DOI: 10.1542/peds.2009-0165

2009;124;e1149-e1152; originally published online Nov 23, 2009;

Pediatrics

http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/124/6/e1149

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Energy Expenditure for Breastfeeding and

Bottle-Feeding Preterm Infants

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: Most VLBW infants cannot be fed at the breast at birth, and feeding with expressed breast milk through a gastric tube is recommended. Sucking skills mature at ⬃34 weeks, when nipple-feeding is introduced.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS: REE measurements for preterm infants immediately after feeding at the breast and after feeding of expressed breast milk by bottle are very similar.

abstract

OBJECTIVE:We hypothesized that resting energy expenditure (REE) would be higher after breastfeeding than after bottle-feeding.

METHODS:Nineteen preterm infants (gestational age: 32 weeks) in stable condition who were nourished entirely with their mothers’ breast milk were assigned randomly to feeding either by bottle or at the breast. Each infant served as his or her own control subject. REE was measured for 20 minutes after feeding. Breast milk quantity was evaluated with prefeeding and postfeeding weighing. REE values for bottle-feeding and breastfeeding were compared with pairedttests.

RESULTS:Contrary to our null hypothesis, the group’s mean REE val-ues after bottle-feeding and breastfeeding were very similar (284.7⫾ 26.8 kJ/kg per day [68.3⫾6.4 kcal/kg per day] vs 282.6⫾28.5 kJ/kg per day [67.5⫾6.8 kcal/kg per day]; not significant). The duration of feeding was significantly longer for breastfeeding than for bottle-feeding (20.1⫾7.9 vs 7.8⫾2.9 minutes;P⬍.0001).

CONCLUSION:There was no significant difference in REE when infants were breastfed versus bottle-fed. Longer feeding times at the breast did not increase REE. We speculate that it is safe to recommend feeding at the breast for infants born at⬎32 weeks when they can tolerate oral feeding.Pediatrics2009;124:e1149–e1152

AUTHORS:Irit Berger, MD, Valentin Weintraub, PhD, Shaul Dollberg, MD, Rozalia Kopolovitz, RN, and Dror Mandel, MD

Department of Neonatology, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv, Israel

KEY WORDS

metabolic rate, indirect calorimetry, oral feeding

ABBREVIATIONS

REE—resting energy expenditure VLBW—very low birth weight

This trial has been registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT00838188).

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2009-0165

doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0165

Accepted for publication Jun 23, 2009

Address correspondence to Shaul Dollberg, MD, Department of Neonatology, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, 6 Weizman St, Tel Aviv 64239, Israel. E-mail: [email protected]

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright © 2009 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE:The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

logic advantages for general health, growth, and development and possibly the enhancement of cognitive develop-ment, is the optimal method of infant feeding.1–4 Human milk conveys

spe-cific advantages in improved host de-fense,5–7suitability for gut absorption,

morapid gastric emptying, and re-duced risk of necrotizing enterocoli-tis8,9for very low birth weight (VLBW)

infants. Psychological and developmen-tal benefits also have been reported,10,11

and there are even a number of studies that indicate potential health benefits for breastfeeding mothers.12–14

Most VLBW infants cannot be fed at the breast at birth, and feeding with expressed breast milk through a gas-tric tube is recommended. Sucking skills mature at ⬃34 weeks, when nipple-feeding is introduced.15–18In the absence

of evidence-based data to determine the best time to introduce breastfeeding, many clinicians use empiric criteria, such as the infant’s weight, gestational age, and ability to bottle-feed, as prox-ies of readiness to breastfeed. Despite some evidence of physiologic benefits of preterm infants feeding at the breast, many neonatologists consider direct breastfeeding to be too fatiguing for preterm infants. It is not known, how-ever, whether preterm infants who are breastfed expend more energy than bottle-fed infants.19–22

The primary goal of this study was to compare resting energy expenditure (REE) for preterm infants fed their moth-ers’ expressed milk by bottle or fed at the breast. We hypothesized that the REE would be higher with breastfeeding than with bottle-feeding.

METHODS

Study Population

Our institutional review board and the national Ministry of Health approved this study, and signed informed

con-were born atⱖ32 weeks of gestation and had reached the corrected gesta-tional age of ⱖ34 weeks were in-cluded. Infants in thermally stable con-dition were cared for in open unwarmed bassinets and were held by their moth-ers during feeding. The infants were all fed solely with their mothers’ breast milk starting during the first week of life, equivalent toⱖ150 mL/kg per day divided into 8 meals, and were growing steadily. They were considered ready to be recruited into the study when they could feed ⱖ1 full meal at the breast. Estimation of the amount of milk ingested was performed by test-weighing or by measuring the volume received by bottle. Infants who fed⬍25 mL from either bottle or breast, in-fants who required supplemental ox-ygen for ⱖ1 week before recruit-ment, infants diagnosed as having active infections, and infants with a patent ductus arteriosus were ex-cluded. We also excluded infants with congenital anomalies and infants who had either⬎5 daily episodes of apnea of prematurity or any apnea requiring assistance or methylxan-thine therapy.

Study Design

This was a prospective, randomized in-vestigation. Each infant was evaluated twice on a single day at 2 consecutive meals, once after breastfeeding and once after bottle-feeding of breast milk by using a premature nipple and ring (Ross Products Division, Columbus OH). In this way, each infant served as his or her own control subject. REE was re-corded for 20 minutes after each meal. The duration of each meal and the creamatocrit of the bottle, and at the beginning and the end of every feeding at the breast were measured as de-scribed previously.23,24

formed through indirect calorimetry. They were conducted while the infants were prone and asleep, by using a Del-tatrac II metabolic monitor (Datex-Ohmeda, Helsinki, Finland). The instru-ment uses the principle of an open circuit system that allows continuous measurements of oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production.25The

values are determined with the Fick principle, in which gas production or consumption⫽(concentration differ-ence in inspired and expired gas)⫻ total gas flow. This method is safe and allows prolonged measurements while allowing reasonable access to the in-fant for routine care.26Validation

stud-ies have shown the technique to give results equivalent to direct measure-ments.27 The instrument has an

in-traassay coefficient of variation of 3% in our hands, and it has been used ex-tensively for small infants by other investigators.28,29

Statistical Analysis

We used computer-generated random numbers in sealed opaque envelopes to assign the breast/bottle sequence. Statistical analysis of REE values with breastfeeding and bottle-feeding was performed with the pairedttest and regression analysis. Results are ex-pressed as mean⫾SD.Pvalues of .05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

mea-surement in the milk given by bottle (6.7 ⫾ 1.4%) was similar to the averaged creamatocrit values of the initial and fi-nal breast milk samples (6.1⫾1.4%;P⫽

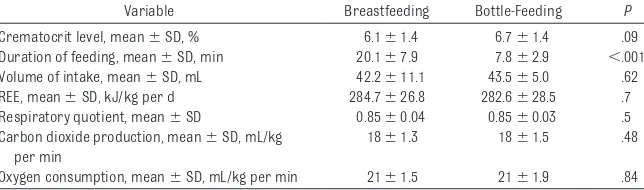

.09). Infants spent significantly more time at the breast (20.1⫾7.9 minutes) than when fed by bottle (7.8⫾2.9 min-utes;P⬍.0001). There were no signifi-cant differences in the volume of milk consumed through breastfeeding ver-sus bottle-feeding (42⫾11.1 vs 43.56⫾ 5.0 mL;P⫽.62) or in REE per volume of milk intake (6.8⫾2.4 vs 0.5⫾5.7 kJ/kg/ ml/d;P⫽.23). Contrary to our null hy-pothesis, there was no significant differ-ence in REE after direct breastfeeding versus bottle-feeding (284.7 ⫾ 26.8 kJ/kg per day [68.3 ⫾6.4 kcal/kg per day] vs 282.6⫾28.5 kJ/kg per day [67.5 ⫾6.8 kcal/kg per day];P⫽.7) (Table 1). Moreover, we could not find any consis-tent trends, because 5 infants had higher REE values after breastfeeding than after bottle-feeding, whereas the others showed a reverse pattern. The re-sults of regression analysis with the difference in REE with bottle-feeding ver-sus breastfeeding as the dependent vari-able and the duration of feeding as the independent variable were not signifi-cant (P⫽.8). We also found no correla-tions between the difference in REE with breastfeeding versus bottle-feeding and gestational age, chronologic age, birth weight, or weight at the time of exami-nation. The difference in the volume of milk ingested through breastfeeding versus bottle-feeding did not exceed 5 mL for any of the infants.

In addition, we demonstrated very simi-lar REE values immediately after feeding for our 20 preterm study infants fed breast milk directly at the breast or ex-pressed into a bottle, and longer feeding time at the breast did not increase REE. We would have needed⬃1300 infants to detect a significant difference if one ex-isted (P⫽.05; power⫽0.8).

DISCUSSION

Preterm infants lack the physiologic maturity for effective suck-swallow un-til they reach the corrected gestational age of⬃34 weeks.15–19At that time, the

introduction of oral feedings depends on a learning process on the part of the preterm infant. Introduction of small quantities and increases to full oral feedings may take days or even weeks. The optimal timing of the first breastfeeding opportunity for preterm infants has not been studied systemat-ically. Clinicians have used empiric criteria, such as infant weight, gesta-tional age, and ability to bottle-feed, as indicators of readiness to breast-feed.19–21Introduction of bottle-feeding

before breastfeeding had been com-mon practice acom-mong neonatologists30

and may afford, among other factors, the ability to measure the exact volume of each meal, the ability to feed infants without transferring them from the in-cubator, and the ability to put into practice the notion that nurses with expertise may achieve better success in reaching full oral feeding faster. A study by Meier20 showed that small

preterm infants at corrected gestational age of 35 weeks had improved physio-logic responses with breastfeeding than with bottle-feeding, in terms of higher oxygen saturation, higher body tem-perature, and fewer desaturation events. It is also widely accepted that mothers of preterm infants stop lacta-tion earlier than do mothers of term infants.31Earlier feeding at the breast

would potentially extend the duration of breastfeeding for these mothers. Another potential concern may be nip-ple confusion, which has been re-ported mostly for term infants32 but

also for preterm infants.33

We studied preterm infants who were gavage-fed their own mother’s milk or preterm infant formula, and we found significantly lower REE values during breast milk feeding.29 This finding

strongly supports the use of breast milk rather than preterm formula, from an energy balance point of view. Whether there is any difference in REE between feeding of breast milk directly at the breast or by bottle has not been studied before. The fact that the me-chanics of sucking and swallowing at the breast are significantly different from those with artificial nipples, as demonstrated with ultrasonography,34

and the longer duration of feeding at the breast led us to hypothesize that REE values also would be different. De-spite these other distinct differences, we found that REE values were very similar with the 2 methods of feeding.

One potential limitation of our study is the timing of the measurement of REE. We studied infants immediately after feeding, because measurements during breastfeeding were not technically pos-sible. From our previous study, we knew that the REE increases from baseline to the time of gavage feeding and further increases during the immediate post-prandial period.29We measured the REE

in the current study immediately after feeding because we expected that the

TABLE 1 REE and Clinical and Laboratory Outcomes for Infants Who Were Breastfed or Bottle-Fed Their Mother’s Milk

Variable Breastfeeding Bottle-Feeding P Crematocrit level, mean⫾SD, % 6.1⫾1.4 6.7⫾1.4 .09 Duration of feeding, mean⫾SD, min 20.1⫾7.9 7.8⫾2.9 ⬍.001 Volume of intake, mean⫾SD, mL 42.2⫾11.1 43.5⫾5.0 .62 REE, mean⫾SD, kJ/kg per d 284.7⫾26.8 282.6⫾28.5 .7 Respiratory quotient, mean⫾SD 0.85⫾0.04 0.85⫾0.03 .5 Carbon dioxide production, mean⫾SD, mL/kg

per min

18⫾1.3 18⫾1.5 .48

Oxygen consumption, mean⫾SD, mL/kg per min 21⫾1.5 21⫾1.9 .84

higher REE values in the immediate postprandial period. Our study in-cluded periods of nonnutritive sucking for both modes of feeding. We do not know the relative contributions of nu-tritive and nonnunu-tritive sucking to REE.

for preterm infants immediately af-ter feeding at the breast and afaf-ter feeding of expressed breast milk by bottle are very similar. We speculate that allowing infants to feed at the breast as soon as they can tolerate

fold nutritional, physiologic, and emotional benefits.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Esther Eshkol is thanked for her edito-rial assistance.

REFERENCES

1. American Academy of Pediatrics, Work Group on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk.Pediatrics.1997; 100(6):1035–1039

2. Schanler RJ. Evaluation of the evidence to support current recommendations to meet the needs of premature infants: the role of human milk.Am J Clin Nutr.2007;85(2): 625S– 628S

3. Schanler RJ. The use of human milk for pre-mature infants.Pediatr Clin North Am.2001; 48(1):207–219

4. Schanler RJ, Shulman RJ, Lau C. Feeding strategies for premature infants: beneficial outcomes of feeding fortified human milk versus preterm formula.Pediatrics.1999; 103(6):1150 –1157

5. Howie PW, Forsyth JS, Ogston SA, Clark A, Florey CD. Protective effect of breast feed-ing against infection.BMJ.1990;300(6716): 11–16

6. Dewey KG, Heinig MJ, Nommsen-Rivers LA. Differences in morbidity between breast-fed and formula-breast-fed infants.J Pediatr.1995; 126(5):696 –702

7. Furman L, Taylor G, Minich N, Hack M. The effect of maternal milk on neonatal morbid-ity of very low birth weight infants.Arch Pe-diatr Adolesc Med.2003;157(1):66 –71 8. Valentine CJ, Hurst NM, Schanler RJ.

Hind-milk improves weight gain in low birth weight infants fed human milk.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.1994;18(4):474 – 477 9. Dvorak B, Halpern MD, Holubec H, et al.

Ma-ternal milk reduces severity of necrotizing enterocolitis and increases intestinal IL-10 in a neonatal rat model.Pediatr Res.2003; 53(3):426 – 433

10. Lucas A, Morley R, Cole TJ, Gore SM. A ran-domized multicentre study of human milk versus formula and later development in preterm infants.Arch Dis Child Fetal Neona-tal Ed.1994;70(2):F141–F146

11. Eidelman AI, Feldman R. Positive effect of human milk on neurobehavioral and cogni-tive development of premature infants.Adv Exp Med Biol.2004;554:359 –364

12. Furman L, Minich N, Hack M. Correlates of

lac-tation in mothers of very low birth weight in-fants.Pediatrics.2002;109(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/109/4/ e57

13. Aguayo J. Maternal lactation for preterm newborn infants. Early Hum Dev. 2001; 65(suppl):S19 –S29

14. Meier P, Brown LP. State of the science: breastfeeding for mothers and low birth weight infants.Nurs Clin North Am.1996; 31(2):351–365

15. Cooke RJ, Embleton ND. Feeding issues in preterm infants.Arch Dis Child Fetal Neona-tal Ed.2000;83(3):F215–F218

16. Gewolb IH, Schwietzer-Kenney EL, Taciak VL, Bosma JF. Developmental patterns of rhyth-mic suck and swallow in preterm infants. Dev Med Child Neurol.2001;43(1):22–27 17. Mizuno K, Ueka A. The maturation and

coor-dination of sucking, swallowing, and respi-ration in preterm infants.J Pediatr.2003; 142(1):36 – 40

18. Lau C, Smith EO, Schanler RJ. Coordination of suck-swallow and swallow-respiration in preterm infants.Acta Paediatr.2003;92(6): 721–727

19. Meier P, Anderson GC. Responses of small preterm infants to bottle- and breast-feeding.MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs.1987; 12:97–105

20. Meier P. Bottle- and breastfeeding: effects of transcutaneous oxygen pressure and temperature in preterm infants.Nurs Res. 1988;37(1):36 – 41

21. Chen CH, Wang TM, Chang HM, Chi CS. The effect of breast- and bottle-feeding on oxy-gen saturation and body temperature in preterm infants. J Hum Lact. 2000;16(1): 21–27

22. Bier JB, Ferguson A, Anderson L, et al. Breast-feeding of very low birth weight in-fants.J Pediatr.1993;123(5):773–778 23. Lucas A, Gibbs JA, Lyster RL, Baum JD.

Creamatocrit: simple clinical technique for estimating fat concentration and energy value of human milk. Br Med J. 1978; 1(6119):1018 –1020

24. Meier PP, Engstrom JL, Murtaugh MA, Vasan

U, Meier WA, Schanler RJ. Mothers’ milk feedings in the neonatal intensive care unit: accuracy of the creamatocrit technique. J Perinatol.2002;22(8):646 – 649

25. Je´quier E, Felber J. Indirect calorimetry. Ballieres Clin Endocrinol Metab.1987;1(4): 911–935

26. Bauer K, Pasel K, Uhrig C, Sperling P, Ver-smold H. Comparison of face mask, head hood, and canopy for breath sampling of flow through indirect calorimetry to mea-sure oxygen consumption and carbon monoxide production of preterm infants less than 1500 grams.Pediatr Res.1997; 41(1):139 –144

27. Olhager E, Forsum E. Total energy expendi-ture, body composition and weight gain in moderately preterm and full-term infants at term postconceptional age.Acta Paediatr. 2003;92(11):1327–1334

28. Lubetzky R, Vaisman N, Mimouni FB, Doll-berg S. Energy expenditure in human milk-versus formula-fed preterm infants.J Pedi-atr.2003;143(6):750 –753

29. Bauer K, Laurenz M, Ketteler J, Versmold H. Longitudinal study of energy expenditure in preterm neonates⬍30 weeks’ gestation during the first three postnatal weeks.J Pe-diatr.2003;142(4):390 –396

30. Sheppard JJ, Fletcher KR. Evidence-based interventions for breast and bottle feeding in the neonatal intensive care unit.Semin Speech Lang.2007;28(3):204 –212 31. Lefebvre F, Ducharme M. Incidence and

du-ration of lactation and lactational perfor-mance among mothers of low-birth-weight and term infants. CMAJ. 1989;140(10): 1159 –1164

32. Neifert M, Lawrence R, Seacat J. Nipple confusion: toward a formal definition.J Pe-diatr.1995;126(6):S125–S129

33. Nye C. Transitioning premature infants from gavage to breast.Neonatal Netw.2008; 27(1):7–13

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2009-0165

2009;124;e1149-e1152; originally published online Nov 23, 2009;

Pediatrics

Irit Berger, Valentin Weintraub, Shaul Dollberg, Rozalia Kopolovitz and Dror Mandel

Energy Expenditure for Breastfeeding and Bottle-Feeding Preterm Infants

& Services

Updated Information

http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/124/6/e1149

including high-resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/124/6/e1149#BIBL

at:

This article cites 33 articles, 10 of which you can access for free

Citations

cles

http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/124/6/e1149#otherarti

This article has been cited by 1 HighWire-hosted articles:

Subspecialty Collections

m

http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/collection/nutrition_and_metabolis Nutrition & Metabolism

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.pediatrics.org/misc/Permissions.shtml

tables) or in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures,

Reprints

http://www.pediatrics.org/misc/reprints.shtml