Child abuse: Parental mental illness, learning disability,

substance misuse, and domestic violence

Hedy Cleaver

Ira Unell

C h i l d a b u s e : P a r e n t a l m e n t a l i l l n e s s , l e a r n i n g d i s a b i l i t y,

s u b s t a n c e m i s u s e a n d d o m e s t i c v i o l e n c e

2 n d e d i t i o n

H E DY C L E AV E R , I R A U N E L L A N D J A N E A L D G AT E

UTP

xxx/utptipq/dp/vl

Nbjm-!Ufmfqipof-!Gby!'!F.nbjm

QP!Cpy!3:-!Opsxjdi-!OS4!2HO

Ufmfqipof!psefst0Hfofsbm!forvjsjft;!1981!711!6633 Gby!psefst;!1981!711!6644

F.nbjm;!dvtupnfs/tfswjdftAutp/dp/vl Ufyuqipof;!1981!351!4812

UTPACmbdlxfmm!boe!puifs!Bddsfejufe!Bhfout

PublishedfortheDepartmentforEducationunderlicencefromtheControllerof HerMajesty’sStationeryOffice.

Allrightsreserved. ©CrownCopyright2011

Youmayreusethisinformation(excludinglogos)freeofchargeinanyformator medium,underthetermsoftheOpenGovernmentLicence.Toviewthislicence,visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/opengovernmentlicence/

oremail:psi@nationalarchives.gsi.gov.uk.

Wherewehaveidentifiedanythirdpartycopyrightinformationyouwillneedtoobtain permissionfromthecopyrightholdersconcerned.

Thispublicationisalsoavailablefordownloadatwww.officialdocuments.gov.uk ISBN:9780117063655

List of figures and tables vi

Preface vii

Acknowledgements viii

Introduction 1

Researchcontext 1

Legalandpolicycontext 8

Limitationsoftheresearchdrawnoninthispublication 16

Structureofthebook 18

PART I: GENERAL ISSUES AFFECTING PARENTING CAPACITY 21

1 Is concern justified? Problems of definition and prevalence 23

Problemswithterminology 23

Prevalenceofparentswithproblemdrinkingordrugmisuse:general

Summaryoftheevidenceforalinkbetweenparentaldisordersand

Prevalence 27

Prevalenceofparentalmentalillness:generalpopulationstudies 28 Prevalenceofparentallearningdisability:generalpopulationstudies 33

populationstudies 36

Prevalenceofdomesticviolence:generalpopulationstudies 43

childabuse 47

Tosumup 48

2 How mental illness, learning disability, substance misuse and domestic

violence affect parenting capacity 49

Impactonparenting 61

Socialconsequences 74

Tosumup 80

3 Which children are most at risk of suffering significant harm? 85

Whatconstitutessignificantharm? 85

Vulnerablechildren 86

Protectivefactors 90

Tosumup 93

Movingontoexploretheimpactonchildrenatdifferentstagesof

development95

PART II: ISSUES AFFECTING CHILDREN OF DIFFERENT AGES 97

4 Child development and parents’ responses – children under 5 years 99

Prebirthto12months 99

Prebirthto12months–theunbornchild 99

Tosumup 108

Prebirthto12months–frombirthto12months 108

Tosumup 115

Childrenaged1–2years 116

Tosumup 124

Childrenaged3–4years 125

Tosumup 134

Identifieddevelopmentalneedsinchildrenunder5years 135

5 Child development and parents’ responses – middle childhood 137

Childrenaged5–10years 137

Tosumup 155

Childrenaged11–15years 159

Tosumup 179

Childrenaged16yearsandover 180

Tosumup 193

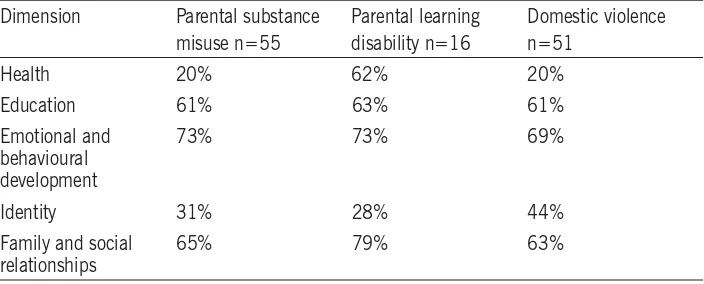

Identifiedunmetdevelopmentalneedsinadolescence 195

PART III: CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY AND

PRACTICE 197

7 Conclusions 199

8 Implications for policy and practice 201

Earlyidentificationandassessment 201

Jointworking 204

Flexibletimeframes 205

Informationforchildrenandfamilies 206

Trainingandeducationalrequirements 207

Tosumup 208

Bibliography 211

Figures

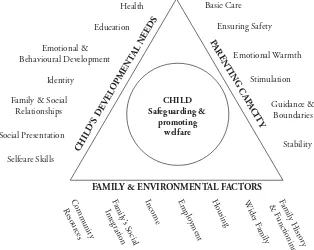

Figure1.1 TheAssessmentFramework Tables

Table1.1 Prevalenceofmentalillnessamongadultsinthegeneralpopulation Table1.2 Prevalenceofmentalillnessamongparentsinthegeneralpopulation Table1.3 Relationshipbetweentherateofrecordedparentalproblemsandthe

levelofsocialworkintervention

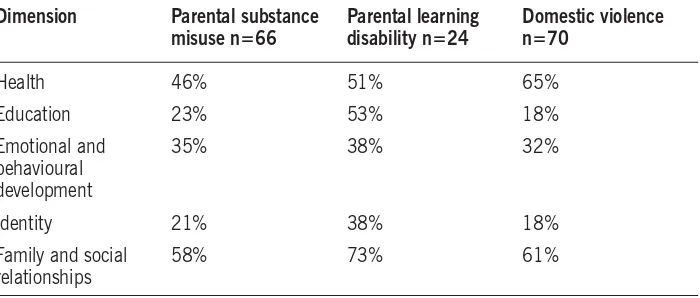

Table4.1 Proportionofchildrenwithidentifiedunmetneeds–childrenunder 5years

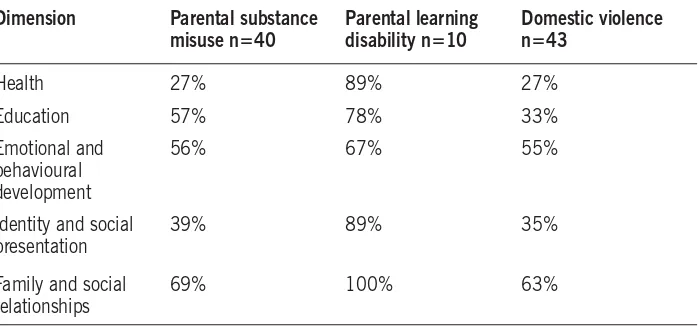

Table5.1 Proportionofchildrenwithidentifiedunmetneeds–middle childhood

Itisprobablytruetosaythat,formostpeople,childhoodisamixedexperience whereperiodsofsadnessandlossarebalancedwithmomentsofhappinessand achievement.Suchcomplexity,however,israrelyrepresentedintheliteratureof childhood.Indeed,muchofthewrittenwordinthenineteenthandtwentieth centuriesdepictschildhoodinoneoftwocontrastingways.Forexample,A.A. Milne’spoem‘IntheDark’,firstpublishedin1927,(Milne1971)showschildhood asagoldenerawherechildrenarelovedandnurturedbycaringparents.Itisa timecharacterisedbyinnocence,unqualifiedparentallove,irresponsibility,peer friendshipsandathirstforadventureandknowledge.

I’vehadmysupper, Andhadmysupper,

AndHADmysupperandall; I’veheardthestory

OfCinderella,

Andhowshewenttotheball; I’vecleanedmyteeth,

AndI’vesaidmyprayers,

AndI’vecleanedandsaidthemright; Andthey’veallofthembeen

Andkissedmelots,

They’veallofthemsaid‘Goodnight.’

Butneverfarawayisthealternativeexperience,typifiedbyparentaldesertion, illness,isolationandpoverty.JamesWhitcombRiley(1920),whopenneduplifting poemsofperhapsquestionablequalityforchildrenduringthe1890s,paintsamuch bleakerpictureinhispoem‘TheHappyLittleCripple’.

I’mthistalittlecrippleboy,an’nevergoin’togrow An’getagreatbigmanatall!–‘causeAuntytoldmeso. WhenIwasthistababyonc’t,Ifalledoutofthebed

An’got“TheCurv’tureoftheSpine”–‘at’swhattheDoctorsaid. IneverhadnoMothernen–fermyParunnedaway

Weacknowledgewithsincerethanksthemanypeoplewhogavegenerouslyoftheir timetohelpuswiththiswork.Weparticularlyappreciatetheexpertiseandadvice offeredbyArnonBentovim,RichardVelleman,LornaTempleton,CarolynDavies andSheenaPrentice.TheworkhasbeenfundedbytheDepartmentforEducation andwethankstaffinthedepartment,particularlyJennyGraywhosupportedus throughouttheworkwithherinterestandvaluablecomments.

Theworkwasassistedbyanadvisorygroupwhosemembershipwas:

ThissecondeditionofChildren’sNeeds–ParentingCapacityprovidesanupdate ontheimpactofparentalproblems,suchassubstancemisuse,domesticviolence, learningdisabilityandmentalillness,onchildren’swelfare.Research,andin particularthebiennialoverviewreportsofseriouscasereviews(Brandonetal2008; 2009;2010),havecontinuedtoemphasisetheimportanceofunderstandingand actingonconcernsaboutchildren’ssafetyandwelfarewhenlivinginhouseholds wherethesetypesofparentalproblemsarepresent.

Almostthreequartersofthechildreninboththisandthe200305studyhadbeen livingwithpastorcurrentdomesticviolenceandorparentalmentalillhealth andorsubstancemisuse–oftenincombination.

(Brandonetal2010,p.112)

Theseconcernswereverysimilartothosethatpromptedthefirsteditionofthis book,whichwascommissionedfollowingtheemergenceofthesethemesfromthe DepartmentofHealth’sprogrammeofchildprotectionresearchstudies(Department ofHealth1995a).Thesestudieshaddemonstratedthatahighlevelofparental mentalillness,problemalcoholanddrugabuseanddomesticviolencewerepresent infamiliesofchildrenwhobecomeinvolvedinthechildprotectionsystem.

Research context

andneglectthatitisdrainingtimeandresourceawayfromfamilies’(Munro2010,p.6). Munro’sInterimReport(2011)drawsattentiononceagaintothehighlytraumatic experienceforchildrenandfamilieswhoaredrawnintotheChildProtectionsystem wheremaltreatmentisnotfound,whichleavesthemwithafearofaskingforhelp inthefuture.Afindingwhichwasidentifiedbyearlierresearchonchildprotection (CleaverandFreeman1995).

Evidencefromthe1995childprotectionresearch(DepartmentofHealth1995a) indicatedthatwhenparentshaveproblemsoftheirown,thesemayadverselyaffect theircapacitytorespondtotheneedsoftheirchildren.Forexample,Cleaverand Freeman(1995)foundintheirstudyofsuspectedchildabusethatinmorethan halfofthecases,familieswereexperiencinganumberofproblemsincludingmental illnessorlearningdisability,problemdrinkinganddruguse,ordomesticviolence.A similarpictureofthedifficultiesfacingfamilieswhohavebeenreferredtochildren’s socialcareservicesemergesfrommorerecentresearch(CleaverandWalkerwith Meadows2004).Itisestimatedthatthereare120,000familiesexperiencing multipleproblems,includingpoormentalhealth,alcoholanddrugmisuse,and domesticviolence.‘Overathirdofthesefamilieshavechildrensubjecttochildprotection procedures’(Munro2011,p.30,paragraph2.30).

Children’sserviceshavethetaskofidentifyingchildrenwhomayneedadditional servicesinordertoimprovetheirwellbeingasrelatingtotheir:

(a) physicalandmentalhealthandemotionalwellbeing; (b) protectionfromharmandneglect;

(c) education,trainingandrecreation;

(d) thecontributionmadebythemtosociety;and (e) socialandeconomicwellbeing.

(Section10(2)oftheChildrenAct2004)

TheCommonAssessmentFramework(Children’sWorkforceDevelopment Council2010)andtheAssessmentFramework(DepartmentofHealthetal.2000) enablefrontlineprofessionalsworkingwithchildrentogainanholisticpictureof thechild’sworldandidentifymoreeasilythedifficultieschildrenandfamiliesmay beexperiencing.Althoughresearchsuggeststhatsocialworkers(Cleaveretal.2007) andhealthprofessionalsareequippedtorecogniseandrespondtoindicationsthata childisbeing,orislikelytobe,abusedorneglected,thereislessevidenceinrelation toteachersandthepolice(Danieletal.2009).

Forrester2009).Acallformorehighqualitytrainingonchildprotectionacross socialcare,healthandpolicewasalsomadebyLordLaming(2009).Munro’s reviewofchildprotectioninexploring‘whypreviouswellintentionedreformshave notresultedintheexpectedlevelofimprovements’(p.3)highlightedthe‘unintended consequencesofrestrictiverulesandguidance’,whichhaveleftsocialworkersfeeling that‘theirprofessionaljudgementisnotseenasasignificantaspectofthesocialwork task;itisnolongeranactivitywhichisvalued,developedorrewarded’(Munro2010, p.30,paragraph2.16).

Theexperienceofprofessionalsprovidingspecialistservicesforadultscan supportassessmentsofchildreninneedlivingwithparentalmentalillness,learning disability,substancemisuseordomesticviolence.Research,however,showsthatin suchcasescollaborationbetweenadults’andchildren’sservicesattheassessment stagerarelyhappens(Cleaveretal.2007;CleaverandNicholson2007)andalack ofrelevantinformationmaynegativelyaffectthequalityofdecisionmaking(Bell 2001).Anagreedconsensusofoneanother’srolesandresponsibilitiesisessential foragenciestoworkcollaboratively.TheevidenceprovidedtotheMunroreview (2011)found‘mixedexperiencesandabsenceofconsensusabouthowwellprofessionals areunderstandingoneanother’srolesandworkingtogether’andarguesfor‘thoughtfully designedlocalagreementsbetweenprofessionalsabouthowbesttocommunicatewith eachotherabouttheirworkwithafamily...’(Munro2011,p.28,paragraph2.23). Althoughresearchshowsthatthedevelopmentofjointprotocolsandinformation sharingproceduressupportcollaborativeworkingbetweenchildren’sandadults’ services(Cleaveretal.2007),asurveyof50Englishlocalauthoritiesfoundonly 12%hadclearfamilyfocusedpoliciesorjointprotocols(CommunityCare2009).

Themultiagencyapproach

Inmanyofthecasesthatarereferredtochildren’ssocialcare,nosingleagencywill beabletoprovideallthehelprequiredtosafeguardandpromotethewelfareof thechildandmeettheneedsoftheirparents.Socialworkers,inpartnershipwith familiesandotheragencies,mustjudgewhatservices,fromwhichagencies,are calledfor.Aresearchbasedtypologyoffamilieshasbeendevelopedtohelpsocial workersidentifytherange,typeanddurationofservicesrequiredtomeettheneeds ofthechildandsupportthefamily(CleaverandFreeman1995).Threecategories inthetypologyareparticularlyrelevant:

エ!

Families experiencing multiple problems: thesefamiliesarewellknownto

エ!

Families experiencing a specific problem: thesefamiliesarerarelyknownto statutoryagenciesandcometotheirattentionbecauseofaspecificissue,for exampleacuteparentalmentalillnessoraparentaldrugoverdose.Families arenotconfinedtoanysocialclassand,onthesurfacetheirlivesmayappear quiteordered.エ!

Acutely distressed families: thesefamiliesnormallycope,butanaccumulationofdifficultieshasoverwhelmedthem.Familiestendtobecomposedofsingle orpoorlysupportedandimmatureparents,orparentswhoarephysicallyill ordisabled.

Theabovetypologymakesacleardistinctionbetweenfamilieswhonormallycope wellbuthavebeenrecentlyoverwhelmedbyproblemsandthosewhohavemany chronicproblemswhichrequirelongtermmultiserviceinput.Toensurechildren’s safetyandwelfare,manyofthesefamilieswillrequiresupportfrombothchildren’s andadults’services.Acollaborativeapproachwouldensurethatnotonlyareparents recognisedashavingneedsintheirownright,buttheimpactofthoseneedson theirchildrenbecomespartofamultiagencyresponse.Researchsuggeststhatthe valueofsuchinteragencycollaborationiswidelyacceptedbyprofessionals(Cleaver etal.2007).AreviewoftheliteratureonneglectbyDanielandcolleagues(2009) highlightedtheimportanceofdevelopingmoreeffectiveintegratedapproaches tochildrenwhereallprofessionsregardthemselvesaspartofthechildwellbeing system.However,ensuringthatpracticereflectstheseprinciplesisnotalwayseasy, despitethesupportofnationalpolicyandguidance.

Despiteconsiderableprogressininteragencyworking,oftendrivenbyLocal SafeguardingChildrenBoardsandmultiagencyteamswhostrivetohelpchildren andyoungpeople,thereremainsignificantproblemsinthedaytodayrealityof workingacrossorganisationalboundariesandcultures,sharinginformationto protectchildrenandalackoffeedbackwhenprofessionalsraiseconcernsabouta child.

(LordLaming2009,p.10,paragraph1.6)

Theimportanceofanintegratedprofessionalgroupbeingaccountableforlocal childprotectionratherthanconfiningtheresponsibilitytochildren’ssocialcarewas stressedinMunro’sfirsttworeportsonthechildprotectionsystem(2010,2011).

Reluctancetoadmitproblems

insocialworkerstakingpunitiveaction.Subsequentresearchreinforcesthisfinding (see,forexample,BoothandBooth1996;Cleaveretal.2007;Gorin2004).

Forsimilarreasons,familieswereeagertoconcealdomesticviolence.Farmer andOwen’s(1995)researchsuggests,firstly,thathiddendomesticviolencemay accountformanymothers’seeminglyuncooperativebehaviourand,secondly, thatconfrontingfamilieswithallegationsofabusecouldcompoundthemother’s vulnerableposition.Indeed,childprotectionconferenceswereoftenignorantof whetherornotchildrenlivedinviolentfamiliesbecauseinthe‘faceofallegations ofmistreatmentcouplesoftenformedadefensiveallianceagainsttheoutsideagencies’

(FarmerandOwen1995,p.79).Infact,theauthorsfoundthatthelevelofdomestic violence(52%)discoveredduringtheresearchinterviewswastwicethatdisclosed attheinitialchildprotectionconference.‘Problemswhichparentsthoughtwouldbe discreditingwerenotairedintheearlystages–especiallythosewhichincludeddomestic violenceandalcoholanddrugabuse’(FarmerandOwen1995,p.190).

Thefearthatchildrenwillbetakenintocareandfamiliesbrokenupifparental problemscometolightmaybefeltmoreacutelywhenthemotherisfroma minorityethnicgroup.Difficultiesincommunicationandworriesovercultural normsbeingmisinterpretedincreasewomen’sfears,andofficialagenciesmaybe seenasparticularlythreateningifthemotherisofrefugeestatus(Stevenson2007). Parentsvalueprofessionalswhoarenonjudgementalintheirapproach,who communicatesensitivelyandwhoinvolvetheparentsandkeeptheminformed duringallstagesofthechildprotectionprocess(CleaverandWalkerwithMeadows 2004;KomulainenandHaines2009).Evidencesuggeststhatparentsareableto discusstheirownconcernsabouttheirparentingwhenprofessionalsapproachthem openlyanddirectly(Danieletal.2009).Unfortunately,manyparentsfeeltheyare treatedlesscourteouslybymedicalstaffonceconcernsofnonaccidentalinjuryare raised(KomulainenandHaines2009).

Workinginpartnershipwithchildrenandkeyfamily

members

Statutoryguidance,producedforprofessionalsinvolvedinassessmentsofchildren inneedundertheChildrenAct1989,acknowledgestheimportanceofinvolving childrenandfamiliesandseekstoensurethatallphasesoftheassessmentprocessare carriedoutinpartnershipwithkeyfamilymembers.

Thequalityoftheearlyorinitialcontactwillaffectlaterworkingrelationships andtheabilityofprofessionalstosecureanagreedunderstandingofwhatis happeningandtoprovidehelp.

(DepartmentofHealthetal.2000,p.13,paragraph1.47)

involvementinassessments,plansandreviews.Researchshowsthatmanysocial workersgotoconsiderablelengthstoexplainthingstoparents(particularlythose withlearningdisabilities)andchildren,andtoinvolvethemasmuchaspossiblein allstagesofthechildprotectionprocess(CleaverandWalkerwithMeadows2004). Asecondfindingisthatprofessionalstendtoevadefrighteningconfrontations;a featurewhichcontinuestobeidentifiedinseriouscasereviews(Brandonetal.2009, 2010;DepartmentforEducation2010c;LordLaming2009).Researchsuggests thatwhenprofessionalsfeelunsupportedormustvisitalone,visitingandchild protectionenquiriesmightnotalwaysbeasthoroughastheycouldbe(James1994; Denny2005;Farmer2006).

Gender

Fewofthe1995childprotectionstudiesexploredparentalproblemsintermsof genderandwhetherthegenderoftheparentwiththeprobleminfluencedsocial workintervention.Irrespectiveofwhichparentalfigurewaspresentingtheproblem, professionalsfocusedtheirattentiononworkingwithmothers.Insomecases, despiteprolongeddomesticviolencedirectedfromafatherfiguretothemother andsuspicionsthatthemanwasalsophysicallyabusivetothechildren,fatherswere rarelyinvolvedinthechildprotectionwork.‘Theshiftoffocusfrommentowomen allowedmen’sviolencetotheirwivesorpartnerstodisappearfromsight’(Farmer2006, p.126).However,forsomefamiliesthepossibilityofsocialworkersengagingwith thefatherfigurewasdifficultbecauseherefusedtodiscussthechildwiththeworker, wasalwaysoutduringsocialworkvisitsornolongerlivedinthehousehold(Farmer 2006).

Interpretingbehaviour

Afinalfactoridentifiedbytheoriginalchildprotectionstudies,andstillpertinent today,isthatsocialworkersmaymisinterpretparents’behaviour(Departmentfor Education2010c;HMGovernment2010a;C4EO2010).Forexample,research hasshownthatsocialworkerswerelikelytoassumethatguiltyorevasivebehaviour ofparentswasrelatedtochildabuse.Butsuchbehaviourwas,onoccasions,found tobetheresultofparentswantingtokeepsecretahistoryofmentalillness,learning disability,illicitdruguseorotherfamilyproblems(CleaverandFreeman1995).

2010c).Professionals’sympathyforparentscanleadtoexpectationsforchildren beingsettoolow.LordLamingstresses,‘Itisnotacceptabletodonothingwhenachild maybeinneedofhelp.Itisimportantthatthesocialworkrelationship,inparticular,isnot misunderstoodasbeingarelationshipforthebenefitoftheparents,orfortherelationship itself,ratherthanafocusedinterventiontoprotectthechildandpromotetheirwelfare’

(LordLaming2009,p.24,paragraph3.2).Practitionersupportwhichbenefits theparentsbutdoesnotpromotethewelfareofthechildrenwasalsoaconcern highlightedinMunro’sfirstreportofthechildprotectionsystem.Sheidentified‘a reluctanceamongmanypractitionerstomakenegativeprofessionaljudgmentsabouta parent....Incaseswhereadultfocusedworkersperceivedtheirprimaryroleasworking withintheirownsector,failuretotakeaccountofchildreninthehouseholdcouldfollow’

(Munro2010,p.17,paragraph1.27).Akeyfindingfromareviewofevidenceon whatworksinprotectingchildrenlivingwithhighlyresistantfamilieswastheneed forauthoritativechildprotectionpractice.

Families’lackofengagementorhostilityhamperedpractitioners’decisionmaking capabilitiesandfollowthroughwithassessmentsandplans...practitioners becameoverlyoptimistic,focusingtoomuchonsmallimprovementsmadeby familiesratherthankeepingfamilies’fullhistoriesinmind.

(C4EO2010,p.2)

Alackofknowledgeaboutdifferentcultureswithinminoritycommunities canalsobeabarriertounderstandingwhatishappeningtothechildren.Inquiry reportsandresearchhavehighlightedthatstereotypingoffamiliesfromdifferent backgrounds,linkedwithdifficultiesinattributingthecorrectmeaningtowhat parentssay,mayhaveanegativeimpactonsocialworkassessmentsandjudgements (DuttandPhillips2000).Forexample,inthecaseofVictoriaClimbié,achildwho cametoEnglandfromtheIvoryCoastofAfrica,professionalsassumedtheunusual, exceptionallyrespectfulandfrequentlyfrozenresponsetoher‘mother’wasnormal inthefamily’sculture,wheninfactitwasasignthatVictoriawasafraidofher abusivecarer(Cm57302003;ArmitageandWalker2009).Communicationand understandingcanbeeasedwhenparentshavetheopportunitytousethelanguage oftheirchoice(GardnerandCleaver2009).Thefollowingconclusion,drawnfrom analysingchilddeathsandseriousinjury,isrelevanttoallthoseprofessionalswho haveconcernsaboutthewelfareandsafetyofachild.

Inordertohaveabetterchanceofunderstandinghowdifficultiesinteract, practitionersmustbeencouragedtobecurious,andtothinkcriticallyand systematically.

Legal and policy context

Safeguardingandpromotingchildren’swelfare

TheChildrenAct1989placesadutyonlocalauthoritiestoprovidearangeof appropriateservicesforchildrentoensurethatthose‘inneed’aresafeguardedand theirwelfareispromoted.Childrenaredefinedas‘inneed’whentheyareunlikely toreachormaintainasatisfactorylevelofhealthordevelopment,ortheirhealth anddevelopmentwillbesignificantlyimpairedwithouttheprovisionofservices (s17(10)oftheChildrenAct1989).

Althoughmanyfamiliescopeadequatelywiththedifficultiestheyface,others needtheassistanceofservicesandsupportfromoutsidethefamilyto‘safeguardand promotethewelfareofthechildren’,whichisdefinedas:

エ!

protectingchildrenfrommaltreatment;

エ!

preventingimpairmentofchildren’shealthordevelopment;

エ!

ensuringthatchildrenaregrowingupincircumstancesconsistentwiththe provisionofsafeandeffectivecare;

andundertakingthatrolesoastoenablethosechildrentohaveoptimumlife chancesandtoenteradulthoodsuccessfully.

(HMGovernment2010a,p.34,paragraph1.20)

TheDepartmentofHealth‘regardssafeguardingvulnerablechildrenasahigh priorityandissupportingtheNHStoimprovesafeguardingarrangements’(Department ofHealth2010a,p.6).Providingsupporttoparentsinordertoimproveoutcomesfor childrenispartoftheGovernment’sstrategytoimprovepublichealth.IntheWhite PaperHealthyLives,HealthyPeople(Cm79852010)theGovernmentseekstogive

evidence‘tosuggestthatthefirstthreeyearsoflifecreatethefoundationinlearninghow toexpressemotionandtounderstandandrespondtotheemotionsofothers’(Allen2011, p.5,paragraph15).Thereisanemphasisonearlyinterventionpackageswhich haveaproventrackrecord,andarecommendationthatanew,EarlyIntervention Foundationiscreated.

Pastgovernmentshavealsosoughttorespondtotheneedsofvulnerablefamilies withtheaimofimprovingthewellbeingofchildren.TheChildrenAct1989 recognisedthattopromotechildren’swelfare,servicesmayneedtoaddressthe difficultiesthatparentsexperience.

Parentsareindividualswithneedsoftheirown.Eventhoughservicesmaybe offeredprimarilyonbehalfoftheirchildren,parentsareentitledtohelpand considerationintheirownright...Theirparentingcapacitymaybelimited temporarilyorpermanentlybypoverty,racism,poorhousingorunemploymentor bypersonalormaritalproblems,sensoryorphysicaldisability,mentalillnessor pastlifeexperiences...

(DepartmentofHealth1991,p.8)

UndertheChildrenAct2004‘achildren’sservicesauthorityinEnglandmusthave regardtotheimportanceofparentsandotherpersonscaringforchildreninimproving thewellbeingofchildren’(Section10(3)oftheChildrenAct2004).

TheNationalFrameworkforChildren,YoungPeopleandMaternityServices stressedtheimportanceofprovidingsupporttoparentsandtheneedforcollaboration betweenadults’andchildren’sservices.

Inadditiontomeetingthegeneralneedsofparentsfromdisadvantaged backgrounds,itisimportanttoconsiderthemorespecialisedformsofsupport requiredbyfamiliesinspecificcircumstances,suchassupportforparentswith mentalhealthdifficultiesordisabilities,orwithsubstancemisuseproblems.Good collaborativearrangementsarerequiredbetweenservicesforadults,wherethe adultisaparent,andchildren’sservices,inparticular,wherechildrenmaybe especiallyvulnerable.

(DepartmentofHealthandDepartmentforEducationandSkills2004, p.69,paragraph3.4).

TheneedsofvulnerablechildrenwereaddressedintheDepartmentofHealth’s revisedcodeofpracticewhichprovidesguidancetodoctors,relevanthospitalstaff andmentalhealthprofessionalsonhowtheyshouldproceedwhenundertaking theirdutiesundertheMentalHealthAct1983.Thecodeofpracticenotesthat practitionersshouldensurethat:

エ!

appropriatearrangementsareinplacefortheimmediatecareofdependent children;

エ!

thebestinterestsandsafetyofchildrenarealwaysconsideredin arrangementsforchildrentovisitpatientsinhospital;and

エ!

thesafetyandwelfareofdependentchildrenaretakenintoaccountwhen cliniciansconsidergrantingleaveofabsenceforparentswithamental disorder.

(DepartmentofHealth2008)

Improvingchildprotectionandreformingfrontlinesocialworkpracticeis apriorityfortheGovernment.Althoughpastgovernmentswerecommittedto protectingchildren,statisticalreturnsonthenumbersofchildrensubjecttoachild protectionplancontinuetoincreasesuggestingmoreneedstobedone(Department forEducation2009and2010a).AtMarch201039,100childrenweresubjecttoa childprotectionplan,anincreaseof5,000(15%)fromthe200809figures(Munro 2011,p.25).Threeprinciplesunderpinnedtherecentreviewofchildprotection whichtheGovernmentaskedProfessorMunrotoundertake:‘earlyintervention; trustingprofessionalsandremovingbureaucracysotheycanspendmoreoftheirtimeon thefrontline;andgreatertransparencyandaccountability’(Munro2010,p.44).

TheChildrenAct2004placedstatutorydutiesonlocalagenciestomake arrangementstosafeguardandpromotethewelfareofchildreninthecourseof dischargingtheirnormalfunctions.Ensuringeffectiveinteragencyworkingisa keyresponsibilityofLocalSafeguardingChildrenBoards(LSCBs).LSCBsshould ensurethatagenciesdemonstrategoodcollaborationandcoordinationincases whichrequireinputfrombothchildren’sandadults’services.Servicesforadults includeGPsandhospitals,learningdisabilityandmentalhealthteams,drugaction teamsanddomesticviolenceforums.

Asurveyoftheorganisationsresponsibleforsafeguardingandpromotingthe welfareofchildrenundersection11oftheChildrenAct2004suggestedthat althoughsignificantprogresshasbeenmade,twothirdsoforganisationsdidnotyet haveallthekeyarrangementsinplace(MORI2009).TheGovernment’sstatutory guidanceWorkingTogethertoSafeguardChildrenmakesclearthatsafeguardingand promotingthewelfareofchildren‘dependsoneffectivejointworkingbetweenagencies andprofessionalsthathavedifferentrolesandexpertise’(HMGovernment2010a, p.31,paragraph1.12).

Adultmentalhealthservices–includingthoseprovidinggeneraladultand community,forensic,psychotherapy,alcoholandsubstancemisuseandlearning disabilityservices–havearesponsibilityinsafeguardingchildrenwhenthey becomeawareof,oridentify,achildatriskofharm.

Parentalmentalillness

TheGovernmentiscommittedto

‘protectingthepopulationfromserioushealththreats;helpingpeoplelivelonger, healthierandmorefulfillinglives;andimprovingthehealthofthepoorest,fastest; andliftingfamiliesoutofpoverty.’

(Cm79852010,p.4(1))

Poormentalhealthisakeycomponentoftheoverallburdenoflongstanding illnesswithinthegeneralpopulationandisresponsibleforthegreatestproportionof workingdayslost(HealthandSafetyExecutive2010).Initsstrategyforimproving publichealthinEngland,theGovernmenthasidentifiedtheneedtotargetarange ofissuesincludingmentalillness,heavydrinkinganddrugmisuse(Cm79852010). Itrecognisesthatnosingleagencycandothisalone.‘Responsibilityneedstobeshared rightacrosssociety–betweenindividual,families,communities,localgovernment, business,theNHS,voluntaryandcommunityorganisations,thewiderpublicsectorand centralgovernment’(Cm79852010,p.24,paragraph2.5).TheCrossGovernment mentalhealthoutcomesstrategysetsoutplanstoensurementalhealthawareness andtreatment(forchildrenaswellasadults)aregiventhesameprominenceas physicalhealth.Sixobjectivesarehighlighted:

(i) Morepeoplewillhavegoodmentalhealth

(ii) Morepeoplewithmentalhealthproblemswillrecover

(iii) Morepeoplewithmentalhealthproblemswillhavegoodphysicalheath (iv) Morepeoplewillhaveapositiveexperienceofcareandsupport

(v) Fewerpeoplewillsufferavoidableharm

(vi) Fewerpeoplewillexperiencestigmaanddiscrimination

(HMGovernment2011,p.6,paragraph1.5)

Childrenareattheheartofthisstrategy.Itacknowledgesthatsomeparents‘will requireadditionalsupporttomanageanxietyanddepressionduringpregnancyandthe child’searlyyears...’(HMGovernment2011,p.39,paragraph5.5).Theaimisto interveneearlywith‘vulnerablechildrenandyoungpeopleinordertoimprovelifetime healthandwellbeing,preventmentalillnessandreducecostsincurredbyillhealth, unemploymentandcrime’(p.9,paragraph1.15).Itisanticipatedearlyintervention willbringbenefitsnotonlytotheindividualduringchildhoodandintoadulthood, butalsoimprovehisorhercapacitytoparent.

‘Goodpartnershipworkingbetweenhealthandsocialcareisvitalforhelpingthemtomanage theirconditionandliveindependently’(DepartmentofHealth2010b,p.13,paragraph 3.13).

Parentswithalearningdisability

TheEqualityAct2010prohibitsserviceprovidersdiscriminatingonanumberof criteriaincludingdisability.Disabilityisdefinedinthefollowingway.

(1)Aperson(P)hasadisabilityif—

(a)Phasaphysicalormentalimpairment,and

(b)theimpairmenthasasubstantialandlongtermadverseeffectonP’s

abilitytocarryoutnormaldaytodayactivities.

(Section6(1)oftheEqualityAct2010)

Section47(1)oftheNationalHealthServicesandCommunityCareAct1990 placesadutyonlocalauthoritiestoconsidertheneedsofdisabledpersons,including thosewithlearningdisabilities.Thisissupportedbypracticeguidance.

Ingeneral,councilsmayprovidecommunitycareservicestoindividualadults withneedsarisingfromphysical,sensory,learningorcognitivedisabilities,or frommentalhealthneeds.

(DepartmentofHealth2010b,p.18,paragraph43)

Supportingdisabledadultsintheirroleasparentsishighlightedinthispractice guidance.Forexample,indeterminingeligibility,allfourlevelsincludethesituation inwhich‘familyandothersocialrolesandresponsibilitiescannotorwillnotbe undertaken’(DepartmentofHealth2010b,p.20,paragraph54).Localauthorities areenjoinedtoconsidertheadditionalhelpthoseadultswith,forexample, mentalhealthdifficultiesorlearningdisabilitiesmayneediftheyhaveparenting responsibilities.Thisincludesidentifyingwhetherachildoryoungpersonisacting inacaringroleandtheeffectthisishavingonthemandexploringwhetherthereis aneedtosafeguardandpromotethewelfareofthechild.

Parentalsubstancemisuse

IntheGovernment’sdrugstrategy,theimpactofdrugsandalcoholmisuseonsociety isrecognised.

Fromthecrimeinlocalneighbourhoods,throughfamiliesforcedapartby dependency,tothecorruptingeffectofinternationalorganisedcrime,drugshave aprofoundandnegativeeffectoncommunities,familiesandindividuals.

(HMGovernment2010b,p.3)

interveningearlyandsupportingpeopletorecover.Relevantagenciesareexpectedto worktogethertoaddresstheneedsofthewholeperson.Topreventsubstancemisuse amongstchildrenandyoungpeople(someofwhomwillhaveparentswhomisuse drugsandalcohol)thestrategyadvocatestheuseoffamilyfocusedinterventions (HMGovernment2010b,p.11).

Ithasbeenestimatedthattherearebetween250,000and350,000childrenof problemdrugusersintheUK(AdvisoryCouncilontheMisuseofDrugs2003) andathirdofadultsintreatmenthavechildcareresponsibilities(HMGovernment 2010b).TheGovernment’sdrugstrategyplacesaparticularfocusonthechildrenof parentswithdrugandalcoholproblems.Theneedtobeawareoftheharm,abuse andneglect,aswellastheinappropriatecaringroles,somechildrenmayexperience isstressed.Thestrategyisclearthat‘wherethereareconcernsaboutthesafetyand welfareofchildren,professionalsfrombothadultandchildren’sservices,alongside thevoluntarysector,shouldworktogethertoprotectchildren,inaccordancewiththe statutoryguidanceWorkingTogethertoSafeguardChildren(2010)’(HMGovernment 2010b,p.21).

Arangeofrelevantpracticeguidanceisavailabletolocalauthorities.Forexample, theDepartmentofHealthhasproducedguidancewhichfocusesonpeoplewith severementalhealthproblemsandproblematicsubstancemisuse.

Substancemisuseisusualratherthanexceptionalamongstpeoplewithsevere mentalhealthproblemsandtherelationshipbetweenthetwoiscomplex.

(DepartmentofHealth2002,p.4)

Theguidancesupportedjointworkingandimprovedcoordinatedcarebetween mentalhealthservicesandspecialistsubstancemisuseservices(Departmentof Health2002).

ModelsofCareforAlcoholMisusers(DepartmentofHealthandNational TreatmentAgencyforSubstanceMisuse2006)providedpracticeguidancefor localhealthorganisationsandtheirpartnersinthecommissioningandprovisionof assessments,interventionsandtreatmentofadultswhomisusealcohol.Theguidance acknowledgedtheimpactofparentalalcoholmisuseonchildren.Thisisclearly statedintheforewordbythethenchiefmedicalofficer,SirLiamDonaldson:

Thereisnodoubtthatalcoholmisuseisassociatedwithawiderangeofproblems, includingphysicalhealthproblemssuchascancerandheartdisease;offending behaviours,notleastdomesticviolence;suicideanddeliberateselfharm;child abuseandchildneglect;mentalhealthproblemswhichcoexistwithalcohol misuse;andsocialproblemssuchashomelessness.

However,therecommendationsrelatingtoscreeningandearlyassessmentsdid notincludethechildrenofparentswhomisusealcohol,althoughtheguidancedid recommendthatcomprehensiveriskassessmentsshouldbetargetedat,amongothers, userswithcomplexneedsincludingwomenwhoarepregnantorhavechildren‘at risk’.TheDepartmentofHealthhasrecentlytrialledarangeofalcoholscreening andbriefinterventionapproachestoevaluatetheirdelivery,effectivenessandcost effectiveness(ScreeningandInterventionProgrammeforSensibleDrinking(SIPS) seewww.hubcap.org.uk/F25W.)

Domesticviolence

TheGovernmentisalsoconcernedaboutviolenceagainstwomenandchildren andiscommittedtoimprovingthestandardsofcareandsupport.

Aswellasthegovernment’scommitmenttosupportexistingrapecrisiscentre provisiononastablebasisandtoestablishnewcentres,theHomeOfficehas allocatedaflatcashsettlementofover£28moverthenextfouryearsforworkto tackleviolenceagainstwomenandgirls.

(HMGovernment2010c,p.15,paragraph2.1)

TheDepartmentofHealth’sactionplanImprovingservicesforwomenandchild victimsofviolence(HMGovernment2010c,p.15,paragraph2.1)ispartofthe crossGovernmentapproachtotacklingsuchviolence.Theplanacknowledgesthat

‘violenceandabusecanalsobeariskfactorinfamilieswithmultipleproblems....the SpendingReviewmakesacommitmentforanationalcampaigntosupportandhelpturn aroundthelivesoffamilieswithmultipleproblems,improvingoutcomesandreducing coststowelfareandpublicservices’(p.10).

Withtheaimofimprovingtheresponsetothevictimsofviolence,theGovernment’s actionplanproposesto:

エ!

raiseawareness:amongsthealthprofessionaloftheirroleinaddressingthe issues,andthroughprovidingpatientswithinformationthathelpsthem accessrelevantservicesquicklyandsafely;

エ!

improvethecompetencyandskillsofNHSstaffthroughdevelopinga trainingmatrix;

エ!

improvethequalityofservicestovictimsofviolence;and

エ!

improvethedatacollectiononviolenceandsupporthealthprofessionalsto appropriatelyshareinformation.

FamilyLawAct1996andtheProtectionfromHarassmentAct1997.The2004 Actextendedthepowersofthecourtinprotectingthepartnersinarelationship. Furthermore,itcreatedanewcriminaloffenceof‘causingorallowingthedeathofa childorvulnerableadult’(Section4oftheDomesticViolence,CrimeandVictims Act2004).

Section24oftheCrimeandSecurityAct2010alsoseekstoprotectwomen andchildrenwhoarethevictimsofdomesticviolence.Seniorpoliceofficershave beengiventhepowertoissuedomesticviolenceprotectionnotices(DVPN).Such anoticecanbeusedtobanviolentmenfromthefamilyhome,initiallyfor24 hours,topreventwomenfromfutureviolenceorthethreatofviolence.Thesafety ofthechildmustalsobetakenintoconsideration.BeforeissuingaDVPNthe officermustconsider‘thewelfareofanypersonundertheageof18whoseintereststhe officerconsidersrelevanttotheissuingoftheDVPN(whetherornotthatpersonisan associatedperson)’(Section24(3)oftheCrimeandSecurityAct2010).Theissuing ofaDVPNtriggerstheapplicationtothemagistratescourtforadomesticviolence protectionorder.Thisisanorder,lastingbetween14and18days,whichprohibits theperpetratorfrommolestinghisvictim.

Thereisalsostatutoryandpracticeguidanceavailabletosupportprofessionalsin safeguardingwomenandchildrenfromdomesticviolence.Forexample,Working TogethertoSafeguardChildrenreinforcedtheroleofthepoliceinidentifyingand safeguardingchildrenlivingwithdomesticviolence;‘patrolofficersattendingdomestic violenceincidents,forexample,shouldbeawareoftheeffectofsuchviolenceonany childrennormallyresidentwithinthehousehold’(HMGovernment2010a,p.71, paragraph2.126).Toensurepoliceofficersworkinginchildprotectionatalllevels haveaccesstospecialisttrainingondomesticviolence,anupdatedtrainingmodule hasbeenmadeavailabletopoliceforcessinceDecember2009(Cm7589).

The2009HomeOfficeguidanceandpracticeadviceandWorkingTogetherto SafeguardChildren(HMGovernment2010a)bothadvocatetheuseofmulti agencyriskassessmentconferences(MARAC)asaprocessfor‘helpingtoaddress anissueofdomesticviolence;formanagingPPOs,includingthosewhoareproblematic drugusers;orforidentifyingchildrenatrisk’(HomeOffice2009a,p.1415,paragraph 2.3.3).(PPOsrefertoProlificandotherPriorityOffenders).MARACmeetingsare expectedtoinvolverepresentativesofkeystatutoryandvoluntaryagencies,who mightbeinvolvedinsupportingavictimofdomesticabuse.

Anotherexampleofmultiagencyworkingincasesofdomesticviolenceisthe SpecialistDomesticViolenceCourt(SDVC)programme.Thesespecialcourts, withintheCriminalJusticeSystem,bringtogetherasimilarrangeofbodiesto MARAC.

Agenciesworktogethertoidentify,trackandriskassessdomesticviolencecases, supportvictimsofdomesticviolenceandshareinformationbettersothatmore offendersarebroughttojustice.

Limitations of the research drawn on in this

publication

Differentlawsandcultures

Muchoftheresearchonmentalillness,learningdisability,domesticviolenceand substancemisusecomesfromtheUS,whichhasdifferentlaws,traditions,andsocial institutionsfromtheUnitedKingdom.Forexample,amajordifferencewhich existsinrelationtosubstancemisuseisthecommitmenttoharmminimisation intheUnitedKingdom.ThisapproachisnotuniversallysharedintheUS,which hasfollowedanabstinenceonlypolicyforthelast30years.Asaresultthereare uniqueservicesintheUnitedKingdom,suchasconsistentlyavailablemethadone treatmentandneedleandsyringeexchangeschemesforproblemdrugusers,and controlleddrinkingprogrammesforproblemalcoholusers.IntheUS,abstinence basedprogrammes,especiallyinalcoholservices,aremoreavailablethancontrolled drinking,andmethadonemaintenanceprogrammesaremorerestrictiveintheUS comparedtotheUnitedKingdom.Thishasimplicationsforservicesforwomenin theUS,wheremanytreatmentprogrammesforpregnantdrugandalcoholusers requirewomentobeabstinentinordertotakepartintheprogramme.Inmany Americanstates,pregnantmotherswhousedrugsoralcoholriskprisonsentences whilepregnantonthegroundsofphysicalchildabuse.

Focusingonaspecificissue

Mostresearchiscentredonaspecificissuesuchasdomesticviolence,depression, learningdisabilityorheroinuse.However,inpractice,manyproblemdruguserswill useavarietyofdrugsandalcohol(polydruguse).Similarly,manyofthoseexperiencing domesticviolencealsosufferdepressionandmayusealcoholordrugsasawayof coping;orthosewhoareperpetratingtheviolencemaybeundertheinfluenceof alcoholordrugs.Moreover,alearningdisabilitydoesnotinureanindividualto drugmisuse,domesticviolenceormentalillness.Inthispublication,althougheach issueistakenindividuallywhendescribingthepsychologicalandphysicalsymptoms, whendiscussingthefindingsfromresearchinrelationtotheimpactonparenting capacityamorepragmaticandinclusiveapproachhasbeentaken.

Timelimitedresearch

Samplingbias

Thesamplesusedinmanyresearchstudiesaretakenfromspecificgroupssuch asparentalcocaineoralcoholusersintreatment,mentallyillparentsinhospital, parentsinreceiptofservicesforlearningdisability,ormothersinrefuges.Farlessis knownaboutparentsinthegeneralpopulationwhoexperiencetheseproblemsbut donotseekhelp;itwouldbedangeroustoassumethatthepopulationsstudiedare representative.

Researchontheimpactofparentalproblemsonchildrentendstobebiased towardswomenascarers.Therearemorestudiesonmaternalparentingcapacity thanpaternalcapacity,andoftentheinfluenceofotherfamilyfactors,suchas theroleofgrandparentsorsiblings,ortheimpactofdivorceorseparation,isnot considered.

Manyofthestudiesfocusonspecificproblems,suchaschildren’sdrugandalcohol use,violence,mentalhealth,education,offendingandbehaviouralproblems,rather thanamoreholisticapproachortheidentificationofsignsofresilienceorcoping strategies.

Itisoftennotpossibletoaccuratelymeasurethequantitiesofdrugsandalcohol beingusedbyparents,thedegreeofviolenceexperienced,ortheextentofmental illnessorlearningdisability.Forexample,someparentsmayfeelthreatenedby serviceswhichcantakeactiononthecareoftheirchildrenandunderestimate theirdifficulties.Inothersituationsparentsmayoverestimatetheirproblems.For example,drugusemaybeexaggeratedandpresentedasmitigatingcircumstancesin criminalcourtcasesorinanattempttomaximiseamethadoneprescription.

Afurtherlimitationoftheresearchisthedependenceonclientrecall.Drugs andalcohol,domesticviolence,mentalillnessandlearningdisabilitiesalladversely affectthecapacitytoremember,andmanystudiesrelynotonlyonrecentmemory butmemoryovermanymonthsoryears.Itisquestionablehowaccuratethese measurementsare.Finally,itisessentialtorememberthatthemajorityofparents whoexperiencetheseissues,especiallythosewhopresentforservices,areusually alsosufferingfrommultipleformsofdeprivationandsocialexclusion.Thesefactors shouldnotbeunderestimatedintheirneteffectonparentingcapacity.

CHILD’S DE VEL

OPMENT AL NEEDS

PARENTING CAP

ACIT

Y CHILD

Safeguarding & promoting

welfare

Health BasicCare

EnsuringSafety

EmotionalWarmth

Stimulation Education

BehaviouralDevelopment

FAMILY & ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS

Emotional&

Identity

Family&Social Guidance&

Relationships Boundaries

SocialPresentation

Stability

SelfcareSkills

Community R

esour

ces

Family

’sS ocial Integration Income

Emplo

yment H

ousing WiderF

amily FamilyH

istor y &F

unctioning

Structure of the book

Inconsideringhowparentalmentalillness,learningdisability,problemdrinking, drugmisuseordomesticviolencemayaffectthechild,aholisticanddevelopmental modelisapplied.Researchfindingsaredisaggregatedthroughapplyingthe conceptualframeworkdesignedtoassessandmeasureoutcomesforchildreninneed (DepartmentofHealthetal2000).Thethreedomainsofthechild’sdevelopmental needs,parentingcapacityandfamilyandenvironmentalfactorsconstitutethe framework.Thethreeinterrelateddomainsincorporateanumberofimportant dimensions(seeFigure1.1).

Figure1.1�eAssessmentFramework

particularemphasisonhowparentalmentalillness,learningdisabilities,substance misuseanddomesticviolencehaveanimpactonchildren’shealthanddevelopment, andwhetherthereisevidencethatchildrenaresuffering,orlikelytosuffer,significant harm.Becausetheimpactonthechildwilldependonavarietyoffactorsincluding ageanddevelopmentalstage,theagebandsfirstusedintheIntegratedChildren’s System(DepartmentforChildren,SchoolsandFamilies2010)havebeenapplied. Forexample,withregardtotheeducationaldevelopmentofchildrenaged3–4years, itisimportanttoidentifywhenparents’problemssubstantiallyrestrictthechild’s accesstostimulatingtoysandbooks,orpreventparentsspendingsufficienttime talking,readingorplayingwiththeirchildren.Alternatively,assessingtheimpactof thesesameparentalissuesontheeducationofadolescentsaged11–15yearsneeds tofocusondifferentthemes–forexample,schoolattendanceandinvolvementin otherlearningactivitiessuchassport,musicorhobbies.

Withineachdimensionandforeachagegroup,evidenceisusedtohighlight boththeadverseimpactonchildrenandthefactorswhichactasprotectors,suchas thestrategieschildrenusetocopewithstressfulfamilysituationsandthesupport andinfluenceofthewiderfamilyandcommunity.

Thebookisdividedintothreeparts,PartsI,IIandIII.

Part IincludesChapters1–3andexploresthefollowinggeneralissues:

Chapter 1:questionswhetherconcernisjustified,andexplorestheproblemsof definitionandprevalence.

Chapter 2:exploresthewaysinwhichmentalillness,learningdisability,problem druguse(includingalcohol)anddomesticviolenceaffectparentingcapacity. Chapter 3:identifieswhichchildrenaremostvulnerable.

Part IIincludesChapters4–6,withaspecificfocusonchildrenofdifferentages andstagesofdevelopment:

Chapter 4:discussestheimpactofparentalproblemsforchildrenunder5 years.

Chapter 5:focusesontheissuesforchildrenaged5to10years. Chapter 6:focusesonyoungpeopleaged11yearsandover.

Part IIIincludesChapters7and8whichdrawtogetherthefindingsand implicationforpolicyandpractice:

Chapter 7:discussestheconclusionsfromthestudy.

1

definition and prevalence

Tounderstandwhetherthepresentconcernsoverparentalmentalillness,learning disability,problemalcoholanddruguseordomesticviolencearejustified,this chapterexaminestheproblemswithterminologyandtheprevalenceoftheseissues. Generalpopulationstudiesprovideevidenceoftheirprevalenceandtherelevance ofgender,cultureandclass.Findingsfromchildprotectionresearchareusedto identifyassociationsbetweentheseparentalproblemsandchildren’shealthand development,includingtheextenttowhichtheymayposeariskofsignificant harmtothechild.

Problems with terminology

Understandingthedegreeoftheseparentalproblemsisdifficultbecausedifferent researchstudiesusedifferenttermsandtherearefewdefinitionsprovided. Forexample,intheDepartmentofHealth’s1995studiesonchildprotection (DepartmentofHealth1995a)itisunclearwhetherSharlandetal.’s(1996)parents whohave‘relationshipproblems’areasimilargrouptoThoburnetal.’s(1995) parentswhoarein‘maritalconflict’,orFarmerandOwen’s(1995)familieswhoare experiencing‘domesticviolence’.Difficultiesalsoarisebecause,forexample,different countriesusedifferentwaysofmeasuringdrugandalcoholuse.Forinstance,the ‘unitofalcohol’intheUnitedKingdomhaslittlemeaningintheUSwheredifferent measuresofalcoholareusedinpeerreviewedjournalsandresearch.Inaddition,the purityofdrugsusedindifferentcountriesmaydiffer.Forexample,agramofheroin inNewYorkmaybemoreorlesspurethanagramofheroininLondon.

Whenscrutinisingtheliteratureonmentalillness,learningdisability,problem alcoholanddruguse,anddomesticviolencetheauthorshavebeenguidedintheuse oftermsbythefollowingpolicyandpracticedocuments.

Mentalillness

ClinicalstudiesofadultsgenerallydefinementalillnesseitherbyusingtheEuropean system:TheICD10ClassificationofMentalIllnessandBehaviouralDisorders(World HealthOrganisation1992)ortheUSclassification:DiagnosticandStatistical ManualofMentalDisorders(AmericanPsychiatricAssociation2000).Unfortunately, thequalityofinformationfromcommunitybasedrecordsmayprecludesuch aprecisediagnosis.Inaddition,therecontinuestobeconsiderabledisputeover whether‘personalitydisorder’isapsychiatricillnessassuchormerelyadescription ofextremesofnormalvariation(seeKendell2002foradiscussionofthisissue). Moreover,because‘personalitydysfunctionhasbeenrepeatedlydescribedinanecdotal casereports,clinicalstudiesandsurveysoftheparentsofmaltreatedchildren’(Falkov 1997,p.42)itwasthoughtthattoomititinastudyoftheimpactonchildrenof parentalproblemswouldberemiss.Insomeways,therecentamendmentstothe MentalHealthAct2007simplifytheissueinclinicaltermswiththeuseofanew expression–‘mentaldisorder’–whichisdefinedas‘anydisorderordisabilityof themind’butexcludesbothalcoholanddrugdependenceand‘learningdisabilities unlesswithabnormallyaggressiveorseriouslyirresponsiblebehaviour’.

Learningdisability

TheDepartmentofHealth’sdefinitionoflearningdisabilityencompassespeople withabroadrangeofdisabilities.Learningdisabilityincludesthepresenceof:

エ!

asignificantlyreducedabilitytounderstandneworcomplexinformation,to learnnewskills(impairedintelligence);withエ!

areducedabilitytocopeindependently(impairedsocialfunctioning);エ!

whichstartedbeforeadulthood,withalastingeffectondevelopment.(HMGovernment2010a,p.279,paragraph9.56) Mencapalsoprovidesacleardescriptionoflearningdisability.

Alearningdisabilityiscausedbythewaythebraindevelops.Therearemany differenttypesandmostdevelopbeforeababyisborn,duringbirthorbecauseof aseriousillnessinearlychildhood.Alearningdisabilitycanbemild,moderate, severeorprofound,butallarelifelong.Manypeoplewithalearningdisability, however,liveindependentlives.

birth,braininjuryatbirth,braininfectionsorbraindamageafterbirth.Examples includeDown’ssyndrome,FragileXsyndromeandcerebralpalsy(RoyalCollegeof Psychiatrists2004a).

Problemdrinking

TheNationalInstituteforHealthandClinicalExcellence(2010)intheirpublic healthguidanceonalcoholusedisordersprovidesthefollowingdefinitions: Hazardous drinking Apatternofalcoholconsumptionthatincreasessomeone’s riskofharm.

Harmful drinking Apatternofalcoholconsumptionthatiscausingmentalor physicaldamage.

Higher-risk drinking Regularlyconsumingover50alcoholunitsperweek(adult men)orover35unitsperweek(adultwomen).

IntheUnitedKingdomoneunitisequivalenttohalfapintofordinarystrength lagerorbeeroroneshot(25ml)ofspirits,whileasmall(125ml)glassofwineis equalto1.5units.Theunitmeasurehaslostsomeofitsvalueandsimplicitybecause fewpubsorrestaurantsserve125mlglassesofwine(theyarenoweither175ml or250ml).Also,whentheunitwasdevisedwinewascalculatedashavingon average9%alcohol,whilemostwinesthesedaysare12–15%.Similarly,thealcohol contentofmanybeersandlagersisnowmorethanitwaswhentheunitsystem wasestablished.Previously,thealcoholcontentofbeerandlagerwasestimatedat 3.5–4.0%.Nowmostbeersarestronger,3.5–9.0%,withmanypopularbeersat5%. Thepub‘measure’ofspiritshas,insomepubs,beenreplacedbya35mlmeasure. Recently,thenumberofunitsofalcoholinabottleofwinehasbeenprintedonthe label.

TheGovernmentstrategyforpublichealth(Cm79852010)acknowledgesthe deleteriousimpactofheavydrinkingonhealthandthenegativeeffectonothers.

‘Drunkennessisassociatedwithalmosthalfofassaultandmorethanaquarterofdomestic violenceincidents’(p.20,paragraph1.31).

Problemdruguse

Researchintoproblemdruguseemploysabewilderingrangeoftermsinits descriptionsincludingdruguse,drugmisuse,drugdependence,addiction,drug abuseandproblemdruguse.Thesetermsarenotalwaysdefined,whichmakesit difficulttocomparethefindingsfromonestudywithanother.Forinstance,someone canbeaproblemdruguser(havingproblemsasaresultofdruguse)butnotsuffer fromaddiction(suggestingphysicalandpsychologicaldependence).

Byproblemdrugusewemeandrugusewithseriousnegativeconsequencesof aphysical,psychological,socialandinterpersonal,financialorlegalnaturefor usersandthosearoundthem.Suchdrugusewillusuallybeheavy,withfeatures ofdependence.

(AdvisoryCouncilontheMisuseofDrugs2003,p.7)

Domesticviolence

Whenconsideringdomesticviolence,the2009definitionusedbytheHomeOffice wasfoundtobehelpful.

Domesticviolenceis‘Anyincidentofthreateningbehaviour,violenceorabuse (psychological,physical,sexual,financialoremotional)betweenadultswhoareor havebeenintimatepartnersorfamilymembers,regardlessofgenderorsexuality.’ Thisincludesissuesofconcerntoblackandminorityethnic(BME)communities suchassocalled‘honourbasedviolence’,femalegenitalmutilation(FGM)and forcedmarriage.

(HomeOffice2009b)

Thisdefinitionofdomesticviolencedoesnotconfineitselftophysicalorsexual assaultsbutincludesarangeofabusivebehaviourswhicharenotinthemselves inherentlyviolent.Asaconsequence,someauthorsprefertousetheterm‘domestic abuse’.Itshouldalsobenotedthatdomesticviolencerecognisesfewsocial boundaries.Forexample,researchonfemalevictimsofdomesticviolencereports that‘violenceagainstwomenisthemostdemocraticofallcrimes,itcrossesallreligious, classandracebarriers’(Women’sAid1995).

Childabuseandneglect

Childabuseandneglectareformsofchildmaltreatmentandresultfromanyone (butmorecommonlyaparentorcarer)inflictingharmorfailingtoacttoprevent harm.Statutoryguidanceprovidesthefollowingdescriptionsofabuseandneglect.

Physicalabusemayinvolvehitting,shaking,throwing,poisoning,burningor scalding,drowning,suffocating,orotherwisecausingphysicalharmtoachild. Physicalharmmayalsobecausedwhenaparentorcarerfabricatesthesymptoms of,ordeliberatelyinduces,illnessinachild.

overprotectionandlimitationofexplorationandlearning,orpreventingthechild participatinginnormalsocialinteraction.Itmayinvolveseeingorhearingtheill treatmentofanother.Itmayinvolveseriousbullying(includingcyberbullying), causingchildrenfrequentlytofeelfrightenedorindanger,ortheexploitationor corruptionofchildren.Somelevelofemotionalabuseisinvolvedinalltypesof maltreatmentofachild,thoughitmayoccuralone.

Sexualabuseinvolvesforcingorenticingachildoryoungpersontotakepart insexualactivities,notnecessarilyinvolvingahighlevelofviolence,whetheror notthechildisawareofwhatishappening.Theactivitiesmayinvolvephysical contact,includingassaultbypenetration(forexample,rapeororalsex)ornon penetrativeactssuchasmasturbation,kissing,rubbingandtouchingoutsideof clothing.Theymayalsoincludenoncontactactivities,suchasinvolvingchildren inlookingat,orintheproductionof,sexualimages,watchingsexualactivities, encouragingchildrentobehaveinsexuallyinappropriateways,orgroominga childinpreparationforabuse(includingviatheinternet).Sexualabuseisnot solelyperpetratedbyadultmales.Womencanalsocommitactsofsexualabuse,as canotherchildren.

Neglectisthepersistentfailuretomeetachild’sbasicphysicaland/orpsychological needs,likelytoresultintheseriousimpairmentofthechild’shealthordevelopment. Neglectmayoccurduringpregnancyasaresultofmaternalsubstanceabuse.Once achildisborn,neglectmayinvolveaparentorcarerfailingto:

エ!

Provideadequatefood,clothingandshelter(includingexclusionfromhome orabandonment);

エ!

Protectachildfromphysicalandemotionalharmordanger;

エ!

Ensureadequatesupervision(includingtheuseofinadequatecaregivers); or

エ!

Ensureaccesstoappropriatemedicalcareortreatment.

エ!

Itmayalsoincludeneglectof,orunresponsivenessto,achild’sbasicemotional needs.

(HMGovernment2010a,p.3839,paragraphs1.331.36)

Prevalence

relationshipbetweenintelligence–untilitfallsbelowacertainlevel,usuallytaken tobeanIQof60orless–andparenting(BoothandBooth2004;Tymchuck1992). Itistheextremityorcombinationofthesesituations,particularlytheassociation withviolence,whichmayimpairparents’capacitytomeettheirchildren’sneeds and,insomesituations,resultinchildabuseandneglect.

Unfortunately,theabilitytoaccuratelygaugetheextentofparentalmentalillness, learningdisability,problemalcoholordruguse,anddomesticviolenceishampered notonlybyproblemsofterminologybutalsobecauseprevalencedependsupon thepopulationgroupbeingstudied.Forexample,communitybasedsamplessuch asthehouseholdsurveycarriedoutbytheOfficeforNationalStatisticswillbe morerepresentativethanresearchwhichfocusesonspecificgroups,suchashospital patients,womenandchildreninrefuges,orthosewhoattendclinicsorcourts. Moreover,theseverityoftheconditionunderstudyislikelytobemuchgreaterin specificsamplegroupsasisthecoexistenceofavarietyofadditionalproblems.But regardlessofthetypeofsamplegroupunderconsideration,anygeneralisationsto samplesbeyondthatbeingstudiedshouldbemadewithconsiderablecaution.

Thefollowingsectionsexplore,inturn,theexistingevidenceontheprevalence of:

エ!

parentalmentalillnessエ!

learningdisabilityエ!

problemdrinkinganddruguseエ!

domesticviolence.Twosourcesareexaminedforeachcategory:

エ!

generalpopulationstudiesエ!

childprotectionresearch.Prevalence of parental mental illness: general

population studies

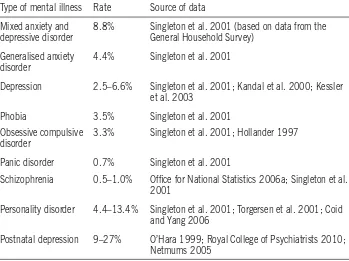

Type of mental illness Rate Source of data Mixed anxiety and

depressive disorder

8.8% Singleton et al. 2001 (based on data from the General Household Survey)

Generalised anxiety disorder

4.4% Singleton et al. 2001

Depression 2.5–6.6% Singleton et al. 2001; Kandal et al. 2000; Kessler et al. 2003

Phobia 3.5% Singleton et al. 2001 Obsessive compulsive

disorder

3.3% Singleton et al. 2001; Hollander 1997

Panic disorder 0.7% Singleton et al. 2001

Schizophrenia 0.5–1.0% Office for National Statistics 2006a; Singleton et al. 2001

Personality disorder 4.4–13.4% Singleton et al. 2001; Torgersen et al. 2001; Coid and Yang 2006

Postnatal depression 9–27% O’Hara 1999; Royal College of Psychiatrists 2010; Netmums 2005

Itisencouragingtonotethattheproportionofpeoplereceivingtreatmentfor mentalhealthdifficultieshasincreasedfrom14%in1993to24%in2000.In themainthiswastheresultofadoublingintheproportionofthosereceiving medication,whereasaccesstopsychologicaltreatmenthasremainedconstant(Office forNationalStatistics2005).

Thepictureiscomplicatedbecausementalillnessfrequentlyexistsalongsideother disorders.Forexample,USresearchindicatesthathalfofthosewithadiagnosis ofschizophrenia(Swoffordetal.2000)andnearlyathirdofthosewithamood disorderalsomisusedorweredependentuponalcoholordrugs(Regieretal.1990). TheworkofRosenthalandWestreich(1999)intheUSalsosuggeststhathalfof individualswhoexperiencealcoholordrugproblemsormentalhealthdisorders willhavetwoormoreofthesedisordersovertheirlifetime.WorkintheUnited Kingdomwhichfocusedonthoseattendingmentalhealthservicesfound44%of patientsselfreportedproblemuseofdrugsand/orwereassessedtohaveusedalcohol athazardousorharmfullevelsinthepreviousyear(Weaveretal.2002).

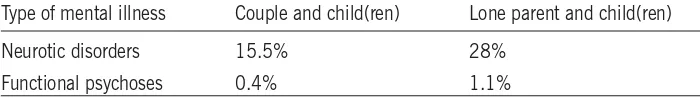

thedatabythetypeoffamilyunit,showedpsychiatricmorbiditytobeassociated withfamilycharacteristics.Coupleslivingwithchildrenhaveagreatermorbidity forbothneuroticdisorder(155perthousand)andfunctionalpsychoses(4per thousand)thancoupleswithoutchildren(134perthousandforneuroticdisorder andtwoperthousandforfunctionalpsychoses).Thedataalsoshowahigherrateof mentalillnessforloneparentsthanforadultslivingasacouplewithchildren(see Table1.2).Thesefindingssuggestthatchildrenmaybemorevulnerabletoharm andneglectwhenlivingwithaloneparentwhosuffersfrommentalillness,because whentheparentisexperiencingthedisorderthereislikelytobenoothercaring adultlivinginthehometotakeontheparentingrole.

Table 1.2: Prevalenceofmentalillnessamongparentsinthegeneralpopulation

Type of mental illness Couple and child(ren) Lone parent and child(ren) Neurotic disorders 15.5% 28%

Functional psychoses 0.4% 1.1%

Parentalmentalillness:issuesofgender,

cultureandclass

Researchonfathersormalecarerswithmentalhealthproblemsissparse.What isclearisthatmenwholiveeitherasacouplewithchildrenorinaloneparent situationhavealowerrateofneuroticdisorderandfunctionalpsychosesthando womeninsimilarsituations(Singletonetal.2001;CoidandYang2006).

Incontrast,thereisaconsiderablebodyofworkwhichrecordstherateofmental illnessinmothers.Somewhatsurprisingisthattheprevalenceofmaternalmental illnessappearstovaryfromcountrytocountry.Forexample,anAmericanstudy suggestsasmanyas25–39%ofwomensufferdepressionfollowingchildbirth (CentreforDiseaseControlandPrevention2004),whereasBritishstudieshave traditionallyplacedthefigureataround10%(O’HaraandSwain1996).However, amorerecentonlinesurveysuggestsdepressionfollowingchildbirthhasincreased significantlyoverthepast50yearsinBritain,upfrom8%inthe1950sto27% today(Netmums2005).Onemightquestionwhetherthevarianceinreported ratesofmentalillnessisduetorealdifferencesinprevalence,inhowmentalillness manifestsitself,orinthemethodsofassessmentandrecording.Forexample,the USstudy(CentreforDiseaseControlandPrevention2004)of453,186women recordeddepressionintermsofitsseverityandfound7.1%ofmothersreported experiencingseveredepression,andjustmorethanhalfreportedexperiencinglow tomoderatedepressionfollowingchildbirth.

qualificationsandtocomefromsocialclassV(unskilled,manualoccupations)and beeconomicallyinactive.Adultswithmentalhealthproblemshavethehighest unemploymentratesforanyofthemaingroupsofdisabledpeople;only21%are employed(OfficeforNationalStatistics2006b).Theimpactofclassandpovertyare exacerbatedwhenadultsareparentscaringforchildren.‘...amongthosewithchildren athome,workingclasswomenwerefourtimesmorelikelytosufferfromadefinite psychiatricdisorder’thancomparablemiddleclasswomen(BrownandHarris1978, p.278).

Vulnerabilitytomentaldisordersmaybetheresultofadverselifeeventssuchas poverty,poorenvironment,sexismorracismandotherformsofsocialdisadvantage (CentreforDiseaseControlandPrevention2004;GhateandHazel2002;Propper etal.2004).Forexample,researchbasedin15electoralwardsinLondonfoundthe incidenceofschizophreniainnonwhiteminoritieswasrelatedtotheproportion oftheethnicminoritylivinginthearea;thesmallertheminoritygroupthegreater theincidenceofschizophrenia(Boydelletal.2001).Ofsignificanceareindividual experiences,particularlythoseinvolvinglongtermthreat(BrownandHarris1978; Sheppard1993).

Thepictureisfurthercloudedbecausementalillnessisperceiveddifferently bydifferentculturalgroups(NSPCC1997a;Anglinetal2006).Forexample, theliteratureseemstosuggestthatinsomesouthAsianculturesmentalillnessis expressedintermsofphysiologicalailments.Asaresult,symptomsmaybereported asproblemsrequiringmedicalratherthanpsychiatricservices.Likewise,insome culturesoutsidetheWesternworldschizophreniaisinterpretedasapossessionof thesuffererbymalevolentspirits,andtheservicesofpriestsratherthandoctorsare sought(LittlewoodandLipsedge1997).

Thiscumulativebodyofevidence,althoughillustratingsomeofthedifficulties inassessingprevalence,suggeststhataconsiderablenumberofchildrenarelivingin familieswhereatleastoneparentissufferingfromamentalillness.

Prevalenceofparentalmentalillness:

childprotectionstudies

Themajorityofparentswhoexperiencementalillnessdonotneglectorharmtheir childrensimplyasaconsequenceofthedisorder(Tunnard2004).Childrenbecome morevulnerabletoabuseandneglectwhenparentalmentalillnesscoexistswith otherproblemssuchassubstancemisuse,domesticviolenceorchildhoodabuse (Cleaveretal.2007).

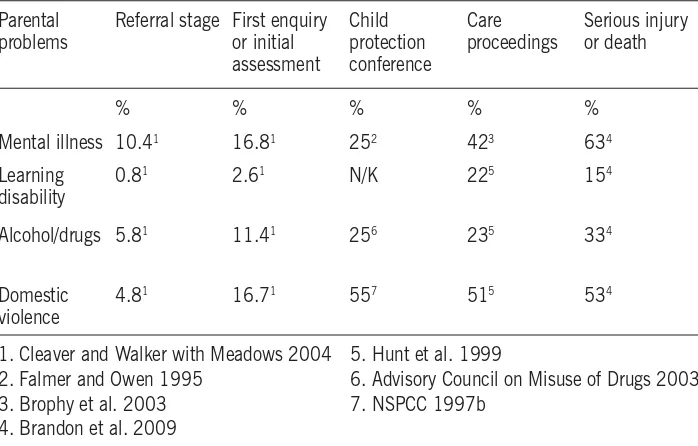

WalkerwithMeadows’(2004)studyof2,248referralstochildren’ssocialcarefound, onreanalysingtheirdata,thatparentalmentalillnesswasrecordedin10.4%of referrals,afindingsimilartothe13%identifiedbyGibbonsetal.(1995).However, prevalenceincreaseswithgreaterknowledgeofthefamilycircumstances.Following aninitialassessment,socialworkersrecordedparentalmentalillnessin16.9%of cases(CleaverandWalkerwithMeadows2004).Whencasescomeundergreater scrutinyandachildprotectionconferenceisheld,prevalenceincreasesonceagain. Parentalmentalillnesswasidentifiedinaquarterofcasescomingtoconference (FarmerandOwen1995).Thereisafurtherriseinprevalenceforchildreninvolved incareproceedings.Parentalmentalillnesshadbeennotedinsome43%ofcases wherechildrenarethesubjectofcareproceedings(42%inHuntetal.1999;and 43%inBrophyetal.2003).

Earlyresearchonchildmurderrecordedparticularlyhighratesofmaternalmental illness.Resnich’s(1969)reviewof131casesofparentalchildmurderidentified71% ofmothersasbeingdepressedandGibson’s(1975)studyofmaternalfilicidenoted 90%ofthemothershadapsychiatricdisorder.Morerecentresearchintoextreme casesofchildabusetempersthesefindings,althoughthereremainsconsiderable variation.Falkov’s(1996)studyoffatalchildabusefound32%ofparentshada psychiatricdisorder,afindingsimilartotherate(28%)identifiedinfamiliessubject toseriouscasereviewsduring2007–8(Ofstedetal.2008).However,thisislikelyto beanunderestimate.Theanalysisofanintensivesampleof40seriouscasereviews foundalmosttwothirds(63%)ofchildrenlivedinahouseholdwithaparentor carerwithcurrentorpastmentalillness(Brandonetal.2009and2010),afigure ratherhigherthanthe43%foundinRederandDuncan’s1999studyoffatalchild abuse.

Thefocusonmothers,commoninmuchofthechildprotectionresearch,might suggestthattheyaremorepronetokillingtheirchildren.However,filicideisnot theprerogativeofmothers.Exceptforneonates,fathersandfatherfiguresaremore likelytomurderachildintheircarethanaremothers(MarksandKumar1996; Stroud1997;Cavanaghetal.2007).

Fatheradmittedshakingthebaby...Bothparentshaveahistoryofmentalillness. Littleknownaboutfamily,buttheyhavehadfrequenthousemovesandchanges ofname.

(Brandonetal.2008,p.46)

Parentalmentalillnessandtypeofchildabuse

parentalmentalillnesswasrecordedin31%ofcases(GlaserandPrior1997). Researchonchildsexualabusealsosuggestsagreaterassociationwithparental mentalillness.Sharlandandcolleagues’(1996)studyofchildsexualabusefound 71%offamilies,wherethereweresuspicionsofabuse,wereina‘poorpsychological state’usingtheGeneralHealthQuestionnaire(GoldbergandWilliams1988)and therewasafurtherincreasewhensuspicionswereconfirmed.Thesefindingsarein linewithMoncketal.’s(1995)studyoffamiliesattendingaspecialisedtreatmentand assessmentdayclinicforchildsexualabuse.Theyfound86%ofmothers(assessed usingtheGeneralHealthQuestionnaire)showedsymptomsofdepressionoranxiety and,foraconsiderableproportion,thesymptomshadbeenoflongduration.

Caution,however,mustbeexercisedinrelationtothesefindingsbecausestudies ofphysicalabuseandneglecthavetendednottousestandardisedmeasuresofmental healthanditisnotpossibletocomparelikewithlike.

Prevalence of parental learning disability:

general population studies

Theprevalenceoflearningdisabilityamongthegeneralpopulationisdifficultto establishbecausenoinformationiskeptnationally.EmersonandHatton(2008), usingdatafrom24localauthoritiesestimatedthattherewere985,000peoplein Englandwithalearningdisability,equivalenttoanoverallprevalencerateof2%of theadultpopulation.

However,McGawandNewman(2005)raiseanoteofcaution,pointingout howdifferencesinclassificationresultinconfusionandinconsistency.Traditionally, scoresonstandardisedintelligencetestshavebeenusedtodefinelearningdisability; approximatelytwothirdsofpeople(69%)fallwithinthenormalrangeof85to115 (averageIQbeing100).Individualswhoseresultsaretwostandarddeviationsbelow themean,i.e.anIQof70orbelow,areclassifiedas‘learningdisabled’(Dowdney andSkuse1993).Onedifficultyinestablishingtheprevalenceoflearningdisability relatestohowthosewithborderlineIQs(70to85)areclassified.Inaddition, individualsmayexhibitdifferentabilitylevelsacrossthecomponentsofIQand othertestsused.‘...inrealitythereisnocleardemarcationbetweenparentswhohave learningdisabilitiesandthosewhodonot’(McGawandNewman2005,p.8).

parentswithlearningdisabilitiesincontactwithservices’(DepartmentofHealthand DepartmentforEducationandSkills2007,p.36).

Peoplewithalearningdisabilityhavegreaterphysicalandmentalhealthneeds andaremorelikelytohaveexperiencedchildhoodabuseorneglectthantherestof thepopulation(McGawetal.2007).Forexample,intheUnitedKingdomresearch indicates25–40%ofadultswithalearningdisabilitywillexperienceamentalhealth problematsomepointintheirlives(MIND2007).Inparticular,ratesofschizophrenia arethreetimeshigherthaninthegeneralpopulation,althoughtherearefewdataon theprevalenceofothertypesofmentalillness(Hassiotisetal.2000).

Parentallearningdisability:issuesofgender,culture

andclass

Mostreportsandstudiesinvolvingpeoplewithlearningdisabilitiesdonot differentiatebetweenmenandwomen.AsMcCarthy(1999)explains‘Itisasif havingalearningdisabilityoverridesallotheridentitiesanditis,somewhatbizarrely,as ifitispoliticallyincorrecttodrawattentiontogenderdifferences.’Literaturethatdoes differentiatebetweenmenandwomenwithlearningdisabilitiestendstofocuson sexualityandsexualabuse.Studiesfocusingonmenwithalearningdisabilityare almostexclusivelyabouttheirsexualbehaviour,andthosewhichfocusonwomen highlighttheirsexualvulnerability(McCarthy1999).

Incontrast,muchresearchhasdrawnattentiontothevulnerabilityoffamilies whereoneormoreparenthasalearningdisability.Parentswithlearningdisabilities havebeenfoundtobeamongstthemostsociallyandeconomicallydisadvantaged groups.Thefinancialdifficultiesfacedbythesefamiliesareillustratedinthefigures drawntogetherbyMencap.Thedatashowthatlessthanoneinfivepeoplewith learningdisabilitiesareinwork(comparedwithoneintwodisabledpeoplegenerally) andthatthosewhoareworkingaremostlyonlyworkingparttimeandarelow paid.Justoneinthreepeoplewithlearningdisabilitiestakepartinsomeformof educationortraining(Mencap2008).

Prevalenceofparentallearningdisability:child

protectionstudies

disability.Parentallearningdisabilityisfrequentlyidentifiedasoneofthemany cocurrentproblemsthatimpactonparents’capacitytosafeguardandpromotethe welfareoftheirchildren(CleaverandFreeman1995;CleaverandNicholson2007). Finally,inanintensivestudyof40seriouscasereviews15%ofchildrenwereliving withaparentwithalearningdisability(Brandonetal.2009).

Areviewofresearchsuggeststhatbetween40%and60%ofparentswithlearning disabilitieshavetheirchildrentakenintocareasaresultofcourtproceedings (McConnellandLlewellyn2002).Amorerecentsurveyof2,893peoplewith learningdisabilitiesinEnglandfoundofthosewhowereparents,justunderhalf (48%)werenotlookingaftertheirchildren(Emersonetal.2005).However, thisfigureincludedchildrenwhohadlefthomebecausetheyhadgrownupand, therefore,itmustnotbeassumedthat48%ofparentswithalearningdisabilityhad hadtheirchildrentakenintocare.Thesefigurescontrastgreatlywiththefindings fromanindepthfollowupstudyof64casesreferredtochildren’ssocialcarewhere oneorbothparentshadalearningdisability(CleaverandNicholson2007).In thisstudymostchildrencontinuedtolivewiththeirparentsfollowingareferralto children’ssocialcare.Threeyearsaftertheinitialreferralonly12children(18.8%) hadbeenremovedfromtheirparents’care,includingtwochildrenwhohadbeen placedforadoption.

Parentallearningdisabilityandtypeofchildabuse

Learningdisabilityisnotcorrelatedwithdeliberateabuseofchildren‘...IQbyitself, isnotapredictoreitheroftheoccurrenceorofthenonoccurrenceofpurposefulchild abuse...’(Tymchuck1992,p.169).Infact,thereisconsiderableevidencetoshow thatanaccumulationofthestressorsrelevanttoallparentsaremorepredictive ofpoorparentingthanIQscores.Theseinclude,forexample,poverty,inadequate housing,maritaldisharmonyandviolence,poormentalhealth,childhoodabuse, substancemisuseandalackofsocialsupports(Craft1993;BoothandBooth 1996;CleaverandNicholson2007).Inaddition,parentsmayhavethechallenge ofcaringforadisabledchild.Childrenborntoparentswithalearningdisability areatincreasedriskofinheritedlearningdisabilitiesandpsychologicalandphysical disorders(McGawandNewman2005).