PerOla Öberg is professor of political science in the Department of Government, Uppsala University, Sweden. He has published articles, books, and book chapters on interest groups, corporatism, industrial relations, public administration, trust, and deliberation. His current research focuses on deliberative participation in public policy making and the use of learning, experience, and “knowledge” in political processes.

E-mail: perola.oberg@statsvet.uu.se

Katrin Uba is researcher in the Department of Government, Uppsala University, Sweden. Her main research interests are social movements and protest events, particularly the political outcomes of citizens’ contentious actions. Her current research focuses on the outcomes of pro-tests against the school closures in Swedish municipalities during the last two decades and the consequences of protests against the economic crisis in Europe.

E-mail: katrin.uba@statsvet.uu.se

Public Administration Review, Vol. 74, Iss. 3, pp. 413–422. © 2014 by The American Society for Public Administration. DOI: 10.1111/puar.12199.

PerOla Öberg Katrin Uba Uppsala University, Sweden

Increased citizen participation is proposed to remedy democratic defi cits. However, it is unclear whether such participation improves reason-based discussions or whether it serves mainly as a safety valve for discontented citizens. To what extent does citizen-initiated participa-tion involve reason-based arguments? Th is study examines citizens’ reason giving based on unique data on citizens’ contacts with local authorities in Sweden. It provides support for proponents of deliberative participation, as an unexpected amount of contacts provided reasons for clearly stated positions and invitations to a construc-tive dialogue with authorities. Th ere is variation across issues. More confl ictual issues involve fewer intentions to participate in a reasoned exchange of arguments. Th e study shows that citizens deliver more reason-based input to democratic decision making

when they prepare their position in groups than when they partici-pate as individuals. Findings are preliminary but clearly illustrate the fruitfulness of widening the research agenda on civic engage-ment in politics and public administration.

C

itizen engagement in public politics andadministration is a subject of long-standing debate in political science and public administration. Recent proposals to increase citizens’ opportunities for deliberative input into public decision making and administration have been criticized because they may spur interest advocacy and promote special interests over public interests (Hendriks 2011, 8; Nabatchi et al. 2012; Rosenberg 2007, 336). Some authors argue that the idea of participatory-deliberative public administration “rests on weak and naïve foundations” (Baccaro and Papadakis 2009; Rosenberg 2007). Citizens do not want to participate in a reasoned exchange of arguments, that is, deliberation; they simply aim to advocate their interests and want their voice to be listened to (Hibbing and Th eiss-Morse 2002; Sanders 1997). Th erefore, deliberative

participation should not be seen as a solution to problems of legitimacy in the political process. On the other hand, proponents of citizen engagement and collaborative governance are optimistic that citizens will engage in deliberative problem solving (Ansell and Gash 2008; Emerson, Nabatchi, and Balogh 2012; Fung 2006; Lukensmeyer and Brigham 2005; Nabatchi 2012; Neblo et al. 2010; Öberg 2002).

Th e scholarly disagreement also concerns the question of how individuals’ input into the deliberative proc-esses diff ers from the input of groups. Some scholars argue that individuals behave more deliberatively than groups. Groups tend to defend particular outcomes and are the “deliberative trouble” (Hendriks 2011, 5;

Sunstein 2000). Th is view is contested by those claiming that “group reasoning often surpasses individual reasoning” (Mercier and Landemore 2012, 249–50) because organized citizens learn how to deliberate and gather information in support of an argument (Van der Meer and Van Ingen 2008). Th is article contributes to these discus-sions by exploring the quality of arguments that citizens put forward when initiating contacts with public administration and participat-ing in public processes. Th e focus is only on a limited part of civic engagement, namely, citizen-initiated participation in the form of written complaints and questions sent to local public authorities. Th is kind of civic engagement has been almost neglected in prior research (Aars and Strømsnes 2007; Th omas and Streib 2003, 84). Besides research on which groups of citizens engage in these activities and how often (e.g., Petersson 1999; Th omas and Melkers 2001), very little is known about the content of the arguments and the quality of discussion in these incoming streams of messages (Th omas and Streib 2003; Norris and Reddick 2012). Hence, the article aims to contribute to research on civic engagement (e.g., Nabatchi et al. 2012) and to

Civil Society Making Political Claims: Outcries,

Interest Advocacy, and Deliberative Claims

Th is article contributes to these

discussions by exploring the

quality of arguments that citizens

put forward when initiating

contacts with public

during 2011; (2) all written complaints about school closure processes in one municipality during the period 2007–09. In this article, we show that citizens provide clear statements and reasons to an unexpected extent, given the one-shot character of the activity and the issue studied. We also show that groups are more likely to engage in a reasoned exchange of arguments by providing reasons for their positions and signaling a willingness to discuss them.

Deliberative Civic Engagement and Political Claim Making

Th e concern with modern public administration from a demo-cratic point of view has renewed interest in citizen involvement. Scholars argue that in the United States, there is “an erosion of civil society and civic engagement and, more specifi cally, an erosion of civic skills and dispositions among the general public” (Nabatchi 2010, 378). Th e cure is seen in intelligent and eff ective citizen par-ticipation (Nabatchi 2010, 381, citing Wildavsky 1979). Although this solution might imply several diff erent things, it is often con-nected to ideas of deliberative democracy (Fung 2006; Lukensmeyer and Brigham 2005; Nabatchi 2010, 384; Rosenberg 2007). For example, discussion of “collaborative governance” presumes that citizen participation will take the form of problem solving and that stakeholders are involved in reason-based deliberation (Ansell and Gash 2008). Consequently, one of the interactive processes in col-laborative governance is deliberation or “candid and reasoned com-munication” (Emerson, Nabatchi, and Balogh 2012, 12). However, as stated in the introduction, there are disagreements over the pos-sibilities of deliberative civic engagement in public policy.

Some of the criticism has been taken seriously by researchers interested in empirical research on deliberation. Th ey propose to relax the requirement of perfect deliberation in every situation and instead acknowledge that several components can contribute diff er-ent functions to a deliberative system (Dryzek and Niemeyer 2010; Parkinson and Mansbridge 2012). Th is means that the deliberative-ness of civic engagement in the real world (as opposed to abstract ideal situations) can be interpreted in a meaningful way. We argue that even written questions and complaints from the public—which are often one-shot inputs—may contribute to a deliberative system under certain circumstances. New and better information provided by citizens as input to a policy process may contribute to delibera-tive knowledge enhancement (Barabas 2004; Papadopoulos 2012, 127). Furthermore, reason giving might spur deliberation among other citizens (Rosenberg 2007) and reinforce a norm of delibera-tion in a larger context (cf. Gambetta 1998). On the other hand, if skeptics such as Hibbing and Th eiss-Morse (2002) are right and civic engagement mainly consists of outcries without the intention

to contribute to a reasoned discussion, it is diffi cult to see how this kind of engagement could contribute to a deliberative system.

While we are interested in the deliberative quality of civic engagement and use that phrase throughout this article, the charac-ter of the activity studied here implies that we focus on only parts of deliberation. We ask whether positions are clearly stated, whether reasons for the position are provided, and whether there are intentions to engage in a discussion with the authorities. Defi nitions of deliberation usually include several literature that connects theoretical and empirical research on

delibera-tion (Th ompson 2008; Bächtiger and Hangartner 2010).

We acknowledge that written complaints are far from a traditional deliberative process, but we are encouraged by recent studies emphasizing that every situation cannot be perfectly deliberative. Instead, diff erent institutions may contribute with diff erent func-tions to produce system-level deliberation (Dryzek and Niemeyer 2010; Parkinson and Mansbridge 2012, 2). We consider the main component of deliberation to be a social interaction based on

reasoned discussion (Bächtiger et al. 2010; Dryzek and Niemeyer

2010; Parkinson and Mansbridge 2012) and therefore examine the degree of reason giving. Th is means that we exclude other important parts of deliberation, such as listening to others with respect with a preparedness to change preferences, and focus only on the quality of arguments provided by citizens who interact with public offi cials. If citizen-initiated contacts involve a lot of reason giving, this might provide new information and fi ll a knowledge-enhancing function (i.e., an epistemic function) in a deliberative system (Parkinson and Mansbridge 2012, 11). In this way, citizen engagement can contrib-ute to democratic legitimacy and improve the quality of decisions in public administration.

Prior empirical studies of citizens’ reason giving have mainly focused on participation in small groups (Black 2012; De Vries et al. 2010) or online participation (Loveland and Popescu 2011; Schlosberg, Zavestoski, and Shulman 2008). While the qualities of reasoned discussion in face-to-face situations are well documented, only modest equivalent evidence is found for online practices. Empirical evaluations of citizens’ deliberation beyond mini-publics or online forums are rare, and little is said about individual–group diff erences. Th erefore, this article addresses these two issues. First, we exam-ine whether critics of deliberation are correct: do citizens use little reason giving and mostly express their discontent through simple “outcry,” or do they actually make clear statements with reasons and even signal a willingness for serious interaction with public offi cials? Second, we explore whether the degree of reason giving varies sig-nifi cantly across participating individuals and groups.

Our evaluation of reason provision is based on an analysis of writ-ten contributions from members of the public regarding public school issues in Sweden. Although school issues might not be fully representative for all citizen-initiated contacts with local authorities, this is an important area for civic engagement in many countries. In Sweden, school policy is an important part of the welfare state, and schooling is organized at the municipal level (Edlund and Johansson Sevä 2013). Because municipalities have a high degree of local self-government (Sellers and Lidström 2007),

contacting municipal authorities about school issues represents a classical engagement in pub-lic decision making. In fact, discontent with the issues of education and schooling is one of the most important drivers of citizens’ politi-cal activism in Sweden (Kriesi and Westholm 2010; Solevid 2009).

We use a unique data set on citizens’ contacts with local authorities in Sweden and analyze two types of data: (1) all written complaints regarding elementary and preschool issues sent to 12 municipalities

Th e character of the

activ-ity studied here implies that

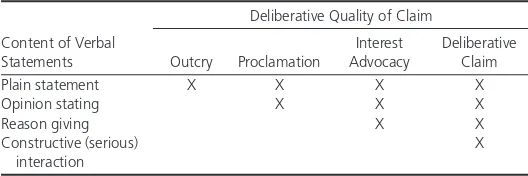

they are, in fact, engaged in a “reasoned exchange of arguments” with policy makers. Th is, in turn, may force the policy makers to reply in the same matter. Consequently, such a claim has better opportunities to contribute to a deliberative system. Hence, the deliberative quali-ties of claims in this article refer only to the content of the claim, as we do not study deliberation before submitting the comments or the whole interaction with representatives of the authorities. Considering that eventual claims are located somewhere between the described ideal types, we examine whether the claim is clearly stated and elaborated (opinion stating), whether there are reasons given for the opinion (reason giving), and whether the contact has any intention to open up an interaction (constructive, serious interaction). Th e relationship between the content of verbal statements and the delib-erative quality of the claim is shown in table 1.

We regard a claim that contains all the content in the fi rst column of table 1—a plain statement, clear opinion stating, reason giving, and an invitation to constructive (serious) interaction—to be a

deliberative claim. A claim with a clearly stated opinion and reason

giving but without obvious reference that the author has any inten-tion to discuss the matter in a constructive interacinten-tion is labeled

an interest advocacy. A stated opinion without any reason given is

only a proclamation of a position; it is a declaration of an opinion without really arguing why it is important and without trying to persuade others to endorse it. Finally, if the verbal statement only informs the audience about some facts, a situation, or a process, it is aplain statement. A claim that just consists of a plain statement is, from a deliberative quality point of view, only an outcry; it is just a remark or a protest against the current state regarding something of importance to the complaining person(s).1 Th e diff erences among

these categories are described in more detail in the Method and Data section of this paper, but here, it suffi ces to say that we expect to see variation of the deliberative quality of claims across individu-als and groups.

Th ere is little empirical knowledge on whether participating citizens actually contribute some reasoned opinion (Baccaro and Papadakis 2009). Prior studies on citizens’ online participation in policy processes have found that the structure of such forums in general facilitates nondeliberative arguments, for example, self-expressive monologue rather than reasoned arguments that welcome negotia-tion of diff erent arguments (e.g., Wilhelm 2000). Written com-plaints are probably closer to online participation than mini-publics or other small-scale forums. Hence, our fi rst hypothesis suggests that citizens’ written complaints mainly fall into the category of

outcry.

Even though a direct contact with authorities is often assumed to be an individually based form of participation (Aars and Strømsnes components: that the actors justify their positions, listen to each

other, show mutual respect, and are willing to reevaluate their initial preferences (e.g., Steenbergen et al. 2003, 31). Th e examination of all these components would require diff erent, dialogue-based mate-rial. Data on citizen-initiated contacts allow us to study only how actors justify their position, that is, reason giving (sometimes reason providing). Th is is an important part of deliberation because an opinion has to be expressed, and it has to be possible for others to evaluate the reason for that opinion (Habermas 1984; Mercier and Landemore 2012, 245). Still, to study citizens’ contacts or political claim making (Giugni 2011, 300) can be seen as problematic from a deliberative perspective. However, we diverge from components of ideal communicative action (Bächtiger et al. 2010, 34, 40) and agree with others that self- interest (Mansbridge et al. 2010), interest advocacy (Hendriks 2011), and even certain kinds of rhetoric can be accepted in deliberation, given certain conditions (Dryzek 2010).

One can imagine two ideal types of claims for deciding whether they are part of deliberative reasoning. First, a claim can be an angry or perhaps aggressive remark or complaint. It has no argument for the position given, and the author(s) has no serious intention to be involved in an interaction with others:“You [expletive] idiots should do something to make children’s roads to school safer” is an example of such an outcry. It is very diffi cult to know what this person wants or why and how the problem should be solved. Should bus stops be safer? Should slippery winter walkways be treated with sand or salt? Speed limits decreased outside schools? Moreover, it is unlikely that the speaker seriously expects the claim to be taken into account by anyone. It is just an expression of disapproval or anger. In fact, many petitions actually state claims that are nothing more than outcries (e.g., a petition against school closure claims, “Save our school!”).

Second, a deliberative claim would involve more precise opin-ion stating, with reason giving based on a small investigation and references to expert knowledge. It might also include alternative suggestions and an explicit invitation to discuss the matter to fi nd solutions to the problem. Consider this ideal type of deliberative claim:

I have noticed that accidents outside schools in our munici-pality have increased. School Y is one particular example. I have attached a document of injuries outside School Y over the last three years. According to the police, this problem is due to the high maximum speed limit. Moreover, I have attached an investigation of the situation, which shows that every second car exceeds the speed limit. According to research, a reduction of the speed limit by XX would decrease accidents by XX. Th erefore, we demand that the speed limit outside schools is reduced by XX. An alternative action would be to make road crossings safer by installing traffi c lights or building a tunnel or a bridge. Th is has been done in munici-pality Q and has proven very effi cient, but also expensive. I expect you to contact me very soon to discuss a solution to this problem.

We argue that the deliberative quality of participation with claims in line with the second ideal type is greater than that of claims like the fi rst, less elaborated one. A more elaborated claim that provides reasons indicates that citizens believe that arguing matters and that

Table 1 Citizen Engagement in Public Policy and Deliberative Quality

Content of Verbal Statements

Deliberative Quality of Claim

Outcry Proclamation

Interest Advocacy

Deliberative Claim

Plain statement X X X X

Opinion stating X X X

Reason giving X X

Constructive ( serious) interaction

on paper or digitally, they are considered public documents unless they contain personal information. Th e municipalities had removed all personal information from the documents we examined.

Our empirical data encompassed two types of complaints. Th e fi rst type comprised 451 written complaints sent to the committee of elementary and preschool policies in 12 of 290 Swedish municipali-ties—Ale, Degerfors, Falköping, Flen, Håbo, Höganäs, Knivsta, Kramfors, Landskrona, Uppsala, Varberg, and Ånge—during 2011. Th e sample was stratifi ed to represent diff erent-sized municipalities, as the size of the population was considered likely to aff ect the kinds of problems that citizens complain about.3 Th e sample includes

small municipalities such as Degerfors (9,641 inhabitants), medium ones such as Kramfors (18,911 inhabitants), and the largest ones such as Uppsala (197,787 inhabitants). Th e data provide a good pic-ture of the contacts between citizens and municipality bureaucrats regarding elementary and preschool issues and are a good basis for exploring the deliberative character of citizens’ claims in Sweden.

Th e second set of data comprised 47 written complaints regarding proposals to close three primary schools in Uppsala municipality during the period 2007–09. Th e issue of school closures is decided by the same committee as elementary and preschool policies, but the issue has higher salience than other, more typical issues that the committee deals with (including the quality of school build-ings, education, and personnel). Uppsala municipality was selected because it had many proposals for closing primary schools during a short period of time. Th is allowed us to focus on the deliberative quality of the complaints and, at the same time, keep constant the factors related to time and municipality, which could aff ect the vari-ation of deliberative quality of citizens’ complaints.

Our focus on school issues has some advantages and caveats. Th e major advantage is that it engages a majority of Swedish citizens. Education is seen as an important part of the welfare state, and these questions mobilize more political activism than health care or envi-ronmental issues (Kriesi and Westholm 2010; Solevid 2009). One possible weakness of the data set is the fact that school issues tend to be more emotional and personal than, for example, environmental issues. Hence, we might fi nd fewer well-reasoned claims than in other policy areas. On the other hand, such a focus on a least likely case would also strengthen our argument about the prevalence of deliberative claims in Swedish public administration.

It may be questioned whether this kind of civic engagement, which often has a one-shot character, can be analyzed as taking place in a public arena with elements of deliberation. However, it is a com-munication over public issues directed to targeted receivers of the message. Th e municipal administrations are obliged to read and respond. Hence, it is a two-way communication, or “a transfer of information wherein individuals act both as senders and receiv-ers” (Nabatchi 2012, 702). On the fi ve-point continuum of the International Association for Public Participation’s Spectrum of Public Participation, such communication should be positioned somewhere between “consult” and “involve,” and thus at the point in the spectrum when public input begins to be considered. Because the documents are publicly available, it is a semipublic arena in which the correspondence may be read by outsiders, for example, by other citizens, politicians, and journalists.

2007, 95), many citizens discuss their opinions with friends, neigh-bors, colleagues, or a civil society organization they belong to. Every society contains innumerable such deliberative groups (Sunstein 2000, 72) where citizens meet and “test” their arguments. Th is begs a classic question in political science, namely, how public delibera-tion is aff ected by the fact that some individuals deliberate in groups (or factions; see, e.g., Rousseau 1762) before entering the public arena.

A “standard view of deliberation” is that group discussions lead to better outcomes (Sunstein 2000, 73, referring to Aristotle and Rawls, for example). Th is might be so because groups prepare their claims, formulate their positions, and strengthen their arguments in internal discussion before deliberating in a larger, open arena (Van der Meer and Van Ingen 2008). Group collaboration also allows mustering common resources to fi nd evidence for (and against) the position taken and may help drop extreme arguments that do not help the cause. Th e growing self-confi dence that comes with pooled resources, in combination with a laundering of preferences (Goodin 1986), could induce a tone and way of approaching poli-ticians and bureaucrats that promotes deliberative behavior. If this is the case, written communication signed by groups should tend to provide reason to well-argued positions, while individuals should tend to use this channel more as a safety valve for their outcries and grievances.

However, prior research also indicates that groups do not necessar-ily contribute positively to deliberation. Groups are often less likely to be impartial and less ready to shift their selected preferences (Hendriks 2011, 5). Because of their self-insulation and engage-ment in enclave deliberation, groups may create “serious deliberative trouble” by boosting initial anger and going to “extremes” (Sunstein 2000, 119). Instead of contributing to constructive interaction with reasons, this might lead to unreasonable outcries and threats of protest actions or obstruction of public policy—that is, a lower deliberative quality of claims delivered by groups.

Hence, there are diverging arguments in the literature regarding the deliberative quality of claims across individuals and groups (Mercier and Landemore 2012, 243). Considering the long-term Swedish tradition of collective mobilization (Öberg and Svensson 2012), it is reasonable to expect that arguments stated in written complaints sent by groups would fall into the category of deliberative claim

more often than those sent by individuals.

Before we proceed to examine which of the expectations has empiri-cal support in the case of Swedish citizens’ contacts with their loempiri-cal municipalities, we describe our data and measures.

Method and Data

Th e citizen-initiated participation in public administration that we study here refers to the possibility of submitting complaints to local governments.2 In Sweden, all citizens can send “suggestions

sources other than personal experience to support their argument, do not present an alternative solution, and are not clearly open for discussion, they are categorized as proclamations. A typical example is a letter that provides a precise description of the problems with some preschool facilities (for example, the lack of places in general and the quality of food or education) and demonstrates the author’s negative attitude toward the situation. Th e letters that clearly express opposition to a proposed school closure and give some simple rea-sons for this statement fall into this category.

If the argument in the letter is supported by any source of informa-tion, regardless of whether it is biased or correct (Bächtiger et al. 2010; cf. Renwick and Lamb 2012), it is considered an indica-tor of reason giving. References to personal experience only (the most common source; cf. Stromer-Galley 2007, 5), however, are not considered a suffi cient reason to qualify as deliberative com-munication in this study. We agree, for example, with Chambers (2009) and Dryzek (2010) that rhetoric and even storytelling can be acceptable elements in deliberation, but only in certain forms. References to personal experience in our material are usually only an explanation for why the citizen has approached local authorities and are seldom components of a more universal argument or examples used to persuade the audience. To include this kind of personal experience would dilute the meaning of “reason-based.” Hence, if the author has made some personal investigation or used a scientifi c or media source to support an argument, it is considered a reasoned claim. We agree with Stromer-Galley (2007, 4) that sourcing and reasoned opinion are closely related and do not require a category of their own. Such letters mostly express the (reasoned) interests of the authors and do not present any alternative solutions, nor are they open to further discussion of the argument. Hence, they fall into the category of interest advocacy. An example is the following letter to Håbo municipality:

Th e ratio of children to adults in the municipalities’ kinder-gartens has increased from 5.0 to 5.7 from 2006 to 2010. Research has shown that large groups are threatening chil-dren’s development, learning, and health. Th e current political majority has recognized the problem and distributed money for solving it. When do we see the results?

Finally, if the document has some indicators of constructive

interac-tion, it is considered a deliberative claim. Such indicators, however,

are diffi cult to fi nd. We suggest that constructive interaction has the following characteristics: the author of the letter provides some alternative solutions, demonstrates openness to diff erent opinions, and does not use an aggressive or upset tone in the argument. We have tried to distinguish pure passion, which is acceptable in Th e letters we examined were on paper or were sent to the

munici-pality by e-mail4 and were categorized as “suggestions and

com-plaints” to the committee of elementary and preschool issues in the stated 12 municipalities during 2011. Many of the letters (127) were continuations of some earlier “conversation” and thus were excluded from further analysis. We also discovered that some of the letters (44) sent to the municipalities were not actually “complaints” but rather direct questions about educational services or unclear statements that could not be coded.5 We excluded all these cases

from our analysis and carefully read, coded, and categorized 370 letters (including the 46 letters on school closures).6

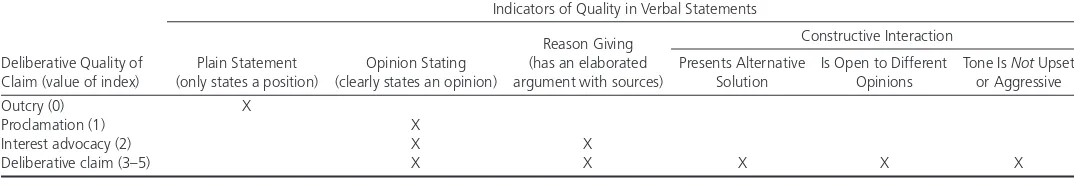

Th ere are no standard measurements of deliberation to be used (Gastil, Knobloch, and Kelly 2012; Th ompson 2008, 505). Th e most developed and widely used measurement, the Discourse Quality Index (DQI) (Bächtiger and Hangartner 2010; Steiner et al. 2004), is not applicable to our case, for two reasons. First, it was developed for studies of parliamentary debates and is too detailed, requiring information that is not available in our citizens’ com-plaints. Second, the DQI is anchored in Habermasian discourse ethics, which we diverge from and which makes several of the DQI measures inapplicable here. We categorized the letters on the basis of the deliberative quality of the claims presented in the letters: outcry, proclamation, interest advocacy, and deliberative claim (as in table 1). Hence, we tried to capture whether the claim maker had taken a less or more developed position and whether reasons were given for that position. Table 2 demonstrates how the categories of deliberative quality are related to the indicators of the quality of verbal statements. To simplify the analysis, we composed a cumula-tive index of deliberacumula-tive quality ranging from 0 to 5.

A (usually) shorter letter that only states some position but does not present a clear opinion or an elaborated argument is an indicator of a plain statement and therefore categorized as an outcry. Here are three typical examples:

Save Jumkil school! (a petition with 1,151 names)

All the families of the children who started preschool in the autumn were invited to the school today, but we were not! We learned about that on Facebook! It is very bad! (an e-mail signed by “annoyed parents”)

Keep the library open during the city festival next year! (an anonymous e-mail)

Claims that clearly state a position and also motivate their opinion are indicators of opinion stating. As these claims do not use any

Table 2 Coding of the Deliberative Quality of Claims

Deliberative Quality of Claim (value of index)

Indicators of Quality in Verbal Statements

Plain Statement (only states a position)

Opinion Stating (clearly states an opinion)

Reason Giving (has an elaborated argument with sources)

Constructive Interaction

Presents Alternative Solution

Is Open to Different Opinions

Tone Is Not Upset or Aggressive

Outcry (0) X

Proclamation (1) X

Interest advocacy (2) X X

Deliberative claim (3–5) X X X X X

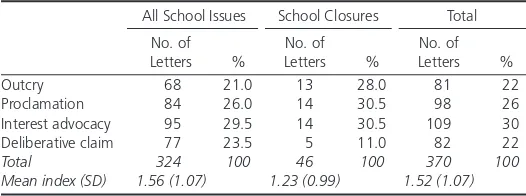

or 5. Th is suggests that openness and friendly tone are probably too high requirements for deliberative claims used in the citizen-initiated participation. In summary, the answer to the fi rst question is no, because the outcries form only one-fi fth of citizen-initiated contacts. Th e same proportion of claims state opinions that are sup-ported by elaborated arguments that make use of sources other than personal experience and propose an alternative solution. Table 4 describes the kinds of sources of information that citizens used.

Half of the sources referred to were based on something more than just personal experience (personal experience is often related to a sin-gle event, such as the behavior of a teacher). Th is means that citizens in many cases do contribute “knowledge” that might not have been noticed otherwise. Th is is particularly noticeable in the case of the letters against school closures (e.g., Jumkil school), which provided detailed analysis of a municipal proposal and demonstrated its fl aws. In summary, citizen-initiated contacts seem to be a channel by which

citizens deliver opinions, sometimes sup-ported by evidence and in a tone that invites interaction. Th is means that citizen-initiated participation in local politics is a factor that can contribute to a deliberative system. To some extent, this depends on how the authori-ties react, a question that is beyond the aim of this study.7

Prior studies suggest that some issues call for more deliberative claims and discussions than other issues. To examine this, we coded our letters on the basis of the issue at stake, in other words, depend-ing on the claims made by the author as well as compardepend-ing the let-ters about less contested school issues to the ones about the school closures. We have already noted that the mean index varies across the degree of confl ict, as the index for the letters on school clo-sures is lower than for the letters on other school issues. Th is is also noticeable in table 5, which presents the distribution of the index across fi ve fi rst-stated aims of the letter.8

Our second expectation suggested that letters from groups would score higher on our deliberative quality index than the letters from individuals and thereby would contribute more to a delibera-tive system. We categorized the senders based on how the letters were signed. When two parents from the same family signed, we grouped them together under “one individual or family.” Loose and temporary groups, such as a group of parents who apparently have come together for the issue at hand, were coded “ad hoc group.” Social movements and interest groups were separated based on their organizational structure. Interest groups (e.g., trade unions) have a deliberation (Chambers 2009), from coercion and threat, which

are not. As this category includes three diff erent indicators, the index could theoretically range from 3 to 5. Few cases, however, fall into this category. One example is an e-mail in which the author expresses disappointment with the fact that there is a defi cit of 40 preschool places in his part of the city and authorities have just closed one preschool. He has looked for several sources for the explanation and suggests some solutions for the situation—all in a friendly tone, that is, not upset or aggressive.

We also coded other characteristics of these letters: the actor(s) who sent the letter, the main aim and issue of the letter, the frame of the argument, and whether the letter was answered. Coding was mostly done by a research assistant, but the authors made reliability checks, and in the case of disagreements, the majority opinion was used. Th e coding details for these categories are described in the appendix.

Findings: Outcries or Deliberative Claims?

Th e fi rst question to be answered is whether citizen-initiated contacts with local authori-ties are mostly outcries, as the prior research on online participation suggests. Table 3 describes our fi ndings, which show that citizens sometimes use deliberative claims

when they contact local authorities (22 percent of all examined letters). Still, outcries (22 percent) and proclamations (26 percent) form almost half of all statements (48 percent). As expected, there are more outcries (28 percent) and fewer deliberative claims (11 per-cent) in the more confl ictual school closures. Th is is also described by the signifi cantly lower mean index (1.23) for school closures than for all examined claims (1.52).

Th e majority of the 82 deliberative claims fulfi ll only one of the three requirements (alternative solution, open to diff erent opinion, or tone not upset) and therefore have an index of 3 rather than 4

Table 3 Citizens Contacting Municipalities: Outcries or Deliberative Claims?

All School Issues School Closures Total

No. of

Letters %

No. of

Letters %

No. of

Letters %

Outcry 68 21.0 13 28.0 81 22

Proclamation 84 26.0 14 30.5 98 26

Interest advocacy 95 29.5 14 30.5 109 30

Deliberative claim 77 23.5 5 11.0 82 22

Total 324 100 46 100 370 100

Mean index (SD) 1.56 (1.07) 1.23 (0.99) 1.52 (1.07)

T able 4 Sources Used When Reasons Given for an Opinion

Sources Number % of Total

Personal experience 234 47.6

Own simple investigation 109 22.2

Own advanced investigation (calculations, legal references)

21 4.3

Reference to media 5 1.0

Use of offi cial reports and documents 12 2.4

Use of scientifi c resources 26 5.3

Other (undefi ned sources) 85 17.3

Note: The total number 492 is far larger than 370 because the letters could use multiple sources. For example, 72 letters used no sources, 99 used only personal experience, and 59 used the writers’ own simple investigation and personal experience.

Tab le 5 Deliberative Quality by Issue

Issue Mean Index No. of Cases

Everyday activities 1.83 234

Decision procedure 2.09 23

Legal mistake 2.10 48

Made decision 1.76 (2.08)** 43

Made proposal 1.67 (1.84)** 31

Other issues 1.92 38

Note: For the categories “Made decision” and “Made proposal,” the mean index is signifi cantly higher if the letters on school closures (the mean in parentheses) are excluded. Some of the letters are categorized by multiple issues, so the number of cases adds to more than 370.

Citizen-initiated participation

in local politics is a factor that

can contribute to a deliberative

Conclusion

Citizen-initiated contact with local authorities is often more than just outcries or proclamations, and the deliberative quality of stated claims clearly varies across individuals and groups. More than half of the coded contacts provided reasons for clearly stated positions and even invited a constructive dialogue with authorities. Considering that we examined a very “personal” type of citizens’ participation— written complaints to municipalities often express discontent with something important to the complaining person—this is a surpris-ingly high fi gure. In the case of the more political issue of school closures, the outcries are more common than the fully deliberative claims. Hence, our general fi ndings provide clear empirical support for proponents of deliberative participation (cf. Fung 2006), who argue that citizens are able and willing to provide reasoned argu-ments even in confl icts that aff ect them personally. However, it is important to note that the deliberative quality of the claims varies across the issues at stake.

We found more outcries and fewer deliberative claims when citizens protested against the closure of their schools. Interest advocacy is also common; although these lack alternative proposals, some of the most elaborated argumentation is given in such complaints. As stated earlier in relation to Hendriks (2011), this is not necessar-ily bad news to proponents of deliberation. Reason giving is a key aspect of deliberation, and even if these actors do not explicitly state the intention to participate in constructive dialogue, it forces civil servants and politicians to argue. Moreover, several diff erent sources are used, even some “own simple investigation” or more advanced investigations, which means that civil society presents alternative information to local authorities. Some complaints are supported by detailed analyses with (correct) objections to the municipality’s offi cial economic calculation and include elaborated alternative suggestions. At least to a certain extent, citizen-initiated contact can contribute to an epistemic function in a deliberative system.

Our results, which demonstrate that the quality of arguments is higher when citizens participate in groups and when the issue is framed as a collective good, support scholars arguing for group

reasoning. Hence, civil society delivers more reason-based input to democratic decision making when citizens prepare their position in groups than when they participate as individu-als. It may well be that groups are only better to formulate reasons and are still less open-minded, so we should draw cautious conclu-sions. However, only a few letters from groups are outcries or proclamations, and the diff er-ence between individuals and groups is larger in regard to deliberative claims than interest advocacy. Hence, groups not only provide resources for reason giving but also aff ect the tone in a deliberative direction.

Although our study is good news for those who believe that citizen-initiated participation can contribute positively to a deliberative system, several caveats have to be taken into account. Th e data used in the article are indeed limited in several aspects, and, to some extent, this should be considered an exploratory study in which we illustrate an approach that could be applied in more complex issues and in other contexts before more defi nite conclusions can traditional organization with formal memberships and statutes that

state internal decision-making bodies. Social movements are loose networks of sustained collective action (e.g., neighborhood socie-ties). Table 6 describes the distribution of the index across these actors.

As expected, a large majority of the letters are sent by individuals or families; the deliberative quality of these letters (1.49) is signifi cantly lower than the index of any of the groups.9 Th is supports the

argu-ment that groups provide an arena for deliberation before eventual participation and have more resources for performing their own investigations or making use of numerous sources—all of which increases the deliberative quality of their arguments. Hence, there are no indications that “groups go to extremes.”

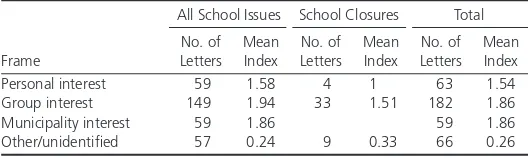

Th e quality of claims also varies across framing. We coded letters that frame the issues as only important to the author as “personal interest” and letters that frame their argument as something impor-tant to the community or some group as

“group interest.” Letters that frame the claims as something that is an improvement for the municipal situation are coded as “municipal-ity interest.” Cases we could not defi ne fell into the category of “other.” Table 7 describes the distribution of the index across these categories; it is clear that letters with mainly personal frames have lower deliberative qual-ity, that is, fewer reasons are given and fewer sources provided to support personal interests.

Once again, we can see that a more collective approach is conducive to more deliberative claims, and the low deliberative index of the letters on school closures “pulls down” the total index for groups. Th e quality of deliberation index is higher for claims that are not framed as a personal interest. Th is is not self-evident. Th ere are reasons to expect that claims that are framed as personal interests need to be even better argued and delivered in a deliberative tone in order to be accepted. Th is does not seem to be the case in the claims in this study.

Tabl e 7 Deliberative Quality by Frame

Frame

All School Issues School Closures Total

No. of

Personal interest 59 1.58 4 1 63 1.54

Group interest 149 1.94 33 1.51 182 1.86

Municipality interest 59 1.86 59 1.86

Other/unidentifi ed 57 0.24 9 0.33 66 0.26

Civil society delivers more

rea-son-based input to democratic

decision making when citizens

prepare their position in groups

than when they participate as

individuals.

Table 6 Deliberative Quality by Actors

All school Issues School Closures Total No. of

One individual or family 277 1.53 30 1.10 307 1.49

Ad hoc group 14 2.57 6 1.26 20 2.10

Social movements 1 3.00 6 1.83 7 2.00

Interest group 3 2.67 3 2.33 6 2.50

Other 18 0.92 1 0 19 0.89

4. Municipalities usually have guidelines for archiving e-mails and letters, while the content of the phone calls is not similarly archived and was inaccessible for our analysis.

5. We also know how municipalities respond to these letters, but such an analysis is beyond the aim of this article.

6. Coding was mostly done by the research assistant, but to improve the coding reliability, both of the authors were also involved in the fi rst stage of the coding process. Th e codebook is available upon request.

7. We know that 69 percent of the letters were answered by the municipality and that there is no signifi cant correlation between the probability of responding and our index of the deliberative quality of the letters.

8. “Everyday activities” in table 5 refers to service-related questions usually handled by bureaucrats and often related to various benefi ts and entitlements that citizens think they should receive.

9. Th e diff erence of the means for individuals and groups is signifi cant at the 95 percent level for the total sample and for the cases of “Municipalities 2011” but not for the letters against school closures.

References

Aars, Jacob, and Kristin Strømsnes. 2007. Contacting as a Channel of Political Involvement: Collectively Motivated Individually Enacted. West European Politics

30(1): 93–120.

Ansell, Chris, and Alison Gash. 2008. Collaborative Governance in Th eory and Practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Th eory 18(4): 543–71. Baccaro, Lucio, and Konstantinos Papadakis. 2009. Th e Downside of Participatory-

Deliberative Public Administration. Socio-Economic Review 7(2): 245–76. Bächtiger, André, and Dominik Hangartner. 2010. When Deliberative Th eory Meets

Empirical Political Science: Th eoretical and Methodological Challenges in Political Deliberation. Political Studies 58(4): 609–29.

Bächtiger, André, Simon Niemeyer, Michael Neblo, Marco R. Steenbergen, and Jürg Steiner. 2010. Disentangling Diversity in Deliberative Democracy: Competing Th eories, Th eir Blind Spots and Complementarities. Journal of Political Philosophy 18(1): 32–63.

Barabas, Jason. 2004. How Deliberation Aff ects Policy Opinions. American Political Science Review 98(4): 687–701.

Bergh, Andreas, and Gissur Ó. Erlingsson. 2009. Liberalization without

Retrenchment: Understanding the Consensus on Swedish Welfare State Reforms.

Scandinavian Political Studies 32(1): 71–93.

Black, Laura W. 2012. How People Communicate during Deliberative Events. In

Democracy in Motion: Evaluating the Practice and Impact of Deliberative Civic Engagement, edited by Tina Nabatchi, John Gastil, G. Michael Weiksner, and Matt Leighninger, 59–81. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Chambers, Simone. 2009. Rhetoric and the Public Sphere: Has Deliberative Democracy Abandoned Mass Democracy? Political Th eory 37(3): 323–50. De Vries, Raymond, Aimee Stanczyk, Ian F. Wall, Rebecca Uhlmann, Laura

J. Damschroder, and Scott Y. Kim. 2010. Assessing the Quality of Democratic Deliberation: A Case Study of Public Deliberation on the Ethics of Surrogate Consent for Research. Social Science and Medicine 70(12): 1896–1903.

Dryzek, John S. 2010. Rhetoric in Democracy: A Systematic Appreciation. Political Th eory 38(3): 319–39.

Dryzek, John S., and Simon Niemeyer. 2010. Foundations and Frontiers in Deliberative Governance. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Edlund, Jonas, and Ingemar Johansson Sevä. 2013. Is Sweden Being Torn Apart? Privatization and Old and New Patterns of Welfare State Support. Social Policy and Administration 47(5): 542–64.

Emerson, Kirk, Tina Nabatchi, and Stephen Balogh. 2012. An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Th eory 22(1): 1–29.

be drawn. First, we do not know how representative our material is for citizen-initiated contact in Sweden or elsewhere. Th e written complaints regarding the issues of elementary school or education could be diff erent from those on the environment or infrastructure. As noted previously, the issues that involve some confl ict, such as the question of school closures, might encourage less deliberative participation. Th erefore, it would be important to pay attention to a larger variety of issues in further research. Second, comparative research in other contexts would be most welcome. In their study, Neblo et al. (2010, 577) found that respondents seemed more willing to deliberate with a government in which they had more trust. Hence, we might expect less deliberative behavior in countries where government and interpersonal trust are lower than in Sweden. Moreover, Sweden is known to be particularly rational, techno-cratic, and pragmatic compared to most other countries (Bergh and Erlingsson 2009). If this is true, it might very well be the case that we are dealing with self-reinforcing processes: citizens behave more deliberatively—state opinions clearly supported by reason—if they know that it pays off in the context in which they participate (cf. Gambetta 1998). In such contexts, individuals’ capacity to deliber-ate may evolve (cf. Rosenberg 2007). In other contexts, in which citizens believe that offi cials care less for reason, a negative reinforc-ing mechanism that contradicts deliberation might operate. If this is the case, it has important implications for democratic theory and empirical research. Establishing institutions for deliberative par-ticipation may have diff erent eff ects on democracy and democratic legitimacy in diff erent contexts (Bächtiger and Hangartner 2010, 625). What contextual factors could explain such negative or posi-tive self-reinforcing processes? (if they exist). Th is is one of several aspects of deliberative civic engagement that calls for more research.

We have shown that many citizens think that reason and evidence matter when they try to infl uence public administration. Such an engagement might also encourage policy makers to respond with rea-soned arguments, which, in turn, will have implications for how we train and recruit personnel to public administration. Th e challenge is to create conditions for public administration to be infl uenced by a reasoned exchange of arguments, without opening itself up to lobby-ing and manipulation that may exacerbate political inequality.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Chris Ansell, Jörgen Hermansson, Mar-cus Holdo, Malin Holm, Julia Jennstål, Oscar Söderlund, Torsten Svensson, and the editors and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. Th e study is part of the research program “Civil Society and Enlightened Welfare Politics,” which is funded by the Swedish Research Council.

Notes

1. It is apparent that the complainer is dissatisfi ed—it is an expression of dissatis-faction—but it is not clear exactly what the complaint is about, or even whether the issues are within the municipality’s decision-making competence. No clear opinion is stated.

2. Th is diff ers from another form of contacting called “citizens’ advice,” which many municipalities have initiated since 2002. We look only at actions taken by citizens’ initiative.

Fung, Archon. 2006. Varieties of Participation in Complex Governance. Special issue, Public Administrative Review 66: 66–75.

Gambetta, Diego 1998. Claro! An Essay on Discursive Machismo. In Deliberative Demo-cracy, edited by Jon Elster, 19–43. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Gastil, John, Katie Knobloch, and Meghan Kelly. 2012. Evaluating Deliberative

Public Events and Projects. In Democracy in Motion: Evaluating the Practice and Impact of Deliberative Civic Engagement, edited by Tina Nabatchi, John Gastil, G. Michael Weiksner, and Matt Leighninger, 205–20. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Giugni, Marco. 2011. Welfare States, Political Opportunities, and the Mobilization of the Unemployed: A Cross-National Analysis. Mobilization: An International Journal 13(3): 297–310.

Goodin, Robert E. 1986. Laundering Preferences. In Foundation of Social Choice Th eory, edited by Jon Elster and Aanund Hylland, 75–101. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Habermas, Jürgen. 1984. Th e Th eory of Communicative Action: Reasons and Rationalization of Society. Trans. Th omas McCarthy.Boston: Beacon Press. Hendriks, Carolyn M. 2011. Th e Politics of Public Deliberation: Citizen Engagement

and Interest Advocacy. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hibbing, John R., and Elizabeth Th eiss-Morse. 2002. Stealth Democracy: Americans’ Beliefs about How Government Should Work. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Kriesi, Hanspeter, and Anders Westholm. 2010. Small-Scale Democracy: Th e Determinants of Action. In Citizenship and Involvement in European Democracies: A Comparative Analysis, edited by Jan W. van Deth, José R. Montero, and Anders Westholm, 255–79. New York: Routledge.

Loveland, Matthew T., and Delia Popescu. 2011. Democracy on the Web: Assessing the Deliberative Qualities of Internet Forums. Information, Communication and Society 14(5): 684–703.

Lukensmeyer, Carol J., and Steven Brigham. 2005. Taking Democracy to Scale: Large-Scale Interventions—for Citizens. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science

41(1): 47–60.

Mansbridge, Jane, James Bohman, Simone Chambers, David Estlund, Andreas Føllesdal, Archon Fung, Cristina Lafont, and Bernard Manin. 2010. Th e Place of Self-Interest and the Role of Power in Deliberative Democracy. Journal of Political Philosophy 18(1): 64–100.

Mercier, Hugo, and Helene Landemore. 2012. Reasoning Is for Arguing: Understanding the Successes and Failures of Deliberation. Political Psychology

33(2): 243–58.

Nabatchi, Tina. 2010. Addressing the Citizenship and Democratic Defi cit: Th e Potential of Deliberative Democracy for Public Administration. American Review of Public Administration 40(4): 376–99.

———. 2012. Putting the “Public” Back in Public Values Research: Designing Participation to Identify and Respond to Values. Public Administration Review

72(5): 699–708.

Nabatchi, Tina, John Gastil, G. Michael Weiksner, and Matt Leighninger, eds. 2012.

Democracy in Motion: Evaluating the Practice and Impact of Deliberative Civic Engagement. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Neblo, Michael A., Kevin M. Esterling, Ryan P. Kennedy, David M. J. Lazer, and Anand E. Sokhey. 2010. Who Wants to Deliberate—and Why? American Political Science Review 104(3): 566–83.

Norris, Donald F., and Christopher G. Reddick. 2012. Local E-Government in the United States: Transformation or Incremental Change? Public Administration Review 73(1): 165–75.

Öberg, PerOla. 2002. Does Administrative Corporatism Promote Trust and Deliberation? Governance 15(4): 455–75.

Öberg, PerOla, and Torsten Svensson. 2012. Civil Society and Deliberative Democracy: Have Voluntary Organisations Faded from National Public Policy?

Scandinavian Political Studies 35(3): 246–71.

Papadopolus, Yannis. 2012. On the Embeddedness of Deliberative Systems: Why Elitist Innovations Matter More. In Deliberative Systems: Deliberative Democracy at the Large Scale, edited by John Parkinson and Jane Mansbridge, 125–50.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Parkinson, John, and Jane Mansbridge. 2012. Deliberative Systems: Deliberative Democracy at the Large Scale. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Petersson, Olof. 1999. Demokrati på svenskt vis. Demokratirådets rapport 1999.

Stockholm, Sweden: SNS Förlag.

Renwick, Alan, and Michael Lamb. 2012. Th e Quality of Referendum Debate: Th e UK’s Electoral System Referendum in the Print Media. Electoral Studies 32(2): 294–304.

Rosenberg, Shawn W. 2007. Rethinking Democratic Deliberation: Th e Limits and Potential of Citizen Participation. Polity 39(3): 335–60.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 1762. Th e Social Contract. Trans. G. D. H. Cole. Buff alo, NY: Prometheus, 1988.

Sanders, Lynn M. 1997. Against Deliberation. Political Th eory 25(3): 347–76. Schlosberg, David, Stephen Zavestoski, and Stuart W. Shulman. 2008.

Democracy and E-Rulemaking: Web-Based Technologies, Participation, and the Potential for Deliberation. Journal of Information Technology and Politics 4(1): 37–55.

Sellers, Jeff erey M., and Anders Lidström. 2007. Decentralization, Local Government, and the Welfare State. Governance 20(4): 609–32.

Solevid, Maria. 2009. Voices from the Welfare State: Dissatisfaction and Political Action in Sweden. PhD diss., Department of Political Science, Statsvetenskapliga institutionen.

Steenbergen, Marco R., André Bächtiger, Markus Spörndli, and Jürg Steiner. 2003. Measuring Political Deliberation: A Discourse Quality Index. Comparative European Politics 1: 21–48.

Steiner, Jürg, Markus Spröndli, André Bächtiger, and Marco R. Steenbergen. 2004.

Deliberative Politics in Action: Analysing Parliamentary Discourse. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Stromer-Galley, Jennifer. 2007. Measuring Deliberation’s Content: A Coding Scheme. Journal of Public Deliberation 3(1): article 12. http://www.publicdelib-eration.net/jpd/vol3/iss1/art12/ [accessed March 10, 2014].

Sunstein, Cass R. 2000. Deliberative Trouble? Why Groups Go to Extremes. Yale Law Journal 110(1): 71–119.

Th omas, John Clayton, and Julia E. Melkers. 2001. Citizen Contacting of Municipal Offi cials: Choosing between Appointed Administrators and Elected Leaders. Journal of Public Administration Research and Th eory 11(1): 51–72.

Th omas, John Clayton, and Gregory Streib. 2003. Th e New Face of Government: Citizen-Initiated Contacts in the Era of E-Government. Journal of Public Administration Research and Th eory 13(1): 83–102.

Th ompson, Dennis F. 2008. Deliberative Democratic Th eory and Empirical Political Science. Annual Review of Political Science 11: 497–520.

Van der Meer, Tom W. G., and Erik van Ingen. 2008. Schools of Democracy. Disentangling the Relationship between Civic Participation and Political Action in 17 European Countries. European Journal of Political Research 48(2): 281–308.

Wildavsky, Aaron. 1979. Speaking Truth to Power: Th e Art and Craft of Policy Analysis.

New Boston: Little, Brown.

Appendix Overview of the Coding Scheme

Variable Measure Description

Continuation Yes/no Is it the author’s response to municipality’s answer? Continuation of communication

Actor 1 to 6 Who sent the document?

1 = One individual or family 2 = Ad hoc group (e.g., parents)

3 = Social movement/civil society organization 4 = Interest group

5 = Enterprise 6 = Other

Format Complaint Longer document that clearly states that something is wrong with current practice/regulations or points to some new issue(s)

Outcry Short document that only states some position (e.g., “Do not close our school” or “Give computers to all students”) Question Author requires information about something

Other None of the above (e.g., letters that praise teachers)

Issue Physical environment The statement refers to physical environment (buildings, equipment, etc. (including all cases of school closure or changes in school organization)

Psychological environment The statement refers to psychological environment (teachers’ behavior, bullying, discomfort due to too many children in a group, etc.)

Benefi ts/entitlements The statement refers to services (transport, fees, “right to a place in daycare”) the municipality is expected to provide

Other None of the above

Aim Daily activities/regulations Problems bureaucrats can solve on a day-to-day basis (questions on leaking roofs, squeaking doors, etc. Decision procedure Refers to decision-making procedure

Legal mistake Refers to some legal mistake that municipality has made Made decision Refers to decision municipality has already made Made proposal Refers to proposal municipality has presented

Other None of the above

Tone Upset Author is clearly upset or angry

Aggressive Includes any threat, swearwords, or unpleasant personal statements.

Formal Text is very polite/formal

Other None of the above

Argument Simple Arguments in support of the expressed opinion are few and simple

Informed Author uses some more elaborated argument (uses sources like own calculations, newspapers, research) to support an opinion

Alternative Constructive politics: puts forward some alternative solution(s) that is not completely unrealistic or otherwise unthinkable

Open to change Humble (e.g., “I might be wrong,” open to different opinion) Source of

information

1 to 7 1 = Personal experience

2 = Own simple investigation

3 = Own advanced investigation (calculations, legal investigation, etc.) 4 = Scientifi c resources (reports, articles)

5 = Media sources (newspapers) 6 = Offi cial documents (e.g., Skolverket) 7 = Other (anything else)

Frame Personal interest Issue is framed as mainly important for the author

Group or close community Issue is framed as mainly important for other(s) in the community (parents, pupils) Municipality Issue is framed as of interest for the municipality