Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 21:53

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Interpreting Standardized Assessment Test Scores

and Setting Performance Goals in the Context of

Student Characteristics: The Case of the Major

Field Test in Business

Agnieszka Bielinska-Kwapisz , F. William Brown & Richard Semenik

To cite this article: Agnieszka Bielinska-Kwapisz , F. William Brown & Richard Semenik (2012) Interpreting Standardized Assessment Test Scores and Setting Performance Goals in the Context of Student Characteristics: The Case of the Major Field Test in Business, Journal of Education for Business, 87:1, 7-13, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.542504

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2010.542504

Published online: 21 Nov 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 169

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.542504

Interpreting Standardized Assessment Test Scores

and Setting Performance Goals in the Context of

Student Characteristics: The Case of the Major Field

Test in Business

Agnieszka Bielinska-Kwapisz, F. William Brown, and Richard Semenik

Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana, USAThe Major Field Test in Business (MFT-B), a standardized assessment test of business knowl-edge among undergraduate business seniors, is widely used to measure student achievement. The Educational Testing Service, publisher of the assessment, provides data that allow institu-tions to compare their own MFT-B performance to national norms, but that procedure fails to take the characteristics of institutional student cohorts into account. Using empirical methods, the authors describe and test a procedure to set a priori goals that take dispositional factors, most notably ACT scores, into account. This procedure enables interpretation of the MFT-B in relation to expectations.

Keywords:assessment of learning, higher education, Major Field Test assessment goals, mean absolute error, root mean squared error, standardized tests

For a variety of reasons there has been considerable interest and attention directed to the assessment of learning in higher education. The use of standardized assessment instruments has become a significant part of this process. The Educa-tional Testing Service (ETS) publishes the Major Field Test in Business (MFT-B), an assessment tool intended for use in schools offering undergraduate business programs, and re-ported that it was administered to 132,647 individuals at 618 different institutions between 2006 and 2009 (Educational Testing Service [ETS], 2009). Martell (2007) reported that, in 2006, 46% of business schools used the MFT-B in their assessment of students’ learning. Often, the primary motiva-tion in administering the test is to offer accrediting bodies, such as the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB), evidence that a program is fulfilling or making progress toward its stated mission.

The ETS has described the MFT-B as being constructed according to specifications developed and reviewed by com-mittees of subject matter experts so as to go beyond the mere measurement of factual knowledge and go on to evaluate

Correspondence should be addressed to F. William Brown, Montana State University, College of Business, P. O. Box 173040, Bozeman, MT 59717-3040, USA. E-mail: billbrown@montana.edu

students’ ability to analyze and solve problems, understand relationships, and interpret material from their major field of study (ETS, 2009). The test contains 120 multiple-choice items covering the common body of knowledge for under-graduate business education: accounting (15%), management (15%), economics (13%), finance (13%), marketing (13%), qualitative analysis (11%), information systems (10%), legal and social environment (10%), and international considera-tions of modern business operaconsidera-tions (12% overlap with the rest). The scores range from 120 to 200 and the ETS reported the mean score to be 153.1 with a standard deviation of 14.1 for 2009 (ETS, 2009).

Although the ETS does provide data that allow institutions to compare their own MFT-B performance to national norms, the data provided do not take the characteristics of institutions and student cohorts into account, greatly limiting the utility and interpretative meaningfulness of local comparisons.

Because of the potential value and extensive administra-tion of the MFT-B, comparisons of student performance have attracted at least some attention from researchers. Utilizing ACT scores as a proxy for cognitive intelligence (Koenig, Frey, & Detterman, 2008) researchers have examined MFT-B performance in a variety of academic settings and con-sistently report strong correlations between ACT scores and MFT-B scores. Zeis, Waronska, and Fuller (2009); Bycio and

8 A. BIELINSKA-KWAPISZ ET AL.

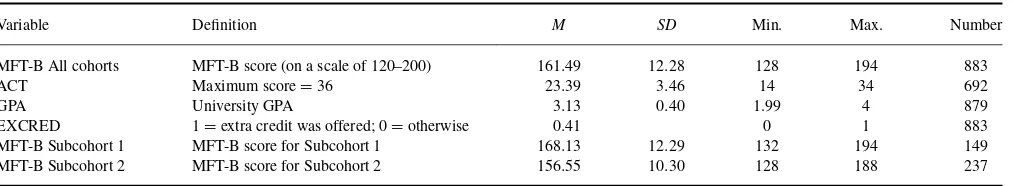

TABLE 1 Descriptive Statistics

Variable Definition M SD Min. Max. Number MFT-B All cohorts MFT-B score (on a scale of 120–200) 161.49 12.28 128 194 883 ACT Maximum score=36 23.39 3.46 14 34 692 GPA University GPA 3.13 0.40 1.99 4 879 EXCRED 1=extra credit was offered; 0=otherwise 0.41 0 1 883 MFT-B Subcohort 1 MFT-B score for Subcohort 1 168.13 12.29 132 194 149 MFT-B Subcohort 2 MFT-B score for Subcohort 2 156.55 10.30 128 188 237

MFT-B=Major Field Test in Business; GPA=grade point average.

Allen (2007); Black and Duhon (2003); Bean and Bernardi (2002); Stoloff and Feeney (2002); Mirchandani, Lynch, and Hamilton (2001); and Allen and Bycio (1997) all reported a similar relationship between ACT and MFT-B scores. Tak-ing a slightly different perspective, Rook and Tanyel (2009) found that business core grade point average (GPA) was a slightly better predictor of test improvement than upper level business GPA. Following these two lines, Bielinska-Kwapisz, Brown, and Semenik (2010) demonstrated a sig-nificant predictive relationship between ACT scores, GPAs, and MFT-B scores; analyzed the differences between majors; and concluded that meaningful interpretation or comparison of MFT-B scores must take student characteristics into con-sideration to more fully understand the meaning of perfor-mance on the MFT-B. Extending that line of inquiry, in this study we utilized a large stock of MFT-B scores collected over 5 years from graduating seniors at the business school of a Carnegie I Research Institution. The general objective was to further examine the explanatory and predictive value of ACT scores, GPAs, and other individual characteristics on MFT-B performance; however, more specifically the par-ticular contribution of this article is the description of an empirical technique as to how goals and expectations might be established for local cohorts (e.g., graduating classes and majors) and then make objectively supported judgments as to whether MFT-B performance was above or below the unique expectations for those cohorts at that institution.

METHOD

The root mean square error (RMSE) and the mean absolute error (MAE) have been utilized to compare the predictions from different explanatory models (Greene, 2003). Ismail, Yahya, and Shabri (2009) used this methodology to forecast gold prices and Bin (2004) forecasted housing sale prices. Data for the present study were obtained from 692 students taking the MFT-B assessment between 2005 and 2009 at an AACSB-accredited business school. The main variable of interest was a student’s MFT-B score. But, in addition, for each of the 692 students in this study, additional data re-garding university GPA measured at the time of graduation,

the major area of study (accounting, finance, management, marketing—randomly recoded as Subcohorts 1 to 4), the ACT scores, and whether the student received extra credit for performance achievement on the MFT-B (e.g., 5 points for a 50th-percentile score, 7.5 points for 75th-percentile) were also considered. Many business programs administering the MFT-B do offer some form of credit for taking the exam (Bycio & Allen, 1997). Extra credit was offered to partici-pants in this study from the spring of 2008 to the spring 2009. Table 1 displays definitions and basic descriptive statistics for all of these elements, and Table 2 reports bivariate correla-tions between variables from Table 1.

For all subcohorts together (k=all subcohorts) and two subcohorts separately (k=Subcohort 1 or 2), parameters of the following equations were estimated including the ACT and GPA scores (Equation 1), only ACT score (Equation 2), and only GPA score (Equation 3):

MFT-Bik =β0k+β1kACTik+β2kGPAik+εik, (1) MFT-Bik =β0k+β1kACTik+εik, (2) MFT-Bik =β0k+β1kGPAik+εik, (3)

where MFT-Bik, ACTik, and GPAik are the MFT-B, ACT, and GPA of studentiin subcohortk;β-sare parameters to be estimated; and εik is the error term. Depending on the goodness of fit, Equation 1, 2, or 3 was chosen for the com-plete cohort and two subcohorts separately. To these three basic specifications the binary variable EXCRED was added if it improved the overall fit. The EXCRED variable takes a value of 1 if the student received extra credit for performance

TABLE 2

MFT-B=Major Field Test in Business; GPA=grade point average.

TABLE 3

MFT-B Scores Prediction Comparison–Complete Cohort (n=692)

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Prediction equation (tratios in

parentheses)

96.5(30.8)+1.67(14.2)ACT+ +7.93(7.6)GPA+1.97(2.7)EXCRED

(Adj.R2=.41)

111(43.5)+2.1(19.7)ACT+ +

2.09(2.8)EXCRED (Adj.R2=.36)

115.6(40.1)+14.49(15.9)GPA+ +

1.44(1.9)EXCRED (Adj.R2=.23)

RMSE 1.233 1.216 2.002

MAE 1.097 1.127 1.590

RMSE=root mean square error; MAE=mean absolute error.

achievement on the MFT-B and 0 otherwise. For example, Equation 1 was then in the following form:

MFT-Bik=β0k+β1kACTik+β2kGPAik

+β3kEXCREDik+εik. (4)

The least square method was used to obtain the estimated linear regression equation.

The objective was to predict the value of y0 (MFT-B0) associated with a regressor vectorx0, wherexconsisted of all or some of the variables: ACT, GPA, and EXCRED. Then,

ˆ

y0=x0′bis the minimum variance linear unbiased estimator of E[y0|x0] wherey0=x0′β+ε0. The number of periods forecasted is denotedn0. The RMSE and MAE were defined in the following way (Greene, 2003):

RMSE= Both statistics are measured in the same unit of measure as the dependent variable (MFT-B scores). They can range from zero (perfect fit) to infinity and Singh, Knapp, and Demissie (2004) showed that both statistics may be considered low if the values are less than half the standard deviation of the measured data. Because the errors are squared, the RMSE gives high weight to large errors and is very useful if large errors are not desirable. The RMSE and MAE are close to each other if errors are in the same magnitude and the greater the difference between RMSE and the MAE, the greater the variance in the individual errors. Based on these statistics,

the best predictive model was identified for all subcohorts and each subcohort separately. This predictive equation can be used to assess the performance of a given subcohort.

RESULTS

Prediction Equation

Complete cohort. With respect to the goal of better un-derstanding influences on MFT-B overall performance, the ACT, GPA, and EXCRED variables were considered for the complete cohort. Significant relationships between the in-dependent and in-dependent variables and the coefficients of determination indicated that the fit was good (explaining ap-proximately 40% of the variation in MFT-B scores), therefore the estimated regression equation was considered appropriate for prediction.

The results of estimation of Equations 1–3 are presented in Table 3 (first row). The model with an extra credit binary variable fit the data best. Therefore, the EXCRED variable was included in all specifications. Table 3 provides the com-parison of MFT-B score predictions for the three models. The RMSE was 1.233 for the first model (with ACT and GPA), 1.216 for the second model (with ACT only), and 2.002 for the third model (with GPA only). Based on the RMSE, the second model that took into account only ACT scores out-performed all the other models in the prediction comparison. However, the MAE was the lowest for the first model. There-fore, if large errors are undesirable, the use of the following equation (Model 2) could set the standard for future cohorts

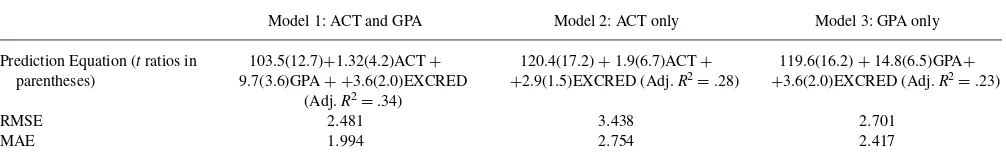

TABLE 4

Major Field Test in Business (MFT-B) Score Predictions for the Three Models for Subcohort 1 (n=119)

Model 1: ACT and GPA Model 2: ACT only Model 3: GPA only Prediction Equation (tratios in

parentheses)

RMSE=root mean square error; MAE=mean absolute error.

10 A. BIELINSKA-KWAPISZ ET AL.

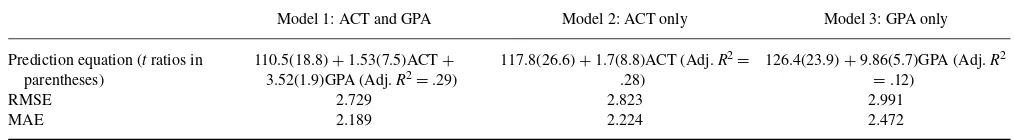

TABLE 5

MFT-B Scores Prediction Comparison–Subcohort 2 (n=193)

Model 1: ACT and GPA Model 2: ACT only Model 3: GPA only Prediction equation (tratios in

parentheses)

110.5(18.8)+1.53(7.5)ACT+

3.52(1.9)GPA (Adj.R2=.29)

117.8(26.6)+1.7(8.8)ACT (Adj.R2= .28)

126.4(23.9)+9.86(5.7)GPA (Adj.R2

=.12)

RMSE 2.729 2.823 2.991

MAE 2.189 2.224 2.472

RMSE=root mean square error; MAE=mean absolute error.

taking the MFT-B (if the extra credit was still offered):

BenchmarkMFT−B=111+2.1ACT

+2.09(EXCRED=1), (7)

whereMFT−B, andACT are the average MFT-B and ACT scores for this cohort. Based on both error measures, the average difference between the forecasted MFT-B and the observed MFT-B was about one point. This is a small error because it was much less than half the standard deviation of the MFT-B,which was 6.14 (following Singh et al., 2004). Therefore, it is possible to compare this point prediction to an actual MFT-B average to conclude if a given cohort of students has over- or underperformed on the MFT-B test in a given semester.

A similar analysis can be done for the subcohorts, in this instance a proxy for majors. In the study sample there were significant differences between represented subcohorts, and therefore different MFT-B scores should be expected. The two most extreme in terms of the MFT-B scores (Subcohorts 1 and 2) were chosen and analyzed here for comparison.

Subcohort 1. Table 4 shows the results of estima-tion of Equaestima-tions 1–3 and the comparison of MFT-B score predictions for the three models for Subcohort 1. As ex-pected, both error measures were slightly higher than they were for a complete cohort because we had fewer observa-tions. The errors ranged from 2 to 3.5, which suggests that the average difference between the forecasted MFT-B and the observed MFT-B was still small (it was much less than half the standard deviation of the MFT-B for Subcohort 1, which was 6.1). The RMSE and MAE were the smallest for Model 1. Therefore, the following equation (Model 1) could set the standard for future cohorts taking the MFT-B (if the extra credit were still offered):

BenchmarkMFT−B=103.5+9.7GPA +1.32ACT

+3.6(EXCRED=1), (8)

whereMFT−B,ACT, andGPA are the average MFT-B, ACT and GPA scores for this Subcohort.

Subcohort 2. For Subcohort 2, the best fit had a model without the EXCRED variable. Table 5 shows the results of

estimation of Equations 1–3 and the comparison of MFT-B score predictions for the three models for Subcohort 2.

The first model, which took into account GPA and ACT scores, outperformed all the other models in the prediction comparison. Therefore, for Subcohort 2, the following equa-tion was utilized to set the standard for future cohorts taking the MFT-B:

BenchmarkMFT−B=110.5+1.53∗ACT

+3.52∗GPA. (9)

whereMFT−B,ACT, andGPA are the average MFT-B, ACT and GPA scores for this subcohort.

Application

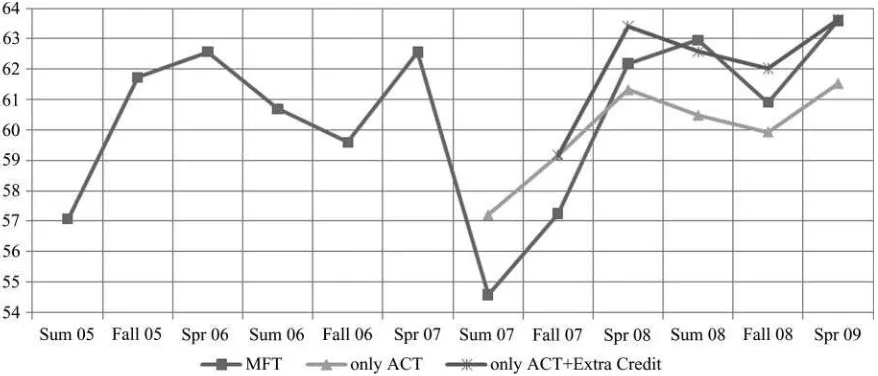

To demonstrate how this prediction equation could be used to assess the performance of cohorts on the MFT-B, the sam-ple was divided into two parts. The first segment was from summer 2005 to the spring 2007 semester, referred to as the training data set. The remainder of the study sample (from summer 2007 to spring 2009) was referred to as the valida-tion data set. The goal was to see if the more recent scores over- or underperformed on MFT-B assessment based on the history of the scores. Because incentivizing extra credit was not offered to members of the training data set (summer 2005 to spring 2007), the EXCRED variable could not be used; however, for subcohorts with a significant extra-credit variable (all cohorts and Subcohort 1), we offset the impact by using a coefficient from the previous analyses (Tables 3 and 4).

As can be seen in Table 6, the best fit for the training data set for all cohorts was the regression with ACT only.

TABLE 6

Regression Coefficients Based on the Training Data Set (Summer 2005 to Spring 2007)

All cohorts Subcohort 1 Subcohort 2 Constant (tratio in parentheses) 112.84 (32.2) 103.65 (8.9) 108.34 (14.0) ACT (tratio in parentheses) 2.06 (14.04) 1.22 (3.0) 1.39 (5.24) GPA 10.59 (3.2)

R2 .449 .350 .334

GPA=grade point average.

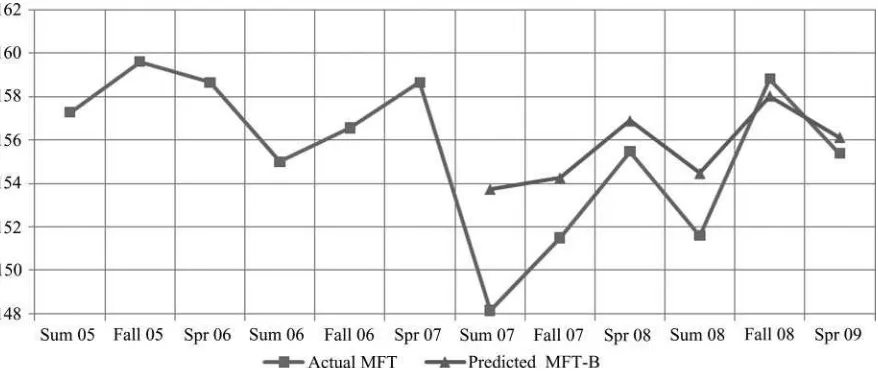

FIGURE 1 Performance of all cohorts (color figure available online).

The regression coefficients are shown in Table 6. Figure 1 plots the actual MFT-B scores for the entire cohort over the period of the study along with the out-of-sample prediction from summer 2007. An examination revealed that predicted scores were higher for summer 2007 and fall 2007 but lower thereafter. Therefore, it is possible to conclude that from spring 2007 to spring 2009 students overperformed on the MFT-B test. However, if the extra credit effect was added to the semesters during which it was offered (using Table 3), students underperformed from summer 2007 to spring 2008 and in fall 2008, slightly overperformed in summer 2008, and did just as expected in spring 2009.

Figure 2, for prediction for Subcohort 1, shows that stu-dents in this cohort generally overperformed or did as ex-pected from fall 07 to spring 09. However, if the extra-credit effect is added to the semesters it was offered students

over-performed in spring 2008, underover-performed in summer and fall 2008, and performed as expected in spring 2009.

Figure 3, for prediction for Subcohort 2, shows that stu-dents in this cohort generally underperformed during the whole period from the summer 2007 to spring 2009, except from fall 2008. For this cohort, the extra credit was not sig-nificant.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Using MFT-B scores collected from summer 2005 to spring 2009, we demonstrated how institutions can establish goals and expectations based on unique student characteristics for graduating classes or individual majors, as well as how to make empirically supported judgments as to whether

FIGURE 2 Performance of Subcohort 1 (color figure available online).

12 A. BIELINSKA-KWAPISZ ET AL.

FIGURE 3 Performance of Subcohort 2 (color figure available online).

MFT-B performance was above or below the unique expec-tations for those cohorts at that institution. Although com-parisons of institutional performance to national norms is irresistibly appealing, the procedure described in this study would seem considerably more relevant to those interested in a more complete and accurate understanding relative per-formance and value added at their institution. As this study demonstrated, across four separate subcohorts in the same college at the same institution, when student characteristics are taken into consideration, it is possible to conclude that over time one subcohort consistently overperformed and one had mixed performance above and below expectations, with performance for at least one period at the level of expec-tation. Although it is intuitively satisfying to contend that higher scores are better, it can also be the case to conclude that given the characteristics of a subcohort that a high score actually represents less value added and relative performance than a subcohort with lower MFT-B average score.

As can been seen in Table 2, in this study some subco-horts (academic majors), attracted students with higher ACT scores. Recalling that ACT scores can be considered a proxy for cognitive intelligence (Koenig et al., 2008), Table 2 also shows that in this study, consistent with previous research, ACT scores had a high correlation with MFT-B scores. To be sure, the models described in this study did not explain all the variation across cohorts; however, to be either excited or disappointed by a particular MFT-B cohort score requires consideration of the dispositional characteristics of the stu-dents who received those scores.

Limitations

It would be possible, if equivalent student characteristic data were available from other institutions, to use the methods described in this study to compare MFT-B scores across dif-ferent colleges and universities. At this point, the primary

utility of the technique, given that institution variables would be held constant, lies in its ability to compare MFT-B per-formance of within-institutional cohorts to the expectations signaled by student characteristics and disposition, most no-tably aggregated ACT scores and GPAs.

As previously noted, ETS, publisher of the MFT-B, refers to the use of subject matter experts to produce the MFT-B along with certain rigorous statistical analyses to see whether each question yields the expected results (ETS, 2009). Using empirical methods to examine the version of the MFT-B in-tended for sociology students, Szafran (1996) found support for the reliability and validity of the instrument; however, the absence of equivalent validity studies specifically in re-gard to the MFT-B is a concern (Allen & Bycio, 2007; Par-menter, 2007) and limits the value of the findings, although not necessarily the methodology. Validity studies, along with replications of this study in other institutional settings, will advance the understanding of the value of assessment testing generally and the utility of the MFT-B specifically.

REFERENCES

Allen, J. S., & Bycio, P. (1997). An evaluation of the educational testing service major field achievement test in business.Journal of Accounting

Education,15, 503–514.

Bean, D. F., & Bernardi, R. A. (2002). Performance on the major field test in business: The explanatory power of SAT scores and gender.Journal of

Private Enterprise,17(2), 172–178.

Bielinska-Kwapisz, A., Brown F. W., & Semenik, R. J. (2010, August).

Is higher better? Determinants and comparisons of performance on the

Major Field Test–Business. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the

Academy of Management, Montreal, Canada.

Bin, O. (2004). A prediction comparison of housing sales prices by paramet-ric versus semi-parametparamet-ric regressions.Journal of Housing Economics,

13, 68–84.

Black, H. T., & Duhon, D. L. (2003). Evaluating and improving student achievement in business programs: The effective use of standardized assessment tests.Journal of Education for Business,79, 90–98.

Bycio, P., & Allen J. S. (2007). Factors associated with performance on the educational testing service (ETS) major field achievement test in business (MFT-B).Journal of Education for Business,82, 196–201.

Educational Testing Service. (2009). A guided tour of the

Ma-jor Field Tests. Retrieved from

http://www.ets.org/Media/Tests/MFT-B/demo/MFT-Bdemoindex.html

Greene, W. H. (2003).Econometric analysis (5th ed.). New York, NY: MacMillan.

Ismail, Z., Yahya, A., & Shabri A. (2009). Forecasting gold prices using multiple linear regression method.American Journal of Applied Sciences,

6, 1509–1514.

Koenig, K. A., Frey, M. C., & Detterman, D. K. (2008). ACT and general cognitive ability.Intelligence,36, 153–160.

Martell, K. (2007). Assessing student learning: Are business schools making the grade?Journal of Education for Business,82, 189–195.

Mirchandani, D., Lynch, R., & Hamilton, D. (2001). Using the ETS major field test in business: Implications for assessment.Journal of Education for Business,77, 51–55.

Parmenter, D. A. (2007). Drawbacks to the utilization of the ETS major field test in business for outcomes assessment and accreditation.Proceedings

of the Academy of Educational Leadership,12(2), 45–55.

Rook, S. P., & Tanyel, F. I. (2009). Value-added assessment using the major field test in business The Free Library. Retrieved from http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Value-added assessment using the major field test in business.-a0219062370

Singh, J., Knapp, H. V., & Demissie, M. (2004). Hydrologic modeling of the Iroquois River watershed using HSPF and SWAT.Journal of the

American Water Resources Association,41, 343–360.

Stoloff, M., & Feeney, K. J. (2002). The major field test as an assessment tool for an undergraduate psychology program.Teaching of Psychology,

29, 92–98.

Szafran, R. F. (1996). The reliability and validity of the major field test in measuring the learning of sociology.Teaching Sociology,24(1), 92–96. Zeis, C., Waronska, A., & Fuller, R. (2009). Value-added program

assess-ment using nationally standardized tests: Insights into internal validity issues.Journal of Academy of Business and Economics,9(1), 114–128.