1

The Allocation of Responsibility between CEO and CFO for Financial Misreporting: Implications for Earnings Quality

Viktoria Diser

LMU Munich

Ulrich Schäfer

University of Zurich

Preliminary Version

May 31, 2017

Abstract. Even though financial reporting primarily falls within the scope of the CFO responsibilities, there is considerable evidence for the CEO’s influence on corporate misreporting. Regulatory initiatives such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 have therefore increased the CEO’s responsibility in the preparation of financial statements and made CEOs partially accountable for misreporting by their subordinates. We analyze the allocation of responsibility between the CEO and the CFO in a theoretical model and highlight their implications for earnings quality. While increasing the CFO’s responsibility generally improves earnings quality, assigning higher responsibility to the CEO may have detrimental effects. Our results show that higher CEO responsibility is particularly beneficial if the CEO has superior information about the CFO’s (financial and non-financial) reporting objectives. Furthermore, the responsibilities of the CEO and the CFO are substitutive regulatory instruments: Regulators should only increase CEO responsibility if CFOs cannot be held responsible for their own misreporting decisions.

2

1. Introduction

In an attempt to deter management fraud, the SEC passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, Section 302, “Corporate Responsibility for Financial Reports”, that requires the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) and the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) to certify the appropriateness of the financial statements and holds the top executives personally responsible for misrepresenting the operations and financial conditions of the company. Since financial reporting primarily falls within the scope of the CFO responsibilities, the certifications required by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 force CEOs to take a more active role in the financial reporting process and assume responsibility for preparing financial statements (Chang et al. 2006; Geiger & Taylor 2003). This study investigates the effects of increasing the CEO’s and the CFO’s accountability on earnings quality in a financial market setting. In particular, we assume that the CEO may be held accountable for the CFO’s misreporting and consider the benefits and downsides of increasing the CEO’s responsibility for the reporting bias introduced by the CFO.

CFOs are formally in charge of the financial reporting process. It is therefore not surprising that they exercise influence on the earnings report and should be held responsible for corporate misreporting (e.g., Geiger & North 2006; Jiang et al. 2010; Dichev et al. 2013). Interestingly, abundant literature on earnings management investigates the link between financial misreporting and CEOs’ incentives to misrepresent earnings (e.g., Burns & Kedia 2006). Given CEOs’ distinctive position in corporate control and their extensive decision rights, they can arguably prevent misreporting or foster earnings management by imposing pressure on CFOs even if CFOs are personally responsible for the reliability of financials reports (e.g., Feng et al. 2011; Dikolli et al. 2016).

Section 302 and find preliminary evidence that the certification requirement positively influences the market value of complying firms.1 However, opponents of the certification

requirement argue that the regulation imposed an unreasonable liability on CEOs. In a provocative article in Capital Magazine, Don Luskin, the Chief Investment Officer at Trend Macrolytics, claims that the CEO “could still be found guilty of a felony even though he acted

in utter innocence and good faith” (Luskin 2004).

This anecdotal and empirical evidence raises the question how the responsibility for financial reporting bias should be allocated between the CFO and the CEO. Yet, contemporaneous theory is silent on the effect of making the CEO accountable for the CFO’s reporting bias. We investigate the effects of the CFO’s and the CEO’s responsibility for financial reporting bias in a hierarchical reporting setting where the firm’s CFO prepares an earnings report and the CEO then provides the report to the market. The CFO and the CEO may sequentially engage in biasing the report. The uncertainty about the incentives and the actual biasing costs of the executives prevents the market from perfectly inferring the reporting bias.

In this setting, it seems likely that increasing the responsibility of the CFO and the CEO for the CFO’s reporting bias would reduce earnings management and increase the quality of reporting earnings. In fact, we find that increasing the CFO’s responsibility for biasing the financial report deters him from engaging in earnings management activities and positively influences earnings quality. However, contrary to the expectation, we show that increasing the CEO’s responsibility for the CFO’s biasing does not necessarily imply a higher quality of reported earnings. Rather, making the CEO accountable for the CFO’s reporting bias has two opposing effects. On the one hand, if the CEO is held accountable for the CFO’s misstatement of earnings, the CEO has an incentive to challenge the CFO’s report and (partially) reverse the introduced bias. On the other hand, the CEO’s cost of adjusting the report is unknown which introduces additional noise to the reported earnings, thereby reducing earnings quality. Whether the overall effect of the CEO’s responsibility on earnings quality is positive or negative depends on the CFO’s and CEO’s incentives to bias earnings and on the market’s uncertainty about the executives’ incentives and the costs of biasing. In particular, the earnings quality is likely to increase in the CEO’s responsibility for the CFO’s reporting bias if the CFO’s cost of biasing and his responsibility for the reporting bias are low, if the market’s

uncertainty about the CFO’s incentives is high and if the uncertainty about the CEO’s actual cost of biasing is low.

Our analysis is related to two strands of literature. First, we build on studies that investigate earnings management in a financial market setting. In a steady-state learning model where investors are perfectly informed about managerial reporting objectives, Stein (1989) shows that reporting bias is rationally anticipated by investors. As a consequence, earnings management decreases the welfare, but does not affect the information content of earnings. This result collapses if the market is uninformed about the manager’s reporting objectives. Fischer and Verrecchia (2000) and Dye and Sridhar (2004) introduce exogenous noise that prevents the market from fully recovering the reporting bias. Fischer and Verrecchia (2000) assume that investors have incomplete information about the (financial and non-financial) incentives of the management. Dye and Sridhar (2004) consider uncertainty about the manager’s private biasing costs.

Both models have been extensively used in the earnings management literature. For instance, Sankar and Subramanyam (2001) as well as Ewert and Wagenhofer (2005) extend the analysis to a two-period reporting framework with accrual reversals. Heinle and Verrecchia (2016) analyze firm’s decision whether to disclose and to bias information in the presence of other firms who may also release potentially biased reports.

There are few studies which consider financial reporting as multi-stage process. Dye and Sridhar (2004) study the interaction between the firm’s accountant and the manager. The role of the accountant is limited to aggregating subjective information elicited from the firm’s manager and objective information. Caskey et al. (2010) consider a two-stage reporting game similar to ours. The manager of a firm provides a potentially biased preliminary report to the firm’s audit committee. The audit committee is able to correct the report based on its own private information about fundamentals.

We add to this strand of literature in the following ways. First, we explicitly address the allocation of responsibility in the firm’s financial reporting process and focus on its effects on earnings quality.2 Second, we study a two-stage reporting game where the CEO has superior

information about the (financial or non-financial) incentives of the CFO compared to the financial market.

Second, our analysis is related to the literature on the interaction of CFO and CEO in financial reporting decisions. Indjejikian and Matĕjka (2009) analyze the simultaneous incentive contract choice for the CEO and the CFO of a firm. Both parties provide productive effort, but the CFO can additionally overstate earnings and improve reporting quality by reducing the measurement error. Friedman (2014) and Friedman (2016) analyze the interaction of the CEO’s and CFO’s decisions in an optimal contracting setting. The CEO provides productive effort while the CFO can improve reporting quality and at the same time can bias the financial report. Friedman (2014) assumes that a powerful CEO can force the CFO to choose a bias level in his best interest. High CEO power implies lower reporting quality and higher bias levels if the CFO is primarily accountable for corporate misreporting. The assignment of responsibility should reduce the powerful CEO’s willingness to apply pressure to account for these detrimental effects. Friedman (2016) does not consider the case that the CEO is accountable for reporting bias, but discusses the incremental effect of effort interactions between CEO and CFO. Improved reporting quality reduces the CEO’s (productive) effort costs. In this sense, improving reporting quality serves multiple purposes (monitoring, decision-making, and contracting).

Within this strand of literature, our analysis is most closely related to Friedman (2014). We also discuss the role of CEOs in influencing the firms’ earnings management and study the implications of CFO and CEO responsibility. In contrast to Friedman (2014), we do not consider an optimal contract choice, but assume exogenous incentives tied to the firm’s stock price and focus on the effect of the CFO and CEO responsibility on the financial market. Our analysis accounts for the sequential structure of the reporting interaction and different sources of asymmetric information between CFO and CEO as well as between the firm and the financial market.

reporting bias by his subordinates on earnings quality. If CFO’s can hardly be held accountable for misreporting earnings, increasing the responsibility of the CEO becomes more beneficial, i.e., the CFO’s and CEO’s responsibility for the CFO’s bias in financial reports are substitutes with regard to earnings quality. Finally, we address the role of compensation disclosure and transparency with regard to managerial incentives. We show that higher responsibility of the CEO is beneficial if there is high uncertainty about the CFO’s incentives in the market. Such uncertainty potentially arises from limited transparency with regard to his financial incentives and career opportunities.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the model and the assumptions underlying the analysis. Section 3 considers the optimal biasing strategies of the CFO and the CEO and Section 4 characterizes the rational expectations equilibrium. Section 5 presents comparative static results for earnings quality, and Section 6 concludes.

2. The Model

We consider a one-period reporting game with three strategic players: a risk-neutral Chief Financial Officer (CFO) and a risk-neutral Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of a firm and a competitive, risk-neutral financial market. The firm’s fundamentals, v, are normally

distributed, (0,σ2)

v

v N .

The timeline of the reporting game consists of three dates. First, the CFO of the firm engages in earnings management and provides a potentially biased interim report to the CEO. Second, after observing the CFO’s report, the CEO may engage in earnings management and issues a report to the financial market. Finally, the financial market uses the CEO’s report to adjust the market price of the firm.

Earnings Management

The CFO privately observes the firm’s earnings, e, that are correlated with the firm’s

fundamentals, e = +v ε, where ε N(0,σε2) is independently distributed noise. After

observing the firm’s earnings, the CFO prepares an interim earnings report and submits the

report to the CEO. The interim report, rF , equals the sum of the firm’s earnings and a bias

F

b that the CFO introduces into his report, rF = +e bF.

the CFO’s cost of managing earnings is 2 ( )2

known marginal cost of biasing and the normally distributed random variable ε (0,σ2)

F N F

captures idiosyncratic circumstances that influence the CFO’s misreporting costs, such as legal

(mis-)reporting leeway (Dye & Sridhar 2004). While the CFO knows the realization of εF

before choosing his bias level, it is unobservable by both the CEO and the market. Finally, the parameter γ∈[0,1] measures the responsibility of the CFO for the chosen reporting bias.3 We

explicitly allow for constellations in which the CFO is not fully accountable for the consequences of his earnings management decision, γ <1. There are several reasons why this might be the case. For instance, managers are protected by limited liability and are only partially accountable for the distortion caused by misreporting. Furthermore, accounting systems in general offer some leeway in interpreting standards. Lower values of γ might

represent accounting systems in which CFOs have sufficient discretion in choosing accounting rules. Then, accounting bias can be achieved within the legal scope defined by the standard setters and there is only a small probability for fines or reputational losses.4 Moreover, γ

might reflect problems with enforcement. Depending on the governance system, CFOs possibly get away cheaply. The probability of detection and the consequential fines are lower than intended by regulation. In this sense, γ can be interpreted as an effective responsibility.

We capture increasing CFO’s responsibility by increasing γ . For example, the

Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, Section 302, requires the CFO to certify the financial statements of the firm together with the CEO, thus increasing the personal accountability of the CFO.

The CEO privately observes the CFO’s earnings report, engages in earnings management and

issues a final report to the financial market. The final report equals rE = +rF bE, where bE is

the bias that the CEO introduces into the earnings report. We assume that the CEO’s cost of

managing earnings is ( )2

2 ⋅ ⋅κ + +ε E

F E E

c

b b . Similarly to the CFO’s marginal cost of biasing,

0 > E

c is publicly known and the normally distributed random variable ε E N(0,σE2) reflects

3 The parameter restriction γ∈[0,1] does not influence our results. Assuming that the CFO cannot be held fully accountable for his chosen reporting bias, we provide an intuitive reason for increasing the responsibility of the CEO for the CFO’s misreporting. However, as we will show in Section 5, increasing the responsibility of the CEO does not necessarily improve earnings quality.

idiosyncratic circumstances that influence the CEO’s misreporting costs. The CEO privately

knows the realization of εE. The variable κ∈[0,1] formalizes the idea that the CEO may be

(partly) held accountable for the reporting bias introduced by the CFO.5 As mentioned above,

the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, Section 302, requires both the CFO and the CEO to certify financial statements. It thus posits a joint responsibility of the CFO and the CEO for the appropriate presentation of the firm’s operations and financial conditions. This rule may increase the CEO’s liability for the CFO’s reporting bias for several reasons. On the one hand, the enforcement agency may fail to disentangle the responsibility for the reporting bias and partly attribute the decision to manage earnings to the CEO. On the other hand, the enforcement agency may deliberately postulate a shared responsibility of the CFO and CEO for misreporting, since the CEO is the primarily responsible person for the activities of a firm. He decides on the adequacy of internal controls and should be held accountable for financial misreporting by his subordinates, e.g., the CFO.

CFO’s and CEO’s Utility

We assume that both the CFO’s and the CEO’s utilities depend on the market price of the firm. The interest in market price may arise, e.g., due to explicit compensation arrangements, intention to sell equity holdings or repurchase shares of the firm, influencing the labor market’s perception of the managerial talent (e.g., Feller and Schäfer 2017) or simply the desire to increase the scope of control. The CFO’s and CEO’s utilities are linear in the market price

( )E

the CFO know the actual incentive rate of the CFO, the market does not observe xF. Instead,

the market holds beliefs about the CFO’s interest in stock price and hence about his incentive to engage in earnings management. In particular, the market knows the a priori distribution of

5 Note that we do not impose any restrictions on the relation between κ and γ . For κ γ= =1, both parties are jointly responsible for the misreporting of the CFO. A centralization of responsibility is depicted by κ =1 and

0

F

x which is normal with mean µx >0 and variance σx2. Note that the actual realization of

F

x might be negative. In fact, managers may have an interest in decreasing the stock price of

the firm if, e.g., they plan a management buyout, are about to repurchase shares or receive stock options. In addition, if the CFO has the ambition to become the CEO of the firm, he might be interested in managing earning downward under the current CEO.6 In our model, the

variance σ2

x of the incentive rate reflects the market’s uncertainty about the CFO’s incentives. In contrast, we assume that the CEO’s incentives, xE, are observable by all parties. This

assumption reflects that there is more public information about the CEO’s incentives than about the CFO’s motivation. Disclosure rules usually have a stronger focus on the CEO compared to his subordinates. Furthermore, it is likely that CFOs are driven by career concerns to a greater extent than CEOs who already hold the top position within the firm. These implicit incentives impede the ability of the market to infer the incentives of the CFO as opposed to the CEO.

Based on the CEO’s report, ,rE the market adjusts the price of the firm to the expected firm

value given all available information, ( )P rE =E v r[ | ] E . The uncertainty about the CFO’s and

CEO’s incentives to bias earnings reports prevents the market from perfectly inferring the bias in the CEO’s report in equilibrium.7

Figure 1 summarizes the timeline of the reporting game.

FIGURE 1

Timeline of the reporting game

6 If CEOs increasingly bear responsibility for firms’ financial reports, they must have accounting knowledge. This potentially improves CFOs’ claim to be a candidate for the CEO succession.

To obtain a tractable solution to our reporting game, we restrict the analysis to linear equilibria. The equilibrium consists of the CFO’s and the CEO’s earnings reports and the market price reaction to the CEO’s report. We assume the following linear strategies:

0 ε

3. CFO’s and CEO’s Reporting Strategies

The CFO’s Problem and Optimal Reporting Bias

The CFO chooses the bias bF to maximize his expected utility in (1) given the earnings e, the

realization of the incentive weight xF and the cost of biasing the report εF and given the

conjectures about the CEO’s final report ˆrE and the resulting market price ˆ ˆP r( )E :8

strategies as given in equations (4) and (5). Then, the first-order condition yields the CFO’s choice of bias in his earnings report:9

*

Given the linear structure of the CFO’s bias in equation (3), we can conclude:

0 0

The CFO’s choice of bias in the interim report is independent of actual earnings (Fischer &

Verrecchia 2000, Ewert & Wagenhofer 2005) and decreases in the realization of εF (Dye &

Sridhar 2004). In line with Fischer and Verrecchia (2000), a higher market response to the

earnings report β and a lower CFO’s cost of biasing the report cF result in a higher amount

8 The caret “^” denotes a conjecture. 9

of CFO’s earnings management. Intuitively, the CFO’s degree of responsibility for biasing the interim report decreases the bias. Since the interim report is evaluated by the CEO prior to being issued to the market, the coefficient on the CFO’s incentive weight also depends on the CEO’s reaction to the interim report. In particular, the bias increases as the CEO’s conjectured

reaction vr to the CFO’s report increases.

The CEO’s Problem and Optimal Reporting Bias

The CEO chooses the bias bE to maximize his expected utility in (2) given the realization of

the CFO’s incentive weight xF, the interim earnings report rF, the cost of biasing the report

E

The CEO’s cost of biasing the report to the market depends on the realization of the cost of

biasing the report εE. However, if the CEO is partially responsible for reporting bias

potentially introduced by the CFO, i.e., κ >0 , the CEO’s expected cost of bias also depends on the CFO’s biasing decision. While the CEO does not directly observe the bias chosen by

the CFO, he makes a conjecture based on the observation of the CFO’s incentives xF and the

CFO’s interim report rF. The CEO’s optimal choice of bias in the final report follows from

the first-order condition:

where the conditional expectation of the CFO’s cost of biasing earnings is given by:

2 2

Comparing this result to the linear equilibrium strategy in (4) shows that

0

The CEO’s reaction to the interim report, vr, plays a crucial role in the reporting game. The

overstatement bias in the CFO’s interim report. However, the CEO corrects the CFO’s report only if he is partially accountable for the CFO’s misreporting, i.e., κ >0. The CEO’s bias can be positive or negative depending on the CEO’s discount of the interim report.

Proposition 1 summarizes the results concerning the CEO’s response to the CFO’s report.

Proposition 1. Holding the financial market reaction β constant,the CEO’s discount of the CFO’s interim report increases if

i. the responsibility of the CEO for the CFO’s misreporting κ increases;

ii. the uncertainty about the CFO’s cost of biasing σF2 increases.

The CEO’s responsibility for the CFO’s earnings management determines his reaction to the interim report. The higher the CEO’s responsibility for the CFO’s reporting bias, the more the CEO optimally reduces his bias in response to the CFO’s report. While the CEO is aware of the CFO’s incentives to bias earnings, there is some remaining uncertainty about his cost of biasing the report. As long as the CEO is accountable for the CFO’s reporting bias, he chooses a lower level of bias if the uncertainty about the CFO’s cost of managing earnings increases. Interestingly, the CEO’s reaction to the CFO’s report is independent of the CFO’s

responsibility for his own misreporting, i.e., 0 γ

4. Market Pricing Function and Equilibrium

The market price of the firm equals the expected value of the firm given the CEO’s earnings report. Thereby, the market rationally conjectures the CFO’s and the CEO’s optimal linear reporting strategies in (3) and (4). Proposition 2 summarizes the equilibrium in the hierarchical reporting game.

Lemma 1. Thereexists alinear equilibrium in which i. the CFO chooses the reporting bias

*

ii. the CEO chooses the reporting bias

iii. and the market pricing depends linearly on the CEO’s report with the positive weight β

that is implicitly defined by the following equation:

2

In the following, we analyze the quality of reported earnings. We highlight how earnings quality is linked to the uncertainty about the CFO’s and CEO’s cost of biasing, the uncertainty about the CFO’s incentives and our primary variables of interest, the responsibilities of the CFO and the CEO for the CFO’s reporting bias.

We measure the quality of reported earnings as (1) value relevance of earnings and (2) price efficiency. Value relevance of earnings is typically measured as the slope coefficient in the regression of market price on earnings (e.g., Fischer & Verrecchia 2000; Ewert & Wagenhofer 2005). In our model, value relevance corresponds to the weight β on the CEO’s earnings

report in the market pricing function. Price efficiency captures the extent to which public and private information is reflected in the market price. Therefore, price efficiency is related to the relative reduction of uncertainty about fundamental value due to the information included in

the market price [ | ]2 σ

v

Var v P

(Fischer & Verrecchia 2000). The measure reflects the remaining

uncertainty in the market price after the issuance of the earnings report. To analyze comparative statics for price efficiency, it is useful to define the following measure of price efficiency (Heinle & Verrecchia 2016):

2 2 2

Some parameters in our model affect earnings quality in a predictable way consistent with the prior literature. For example, in line with Fischer and Verrecchia (2000), increasing the CFO’s

marginal cost of biasing cF deters earnings management and as a consequence increases value

relevance of earnings β and price efficiency V. As in Dye and Sridhar (2004), the CEO’s

marginal cost of biasing cE does not affect the quality of the reported earnings. In the

comparative statics for the value relevance of earnings and the price efficiency with regard to the key model parameters.

Lemma 2. Comparative statics

i. Variation in the value relevance of earnings β:

2 0

ii. Variation in the price efficiency V :

2 0

In our model, there are two sources of uncertainty that prevent the market from perfectly inferring the reporting bias. First, the market observes the CEO’s incentive weight on the firm’s market price, but is uncertain about the incentives of the CFO (Fischer & Verrecchia 2000). Second, the CFO’s and the CEO’s cost of biasing is uncertain (Dye & Sridhar 2004).

With regard to the uncertainty about the CFO’s incentives σ2

x, we find that a higher uncertainty decreases the earnings quality as measured by the value relevance of earnings β

and price efficiency V . This result complements the finding of Fischer and Verrecchia (2000)

in a non-hierarchical model that the uncertainty about managerial incentives negatively affects earnings quality. Thus, our result emphasizes the importance of transparency not only about the CEO’s incentives, but also about the incentives of other top managers such as the CFO, and provides support for increased compensation disclosure requirements concerning the top management team.

The second source of uncertainty in our model that prevents the market from perfectly inferring the reporting bias is the uncertainty about the CFO’s and the CEO’s cost of biasing,

2

σF and 2

σE respectively. As in Dye and Sridhar (2004), the uncertainty about the CEO’s cost

of biasing the earnings report σ2

E intuitively weakens the relation between reported earnings and market price. It thus decreases value relevance of earnings and price efficiency. The effect

of the uncertainty about the CFO’s cost of biasing earnings σ2

Uncertainty about the CFO’s Cost of Biasing

The uncertainty about the CFO’s cost of biasing σ2

F has an ambiguous effect on earnings quality. Price efficiency is unambiguously decreasing in the uncertainty about the CFO’s cost of biasing. However, the relation between the reported earnings and market price may be strengthened or weakened with increasing uncertainty about the CFO’s cost of biasing. Proposition 2 summarizes this result.

Proposition 2.Earnings quality and the uncertainty about the CFO’s biasing costs

(a) Value relevance of earnings β may be increasing or decreasing in the uncertainty about

the CFO’s cost of biasing σF2. Value relevance of earnings is more likely increasing in

the uncertainty about the CFO’s cost of biasingif

i. the CFO’s marginal cost of biasing, c , is sufficiently low; F

ii. the CFO’s responsibility for his reporting bias, γ , is sufficiently low;

iii. the uncertainty about the CFO’s incentives, σx2 , is sufficiently high;

iv. the uncertainty about the CEO’s cost of biasing, σE2, is sufficiently low.

(b) Price efficiency V is decreasing in the uncertainty about the CFO’s cost of biasing.

The ambiguous effect of the uncertainty about the CFO’s cost of biasing earnings results from the hierarchical structure of our model. After observing the potentially biased interim report, the CEO may himself engage in earnings management before he forwards the final report to the market. The uncertainty about the CFO’s cost of biasing thus has two opposing effects on the relation between the reported earnings and market price. On the one hand, all else equal, increasing uncertainty about the CFO’s cost of biasing decreases the value of reported earnings in conveying information about true earnings. As a consequence, the value relevance of reported earnings β decreases. On the other hand, the uncertainty about the CFO’s cost of

biasing affects the CEO’s response to the earnings reported by the CFO and thus the CEO’s optimal choice of bias. According to Proposition 1 (i), the CEO’s discount of the interim report is higher with increasing uncertainty about the CFO’s cost of biasing. This indirect effect increases the value relevance of the reported earnings.

incentives to bias the interim report. For sufficiently high CFO’s cost of biasing, sufficiently high uncertainty about the CFO’s incentives and sufficiently low responsibility of the CFO for his own misreporting, the indirect effect dominates and the value relevance of earnings is increasing in the uncertainty about the CFO’s cost of biasing. In this case, the CFO has particularly strong incentives to bias earnings which enhances the importance of the supervision by the CEO. Anticipating higher incentives of the CFO to bias earnings, the CEO discounts the CFO’s interim report to a greater extent, strengthening the relation between the reported earnings and market price.

The last result in part (a) of the Proposition 2 relates to the CEO’s incentives to bias earnings.

If the uncertainty about the CEO’s cost of managing earnings, σ2

E, is sufficiently low, the CEO has weak incentives to bias earnings. In this case, increasing uncertainty about the CFO’s cost of biasing enhances the CEO’s incentives to correct the CFO’s interim report, thus strengthening the value relevance of earnings.

With regard to price efficiency, the result in part (b) of the Proposition 2 shows that the direct effect always dominates and the price efficiency is unambiguously decreasing in the uncertainty about the CFO’s cost of biasing.

CFO’s Responsibility for His Own Misreporting

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, Section 302, “Corporate Responsibility for Financial Reports”, requires the CFO and the CEO of the firm to certify financial statements. Thereby, Section 302 enhances the personal responsibility of the top executives. We first analyze the effect of the CFO’s responsibility for his own misreporting γ on the quality of reported

earnings. Proposition 3 provides the comparative static result.

Proposition 3. Value relevance of earnings β and price efficiency V are increasing in the CFO’s responsibility for his own misreporting γ .

Proposition 3 confirms the intuition that higher responsibility of the CFO for his own misreporting makes earnings more value-relevant and enhances price efficiency.10 Our result

highlights that in order to improve earnings quality, regulators should acknowledge the crucial

10

Similarly, Ewert and Wagenhofer (2005) find that increasing the tightness of accounting standards implies

role the CFO plays in ensuring the appropriateness of financial reports and increase the CFO’s accountability. Thus, Section 302 seems an important step towards achieving this goal.

CEO’s Responsibility for the CFO’s Misreporting

Section 302 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 emphasizes the joint responsibility of the firm’s CFO and CEO for an appropriate presentation of the firm’s operations and financial condition. As the CFO is primarily responsible for the preparation of the financial statements, the requirement to certify the accurateness of the financial statements enhances personal responsibility of the CEO for his own misreporting as well for potential misreporting by the CFO. Proposition 4 presents the comparative static result for the effect of the CEO’s responsibility for the CFO’s misreporting κ on the quality of reported earnings.

Proposition 4. Value relevance of earnings β and price efficiency V may be increasing or decreasing in the CEO’s responsibility for the CFO’s reporting bias κ. Value relevance of

earnings and price efficiency are more likely increasing in the CEO’s responsibility for the

CFO’s reporting biasif

i. the CFO’s marginal cost of biasing, c , is sufficiently low; F

ii. the CFO’s responsibility for his reporting bias, γ, is sufficiently low;

iii. the uncertainty about the CFO’s incentives, σx2 , is sufficiently high;

iv. the uncertainty about the CEO’s cost of biasing, σE2, is sufficiently low.

At first glance, the result in Proposition 4 seems counterintuitive. If the regulator aims at increasing the earnings quality, it seems logical to increase the accountability of both executives who may manage earnings. Following this line of reasoning, we would expect that enhancing the accountability of the CEO for potential misreporting by the CFO should help to unambiguously improve the quality of reported earnings. However, Proposition 4 highlights a trade-off in making the CEO responsible for the CFO’s biasing. On the one hand, increasing the CEO’s responsibility for the CFO’s misreporting enhances the CEO’s incentives to correct the CFO’s bias in the reported earnings. To illustrate this effect, consider the CEO’s optimal choice of bias for κ =0:

β ε

⋅

= E −

E E

E

x b

If κ =0, the CEO chooses the bias independently of the CFO and has no incentives to scrutinize the CFO’s interim report. The benefit of the CEO’s supervision is particularly high if the CFO has strong incentives to manage earnings, i.e., if the CFO can bias earnings at low cost, if the CFO’s responsibility for his own misreporting is low and if the uncertainty about the CFO’s incentives is high.

On the other hand, increasing the CEO’s responsibility for the CFO’s misreporting also increases the noise in the reported earnings, since the CEO’s costs of adjusting his bias are uncertain as well. This introduces additional noise into the final report. As a consequence, a higher uncertainty about the CEO’s cost of biasing earnings results in a lower benefit of the CEO’s supervision.

Proposition 4 shows that, contrary to the expectation, the responsibility of the CFO γ and the

responsibility of the CEO κ for the CFO’s misreporting are substitutes instead of complements. All in all, the results in Proposition 4 show that increasing the responsibility of both the CFO and the CEO does not necessarily imply higher earnings quality.

Numerical Example on the Effects of the CEO’s Responsibility

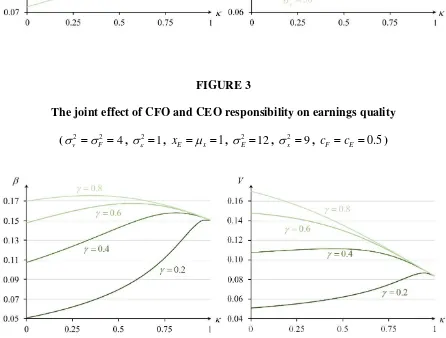

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the consequences of increasing CEO responsibility κ. Figure 2 shows the effect of higher CEO responsibility on value relevance (graph on the left-hand side) and on price efficiency (graph on the right-hand side) depending on the variance of the CFO’s

incentives. If the incentives of the CFO are perfectly known in the financial market (σ2 =0 x ), earnings quality and price efficiency are unambiguously decreasing in higher CEO responsibility. In such cases, increasing responsibility is counter-productive. As the uncertainty about the CFO’s incentives increases, value relevance and price efficiency are increasing for low levels of CEO responsibility. There are critical values of CEO responsibility, which maximize value relevance and price efficiency respectively.11 Generally,

higher uncertainty about the CFO’s incentives reduces earnings quality.

Figure 3 shows the interaction of CFO and CEO responsibility. If the CFO is largely responsible for his own misreporting, regulatory attempts to increase CEO responsibility cannot significantly improve the results. Instead, higher levels of CEO responsibility reduce value relevance as well as price efficiency in the financial market. A beneficial effect of higher

11 Note that value relevance and price efficiency are not maximized by the same value of κ. This is obvious from the case 2 4

x

CEO responsibility occurs if the CFO is hardly responsible for his own misreporting decision. This highlights the substitutive relationship between CEO and CFO responsibility regarding the informational value of the financial report.

FIGURE 2

Uncertainty about CFO incentives and the effect of increasing CEO responsibility

(σ2 =σ2 =4 v F ,

2 1 ε

σ = , xE =µx=1, σE2 =12, cF =cE =0.5, γ =0.4)

FIGURE 3

6.

Conclusion

In this study, we address financial reporting as a two-stage process between the CFO and the CEO of a firm and discuss the implications of making the CEO accountable for the CFO’s reporting bias on earnings quality. In contrast to prior literature we explicitly account for asymmetric information not only between the financial market and the firm management, but also within the firm between the CFO and the CEO.

Consistent with intuition, we find that increasing the CEO’s responsibility for CFO’s misreporting enhances his incentives to challenge the financial reports and to partially reverse the bias, thereby increasing earnings quality. However, we show that making the CEO accountable for the CFO’s reporting bias also has an adverse effect on earnings quality. As the CEO’s cost of biasing the report is unknown, increasing his responsibility introduces additional noise to the reported earnings. As a consequence, the earnings quality may decrease or increase in the CEO’s responsibility for the CFO’s reporting bias. In contrast, we find that the CFO’s responsibility for the chosen reporting bias has an unambiguous positive effect on earnings quality. Further, our results indicate a substitutive relation between the CFO’s and the CEO’s responsibility for reporting bias: Assigning higher responsibility to the CEO is more likely to improve earnings quality if the CFO is hardly accountable for his own biasing decision. Increasing the CEO’s responsibility can be particularly beneficial if he has superior information about the CFO’s incentives.

In our setting, we capture an important aspect of current regulation, namely that the requirement to certify financial reports imposes accountability on CEOs not only for their own bias, but also for potential misreporting at lower hierarchical levels. Thus, our results have implications for regulators who should consider the potentially adverse effects of enhancing the CEO’s responsibility for misreporting of his subordinates. According to our results, increasing the CEOs’ responsibility might improve earnings quality if CFOs can hardly be called to account for their misreporting. Higher responsibility of the CEO can also be beneficial if there is high uncertainty about the CFO’s incentives in the market. This might be the case because of weak disclosure requirements and limited transparency with regard to compensation arrangements.

Appendix

The CFO’s Optimal Reporting Bias. The CFO conjectures the CEO’s final report ˆrE and the

price of the firm ˆ ˆP r( )E are linear strategies as given in equations (4) and (5):

The CFO’s optimal choice of bias * F

b in (7) follows from the first-order condition:

2

The CEO’s Optimal Reporting Bias. The CEO conjectures that the market price linearly

depends on his report according to (5):

ˆ ˆ( )= + ⋅α βˆ

E E

P r r . (20)

The CEO’s expected cost of biasing the report follows as:

[ ]

[

[

]

]

(

)

Using equations (20), (21) and (23) and the fact that the conjectures are self-fulfilling in equilibrium gives the first-order condition in (10).

Proof of Proposition 1. The proof follows directly from the first-order conditions for the

CEO’s optimal choice of bias * E

conditional expectation of the firm’s fundamental value follows as:

(

)

Matching this result with equation (5), the market’s reaction to the CEO’s reportβ is given

where the conjectures are correct in equilibrium. Matching the parameter specifications of the CFO’s and the CEO’s strategies in equations (8) and (12) and the market pricing function in equation (27) yields the linear equilibrium in Lemma 1.

Proof of Lemma 2. Part (i) of Lemma 2 follows from implicit differentiation of the market

pricing function β : Part (ii) of Lemma 2 follows from implicit differentiation of the price efficiency V :

∂ and simplifying yields:

2

Proof of Proposition 2. Part (a). The financial market’s reaction to the CEO’s report is

increasing in 2

2 2 2

Substituting this result yields:

2

Comparative statics in part (i)-(iv) of Proposition 2, (a), follow from implicit differentiation of 2

Part (b) follows from the proof of Lemma 2.

Proof of Proposition 3. The result in Proposition 3 follows from the proof of Lemma 2. Proof of Proposition 4. First, consider value relevance β. The financial market’s reaction to

2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

Substituting (42) into (50) yields:

2 2 2 2

Comparative statics with regard to value relevance β in part (i)-(iv) of Proposition 4 follow

from implicit differentiation of Φκ:

2 2 2

Substituting (42) into (58), define:

2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

Comparative statics with regard to price efficiency V in part (i)-(iv) of Proposition 4 follow

References

BURNS,NATASHA AND SIMI KEDIA. 2006. The Impact of Performance-based Compensation

on Misreporting, Journal of Financial Economics, 79(1): 35–67.

CASKEY,JUDSON,VENKY NAGAR, AND PAOLO PETACCHI. 2010. Reporting Bias with an Audit

Committee, The Accounting Review, 85(2): 447–481.

CHANG, HSIHUI, JENGFANG CHEN, WOODY M. LIAO, AND BIRENDRA K. MISHRA. 2006.

CEOs’/CFOs’ Swearing by the Numbers: Does It Impact Share Price of the Firm?, The

Accounting Review, 81(1): 1–27.

DICHEV, ILIA D., JOHN R. GRAHAM, CAMPBELL R. HARVEY, AND SHIVA RAJGOPAL. 2013.

Earnings Quality: Evidence from the Field, Journal of Accounting and Economics,

56(2-3): 1–33.

DIKOLLI, SHANE S., WILLIAM J. MAYEW, AND MANI SETHURAMAN. 2016. The CEO-CFO

Relationship and CEO Compensation, Working Paper.

DYE, RONALD A. AND SRI S. SRIDHAR. 2004. Reliability-Relevance Trade-Offs and the

Efficiency of Aggregation, Journal of Accounting Research, 42(1): 51–88.

EWERT,RALF AND ALFRED WAGENHOFER. 2005. Economic Effects of Tightening Accounting

Standards to Restrict Earnings Management, The Accounting Review, 80(4): 1101–

1124.

FELLER,MIRÓ AND ULRICH SCHÄFER. 2017. The Effect of Financial Incentives and Career

Concerns on Reporting Bias, Working Paper.

FENG,MEI,WEILI GE,SHUQING LUO, AND TERRY SHEVLIN. 2011. Why Do CFOs Become

Involved in Material Accounting Manipulations? Journal of Accounting and Economics

51 (1/2): 21–36.

FISCHER, PAUL E. AND ROBERT E. VERRECCHIA. 2000. Reporting Bias, The Accounting Review, 75(2): 229–245.

FRIEDMAN,HENRY L. 2014. Implications of Power: When the CEO Can Pressure the CFO to

Bias Reports. Journal of Accounting and Economics 58(1): 117–141.

FRIEDMAN,HENRY L. 2016. Implications of a Multi-Purpose Reporting System on CEO and

CFO Incentives and Risk Preferences, Journal of Management Accounting Research

GEIGER,MARSHALL A. AND DAVID S.NORTH. 2006. Does Hiring a New CFO Change Things?

An Investigation of Changes in Discretionary Accruals, The Accounting Review 81 (4):

781–809.

GEIGER, MARSHALL A. AND PORCHER L. TAYLOR. 2003. CEO and CFO Certifications of

Financial Information, Accounting Horizons, 17(4): 357–368.

HEINLE,MIRKO S. AND ROBERT E.VERRECCHIA. 2016. Bias and the Commitment to Disclose,

Management Science, 62(10): 2859–2879.

INDJEJIKIAN,RAFFI AND MICHAL MATĚJKA. 2009. CFO Fiduciary Responsibilities and Annual

Bonus Incentives. Journal of Accounting Research 47(4): 1061–1093.

JIANG,JOHN,KATHY R.PETRONI, AND ISABEL Y.WANG. 2010. CFOs and CEOs: Who have

the most influence on earnings management? Journal of Financial Economics 96(3):

513–526.

LUSKIN,DON. 2002. Law Requiring CEO Certification of Financial Statements is the Work of

Idiots, Capitalism Investor, available at

http://capitalisminvestor.com/2002/08/16/law-requiring-ceo-certification-of-financial-statements-is-the-work-of-idiots/

SANKAR,MANDIRA R. AND K. R.SUBRAMANYAM. 2001. Reporting Discretion and Private

Information Communication through Earnings, Journal of Accounting Research, 39(2):

365–386.

STEIN,JEREMY C. 1989. Efficient Capital Markets, Inefficient Firms: A Model of Myopic

Corporate Behavior, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104(4): 655–669.

WOOD,ROBERT W. 2013. CEO Held Liable For CFO's Embezzlement, Forbes, available at: