Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ijme20

Journal of Medical Economics

ISSN: 1369-6998 (Print) 1941-837X (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ijme20

Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran etexilate for

stroke prevention in non-valvular atrial fibrillation.

Applying RE-LY to clinical practice in Denmark

Lars K Langkilde, Mikael Bergholdt Asmussen & Mikkel Overgaard

To cite this article: Lars K Langkilde, Mikael Bergholdt Asmussen & Mikkel Overgaard (2012) Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran etexilate for stroke prevention in non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Applying RE-LY to clinical practice in Denmark, Journal of Medical Economics, 15:4, 695-703

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3111/13696998.2012.673525

Accepted author version posted online: 07 Mar 2012.

Published online: 22 Mar 2012.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 389

View related articles

Copyright

© 20

12

Inf

orma UK Li

mited

Not for

Sale or

Comm

erc

ial Dist

ribution

Un

auth

or

ize

d u

se

proh

ibi

te

d. Au

tho

rise

d u

se

rs

c

an

down

loa

d,

di

sp

lay, v

iew an

d pri

nt

a sing

le c

op

y for per

so

nal

u

se

Original article

Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran etexilate

for stroke prevention in non-valvular atrial

fibrillation. Applying RE-LY to clinical

practice in Denmark

Lars K Langkilde

Wickstrøm & Langkilde ApS, Vejle, Denmark

Mikael Bergholdt Asmussen

Mikkel Overgaard

Boehringer Ingelheim Denmark, Copenhagen, Denmark

Address for correspondence:

Lars K Langkilde, Wickstrøm & Langkilde ApS, Hjulmagervej 4A Vejle, DK-7100, Denmark. Tel.:þ4541111183; Fax: +45 3514 1110; [email protected]

Key words:

Anti-coagulation – Dabigatran etexilate – Warfarin – Atrial fibrillation – Cost-effectiveness – Denmark

Accepted: 5 March 2012; published online: 22 March 2012

Citation:J Med Econ 2012; 15:695–703

Abstract

Objective:

To estimate the economic implications of introducing dabigatran etexilate (‘dabigatran’) for anti-coagulation therapy in Danish patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation based on results of the RE-LY trial.

Methods:

The lifetime cost and outcomes of dabigatran and warfarin were estimated using a previously published cost-effectiveness model. The model utilizes the data from the RE-LY study to estimate the costs and outcomes of stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Cost estimates were based on official Danish tariffs and prices, and published literature on the cost of stroke. In the base-case analysis a conservative approach was adopted applying tariffs from the lowest range for the cost of International Normalized Ratio (INR) monitoring associated with warfarin. The effectiveness measure of the analysis was quality-adjusted life-years (QALY).

Results:

The model estimated that the mean cost per patient for the remaining life-time isE16,886 treated with warfarin andE18,752 treated with dabigatran. This was associated with mean QALYs per patient of 8.32 with warfarin and 8.59 with dabigatran. The resulting incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of

E7000 per QALY gained is regarded as cost-effective by Danish standards. This conclusion was seen to be robust to realistic variations in input parameters, including adjustment for the RE-LY centres achieving the best INR monitoring quality. Threshold analysis revealed that dabigatran would be cost-saving in settings where the cost of warfarin monitoring exceedsE744 per year.

Limitations:

The analysis does not include all aspects of Danish clinical practice anti-coagulation that will influence cost-effectiveness of dabigatran, e.g., this study did not attempt to model quality of anticoagulation monitoring and under-utilization in clinical practice.

Conclusions:

Based on the outcomes observed in the RE-LY trial, dabigatran represents a cost-effective alternative to warfarin in Denmark for all patients with atrial fibrillation within the licensed indication of dabigatran.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia, which increases morbidity and mortality principally due to the resultant 5-fold increased risk of stroke compared to patients without AF. Persons above 40 years of age have a

25% lifetime risk of developing AF1. Based on interna-tional literature1–3, Brandes4 estimated that more than 50,000 Danish patients suffer from AF, with prevalence expected to treble by the year 2050.

Anticoagulation is recommended for AF patients with risk factors for thromboembolic events5. The use of antic-oagulation with vitamin K antagonists has evolved over time. Two decades ago it was generally limited to AF patients with rheumatic heart disease and prosthetic heart valves6. With growing evidence from randomized controlled trials an increasing number of AF patients are recommended for anticoagulation treatment5.

The historical standard for anticoagulation treatment in Denmark has been the vitamin K antagonist warfarin. Warfarin reduces the risk of stroke by60% compared to placebo and 30–40% compared to treatment with aspirin7. Warfarin can be cumbersome to use because of the multi-ple drug–drug and drug–food interactions, and the signif-icant intra- and inter-patient variability in terms of therapeutic response. Achieving a therapeutic dose in clinical practice requires regular monitoring of the International Normalized Ratio (INR) and dose adjust-ment. The quality of INR monitoring has been shown to vary between countries8and is related to how anticoagula-tion management is organized9, with implications for real-life effectiveness10. However, in Denmark, valid data on warfarin management performance is not available. The majority of Danish warfarin patients are managed by their general practitioner.

Friberget al.11reported that only 36% of patients hos-pitalized with a diagnosis of AF in Denmark claimed a prescription of vitamin-K antagonists (i.e., warfarin) within 3 months of discharge. Furthermore, a recent Danish study of secondary prophylaxis showed that among patients older than 80 years only25% of patients with atrial fibrillation and no contraindications for anti-coagulant therapy at the time of the initial hospital admis-sion were treated with oral anticoagulation 1 year after the initial ischemic stroke12.

Dabigatran etexilate (‘dabigatran’) is a new oral direct thrombin inhibitor which provides a predictable anticoag-ulant effect with no need for anticoagulation monitoring. In 2008, dabigatran was approved in Europe for primary prevention of venous thromboembolic events in adult patients who have undergone elective total hip or knee replacement surgery. In August 2011 dabigatran was approved in Denmark for stroke prevention for patients with non-valvular AF with at least one risk factor.

In the Randomized Evaluation of Long-term

Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY) trial (n¼18,113), the efficacy and safety of dabigatran was compared with war-farin in patients with AF with risk factors for stroke13,14. Two doses of dabigatran were tested and dabigatran 150 mg twice daily was associated with a significant lower rate of stroke/systemic embolism and a comparable

rate of major haemorrhage compared to warfarin, whereas dabigatran 110 mg twice daily was associated with a com-parable rate of stroke and systemic embolism and a signif-icant lower rate of major haemorrhage compared to warfarin. Both doses significantly reduced the rate of intra-cranial and life-threatening bleeding compared to warfarin14.

With an increasing prevalence of AF and a lower threshold for initiating anticoagulation therapy it is rele-vant to consider which treatment option represents the best value-for-money. The purpose of this analysis is to estimate the long-term cost-effectiveness of stroke preven-tion in patients with AF using dabigatran as an alternative to warfarin in a Danish setting.

Methods

Model of clinical events

We adapted an economic model of long-term (remaining life-time) cost and outcomes based on the RE-LY trial published by Sorensen et al.15,16.The model has Markov properties, i.e., it is assumed that any patient’s health can be represented as a finite number of health states. Transitions between states can occur once every 3 months with transition probabilities conditional on the present health state, baseline characteristics of the patient, and progression of time. The health states represent ische-mic stroke history, degree of disability following stroke (independent, moderately disabled, or dependent), current treatment (first line, primary prophylaxis using warfarin/ dabigatran treatment, second line prophylaxis using aspi-rin, or no treatment), and death. The model estimates the distribution of patients on health states from entry into the model and until all patients are dead, i.e., the time perspective is remaining life-time. Calculations were per-formed in Microsoft Excel 2007.

Clinical events modelled include ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack, systemic embolism, acute myo-cardial infarction, intracranial haemorrhage and haemor-rhagic stroke, other major haemorrhages, and minor bleeds.

The publication by Sorensenet al.16analyses the long-term cost and outcomes from a Canadian perspective and was adapted further to the Danish healthcare setting. The Canadian cost-effectiveness model is suitable for this adap-tation because its main analysis was based on the RE-LY data and applies the sequential dosing strategy of dabiga-tran that is common between the approved European and Canadian labels. The posology reflected in the cost-effectiveness model initiates patients under the age of 80 years at dabigatran 150 mg twice daily followed by 110 mg twice daily at the age of 80 years and over.

Journal of Medical Economics Volume 15, Number 4 August 2012

Risk of events

In our adaptation we used the baseline analysis of the Canadian adaptation which is an extrapolation of out-comes in the RE-LY trial to long-term (lifetime) outout-comes and cost. Below we will only provide a short summary of the modelling approach. For full details please consult Sorensenet al.16.

Risk of clinical events for patients on warfarin and dabigatran were based on observed event rates in the RE-LY trial. Separate risk estimates for all modelled clin-ical events were estimated for the sub-group of patients respectively younger than or at least 80 years of age at baseline16.

Risk of ischaemic stroke was estimated separately for each sub-group of patients based on the CHADS2— scoring of risk factors17 at baseline. In the model the CHADS2is reassessed every cycle to reflect changes in the risk factors as a result of predicted clinical events during the previous 3-month cycle.

Treatment and treatment effects

Patients entering the economic model are assumed to receive either warfarin (target INR 2–3) or dabigatran. Patients are assumed to discontinue from any of the treat-ments in the case of an intracranial haemorrhage (ICH). Furthermore, we assume that 50% of other major haemor-rhages lead to permanent discontinuation of anti-thrombotic treatment. These patients are assumed to be at risk of clinical events at rates that reflect those of pla-cebo-treated patients in published clinical trials, and an increased mortality risk depending on the level of disability16. Furthermore, treatment switches (from warfa-rin or dabigatran to aspiwarfa-rin) can occur in the model for other reasons. In this case patients are assumed to experi-ence risks of clinical events and costs as if treated with aspirin. Rates of discontinuation for warfarin and dabiga-tran were estimated using data from RE-LY.

For warfarin and dabigatran the events rates were esti-mated from RE-LY. For aspirin (modelled as a second line treatment option) and no treatment (used for modelling the clinical events for patients who have discontinued all anti-thrombotic treatment following a major haemorrha-gic event) event rates are based on an adaptation of a recently published meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials involving warfarin, aspirin, and/or placebo18.

Estimation of health outcomes

Long-term health outcomes were estimated as number of clinical events, life expectancy (life-years), and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs).

QALYs were estimated by weighting 3-month survival by a utility weight for the health state during that cycle. If a

clinical event occurred during a cycle, a temporary utility decrement was subtracted from the health state utility. Utility weights relevant to AF in a Danish population are not available; hence we used the same values as applied in Sorensenet al.16.

Adaptation of clinical event model

Danish age- and gender-specific death rates from national population statistics19 were applied. In order not to double-count causes of deaths already accounted for in the model as event-related mortality, only death from other causes than stroke, bleeding, systemic emboli, and acute myocardial infarction was included in the calcula-tion of death rates.

Furthermore, since the efficacy and safety of warfarin are related to the achieved quality of INR monitoring, a sensitivity analysis was planned allowing the level of time-in-therapeutic range (TTR) to deviate from that of the warfarin treated patients in the RE-LY trial. The costs and outcomes of dabigatran and warfarin were compared using results from a post-hoc analysis of RE-LY based on centre average TTR20. Relative risk ratios were reported by quartile of patients according to the mean TTR achieved by the trial centre that the patient attended during RE-LY. The patients from the lowest quartile represent models of care achieving a low level of TTR (centres with an average TTR of less than 57.1%) and the highest quartile represent models of care with a high level of TTR for INR monitor-ing (centres with average TTR at least 72.6% or above). The relative risk ratios reported20for ischaemic stroke and systemic embolism, intra-cranial bleeding, and major bleedings for these two extreme quartiles were applied as sensitivity analyses.

Cost of medical products

Costs of medicinal products are based on the current phar-macist sales prices including dispensing fees but excluding VAT21. For warfarin a daily cost of treatment based on a 5 mg daily dosage is assumed22.

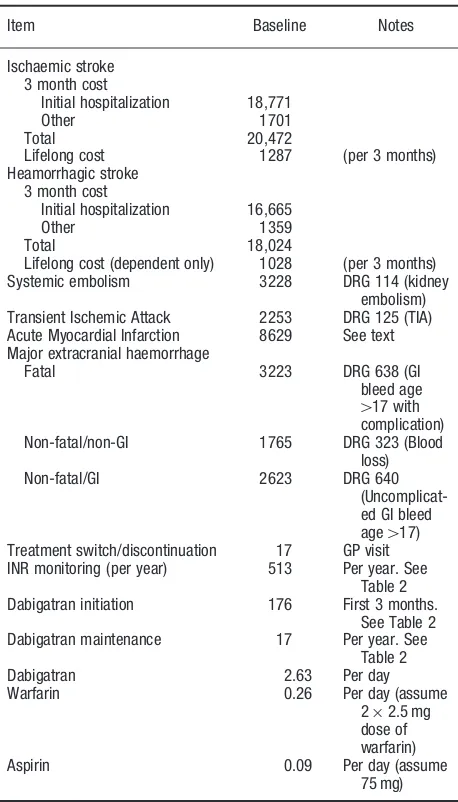

Estimation of cost

The direct costs associated with anti-thrombotic treat-ment and clinical events were estimated using primarily national tariffs where available23,24 and data from other publicly-available sources otherwise. Transferrals such as pensions, work disability compensation, and value added tax (VAT) were excluded. Table 1 provides an over-view of the included cost components in the model. In the following all cost are reported in euro (E) based on the 2011 annual average currency rate (100 Danish Kroner¼13.42E).

Cost of stroke

Cost of stroke is a key parameter in the costing of clinical events. Tariffs are available for the initial hospitalization in the Danish Disease Related Groups (DRG) classifica-tion of hospitalizaclassifica-tions. However, it was not possible to identify up-to-date Danish studies of resource utilization associated with stroke (re-hospitalization, rehabilitation, and social costs) following the initial hospitalization.

Porsdal and Boysen25performed a comprehensive esti-mation of first year resource utilization following ischae-mic and haemorrhagic stroke based on cost applicable to 1995. The hospital cost during the initial hospitalization constituted 63.4% of the total first year direct medical and social cost in patients admitted with ischaemic stroke and 59.4% of first year cost in haemorrhagic stroke. The initial hospitalization cost for ischaemic stroke and ICH in the model was based on Porsdal and Boysen25.

The first year follow-up cost from Porsdal and Boysen25 could not be used directly because it included cost related to secondary strokes occurring within the first year. Since secondary stroke is estimated and assigned a cost in our clinical model this would imply double counting cost of secondary strokes. From a Swedish study on cost of stroke with 4 years follow-up26it was possible to estimate that 11% of first year follow-up cost was related to secondary stroke. The Danish estimate of first year follow-up cost was reduced by this amount.

Furthermore, the long-term cost of stroke was esti-mated. The Swedish study reported that social cost and follow-up cost are highest in the first year following the initial stroke event and fairly stable the second through fourth year. The annual cost years 2–4 was24% lower than first year follow-up cost. This relative reduction in cost (based on the Swedish observation) was applied to our estimate of the Danish first year follow-up cost. In order to use the estimated long-term follow-up cost conservatively we only applied it to patients with moderate or severe disability after the initial stroke event. Estimates of stroke cost were inflated to 2011 values using the consumer price index27.

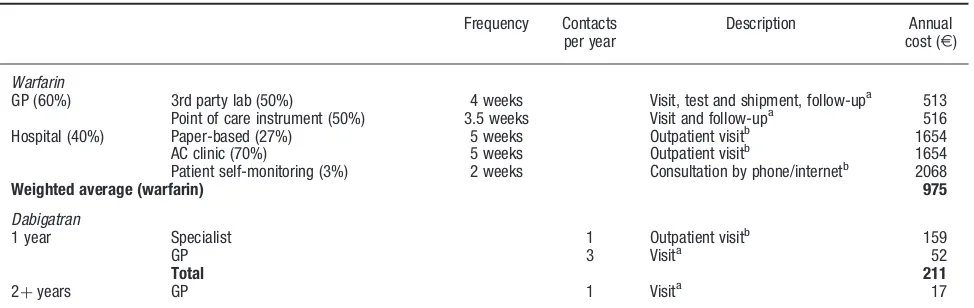

Cost of patient management

INR monitoring is organized in a number of different ways in Denmark28. For the base-case analysis, the cost of INR monitoring was estimated based on the most common and least costly set-up where INR monitoring is managed by general practitioners. Based on publicly available tariffs and assumed annual number of contacts, the base-case cost for INR monitoring was estimated toE513. In sensi-tivity analyses, the impact of different scenarios for INR monitoring costs was analysed. In one scenario—reflecting the split between primary care and hospital organized INR monitoring in Denmark—the cost of INR monitoring was estimated as a weighted average of cost for the three most frequent models of care in Denmark. For each model of care the annual number of contacts to the provider and the proportion of the patient population being monitored were assessed. Cost per contact was estimated using publicly available tariffs. The resulting annual cost per patient is

E975 per year (weighted average based on estimated patient distribution by models of care, see Table 2). The publicly-available tariffs especially for hospital contacts have been shown to deviate from variable cost of monitor-ing, i.e., cost estimated from the pure work input and mate-rials used during one contact28. In another scenario only variable cost per contact were taken into consideration. Variable costs are—as also stated by Holmet al.28—only a relevant measure in short-term analyses, since they do not take into account the overhead cost associated with run-ning the clinic or the alternative use of clinic space for Table 1. List of unit cost estimates applied in the model. In Euro (E).

Item Baseline Notes

Lifelong cost 1287 (per 3 months) Heamorrhagic stroke

3 month cost

Initial hospitalization 16,665

Other 1359

Total 18,024

Lifelong cost (dependent only) 1028 (per 3 months) Systemic embolism 3228 DRG 114 (kidney

embolism) Transient Ischemic Attack 2253 DRG 125 (TIA) Acute Myocardial Infarction 8629 See text Major extracranial haemorrhage

Fatal 3223 DRG 638 (GI bleed age

417 with

complication) Non-fatal/non-GI 1765 DRG 323 (Blood

loss) Non-fatal/GI 2623 DRG 640

(Uncomplicat-ed GI ble(Uncomplicat-ed age417)

Treatment switch/discontinuation 17 GP visit INR monitoring (per year) 513 Per year. See

Table 2 Dabigatran initiation 176 First 3 months.

See Table 2 Dabigatran maintenance 17 Per year. See

Table 2 Dabigatran 2.63 Per day Warfarin 0.26 Per day (assume

22.5 mg dose of warfarin) Aspirin 0.09 Per day (assume

75 mg) Journal of Medical Economics Volume 15, Number 4 August 2012

other purposes. Variable cost was estimated based on expe-rience from a hospital-based anticoagulation clinic using computer-assisted dosing (calculations not shown). The resulting variable cost of monitoring was estimated to

E418 per year.

There is no need for anticoagulation monitoring or dose adjustment with dabigatran. However, a temporary higher cost for initiation of dabigatran and a permanent cost of dabigatran management were included. It was assumed that all patients will be seen by a cardiologist (outpatient visit) at initiation of dabigatran treatment and by a GP three times during the first year and once yearly thereafter specifically related to dabigatran. In reality, dabigatran-related issues are likely to be part of the general patient management and dealt with in the course of other AF related visits. However, in the model these are considered additional to any other visits the patients may have as a consequence of their health state. Renal function testing will also occur at those visits, according to the Danish label.

Cost of bleeding events

Cost of ICH was based on published cost of stroke esti-mates25 as outlined above. Major bleeding events other than intracranial haemorrhage were estimated using DRG tariffs. Costs of fatal and non-fatal gastrointestinal (GI) bleedings were estimated using the tariff for GI bleed-ings, respectively, with and without complications, while costs for non-GI major bleedings were estimated using the tariff for inpatient treatment of blood loss. Minor bleedings were not applied any cost in the base-case analysis. In sensitivity analyses a cost range of20% of the baseline estimates (both intracranial and other major bleedings)

were tested. We applied the higher bleeding cost to both treatments and—in a separate sensitivity analysis—only to dabigatran-treated patients and for this analysis we also applied the cost of a GP visit for minor bleedings in dabi-gatran-treated patients. The asymmetric analysis of bleed-ing cost was applied to test whether an increase in resource utilization associated with the new medicine would be crit-ical for the conclusion.

Cost of acute myocardial infarction (AMI)

Cost of AMI is based on observed use of revasculariza-tion and imaging procedures in 24,952 Danish patients with incident ACS29. Applying 2011 tariffs to the case-mix reported leads to an estimated cost per event of

E8629.

Discounting

All future costs and outcomes (QALYs) were discounted in accordance with standards set by the Danish Ministry of Health30 at an annual rate of 2%, with 0% and 4% dis-counting tested in sensitivity analyses.

Patient cohort

We estimated outcomes and cost for a modelled cohort of 10,000 patients with a similar risk profile (described by CHADS2) to the patients aged 80 or below included in the RE-LY trial. The average age was 69 years and 65% of patients were male.

Table 2. Calculation of annual patient management cost on dabigatran and warfarin (Euro).

Frequency Contacts per year

Description Annual cost (E)

Warfarin

GP (60%) 3rd party lab (50%) 4 weeks Visit, test and shipment, follow-upa 513 Point of care instrument (50%) 3.5 weeks Visit and follow-upa 516

Hospital (40%) Paper-based (27%) 5 weeks Outpatient visitb 1654 AC clinic (70%) 5 weeks Outpatient visitb 1654 Patient self-monitoring (3%) 2 weeks Consultation by phone/internetb 2068

Weighted average (warfarin) 975

Dabigatran

1 year Specialist 1 Outpatient visitb 159

GP 3 Visita 52

Total 211

2þyears GP 1 Visita 17

AC, Anti-coagulation; GP, general practitioner. aUnit cost (

E): visit 17.38, blood test and shipment 8.94, INR (PoC) 14.63, phone consultation 3.41, mail follow-up 5.47. Assumes 50% of follow-up is done face-to-face and 50% via phone/mail.

bUnit cost (

E): Outpatient visit 159.05, phone contact 79.52.

Results

Cost and outcomes

Table 3 reports the estimation of long-term cost and out-comes for the baseline analysis. The estimated total cost per patient for the remaining life-time is E16,886 for patients treated with warfarin andE18,752 for patients

treated with dabigatran. The additional cost associated with dabigatran (E1866) is mainly driven by the addi-tional cost of medication. The estimated QALYs per patient are 8.32 for warfarin and 8.59 for dabigatran. The expected survival (discounted by 2% per annum) is 11.34 and 11.61 years, for warfarin and dabigatran, respectively. The resultant incremental cost per QALY gained is

E6950. There is no officially accepted threshold for incre-mental cost per QALY in Denmark. However, an ICER below 30,000E/QALY is regarded as cost-effective, and, hence, dabigatran is considerably below this threshold compared to warfarin in the baseline analysis.

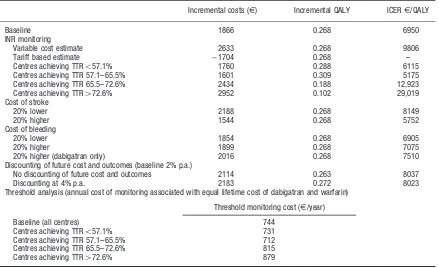

Sensitivity analysis

Table 4 reports the main findings from the sensitivity anal-ysis. Two different scenarios for INR monitoring cost and/ or a high quality of INR monitoring were analysed.

If INR monitoring costs were based on a weighted aver-age of the three most frequent models of care in Denmark, the assigned cost of INR monitoring wasE975. In this real-life scenario, dabigatran was shown to be dominant (i.e., lower cost and better outcome compared to warfarin). If INR monitoring is assigned only the variable cost, the incremental cost is E2633 per patient (compared to

E1866 in the base-case). This leads to an incremental cost per QALY gained ofE9806. Given these results dabi-gatran would be regarded as cost-effective compared to

Table 4. Univariate sensitivity analyses. Net present value of incremental cost and outcomes (dabigatran minus warfarin).

Incremental costs (E) Incremental QALY ICERE/QALY

Baseline 1866 0.268 6950

INR monitoring

Variable cost estimate 2633 0.268 9806

Tariff based estimate 1704 0.268 –

Centres achieving TTR557.1% 1760 0.288 6115

Centres achieving TTR 57.1–65.5% 1601 0.309 5175 Centres achieving TTR 65.5–72.6% 2434 0.188 12,923 Centres achieving TTR472.6% 2952 0.102 29,019

Cost of stroke

20% lower 2188 0.268 8149

20% higher 1544 0.268 5752

Cost of bleeding

20% lower 1854 0.268 6905

20% higher 1899 0.268 7075

20% higher (dabigatran only) 2016 0.268 7510 Discounting of future cost and outcomes (baseline 2% p.a.)

No discounting of future cost and outcomes 2114 0.263 8037

Discounting at 4% p.a. 2183 0.272 8023

Threshold analysis (annual cost of monitoring associated with equal lifetime cost of dabigatran and warfarin)

Threshold monitoring cost (E/year)

Baseline (all centres) 744 Centres achieving TTR557.1% 731

Centres achieving TTR 57.1–65.5% 712 Centres achieving TTR 65.5–72.6% 815 Centres achieving TTR472.6% 879

p.a., per annum; QALY, Quality-adjusted life years; TTR, Time in therapeutic interval.

*Incremental cost per QALY gained (dabigatran compared to warfarin).

Table 3. Baseline cost and quality-adjusted life-years per patient (life-long projection) by treatment strategy. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (warfarin compared to dabigatran).

Sequentiala

Dabigatran use

Warfarin

Direct costs/Patient

Drug costs and Monitoring (E) 8232 4935 Event costs (E) 8787 9727 Follow-up costs (E) 1733 2224 Total (E) 18,752 16,886 Incremental costs (E) 1866

Benefits/Patient (discounted at 2% per annum)

Expected number of eventsb 0.47 0.55

Expected survival (years) 11.61 11.34

QALYs 8.59 8.32

Incremental QALY 0.27 ICER (Dabigatran vs warfarin)

Direct Costs (E) per QALY gained 6950

QALY, Quality adjusted life years; ICER, incremental cost effectiveness ratio. a

150 mg b.i.d. for age below 80 then 110 mg b.i.d. bStroke, systemic embolism, and intracranial haemorrhage.

Journal of Medical Economics Volume 15, Number 4 August 2012

warfarin by any reasonable method of applying the cost of

INR monitoring under base-case assumptions.

Furthermore, it was shown in the sensitivity analysis that if the annual cost of INR-monitoring exceedsE744, dabi-gatran would dominate warfarin.

Taken into consideration the achieved quality of INR monitoring based on the centre average TTR, the incre-mental cost per QALY range fromE6115 for the lowest level of quality (centres with an average TTR of less than 57.1%) toE29,019 for the highest level of quality (centres with average TTR at least 72.6% or above). Dabigatran would be regarded as cost-effective to warfarin, irrespective of average level of centre TTR.

The results were not sensitive to 20% changes in cost of stroke or bleeding. In the case of bleeding cost we applied a 20% higher cost only to the dabigatran arm. This resulted in an incremental cost per QALY ofE7510, which is still cost-effective compared to warfarin. The conclusion was also found to be insensitive to the rate of discounting of future cost and outcomes.

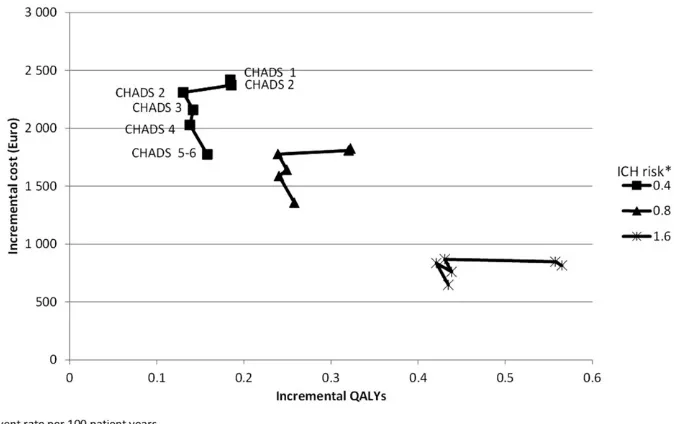

Figure 1 provides the results from sensitivity analysis with respect to various combinations of risks of intracra-nial haemorrhage and stroke (based on CHADS2score). Each cluster represents a level of ICH risk (from 0.4 events per 100 patient years to 1.6 events per 100 patient years) and each point represents a CHADS2score from 0–5/6. In RE-LY the risk of ischaemic stroke on warfarin treatment varied between 0.62 events per 100 patient years for patients with a CHADS2 score of 0 at baseline to 2.77 events per 100 patient years for patients with a score of 5–6 at baseline16. The risk of ICH has a larger impact on

both incremental cost and incremental outcomes than the risk of thromboembolic events. In general, higher levels of risk are associated with lower incremental cost of dabiga-tran treatment and larger patient benefits (measured in QALY gained) compared to warfarin. In all of the analysis in Figure 1 the ICER is belowE18,000 per QALY gained and hence dabigatran remains cost-effective compared to warfarin.

Discussion

This analysis evaluated the cost-effectiveness of dabiga-tran vs warfarin for patients with atrial fibrillation in a Danish healthcare setting based on the results from the RE-LY trial. In the base-case analysis dabigatran was shown to be a cost-effective strategy for patients with atrial fibrillation and the sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the base-case finding. The applied cost-effectiveness model is—as with any extrapolation— limited by the amount of evidence available. Hence, the following limitations of this analysis should be mentioned. The driving factor behind the costs and outcomes are the risk levels for clinical events in the model. These are primarily based on observed risk levels in the RE-LY trial and the generalizability of the trial to the Danish setting in terms of selection of patients, healthcare providers, and patient management should be examined. This cost-effectiveness does not address this real-life scenario with patient exclusion however; Sorensenet al.16showed that the cost-effectiveness ratio will become even more Figure 1. Incremental cost and quality-adjusted life-years at varying level of thrombo-embologic and intra-cranial haemorrhage risk.

Note: Each cluster represents a level of ICH risk from 0.4 to 1.6 events per 100 patient years. Each point represents a level of CHADS2from 0 (0.62

events/100 patient years) to 5–6 (2.77 event/100 patient years).

favourable for dabigatran in case a real-life scenario is applied in addition to the applied RE-LY scenario.

Furthermore, we compare a new treatment option with an established one. A number of assumptions were made to estimate the annual dabigatran treatment cost, e.g., the number of healthcare contacts, management of dabiga-tran-related bleedings, and treatment adherence. Prospective data from a real-life setting will be needed to provide more accurate estimates of dabigatran manage-ment and related cost.

Another aspect which is not reflected in this cost-effec-tiveness analysis is the substantial lack of treatment for AF-patients who according to risk profile are recom-mended to receive anticoagulation therapy. Friberg et al.11 documented—based on a Danish database study (n¼68,546)—that only 36% of the patients hospitalized with a diagnosis of AF claimed a prescription of vitamin-K antagonists (i.e., warfarin) within 3 months from dis-charge. The reasons for this lack of treatment may be related to the fact that treatment with warfarin is consid-ered as cumbersome due to the interactions with other drugs and food and the frequent need for INR monitoring to ensure an acceptable level of treatment quality. Treatment with dabigatran does not have any drug–food interactions, has very limited drug–drug interactions, and does not require anticoagulation monitoring. An analysis of the use of dabigatran in AF patients eligible for antic-oagulation treatment who are currently under-treated indicated that this would be a cost-effective strategy16; however, this should be investigated further in the Danish setting.

An indicator for the quality of the warfarin treatment is the time in therapeutic range (TTR). As a part of the sensitivity analysis, a hypothetical situation with a TTR similar to the highest quartile of the centre-based TTR sub-group analysis of RE-LY for warfarin was compared with dabigatran treatment. Also in this situation, dabiga-tran was demonstrated to be a cost-effective alternative to warfarin. In Denmark, the perception is that the TTR for warfarin treatment is relatively high compared to the TTR for other countries, as also reported for the Danish centres participating in RE-LY20. However, very little is known about the actual achieved TTR for the majority of Danish patients who are managed outside specialized anticoagulation clinics. The introduction of dabigatran holds the promise of a less diverse level of anticoagulation treatment among different patient groups and most impor-tantly a predictable high level of anticoagulation treatment.

In the base-case analysis a conservative approach to costing was applied. In regards to INR monitoring an esti-mate from the low range of tariffs that are paid to health-care providers for managing patients was applied. This is done in order to be conservative in evaluating dabigatran compared to the established treatment option. For the

Danish healthcare budget holders, however, the actual— higher—tariffs are more relevant. Sensitivity analysis showed that when the actual tariffs are used, dabigatran dominates warfarin, i.e., resulting in lower long-term cost and better long-term outcomes. Also for the cost of stroke a conservative estimate was applied. The Danish National Board of Health refers to an estimate of the total first year cost of stroke of E21,500 at 2001 cost levels31. Furthermore, it has been shown that strokes related to atrial fibrillation are more costly compared with strokes not related to atrial fibrilation32,33.

Conclusions

Dabigatran is a new anticoagulant treatment for patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Based on findings from an economic model based on the results from RE-LY, dabigatran was found to be cost-effective from a Danish healthcare perspective when compared to warfarin.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The project was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim, Denmark.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Lars K. Langkilde was a paid consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim for this project. Mikael Bergholdt Asmussen and Mikkel Overgaard are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim Denmark.

Acknowledgements

Sonja V. Sorensen and Anuraag R. Kansal from United BioSource Corporation developed the initial model15,16 and kindly provided us access to the model and a detailed description of methods and assumptions. Furthermore, we thank Steen Husted, MD PhD, Regional Hospital West Jutland, Jens Flensted Lassen, MD PhD, Aarhus University Hospital, and Anna-Marie Mu¨nster, MD PhD, Aalborg Hospital, for acting as advisors on clinical practice in anti-thrombotic management in Denmark and giving valuable input on the analysis plan and interpretation of results.

References

1. Lloyd-Jones DM, Wang TJ, Leip EP, et al. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2004;110:1042–6 2. Heeringa J, van der Kuip DAM, Hofman A, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and

lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation: The Rotterdam Study. Eur Heart J 2006; 27:946-53

3. Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, et al. Secular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections of future prevalence. Circulation 2006;114:119-25 4. Institute For Rational Pharmacotherapy. Behandling af atrieflimren. Rationel

Pharmakoterapi Juni 2008 No 6 Journal of Medical Economics Volume 15, Number 4 August 2012

5. The Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2010;31:2369-429

6. Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke 1991;22:983-8

7. Hart RG, Benavente O, McBride R, et al. Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:492-501

8. Pengo V, Pegoraro C, Cucchini U, et al. Worldwide management of oral anticoagulant therapy: the ISAM study. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2006; 21:73-7

9. Ansell J, Hollowell J, Pengo V, et al. Descriptive analysis of the process and quality of oral anticoagulation management in real-life practice in patients with chronic non-valvular atrial fibrillation: the international study of antic-oagulation management (ISAM). J Thromb Thrombolysis 2007;23:83-91 10. Amouyel P, Mismetti P, Langkilde LK, et al. INR variability in atrial fibrillation: a

risk model for cerebrovascular events. Eur J Intern Med 2009;20:63-9 11. Friberg J, Gislason GH, Gadsbøll N, et al. Temporal trends in the prescription

of vitamin K antagonists in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Intern Med 2006;259:173-8

12. Palnum KH, Mehnert F, Andersen G, et al. Medical Prophylaxis following hospitalization for Ischemic Stroke: age- and sex-related differences and relation to mortality. Cerebrovasc Dis 2010;30:556-66

13. Ezekowitz MD, Connolly S, Parekh A, et al. Rationale and design of RE-LY: randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy, warfarin, com-pared with dabigatran. Am Heart J 2009;157:805-10

14. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1139-51 15. Sorensen SV, Dewilde S, Singer DE, et al. Cost-effectiveness of warfarin: trial

versus ‘‘real-world’’ stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J 2009;157:1064-73

16. Sorensen SV, Kansal AR, Connolly S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran etexilate for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in atrial fibrillation: a Canadian payer perspective. Thromb Haemost 2011; 105:908-19

17. Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, et al. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA 2001; 285:2864-70

18. Roskell NS, Lip GY, Noack H, et al. Treatments for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a network meta-analysis and indirect comparisons versus dabiga-tran etexilate. Thromb Haemost 2010;104:1106-15

19. Statistics Denmark Table HISB8. Life table (2 years tables) by age, sex and life table (1981:1982-2009:2010). Copenhagen: Statistics Denmark. 2010 http://www.statistikbanken.dk. Accessed December 13, 2010

20. Wallentin L, Yusuf S, Ezekowitz MD, et al, on behalf of the RE-LY investigators. Efficacy and safety of dabigatran compared with warfarin at different levels of international normalised ratio control for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: an analysis of the RE-LY trial. Lancet 2010; 6736:61194-4

21. Danish Medicines Agency. Medicinpriser. Copenhagen: Danish Medical Agency, 2011 http://www.medicinpriser.dk. Accessed March 15, 2011 22. Danish Society of Cardiology. Antitrombotisk behandling ved kardiovaskulære

sygdomme. Trombokardiologi. DCS Guidelines. Copenhagen: Danish Society of Cardiology, 2007

23. Ministry of Health. Takstsystem 2011 – vejledning. Copenhagen: Ministry of Health, 2011

24. Danish Medical Association. Honorartabel 01-04-2011. Copenhagen: Danish Medical Association, 2011

25. Porsdal V, Boysen G. Direct costs during the first year after intracerebral hemorrhage. Eur J Neurol 1999;6:449-54

26. Ghatnekar O, Persson U, Glader EL, et al. Cost of stroke in Sweden: an incidence estimate. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2004;20:375-80 27. Statistics Denmark. Table PRIS8. Consumer price index, annual average

(1900=100) by type (1900-2010). Copenhagen: Statistics Denmark, 2010 http://www.statistikbanken.dk. Accessed December 10, 2010

28. Holm T, Lassen JF, Genefke J, et al. Cross-sectorial cooperation between general practice and hospital – shared care elucidated using anticoagulant therapy as an example. Medicinsk Teknologivurdering – puljeprojekter. Copenhagen: National Board of Health, 2006

29. Hvelplund A, Galatius S, Madsen M, et al. Women with acute coronary syn-drome are less invasively examined and subsequently less treated than men. Eur Heart J 2010;31:684-90

30. Committee on Health Promotion and Disease. Vi kan leve længere og sundere. Forebyggelseskommisionens anbefalinger til en styrket forbyggende indsats. Report. Copenhagen: Ministry of Health, Committee on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, 2009

31. National Board on Health. Referenceprogram for behandling af patienter med apopleksi. Copenhagen: National Board On Health, 2005

32. Ghatnekar O, Glader EL. The effect of atrial fibrillation on stroke-related inpatient costs in Sweden: a 3-year analysis of registry incidence data from 2001. Value Health 2008;11:862-8

33. Bru¨ggenju¨rgen B, Rossnagel K, Roll S, et al. The impact of atrial fibrillation on the cost of stroke: the Berlin acute stroke study. Value Health 2007;10:137-4