Esteban R. Brenes

INCAEJon Martı´nez

UNIVERSIDAD ADOLFOIBA´ N˜EZ

Esteban S. Skoknic

ENDESAThis is the success story of an electric company that was founded in the

Buenos Aires, May 15, 1992

1940s as a public enterprise but that has been run since its founding asIn the SEGBA Hall of the Board of Directors, Jose´ Yuraszeck,

though it were a private company. Throughout the years, it has operated

President of the Board, and Jaime Bauza´, General Manager,

efficiently and with a high level of technology. The company was privatized

were euphoric as the consortium headed by ENDESA was

in 1987, and its performance improves still further, making it a success

awarded the contract for 60% of Central Costanera S.A.

Lo-model for Latin America. As frequently happens with successful,

high-cated in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Costanera was the largest

growth companies in the region, ENDESA began to face some limits to

thermoelectric plant in South America, with almost 1,260 Mw

expansion in its domestic market and began generating a surplus beyond

of installed capacity. With assets worth more than US $3

its investment requirements. In fact, the company projected that its cash

billion and annual sales of US$400 million, ENDESA was

flow would exceed projected investments by 500 million dollars. Most

Chile’s largest private company and the country’s leader in

Latin American companies, when confronted with this kind of situation,

generation and transport of electrical energy. This was the

would invest within its home country, in nonrelated businesses, creating

first time ENDESA would be investing in a foreign country

a diversified business group. In contrast, ENDESA decided explicitly not

(See Table 1).

to diversify in nonrelated businesses but rather to pursue its core business in other countries, beginning with neighboring Argentina. This first project

outside Chile required a large financial investment, an enormous organiza-

Buenos Aires, August 3, 1992

tional effort, and the need to forge strategic alliances with multinationalHeadlines on the front page of an Argentine newspaper:

“Chil-enterprises. The case describes this initial experience in detail, emphasizing

eans head electric business in Buenos Aires,” in reference to

the importance of human resources in any internationalization effort. It

the contract awarded to the Distrelec consortium in which

is clear from the case that ENDESA’s most valuable assets for success in this

ENDESA was participating, with 51% participation by Edesur,

effort were managerial. The dilemma now facing ENDESA management is

the business responsible for distributing over 50% of Buenos

whether to continue investing in Argentina. A new opportunity for the

Aires’ electrical energy.

expansion of electric power has arisen, but an investment of $100 million is required. ENDESA must make this investment decision in an

environ-ment of economic decline in Argentina. Other options include seeking

Santiago, November 18, 1992

investments in other South American countries, or perhaps investing inother sectors in Chile. J BUSN RES2000. 50.57–70. Elsevier Science The ENDESA board meets to make a decision on whether to

participate in the next bid opening in the Argentine electrical

Inc. All rights reserved.

sector, and in particular the Hidronor hydroelectric installa-tions, to be awarded in February 1993. Just one year after deciding to go international, ENDESA had already invested something over US $96 million in Argentina. A new

invest-Address correspondence to E.R. Brenes, INCAE, P.O. Box 960-4050, Alajuela,

Costa Rica. ment in Hidronor could easily double that amount. Board

This version of the case was written by Esteban R. Brenes, Profesor of members asked themselves if it was a good idea to continue Business Administration, INCAE, based on the case study, “The

International-ization of ENDESA” and “Note on the Electrical Industry in Chile and Latin investing in Argentina or whether it would be better to wait

American”, prepared by Esteban S. Skoknic, ENDESA executive and graduate for opportunities in other Latin American countries. of the Executive MBA Program at Valparaiso Business School, Adolfo Iba´n˜ez

University, and Professor Jon Martı´nez E., from the same university. While privatization of the Argentine electric sector, begun

Journal of Business Research 50, 57–70 (2000)

2000 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN 0148-2963/00/$–see front matter

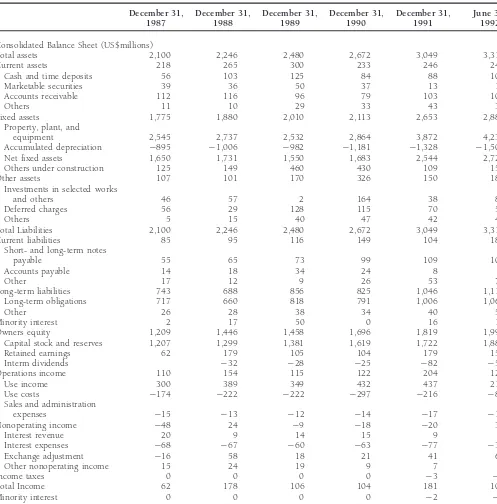

Table 1. ENDESA Financial Statements

December 31, December 31, December 31, December 31, December 31, June 30,

1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992

Consolidated Balance Sheet (US$millions)

Total assets 2,100 2,246 2,480 2,672 3,049 3,317

Current assets 218 265 300 233 246 248

Cash and time deposits 56 103 125 84 88 103

Marketable securities 39 36 50 37 13 12

Accounts receivable 112 116 96 79 103 101

Others 11 10 29 33 43 32

Fixed assets 1,775 1,880 2,010 2,113 2,653 2,884

Property, plant, and

equipment 2,545 2,737 2,532 2,864 3,872 4,231

Accumulated depreciation 2895 21,006 2982 21,181 21,328 21,502

Net fixed assets 1,650 1,731 1,550 1,683 2,544 2,729

Others under construction 125 149 460 430 109 155

Other assets 107 101 170 326 150 185

Investments in selected works

and others 46 57 2 164 38 84

Deferred charges 56 29 128 115 70 52

Others 5 15 40 47 42 49

Total Liabilities 2,100 2,246 2,480 2,672 3,049 3,317

Current liabilities 85 95 116 149 104 185

Short- and long-term notes

payable 55 65 73 99 109 101

Accounts payable 14 18 34 24 8 7

Other 17 12 9 26 53 76

Long-term liabilities 743 688 856 825 1,046 1,118

Long-term obligations 717 660 818 791 1,006 1,063

Other 26 28 38 34 40 54

Minority interest 2 17 50 0 16 18

Owners equity 1,209 1,446 1,458 1,696 1,819 1,996

Capital stock and reserves 1,207 1,299 1,381 1,619 1,722 1,888

Retained earnings 62 179 105 104 179 158

Interm dividends 232 228 225 282 250

Operations income 110 154 115 122 204 124

Use income 300 389 349 432 437 217

Use costs 2174 2222 2222 2297 2216 282

Sales and administration

expenses 215 213 212 214 217 211

Nonoperating income 248 24 29 218 220 38

Interest revenue 20 9 14 15 9 3

Interest expenses 268 267 260 263 277 239

Exchange adjustment 216 58 18 21 41 69

Other nonoperating income 15 24 19 9 7 4

Income taxes 0 0 0 0 23 22

Total Income 62 178 106 104 181 100

Minority interest 0 0 0 0 22 22

Net income 62 179 106 104 179 158

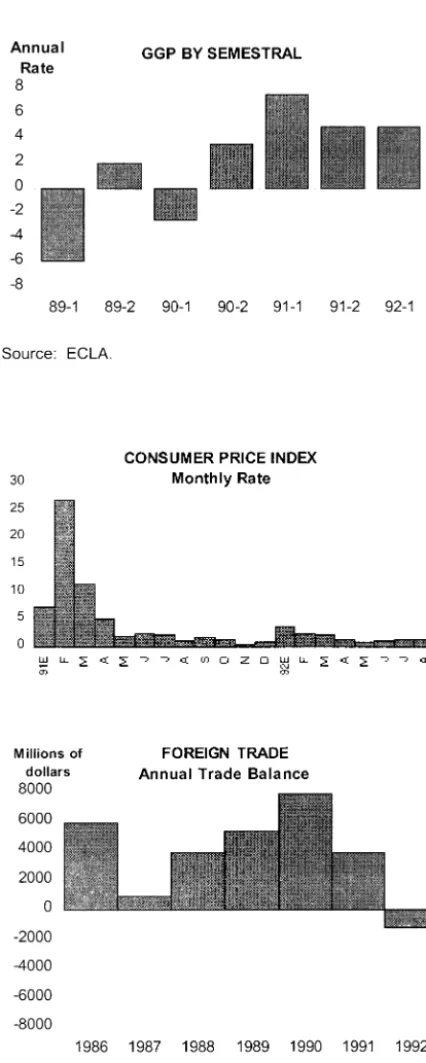

one year ago, was unfolding as planned, the country’s economy beginning of the 1940s, Chile’s electricity had been supplied exclusively by private companies. A shortage of supply during was behaving erratically. This led to a discussion of the major

concern that ENDESA management had voiced when invest- the 1930s, due to financial difficulties caused by the world depression, and the artificially low prices resulting from grow-ments were initiated in Argentina: the macroeconomic

situa-tion in this neighboring country and the political conse- ing governmental regulation led to active state participation in the development of the electric sector through the creation quences should the situation deteriorate.

of ENDESA, an affiliate of the Production Promotion Corpora-tion (Corporacio´n de Fomento de la Produccio´n.), or CORFU.

Company Background

The National Electric Company (Empresa Nacional Ele´c-trica, ENDESA) began operations in 1943 with the mission Ever since the first installations were established for public

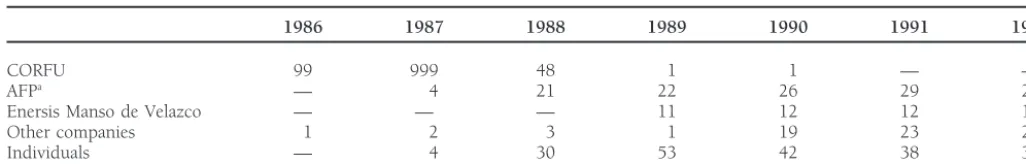

Table 2. ENDESA Shares on December 31

1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992

CORFU 99 999 48 1 1 — —

by CORFU. In order to give the company broad managerial Along with these events, decentralization policies were be-autonomy, it was decided from the outset to establish ENDESA ing applied in the energy sector. This included deconcentra-as a corporation, controlled by CORFU. Its initial activity tion of activities though the creation of several different enter-involved the design and construction of facilities, principally prises working in the generation, transmission and hydroelectric plants, as well as the development of transmis- distribution of energy. In 1980, ENDESA began a process of sion systems for these plants. gradual organizational transformation in order to adjust to In compliance with its mission, ENDESA had built and the new policies. Its most important actions had been the put into operation 70% of Chile’s electrical generation capacity formation of regional distribution companies, organization during the last 50 years (85% if only public utilities are consid- of the Pullinque and Pilmaique´n hydroelectric projects as ered). ENDESA also had developed the transmission networks affiliates, the creation of the large Colbu´n-Mchicura and Pe-that ultimately became the “Central Interconnected System” huenche generation projects as independent subsidiaries of and the “Great Northern Interconnected System.” This, along CORFU, and transfer to CORFU of electric companies outside with the development of distribution in various areas of the the Central Interconnected System.

country, had made it possible to broaden coverage of electrical Transfer of distribution affiliates and the Pullique and Pil-supply; in 1945, only 25% of the population had electricity, maique´n power plants to the private sector took place between but this percentage had increased to 80% by 1992. During 1981 and 1986. During the second half of 1987, CORFU this period annual consumption per capita had risen from began to privatize ENDESA by selling public shares, with 125 to 1,060 Kw. preference given to company workers and public employees.

From its creation, ENDESA was distinctive for its

develop-Stock ultimately was placed among more than 60,000 share-ment of national engineering capacity and technical

excel-holders. Table 2 illustrates the evolution of ENDESA shares lence. The first aspect was demonstrated by the company’s

on December 31stof each year.

emphasis on providing technical training for its professionals

In April 1990, ENDESA’s first Board of Directors without in order to solve problems in which Chile had no experience.

government representation was selected. The new Board then As a consequence, ENDESA could use its own engineering to

proceeded to name Jaime Bauza´, a 47-year-old civil engineer conduct the construction of large works and to make efficient

with extensive experience in the Chilean electric sector as use of installations. As a result, the company earned high

General Manager of the company. Mr. Bauza´ had been a prestige throughout Latin American and received numerous

director of Chilectra, general manager and board member of requests for consulting services in other countries. The

philos-Chilgener, and, at the time he was hired, general manager of ophy of technical excellence had led to the delivery of top

Pehuenche. quality service in comparison with international standards.

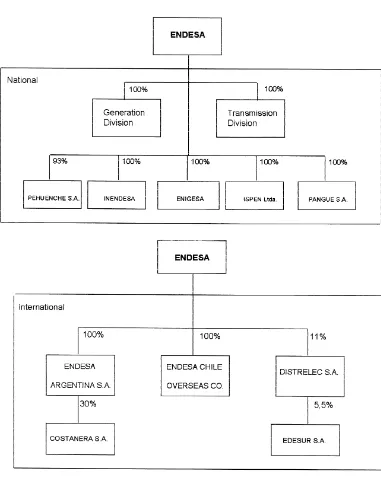

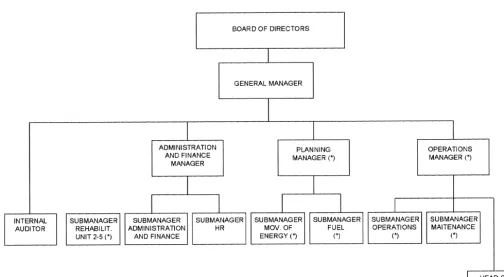

The new management’s first concern was to further im-The emphasis on efficient management was reflected in the

prove efficiency and create a decentralized organization. To stability of its administrative personnel. There had been only

achieve this, activities were structured into separate companies eight general managers during 45 years under government

(Figure 1), each reporting separately to the Board and related control.

to one another only by the market. ENDESA continued to be responsible for executing the

For tax purposes, ENDESA’s principal activities, the genera-Electrification Plan until 1978, when the National Energy

tion and transmission of electric energy, remained as company Commission (Comision Nacional de Energı´a or CNE) was

divisions. Engineering and project administration were orga-created. This new agency took charge of determining sectoral

nized in an affiliate company called Ingendesa, which provided policy and planning, thus limiting ENDESA’s role to that of

engineering services for the companies in the group and also producer. One of CNE’s major activities was to define

strate-sought to apply its abilities in penetrating other national and gies for sectoral development consistent with the government’s

international markets. It was expected that by 1992, 35% of overall economic policy, which emphasized the establishment

Ingendesa’s income would be generated by work performed of conditions for economic efficiency in the energy sector

Figure 1. Company configuration and equity structure. Note: Direct and indirect participation as of October 1992.

carry out construction and later exploitation of hydroelectric hired for the financial area, and greater emphasis was placed on the company’s participation in capital markets. In the facilities of the same name, located on the Bio-Bio River.

Employee health services were awarded to Ispe´n, and En- personnel area, changes were made in criteria for promotion, and the salary structure was reviewed in order to gear it to igesa was in charge of administering ENDESA’s nonproductive

properties. Financial management, personnel policy, and se- productivity rather than to seniority. After an analysis of the organization revealed an excess of personnel in all areas of lection of new investment projects were centralized in the

corresponding management areas of finance, industrial rela- the company, there was a reduction of almost 20% of the workforce. By June 30, 1992, ENDESA and its affiliates had tions, and development.

Accompanying these changes in organization structure a total of 2,369 employees.

Since the company’s privatization, it had attained signifi-were modifications in administrative policy. New executives

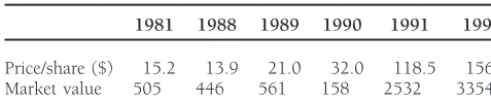

Table 3. Closing Stock Prices and Market Value in December of Ayse´n, and Magallanes. The few centers of population in this

Each Year zone were separated by large distances. Production of electrical

energy represented barely 1% of national production and

1981 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992

consists primarily of hydroelectric generation in Ayse´n and

Price/share ($) 15.2 13.9 21.0 32.0 118.5 156.5 gas generation in Magallanes. Total generation in the zone Market value 505 446 561 158 2532 3354 during 1991 was 253 GWh, of which 115 GWh came from

auto-producers and the rest from public utilities. Generation and distribution were carried out by DELAYSEN, in Ayse´n, and EDELMAG, in Magallanes.

most heavily traded in the stock market, representing 15 to

Overall energy consumption in Chile had increased by 5.1, 20% of daily market activity. Table 3 shows closing stock prices

4.5, and 4.5%, respectively, during the 1960s, 1970s, and and market value at nominal par in December of each year.

1980s; during the same periods, these rates were 6.8, 5.7, and 4.8% in the Central Interconnected System. Expected growth rates in the Central Zone for energy consumption

The Electric Energy Sector in Chile

derived from public utilities during the 1990s were estimated Activities in Chile’s electric energy sector were fragmented

at an accumulated average of between 5 and 6%. among a number of mostly by public utility companies. In

addition, industrial and mining companies auto-produced

electrical energy to supply their own needs. Total installed

The Provision and Regulation

capacity in Chile amounted to 5,100 Mw in 1992, and grossof Electric Energy

production in Chile during 1991 had equaled 19,808 GWh,

of which approximately 20% came from auto-production. The Provision of electric energy service involved three processes: generation, transmission, and distribution. Each of these pro-1992 estimate for this figure was 21,500 GWh.

In terms of electrical supply, there were three autonomous cesses had different characteristics at both micro and macro levels and in terms of government regulations.

zones with interconnected systems: Great Northern, Central,

and Southern. The Great Northern Zone included the Tara- It was accepted that no significant economies of scale ex-isted in electric energy generation, and the focus was on paca´ and Antofagasta area and joined all the cities between

Anca and Antofagasta and the mining centers between Chu- creating conditions for “regulated competition” through the elimination of plant construction permits (except for water quicamata and Escondida. This was a desert region with very

few hydroelectric resources, so for the most part generation use and safety standards), freedom in the prices applied to large customers (over 2 MW), determination of regulated was based on coal-based steam plants, representing 18% of

national production. The major generator in this zone was prices for marginal short-term costs of production, and the promotion of coordinated operations between generators and CODELCO’s 563 Mw Tocopilla Thermoelectric Plant. In

addi-tion to supplying Chiquicamata, the company also sold energy the spot markets. Finally, free and equal access by transmission systems was guaranteed.

to Edelnor (96 Mw), the only public utility generator in the

Great Northern Interconnected System. In 1991, total genera- Important economies of scale were recognized in the trans-mission of electricity. Required payments by generators for tion in the zone amounted to 3,498 GWh, of which 2,674

came from auto-production and the rest from public utility use of third-party transmission were calculated in relation to mean annual costs of investment and operation. Nevertheless, generators.

The Central Interconnected Zone supplied a 2,000-km– these costs were not established by the authorities but by common agreement among the parties or through arbitrage. long area from Taltal, to the north, and Isla de Chiloe´, to the

south. The zone consumed 81% of the country’s electrical In the distribution sector, the existence of natural monopo-lies by geographic area was recognized. Concessions were energy, and production was 60 to 90% hydroelectric,

comple-mented by coal-based thermoelectric generation. Total in- granted for certain zones, and companies were obliged to provide services in those particular areas. Prices for small stalled capacity for public service was 3,830 Mw, 78% of

which was hydroelectric. Principal producers included EN- consumers (under 2 MW) were set by authorities on the basis of the cost of purchasing energy and power from generators, DESA (1,928 MW), Chilgener (756 MW), Pehuenche (500

Mw), and Colbu´n-Machicura S.A. (490 Mw). Auto-producers plus a mean distribution cost. Calculation of this distribution cost was made on the basis of a typical company making had their own installed capacity of 6,056 GWh, including

1,323 GWh generated by auto-producers and the rest by investment decisions and operating efficiently. This cost was reviewed every four years by independent consultants con-public utilities. Principal distributor companies were Chilectra

Metropolitana, Chilectra Quinta Regio´n, Compan˜ı´a General tracted by the authorities and companies.

Contribution to the total cost of electric energy at each de Electricidad Industrial, Saesa, Frontel, EMEL, EMELAT,

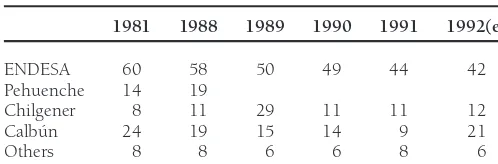

Table 4. Share of Generation (%) could be carried out without any problem.” exclaimed the

general manager. “And without affecting our classifications

1981 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992(e)

and commitments with the banks, we could even make

an-ENDESA 60 58 50 49 44 42 other $500 million worth of investments.”

Pehuenche 14 19 ENDESA’s Board President, Mr. Yuraszeck, also expressed

Chilgener 8 11 29 11 11 12 his opinion, saying, “Given its capacity and abilities, though

Calbu´n 24 19 15 14 9 21

it wouldn’t be easy, the company could successfully diversify

Others 8 8 6 6 8 6

into other fields such as telecommunications, forestry, or min-ing. However, this would make it a ’monster’ that Chile would probably not be willing to accept. Overly diversified compa-nies don’t fit the new environment.”

nected System, estimated average costs in U.S. cents per KWh,

Other Board members agreed that, given its primary capaci-calculated by the National Energy Commission in 1989, were

ties and abilities, ENDESA should focus on exploring new 3.2¢3for generation (51%); 0.7¢ for transmission (11%); and

businesses within the energy sector, in segments involving 2.4¢ for distribution (38%).

intensive use of electric energy and hydroelectric resources, and/or related activities in foreign-based projects with a high

ENDESA’s Situation in 1992

content of civil or hydraulic engineering in response tooppor-tunities opening up in other countries of the region. In point ENDESA participated in generation and transmission of

elec-of fact, by this time the Board already had approved investing tric energy in the Central Interconnected System, which

ac-up to 10% of the company’s assets in the foreign electric counted for 95% of all energy provided by public utilities in

energy sector. Chile. For electricity generation, the company had 1,928 Mw

of installed capacity (83% hydroelectric) in 15 plants,

includ-ing its affiliate Pehuenche (a 500-Mw power plant). Also par-

The Electric Energy Sector in

ticipating in this market were the private company ChilgenerOther Latin American Countries

(756 Mw), the state-run Colbu´n (490 Mw), and several smaller

companies (156 Mw), all of which competed for customers In 1950, most electrical companies in Latin America were and for the execution of future projects. privately owned and served the most important centers of As shown in the Table 4, ENDESA’s participation in the population. During the 1950s and 1960s, nationalization took Central Interconnected System had fluctuated during recent place in all the countries, leading to the formation of large years, depending on hydrological conditions. national electric companies. Advances in geographic coverage Generating plants that would be entering service in 1997 and increases in generating capacity had been significant up had already begun or were about to start up construction. A until the mid-1980s. Nevertheless, the electric energy sector simulation of future operations indicated that participation had been accumulating a series of problems that, in most of the countries, resulted in a serious crisis that was interrelated by ENDESA and its affiliates would remain constant at around

with the overall economic crisis of that period. These problems 60% during the 1990s. ENDESA’s share of customer sales

included inadequate resource allocation, inefficient manage-had been approximately 65% in recent years, which was

ment of public sector electric companies, subsidized prices, greater than its own production because the company bought

and high levels of debt, all of which had led to serious financial energy from local generators. However, it was expected that

difficulties resulting in poor maintenance, delays in project in the next few years ENDESA would be adjusting its

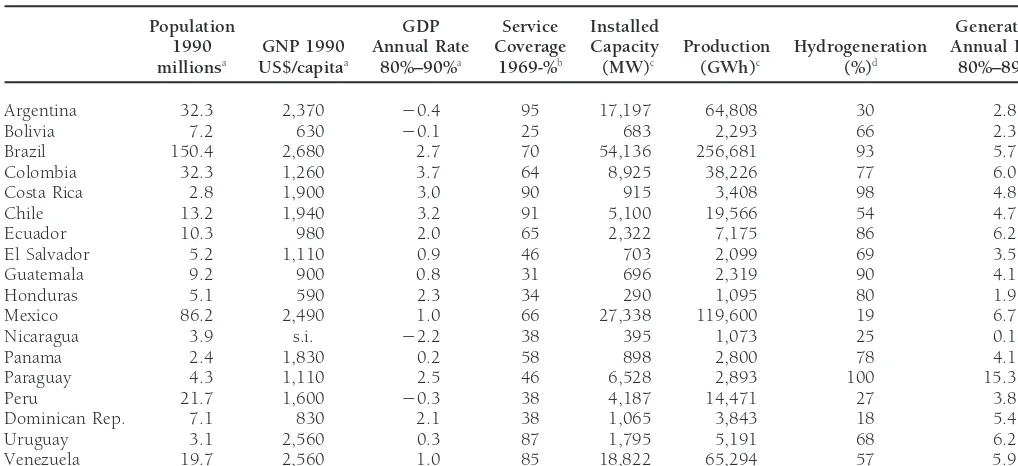

produc-start-ups, and ensuing shortages in supply (Table 5 summa-tion to meet projected sales.

rizes some of the most significant numbers for the sector). ENDESA had over 9,000 km of transmission lines, equal

to 75% of the high-tension network in the Central

Intercon-Argentina

nected System. Since no important expansion at the national

Table 5. Latin America Electric Sector

Population GDP Service Installed Generation

1990 GNP 1990 Annual Rate Coverage Capacity Production Hydrogeneration Annual Rate

millionsa US$/capitaa 80%–90%a 1969-%b (MW)c (GWh)c (%)d 80%–89%d

Argentina 32.3 2,370 20.4 95 17,197 64,808 30 2.8

Bolivia 7.2 630 20.1 25 683 2,293 66 2.3

Brazil 150.4 2,680 2.7 70 54,136 256,681 93 5.7

Colombia 32.3 1,260 3.7 64 8,925 38,226 77 6.0

Costa Rica 2.8 1,900 3.0 90 915 3,408 98 4.8

Chile 13.2 1,940 3.2 91 5,100 19,566 54 4.7

Ecuador 10.3 980 2.0 65 2,322 7,175 86 6.2

El Salvador 5.2 1,110 0.9 46 703 2,099 69 3.5

Guatemala 9.2 900 0.8 31 696 2,319 90 4.1

Honduras 5.1 590 2.3 34 290 1,095 80 1.9

Mexico 86.2 2,490 1.0 66 27,338 119,600 19 6.7

Nicaragua 3.9 s.i. 22.2 38 395 1,073 25 0.1

Panama 2.4 1,830 0.2 58 898 2,800 78 4.1

Paraguay 4.3 1,110 2.5 46 6,528 2,893 100 15.3

Peru 21.7 1,600 20.3 38 4,187 14,471 27 3.8

Dominican Rep. 7.1 830 2.1 38 1,065 3,843 18 5.4

Uruguay 3.1 2,560 0.3 87 1,795 5,191 68 6.2

Venezuela 19.7 2,560 1.0 85 18,822 65,294 57 5.9

aWorld Bank. bWorld Bank–OLADE.

cSouth America: CIER (generation1import2export, 1991), remander: ECLA (generation 1989). dECLA.

1980s. Forty percent of consumption was concentrated in

Peru

Buenos Aires. Growth rates in consumption for the next few Generation in Peru was essentially hydroelectric, although years were estimated at 5 to 6%. For the most part, this greater participation was anticipated for thermal generation increase would be covered by integrating the Piedra del Aguila, in the future. Electricity was provided by the state enterprise, Yacireta´ and Pichi Picu´n Leufu hydroelectric plants and the Electroperu´, and 10 companies. The most important of these, Arucha II nuclear plant, all under construction. There was a Electrolima, supplied 50% of the country’s consumers. In possibility of additional plants using natural gas. Until 1991, the 1980s, the Peruvian electric sector was characterized by almost all installed capacity was in the hands of federal or inefficient operations, artificially low prices, and significant ac-provincial companies, as was distribution, with the major cumulation of foreign debt. Combined with the country’s deteri-companies being Agua y Energı´a (3,940 Mw), SEGBA (2,680 orated economic conditions, this situation had seriously affected Mw), Hidronor (2,720 Mw), Salto Grande (1,260 Mw), and the sector’s capacity for expansion. Annual growth in consump-the National Energy Commission (1,020 Mw.) tion was estimated at 6.6% during the next few years.

As of 1991, the Argentine government decided to privatize

installations under federal control, except for the two bina-

Colombia

tional plants, Salto Grande and Yacireta´, and the nuclear In Colombia, generation was fundamentally hydroelectric, a plants. Methods for carrying out privatization were deter- situation that would remain constant in the near future. mined, and the legal foundation was established for develop- Growth in consumption was forecast at an annual 6.7% for ment of the sector. The principal concepts within the regula- the decade. Almost all electrical energy was generated, trans-tory framework were the ban on simultaneous participation mitted, and distributed by seven companies: three municipal in activities involving transmission and generation or distribu- companies (Bogota, Medallı´n. and Calı´), three regional state tion of energy; coordinated operation of generator plants enterprises (CCVC, CORELCA, and ICEL), and one-fourth within the national interconnected system; creation of a spot owned by other companies in the sector (ISA). The financial situation of the electric energy sector was seriously eroded due market for generators, distributors, and large customers for

to the insufficient self-generation of funds and devaluation. transactions at the marginal generation cost from instant to

instant; the possibility of establishing free price contracts

be-Venezuela

tween generators and distributors; competition in the area of

that was expected to persist into the future. Growth in con-

Ecuador

sumption for the coming years was estimated at 8.1% a year. Electric energy in Ecuador was hydroelectrically generated, The electric sector consisted of four state-run enterprises (CA- with thermal generation used for emergency situations. Con-DAFE, EDELCA, ENELVEN, and ENELBAR) and seven private sumption was expected to rise 6.7% a year. Generation and companies, with Electricidad de Caracas being the most im- transmission was the responsibility of INECEL, a government-portant of these. The sector had developed significantly during run company supplying electricity for 18 regional distribution recent years thanks to the use of an important part of the companies. Given the low prices and high foreign debt, the country’s petroleum resources. It was currently facing difficul- electric sector was facing difficulties in financing projects for ties due to an inadequate pricing policy and a weak financial expansion and satisfaction of future consumption demands. situation.

El Salvador

Uruguay

Generation in El Salvador was basically hydroelectric andUruguay’s electric energy supply was primarily hydroelectric geothermal, a situation that was expected to remain constant in origin and was generated by state-run enterprises and the during the 1990s, with annual growth in consumption pre-binational Salto Grande power plant. Use of thermal genera- dicted at 4.2%. Practically all generation was in the hands of tion was expected to rise slightly in the future. Generation, the Lemper River Executive Commission, a state-run enter-transmission and distribution were under the responsibility prise that sold energy to private regional distributor compa-of the National Administration compa-of Power Plants and Electrical nies. The electric sector had been seriously affected by the Transmission (UTE.) The sector had developed satisfactorily economic situation in El Salvador. Accumulation of debt and except for heavy debt resulting from the construction of hydro- the shortage of resources had made it difficult to maintain electric projects. This had created pressure to reduce invest- installations and carry out investment for expansion. ment in distribution, with the corresponding consequences.

Bolivia

Brazil

In Bolivia, electric energy supply was primarily hydroelectric,Brazil’s electric energy was almost exclusively hydroelectric. but thermal generation had been growing and would continue Although coal- and natural gas–based thermal generation also to grow in the future, given the ample availability of natural was being considered, the Brazilian system would continue gas in the country. Annual growth in consumption was esti-to be primarily hydroelectric. Growth in consumption was mated at 9.3%. The state-owned National Electric Company predicted at an annual 5.5% for the 1990s. Brazil’s electric (ENDE) was responsible for generation and transmission of energy sector was one of the largest in the world. The gov- electrical energy, while distribution was assigned to regional ernment-owned ELECTROBRAS served as both a holding companies. Bolivia had one of the lowest rates of coverage in company and development bank for the sector. Its four sub- the region despite its efforts during the last two decades. sidiaries, Furnas, Chef, Electrosul, and Electronorte, were re- During the 1980s, the electric energy sector had maintained sponsible for generation and high-tension transmission. It also satisfactory financial indices with little state funding required. administered 50% of the Itaipu´ tri-national power project. Solutions to the problems of the Latin American electric State governments owned the distribution companies serving energy sector included a range of possibilities, from the injec-their populations. A policy of low pricing for inflation-control tion of private capital—practically nonexistent before purposes had hindered financial stability and economic effi- 1992—to the integration of capacity for project management ciency in the sector, and the government had consequently and efficient exploitation. Structural reforms of the sector been obliged to provide significant contributions. The finan- were being studied in most countries, and in some cases the cial resources needed for investments were calculated at some privatization of existing installations was moving forward. It US$9 billion a year; this could not be financed by the sector was anticipated that these reforms would keep pace with the and external capital was needed. speed and intensity of structural changes within the economy

of each country.

Mexico

Generation in Mexico was primarily petroleum based and

The Argentine Opportunity

complemented by hydroelectric power. An increase ofproduc-tion using coal was expected. Annual growth in consumpproduc-tion In 1991, Argentina decided to privatize all government-owned activity in the generation, transmission, and distribution of was anticipated at 6.7%. The Federal Electric Commission

and its distribution branch, the Central Power and Lighting electric energy, until then carried out by three state-owned enterprises: SEGBA, Hidronor, and Agua y Energı´a. The pro-Company, supplied all electricity. Due to growing demand

era, with 1,260 Mw), and then continue with some of the and Costanera plants would be sold, along with a contract smaller thermal plants, the transmission network, and the for sale of energy to distributor companies for a period of hydroelectric plants. At the same time, distribution of electric eight years, with a price expressed in dollars and indexed in energy in Buenos Aires, to be divided between two companies, relation to the price of fuel. According to existing regulations, would be opened to bidding. Privatization would be carried the companies would be required to operate in coordination out within the framework of Argentina’s economic structural with the rest of the plants in the National Interconnected reform program, in which a regulatory framework was being System. These plants made up the market where surplus created for the sector. The goal of the reform was to provide would be sold and shortage would be purchased according a stable and consistent process to achieve the long-term objec- to the different supply contracts. This system had been selected tive of improving productivity in the sector. to promote efficient management, assure maximum availabil-The opening of bidding on electric generation companies ity of equipment, employ flexibility in satisfying changes in in Argentina occurred just as ENDESA was searching for new energy demand in Argentina, and regulate decisions by third business. The opportunity to acquire large plants that were parties in regard to expanding generation.

already operating within an electric system three times bigger With respect to the question of “how,” Yuraszeck said, than the one in Chile was not to be underestimated. In

addi-I think it’s crazy for Chilean companies to go into Argentina tion, there was the possibility of a future physical

interconnec-without local partners; while it may not be easy to find tion between the Chilean and Argentine electrical systems

them, Argentina is a much bigger country than Chile and by means of a 200-Mw–capacity line that would join the

to reach the top level of Argentine companies, we’ll have substations near Santiago and Mendoza. According to

to pound on a lot of doors. ENDESA officials, however, any decision to invest in Argentina

would have to be taken independently of this potential

inter-To participate in the first round of bidding on the thermal connection.

plants, ENDESA promoted the formation of a consortium in With respect to internationalization, Mr. Yuraszeck stated,

which it would have 50.1% participation through its affiliate These opportunities only come around once in life. In ENDESA Argentina, a company created for this purpose. An-a world An-as interrelAn-ated An-as it is todAn-ay, the most nAn-aturAn-al other 20% would be owned by the Chilean distributor compa-development for a company interested in growing is to go nies Chilectra Metropolitana and Enersis, 25% owned by the international. Argentine group Pe´rez Companc, and 5% by U.S. Public Ser-vices of Indiana. The consortium was awarded 60% of the Along with the decision whether to participate in the

priva-Costanera plant. It also bid on Puerto, but this was later tization of Argentina’s electric energy sector, ENDESA also

awarded to the Chilean companies Chilgener and Chilectras had to determine the best way of getting into the business.

Quinta Regio´n. Under the structure developed, ENDESA The company needed to decide if it should enter by acquiring

would assume total responsibility for operating the Costanera the large thermal plants that would justify the effort required,

plant. by acquiring small thermal plants to gain experience, or by

Elsewhere, ENDESA had 10% participation in the Inversora waiting for bidding to open on the large hydroelectric plants

Distralec consortium, which was granted 51% of the distribu-that were closer to the company’s previous experience and

tor company, Buenos Aires Edesur, for US$511 million. Be-that apparently had fewer technical problems.

sides ENDESA, this consortium consisted of Chilectra Metro-ENDESA executives felt that it was essential participate

politana and Enersis (39.5%), the Pe´rez Companc group in the first round of bidding in order to acquire sufficient

(40.5%), and Public Services of Indiana (10%). Chilectra Met-information about the Argentine electric energy sector, its

ropolitana would be the operator in this consortium. new regulatory framework, and the relevant labor and tax

legislation. Significantly, the Chilean companies were the only private businesses in Latin America that operated under rules

The Experience at Costanera

of the game that were similar to those being considered for

application by other countries in the region. As Mr. Yuraszeck Gunther Prett, a Chilean engineer with 40 years of experience mentioned, at ENDESA and Manager of the Transmission Division, as-sumed the position of General Manager at Costanera. Mr. Chilean companies in general and ENDESA in particular

Prett commented that during his first months of work he had had already gone through what Latin American electrical

never felt the days go by so quickly. The 12-hour workday companies were either experiencing or about to experience.

at the plant seemed too short a time to solve the problems that confronted him every day. The machines were in poor For the privatization of the large thermal plants, the Argentine

condition, and the plant had never functioned as an integrated Government had invited bidding on 60% of the company

business unit. Even so, progress was made: when ENDESA shares; 30% would be sold later on in the stock market, and

Figure 2. Costanera power plant organizational chart (asterisk signifies Chilean).

months later it was over 900 Mw. By September the company proximity and attractiveness of Buenos Aires, but the trans-fer of our people affected their family life. This is not a had earned US$2.2 million in profits.

The investment plan to rehabilitate machinery and start problem that is quickly solved, and it is one that is experi-enced by all Chilean companies that go international. The up the plant at Costanera was estimated to require US$200

million, including the manufacture of new equipment and most they imagined was one or two years abroad and back to Chile. We have not had enough time to prepare for the the necessary working capital. Initially these funds would be

obtained through loans from the Costanera partners them- decision to invest outside of Chile. This is a key issue, given that what ENDESA is doing is exporting management, mid-selves, but it was expected that in the near future the company

would have the debt capacity to obtain the additional outside level positions, and technology. resources needed.

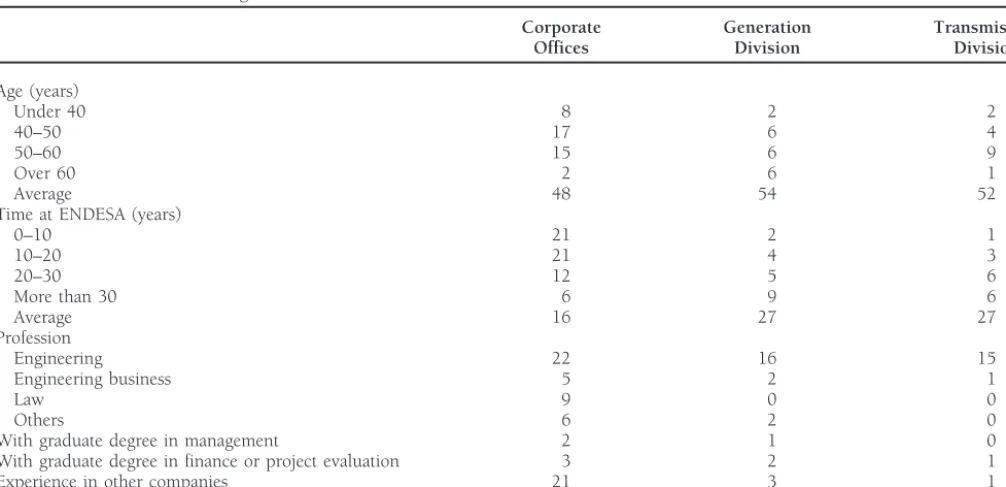

It was expected that labor issues would be among the most As the operator of Costanera, ENDESA was responsible for

conflictive. ENDESA had determined that considerably fewer its technical and administrative management, which meant

people were needed to run the plant than were working there getting the maximum utilization of its equipment and turning

at the time of the acquisition. Moreover, the prevailing work it into an efficient company. ENDESA’s commitment required

habits—some established by written agreement and others that it designate the principal executives. Of 14 managerial

accepted as normal—were incompatible with efficient admin-positions, 10 were named by ENDESA and 4 by its Argentine

istration. New management’s first measure was to offer a plan partners (see Figure 2). There were 14 permanent Chileans

for voluntary retirement, which required supplementing the and a support group that traveled from Chile for brief periods

government retirement funds available. Some of the eligible at Costanera’s request. Data on personnel occupying top-level

employees did in fact retire. By the end of the first year there positions at ENDESA’s corporate offices and at the Generation

were 730 people working at the Costanera plant, 320 less and Transmission Divisions are presented in Table 6.

than the original number, but new management felt this was According to Rodrigo Manubens, Vice-President of

EN-still too high. DESA, it had not been easy to fill positions at Costanera. Said

Another key labor issue was a new collective agreement Manubens,

Table 6. Personnel Statistics High-Level Positions at ENDESA

With graduate degree in management 2 1 0

With graduate degree in finance or project evaluation 3 2 1

Experience in other companies 21 3 1

and restrictions on overtime. Though no problems had yet us losing control. As a result there is an urgent need for structuring the organization in order to manage this new arisen in Costanera, other companies attempting to impose

similar clauses had experienced acts of sabotage in their pro- stage successfully. One option would be to decentralize management as much as possible, but establishing a pro-duction facilities. Mr. Prett observed that while morale among

the engineers was high, because “they now had the resources gram of control that would let us know exactly what’s going on and enable us to make corporate decisions quickly. The to do things that had not previously been possible,” there was

uncertainty as management awaited the results of collective second point that concerns me is what I call the $500 million plan. We need to continue having sufficient infor-bargaining.

The business style of Costanera executives was different mation for analyzing the investment options to make this plan a reality. My third concern is that all this will essen-than that to which people from ENDESA were accustomed.

For example, calls for bidding on services or acquisitions tially be financed through additional debt, so we need to have suitable financing sources. . . .

did not seem to promote genuine competition among the participants, nor was there any concern that the rules of the

Privatization in Argentina was now being continued with game in selecting bids be objective. In some cases there was

the Hidronor hydroelectric plants and transmission networks, doubt as to whether the company was really the primary

and this required that ENDESA review its internationalization interest. Consequently, though oversight responsibility for

strategy. In contrast to earlier positive expectations regarding ENDESA’s affiliates was generally delegated to their boards,

Argentina’s currency convertibility plan put forward by Minis-it was felt that the sMinis-ituation at Costanera required special

ter of Economy Domingo Cavallo, there were now signs of attention, and it in fact occupied most of the time of its Board

economic deterioration with the accompanying political risk. President, Jaime Bauza´.

It was expected that the balance of trade would show a deficit of over US$1 billion in 1992, the first negative balance in 10 years. Accumulated inflation was at 41% since the value of

Future Action

the dollar had been established, and the recently announced Despite these problems, Mr. Bauza´ felt that the results of these

measures to tax exporters and increase customs duties were first efforts toward internationalization had been

extraordi-seen as forms of covert sectoral devaluation. Elsewhere, indus-narily successful. He did have some concerns for the future,

trial production had been stagnant since March, and a drop which he expressed as follows:

in activity was predicted for 1993, in addition to the expecta-tion of a decrease in capital flows. In general, the economic The first point that concerns me is the organization of

ENDESA, which I would say is in a crisis of growth. All panorama was bleak, inspired distrust, and was reflected in a fall of over 50% in the stock market since the end of May. of us who work in the different areas are now involved in

restructured. The country that had made the greatest advances in privatizing the electric energy sector was Peru. It was ex-pected that a bill to regulate the sector, very similar to Chilean legislation, would be passed soon and that by early 1993 the process of privatizing existing installations would begin. ENDESA was assessing the possibility of forming joint negotia-tion units with the major generators dependent on Electroperu´ and Electrolima. It was felt that since risk in Peru was high at that time, the sales price of electric companies could be very attractive.

The current situation in other Latin American countries was as follows: In Colombia, electrical shortages resulting in cuts of up to 25% in consumption had precipitated a crisis. A law to restructure the sector and permit participation by private investors had been presented to Congress. Neverthe-less, the sale of assets was not expected to take place in the near future.

In Venezuela, privatization of electric companies had been on the table for some time. However, an attempted military coup had placed the stability of the elected government of Carlos Andre´s Perez in doubt and had delayed the timetable for the sale of electric companies. It was anticipated that the new regulatory framework for the electric sector would be passed in early 1993, accelerating the process of privatization. In Uruguay, the government was planning to call a plebi-scite in December 1992 to present to the public a Law on Public Companies that would permit privatization in areas under state control, including the electric energy sector.

The new government of Brazil had announced that it would keep its privatization program moving, but delays were ex-pected following a declaration that strategic areas would re-quire congressional approval. In any case, the size of Brazilian electric companies made them difficult to acquire, even for ENDESA.

New legislation passed in Costa Rica in 1991 permitted private participation in the generation of electric energy but in very limited form.

In Mexico, where the government had begun implementing a broad-based program to sell public companies, activities in the electric energy sector had not been included. These were reserved for the state by constitutional mandate and no changes in this situation were foreseen in the near future.

The new government in Ecuador would be initiating a process to reorganize the sector and to study a new regulatory

Figure 3. Argentine indicators: Industrial consumption of

electric-framework.

ity (top panel); salarial wages, March 915100 (middle panel), and

In El Salvador, the government had begun a study of

legisla-market index (bottom panel).

tion in the electric energy sector, and the privatization of hydroelectric plants was expected for 1993.

Thus, it appeared to ENDESA management that Argentina was the only country where a specific date had been set for President Menem had begun on November 9th. Figure 3

the privatization process and where rules of the game had presents current indicators of the Argentine economy.

been defined. The other countries would all be conducting Considering this situation, one option that ENDESA had

similar processes but still could not guarantee either the dates to explore was to consolidate in Argentina and make further

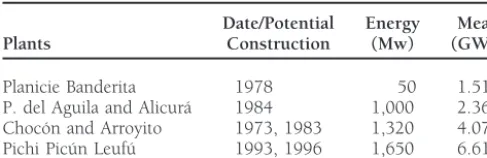

Table 7. Hidronor Power Plants would affect the reliability and cost of the electric energy

system.

Date/Potential Energy Mean

The Costanera plant had a long-term contract that covered

Plants Construction (Mw) (GWh)

the risk of changing prices on the spot market. Unlike thermal

Planicie Banderita 1978 50 1.510 plants, hydroelectric generation such as Hidronor’s was totally P. del Aguila and Alicura´ 1984 1,000 2.360 dependent on climatic conditions. With or without a contract Choco´n and Arroyito 1973, 1983 1,320 4.070

for energy sales, these conditions would interact significantly

Pichi Picu´n Leufu´ 1993, 1996 1,650 6.613

on the spot market, with energy selling at low prices when conditions were rainy and at high prices when they were dry. Along with climatic conditions that principally affected energy supply, spot market prices also were affected by the level of plants were ENDESA’s forte, so its participation in the

Hidro-economic activity, which determined the demand for energy. nor plants would be very natural. These were also large-sized

As a result, decisions regarding business strategy and contracts plants, permitting a strong expansion in one concentrated effort.

for energy sales by companies with hydroelectric plants were As indicated in Table 7, it would be possible to enter

much more delicate than in the case of thermal plants. bidding for 50, 1,000, 1,320, and 1,650 Mw plants in a very

For hydroelectric business in Argentina, ENDESA formed short period of time. It thus became necessary to establish

a new consortium in which it had 40% ownership, ENDESA-priorities, since by bidding for one of the larger plants in this

Espan˜a had another 40%, and an Argentine company had the third round, ENDESA would be duplicating both its

invest-remaining 20%. ENDESA-Espan˜a was majority state-owned ment its operating potential in Argentina in less than one year.

and had an important presence in the Spanish electric energy The companies described in Table 7 consist of Hidranor

sector. It had 11,550 Mw of installed capacity (between itself plants, both installed and under construction, on the Neuque´n

and its affiliates), of which 2,770 corresponded to hydroelec-and Limay rivers in northern Patagonia. These companies have

tric plants. The consortium agreement stipulated that once been awarded 60-year concessions for use of works and water.

acquired, the operator of the Hidronor plant would be EN-Except for Alicura´, the reservoirs have several objectives:

con-DESA-Chile, in consultation with ENDESA-Espan˜a. Not long trolling flooding or a rise in the volume of water, regulation

before, ENDESA-Espan˜a along with Electricite de France and of river flow for irrigation, and generation of electric energy.

the Argentine company Astra had bid on Edenor, the other Electricity production is subordinate to the other objectives.

distributor of electrical energy in Buenos Aires. In order to assure that these other objectives are met, the

Chilean presence in Argentina was extending into such concession contracts include restrictions on the operation of

varied sectors as supermarkets, shopping centers, consumer reservoirs. To the extent that operating standards are

re-products, steel, copper manufacturing, and other industries. spected, the plant owner is exempt from responsibility for

While Minister Cavallo publicly expressed satisfaction with damages downstream due to floodwaters or drought.

the high level of Chilean investment in the Argentine economy, In the case of plants under construction (Piedra del Aguila

public opinion was sensitive to further Chilean incursions, and Pichi Picu´n Leufu´), the corresponding contracts are

trans-particularly in the privatization process. Nevertheless, EN-ferred. The state will be responsible for the cost of repairing

DESA executives felt their investment would only come under any deficiency in the dams at these facilities.

fire if there were supply problems caused by poor management A tour of inspection at the installations has indicated that

of the companies. In the particular case of the Hidronor plants, electromechanical equipment is in generally good condition.

a special decree was required to permit Chilean investment, The problems of leaking at El Choco´n are being taken care

which would otherwise be prohibited due to the plant’s loca-of, as are problems occurring at the Piedra del Aguila during

tion on the border. Another aspect for consideration was that the filling process.

if ENDESA won a bid on one of the large Hidronor plants, The projects are far away from centers of population, and

almost 25% of the installed capacity in the National Intercon-at some of them personnel live in camps Intercon-at the plant.

nected System would be operated by Chilean companies. Energy produced by these plants is transmitted to the

Bue-Finally, considering the difficulty of administering further nos Aires area along three lines belonging to the transmission

investments in Argentina and the uncertainties surrounding company.

investment in other Latin American countries, another option The installations were not very old, and the concession

for ENDESA was to halt the process of internationalization contract was for 60 years. Electromechanical equipment was

and focus its efforts on Chile in areas where it could exploit well preserved and no heavy initial investment was necessary

its comparative advantages, such as in the operation of public for rehabilitation. There were some difficulties at the El

Cho-concessions or in energy-intensive sectors. However, prelimi-co´n and Piedra del Aguila dams, including the existence of a

nary studies showed that the amount of resources ENDESA provincial agency in charge of managing the watershed and

had available for investment would require the company to reservoirs, which would mean complications concerning

imple-ment the $500 million plan. The other sectors would be, Hidronor hydroelectric plants, which would be awarded in February 1993. The Board members wondered whether it for example, those in which the country had comparative

advantages and the investment required was highly significant, was sound to continue the internationalization strategy in Argentina, whether they should wait for opportunities in other such as wood, cellulose paper, and mining.