statistics for the covariates that we include in our estimations. The variable ‘FormalBank’ equals one if the household reported ever having had a formal loan. The per capita household income is divided by the local poverty line. The local poverty line varies by province and, within each province, there are separate poverty lines for rural and urban areas.

We have data on 405 distinct formal loans made to 374 different households. On average, formal bank loans are signiicantly larger than loans from other

Signalling Creditworthiness: Land Titles, Banking Practices, and Formal Credit 445

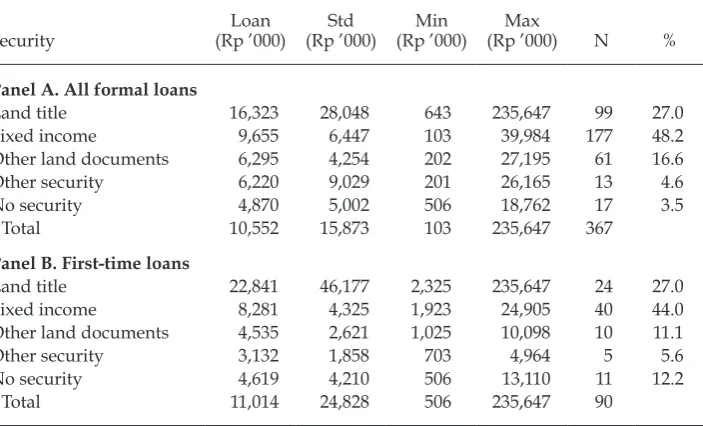

TABLE 3 Average Formal Loan Amounts, by Type of Security Offered

Security (Rp ’000)Loan (Rp ’000)Std (Rp ’000)Min (Rp ’000)Max N %

Panel A. All formal loans

Land title 16,323 28,048 643 235,647 99 27.0

Fixed income 9,655 6,447 103 39,984 177 48.2

Other land documents 6,295 4,254 202 27,195 61 16.6

Other security 6,220 9,029 201 26,165 13 4.6

No security 4,870 5,002 506 18,762 17 3.5

Total 10,552 15,873 103 235,647 367

Panel B. First-time loans

Land title 22,841 46,177 2,325 235,647 24 27.0

Fixed income 8,281 4,325 1,923 24,905 40 44.0

Other land documents 4,535 2,621 1,025 10,098 10 11.1

Other security 3,132 1,858 703 4,964 5 5.6

No security 4,619 4,210 506 13,110 11 12.2

Total 11,014 24,828 506 235,647 90

Source: Data from Bank Rakyat Indonesia’s Microinance Access and Services Survey, 2002.

Note: Amounts adjusted by the consumer price index, using 2002 as the base year. N = observations.

sources and most (74%) reported loans are formal.16 Because our loan amounts are from different years, with most loans having been granted in 1998–2002 (only 9% of the formal loans are from earlier), just after the 1997–98 Asian inancial crisis, we normalised the loan amounts by converting them to rupiah, adjusted to the consumer price index (CPI), and used 2002 as the base year.17 Convert -ing to CPIadjusted loan amounts leads to 38 fewer loans—31 because of miss-ing loan dates and 7 because of other missing data.18 Table 3 breaks down the formal loan amounts by the type of security offered. Of the formal loans reported with complete data, 90 went to households for whom this was their irst loan. In both rural and urban areas, titled households had more formal loans—40% of titled households had had a formal bank loan compared with only 20% of other land documented households—and loans securitised by formal land titles tended to

16. In our data, we have 680 distinct loans, 489 of which are from formal banks. Of these formal loans, 475 report information on how the loan was secured. The difference between 475 and 405 can be explained by our excluding the landless from our analysis. Nonformal loans consist of microbank loans (14%) and informal sources (12%).

17. The Indonesian CPI is available from Badan Pusat Statistik, the central statistics agency: http://www.bps.go.id/eng/aboutus.php?inlasi=1. Over the range of years in which the formal loans were given, there were three changes to the weighting of the CPI and to the sample of cities included in the costofliving surveys. To account for these changes, we have run robustness checks for our main results by including dummies for urban and rural CPIweighting groups. The results are similar.

18. We dropped one loansize observation because of its unrealistic loan amount of Rp 1,000 (less than $1).

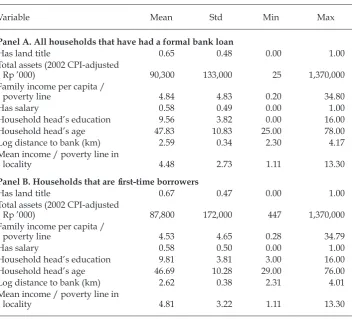

Variable Mean Std Min Max

Panel A. All households that have had a formal bank loan

Has land title 0.65 0.48 0.00 1.00

Total assets (2002 CPIadjusted

Rp ’000) 90,300 133,000 25 1,370,000

Family income per capita /

poverty line 4.84 4.83 0.20 34.80

Has salary 0.58 0.49 0.00 1.00

Household head’s education 9.56 3.82 0.00 16.00

Household head’s age 47.83 10.83 25.00 78.00

Log distance to bank (km) 2.59 0.34 2.30 4.17

Mean income / poverty line in

locality 4.48 2.73 1.11 13.30

Panel B. Households that are irst-time borrowers

Has land title 0.67 0.47 0.00 1.00

Total assets (2002 CPIadjusted

Rp ’000) 87,800 172,000 447 1,370,000

Family income per capita /

poverty line 4.53 4.65 0.28 34.79

Has salary 0.58 0.50 0.00 1.00

Household head’s education 9.81 3.81 3.00 16.00

Household head’s age 46.69 10.28 29.00 76.00

Log distance to bank (km) 2.62 0.38 2.31 4.01

Mean income / poverty line in

locality 4.81 3.22 1.11 13.30

Source: Data from Bank Rakyat Indonesia’s Microinance Access and Services Survey, 2002.

Note: We exclude the landless. Observations in panel A = 336; in panel B = 90.

TABLE 5 Distribution of Control Variables for Households That Have Applied for a Loan

Status Assets Income Education Titled

Rejected 17.20* 3.30* 7.75* 0.58

Accepted 17.74* 4.40* 9.72* 0.64

Source: Data from Bank Rakyat Indonesia’s Microinance Access and Services Survey, 2002.

Note: Assets in logs of rupiah (adjusted by the consumer price index). Income relative to the poverty line. Education is in years of schooling. We exclude the landless.

* p < 0.05.

Signalling Creditworthiness: Land Titles, Banking Practices, and Formal Credit 447

be larger, on average. Firsttime borrowers used the same types of securities and offered them in roughly the same proportion as the general population of borrow -ers. In addition, conditional on having a formal loan, titled households and other documented households were equally likely to offer some type of land document as collateral (about 40% of the time).19 Since all documented households were equally likely to offer some type of land document, we infer that the relative ben -eit of offering a land document is similar to offering other forms of security. That is to say, if the only effect of a formal land title is as a better source of collateral, we would expect titled households to have used their land document comparatively more often.

Table 4 describes in more detail the characteristics of the subset of our sample that we are particularly interested in. Panel A gives the most important house -hold and localitylevel characteristics for all house-holds that have had a formal bank loan. Panel B looks at the same characteristics for households that are irst time borrowers. There are no signiicant differences between irsttime and repeat borrowers in any of these observable characteristics.20 Therefore, any difference between a bank’s relationship with a irsttime borrower and its relationship with a repeat borrower cannot be attributed to differences that are observable to the econometrician.

Selection into the formal loan market is a different story. Table 5 shows the distribution of the control variables for rejected applicants. In the MASS, 67 land -owning households reported having recently had a loan application rejected. These households tended to have fewer assets and less income and education. The MASS data also permits constructing hypothetical loan demand and sup -ply, with which we can address endogeneity. The survey was conducted by BRI loan oficers who worked in different geographical areas from those surveyed. The oficers were asked to privately judge how feasible it would be to extend a loan to the household that they had just surveyed. They reported whether they would grant the household a loan and what the maximum loan size would be and under what terms. These questions give us a measure of hypothetical supply. That is, without considering the effects of title on credit demand, we can evaluate whether a formal land title affects the amount of credit for which a household is hypothetically eligible. That these questions were answered by BRI loan oficers adds to their validity as a measure of credit supply. In general, the average maxi -mal feasible loan amount was almost Rp 8 million (roughly $890 in 2002), compa -rable to actual loan amounts; but of the 901 households that were attributed with a feasibility judgment, 565 had never had a formal bank loan. The MASS also asked households how much credit they would hypothetically be interested in obtaining if they had not applied for a formal bank loan. More than half of those with no previous bank loans claimed that they had never applied, because they

19. More than half of all formal loans did not use any type of land document. Instead, the most commonly cited security was an advance against future salaries, such as ixed income or the use of a guarantor.

20. We tested all continuous variables by applying both the conventional t-test (allowing

for the variances between the samples to differ) and the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test. We used a test of proportionality for all binary variables. There were no signii -cant differences at the 10% level.

did not want to be in debt. They were then asked a hypothetical question about their possible desired loan amount. However, this measure of demand is prob -lematic; even after giving a hypothetical loan amount, more than 80% insisted that they had no intention of borrowing formally. Their most common reason, given by 44%, was that they were concerned about repayment. Those that were titled were equally likely to be worried about repayment as those that were not.

The 2003 Podes

Panel B of table 2 gives some summary statistics for the localitylevel covariates from the Podes dataset that we include in our estimations. We have calculated these statistics by using only the villages and urban neighbourhoods in BRI’s MASS sample. They are roughly comparable to the full census. We will take one instrumental variable from Podes, the forestedarea dummy (‘Forest’). The National Land Agency (Badan Pertanahan Nasional) grants titles only to non forested land.21 The ‘Forest’ dummy equals one if the settlement is near a for -ested area. The proximity to forest land should be negatively correlated with the extent of titling. Since forest land is not under the jurisdiction of the agency, land titles cannot be issued for any plots under the oficial forestedland designation. A large amount of deforestation has occurred in Indonesia, and many plots have been cleared for some time but have not been unmarked as forest land. Settle -ments near forest land are more likely to contain plots that are cleared but are still oficially designated as forest land. Indeed, 28% of respondent households in the 2003 Podes were titled in settlements near forested areas, while 53% were titled in nonforested areas. The ‘Forest’ dummy does not predict the hypothetical desired loan amounts discussed above.

EMPIRICAL STRATEGY AND RESULTS

The key question and the main contribution of this article is to evaluate whether having a formal title inluences the size of observed formal loans, and, if so, to determine whether this is purely an effect of formal land titles being better col -lateral or whether they also have a signalling value. We will irst consider how possessing a formal land title affects loan amounts, while controlling for other observable variables that might also inluence credit access. We then control for whether a land title was offered to secure the loan, to see if simply possessing a land title is suficient. Next, we test whether the effect of possessing a land title is important for irsttime borrowers, since the signalling effect should be the strongest for this group. Equation (1) gives the econometric speciication for the preferred empirical test:

yi=α+γ1Ti+γ2Fi+γ3T⋅Fi+γ4Ci+Xiβ+Ei (1)

where yi , the outcome of interest, is the most recent loan amount obtained from

a formal bank in household i; Ti is an indicator variable of whether household i

21. Land that has been designated as forest (roughly 60% of land area) is handled by the Ministry of Forestry.

Signalling Creditworthiness: Land Titles, Banking Practices, and Formal Credit 449

has a formal title; Ci is whether the household used a formal title as collateral; Fi

is an indicator of whether the household is a irsttime borrower; and Xi consists

of both household covariates and locality and subdistrictlevel covariates.22 The idiosyncratic error term is denoted by Ei. We use clustered robust standard errors

at the subdistrict level, allowing for correlation within subdistricts, because the BRI unit lending area is roughly a subdistrict and the BRI framework grants con -siderable discretion to unit managers.

In equation (1), three effects are important to the signalling story: (a) γ1, which represents the effect of merely possessing a land title for repeat borrowers; (b) γ1+ γ3, which represents the effect of merely possessing a land title for irsttime bor -rowers; and (c) γ3, which tells us whether possessing a land title but not offering it as collateral is different for irsttime borrowers than for repeat borrowers. We reject the hypothesis that a land title functions only as collateral if γ3 is statistically different from zero, no matter whether we control for a land title being used to secure a loan, or when γ1+γ3 is statistically different from zero if we control for offering a land title as security. We note that if both γ1and γ3 are not statistically different from zero, we cannot reject the signalling hypothesis. Owing to the high cost of formally securitising these small loans with a land title, one could argue that offering a land title as security has some informational content.

In order to interpret equation (1) as a supplyside effect, we should assume that for borrowing households the supply constraint is binding, which is a common assumption in developing markets. Under this assumption, loan size is a good indicator of access to credit, since most households that apply for loans would demand more than they would eventually receive. One criticism of this approach is that some households may demand larger loan amounts than others. However, even if titled households, on average, were to demand higher loan amounts, the only ways that actual loan amounts would be higher are if the supply constraint were slack or if the bank relaxed the supply constraint because of the presence of a land title. The latter case is included in the effect of having a land title, and the assumption of the binding supply constraint rules out the former case. In ‘Assess -ing the Role of Credit Demand’, below, we more carefully explore this assumption by investigating whether the correlation between land titles and credit demand could explain the results (that is, that the supply constraint is not binding).

While we need to address the endogeneity of the land title variable, we also want to capture the signalling effect, which by its nature implies that land titles are correlated with unobservable variables that affect credit access (in particular, personal characteristics of the borrower that are desirable to the bank) and that we would like to include in the effect of land title.23 Addressing the endogeneity concerns by using the standard instrumental variables approach is not satisfac

-22. A small number of households had more than one loan in the sample because they had

loans from multiple formal banks. In all loansize regressions, we include a dummy vari

-able that indicates these households.

23. Reverse causality is another possible explanation; borrowing households may use the loan to fund obtaining a land title. Since most loans are recent loans (those in the past four years) and the titling process is lengthy, having obtained a loan is not likely to mean that the household has obtained a land title. Unfortunately, we do not have information on when the land title was obtained.

tory, because the estimates asymptotically eliminate the ‘bias’ resulting from the correlation between land title and any unobservable variable correlated with credit access, consequently removing any signalling effect. Thus, if the signal -ling hypothesis is correct, the instrumental variables estimation will result in no effect. In contrast, pure collateral does not depend on personal characteristics, so the estimation should yield a positive and signiicant effect. Since not inding an effect in the former case could equally result from removing spurious correlation, we take a threepronged approach. We irst employ subdistrictlevel ixed effects, which correct for any confounding factors that do not vary within a subdistrict, such as lending practices that depend on the average characteristics in the lend -ing area.24 If we still observe an effect of possessing a land title, it could be due to idiosyncratic unobserved variation correlated with possessing a title. There are two obvious candidates. The irst is the availability of informal sources of credit as substitutes for access to formal credit. While we do not have a particularly good measure of informal credit availability, the MASS data contain information on credit from informal sources. Since the village or urban neighbourhood should cover the lending area for informal sources, we aggregate at the localitylevel the total amount of informal credit and then normalise by the total amount of formal credit in the locality. We include this measure as a control variable in order to account for the competition that informal sources of credit provide to formal lend -ers. The second candidate is idiosyncratic demand, which we discuss in ‘Assess -ing the Role of Credit Demand’, below.

Having Title versus Offering It?

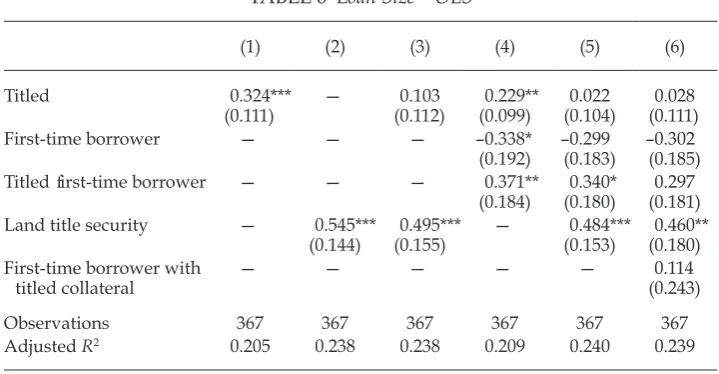

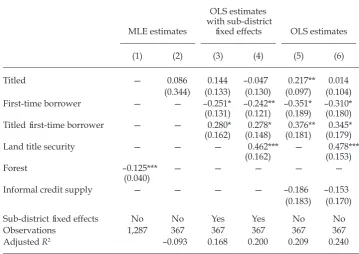

The results in table 6 give least squares estimates for all borrowers, using a full set of controls. Since we have taken the log of the dependent variable in the regres -sions with loan size, the coeficients must be converted to obtain the desired mar -ginal effects. In the irst column, the coeficient on possessing a title is positive and statistically signiicant at the 1% level. Having a land title is associated with a 38.3% increase in loan size. In the second column, we replace the dummy variable for having a land title with a dummy variable for offering a land title as collateral, which is associated with a 72.5% increase in loan size and is signiicant at the 1% level. In the third column, we include both dummy variables, having a land title and offering it as collateral. Offering a land title as collateral has a similar magnitude to the unconditional estimate, 81.8%, and is statistically signiicantly different from zero (jointly signiicant at the 1% level). Conditional on being titled, the effect of offering a land title as collateral is an increase in loan size of 64.0% (signiicant at the 1% level) and possession alone is not statistically different from zero. This evidence is consistent with the hypothesis that only the collateral value of land title matters in the credit market in Indonesia. Thus, for all borrowers, this test is inconclusive as evidence for the signalling value of a land title.

The fourth and ifth columns of table 6 represent the preferred empirical test, repeating the irst and second columns and introducing a dummy variable for

24. Using localitylevel ixed effects is problematic from a statistical point of view, both be -cause of the loss in degrees of freedom and be-cause there is little withinlocality variation in the main explanatory variable, the titled irsttime borrower dummy—44 of 72 villages had no titled irsttime borrowers, compared with 14 of 36 subdistricts.

Signalling Creditworthiness: Land Titles, Banking Practices, and Formal Credit 451

TABLE 6 Loan Size—OLS

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

Titled 0.324***

(0.111) — (0.112)0.103 (0.099)0.229** (0.104)0.022 (0.111)0.028

Firsttime borrower — — — –0.338*

(0.192) –0.299(0.183) –0.302(0.185)

Titled irsttime borrower — — — 0.371**

(0.184) (0.180)0.340* (0.181)0.297

Land title security — 0.545***

(0.144) (0.155)0.495*** — (0.153)0.484*** (0.180)0.460** Firsttime borrower with

titled collateral

— — — — — 0.114

(0.243)

Observations 367 367 367 367 367 367

Adjusted R2 0.205 0.238 0.238 0.209 0.240 0.239

Note: This table presents the coeficients obtained from an OLS model with the log of formal bank loan amounts (in 2002 CPIadjusted rupiah) as the outcome variable. The un reported controls used in these regressions are years of schooling (group dummies), household head’s age, asset value (in logs), income per capita relative to the poverty line, has ixed salary, household size, years in current loca-tion, locality average income per capita relative to the the poverty line, population density in locality, whether locality has a bank, and a rural subdistrict dummy. We also include an indicator for house-holds with recent loans from multiple institutions. Missing observations are due to incomplete loan information and missing data on some control variables. Standard errors are reported in parentheses and are robust, clustered at the subdistrict level.

* p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

being a irsttime borrower and an interaction term between possessing a land title and being a irsttime borrower. As discussed earlier, if a formal land title functions as a signal it should be more important for irsttime borrowers. The fourth column shows that the effect of possessing a formal land title for irsttime borrowers is statistically signiicantly different from the effect for more experi -enced borrowers. Since the information problem is most apparent for irsttime borrowers, our interpretation is that banks use formal land titles as signals of important unobservables.25 The size of the effect is large, yielding an 82.2% (joint signiicance at 1%) increase in loan size for irsttime borrowers with land titles when we do not control for offering the land title as collateral and a 43.6% (jointly signiicant at the 10% level) when we do control for it. However, the differential effect, γ3, remains stable, at 44.9% in the fourth column and 40.5% in the ifth, and signiicantly different from zero at the 10% level. This means that the differential

25. If banks use methods other than securing collateral, then the information effect observed

in comparing irsttime and experienced borrowers may relect expost or exante informa

-tional constraints. In giving an example of an exante informa-tional effect, Bester (1985) shows that banks can screen for borrower types with low repayment costs by offering loan contracts with higher collateral requirements at a lower interest rate. The expost informa -tion effect could work by using reputa-tionbased contractual enforcement in which formal titles improve the observability of default.

TABLE 7 Loan Size —Robustness

MLE estimates

OLS estimates with sub-district

ixed effects OLS estimates

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

Titled — 0.086 0.144 –0.047 0.217** 0.014

(0.344) (0.133) (0.130) (0.097) (0.104)

Firsttime borrower — — –0.251*

(0.131) –0.242**(0.121) –0.351*(0.189) –0.310*(0.180)

Titled irsttime borrower — — 0.280*

(0.162) (0.148)0.278* (0.181)0.376** (0.179)0.345*

Land title security — — — 0.462***

(0.162) — (0.153)0.478***

Forest –0.125***

(0.040) — — — — —

Informal credit supply — — — — –0.186 –0.153

(0.183) (0.170)

Subdistrict ixed effects No No Yes Yes No No

Observations 1,287 367 367 367 367 367

Adjusted R2 –0.093 0.168 0.200 0.209 0.240

Note: The dependent variable is the log of formal bank loan amounts (in 2002 CPIadjusted rupiah), with the exception of column 1, which presents the irststage results of using a dummy variable indicating whether a village is located in an oficially designated forest area as an instrumental vari-able. Columns 1–2 are results from multiequation MLE, where the irststage equation is run on the whole sample and the secondstage is restricted to formal bank borrowers. Columns 3–4 are coeficient estimates from an OLS model with subdistrictlevel ixed effects. Columns 5–6 add the measure of informal credit supply as a control variable. The unreported controls used in these regressions are years of schooling (group dummies), household head’s age, asset value (in logs), income per capita relative to the poverty line, has ixed salary, household size, years in current location, locality average income per capita relative to the poverty line, population density in locality, whether locality has a bank, and a rural subdistrict dummy. We also include an indicator for households with recent loans from multiple institutions. Missing observations are due to incomplete loan information and missing data on some control variables. Standard errors are reported in parentheses and are robust, clustered at the subdistrict level, except for columns 1–2.

* p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

effect is similar whether or not we control for offering the land title as collateral. We view this as strong evidence for the signalling value of a land title.

In the sixth column, we check an important assumption underlying the pre -ferred test: that the pure collateral effect is the same for repeat and irsttime bor -rowers if we hold ixed the information about the two types of bor-rowers. That is, in the sixth column we allow for the collateral effect to vary by borrower type. The coeficient on being a irsttime borrower and offering land title as collat -eral is not statistically different from zero, justifying the speciication in the ifth column. More important, the coeficient on being a titled, irsttime borrower remains positive and statistically signiicant at the 10% level, although the magni -tude decreases. Given the sample size and the relatively few irsttime borrowers,

Signalling Creditworthiness: Land Titles, Banking Practices, and Formal Credit 453

these two variables differ across a small number of observations, which may sug -gest that the drop in magnitude is a feature of the small sample.

To conirm the signalling hypothesis, we compare the instrumental variables and subdistrict ixed effects speciications. In table 7, the irst column presents the irst stage for our instrument, the ‘Forest’ dummy taken from Podes. In the irststage probit, the marginal effect of the ‘Forest’ dummy is negative and statis -tically signiicant at the 1% level. As would be expected if land title has a signal -ling value, the instrumental variables estimation, with the inal stage presented in the second column, removes the effect for land title. The third and fourth columns show that the results remain largely unaffected when we control for unobserv -able factors that are ixed within a subdistrict. In the third column, the effect of possessing a title for irsttime borrowers is statistically (jointly) signiicant at the 10% level, so we can reject the hypothesis that the effect for irsttime borrowers is the same as for experienced ones. However, controlling for land title as collateral makes the joint effect lose statistical signiicance at the 10% level. We are not too concerned about this loss of statistical signiicance, because the differential effect remains statistically signiicant and because this speciication is demanding on the data.26 More important, in the third and fourth columns the precision and magnitude of the differential effect remain stable and statistically signiicant.

The ifth and sixth columns account for localitylevel differences in informal sources of credit. The coeficient on informal credit supply has the expected sign if informal and formal sources of credit are substitutes but it is statistically insigniicant (pvalue = 0.317) and cannot be distinguished from zero. However,

its inclusion slightly improves the measurement of the effects of the titled vari -ables, suggesting that controlling for local variation in informal credit supply soaks up some noise in the regression of formal loan size. The effect of being titled for irsttime borrowers increases relative to the main speciication whether we control for offering a land title as security (in the sixth column) or not (in the ifth).

Assessing the Role of Credit Demand

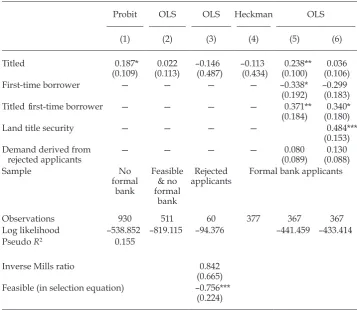

The effects described so far could be due at least partially to titled households demanding more inancing, rather than to shifts in credit supply. Formal land titles may increase investment incentives or simply correlate with the desire for larger loan amounts. We attempt to address this issue in this section by focus -ing on hypothetical supply (com-ing from the loan oficer’s assessments of survey respondents) and on information on demand from the rejected loan applications. We observe the following for all loan applicants:

yi=min (demand

i, supplyi) (2)

Focusing on hypothetical feasible loan amounts (judged by loan oficers) and on the demanded amounts of those who were rejected for a loan allows us to bypass the supplyconstrained assumption and the observational limitations expressed

26. Twothirds of subdistricts had zero titled irsttime borrowers who did not offer this land title as security for their loan (compared with onethird of subdistricts with zero titled irsttime borrowers).

TABLE 8 Hypothetical Supply and Derived Credit Demand

Probit OLS OLS Heckman OLS

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

Titled 0.187*

(0.109) (0.113)0.022 –0.146(0.487) –0.113(0.434) (0.100)0.238** (0.106)0.036

Firsttime borrower — — — — –0.338*

(0.192) –0.299(0.183)

Titled irsttime borrower — — — — 0.371**

(0.184) (0.180)0.340*

Note: Column 1 presents a probit model with an indicator of a feasibility judgment as the outcome vari-able. Marginal effects are reported at the median. Column 2 presents coeficient estimates from an OLS model using feasible loan amounts as a dependent variable. Both columns restrict the sample to exclude the formal bank borrowers. Column 3 presents an OLS model with log of formal bank loan application amounts as the outcome variable for only those applicants who were rejected. Column 4 presents a Heckman selection model using whether or not a household had a feasibility judgment as the selection variable. Columns 5–6 use predicted loan demand for all formal bank users as a control in the main speciication. The unreported controls used in these regressions are years of schooling (group dummies), household head’s age, asset value (in logs), income per capita relative to the poverty line, has ixed salary, household size, years in current location, locality average income per capita relative to the the poverty line, population density in locality, whether locality has a bank, and a rural subdistrict dummy. In columns 5–6, we also include an indicator for households with recent loans from multiple institu-tions. Missing observations are due to incomplete loan information and missing data on some control variables. Standard errors are reported in parentheses and are robust, clustered at the subdistrict level.

* p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

by equation (2). For households that applied for a loan but were rejected, instead of only observing yi we also know the amount demanded directly. Hence, for

those rejected, we know that the effect of title on the amount demanded is purely the demand effect, since there is no supply effect present. Given the difference in characteristics shown in table 5, we employ a selection equation to uncover the probability of rejection so that we can look at the demand effect for all borrowers. We use whether the survey enumerator judged that it was feasible to extend a

Signalling Creditworthiness: Land Titles, Banking Practices, and Formal Credit 455

loan to the household as an independent inluence on the probability of rejection. As discussed in the previous section, this feasibility judgment should be corre -lated with the probability of rejection, since those who are making the judgements are BRItrained loan oficers. We argue that a feasibility judgment should not be correlated with the recent loan amount demanded by the applicant, since only supply considerations are taken into account in this assessment—that is, whether BRI would lend to a certain household with certain characteristics and at what amount, completely independent of the potential demand for such a loan or loan amount. With the estimated probability of rejection, we can use the demanded amounts from the rejected applicants to predict the demanded amounts for all borrowers.27 Once we have reconstructed a measure of demanded loan amounts for all borrowers, we can then control for idiosyncratic demand in the preferred speciication and rerun the main results.

In the irst column of table 8, the dependent variable is whether a household received a feasibility judgment by the loan oficer (at the time of the survey). We restrict our attention to households without formal loans. Having a title is statistically signiicant at the 10% level and the coeficient is positive. The sec -ond column reports the effect of possessing a land title on feasible loan amounts (hypothetical supply). Here, the coeficient on having a land title is positive but not statistically signiicant, and the point estimate is small (pvalue = 0.846). The

fact that the loan oficers interview potential borrowers extensively in the bor -rowers’ homes suggests that the loan oficers may have better observability than other bank employees would if potential borrowers were to come to a branch. Therefore, this informational advantage may weaken the estimates of the effect of a land title.

The results that we present in the third to sixth columns of table 8 incorporate the information from rejected loan applications. Being titled has no relation to the requested loan amounts of those who have been rejected, as shown in the third column. In the fourth column, we present the results after having corrected them for the probability of being rejected. While a feasibility judgment negatively pre -dicts being rejected and is statistically signiicant, the probability of being rejected is not statistically related to demand. The fourth column shows that the effect of possessing a title is not statistically signiicant for credit demand. With this regression, we predict the demanded loan amounts for all applicants. (Note that we do not use all the information available here, since we do not use informa -tion about demand that is contained in the observed loan amounts.) Adding the predicted credit demand as an explanatory variable, we can then reestimate the effect of a land title for irsttime borrowers. Predicted demand is positive but not signiicant at the 10% level and the effect of a land title for irsttime borrowers is virtually unchanged.28 These results suggest that demand is not driving the observed relation between land titles and loan amounts.

27. We employ a Heckman selection model for this procedure.

28. The demand variable is a generated regressor and the standard errors are not correct, so the signiicance level should be interpreted with caution. We do not make the correction

here, because we wanted to check only whether the inclusion of the demand variable affect

-ed the coeficients on having a land title and the interaction term with irsttime borrowers.

TABLE 9 Formal Banking Participation: Probit Model

Probit Biprobit Heckman

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5)

Titled 0.091**

(0.040) (0.036)0.073** (0.488)0.009 (0.137)0.170 (0.144)0.101

Firsttime borrower — — — — –0.302*

(0.171)

Titled irsttime borrower — — — — 0.333

(0.205)

Land title security — — — 0.475***

(0.121) (0.120)0.464***

Log distance to bank — –0.099*

(0.053) –0.110(0.110) — —

Observations 1,287 1,287 1,287 1,282 1,282

Log likelihood –661.330 –632.670 –1,284.666

Pseudo R2 0.144 0.182

Inverse Mills ratio 0.265 0.332

(0.401) (0.403)

Log distance to bank (in selection equation) –0.402***

(0.126) –0.402***(0.126)

Note: In columns 1–2, this table presents a probit model with an indicator of having had a formal bank loan as the outcome variable. Column 1 uses only income, asset, and household variables as controls. Column 2 adds household and villagelevel characteristics as controls. Column 3 uses a bivariate pro-bit model in which both loan participation and having a land title are treated as dependent variables. The forestedarea dummy variable is used as an independent variable. For columns 1–3, marginal effects are reported at the median. Columns 4–5 present coeficient estimates from a Heckman selec-tion model with the log of distance to the nearest formal bank included in the formal loan participaselec-tion equation. Standard errors are reported in parentheses and are robust, clustered at the subdistrict level. The unreported controls used in these regressions are years of schooling (group dummies), household head’s age, asset value (in logs), income per capita relative to the poverty line, has ixed salary, house-hold size, years in current location, locality average income per capita relative to the the poverty line, population density in locality, whether locality has a bank, and a rural subdistrict dummy. In columns 4–5, we also include an indicator for households with recent loans from multiple institutions. Miss-ing observations are due to incomplete loan information and missMiss-ing data on some control variables. Standard errors are reported in parentheses and are robust, clustered at the subdistrict level.

* p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

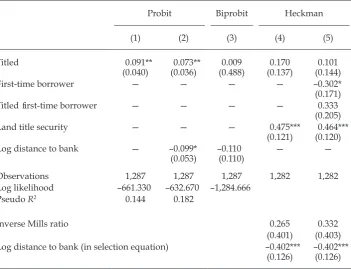

Incorporating Formal Banking Participation

We prefer to analyse participation separately from loan amounts. To get an idea of how land titles affect formal banking participation, and because the outcome of interest is binary, we make a further assumption on the error structure. We use a probit model, letting y * be the latent variable that tracks the unobserved value of

obtaining a loan to household i:

y*i=Χiβ+γTi+Ei (3)

where E∼N(0,1),y=I[y*>0] and P