A STUDY ON THE LEXICAL RICHNESS IN THE WRITTEN

WORK OF THIRD YEAR STUDENTS OF ENGLISH

LANGUAGE EDUCATION STUDY PROGRAM OF SANATA

DHARMA UNIVERSITY

A ThesisPresented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Sarjana Pendidikan Degree

in English Language Education

By

ANDREAS DIMAS ARDITYA Student number: 021214038

ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGE AND ARTS EDUCATION FACULTY OF TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION

SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA

STATEMENT OF WORK ORIGINALITY

I honestly declare that this thesis which I wrote does not contain the works or part

of the works of other people, except those cited in the quotations and

bibliography, as a scientific paper should.

Yogyakarta, 9 February 2007

The Writer

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My gratitude goes to my major sponsor, Dr. F.X. Mukarto, M.S. I am also

indebted to my cosponsor, C. Tutyandari, S.Pd, M.Pd.

I wish to thank the third year students of English Language Education

Study Program of Sanata Dharma University who have volunteered themselves

participating in this study.

My appreciation also goes to my beloved ones who have supported me in

my ups and downs. I wish to acknowledge all my colleagues and fellows, whose

list of names is too voluminous to be written here. I am grateful to those who have

directly or indirectly helped and supported me in writing this thesis.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TITLE PAGE ... i

PAGE OF APPROVAL ... ii

PAGE OF ACCEPTANCE ... iii

PAGE OF DEDICATION ... iv

STATEMENT OF WORK ORIGINALITY ... v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... vii

LIST OF TABLES ... x

LIST OF FIGURES ... ABSTRACT ... ABSTRAK ... CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background ... 1.2 Problem Identification ………..……….. xi xii xiii 1 3 1.3 Problem Limitation ... 1.4 Problem Formulation ... 1.5 Research Objective ... 1.6 Benefits of the Study ... 1.7 Definition of Terms ... CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW 4 5 5 6 6 2.1 Theoretical Description ... 9

2.1.2 Knowledge of Vocabulary ...

2.1.3 Writing Process and Writing Feature ...

2.1.4 Vocabulary in Writing Process ...

2.1.5 Measurement of Productive Vocabulary in Composittions ...

2.2 Theoretical Framework of the Study ...

CHAPTER 3 METHODOLOGY

11

14

17

18

20

3.1 Method ………...

3.2 Research Participants ………...

3.3 Data Source and Nature of Data ...

3.4 Data Collection ...

3.5 Data Analysis ... 22

23

24

25

25

CHAPTER 4 RESEARCH RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Data Presentation of Written Works ...

4.2 Analysis Results and Discussion of the Lexical Richness ...

4.2.1 Degree of Lexical Variation ...

4.2.2 Degree of Lexical Sophistication ..………...

4.2.3 Degree of Lexical Density ...

CHAPTER 5 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

5.1 Conclusions ...

5.1.1 The Third Year Students’ Lexical Variation Degree in Their

Written Work ...

5.1.2 The Third Year Students’ Lexical Sophistication Degree in Their

Written Work ………...

5.1.3 The Third Year Students’ Lexical Density Degree in Their

28

30

30

33

35

39

39

Written Work ...

5.2 Recommendations ...

5.2.1 to the Lecturers ...

5.2.2 to the English Learners ...

5.2.1 to Other Researchers ...

BIBLIOGRAPHY ...

APPENDICES ...

Appendix A. Table of Number of Words, Word Families, Low Frequency

Word Families, and Content Words Counts ...

Appendix B. Tables of Scores of Lexical Variation, Lexical

Sophistication, and Lexical Density Measurements ...

Appendix C. List of Words Used in the Participants’ Composition and

Their Frequency ...

Appendix D. Samples of Third Year Students Written Works ...

Appendix E. Text Fragment of Published Research Report ... 40

41

41

41

42

43

45

46

48

52

64

LIST OF TABLES

Page

Table 4.1 The Table of Descriptive Statistics of the Written Works ………

Table 4.2 The Table of Descriptive Statistics of Lexical Variation

Measurement ………....………

Table 4.3 The Table of Descriptive Statistics of Lexical Variation

Measurement ………

Table 4.4 The Table of Descriptive Statistics of Lexical Density

Measurement ………...

Table 4.5 Top Ten Most Used Words in the Students’ Written Works …... 28

31

33

36

LIST OF FIGURES

Page

Figure 2.1 Chapelle’s vocabulary ability construct ...………...………

Figure 2.2 Hayes’ Writing Model General Organization …...……….. 12

ABSTRACT

Arditya, Andreas D. 2007. A Study on the Lexical Richness in the Written Work of Third Year Students of English Language Education Study Program of Sanata Dharma University. Yogyakarta: English Language Education Study Program, Sanata Dharma University.

Vocabulary is the bridge between what message is meant to be delivered and what message is actually delivered. There seems to be an agreement among researchers that lexical ability is given more emphasis in writing skill than it is in the other skills. Writing possesses greater lexical density: it is densely packed with information, less redundant and more fully formulated to fulfill the needs of a distant reader and to avoid ambiguity; suggesting that written work draws on a large supply of words.

This study investigated the lexical richness in the written work of third year students of English as Foreign Language in Indonesian university. The study was meant to find out three measurements of lexical richness: (1) the degree of the lexical variation, (2) the degree of the lexical sophistication, and (3) the degree of the lexical density in students’ written work.

The method used was document analysis on students’ written works. Descriptive statistics was used to determine how accurately inductive reasoning can be employed to infer that what was observed on the sample in this study would be observed on the third year students’ population. Cluster sampling was used to represent the third year students of English Education Study Program of Sanata Dharma University. The students’ written works were uploaded into a computer and Simple Concordance Program 4.07 was used to analyze the lexical statistics of the data.

ABSTRAK

Arditya, Andreas D. 2007. A Study on the Lexical Richness in the Written Work of Third Year Students of English Language Education Study Program of Sanata Dharma University. Yogyakarta: Program Studi Pendidikan Bahasa Inggris, Universitas Sanata Dharma.

Kosakata adalah jembatan antara pesan yang dikirimkan dan pesan yang diterima dalam komunikasi bahasa. Dikatakan bahwa kemampuan kosakata mendapat penekanan lebih dalam keahlian menulis, dibanding dalam keahlian keahlian bahasa lain. Karya tulis memiliki kepadatan leksikal lebih besar: informasi lebih padat, penggunaan bahasa lebih efektif, dan dibuat untuk memenuhi kebutuhan pembaca dan dengan tingkat ambiguitas rendah; menunjukkan bahwa karya tulis bersandar pada kemampuan kosakata.

Studi ini meneliti kekayaan leksikal pada karya tulis mahasiswa Bahasa Inggris tahun ketiga di Indonesia. Penelitian kekayaan leksikal dilakukan untuk mencari: (1) tingkat keragaman kosakata, (2) tingkat penggunaan katakata sulit, dan (3) tingkat kepadatan leksikal dalam karya tulis mahasiswa.

Metode yang digunakan dalam studi ini adalah analisis dokumen pada karya tulis mahasiswa. Statistika deskriptif digunakan untuk menentukan apakah hasil observasi pada sampel dapat digunakan untuk mewakili seluruh popuplasi mahasiswa tahun ketiga. 49 sampel digunakan untuk mewakil mahasiswa tahun ketiga Progam Studi Bahasa Inggris Universitas Sanata Dharma. Karyatulis mahasiswa dipindai ke dalam komputer dan program komputer Simple Concordance Program 4.07 digunakan untuk membantu analisa data statistik kosakata.

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

This chapter places the current research among previous research,

especially those dealing with lexical characters and/or abilities of students of

English as a Second or Foreign Language. This chapter consists of background of

the study, problem identification, problem limitation, problem formulation,

research objectives, benefit of the study, and definition of terms.

1.1 Background

Research in vocabulary has been various in kinds. According to Johnson

(2000, p. 177) these last decades were period of strong interest in vocabulary.

During the time, educators became convinced that most words probably are

learned from oral and written context—that is, through listening and reading. The

emphasis of the period, as during the earlier period, was predominantly on

reading and learning words as way to improve comprehension.

Although much less attention has been paid to lexicon than other parts of

language, lexicon is an important factor in second language acquisition. This

importance is noted by Gass (1988b, as cited in Gass and Selinker, 2001, p. 372)

who observed that utterances with grammatical mistakes can be generally

understood, but lexical mistakes lead to interference of the communication. This

is because lexis corresponds closely with the meaning. Bloom (2000, as cited in

the intended meaning cannot be produced and, thus, is not comprehended, then the

communication is a failure. Lexicon is the bridge of what message is meant to be

delivered and what message is actually delivered. As Levelt (1989, as cited by

Gass and Selinker (2001), p. 373) put it, “…lexicon is an essential mediator

between conceptualization and grammatical and phonological encoding...”

In writing skill, the lexical ability is given more emphasis than it is in

other skills. Composition process makes written work more concise, formulated

and explicit. Halliday (1985, cited in Nunan, 1991) pointed out that writing

possesses greater lexical density. Written work is densely packed with

information, it is less redundant. Written work is also more fully formulated to

fulfill the needs of a distant reader and to avoid ambiguity. These suggest that

written work draws on a large supply of words.

Hayes and Flower (1980, as cited in Hayes, 2000) articulated a cognitive

process theory of writing. They refer to three writing processes: planning—which

includes goal setting and organizing, translating, and reviewing. Word selection

comes into play during any of these three writing processes, and each word chosen is important. Each word that comes into a growing text gives impact to the

text; any words or choices of words coming after will be determined and limited

by the word.

Analyzing students’ written work can reveal their lexical characteristics.

The description of students’ vocabulary ability is available on the text they have

written. Laufer (1991) used free compositions written by English learners as

source of lexical richness data on determining their second language vocabulary

namely: lexical variation, lexical density, lexical originality and lexical

sophistication.

In the local context, Susilo (2001) and Saputro (2005) studied vocabulary

of English students in university in Indonesia. Susilo investigated the controlled

active vocabulary size, using Laufer and Nation’s controlled active vocabulary

test. His study, which was crosssectional, aimed to find out whether differences

exist on students at different levels. Saputro’s investigation was also cross

sectional. He used students’ impromptu written compositions using The Passport

to IELTS to measure lexical density and lexical profile of the students.

The current study is a follow up to Saputro’s study. The study measures

the vocabulary characteristics of English students of the English Department in

university in Indonesia using their written works which are part of task they have

to do in their Writing V class.

1.2 Problem Identification

One way to analyze the students’ vocabulary in their written production is

by calculating various statistics that reflect their vocabulary knowledge. Read

(2000) summarized a set of statistical analyses toward written production. The

general term that is used for the vocabulary characteristics measured by these

statistics is lexical richness. Lexical richness analyzes four lexical features of a

written work, namely: lexical variation, lexical sophistication, lexical density and

number of errors.

Lexical variation, or also known as typetoken ratio, is the use of a variety

compares the number of different lexical words used in the text with the total

number of the running lexical words used in the text.

Lexical sophistication is the use of a selection lowfrequency words that

are appropriate to the topic and style of the writing, rather than general everyday

vocabulary. The measurement compares the number of the sophisticated word

families used in the text with the total number of word families in the text.

Lexical density is the use of lexical words in a text. The measurement

compares the number of lexical or content words, which consists of nouns, full

verbs, adjectives and adverbs derived from adjectives, with the total number of

words in the text

Number of errors is the occurrence of lexical errors in a text. The

classification of what are included as lexical error can be varied including minor

spelling mistakes, major spelling mistakes, derivation mistakes, deceptive

cognates, interference from another language learning, confusion between two

items, etc.; depending on what is expected to be revealed of the counting.

1.3 Problem Limitation

The main emphasis of this study is on analyzing three out of four aspects

of the lexical richness, namely, the lexical variation, lexical sophistication, and

lexical density of the written work of third year students of English Education

Department of Sanata Dharma University. Measurement on number of error is

not included in this study because the measurement was the most subjective of all

measurement occurs because researchers are likely to have different identification

of lexical errors one another; their findings may be too different for them to have

a high level of agreement or interrater reliability. Read also added another

limitation for the errors measurement, which is the generalization of seriousness

errors: the measurement does not take into account the relative seriousness of

different errors.

1.4 Problem Formulation

The intention of this study is to find out the Lexical Richness of the third

year students of English Education Study Program of Sanata Dharma University.

As has been explained above, although lexical richness in its respect is composed

of four elements—namely lexical variation, lexical sophistication, lexical density

and number of lexical errors—with regard to students’ written work of English

Education Department, this study strives to answer three questions:

1. What is the degree of the Lexical Variation in students’ written work?

2. What is the degree of the Lexical Sophistication in students’ written

work?

3. What is the degree of the Lexical Density in students’ written work?

1.5 Research Objective

This study aims to find out the Lexical Richness of EED students, which

is interpreted from their written works’ statistical scores of Lexical Variation,

1.6 Benefits of the Study

To give contribution to English Language Teaching (ELT), This study is

hopefully able to: (1) offer insight for ELT teachers in perceiving vocabulary

knowledge usage—use of word types, specific vocabulary, and text’s vocabulary

density—especially in written composition of third year university students, (2)

provide ELT teachers and readers with understanding of how vocabulary

characteristics can be inferred from written work, and (3) give description of

productive vocabulary characteristics in written composition of EEDUSD third

year students.

1.7 Definition of Terms

Some terms are used in this study; therefore, to avoid misunderstanding, it is necessary to explain the terms based on relevant sources.

1.7.1 Word Family

This study analyzed documentary data of written text; then for practical

reason lexical item—that is, a word—was basically defined as

orthographic words, that is “…any sequence of letters (and a limited

number of other characteristic such as hyphen and apostrophe) bounded

on either side by a space or punctuation mark” (Carter, 1998). However,

since a lexical item can have various forms, in this study lexical item is

family, which is a fundamental unit underlying different grammatical

variant or wordforms. For example, ‘makes’, ‘made’, ‘making’ etc. are

underlain by the capitalized lexeme ‘MAKE’ and are counted as

‘MAKE’.

1.7.2 LowFrequency Item

Laufer (1991) defined lowfrequency item as “advanced word” and what

is included as this kind of word would depend on the level of the learner.

In this study “advanced word” is taken to be words that are not in the top

two bands of Collins Cobuild’s (2001) most frequent English word. The

words in the top two band account for approximately 75% of all English

usage. There are 1720 words in the top two bands list. Words that are not

included in the bands are topic specific and advanced words.

1.7.3 Content Word

Content word is “…word that has meaning in isolation and serve more to

provide links within sentences.”(Read, 2000, p.18). In this study content

words are nouns, full verbs, adjectives and adverb derived from adjectives

occurred in the students’ compositions

1.7.4 Lexical Richness

The term is a generic term Read (2000, p.200) used to subordinate four

sophistication, lexical density and number of errors. In this study lexical

richness refers to the first three.

1.7.5 Written Work

Written work is intellectual composition produced as readable text. In this

study written work are the written compositions of the EED students that

consist of no less than 300 running words and no more than 500 running

words. The texts are of argumentation type and are in their draft form,

that is, the texts have gone through process of planning, drafting; but not

revision, redrafting and final drafting. Further description of the nature of

the written work used in this study is explained in Section 3.3.

1.7.6 Third Year Students of English Language Education Department The students study English as a Foreign Language. They are trained to

master English and to qualify as English teachers. The students may have

different traditional, ethnics or L1 background, but they are speakers of

Bahasa Indonesia as a national language and they all use Bahasa

Indonesia as lingua franca; therefore in the current study their

Chapter 2

LITERATURE REVIEW

There are several theories that eventually lead to ascertaining students’

lexical characteristic through statistical lexical analysis on their written work. This

chapter is dedicated to give a deeper topic understanding of the study. A number

of components on related points of the topic will therefore be clarified.

2.1 Theoretical Description

This section discusses how a word is defined; and how vocabulary is

described as a part of language competence, and used in the written process. This

section ends in discussion on, as the focus of this study, analyzing vocabulary in

written production.

2.1.1 Definition of Word

Carter (1998, p.4) discussed several definitions and their related problems

of a ‘word’. When we want to define the meaning of ‘word’, we tend to directly

think of it as a sequence of letters (and a certain added characteristics such as

apostrophe, hyphen, etc.) which is stringed together between spaces or

punctuation marks. This kind of word definition is an orthographical one.

Generally this kind of definition has considerable practical validity, for instance in

counting words or making wordlist. However, this definition has its problems. For

example, should we take swim, swims, swimming, and swam as separate items?

railway line, fishing line and straight line represents different items in one

orthographic word. Other polysemous words can have more extended meanings

and grammatical categories.

A more complex (and maybe more accurate) definition of ‘word’ is a

minimum meaningful unit. But again, questions rise. Do we considerdining room,

airport tax, and cannon ball as single item? How about ambiguous compound

nouns and phrasal verbs? And what meaning do my, if, by, but, could, because,

indeed, etc. represent? The last few items represent words with less semantical

sense and more grammatical one. Another definition may better serve this kind of

words, that is, ‘word’ is a minimal free form.

This definition, which was originally Bloomfield’s, derives that a word

should have ‘positional mobility’ and ‘internal stability’. A word should be able to

move from its particular point in a sentence. Thus, for example, the sentence I

walked across the room quietly can be reordered as I quietly walked across the

room or quietly I walked across the room or the room I walked across quietly.

Also, the morphemes in a word have relatively consistent sequence to one

another; making the morphemic constituents of quietly, walked and across are

fixed, that is, not possibly permutated into *leiuqty, *tuqeily, *kwaled, *leawkd,

*croass, *rosarcs, etc. Singleton (1999, p.14) argued that the grammatical

definition is the least problematic, because it gives a word stability which prevents

further division or reduction, and an ability to stand on its own. However,

although possible it is very rarely do we see could or if occur on their own. And

fixed items which may lose meaning if reduced, can be substituted by a single

word and still can stand on their own. As Carter (1998, p.6) exemplified it:

Q: Is it raining hard?

A: Cats and dogs.

A further definition that a word will not have more than on stressed syllable does

not add any satisfaction.

One theoretical notion that can be used to overcome these problem

definitions is lexeme. A lexeme is the abstract unit which underlies some related

word variants. This notion shares essential view with what ‘word family’ enclose,

which is a set of word form sharing a common meaning. Carter (1998, p.7) used

upper case form to denote lexeme. Thus upper cased LEAK is the lexeme which

underlies grammatical forms of leaks, leaked, and leaking. Lexeme can also be

used for items consisting of more than a word form. For example, A PIECE OF

CAKE is a single lexeme because it underlies a definite meaning. Polysemous

words will also be represented by several lexemes although they use the same

word form. For example, we will have lexemes LAP 1 (noun and verb as in race),

LAP 2 (verb as inthe cat laps the milk), and LAP 3 (noun as insit on my lap).

2.1.2 Knowledge of Vocabulary

Read (2000, p.2835) discussed definition of vocabulary ability by

Chapelle (1994) which was based on Bachman’s general construct of language

ability. The definition includes ‘both knowledge of language and the ability to put

has three components: the context of vocabulary use; vocabulary knowledge and

fundamental processes; and metacognitive strategies for vocabulary use.

Figure 2.1 Chappelle’s Vocabulary Ability Construct

From the point of view of traditional vocabulary testing, context is the whole text that a testee draws on to interpret individual items within. However,

context should be seen more than just a linguistic phenomenon. There is also pragmatic knowledge which affects the vocabulary ability. Thus, the social and

cultural situations influences the meaning of the vocabulary used. For example, in Bahasa Indonesia, ‘iya banget’ would have no meaning whatsoever in a formal

situation like trial court; but in the situation of casual speech especially in the

younger generation the item will signify the user keen agreement on something said. Another example in casual youth American English is ‘no shit’; used as a

response of something said it expresses disbelieve or surprise, but used otherwise it would only send the harsh meaning of ‘shit’. Clearly then, pragmatic knowledge

For the vocabulary knowledge and fundamental processes component of

vocabulary ability, Chappelle (1994, cited in Read, 2000, p.3133) outlines four

dimensions. The first is vocabulary size, which refers to the number of words that

a person knows. Following Chapelle’s logic of a communicative approach to

vocabulary ability, Read (2000, p.32) pointed out that we should seek to measure

vocabulary size not only in absolute sense, but also in relation to particular

context of use; thus distinguishing, for example the learner’s vocabulary ability in

writing an essay from his/her vocabulary ability in discussing a football match or

reading an international newspaper. The second dimension is knowledge of word

characteristic. Some words are used with better knowledge of it than others; each

known words has its own range of understanding, from vague to more precise. For

example, in writing a composition a learner may miswrite effect in intention of

affect because he/she may know more about the latter one. Like the previous

dimension, the extent to which a learner knows a word varies according to the

context it is used. The third one is lexicon organization, which concerns the way

in which words and other lexical items are stored in the brain. The last dimension

is fundamental processes. These last two are processes that a user applies to gain

access to the knowledge of vocabulary, both for understanding and producing

vocabulary in speaking and writing.

The metacognitive strategies for vocabulary use are the strategies

employed by language user to manage the ways of using vocabulary knowledge in

communication. Most of the time these strategies are operated unconsciously, it is

only when communicating task become unfamiliar or cognitively demanding that

these strategies become more conscious. Learners have a particular need to use

function effectively in communication situation. A basic strategy used when

learners are attempting to produce vocabulary is simplification or avoidance. They

may avoid using a vocabulary item because not knowing or not confident about

producing it in its correct form. Some other general strategies includes:

paraphrasing (using telephone you can carry anywhere for cellphone) , language

switch (can I borrow your PENSIL?), and use of superordinate terms (saying tool

to replace hammer).

Richards (1976, cited in Meara 1996) gave a guideline in describing

vocabulary competence. He proposed that knowing a word means: a) knowing the

probability of encountering the word in speech or print; b) knowing the limitation

of using the word according to function and situation; c) knowing the syntactic

behavior associated with the word; d) knowing the base form of the word and its

possible derivations; e) knowing the associations between the word and other

words in the language; f) knowing the semantic value of the word; and g)

knowing many of different meanings associated with the word. Points b) through

g) are related to the productive aspect of vocabulary competence, on which this

study will focus, particularly in the written production.

2.1.3 Writing Process and Writing Feature

As part of language skills, writing is the last one to develop. In the course

of history human invented writing system long after they began to speak, while,

Although writing and speech comprise the productive skill of language

competence, they are essentially different. Kress (1994: 1734) argue that speech

and writing have a) distinctive grammatical and textual structure and organization;

b) different distinctive unit—the distinctive unit in writing is the sentence; c)

distinct social setting; d) different demands and e) distinct syntactic and textual

structure.

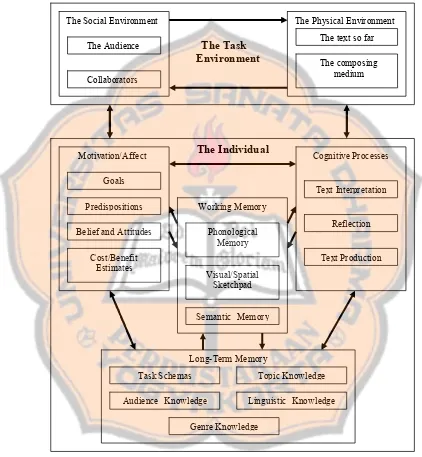

Hayes (2000) proposed a new writing model based on the 1980 Hayes

Flower model. Figure 2.2 depicts Hayes’ Writing Model general organization. In

his writing model writing process consisted of two components: the individual

and the environment. Hayes believes that writing depends on an appropriate

combination of cognitive, affective, social, and physical conditions if it is to

happen at all. First and foremost, writing is an intellectual activity requiring

cognitive process and memory, which subordinates, among others: phonological

memory, semantic memory, audience knowledge, topic knowledge, genre

knowledge and linguistic knowledge.

According to Silva and Matsuda (2002) in order for the writing process to

begin, the writer has to assess the rhetorical situation—i.e. a complex web of

relationships among the elements of writing: the writer, the reader, the text and

reality– and identify the primary purpose of writing, with a stress on one of the

elements of writing. Writer starts with the question “what is most important,

topically, to me in this text I am about to write.” What is paramount in writing is

the cohesive and continuous development of a topic, making the development

idiomatic, syntactic, morphological and lexical knowledge (Silva and Matsuda, 2002).

Figure 2.2 Hayes’ Writing Model General Organization

One variable which characterized writing is the physical absence of the audience or addressee—the reader. The language of writing is not generated in interaction. Although the audience may be known but the writer will not have

The Task Environment

The Social Environment The Physical Environment

Collaborators

The Audience The text so far

The composing medium

The Individual

Motivation/Affect Cognitive Processes

Goals

Predispositions

Belief and Attitudes

Cost/Benefit Estimates

Text Interpretation

Reflection

Text Production Working Memory

Phonological Memory

Visual/Spatial Sketchpad

Semantic Memory

LongTerm Memory

Task Schemas Topic Knowledge

Audience Knowledge Linguistic Knowledge

control who may see the text or under what circumstance is the text received. A written work is either filled with all necessary information for adequate interpretation and received well, or it is not and communication fails. Consequently, writing tends to have greater explicitness and elaboration.

2.1.4 Vocabulary in Writing Process

Being able to understand a word requires different approach from using

the word in speech or writing. To make it explicit, the ability to use a word

requires extended knowledge beyond what is needed to understand it. Unlike the

situation in reception, higher level of knowledge is involved in production. Brown

and Payne (1994, cited in Muncie, 2002) argued that converting receptive

vocabulary into productive vocabulary is the final stage of vocabulary learning,

and composing a written work would be the place for this to happen. Writing

allows greater chances of experimentation and resources (e.g. time, articles,

dictionaries, etc.) for learners, which would enable them to use less frequent but

more appropriate words.

While writing gives advantages in vocabulary development, at the same

time vocabulary is one of the most important features in writing. In writing,

communication between writer and reader is done through words and patterns of

words. For communication to happen, the distant reader demands great

explicitness of words and clarity of the written text. This makes knowledge of

words is critical in writing, because it heavily affect the success of written

communication. Muncie (2002) opined that, based on earlier studies, a lack of

vocabulary proficiency is perhaps the best indicator of overall composition

quality.

2.1.5 Measurement of Productive Vocabulary in Compositions

Productive vocabulary use can be measured by calculating various

statistics of written production. Analyzing students’ written work can reveal their

lexical characteristics. The description of students’ vocabulary ability is available

on the text they have written. Read (2000, p.200) summarized four statistical

measurement of productive vocabulary; namely, lexical variation, lexical

sophistication, lexical density and number of errors. The general term for all these

measurements is lexical richness. Lexical richness measures the lexical features of

written productions.

Lexical variation (LV), or also known as typetoken ratio, is the use of a

variety of different words rather than a limited words used repetitively. Lexical

variation measures the number of different lexical items used in the text compared

with the total number of the running lexical items used in the text.

Lexical sophistication (LS) is the use of a selection lowfrequency words

that the writers used in appropriateness to the topic and style of the writing, rather

than general everyday vocabulary. It includes the use of technical terms and

jargon as well as the kind of uncommon words in expression of meanings in

precise and sophisticated manner. Lexical sophistication measures the number of number of words family / type

the low frequency word families used in the text compared with the total number

of word families in the text.

Lexical density (LD) is the use of lexical words in a text. Lexical density

measures the number of content words, which consists of nouns, full verbs,

adjectives and adverbs derived from adjectives, compared with the total number

of lexical items in the text.

Number of errors is the occurrence of lexical errors in a text. The

classification of what are included as lexical error can be varied including minor

spelling mistakes, major spelling mistakes, derivation mistakes, deceptive

cognates, interference from another language learning, and confusion between two

items.

However, before calculation can be done and in order to obtain reliable

statistics; several processes should be drawn first. Among them are manually

checking and deciding some words classified as lexical items or low frequency

ones respectively. This process requires human judgment even though computer

program can be used as instrument. Another important factor is that the variety of

length of texts may affect the figures obtained, which is why it is best in these

kind of statistical measure to do limitation of text length. number of lowfrequency word family

LS = x 100%

number of word family

number of content words

LD = x 100%

2.2 Theoretical Framework of the Study

Vocabulary ability has three main components: the context of vocabulary

use; vocabulary knowledge and fundamental processes; and metacognitive

strategies for vocabulary use. The first dimension of vocabulary knowledge and

fundamental processes is vocabulary size, which refers to the number of words

that a person knows. Vocabulary size measurement should not only be done in

absolute sense, but also in relation to particular context of use. The second

dimension is knowledge of word characteristic. Some words are used with better

knowledge of it than others; each known word has its own range of

understanding, from vague to more precise. Like the previous dimension, the

extent to which a learner knows a word varies according to the context it is used.

The productive aspect of vocabulary competence, particularly in the

written production is related to the ability of : a) knowing the limitation of using

the word according to function and situation; b) knowing the syntactic behavior

associated with the word; c) knowing the base form of the word and its possible

derivations; d) knowing the associations between the word and other words in the

language; e) knowing the semantic value of the word; and f) knowing many of

the different meanings associated with the word.

One main characteristic of written production is the physical absence of

the reader. A written work should be filled with all necessary information, or

communication fails. Consequently, written work tends to have greater

explicitness and elaboration, is densely packed with information, and is less

Statistical measurements of written production are used to asses the

degree of productive vocabulary ability. This study will measure lexical variation,

lexical sophistication, and lexical density of students’ written work to asses their

Chapter 3

METHODOLOGY

This chapter presents the methods of data gathering and analysis. This

chapter provides explanations for the kind of the data, data gathering instruments,

data collection, and data analysis and interpretations required for the study.

3.1 Method

The study was basically descriptivequantitative study, which referred to

investigation using already existing data and concerned with the collection and

analysis of data in numeric form. This kind of study made ready a general

question in mind about certain phenomenon and then with specific question and

specific focus; which made the research focused on certain aspect of the possible

data available in the context being described (Seliger and Shohamy, 1989).

Furthermore, this study could be classified as documentary analysis research,

which analyzed collected document data from several units or individuals that had

already formed or existed in natural context at a given time. This research

collected students’ written work responses to their teachers’ assignment.

The descriptive statistics was used in analyzing the numerical data

interpreted from the written work. This research studied the individuals’

phenomena as group phenomena and treated the characteristics of individuals that

occurred in the measurement as the group’s characteristic. The descriptive

statistics was used to determine how accurately inductive reasoning can be

observed in the whole (the third year students). Thus, the study was concerned

with the generalized statistics, in which data were abstracted from a number of

individual cases.

Given the descriptive nature of the study, statistical analysis was done on

the numerical data. To decide the typical value of the lexical characteristics of the

group, the central tendency measures was applied the mean, and the median. The

central tendency was used as generalization of the groups’ lexical characteristics.

To decide how the central tendency would best represents the lexical

characteristics of the group, that is, whether it was appropriate to use the central

tendency as generalization of the group, information on data variability (standard

deviations) was also obtained.

3.2 Research Participants

To be able to have unbiased representation of data this study used

probability sampling, in which samples were drawn randomly from the

population. Because probability sampling sought representativeness of the

population, probability sample would have less risk of bias.

The subject of the study was 49 written works of third year students of

English Education Program of Sanata Dharma University. Initially the target

subject of this study was 50 (10 from each Writing V class), but after analyses

were done one subject failed to fulfill the criteria of minimum word number. The

students were generally between 1920 years of age. They have gone through the

learning in the university. Their knowledge of English as second language was

categorized as advanced.

3.3 Data Source and Nature of Data

From each of the participants a written work was collected. The

participants composed the written work as the first draft of a writing task given by

their lecturers in Writing V course. The written work was of argumentation type

or genre of writing, in which they were to take a position of on a certain issue and

defend their stand. First draft form meant that the participants made a structure

plan and drafted their written works; but the written works have not gone through

revision (either by selfcorrection or by lectures consultation), redrafting and re

revision before they were submitted to the lectures. The students worked on

written composition for two to three weeks period; from the time the students

were given assignments to the submission task date. The draft form represented

the students’ real productive vocabulary knowledge on the words they used

without being affected, and therefore disturbed, by other authorities.

The written works were collected from lecturers at different times from 1 –

15 September 2006. From each class 10 works were chosen randomly without

regard to name, student numbers, sex, and topic.

Only 300 to 500 first words of each student’s written work were used as

data, this is due to lexical richness known instability and sensitivity when

confronted with various text lengths. The 300 to 500 firstwords limitation was

done in order to reduce the impact of text length on the index of lexical richness

The analyzed words were the English words used in students’ written works; all

other words and illustrations that were found e.g. Indonesian words, names of

person and numbers were considered irrelevant and not counted.

3.4 Data Collection

The compiled 50 students’ written works were uploaded to computer, and

using the Simple Concordance Program (henceforth SCP) computer software a list

of words used in the written work and their frequency of occurrences were made

for each work. These lists were the base data for calculating the lexical variation,

lexical sophistication, and lexical density measurement of each written work.

During this process one of the written works did not reach the minimum threshold

of word number and thus dismissed.

3.5 Data Analysis

Data analysis was begun after frequency of words occurrences list and

used words list was made for each written work. Each written work was later

analyzed using the three lexical richness measurements. The first is lexical

variation measurement. To measure the degree of lexical variation of a written

work is to divide the number of different lexical items used in the work by the

total number of lexical items in the work. For each written work the SCP had

provided the typetoken ratio, which by character is the same measure as lexical

variation, but the SCP was not able to list the words in word family, e.g. made,

manually reexamined and the recounted. 49 figures of lexical variation were later

tabulated.

Almost similar procedures were done for lexical sophistication and lexical

density. For lexical sophistication the number of lowfrequency word family used

in the work was divided by the total number of lexical items in the work. The low

frequency items of the written work were any word that are not in the Band 5 and

Band 4 of Cobuild’s frequency bands. The words in the two Bands are the most

frequent English words used. There are approximately 1720 words in these bands

and they account for about 75% of all English usage (Collins Cobuild, 2001).

Each of the 49 wordlists was examined manually using the “top two” list. 49

figures of lexical sophistication were later tabulated.

To measure lexical density the number of content words used in the work

was divided by the total number of lexical items in the work. Content words are

nouns, full verbs, adjectives and adverbs derived from adjectives. Again the 49

wordlists were examined. Noncontent words or otherwise known as function

words numbers were low in type but high in token, that is, limited but frequent.

Because it was easier to count words which were not content words, such was

done and then to have the number of content words the total number of words was

subtracted by the number of function words. 49 figures of lexical density were

later tabulated. For the sake of data presentation and interpretation convenience,

the output figures of measurements were presented in percentage. This process

gathered 147 figures—three figures for each of 49 written work.

To answer the first problem formulation of the study, that is to acquire the

lexical variations was used. For the mean, the lexical variation figures from each

work were summed up and then divided by 49. The standard deviation was later

calculated to measure the variability within group as to decide whether the mean

figure was an appropriate representation of the groups’ lexical variation degree.

The same was done also for the second and the third problem formulation, their

within group’s means and standard deviation were calculated for measurement of

lexical sophistication and lexical density of the group. The figures of means and

standard deviations, with additional information of ranges, min and max figures,

median figures, were tabulated. To give a better view on the analysis results of

the lexical measurements, in the discussion the participants’ degrees of lexical

richness was compared with that of a benchmark. The benchmark was a 400

word fragment of a research report which was published in ResearchNotes in

Chapter 4

RESEARCH RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This chapter consists of two main sections. The first section is data

presentation. It deals with the numerical scores of the written works i.e. number of

words, word families, low frequency items and content words. The results of data

analyses and discussion on the findings are presented in the second section, which

covers the answers to the study’s research questions: to find out the third year

students’ degree of lexical variation, lexical sophistication and lexical density.

4.1 Data Presentation of the Written Works

The study researched a group of students regarding its lexical richness of

written work. With accordance to the measurements in lexical richness, the results

of data collection were presented scores by scores.

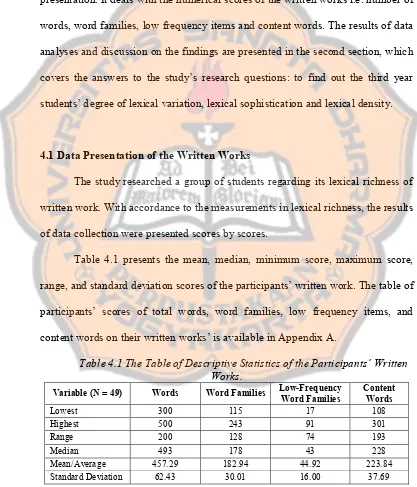

Table 4.1 presents the mean, median, minimum score, maximum score,

range, and standard deviation scores of the participants’ written work. The table of

participants’ scores of total words, word families, low frequency items, and

content words on their written works’ is available in Appendix A.

Table 4.1 The Table of Descriptive Statistics of the Participants’ Written Works.

Variable (N = 49) Words Word Families LowFrequency Word Families Content Words

Lowest 300 115 17 108

Highest 500 243 91 301

Range 200 128 74 193

Median 493 178 43 228

The table shows that the number of participants’ produced words, with the

range of 200 words, for the lowest was 300 and the highest 500. As explained in

section 3.3, the limitation on the length of written works used in measurement is

important to stabilize measurement results. Central tendency scores of produced

words in the participants’ written works show that the average number was about

450 words and the median 490 words. The number of participants’ produced

words standard deviation 62.43 indicates that the dispersion of the written works

length is quite low. Furthermore, more than 70% (35 out of 49) of participants’

written works consisted of 450500 words. This low dispersion of numbers of

words would help to eliminate the flaws of lexical richness measurements due to

instability and sensitivity to various text lengths.

Participants’ produced word family number, with range of 128, was 115 at

the lowest and 243 at the highest. The extreme number 115 occurred in the word

family numbers, differing 21 points from the second lowest number 136.

However, this atypicality should not affect the participants’ average number. The

average number of the participants’ word family was about 180, while the median

was 178. With the standard deviation for the participants’ word family numbers

30.01, more than 60% (31 out of 49) participants’ produced 160220 word

families in their written works.

The number on lowfrequency word families was at lowest 17 and the

highest 91, ranging at 74. In average the number of participants’ lowfrequency

items was about 44, and not far from that the median was 43. With the

more than 65% (33 out of 49) participants used 3060 low frequency word

families in their written works.

Participants’ content words number varied between 108 and 301, ranging

by 193. The average number was about 220 and the standard deviation was 37.69.

These numbers showed that participants used 200250 content words in their

written works.

4.2 Analysis Results and Discussion of the Lexical Richness

In order to answer the research problem formulations and to present a

detailed discussion of the data analysis, this section is divided into three parts: (1)

analysis and discussion on the third year students’ lexical variation, (2) the

analysis and discussion on the third year students’ lexical sophistication, and (3)

the analysis and discussion on the third year students’ lexical density. The whole

computations were done by using SCP and Microsoft Excel computer programs.

4.2.1 Degree of Lexical Variation

Lexical variation is the tendency of using word family repeatedly. The

assumption is that the more repetition of word family there is in his/her written

work, the smaller quantity of lexical repertoire the participant has. The

measurement of lexical variation was done by dividing the number of word

families with the number of words used.

The lexical variation analysis results of the written works of the third year

students of English Education Program of Sanata Dharma University: the mean,

Table 4.2 and the table of entire results of lexical variation is available in

Appendix B.

Table 4.2 The Table of Descriptive Statistics of Lexical Variation Measurement. Score (%)

Lowest 30.85

Highest 52.37

Range 21.52

Median 39.63

Mean/Average 40.26 Standard Deviation 5.45

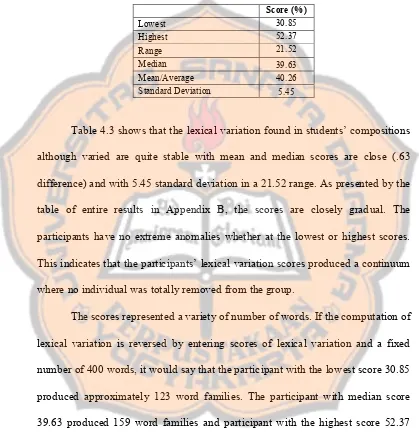

Table 4.3 shows that the lexical variation found in students’ compositions

although varied are quite stable with mean and median scores are close (.63

difference) and with 5.45 standard deviation in a 21.52 range. As presented by the

table of entire results in Appendix B, the scores are closely gradual. The

participants have no extreme anomalies whether at the lowest or highest scores.

This indicates that the participants’ lexical variation scores produced a continuum

where no individual was totally removed from the group.

The scores represented a variety of number of words. If the computation of

lexical variation is reversed by entering scores of lexical variation and a fixed

number of 400 words, it would say that the participant with the lowest score 30.85

produced approximately 123 word families. The participant with median score

39.63 produced 159 word families and participant with the highest score 52.37

produced 210 word families in a 400 words composition. This would give 87

word families difference between the lowest and the highest participants. The

mean 40.25 score would represent the third year students’ productive ability of

Before going to the discussion of the students’ lexical variation degree let

us keep in mind that students of English as Second Language are called upon not

only to 'know' vocabulary items, but also to use them in production, which in our

case, in the written production. Usage of these items in actual linguistic situations

is superior to mere understanding or recognition. Furthermore, correct use of

items would mean that the lexical items are not only part of the lexical repertoire

of a learner, but that they can be activated at will, and even better, flexibly. Active

knowledge of a large lexical repertoire may have more influence on a learner's

vocabulary production; such influence which may not observable in the

performance of a learner with smaller lexical repertoire.

The third year students’ inclination to repeat the same words in the

compositions—i.e., their lexical variation—was 40.26%. The 5.45 standard

deviation indicates that there is low dispersion of lexical variation scores among

the students. Despite the existing variance within the group, the students share an

average lexical variation characteristic. This percentage means that in their

composition the students used each word family roughly 2.5 times (from 100%

divided by 40.26%). To make a comparison, a 400word published research report

fragment was uploaded to the SCP computer program and its degree of lexical

variation was counted. The result was that the fragment’s lexical variation was

50% (2 times repetition per word family). Assuming that this fragment was

produced by a highly proficient English user and taking the general principle that

more proficient users use a wider range of vocabulary than less proficient ones

(Read, 2005), the third year students’ 40.26% lexical variation would be a quite

active word repertoire was likely not far below that of the highly proficient.

Furthermore, the students seemed to have in their hands a fair readiness to draw

on an accessible and retrievable lexicon as needs demands.

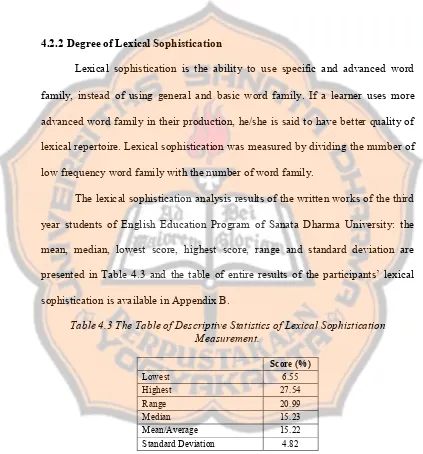

4.2.2 Degree of Lexical Sophistication

Lexical sophistication is the ability to use specific and advanced word

family, instead of using general and basic word family. If a learner uses more

advanced word family in their production, he/she is said to have better quality of

lexical repertoire. Lexical sophistication was measured by dividing the number of

low frequency word family with the number of word family.

The lexical sophistication analysis results of the written works of the third

year students of English Education Program of Sanata Dharma University: the

mean, median, lowest score, highest score, range and standard deviation are

presented in Table 4.3 and the table of entire results of the participants’ lexical

sophistication is available in Appendix B.

Table 4.3 The Table of Descriptive Statistics of Lexical Sophistication Measurement.

Score (%)

Lowest 6.55

Highest 27.54

Range 20.99

Median 15.23

Mean/Average 15.22 Standard Deviation 4.82

The participants scored at variety from as low as 6.55 to as high as 27.54,

ranging the scores by 20.99. Table of entire results of participants’ lexical

were used at more than 1 at each 4 word families rate, which made the particular

participant’s written composition was highly specific. But the table also shows

opposite extreme that in two written works only less than 9% of the word families

were low frequency items. However, with extreme scores occurred at both ends,

variability remains low as indicated by standard deviation 4.82. Again, as it was in

the lexical variation scores, variance remains low within the group’s lexical

sophistication scores. In average the third year students scored 15.23 on lexical

sophistication. This means that more than 15% of the total words families they

used in their written works were Collins Cobuild’s low frequency word families.

The third year students have shown that in terms of specific and advanced

word family they have managed well in their vocabulary choices. 15% of the total

word families they used were low frequency items. The same lexical measurement

done on the 400word published research report fragment resulted that the highly

proficient English user had scored 16 % in lexical sophistication. This is what

Read (2005) has asserted that the vocabulary use of higher proficiency students

was more sophisticated than that of those at the lower levels.

Scarcella and Zimmerman (1998) noted that there seemed to be an

agreement among scholars that the ability to access and use sophisticated lexical

register where setting demands is important in academic success. ESL students

who are unable to change lexical gears and shift from an informal, conversation

register to an analyticalacademic register encounter more and more difficulties as

the demands increase. This is given more emphasis especially in writing, because