Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji], [UNIVERSITAS MARITIM RAJA ALI HAJI Date: 12 January 2016, At: 17:54

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Teaching Business Students to Recognize a Firm

in Distress: What Information Is Important to

Experts?

Constance M. Lehmann & Carolyn Strand Norman

To cite this article: Constance M. Lehmann & Carolyn Strand Norman (2005) Teaching Business Students to Recognize a Firm in Distress: What Information Is Important to Experts?, Journal of Education for Business, 81:2, 91-95, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.81.2.91-98

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.81.2.91-98

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 17

View related articles

ABSTRACT.Business failures are the

result of many decisions within individual

companies—Can business students be taught

to recognize a firm that is in financial

dis-tress? If it can be known and understood how

professionals acquire expertise in evaluating

the financial health of a firm, then it follows

that structuring both the college classroom

experience and the corporate training

envi-ronment to enhance learning will be easier.

In this article, the authors investigated the

amount and types of information and tests

requested by professionals concerning a firm

in distress compared to those requested by

intermediates and novices. The authors found

that the amount and kinds of information and

tests requested by novices differed

signifi-cantly from that requested by experts in the

field. Based on the results, the authors make

recommendations to help business educators

better prepare business students to recognize

a firm in financial distress.

Copyright © 2005 Heldref Publications

n 2001, a record 257 publicly traded companies with combined assets of $258.8 billion filed for bankruptcy, and in 2002, WorldCom filed for bankruptcy with over $103 billion in assets (Venuti, 2004). While business failures are the result of many decisions within individ-ual companies, can we teach business students to recognize a firm that is in financial distress? The purpose of this article was to investigate the amount and types of information and tests requested by professionals concerning a firm in distress.

We believe this is an important topic for several reasons. First, if it can be known and understood how professionals acquire expertise in evaluating the finan-cial health of a firm, then it follows that structuring both the college classroom experience and the corporate training environment to enhance learning will be easier. Focusing on category knowledge, Bonner, Libby, and Nelson (1997) noted that understanding the particular aspects of knowledge that experts need or use to determine a company’s financial situa-tion is necessary before educators and firms can determine the best ways to organize future instruction.

Second, based on recent corporate accounting scandals, which led to a number of business failures, we believe that the going-concern determination should be a shared concern of the man-agement team, internal auditors, and the

external auditors. In addition, the going-concern decision should be viewed as an opportunity to develop junior and mid-level staff competencies in this vital area. By teaching business students methods to approach the going-concern evaluation in their classes, they will be better prepared to use these skills as entry-level managers and accountants.

Theory and Development of Hypotheses

Most research using the expert–novice paradigm examines the difference in per-formance between experts and novices. However, Willson (1990, 1994) suggest-ed that expertise development should be examined as a progression toward some level of competence and, therefore, stud-ied intermediate development (i.e., the process of becoming an expert). Medical researchers (e.g., Willson, 1994; Schmidt & Boshuizen, 1993a, 1993b; Van de Wiel, Boshuizen, & Schmidt, 2000) have identified common characteristics about different experience groups. Novices recall everything they know about a cer-tain topic with limited understanding of how the facts are related while interme-diates include a few high-level concepts and their interrelations as well as more attention to contextual factors. By con-trast, experts tend to filter information and focus on a few important facts or details.

Teaching Business Students to Recognize

a Firm in Distress: What Information Is

Important to Experts?

CONSTANCE M. LEHMANN CAROLYN STRAND NORMAN

UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON-CLEAR LAKE VIRGINIA COMMONWEALTH UNIVERSITY HOUSTON, TEXAS RICHMOND, VIRGINIA

I

When examining a going-concern task (e.g., determining whether a firm is in financial distress), experts must con-sider specific information to answer the question: Is there substantial doubt about the firm’s ability to continue as a going-concern for a reasonable period of time? We propose the idea that the diagnosis of a firm’s financial condition might be strikingly similar to a doctor’s diagnosis of a patient—each of these tasks requires the expert to examine specific information to make a decision. For example, medical experts identify common traits in the list of symptoms given by a patient. They quickly narrow the possible diagnosis by asking direct questions that focus on a specific, previ-ous experience with similar circum-stances and request only those tests nec-essary to confirm a specific diagnosis. Consequently, when asked to justify or explain a diagnosis, experts give a short, concise explanation identifying the information they used in their decision. Stevens, Lopo, and Wang (1996) asked medical teaching faculty and 2nd-year medical students to evaluate and diagnose six cases. The faculty and stu-dents could also access additional patient information and order additional tests to make their diagnoses. The results suggested that students request additional tests and information seldom ordered or used by experts. The number of additional tests requested averaged about 9 tests for the experts, compared to about 25 for the students who made the correct diagnoses.

Schmidt, Norman, and Boshuizen (1990) noted that experts gather less data rather than more data. They theo-rized that experts rapidly assess the case in front of them in terms of previous cases, then focus on the information they need to confirm their diagnoses. However, intermediates appear to progress step-by-step to diagnose a case. They require more information to clarify and confirm their diagnoses than experts do, and they often combine knowledge from the classroom with knowledge from patient encounters.

For over a decade, accounting researchers have been studying expertise as it relates to a going-concern task. Choo (1989) suggested that “expertise may be broadly defined as superior schemas (in

amount and organization) developed through a gradual process of abstracting domain-specific knowledge on the basis of experience” (p. 125). Abdolmoham-madi and Wright (1987) noted that experts gather less data than novices. In their structured task, experts chose a smaller sample of items to test than did students. Based on the foregoing discus-sion, we tested the following hypotheses: H1: Experts will request fewerfacts and tests regarding the case company’s finan-cial situation than intermediates will; intermediates will request fewerfacts and tests than novices will.

H2: Experts will request different infor-mation and tests regarding the case com-pany’s financial situation than intermedi-ates will; intermediintermedi-ates will request

different information and tests than novices will.

METHOD Participants

Independent auditors are typically considered the experts who are expected to opine on the financial health of a firm. Therefore, our sample consisted of accountants (73 accounting students from a large university in the Southwest and 56 accounting professionals from the Seattle area). Each of the students who participated in this study had completed a 3-month summer internship with a national public accounting firm. The pro-fessionals had varying levels of experi-ence. Following Willson’s (1990, 1994) suggestion, we partitioned our sample into three groups to examine the amount and types of information and tests requested by each group as they pon-dered a going-concern task. The partici-pants in our study were grouped as fol-lows: (a) Novices were 73 students who had completed a 3-month internship; (b) Intermediates were 41 accounting pro-fessionals with less than 72 months of professional experience; and (c) Experts were 15 accounting professionals with 72 or more months of professional expe-rience (senior managers or partners).

The Task

We developed a case based on data from an actual company (see Appendix for case materials). This case describes

the background particulars of the airline industry and contains fictitious financial data and other information typically found in a Management Discussion and Analysis (MD & A) portion of annual financial statements (the actual airline declared bankruptcy and is no longer in operation). The company had several problems, including negative cash flows from operations and industry pressures, with excessive leverage and capital com-mitments. The company was issued a going-concern qualification in their audit report for that year. In addition to sum-marizing the financial condition of the company, the participants were asked to do two things: List any information they would request to confirm their judgments and list any tests they would conduct to confirm their judgments.

Each participant completed the experiment in about 1 hour, and no time constraints were imposed. Students completed the experiment in a lab set-ting, while the professionals were visit-ed at their places of employment.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows the descriptive statis-tics by experience group. The mean number of months of professional expe-rience for the intermediate group was 23.9 (SD = 20.1); for the expert group the mean was nearly 14 years (SD = 99.0 months). The average age was 24 years (SD = 1.4) for those in the novice group, 27 years (SD = 5.1) for those in the intermediate group, and 42 years (SD = 8.5) for those in the expert group. Seventy-nine of the participants (61.2%) were female.

Tests of Hypotheses

Number of Information Items and Tests Requested

Table 1 also shows the total number of additional information items request-ed by the subjects, which rangrequest-ed from a minimum of zero items in the expert group to a maximum of 10 items in the novice group, with a mean of about 3.6 (SD = 2.0) for the novice group, 2.6 (SD

= 1.1) for the intermediate group, and 2.3 (SD= 1.8) for the expert group. The

total additional tests that the subjects said they would conduct ranged from a minimum of zero (across all groups) to a maximum of 8 (in the novice group). The mean for the novice group was about 2 (SD= 1.2), while the means for the intermediate and expert groups were 1.7 (SD = 5.1) and 1.1 (SD = 1.9), respectively.

We used regression analysis to test the first hypothesis because the direc-tion of the reladirec-tionship between the variables is more easily interpreted than the results of a simple ANOVA, which does not indicate the direction of the differences between groups. We per-formed t tests using the independent variable experience group. The results indicated that the number of additional information items requested decreases monotonically with experience, t (1, 127) = −3.454,p= .001. In other words, the expert group requested less informa-tion than the intermediate group, who requested less information than the novice group. The linear regression also indicated that experience is significant-ly and negativesignificant-ly related to the number of tests the participants would conduct,

t(1, 128) = −3.259,p= .001, suggesting that the expert group would conduct fewer tests than the intermediate group, who would conduct fewer tests than the novice group. The results were similar when we used number of months of pro-fessional experience as the independent variable. These results suggested sup-port for Hypothesis 1 and indicated that experts would request less additional information and conduct fewer addi-tional tests than the other two groups.

Type of Information Items and Tests Requested

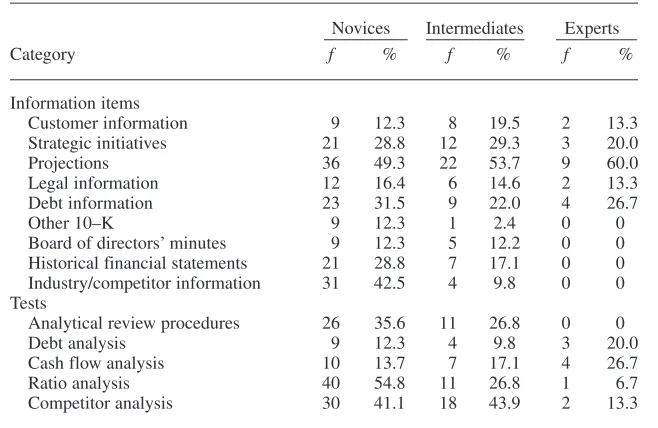

We categorized the information pro-vided in the participants’ written proto-cols to identify patterns in the types of information and tests requested by indi-viduals in the different experience groups. The following categories were mentioned frequently enough to ana-lyze: customer information, strategy information, financial or economic pro-jections, legal information, debt agree-ments, other 10K items (e.g., MD & A, notes to financial statements), board minutes, historical financial statements,

and industry or competitor information. Refer to Table 2 for the frequencies and percentages of each category for the three experience groups. We divided the additional tests that participants said they would conduct into five categories based on the subjects’ written protocols: analytical review procedures, debt analysis, cash flow analysis, ratio analy-sis, and competitor analysis. Table 2 also shows the frequencies and percent-ages of each category of tests requested by the three experience groups.

All groups requested financial projec-tions, board of directors’ minutes, cus-tomer information, strategic initiatives information, debt agreements, and legal information, and the groups indicated they would perform cash flow analysis and debt analysis in numbers close to the expected frequencies. Experts indi-cated that they would request financial projections more frequently than novices. Of the novices, 54.8% said they would perform ratio analysis, while only 6.7% of the experts indicat-ed that they would perform this test. None of the experts stated that they would perform analytical review proce-dures, but they indicated that they would perform a cash flow analysis twice as often as novices.

TABLE 1. Descriptive Statistics for Variables, by Experience Group

Experience Age Information Tests (months) (years) requesteda requestedb

Experience group M SD M SD M SD M SD

Novices 2.8 0.5 23.7 1.4 3.6 2.0 2.1 1.2 Intermediates 23.9 20.1 27.2 5.1 2.6 1.1 1.7 5.1 Experts 159.4 99.0 42.4 8.5 2.3 1.8 1.1 1.9

Note. n= 73 for Novices (47 women, 26 men); n= 41 for Intermediates (26 women, 15 men); and

n= 15 for Experts (6 women, 9 men).

aThe ranges of additional information items requested were 1–10 for Novices, 1–5 for

Inter-mediates, and 0–5 for Experts. bThe ranges of additional tests requested were 0–8 for Novices, 0–4

for Intermediates, and 0–3 for Experts.

TABLE 2. Frequency and Percentages of Information Items and Tests Requested, by Experience Group

Novices Intermediates Experts

Category f % f % f %

Information items

Customer information 9 12.3 8 19.5 2 13.3 Strategic initiatives 21 28.8 12 29.3 3 20.0

Projections 36 49.3 22 53.7 9 60.0

Legal information 12 16.4 6 14.6 2 13.3 Debt information 23 31.5 9 22.0 4 26.7

Other 10–K 9 12.3 1 2.4 0 0

Board of directors’ minutes 9 12.3 5 12.2 0 0 Historical financial statements 21 28.8 7 17.1 0 0 Industry/competitor information 31 42.5 4 9.8 0 0 Tests

Analytical review procedures 26 35.6 11 26.8 0 0

Debt analysis 9 12.3 4 9.8 3 20.0

Cash flow analysis 10 13.7 7 17.1 4 26.7

Ratio analysis 40 54.8 11 26.8 1 6.7

Competitor analysis 30 41.1 18 43.9 2 13.3

Note. Percentages indicate the percentage of an entire group that requested a given category of information or test.

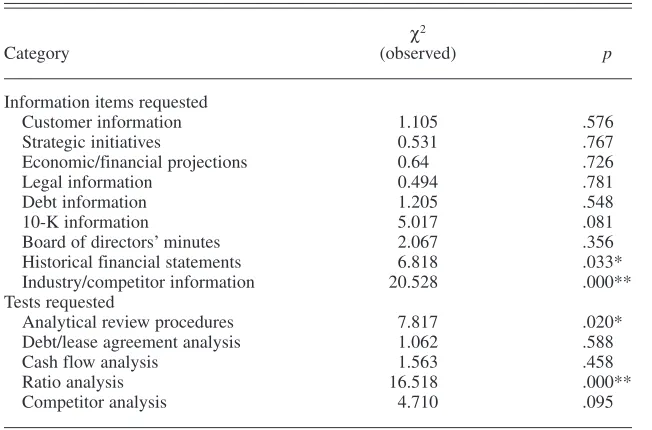

To test whether the observed frequen-cies of the types of information items and tests requested differed significantly from the expected frequencies, we per-formed chi-square tests for each of the information and test categories. To explain, we compared the observed fre-quency (actual number of participants who requested the given information item or test) to the expected frequency for each experience group (number of participants in a given group/total num-ber of subjects in the sample). The results, reported in Table 3, suggested that the observed frequencies signifi-cantly (p < 0.05) differed from the expected frequencies in requests for the following: (a) historical financial state-ments, (b) industry or competitor infor-mation, (c) analytical review proce-dures, and (d) ratio analysis.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether experience is relat-ed to the number and types of addition-al information and tests requested to support an assessment of a company’s financial health. In our study, the experts appeared to have a more focused view of what information and tests

would be needed to confirm their “diag-noses” of the case company’s financial health, requesting less additional infor-mation and fewer tests to confirm their judgments. These results are consistent with earlier studies in the medical and accounting literature (Abdolmohamma-di & Wright, 1987; Schmidt et al., 1990; Stevens et al., 1996).

Our results suggest that experts request less information and fewer tests to confirm judgments than do interme-diate-level personnel. Likewise, inter-mediates request less information and fewer tests than do novices. Further-more, the type of information requested differs significantly among the groups. The information that experts considered most necessary or useful to confirm their decisions about the case compa-ny’s financial condition was financial projections and the tests most identified as useful were cash flow analysis and debt analysis. At the other extreme, novices most frequently requested his-torical financial statements and com-petitor information. The tests of interest to novices were ratio analysis (both for the case company and its industry or competitors) and other analytical review procedures. In other words, the informa-tion and tests that were most used by

experts in our sample were dissimilar to those selected by the novices. Statisti-cally significant differences due to experience level were found in the requests for industry or competitor information, historical financial state-ments, ratio analysis, and analytical review procedures. These differences between experience groups may have important implications for university-level instruction of business students, as well as training for managers and accountants in business.

Educators typically follow recom-mendations in textbooks regarding information that should be useful to evaluate a firm’s financial condition. The choices of information and tests requested by the novices in our study to analyze the company’s financial condi-tion are consistent with what is recom-mended in textbooks (Arens, Elder, & Beasley, 2005). The results of our study suggest that experienced professionals requested very different pieces of infor-mation and tests than did the students. Based on our results, business profes-sors may wish to modify or supplement the instructional block that covers finan-cial analyses of companies. Further-more, instructors might wish to incorpo-rate using cash flow and debt analyses into more exercises designed to deter-mine a firm’s health. Professors might also demonstrate how financial projec-tions can be used in the going-concern evaluation to enhance judgment.

By supplementing traditional instruc-tional material with the methods used by experienced professionals in deci-sion making, instructors should afford their students a better understanding of the factors that are considered important by professionals. Augmenting class-room instruction with the results of this study might also enhance critical think-ing skills to shorten the learnthink-ing curve for gaining expertise in diagnosing the financial condition of a firm. This infor-mation should be equally helpful to managers and accountants in organiza-tions that want to efficiently and effec-tively train entry-level personnel. Our results may also be useful to firms that wish to develop decision aids as a method of training professionals at all levels to effectively evaluate an organi-zation’s financial condition.

TABLE 3. Chi-Square Tests for Information Items and Tests Requested, by Category

χ2

Category (observed) p

Information items requested

Customer information 1.105 .576

Strategic initiatives 0.531 .767

Economic/financial projections 0.64 .726

Legal information 0.494 .781

Debt information 1.205 .548

10-K information 5.017 .081

Board of directors’ minutes 2.067 .356 Historical financial statements 6.818 .033* Industry/competitor information 20.528 .000** Tests requested

Analytical review procedures 7.817 .020* Debt/lease agreement analysis 1.062 .588

Cash flow analysis 1.563 .458

Ratio analysis 16.518 .000**

Competitor analysis 4.710 .095

Note. Significant ps indicate that the observed frequency of requests for a particular information item or test differed significantly from the expected frequency.

*p≤ .05. **p≤ .001.

NOTE

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Constance M. Lehmann, School of Business & Public Administration, University of Houston–Clear Lake, 2700 Bay Area Boule-vard, Suite 3-237, Houston, Texas 77058. E-mail: lehmann@cl.uh.edu.

REFERENCES

Abdolmohammadi, M., & Wright, A. (1987). An examination of the effects of experience and task complexity on audit judgments. The Accounting Review, 62(1), 1–13.

Arens, A., Elder, R., & Beasley, M. (2005). Audit-ing and assurance services: An integrated approach (10th Ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bonner, S., Libby, R., & Nelson, M. (1997). Audit

category knowledge as a precondition to learn-ing from experience. Accounting, Organiza-tions, and Society,22(5), 387–410.

Choo, F. (1989). Cognitive scripts in auditing and accounting behavior. Accounting, Organiza-tions, and Society,14(5/6), 481–493. Schmidt, H. G., & Boshuizen, H. P. A. (1993a).

On acquiring expertise in medicine. Education-al Psychology Review,5(3), 205–221. Schmidt, H. G., & Boshuizen, H. P. A. (1993b).

On the origin of intermediate effects in clinical case recall. Memory and Cognition, 21(3), 338–351.

Schmidt, H. G., Norman, G. R., & Boshuizen, H. P. A. (1990). A cognitive perspective on med-ical expertise. Academic Medicine, 65(10), 611–621.

Stevens, R. H., Lopo, A. C., & Wang, P. (1996). Artificial neural networks can distinguish novice and expert strategies during complex problem-solving. Journal of the American

Med-ical Informatics Association,3(2), 131–138. Van de Wiel, M. J. W. P., Boshuizen, H. P. A., &

Schmidt, H. G. (2000). Knowledge restructur-ing in expertise development: Evidence from pathophysiological representations of clinical cases by students and physicians. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 12(3), 323–355.

Venuti, E. (2004, May). The going-concern assumption revisited: Assessing a company’s future viability. CPA Journal,74(5), 40–43. Willson, V. L. (1990). Methodological limitations

for the use of expert systems techniques in sci-ence education. Journal of Research in Science Teaching,27(1), 69–77.

Willson, V. L. (1994). Research methods for investigating problem-solving in science educa-tion. In D.R. LaVoie (Ed.),Towards a cognitive science perspective for scientific problem solv-ing. pp. 264–294. Washington, DC: National Association for Research in Science Teaching.