Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Linking Faculty Development to the Business

School's Mission

Leonardo Legorreta , Craig A. Kelley & Chris J. Sablynski

To cite this article: Leonardo Legorreta , Craig A. Kelley & Chris J. Sablynski (2006) Linking Faculty Development to the Business School's Mission, Journal of Education for Business, 82:1, 3-10, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.82.1.3-10

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.82.1.3-10

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 42

View related articles

ABSTRACT. Recently adopted

stan-dards by the International Association to

Advance Collegiate Schools of Business

(AACSB) require accredited schools to

define a set of specific goals and

student-learning outcomes from their mission

state-ments. In addition, AACSB Participant

Standard 11 requires a school to design

fac-ulty development programs to fulfill the

school’s mission. What is missing in the

business education literature is a

descrip-tion of how the school can link its faculty

development efforts to the achievement of

its stated goals and student-learning

out-comes. This article proposes a model to

foster the link between mission statement,

goals, student-learning outcomes, and

fac-ulty-development programs.

Key words: faculty-development, mission

statement, student-learning outcome

Copyright 2006 Heldref Publications

ecent changes by the International Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB, 2005) to its standard herald a new perspective for the accreditation process and business school management. These changes pro-vide an opportunity to align a school’s mission with its practices. The AACSB standards require that the business school’s mission statement drive all decision making, including faculty cov-erage of courses, learning objectives, intellectual contributions, and faculty-development programs.

Implicit in the AACSB (2005) stan-dards is the recognition that individual faculty member’s contributions will dif-fer. The AACSB standards are silent on how to comply with the new aggregate faculty goals and mission-centric per-spective. Schools can tailor their plans to suit their faculty profiles. This places the faculty-development plan (FDP) in a unique mediating position. A properly construed FDP can aid the transition from mission formulation to implemen-tation in alignment with individual fac-ulty members’ needs and aspirations, can provide a systematic approach for dealing with a complex and dynamic problem, and can add transparency and flexibility to the accreditation process.

Several studies have been published on addressing several of the AACSB standards (e.g., Pritchard, Potter, & Sac-cucci, 2004; Smith & Rubenson, 2005;

Weber, Weber, Sleeper, & Schneider, 2004). Our purpose in this article is to fill a gap in the literature by presenting a process that links faculty development to school goals and student learning objectives. To accomplish this purpose we (a) examine the relationship between faculty development and school mis-sion, (b) provide a tool for linking the school mission to faculty development, (c) explore how this tool fits with the business education literature, thereby opening opportunities for further devel-opments, and (d) offer a top-down per-spective that summarizes the merits and challenges of this approach.

What Is Faculty Development?

The term faculty development has been used in many ways in the business-education literature. Faculty develop-ment has been used synonymously with the enhancement of teaching (Millis, 1994) and research (Bland & Schmitz, 1990). Festervand and Tillery (2001) defined faculty development as a “set of activities that promote the creation of knowledge” (p. 109). They suggest that the outcomes of faculty development can be measured through each faculty member’s teaching, research, and ser-vice. Blignaut and Trollip (2003) take a narrower approach to defining faculty development. They suggest faculty development may take the form of

spe-Linking Faculty Development to

the Business School’s Mission

LEONARDO LEGORRETA CRAIG A. KELLEY CHRIS J. SABLYNSKI

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO SACRAMENTO, CALIFORNIA

R

cialized training in how to use technolo-gy to teach an online course. DiLorenzo and Heppner (1994) advise against tak-ing such a narrow view of faculty opment. They approach faculty devel-opment from a departmental perspective and recommend grouping faculty devel-opment efforts under four categories: (a) morale, (b) teaching, (c) research, and (d) time and developmental growth.

Although faculty development efforts can be very effective in enhancing teaching, there is a need to expand these programs into other areas of faculty life (Millis, 1994). AACSB Assurance of Learning Standards related to assess-ment have placed greater demands on faculty to be accountable for how they allocate their time teaching. It is no longer sufficient to disseminate knowl-edge to students. Faculty members must demonstrate that their students have competence in the skills they must mas-ter to be successful in a business career. Faculty development in the broadest sense of the word encompasses teach-ing, research, career development, and personal health and growth (as cited in Millis, 1994). In this sense, DiLorenzo and Heppner (1994) discuss the scholar-ships of discovery, application, integra-tion, and teaching. Indeed, teaching, research, career development, and per-sonal health and growth can be integrat-ed under the scholarship rubric. There-fore, the vitality of the school depends on a holistic approach to faculty devel-opment (Bland & Schmitz, 1990).

AACSB standards have helped shape the faculty development activities in a variety of ways including the use of study-abroad programs (Festervand & Tillery, 2001), use of self-directed teams in the structure of a business school (Smith, Rubenson, & Bebee, 2002), and development of online teach-ing skills (Blignaut & Trollip, 2003). The need for faculty development also stems from the increased demands of accountability, in particular AACSB assessment. Millis (1994) identified several changes driving this demand, namely changing expectations about the quality of education, changing societal needs, changing technology, changing student populations, and changing teaching and learning paradigms. Dynamic complexity now characterizes

higher education, forcing collegiate schools of business to integrate and account for resource allocation. The more successful schools will be those that make faculty development a key strategic resource (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 2002).

The task of developing a model FDP involves managing diversity of interests, values, and stages in the professional growth of the faculty members. A one-size-fits-all FDP is not realistic for most schools. From the point of view of fac-ulty, priorities change as their careers develop (DiLorenzo & Heppner, 1994). From the point of view of teaching and research, different types of situations require different skills and resources (DiLorenzo & Heppner). However, diversity gives the professoriate its vitality. Thus, a model FDP must recog-nize different skills and needs of indi-vidual faculty members.

Different stages in academic careers means specific faculty development goals and programs must be adapted from faculty member to faculty mem-ber. All professional life-cycle models recognize that career paths vary greatly and that the path dependencies matter (DiLorenzo & Heppner, 1994). For example, some faculty members may find themselves transitioning into fields other than their own, yet because of their maturity as researchers, they will not need the same level of support typi-cally afforded to new faculty members even though both are relatively new to the field. The school administration should know each faculty member’s career objectives so it can provide the appropriate level of faculty develop-ment to help the faculty members achieve their objectives.

At a time when the rate of retirement of business faculty is increasing in par-allel with overall student population growth and new faculty are being added in large numbers, FDPs must recognize that the needs of junior faculty differ from those of more senior faculty mem-bers (J. Mondello, personal communi-cation, August 16–24, 2005; Sorcinelli, 1994).

Given potential shortages of junior faculty (Davis & McCarthy, 2005), a school’s willingness to learn about and to provide support for new faculty may

be critical to the school’s future success. A honeymoon effect takes place initial-ly when new faculty report high levels of satisfaction—the relative autonomy, the opportunities for intellectual discov-ery and growth, the opportunity to have a high impact on others, and the sense of accomplishment (Olsen & Sorcinelli; Sorcinelli; Turner & Boice, as cited in Sorcinelli, 1994). Over time, there is a downward turn, particularly with extrin-sic rewards (Sorcinelli, 1992). The fol-lowing concerns arise: time constraints in research and teaching; lack of colle-gial relations; inadequate feedback, recognitions, or rewards; unrealistic expectations; insufficient resources; and lack of balance between work and per-sonal life (Sorcinelli, 1994).

Shisler (1995) provides six ways for research administrators to personalize faculty development programs: (a) hold an open house; (b) meet with new facul-ty; (c) manage by walking around; (d) praise work well-done; (e) stage end-of-year events to express appreciation; and (f) show interest in the faculty members as professionals. These activities are uniquely germane to senior faculty mentors with research interests closely related to those of the junior faculty members.

Good arguments are offered for allo-cating primary responsibility for faculty development to the appropriate mentor within the school (DiLorenzo & Heppn-er, 1994). In general, primary faculty development responsibility could reside with the individual, with the department, with the school, with the university, or conceivably even at some interuniversity level. Although some responsibility should be distributed to all these levels, the canonical place is the mentor level because of the mentor’s understanding of the shared subject matter, familiarity with the discipline’s career cycle, and proximity to the issues facing the school. Moreover, vesting mentors with the responsibility for faculty development provides the school with (a) clarity and purpose, (b) the means to define the school’s future direction, and (c) occa-sions to take pride in the school’s accom-plishments (DiLorenzo & Heppner).

For DiLorenzo and Heppner (1994), the mentor comes from the individual faculty member’s department. We feel

this restriction is unnecessary. Although departments play a pivotal role in facul-ty development, an “appropriate” men-tor is not restricted to the individual fac-ulty member’s department. Whereas a departmental mentor offers insights into the research area, nondepartmental mentors can provide valuable insights into other aspects of the faculty mem-ber’s professional development.

School Mission

What Does AACSB International Mean by “Mission”?

Since 1991, AACSB has made mis-sion-linked standards and peer review the cornerstones of its accreditation process (AACSB, 2005). Despite this strong reliance on mission, the AACSB is notably silent on defining the term. The most explicit statements are the fol-lowing:

1. Mission Statement: The school publishes a mission statement or its equivalent that provides direction for making decisions. The mission state-ment derives from a process that includes the viewpoints of various stakeholders. The school periodically reviews and revises the mission state-ment as appropriate. The review process involves appropriate stakeholders.

2. Mission Appropriateness: The school’s mission statement is appropri-ate to higher education for management and consonant with the mission of any institution of which the school is a part. The mission includes the production of intellectual contributions that advance the knowledge and practice of business and management (AACSB, 2005).

3. To attain AACSB accreditation, schools must start with a clear and com-pelling mission; but the missions will vary according to localized business needs and concerns, cultures and tradi-tions, and the aims of governmental, religious, or other sponsoring organiza-tions (AACSB, 2005).

4. AACSB International accreditation assures stakeholders that business schools manage resources to achieve a vibrant and relevant mission (AACSB, 2005).

The presumption is that the shift to mission-linked standards would increase

AACSB accreditation access to institu-tions that historically focused primarily on teaching (Jantzen, 2000; Yunker, 1998). Thus, AACSB may be flexible in defining the term “mission” to allow for individual variances needed to accom-modate stakeholder diversity. Although AACSB allows for individual variances, it does not disregard the role research (intellectual contributions) must play in every accredited school. Schools have the responsibility of defining that role.

For AACSB, a mission is a published expression derived from a process that includes the viewpoints of various stakeholders and provides direction for making decisions. It must be “vibrant and relevant,” “clear and compelling,” appropriate to higher education for management, and “consonant with the mission of any institution of which the school is a part” (AACSB, 2005).

Linking Faculty Development and the School Mission

A business school’s goals and student learning outcomes only have meaning when they are intimately linked to the core values of the school (Dolan, Gar-cia, & Auerbach, 2003). Accordingly, core values are used to link faculty development with the school mission. Witcher (2003) breaks the process of linking faculty development and school mission into four phases: focus, align-ment, integration, and review (FAIR).

In the focus phase, the mission state-ment is converted into actionable steps. The process begins by breaking the core values inherent in the mission statement into an explicit list. This is used to gen-erate single-focus actionable goal state-ments. These are the goals of the school. The goals are ranked and rated accord-ing to the current strategic intent. The ordered list of goals with associated rat-ings is called the “ranked and rated goals of the school.” The ranked and rated goals of the school reflect the cur-rent strategic positioning of the school. In the alignment phase, all resources are directed toward the attainment of the mission statement. The presumption is that the resources available can effec-tively implement the mission statement. The school initiates a request for pro-posals and provides a rubric for

evaluat-ing the proposals. This faculty proposal rubric is the key link in the chain con-necting faculty development and the school’s mission. Rubrics are typically used for assessing student work. Extending rubrics to faculty develop-ment provides a common lens for all AACSB documents. The faculty pro-posal rubric must be based on the ranked and rated goals of the school. Therefore, each proposal is evaluated in light of the current strategic positioning of the school.

In the integration phase, a desired future is designed (Ackoff, 1981). This is the crucial link between faculty devel-opment and the school’s mission. The values embedded in the goals as rated and ranked by the present strategic intent will be meaningful to the faculty only if they are widely shared. This should provide direction and motivate faculty toward the kinds of activities most valued by the school. Here the role of the departmental mentor is crucial in helping individual faculty members determine their individual needs and in matching these to the call for proposals. It falls on the mentor to ensure that not only are the school’s current needs inte-grated with those of individual faculty, but also that every faculty member’s needs are being met from iteration to iteration (Nathan, 1994). However, the individual faculty member has responsi-bility to generate a proposal and to link it to the school’s mission through the use of the rubric. The faculty member is intimately aware of how his or her development needs are being played out against the mission of the school. The school then makes the assessment of the proposals in an open forum and allo-cates the resources accordingly. The open forum enables individual faculty members to witness the alignment of resources to proposals of the ranked and rated goals of the school, enabling a common vision of direction.

In the review phase, the process is mastered through improved iterations and disseminated best practices. First, the school evaluates the allocation plan in light of the ranked and rated goals of the school in an open forum. The trans-parency of the process allows all to see exemplary proposals in light of the cur-rent strategic positioning of the school

as well as pitfalls in the process. To inte-grate this feedback into the learning cycle, the school surveys the faculty to elicit feedback from the process and from the evaluation of the allocation plan. The ultimate goal of this approach is to generate faculty support of the development and implementation of the school mission. Hence, as a final step in the review process, the school takes inventory of faculty contributions so as to assess the tool’s effectiveness in elic-iting faculty buy in.

Although the process is iterative, the iterations do not need to be done annu-ally. The iterations can be carried out on any predetermined time period (e.g., annually or once every 3 years) that suits the strategic needs of the school. Appendix A summarizes the implemen-tation details of the four-phase FAIR approach previously discussed.

Case Example

The following discussion details the FAIR approach as used by the faculty in the College of Business Administration (CBA) at the California State University, Sacramento (CSUS), to link its school mission statement to its FDP. CSUS is a public university and part of the 23 cam-pus California State University system. It has an enrollment of approximately 28,000 undergraduate and graduate stu-dents. The CBA has approximately 4,000 undergraduate and 250 graduate students. Undergraduate business majors may select from 11 concentrations, including marketing, finance, accounting, manage-ment information systems, human resources management, general manage-ment, and international business. The stu-dent body is very diverse, reflecting the demographics of California.

The basic assumption made by the college’s faculty was that faculty devel-opment would focus on programs that advance the mission of the CBA. The CBA’s mission statement is as follows:

The College strives to be an exemplary regional educational institution graduat-ing community-minded students with a strong foundation in business knowledge, skills, and values. We offer a business education that is responsive to the chang-ing regional, global, and technology-dri-ven environment. We will fulfill our mis-sion through the pursuit of excellence in

teaching and learning, scholarship and service to our community as well as through collaborative efforts among, fac-ulty, students, staff, University, and com-munity members. (California State Uni-versity, Sacramento, n.d.)

Focus

Following the implementation process outlined in Appendix A, the CBA faculty developed a list of goals for the college based on a value-based analysis. The CBA faculty broke apart the school’s mission statement into component parts and then matched the parts with the core values of the CBA. The faculty then proceeded on to Step 1.2 of the process and developed 10 goals that captured the values inherent in the school’s mission. These goals are shown in Appendix B.

Each of the goals can be traced to a part of the mission. For example, Goal 1 is central to the mission of being an exemplary regional educational institu-tion. In some cases the goals overlapped different parts of the mission statement. Goal 2, for instance, is seeking to devel-op sought-after students and Goal 10 is encouraging students to engage in com-munity activities to promote the welfare of others. Both of these goals relate to the part of the mission that involves graduat-ing community-minded students.

Before proceeding on to Step 1.3, the goals underwent further refinement to generate single-focus subgoals. The sub-goals are listed Appendix B. For exam-ple, Goal 1 states “To improve perception of CBA from students, alumni, and regional organizations.” Depending on its current strategies, the CBA may choose to focus on one of these stakeholder groups over the others at a given point in time. Accordingly, Goal 1 can be broken down into three, single-focus goals:

Goal 1a: to improve student percep-tion of the CBA;

Goal 1b: to improve alumni percep-tion of the CBA; and

Goal 1c: to improve regional organi-zation’s perception of the CBA.

Not all goals on the list break down as easily. The actual breakout may depend on particular circumstances. However, the process is intended to be flexible so as to permit revision and edits.

Further refinements to the single-action goals are possible and should be done as needed to adequately rank com-peting faculty-development proposals. For Step 1.3 the single-action goals need to be rated and ranked through a consensus of the faculty and school administration. Step 1.3 ensures that competing faculty development propos-als are adequately rated, selected, and funded in alignment with the mission of the college and the current strategic intent of its leaders.

Align

The CBA’s Faculty Development Committee compiled an exhaustive list of all programs that can be made avail-able for faculty-development purposes at both the university and college levels. For Step 2.1, the college administration can select programs from this list to implement. This list helps to ensure that redundancies are minimized, given that resources available at the campus level can be used to relieve the college of part of the responsibility for funding faculty development programs.

The CBA’s current list of programs can be extended to list programs beyond the campus. Moreover, a policy can be developed that guides faculty members to seek support from the appropriate level—college, campus, or external— given the faculty members’ respective stages of professional development. Well-established researchers and teach-ers may be able to bid for campus and external support more readily than a junior faculty member can. Therefore, junior faculty members may need to be given priority over college-based resources, if it fits the strategic intent of the college.

In light of the ranked and rated goals of the school and funding sources, the school administration that makes resource allocation decisions will pro-vide appropriate resources through a call for proposals. This call for propos-als would list the available resources and provide a rubric for evaluating the proposals (Step 2.3). The rubric would clearly link the resource allocation deci-sion with the school’s misdeci-sion, which not only communicates the leaders’ strategic intent but also links the intent

to faculty development, thereby opti-mizing the alignment between strategic intent and operations.

Integrate

Each individual faculty member would prepare an FDP. The FDP would address the need to accommodate indi-vidual differences among faculty mem-bers that may be in different stages of their career. Per Step 3.1, a mentor would assist the faculty member in reviewing and updating the FDP and help find points of commonality with the strategic direction of the school as set out in the call for proposals. The mentor estimates how much support the faculty member is likely to receive at the college level and assist the faculty member when the FDP is not in line with the call for proposals.

Because there will be points of com-monality between the strategic intent of the college and the FDP of individual faculty members, the individual faculty members would be responsible for gen-erating proposals and for making initial assessments of the proposals on the basis of the rubric developed in Step 3.2. The final evaluation would be car-ried out at the college level, Step 3.3 in an open forum that makes the resource allocation decision transparent.

Review

The resource allocation plan maps the resource allocation decision across all proposals. As such it can be mapped against the “ranked and rated goals of the school” (Step 4.1). The school fac-ulty as a whole would then be surveyed to assess satisfaction with the resource allocation decision (Step 4.2). It could be that some faculty members might not have participated in the request for pro-posals while others might not have been awarded their requested resources. Assessing faculty participation will review the actual link between faculty development and the school’s mission.

Linking Mission, Goals, and Student-Learning Outcomes

The entire FAIR process can be car-ried out at the program level of analysis. The goal of the Bachelor of Science in

Business Administration (BSBA) pro-gram is to give the students the ability to:

1. Think with sufficient depth and agility to make sound decisions based on logical analysis and substantive, inte-grative knowledge of the business disci-plines. This outcome directly relates to Goals 3, 4, 7, 9, and 10.

2. Communicate clearly and effec-tively. Goals 4 and 7 are directly related to this outcome.

3. Understand how local, regional, national, or international circumstances affect business decisions. Goals 3, 4, 6, and 9 are related to this learning out-come.

4. Be proactive and anticipate changes in the environment that affect business decisions, current employment status, or future career paths. Goals 3, 4, 6, and 9 are linked to this outcome.

5. Recognize ethical issues and devel-op a framework for apprdevel-opriate resolu-tions. Goals 4, 9, and 10 are linked to this outcome.

6. Apply information technology to business problems. Goals 3, 4, and 9 directly relate to this outcome.

7. Appreciate diverse perspectives and use them for mutual benefit. Goals 4, 6, 7, and 9 relate to this outcome.

8. Appreciate the importance of life-long learning as a means of enhancing their ability to add value to their employers’ endeavors and expand their

own career opportunities. Goals 3, 4, and 9 focus on this outcome.

From this point on, the FAIR process at the program level follows the same steps as at the college level. Should the mission of the college or the learning outcomes of the program change, the above reconciliation between mission statement and goals and between stu-dent learning outcomes and goals will readily highlight the impacted goals. The breakdown into single-focus goals will facilitate linking strategic intent with operational tasks at the faculty-development level.

Conclusion

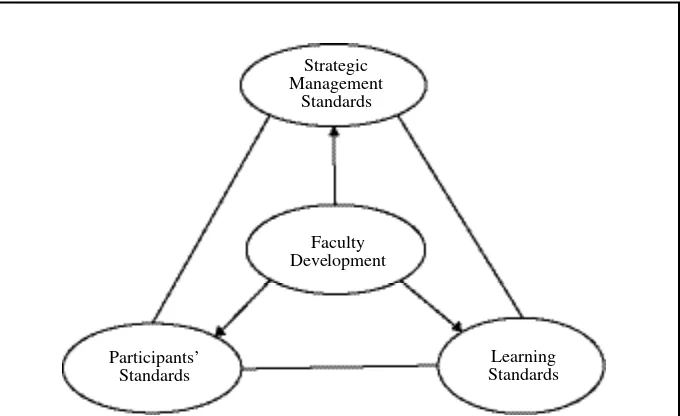

The proposed framework illustrated in Figure 1 places FDPs in a central role in the process of linking standards to the school’s mission. Figure 2 includes in the framework the inputs and outputs of the FAIR process.

The proposed framework presented in this article seeks solely to support and enable school leadership, not replace it. The greatest challenge facing leadership based on a school mission approach is that of creating a mission that is “com-pelling,” (i.e., the mission must be “clear,” and “vibrant and relevant,” AACSB, 2005).

Operationalizing the notion of mis-sion-driven processes is constrained by

Strategic Management

Standards

FIGURE 1. Faculty development as a central role in meeting Association to Advance Collegiate School of Business (AACSB) standards.

Faculty Development

Participants’ Standards

Learning Standards

the challenge of organizing myriad direc-tives. Alluring visions are essential in all organizations (Kouzes & Posner, 2003). This dual aspect of a properly developed school mission—alluring and com-pelling—ought to guide the development of FDPs and vice versa. Under the pro-posed framework, the school’s leadership decides what is important to it. Individual faculty members are then guided to develop their goals and to address their needs given where they are in their careers. Faculty mentors provide the crit-ical link and, as such, need to be empow-ered to represent the college. This approach will be successful to the extent that appropriate mentors are identified and supported. The merits of this approach are a function of how well this tool inspires the school leaders to create a compelling mission and an alluring FDP.

The perspective driving the changes in AACSB standards provides the leader-ship with an opportunity to align the val-ues of the business school with its prac-tices. The proposed tool capitalizes on this opportunity. It uses the faculty devel-opment plan as a means to operationalize mission-driven strategic initiatives while recognizing variances in individual devel-opment needs. The proposed formulation

provides a systematic, transparent, and flexible approach to the complex problem of configuring faculty development pro-grams to best meet the school’s mission.

NOTE

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Craig A. Kelley, Professor of Mar-keting and Sales Management, California State University, Sacramento, 6000 J St., Sacramento, CA 95819-6088.

E-mail: kelleyca@csus.edu

REFERENCES

Ackoff, R. L. (1981). Creating the corporate future. New York: Wiley.

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). (2005). AACSB Interna-tional. Retrieved February 4, 2005, from http://www.aacsb.edu/

Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. (2002). Building competitive advantage through people. MIT Sloan Management Review, 43(2), 34–41. Bland, C. J., & Schmitz, C. C. (1990). A guide to

the literature on faculty development. In J. H. Schuster & D.W. Wheeler (Eds.), Enhancing faculty careers: Strategies for development and renewal. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Blignaut, A. S., & Trollip, S. R. (2003).

Measur-ing faculty participation in asynchronous dis-cussion forums. Journal of Education for Busi-ness, 78,347–353.

California State University, Sacramento, College of Business Administration. (n.d.). CBA Mis-sion Statement. Retrieved February 4, 2005, http://www.cba.csus.edu/AboutCBA/mission Vision.asp

Davis, D. F., & McCarthy, T. M. (2005). The future of marketing scholarship: Recruiting for marketing doctoral programs. Journal of Mar-keting Education, 27(1), 14–25.

DiLorenzo, T. M., & Heppner, P. P. (1994). The role of an academic department in promoting faculty development: Recognizing diversity and leading to excellence. Journal of Counseling and Development, 72(5), 485–491.

Dolan, S. L., Garcia, S., & Auerbach, A. (2003). Understanding and managing chaos in organi-zations. International Journal of Management, 20(1), 23–35.

Festervand, T. A., & Tillery, K. R. (2001). Short-term study abroad programs: A professional development tool for international business fac-ulty. Journal of Education for Business, 77, 106–111.

Jantzen, R. H. (2000). AACSB mission-linked standards: Effects on the accreditation process. Journal of Education for Business, 75, 343–347.

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2003). The lead-ership challenge (3rd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Millis, B. J. (1994). Faculty development in the 1990s: What it is and why we can’t wait. Jour-nal of Counseling and Development, 72(5), 454–464.

Nathan, P. E. (1994). Who should do faculty development and what should it be? Journal of Counseling and Development, 72(5), 508–509. Pritchard, R. E., Potter, G. C., & Saccucci, M. S. (2004). The selection of a business major: Ele-ments influencing student choice and implica-tions for outcomes assessment. Journal of Edu-cation for Business, 79, 152–154.

Shisler, C. (1995). Faculty development: The per-sonal touch. Society of Research Administra-tors, 27(2), 31–34.

Smith, K. J., & Rubenson, G. C. (2005). An exploratory study of organizational structures and processes at AACSB member schools. Journal of Education for Business, 80, 133–139.

Smith, K. J., Rubenson, G. C., & Bebee, R. F. (2002). Using self-directed teams to achieve quality education: An illustrative matrix model for a business school structure. Journal of Edu-cation for Business, 77, 214–218.

Sorcinelli, M. D. (1992). The career development of pretenure faculty: An institutional study. Amherst: Center for Teaching, University of Massachusetts.

Sorcinelli, M. D. (1994). Effective approaches to new faculty development. Journal of Counsel-ing and Development, 72(5), 474–480. Weber, P. S., Weber, J. E., Sleeper, B. J., &

Schneider, K. C. (2004). Self-efficacy toward service, civic participation and the business stu-dent: Scale development and validation. Jour-nal of Business Ethics, 49(4), 359–370. Witcher, B. J. (2003). Policy management of

strat-egy (hoshin kanri). Strategic Change, 12(2), 83–94.

Yunker, P. J. (1998). A survey of business school heads on mission-linked AACSB accreditation standards. Journal of Education for Business, 73,137–143.

Benchmarking for Continuous Improvement Strategic

FIGURE 2. Linking school mission to learning and participants’ standards.

APPENDIX A

Implementation of the FAIR Process of Linking Faculty Development to the School Mission

FOCUS

1.1 Break mission statement into values.

1.2 Convert values into goals of the school.

1.3 Rank and rate the goals of the school per current strategic intent.

ALIGN

2.1. Make resources available.

2.2. Request proposals.

2.3. Provide a rubric based on the ranked and rated goals of the school.

INTEGRATE

3.1. Mentors provide support by reviewing and updating individual faculty development plans and by linking them with the strate-gic intent of the school.

3.2. Individual faculty members draft proposals.

3.3. School evaluates proposals and allocates resources in an open forum.

REVIEW

4.1. School evaluates allocation plan against the ranked and rated goals of the school in an open forum.

4.2. School surveys faculty satisfaction with the process and results.

4.3. School assesses faculty

APPENDIX B

College of Business Administration (CBA) Goals and Single-Action Goals

Goals

Goal 1: To improve percep-tion of the college by stu-dents, alumni, and regional organizations.

Goal 2: To graduate sought-after students.

Goal 3: To hire high quality faculty and to provide con-tinuous support for activities that serve to maintain cur-rency and academic qualifi-cations of faculty.

Goal 4: To engage in activi-ties that result in effective teaching, research, and ser-vice to the community.

Goal 5: To increase funding from organizations, alumni, and community members.

Goal 6: To increase faculty involvement with regional organizations, alumni, and community members.

Single-action goals

Goal 1a: To improve students’ perceptions of the CBA.

Goal 1b: To improve alumni’s perceptions of the CBA.

Goal 1c: To improve regional organizations’ percep-tions of the CBA.

Goal 2: To graduate sought-after students.

Goal 3a: To hire high quality faculty.

Goal 3b: To provide continuous support for activi-ties that serve to maintain currency of tenured facul-ty members.

Goal 3c: To provide continuous support for the activities that serve to maintain currency of proba-tionary faculty members.

Goal 4a: To engage in activities that result in effec-tive teaching.

Goal 4b: To engage in activities that result in effec-tive research.

Goal 4c: To engage in activities that result in effec-tive service.

Goal 5a: To increase funding from organizations. Goal 5b: To increase funding from alumni. Goal 5c: To increase funding from community lead-ers.

Goal 6a: To increase faculty involvement with regional organizations.

Goal 6b: To increase faculty involvement with alumni.

Goal 6c: To increase faculty involvement with com-munity leaders.

(appendix continues)

APPENDIX B—(Continued)

Goals

Goal 7: To increase collabo-rative curricular and research activities within the college.

Goal 8: To improve staff development and organiza-tion within the college.

Goal 9: To proactively incor-porate relevant regional, global, and technical changes to the curriculum.

Goal 10: To encourage stu-dents to engage in communi-ty activities to promote the welfare of others.

Single-action goals

Goal 7a: To increase collaborative curricular activi-ties within the college.

Goal 7b: To increase collaborative research activi-ties within the college.

Goal 8a: To improve staff development within the college.

Goal 8b: To improve organization within the col-lege.

Goal 9a: To proactively incorporate relevant region-al changes in the curricula.

Goal 9b: To proactively incorporate relevant global changes in the curricula.

Goal 9c: To proactively incorporate relevant techni-cal changes in the curricula.

Goal 10: To encourage students to engage in com-munity activities that promote the welfare of others.