Information Systems in Healthcare

Gordon D. Brown, Tamara T. Stone, and Timothy B. Patrick

Frederick J. Wenzel

University of St. Thomas

G. Ross Baker, Ph.D.

University of Toronto

Sharon B. Buchbinder, R.N., Ph.D.

Towson University

Caryl Carpenter, Ph.D.

Widener University

Leonard Friedman, Ph.D.

Oregon State University

William C. McCaughrin, Ph.D.

Trinity University

Thomas McIlwain, Ph.D.

Medical University of South Carolina

Janet E. Porter, Ph.D.

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Lydia Reed

AUPHA

Louis Rubino, Ph.D., FACHE

California State University–Northridge

Dennis G. Shea, Ph.D.

Pennsylvania State University

Dean G. Smith, Ph.D.

University of Michigan

Mary E. Stefl, Ph.D.

Trinity University

Linda E. Swayne, Ph.D.

University of North Carolina–Charlotte

Douglas S. Wakefield, Ph.D.

OF INFORMATION SYSTEMS

IN HEALTHCARE

Gordon D. Brown

Tamara T. Stone

Timothy B. Patrick

Health Administration Press, Chicago, IL AUPHA Press, Washington, DC

at (312) 424-9470.

This publication is intended to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold, or otherwise provided, with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

The statements and opinions contained in this book are strictly those of the author(s) and do not represent the official positions of the American College of Healthcare Executives, of the Foundation of the American College of Healthcare Executives, or of the Associa-tion of University Programs in Health AdministraAssocia-tion.

Copyright © 2005 by the Foundation of the American College of Healthcare Executives. Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. This book or parts thereof may not be reproduced in any form without written permission of the publisher.

09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Strategic management of information systems in healthcare / Gordon D. Brown, Tamara Stone, and Timothy Patrick, editors.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-56793-242-8

1. Medical informatics. 2. Health services administration. I. Brown, G. D. (Gordon D.), Ph.D. II. Stone, Tamara. III. Patrick, Timothy B.

R858.S773 2005 651.5'04261—dc22

2005046103 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American Na-tional Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Ma-terials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. ∞

Acquisitions editor: Audrey Kaufman; Project manager: Melissa Rompesky; Cover de-signer: Trisha Lartz; Layout editor: Amanda Karvelaitis

Health Administration Press Association of University Programs A division of the Foundation in Health Administration

of the American College of 2000 N. 14th Street

Healthcare Executives Suite 780

One North Franklin Street Arlington, VA 22201

Suite 1700 (703) 894-0940

v List of Figures and Tables xi

Preface xiii

Acknowledgments xvii

1 Introduction: The Role of Information Technology in

Transforming Health Systems . . . .1

Gordon D. Brown, Ph.D.

PART I The Contribution of Information Technology to Organizational Strategy: Integrating the Clinical and Business Functions

Introduction to Part I . . . .27

2Information Strategy Related to Enterprise and Organizational Strategies . . . .31

Tamara T. Stone and Gordon D. Brown

3 Organizational Accountability for Clinical Outcomes:

The Coming of the Corporation . . . .51

Gordon D. Brown and Suzanne A. Boren

4 Information Strategy Empowers Organizational Strategy . . . .79

Tamara T. Stone

5 Managing Data, Information, and Knowledge . . . .99

Timothy B. Patrick

PART II Information as Enterprise Strategy: The Strategic Use of Information Resources

Introduction to Part II . . . .119

6 Aligning Information Strategy and Business and Clinical Strategies:

Information as a Strategic Asset . . . .121

7 E-Health and Consumer Informatics . . . .149

George Demiris

8 Genomic Medicine: Informatics Implications and Opportunities . . .171

Mark A. Hoffman

PART III Information Strategy: Managing Information Resources

Introduction to Part III . . . .191

9 Investing in Information Technology . . . .195

Keith E. Boles and Michael J. Cook

10 Managing Information Technology Services . . . .223

Anthony N. Duminski and Timothy B. Patrick

11 Information Security and Ethics . . . .237

Kenneth W. Lobenstein

PART IV Building a Healthcare Information Infrastructure

Introduction to Part IV . . . .259

12 Conclusion: Managing Informatinon Technology in the Future . . .261

Gordon D. Brown and Jim Adams

Index 293

About the Editors 307

vii List of Figures and Tables xi

Preface xiii

Acknowledgments xvii

1 Introduction: The Role of Information Technology in

Transforming Health Systems . . . .1

Gordon D. Brown

Information as a Transforming Technology, 2; IT in Healthcare Organiza-tions, 8; The Constraining Potential of IT, 17; Information Skills for Health Systems Leaders, 19.

PART I The Contribution of Information Technology to Organizational Strategy: Integrating the Clinical and Business Functions

Introduction to Part I . . . .27

2 Information Strategy Related to Enterprise and Organizational Strategies . . . .31

Tamara T. Stone and Gordon D. Brown

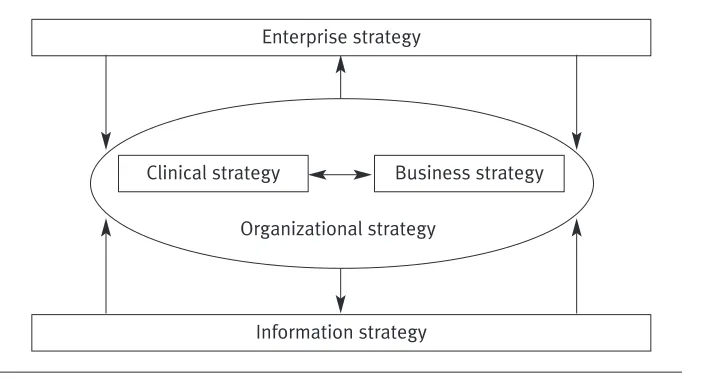

The Strategy Network in Healthcare Organizations, 32; Information Strategy Related to Enterprise and Organizational Strategies, 39; IT as a Social Good, 46.

3 Organizational Accountability for Clinical Outcomes:

The Coming of the Corporation . . . .51

Gordon D. Brown and Suzanne A. Boren

Integration of Clinical Strategy with Business Strategy: The Coming of the Corporation, 53; Information Strategy: Clinical Decision Support Systems, 62; Aligning Information Strategy with Clinical Strategy, 71.

4 Information Strategy Empowers Organizational Strategy . . . .79

Tamara T. Stone

86; Transforming Intangible Assets Through IT, 89; Commitment-Based Management and the Human Capital of IT Workers, 93.

5 Managing Data, Information, and Knowledge . . . .99

Timothy B. Patrick

Data, Information, and Knowledge: A Philosophical View, 100; Controlled Representations and Interoperability of Data, Information, and Knowledge, 101; Interoperability and Knowledge Management, 107; The Semantic Web, 109.

PART II Information as Enterprise Strategy: The Strategic Use of Information Resources

Introduction to Part II . . . .119

6 Aligning Information Strategy and Business and Clinical Strategies:

Information as a Strategic Asset . . . .121

Kenneth D. Bopp and Gordon D. Brown

Value Migration in Healthcare, 122; Consumer Empowerment in Health Services, 131; Strategic Leadership in Healthcare Organizations, 138; The Coming Paradigm Shift in Integrated Health Delivery Systems, 143.

7 E-Health and Consumer Informatics . . . .149

George Demiris

Implications of IT for Empowering Individuals and Communities, 150; Review of Patient-Centric Systems, 152; Challenges for e-Health Applica-tions, 158; Success Factors for e-Health, 161; Considerations for the Fu-ture, 164.

8 Genomic Medicine: Informatics Implications and Opportunities . . .171

Mark A. Hoffman

Genomic Medicine, 172; Current State, 172; Emerging Trends, 181.

PART III Information Strategy: Managing Information Resources

Introduction to Part III . . . .191

9 Investing in Information Technology . . . .195

Keith E. Boles and Michael J. Cook

The Challenge of Delivering Value, 196; A Valuation Framework for IT, 200; Tools for Evaluating IT Investments, 207; Process for Evaluating IT Investments, 211; Behavioral and Other Noneconomic Issues, 218.

10 Managing Information Technology Services . . . .223

IT Governance and Leadership, 224; Strategic IT Planning, 226; Individual Project Planning and Management, 228; IT Department Organization, 229.

11 Information Security and Ethics . . . .237

Kenneth W. Lobenstein

A Security Framework, 238; Aspects of a Basic Security Program, 242; A Zone-Based Architecture, 252.

PART IV Building a Healthcare Information Infrastructure

Introduction to Part IV . . . .259

12 Conclusion: Managing Information Technology in the Future . . .261

Gordon D. Brown and Jim Adams

The Seeds of Change: Transforming the U.S. Health System, 263; Develop-ment of an Integrated Information System, 274; Personal Health Record, 278; Clinical Information Networks, 282; Innovative Business Models, 283.

Index 293

About the Editors 307

xi

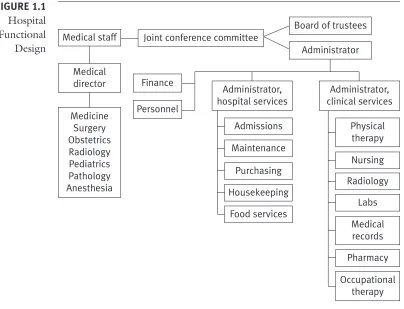

Figure 1.1 Hospital Functional Design

Figure 1.2 Skills Needed by Health Systems Leaders for IT Decisions

Figure 2.1 Strategic Integration of Healthcare Organizations

Figure 2.2 Maxims for Information Technology

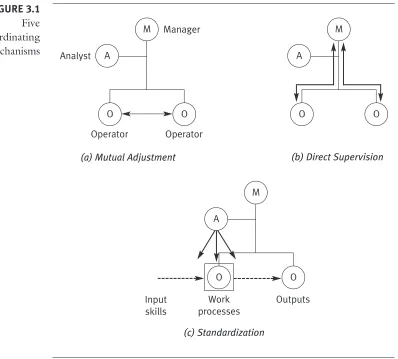

Figure 3.1 Five Coordinating Mechanisms

Figure 3.2 Clinical Guideline for Diabetic Retinopathy Screening and

Treatment

Figure 3.3 Clinical Pathway for Asthma Management Involving Patient

and Parents

Figure 3.4 Contemporary Integrated Health System

Table 5.1 Alternative Definitions of Knowledge Management Retrieved

from Google.com

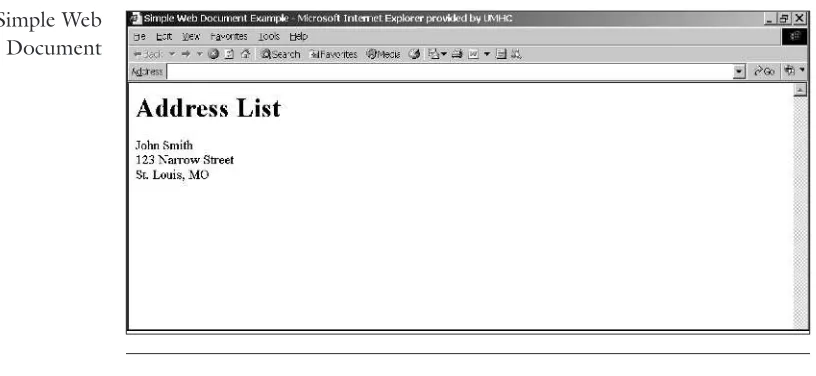

Figure 5.1 Simple Web Document

Figure 5.2 Sample HTML Document

Figure 5.3 Sample XML Document

Figure 5.4 RDF Triple in XML

Figure 6.1 Sociocultural Network of Health Systems

Figure 6.2 Future Sociocultural Business Systems

Table 8.1 Web Sites Providing Genomic Information for Clinicians and

Patients

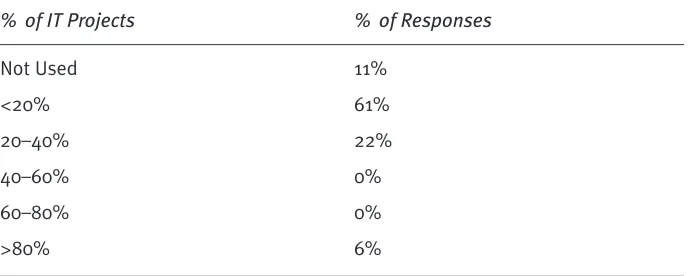

Table 9.1 Percentage of IT Projects Subjected to Formal Evaluation

Process

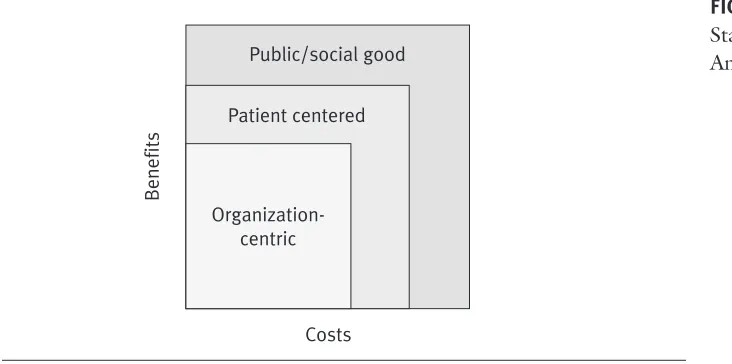

Figure 9.1 Evaluation Framework for IT

Figure 9.3 Stakeholder Matrix

Figure 9.4 Risk Adjustments to Discount Rate

Table 9.2 Example of EVA Sensitivity Analysis

Figure 10.1 Sample IT Vision Statement

Table 11.1 Development and Change-Control Security Issues

Table 11.2 Forms of Intellectual Property

Figure 11.1 Zone-Based Approach to System Protection

Figure 12.1 CHI Initiative Data and Information Standards

xiii

T

his book explores how healthcare organizations can utilize advanced in-formation technology (IT) to achieve high levels of operational per-formance and strengthen their market position. It considers health in-formation systems from an organizational perspective, integrating the science of IT, medicine, and nursing practice within the context of complex adaptive systems. The book provides a conceptual framework for considering how IT can be used to fundamentally transform clinical work processes and integrate the clinical and business functions to achieve a coherent organizational strat-egy. The framework draws on a body of organizational and systems theory and incorporates evidence from information and clinical sciences. The book takes an application approach, drawing on current operational and policy issues and supported with a rapidly growing body of evidence on how IT can be used to transform health systems function and improve clinical and business perform-ance.Because of its grounding in theory and research evidence, the book is well designed for use in graduate courses in health management, medical in-formatics, medicine, and nursing and other health professions. Practicing health professionals can use the book effectively as well, either as a general reference or by focusing on the conceptual and applied material as a frame-work for problem solving and strategy development. Starting with Chapter 2, each chapter features a case study drawing on actual situations to introduce and apply the concepts. Readers are encouraged to return to the case for ad-ditional insight as they read through the chapter. These chapters also include a problem solving scenario that draws on the case and applies and integrates material from the chapter.

being accountable for clinical outcomes. Information technology can enable this shift, but there is no evidence to suggest that IT alone will produce it.

Part II focuses on information strategy related to enterprise strategy, or how an organization uses information to position itself in a competitive market and respond to environmental change. The issues examined include the use of information as a strategic asset, and a number of applications are discussed. Specific strategies are selected and discussed in some detail, includ-ing knowledge management as an organizational strategy, consumer infor-matics, the role of e-health and web-based technologies, and the impact of genomic medicine on health behaviors and services delivery.

Part III focuses on managing information resources. The editors feel it necessary to provide a detailed discussion of IT from the perspectives of operations management in Part I and strategic management in Part II before addressing the specifics of managing information resources. The earlier chap-ters provide the essential context for considering the investment in and man-agement of information resources. This section includes chapters on the ef-fective management of information resources, investing in IT, IT structure and staffing, and information security and ethics.

Part IV provides a broader context for thinking about how IT might affect the health system in the future. It is policy oriented and includes a comparative analysis drawing on how information has been applied in other service industries and health systems in other countries. It considers how IT in health might spawn fundamentally new ways of thinking about the indus-try. Discussions include increasing entrepreneurial behavior in start-up com-panies and considering health information from a global perspective. In-cluded in the discussion is an assessment of current U.S. policy initiatives to develop a national health information infrastructure.

Information is recognized as an important technology and one of the latest technologies to be brought to the health system. This recognition has given rise to many clinical and business applications and is reported in the lit-erature. Information, however, is more than just the latest technology to af-fect the health system. It is one of the few resources that increase in volume and value as it is used. Its value is in its use, as with any resource, but by its use adds resource. Consequently, traditional models to explain the econom-ics and strategy of investing in a technology do not fit information technol-ogy. This book explores IT within a new paradigm applied to health organi-zations and systems.

of the conflict with traditional professional roles. The technical focus of early applications has included primarily information technologists and nursing and medical professionals.

xvii

T

he editors gratefully thank our many academic and practicing colleagues for their insights and contributions to our understanding of the appli-cation of IT in healthcare organizations. Many of them provided feed-back and made useful suggestions on this manuscript. We also acknowledge and express our sincere thanks to Christopher R. Brink, Lillian C. Folk, Can-dace Garb, Linda Huether, Annamarie Mantese, and David Moxley for their considerable assistance in manuscript organization and preparation. Their contributions greatly improved the quality of the book.1

1

INTRODUCTION: THE ROLE OF

INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY IN

TRANSFORMING HEALTH SYSTEMS

Gordon D. Brown

Chapter Outline

1. Information as a Transforming Technology 2. IT in Healthcare Organizations

3. The Constraining Potential of IT

4. Information Skills for Health Systems Leaders

Learning Objectives

1. Understand the role of IT as it affects work process design and organi-zational strategy.

2. Understand the issues facing healthcare organizations regarding the ap-plication and use of IT.

3. Apply knowledge about IT to make informed operational and strategic decisions in healthcare organizations.

4. Synthesize how the clinical and business functions in healthcare organi-zations are structured and how IT can facilitate effective business and clinical decision making.

5. Evaluate the potential and limitations of IT in a functioning healthcare organization.

Chapter Overview

The application of advanced information technology (IT) to improve health system performance has probably generated more hope than any development in the health system. Yet, somewhat perversely, IT has at the same time fre-quently failed to meet expectations. Those studying the problem define it in different ways and propose varied solutions. Some chief information officers

Key Terms

Business process redesign

Clinical process redesign

Healthcare value chain

Genomic medicine

Information vocabularies and databases

Information architecture

Clinical decision support systems

(CIOs) view it as a financial problem caused by underinvestment in IT by healthcare organizations. Others feel that it is a vendor problem, in that soft-ware vendors cannot deliver on their promises. Vendors claim that applying in-formation systems (IS) to the health field is difficult because of the exceedingly complex nature of health services delivery. Chief financial officers say the re-turn on investment is far below expectations at any level of investment. Chief executive officers (CEOs) observe that complexity and cost increase exponen-tially as the application progresses and that no end is in sight. They wish the problem would go away, but it won’t. Doctors, nurses, and other health pro-fessionals range from enthusiastic to indifferent to hostile when considering the application of IT to their work.

Which view of the IT world is correct? The fact that the problem touches almost everyone in the organization and is viewed so differently sug-gests that it is systemic in nature. The argument that applications in health sys-tems are more difficult because health services and health syssys-tems are so com-plex is probably true. The comcom-plexity of the system could explain the pace of development, but not the failure to apply and widely use systems that have been tested and proven. This suggests that the issue is not primarily in the new technology or how it is being implemented in healthcare organizations. These may be problems, but the issue is much more complex. It suggests a failure to understand or accept changes in business and clinical processes that are en-abled by IT. Information is an enabling technology. Its design and application in organizations must be consistent with the design of the work processes it is intended to facilitate. Lacking that, the technology will fail regardless of the level of investment, vendor, system capacity, computing speed, or size and qualifications of the IT staff.

The application of IT has demonstrated major positive outcomes in other industries (Andersen and Segars 2001; Chen and Zhu 2004; Oliner and Sichel 2000). Some encouraging achievements in the performance of health-care organizations have been credited to IT. The critical factor is the consis-tency between how IT is designed and managed and the design of the work processes it supports.

Information as a Transforming Technology

are based on the assumptions of the industrial revolution—the second wave— and thus may be irrelevant in an information and technology society. He ob-serves that although we are in the information and technology age, we still typ-ically function with the mind-set of the industrial revolution. Current and future organizations and systems, he proposes, need to be built on assumptions of the technology and information age. The problem is that we do not have good models for doing this. We know only that our current models do not work very well.

Financial and other sectors of society provide emerging examples of how the new age might be structured and function. The structures that have emerged are innovative but can be understood only within the context of the process by which they were derived. The process that led to the development of VISA as an organizational model is a good example. Early concepts of plas-tic charge cards were as extensions of existing banking institutions and processes. Individual banks envisioned incorporating new optical scanning and computer technology to develop charge cards as an alternative to writing checks. They were considered to constitute a limited market appealing to a certain clientele. Charge cards were designed to be unique to each bank and used as a means of differentiating them in the market. The application of charge cards was imposed over a traditional banking structure that never en-visioned the transforming potential of the information age. The hospital in Case 1.1 defined the problem as needing to automate an aspect of the billing system but installed software that was based on the assumption of a re-designed process of managing the revenue cycle.

Where the established banking industry saw the charge card as an alter-native to writing checks, some saw it as the basis for electronic banking and others as a basis for a totally integrated financing system. In order for the new technology to work, the industry had to develop fundamentally new processes and structures. Change theory describes this phenomenon as double-loop learning. New structures do not evolve from structures of the past but rather are innovative, based on new sets of assumptions. Banks could not differenti-ate themselves through their individualized charge cards and so would have to cooperate to develop an electronic system they could use collaboratively. VISA did not evolve from any previous structure or logic of the financial community but instead used its understanding of the transforming power of IT to envision a new order. The nature of organizational innovation and the demands it places on leaders is described by VISA’s founder, Dee Hock, as “chaordic,” combining chaos with order (Hock 1999). He concludes that organizations are built to bring order but must live and thrive in a world of chaos. If this is so, we must build organizations to perform in that environment.

Health Valley Hospital had operated on a financial system from a minor software vendor for many years. The hospital reviewed the cost and made judgments about the system, deciding that it was not keeping up with the needs of the organization. Management felt it was time for a new patient and financial accounting system. This action was taken to reduce costs and, more importantly, to improve the finan-cial performance of the organization and increase its sophistication in finanfinan-cial analysis.

After a thorough process of determining and documenting requirements, a multidisciplinary group of executives and managers evaluated all of the major healthcare software vendor offerings. They selected a well-known full-suite prod-uct of patient and general accounting, accounts payable and receivables man-agement, payroll, decision support, and electronic commerce. The application suite was installed primarily by the staff of the hospital with support from the vendor.

The implementation of the system was a technical success, but the ap-proach of the business leaders was to automate the current business processes with the new system. They did not fully evaluate the new system’s impact on oper-ations. The electronic commerce capability had advanced edit and screening capa-bility well beyond the capabilities of the prior system. This system checked the components of a bill against the billing system entries, against the medical records abstracting system, and finally against edits used by the Medicare intermediary that adjudicated and paid Medicare claims. The older system only checked for data integrity within the billing system and had no capability to replicate the editing done by the intermediary.

The implementation had an immediate and significant impact. Claims that used to go out the door to the insurers were now failing to pass the edit checks. No process was in place to reconcile the issues between the billing and medical records offices. The edits became more robust and caught claims at a more de-tailed level. Finally, claims that used to leave the organization and go to Medicare

CASE 1.1

Health Valley Hospital Upgrades IT

System

might be expected to be a leading sector in the third-wave transformation. On the other hand, being an information-dominated industry might make the potential of change greater but the probability of change less. Evidence supports the fact that information organizations are difficult to change in part because the information infrastructure has been applied to existing processes and structures (Keen 1994). Toffler (1980) speculates that higher education, being in the information and technology business, controlled by profession-als, lacking strong competition, and steeped in tradition, would be slowest to change. He predicts that some universities would rather die than change, and so they will. This description might apply to healthcare organizations as well.

The Role of IT in Organizations

There are two basic approaches to the application of IT to healthcare organ-izations: to automate existing processes or to enable the transformation of processes. Neither is right or wrong, but they are very different in approach

Automation of existing

after a significant time delay if they were returned because of edit failures were being rejecting on site immediately.

The result of this process was a rapid growth in rejected claims, over-whelmed business office staff, and dramatically increased dollars in accounts re-ceivable (AR). Prior to conversion to the new system, the days in AR averaged in the mid-70s. This increased significantly as management tried to cope with the problem, until days in AR reached more than 110.

The approach taken to deal with the problem was to use a multidisciplinary, multilevel team assisted by outside consultants who reviewed and redesigned the entire business work flow. The software vendor was also brought in to help coordi-nate the work flow changes with the capabilities of the software system. New roles were created, new middle management was hired, and training in new processes was implemented. The linkages among the business, medical records, and regis-tration offices were dramatically strengthened with audits implemented to support the evaluation of data quality. Additionally, a change management committee was established to discuss, evaluate, and approve changes that needed to be made to business processes as well as computing systems. Effectively, the new integrated computer system forced the organization to behave more like an integrated system itself and less like a collection of departments.

The end result of the new system implementation along with the new busi-ness process improvements is impressive. Days in AR have dropped dramatically and now average in the mid-30s, close to best in class within the geographic re-gion. The charges billed and dollars collected have improved dramatically. Days of cash on hand have grown by 50 percent in less than two years. Finally, the organi-zation’s bottom-line profitability has improved.

Problem Solving 1.1 discusses the lessons to be learned from Health Val-ley’s experience.

—Lawrence Sharrott, CIO, AtlantiCare Health System, and president, InfoShare, Inc., Atlantic City, NJ

The application of IT overlaid how hospitals and clinics were structured and functioned.

Early applications in hospitals and clinics were designed to automate existing internal processes. Organizational leaders were reluctant to invade and alter the clinical decision process. In part this reluctance was because most leaders had been trained in and were oriented only to the business func-tion and it challenged hundreds of years of separafunc-tion of the clinical funcfunc-tion from organizational interference. The availability of information to assess clinical outcomes and improve clinical processes frequently exceeded the ca-pacity or commitment of the organization to use it in such a manner. Hospi-tals and clinics maintained their existing hierarchical functions or invested in clinical information systems seemingly under the assumption that new data systems would change clinical work processes. This assumption has not proven to be true.

Nearly absent from the application of IT in healthcare organizations is the management of the clinical process from the perspective of the patient and patient-centered care. The potential of advanced IT to enable the transfor-mation of clinical processes across professionals, departments, organizations, and systems is considerable but has generated little interest from organiza-tions or health professionals.

This book focuses on the use of IT as an enabling technology for transforming work processes. The application of IT in such transformations has been well developed in some product and service industries. In these in-dustries the application of advanced IT is viewed as an enabling technology supporting innovative process redesign. Evidence shows that IT investment by organizations has not been effective as a means of initiating or stimulat-ing business process design (Broadbent, Weill, and St. Clair 1999; Collins 2001). Such investments have resulted in information capacity that does not produce the anticipated outcomes or expected return on investment. Re-sponsibility for the failure is frequently directed at the software, CIO, IT staff, or underinvestment. The solution is frequently directed at one or more of these “problems,” but evidence suggests that none of these factors consti-tute the real problem. More likely, the problem is that the enabling technol-ogy was purchased without sufficient understanding of or commitment to work process redesign (see Problem Solving 1.1).

Work Process Redesign

The purchase of advanced IT without a commitment to work process redesign can be a wasted investment by the institution. The total cost to the institution might even be greater than the direct cost of the IT system itself. The applica-tion of IT to automate existing systems can act as a constraint to later attempts at redesign (Keen 1994). The strategy of installing and institutionalizing new

technology prior to process redesign can contribute to the failure of the re-design by further freezing current processes into place. Furthermore, change that occurs later will be much more complex and costly. On the other hand, acquiring IT as a means of producing the redesign is likely to fail.

Organizations committed to innovative work process redesign have found the investment in IT essential (Caron, Jarvenpaa, and Stoddard 1994). Those that have tried to pursue such a strategy without a strong IT infrastruc-ture designed to support it have failed or had limited success. Information technology has been found to be an essential enabling technology when closely integrated with the redesign of the business or clinical functions. When IT is incorporated as an enabling technology in process redesign, issues of ac-ceptance and use are diminished. These institutions do not use IT develop-ment to overlay existing work processes but rather as the enabling technology to fundamentally transform them. This is the strategy of Wal-Mart (Furey and Diorio 1994), VISA (Hock 1999), and other companies using IT to support a transformation of previous business processes.

Considerable evidence describes how IT can be used to enable the fun-damental redesign of work processes that produce exceptional levels of indus-trial operating efficiency and strategic advantage. Scholars and executives, par-ticularly those grounded in management IS, have established a rich literature on innovative business process redesign as a means of achieving superior busi-ness performance. Process redesign is differentiated from process improve-ment, depicting fundamentally new ways of considering business functions. Process redesign has also been referred to as process reengineering, requiring vision and conceptual skills to develop innovative solutions for existing prob-lems. True innovation requires the conceptual reorganization of problem sit-uations (Shull, Delbecq, and Cummings 1970, 71–94). This assumption un-derpins the work of Deming, Juran, and others in using process redesign and process improvement as a means of reaching Six Sigma levels of quality.1

PROBLEM

SOLVING 1.1

Health Valley Hospital Upgrades IT System In Case 1.1 it was only through the installation of a new software system and

im-plementation of new business process that outstanding results were achieved. The lesson to be learned from this experience is how to use new technology to transform business processes without being forced to do so by poor outcomes.

• The improvements noted in Case 1.1 could not have been achieved by the im-plementation of new technology alone. As a matter of fact, the new system highlighted and amplified the problems with the old processes.

• Implementing new processes without a new software system could not have produced the same results. Many of the processes now in place could not be provided or supported with the older system.

The application of scientific principles and technological advances to fundamentally redesign business processes to achieve superior outcomes did not really take hold in the United States until the 1980s, although the sci-ence has existed for much longer. This lag occurred for two reasons. First, businesses enjoyed relative prosperity after World War II and did not perceive the need to reform their business processes. Second, the principles of scien-tific management were not emphasized in corporate leadership or business schools, which relied on tradition consisting of “myths, hunches, gut feel-ings, intuition and knee-jerk reactions,” instead of scientific evidence, to im-prove business processes (Spare 2000). Global competition changed the mar-ket and nature of the competition. Businesses using traditional management approaches and theories found they could no longer compete.

IT in Healthcare Organizations

Evidence of how advanced IT can facilitate work process redesign is com-pelling. The level of evidence over time and across a large section of the serv-ice and product industries provides considerable support for application of advanced IT to healthcare organizations. The evidence supporting the en-abling power of IT to improve work processes raises questions of why such a lag exists in the health industry. Are healthcare organizations more complex, resource rich, or poorly managed, or are there other factors to consider?

Healthcare organizations present a particularly difficult challenge be-cause of their traditional structure and assumptions about work processes, es-pecially clinical work processes. Patients enter the hospital or clinic based on a specific need, typically seeking treatment of some disease symptom. The pa-tient encounters the system, receives a service, and exits the organization. Health services are viewed by the institutions more as a commodity than as a continuing commitment. Services are evaluated on the basis of the quality of the given service and level of satisfaction reported by the patient. Patients, on the other hand, increasingly view health services as a continuous process be-cause of the increasing rate of chronic diseases and changing attitudes about healthcare. Under these conditions, information on health status, disease his-tory, treatment hishis-tory, and health risks is shared among all health providers and with the patient. Healthcare organizations are institution-centric, which also characterizes their information systems. Physicians frequently become focused on episodic illness, probably in part because the information systems that support their decision making are designed in this manner.

The dominant business logic is based on the assumptions of economies of scale of equipment and personnel. This is the logic for centralizing invest-ments in functional departinvest-ments. The actual clinical functions are carried out by health professionals working across functional units based on the needs of each patient during the episode of care. Physicians have been structurally sep-arate from the organization and are highly autonomous in working with the patient to determine service needs and the structure of the overall clinical process. The hospital represents a single stage of production, and the clinical function is structured around that stage of care. It is based on institutional care, not the patient, as the unit of analysis. The clinical function from the perspective of the patient is considered outside the purview of most health-care organizations. Information technology has been developed within the hospital around the clinical function, separate from the business function. The traditional structures of the business and clinical functions have defined the design of information systems to support them.

Transforming the Business Function

The business function in healthcare organizations has been focused on in-ternal operations and operational efficiency. Business operations consisted of relatively simple processes of scheduling, billing and collections, accounting, budgeting, personnel, payroll, purchasing, inventory, and supply. Computer applications in business processes first automated these back-office opera-tions, which resulted in increased processing speed and greater efficiencies. They were characterized as data processing functions and traditionally lo-cated in departments bearing that name.

Since the late 1940s, business operations have became increasingly complex because of third-party reimbursement, legal issues, training re-quirements and certifying agencies, proliferating public regulations, and services marketing. Information technology was managed from the finance department because financial data were an ideal application for data process-ing. Financial reporting consisted of easily automated standardized measures and repetitive processes. Financial management was also a dominant busi-ness function in healthcare organizations that required the integration of in-formation from various business departments. Dwindling financial margins for many healthcare organizations have exerted increased pressure to better manage the business function. To date most efforts have been to manage ex-isting internal business operations more efficiently rather than redesign the business function. Particular attention is being paid to managing the rev-enue cycle and areas affecting profit-and-loss statements. On the cost side, organizational leaders have sought greater efficiencies by consolidating or outsourcing operations and initiating collaborative arrangements such as group purchasing. Many applications that have demonstrated economies in other industries, such as bar coding, have been slow to develop in healthcare

organizations because vendors have not made this technology available to health providers.

The business function has been structured around a functional design that includes the business departments and nursing and clinical support serv-ices (see Figure 1.1). Early applications of IT in healthcare organizations to nursing and clinical support departments were for business operations. The application of IT overlaid how hospitals and clinics were structured and func-tioned.

Interest by healthcare executives in redesigning business processes with ven-dors and other collaborative organizations has lagged far behind other indus-tries. The redesign of business processes broadens the perspective of internal business operations and places them within the context of strategic partner-ships for managing the business function. Process redesign in health institu-tions will be dependent on advanced IT as it has been in other industries. Like other industries, however, IT will not initiate process redesign.

Burns (2002) and colleagues have provided a useful conceptualization and discussion of supply-chain management in the health field. Burns describes classifications of institutions participating in the healthcare supply chain, or “value chain,” including payers, fiscal intermediaries, providers, purchasers, and

producers (Burns 2002, 23–26). From analysis of the various interrelation-ships among organizations along the value chain, Burns (2002) concludes:

What is lacking, however, is coordinated effort among these parties, wide-spread strategic alliance formation, knowledge sharing, inter-firm trust, and compelling value chains oriented to delivering the greatest customer value at lowest total cost. Indeed some industry executives boldly state that the word partner does not really exist.

Various models have demonstrated considerable economies, such as partnership models for group purchasing (Richardson 1989). Collaborations with suppliers to develop bar coding and inventory management systems show considerable promise. There is little doubt that there are considerable savings yet to be realized. Many of these applications will take a form similar to those in other industries. These applications have been well described and their savings well documented (Byrd and Davidson 2003; Chapman, Gupta, and Mango 1998). Health executives need to draw on what has been learned in these industries to redesign and better manage the business process.

It is difficult to measure the degree of interest in and commitment to business process redesign in the health field, but organizational leaders have tended to spend more time focused on internal operations and managing the revenue cycle than on business process redesign. This is understandable given the relative ease of passing on costs to consumers, but a revenue strategy likely will not be adequate in the future. Providers will no doubt have to deal more aggressively with costs, and pressures will increase to develop innovative solu-tions to business process redesign. Encouragingly, attention has recently been given to supply-chain and other aspects of business process redesign in health-care organizations (Burns 2002, 419–24).

Transforming the Clinical Function

Healthcare organizations need to increase focus on clinical process improve-ment and how IS supporting health professionals, organizations, and sys-tems must change. The clinical function makes up the core technology of healthcare organizations; structuring and managing the clinical process has the greatest potential to improve clinical quality, patient satisfaction, and ef-ficiency. Greater accountability for health outcomes by healthcare organiza-tions has increased the need to structure and manage the clinical process. Managing the clinical function will become much more complex in the fu-ture as chronic care increases, patient expectations change, and genomic in-formation is incorporated into clinical decision making.

The traditional perspective of IT applied to the clinical function has been institution-centric. The clinical function is viewed by hospitals, clinics, and other institutions as medical consultations or procedures, nursing services,

The

and clinical support services related to a given clinical encounter. Clinical support services include pharmacy, laboratory, diagnostic radiology, medical records, and services of other health professionals. A clinical encounter is typically disease oriented and the basis for a patient seeking services from an individual or institution-based health professional. The clinical encounter consists of diagnostic and treatment processes related to an episode of care, usually provided within a given unit of a health facility.

The pattern of automating the clinical function was departmental or func-tional and based on decisions made by department directors. Departments such as pathology saw early applications of electronic IS because they dealt with standardized measures and repetitive processes perfect for IT. Applica-tions were oriented primarily to support internal work processes. Other de-partments developing early IS included pharmacy, radiology, and nursing. Au-tomating various clinical functions was straightforward and widely pursued, albeit at different rates within a given institution and built on different data platforms. The pattern of automating existing processes defined by functional departments continues to be followed by hospitals and clinics, producing im-proved efficiency and accuracy. Many departments used the application of IT to evaluate and improve existing processes. Although the reporting of results from these developments was characterized as process redesign, it might be better characterized as improving existing processes. More accurately, the re-porting of results was oriented to improve work processes, or microprocesses, within functional departments.

As IT became more broadly applied to manage clinical processes, a logical next step was to integrate clinical information across departments to provide information to support decision making at any point in the clinical process. Although logical, this step was exceedingly complex for two reasons. First, hospitals and health institutions are structured around functional depart-ments, not clinical processes, depending primarily on individual health pro-fessionals to integrate the clinical process. There was a need to structure in-formation to support processes that lacked integration. Managers were caught in the fallacy that information could restructure processes. Second, existing databases and IS did not provide a consistent vocabulary, nor were they built on a common information architecture that permitted integrating clinical information. IS vendors and executives understood that they were building IS that would technically not support the integration of clinical in-formation, but the established structure and control systems of health insti-tutions dictated this phase of development. Thus, information was gathered from clinical departments by developing interfaced systems to provide inte-grated, timely, and accurate information. The integration of the various sys-tems with disparate purposes, vocabularies, and data standards has made this step exceedingly complex and costly.

Automation

Hospital and clinical executives, along with IS vendors, concluded that the development of an electronic medical record (EMR) might be the solution to the complex problem of integrating clinical databases. This con-cept was advanced in the 1960s by Larry Weed (1968, 1970) as an effective clinical support technology. The EMR was intended to provide a common data set and a repository for clinical information accessible to all health providers. This strategy was sound and probably essential but also com-pounded the problem because the development of an EMR invites the in-terconnection of all clinical support areas at once, coding historical data and installing the system while continuing to maintain a paper-based system to support current operations. Installation is typically built on unrealistic time frames for bringing applications online. A common problem is trying to do too much at once. The EMR serves as the basis for further developments of electronic systems such as computerized physician order entry systems. These system applications have considerable potential for providing decision support tools for physicians, nurses, and all other health professionals.

Many hospitals have made progress in recognizing the potential of ap-plying integrated clinical information to improve medical and nursing deci-sions and clinical processes. The potential for improvement was identified by the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) studies on patient safety and process im-provement, which note that most medical errors are due to a process break-down, not to individual worker errors (Kohn, Corrigan, and Donaldson 2000; IOM 2001). The availability of clinical information across the treat-ment process and clinical history on which to select evidence-based solutions is essential for clinical process improvement. To be effective, however, organ-ization executives must lead clinical process improvement within their insti-tutions. Installing integrated IS alone will not improve clinical processes.

Current information strategy is essential for integrating and improving clini-cal processes within healthcare organizations. Organizational leaders must also maintain a future focus and consider today the design of IS that will sup-port future applications. Healthcare organizations are spending much time improving existing clinical processes and developing IS to provide technical solutions. What will be the clinical processes of the future? The IOM view of medical errors and clinical quality goes beyond the quality of a clinical en-counter to recognize the entire clinical process and errors caused by under-treatment, overunder-treatment, and inappropriate treatment. The clinical function from the perspective of the patient includes services of all institutions and professionals, inside and outside the health system that are or could be effec-tively involved in the treatment of a given condition or related set of condi-tions. The patient view of the clinical process has not been given much con-sideration by healthcare organizations, which have instead focused on specific clinical encounters. In the future healthcare organizations will likely adopt a more patient-oriented perspective as the result of the increase in complex

chronic diseases and the changing attitudes of consumers. Patient-centered care is a concept heralded by healthcare organizations but frequently viewed within the context of services provided at a given point in the care process. Real patient-centered care views the overall treatment process, as patients view their care.

The clinical function in the health system has consisted historically of individ-ual clinicians functioning independently. Since the 1970s physicians have joined corporations, such as medical groups, and developed closer links with hospitals through more highly structured medical staffs and collaborations such as physician-hospital organizations. These corporate designs enable physicians to negotiate insurance contracts, manage the revenue cycle, and in-crease operational efficiency, but they have not redesigned the clinical process. These structures primarily serve the business function. Physicians have re-tained a high degree of individual autonomy over the clinical function in or-ganizations, even those owned by physicians. Few organizational models have invaded the clinical process per se. Many of the managed care models did so in a crude manner, such as by applying rules for preadmission authorization, but were opposed by clinicians and patients and ultimately discredited. The appropriateness of organizational involvement in clinical process redesign is still the subject of debate and not universally accepted. Certainly, few health-care organizations have strongly committed to clinical process redesign as an organizational goal. Health leaders are ambivalent in general, doubting that process redesign is an appropriate role for organizations. Others see the po-tential and are carefully initiating change from within. The difficulties leaders face include external forces such as reimbursement, governmental regulations, state practice acts, and accrediting agencies that create obstacles and disincen-tives to change. It is clearly not a problem of information or even of the or-ganization, but rather of the health system. The challenge is in changing the system.

The lack of clear commitment to clinical process redesign inherently limits the utility of investment in IT to support the process. Information technology has consistently been found to be an enabling technology for process redesign, but it will not produce process redesign. Investment in IT without the capacity to redesign clinical processes will be a limited invest-ment. There will be an overinvestment in IT that provides technical capacity beyond that needed to manage traditional clinical processes. One resolution is to accept established processes and reduce the investment in IT. This so-lution would bring business operations into balance by reducing the overin-vestment in underutilized information capacity. This would solve the invest-ment problem but suboptimize health system performance. Leading organizations will pursue real innovation by fundamentally redesigning the clinical process. Information thus changes from an overhead cost of opera-tions to a strategic asset for the organization. Evidence suggests that such Process

strategy can produce exceptional levels of quality, satisfaction, and efficiency (Erstad 2003). The degree to which demonstrations of exceptional perform-ance by healthcare organizations will lead others to follow is unclear. There are strong arguments that market forces in the health system have not stim-ulated the level of competition required to force less efficient and effective health institutions to compete in order to survive (Porter and Teisberg 2004). Others argue that public and not-for-profit healthcare organizations will respond to competitive forces to produce increased value to individuals and communities. While this may be a compelling goal, little evidence shows that it generates sufficient incentive to produce internal reform.

Organizations initiating clinical process redesign might find that their clini-cal IS, designed around existing cliniclini-cal processes, do not have the flexibility or capacity to support integrated clinical decision making processes. The field of medical informatics has enabled application of computer technology to ex-isting medical and nursing practices and organizational structures. Medical informatics has been designed largely from the perspective of health profes-sionals, particularly physicians, and how IT can be used to assist clinical de-cisions made within existing decision structures (Friedman et al. 2004, 170). In this regard clinical IS are fundamentally designed to improve existing transactions instead of transforming them. They have demonstrated effec-tiveness in changing behaviors of individual health professionals, but not in redesigning clinical processes.

Pluses and minuses are inherent in the current status of clinical IT sys-tems. Medical informatics has facilitated the diffusion of computer technol-ogy within health professions by focusing on supporting existing processes. Automating these processes has limited the potential of the technology but facilitated its acceptance. The disadvantage is that the information architec-ture being developed to enable clinical process redesign might not be capa-ble of supporting it. Additional investment will have to be made to accom-plish this, revealing that much of the current investment has been wasted. Organizational leaders’ high expectations that the current investment would support or even produce clinical process change will not be met. Many CEOs have lacked sufficient understanding of IT to lead its application in process improvement. Many CIOs have viewed IT as technology applied to existing processes. Neither perspective is informed, resulting in a considerable waste of resources and time, increasing the frustration of all involved. The expecta-tions of executives and the promises of vendors that IT will initiate the trans-formation of business and clinical processes are clearly unrealistic.

Integrating the Clinical and Business Functions

Information technology has developed within healthcare organizations along parallel paths. There exists both a business and a clinical logic in the architec-ture, which serves as the underlying basis for developing IS. Their evolution

has resulted in a lack of coherence, common language, and architecture. The assumptions organizations make about process improvement for business and clinical functions are fundamentally different. Business IS view patients as number of visits, supplies consumed, professional services utilized, costs of procedures, and billing codes. Clinical IS are based on health conditions, medical diagnosis, results from diagnostic tests, and treatment regimens. The fundamental logic is inconsistent and contradictory between the decision needs and information structures of different business and clinical users. The incoherence within the information strategy of healthcare organizations is dif-ficult to overcome through interface systems. Chief information officers spend time and resources integrating information designed primarily to meet the needs of the disparate decision units. The focus of IT staff tends to be on the technical aspects of integrating IS instead of on restructuring processes.

The organizational commitment to clinical process redesign will change the nature of the organization in many ways. The clinical process will become more closely integrated operationally and strategically with the busi-ness function. Managers and clinicians will have real-time information on ical quality and patient satisfaction, guidelines to provide evidence-based clin-ical solutions, and cost and revenue implications of decisions. Business performance will be linked to clinical performance as a means of developing strategy and achieving both clinical quality and operational efficiency. Increas-ing pressures on healthcare organizations will require that they manage the business and clinical processes to achieve improved clinical outcomes with much greater efficiency. The integration of these functions within the organ-ization will require new skills in the leadership team and new management structures. Included in this redesign will be integrated IS that interrelate clin-ical and business performance of the organization and factors that affect per-formance.

The alignment of the business and clinical functions will also result from major new clinical technologies such as the human genome project. The inte-gration of genomic information with disease databases and effective clinical de-cision support systems will lead the health industry into third-wave technology and structure. Current clinical practice in hospitals and clinics and its relation-ship to computer technology is somewhat like flying a small airplane. The com-puter is an important aid and will reduce the risk of errors, but it is not essen-tial to takeoff and landing. In the genomic era, heath organizations will be in interplanetary flight, requiring computers to talk to computers. Humans will still be essential, but they will be supported by advanced IS. This will require new ways of thinking about work process and information support.

currently being installed. For organizations that do not pursue clinical and business process redesign, it will not make much difference what information architecture they choose.

The Constraining Potential of IT

Increasing Resistance to Change

The cost of installing advanced IS applied to old business and clinical processes or structural assumptions might be greater than simply the loss of investment. Healthcare organizations have been designed historically around independent functional structures, as depicted in Figure 1.1. Early IT applications to clinical support areas were on a functional or departmen-tal basis such as laboratory, nursing, pharmacy, and radiology. Each function had its own information system with its own purpose, logic, architecture, and data structure. The next generation of IT linked these disparate systems into common data architectures, databases, and integrated processes. This phase of development is typically built around the EMR and clinical support systems that draw on the clinical support departments. Developing an inte-grated system to support clinical services has proven to be a complex task because the purpose or use of data underpins the logic of the architecture. Changing the logic of the system into one that serves each functional area and the overall organizational purpose is difficult.

Although clinical IT systems are becoming integrated, they are designed to integrate processes that are functional in nature, consisting of lateral data models with interface structures. As discussed earlier, investment in IT sys-tems will not stimulate clinical process redesign. Such investments will likely further inhibit such change, as they tend to further institutionalize or freeze existing processes into place. Organizations that have made large IT invest-ments might have more difficulty undertaking process redesign because they will have to redesign both the clinical process and the data system to support it. This makes the process of change more difficult, as existing processes are more rigidly structured and there is a reluctance or inability to abandon the large investment in IT to start again. Instead of the CIO being a change ad-vocate, he she will tend to resist change.

A parallel IT development is occurring on the business side of the organiza-tion by automating existing purchasing, materials management, engineering, and other functions. There is greater probability of success undertaking busi-ness process redesign because it occurs on the busibusi-ness side of the enterprise and is under the control of management. The lagging development in this area is difficult to explain but probably results from a number of factors. First, healthcare organizations have not been forced to undertake business

Clinical IT systems

process redesign because of the ability to solve financial problems by securing more favorable reimbursement rates. Second, the structure of the health in-dustry as small, independent units has been a constraint on the power they bring to the table in restructuring the business value chain with suppliers (Davis 1991). Large integrated health systems have been more aggressive in business process redesign. Third, health managers in small institutions might lack the skills to lead an effective strategy to redesign business processes. Their training is more oriented to the administration of internal operations than to transform operations.

Evidence shows that business process redesign is progressing at a faster rate than clinical process redesign. This is understandable given the skepticism as to whether clinical process redesign is a legitimate area of responsibility of the organization and the fact that changing it will involve enlisting highly in-dependent professionals in the process. This will require a new leadership structure, with clinical leaders who understand the complex nature of organi-zational change and are committed to it. Managers might logically decide that they will focus on the business process and avoid clinical process redesign or delay it until business process design has been further developed. This strat-egy will inherently lead organizations into the same suboptimizing trap through investment in redesigning business processes and an information ar-chitecture that will then have to be unfrozen and redesigned to integrate with subsequent clinical process redesign. These will ultimately become integrated processes within the organization and cannot be considered independently in the short term.

Enlightened Organizational Change

The nature of change needed in healthcare organizations and the health sys-tem is easily described but very difficult to achieve. Toffler (1980) captures the essence in The Third Wave: in the technology and information age all as-sumptions about existing processes, structures, and even theories are no longer valid. Leaders must envision a totally new order based on the power of IT and the assumptions this technology makes on the existing order. It will not be possible to incrementally derive this new order on a function-by-func-tion or project-by-project basis; it will have to be envisioned by top leadership and instilled throughout all facets of the organization. The design of funda-mentally new processes and systems to support them will be carried out by transformational leaders.

The concept of transformational leadership is now popular in training pro-grams but is at best difficult to apply and generally misunderstood. It is a pow-erful concept, which assumes both vision and skills to implement solutions. Transformational leadership must start from the top and enlist others through-out the organization. It is difficult to envision a transformational leader as a de-partment director functioning within a structured and controlled environment.

Leadership training at the departmental level cannot be understood within the context of existing processes and systems without producing considerable frustration and ultimately failure.

The process of envisioning a new future should not be considered a fanciful diversion or intellectual exercise. The visioning function enables lead-ers to fix clearly for the organization how it can position itself to achieve ex-ceptional levels of performance in clinical quality, patient satisfaction, and ef-ficiency. In doing so, there must be sufficient commitment throughout the organization to the mission and a willingness to give up traditional beliefs and ways of doing things. The vision must enlist transformational leaders from throughout the organization to put in place new processes and structures for achieving the ideal. Information technology must be designed to enable this change and will in large part be the basis for the design. Leaders, however, must avoid the trap of thinking that the investment in IT will produce the change; it will not.

The design of the information architecture will be based on lateral clinical processes and data models, interconnected systems, knowledge-based systems, and integrated communications (Broadbent, Weill, and St. Clair 1999). The change process will have to be carefully planned and imple-mented to be successful, requiring considerable time, dedication, and re-sources. One strategy might be to implement process redesign in one clinical area and then extend the model and lessons learned to other clinical areas. Such a phased strategy, while incremental, allows adequate IT support for the process, early successes on which to build, pride on the part of those imple-menting systems, and institutional learning.

To achieve this outcome several pieces of the organization must be aligned. First, the governing board must fully understand and be firmly committed to supporting and investing in the transformation. The board will have to as-sume risks and transformation in its own right (Pointer and Orlikoff 1999). The leadership team will likely need technical expertise in clinical medicine, IT, financial management, and human resources management. All members of the team will have a good understanding of organizational strategy and change, IS, and clinical performance. The CIO must be able to both envision the future and lead the development of process redesign and structural change. The return on investment in IT will be measured by the value of the clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction, not merely by efficiencies resulting from automating back-office functions.

Information Skills for Health Systems Leaders

The skills necessary to participate in IT decisions include a basic understand-ing of IT and capacity, organizational structure and function, clinical outcomes

measurement, quality assessment, organizational leadership, and change. Fig-ure 1.2 provides a brief description of specific technical skills important to lead-ing change in healthcare organizations. The integration of the four technolo-gies shown in the figure provides the potential for generating real value.

Without an appreciation of basic technical aspects of IT, executives can-not envision what is possible. Without organizational skills, the technology cannot be applied.

In addition to general skills identified in Figure 1.2, a need exists for in-volvement of individuals with a mastery of specialty skills including informat-ics, medicine, nursing, finance, human resources, and management. These skills will not be contained within a single person, but rather will come from a team of organizational leaders. Each member of the top executive team will bring his or her own technical expertise but must also bring a basic knowledge of IT and its use in transforming organizations. The CIO is in a key position to lead this transformation. The CIO’s organizational and management skills might be as important as any technical skills in this case.

In addition to specific and shared technical skills, the top executive team must have accomplished leadership skills (see Figure 1.2). They must be able to transcend their own professional and technical areas to understand the com-plexities of the organization and communicate effectively using expert inter-personal skills. Their work will be characterized by vision, developing concep-tual models, spanning boundaries, communicating, negotiating, compromising, and risk taking (Kanter 1989). Individuals selected for top ex-ecutive positions should, first and foremost, demonstrate a high level of orga-nizational skills. High levels of technical informatics skills are not enough and, if combined with the desire to control and exert power, will be destructive.

Summary

This chapter explores the role of IT in transforming work processes in health organizations. Historically, IT has been oriented more toward automating tra-ditional business and clinical processes than transforming them. These applica-tions view IT primarily as a technical activity, and the staffing of IT depart-ments has reflected this orientation. Although complex in itself, applications to automate traditional business and clinical processes are relatively simple com-pared to transforming these processes.

finding that the integration of processes requires profound organizational change, including structures, processes, behaviors, and, to some degree, cul-ture. These changes are transformational in nature because they do not evolve from old processes but require new conceptual models of organization and work processes.

The transformation of clinical and business processes will require the application of advanced IT, although IT alone will not produce it. Change in the operations and strategies of organizations using advanced IT will require a leadership team with a common basic set of skills and appreciation of or-ganization design and change, IT clinical processes and outcomes, and lead-ership, as well as advanced skills in these areas by members of the top leader-ship team. If health systems apply the lessons learned in other service organizations, their potential reward will be achieving exceptional levels of clinical quality and business efficiency. The remaining chapters in this book explore in more detail the complexity and rewards of this undertaking.

Questions for Discussion

1. Give examples of how IT has affected business operations in industries such as banking and finance, transportation, and mass communication. 2. Why have healthcare organizations lagged behind other industries in

the application of advanced IT to transform work processes?

3. Discuss the relationship between investment in IT and the use of this technology to transform business and clinical processes.