On J¨urgen Habermas and public relations

Roland Burkart

∗Department of Communication, Vienna University, Austria

Received 17 February 2007; received in revised form 7 May 2007; accepted 11 May 2007

Abstract

Habermas focuses on the human communication process with understanding in mind. Here it is argued that this perspective is also worth to be considered for the field of public relations research. The article points out how to apply Habermas’ concept of understanding for the purposes of evaluation as well as for the purposes of planning public relations communication.

© 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: J¨urgen Habermas; Understanding; Theory of communicative action; Consensus Oriented public relations

1. Introduction

A central effort of Habermas’ thinking is to reconstruct universal conditions of understanding within the human communication process. A major issue in this context is semiotics and its well-known dimensions syntactics, semantics, and pragmatics (Morris, 1938). While syntactics deals with the grammatical rules for concatenating signs, semantics refers to the aspects of meaning that are expressed in a language. The pragmatic perspective – the third component – focuses on the relation of signs to interpreters. This is where the “speech act-theory” (Austin, 1962; Searle, 1969) starts, that assumes that to speak a language is, at the same time, a way of human acting. In his main work,How to do things with Words,Austin (1962)questions, what we do when we use our language, and concludes that we create speech acts. We make assertions, give orders, ask questions, make promises, etc. Speech acts are seen as the smallest units of verbal communication.

This exactly is the point where J¨urgen Habermas sets in with hisTheory of Communicative Action (TCA)(Habermas, 1984, 1987). In this seminal work he analyzes the conditions of the human communication process by means of an examination of speech-acts because he views language as the specifically human means of understanding. “Reaching understanding’ ’– according to Habermas – is the “inherent telos of human speech” (Habermas, 1987, p. 287).

As a philosopher, Habermas intends to make “understanding” (and thus communication) discernable as a funda-mental democratic process. He wants to demonstrate that, as a measure for the solution of social conflicts, violence can be replaced by the rational consensus of responsible citizens. From the perspective of communication theory, he therefore infers a number of rational conditions for mutual understanding in communicative action (Habermas, 1984, pp. 305–328).

My intention is to utilize this aspect of Habermas’ theory for public relations research. This is not really a new idea. There have been several attempts to employ the Habermasian communication theory for public relations. In those

∗Tel.: +43 4277 49323; fax: +43 4277 49388. E-mail address:roland.burkart@univie.ac.at.

250 R. Burkart / Public Relations Review 33 (2007) 249–254

cases, however, the issue mainly was to transfer the ideal type conditions of the dialogue onto the public relations process, and to formulate, based upon this context, “an ethical imperative for public relations” (Pearson, 1989a, p. 127) or, respectively, the necessary conditions for ethical public relations (Pearson, 1989b).1Similar ideas can be found in more recent publications, too. For example,Leeper (1996)points out the importance of the study of public relations ethics;Meisenbach (2006)develops “five steps of enacting discourse ethics” (p. 46) using Habermas’s theory as a moral framework for organizational communication.

This article, however, focuses neither on ethical principles nor on morally based directives. Nor will I try (naively) to adopt the Habermasian principles of understanding directly onto the reality of public relations. Rather the aim of my approach is to gain suggestions for the analysis of real public relations communication from the perspective of Habermas’s concept of understanding. In particular, one can use this perspective to illumi-nate the relation between public relations experts offering information and members of target groups who receive this information. As a result of this attempt a so-called “Consensus-Oriented Public Relations” (COPR) approach for planning and evaluating public relations-communication has been established (Burkart, 1993, 1994, 2004, 2005).

The practical background is that especially in situations with a high chance of conflict, companies and organizations are forced to present good arguments for communicating their interests and ideas—in other words: they must make the publicunderstandtheir actions. Therefore, in the view of COPR, understanding plays an important role within the public relations management process.

2. The perspective of understanding in Habermas’sTheory of Communicative Action

According to theTheory of Communicative Action(Habermas, 1984, 1987), communication always happens as a multi-dimensional process, and each participant in this process needs to accept the validity of certain quasi-universal demands or claims in order to achieve understanding.

This implies that the partners in the communication process must mutually trust that they fulfill the following criteria:

- intelligibility (being able to use the proper grammatical rules),

- truth (talking about something the existence of which the partner also accepts), - trustworthiness (being honest and not misleading the partner),

- legitimacy (acting in accordance with mutually accepted values and norms).

As long as neither of the partners have doubts about the fulfillment of these claims, the communication process will function uninterruptedly.

However, these ideal circumstances are an ideal type of imagination—hardly ever they occur in reality, Habermas argues. Often, basic rules of communication are violated and therefore there is a certain “repair-mechanism” which is called the discourse. The term “discourse” used by Habermas means that all persons involved must have the opportunity to doubt the truth of assertions, the trustworthiness of expressions and the legitimacy of interests. Only when plausible answers are given, the flow of communication will continue.

Basically, Habermas distinguishes three types of discourse (seeFig. 1):

• In an “explicative”discoursewe question the intelligibility of a statement, typically by asking “How do you mean

this?”, or “How shall I understand this?” Answers to such questions are called “interpretations”.

• In a “theoretical”discoursewe question the claim of truth, typically by asking “Is it really as you said?”, or “Why

is that so?” Answers to such questions are called “assertions” and “explanations”.

1 These conditions involve the communicators understanding and satisfaction with rules concerning (1) “opportunity for beginning and ending

Fig. 1. Claims and types of discourses according to J¨urgen Habermas’ theory of communicative action.

• In a “practical”discoursewe question the normative rightness (legitimacy) of a speech-act by doubting its normative

context, typically by asking “Why have you done this?”, or “For what reason didn’t you act differently?” Answers to such questions are called “justifications” (cf.Habermas, 1984, p. 110).

A fourth aspect, i.e. the claim of trustworthiness (typical questions: “Will this person deceive me?”, “Is he/she mistaken about himself/herself?”), is an exception as it cannot be subject to discourse because the communicator can prove his truthfulness only by subsequent actions (Habermas, 1984).

Discourses must be free of external and internal constraints. However, this is what Habermas calls “contrafactual” because the “ideal speech situation” that would be required for this does not exist in reality. We only act as if it would be real in order to be able to communicate (Habermas, 1984, p. 180).

The process of “understanding” is not an end in itself. Normally we pursue the intention of putting our interests into reality. Thus understanding becomes the mean for the coordination of actions, as the participants involved in this process aim at synchronizing their goals on the basis of common definitions of a situation (Habermas, 1984).

This leads to the conclusion that commonly accepted definitions of a situation need undisturbed processes of understanding as a prerequisite for deciding about what should be done in a given case.

3. Public relations as a process of understanding

The COPR model focuses on the above prerequisites. Public relations managers who reflect on the basic principles of communication will always orientate their activities in accordance with possible criticism maintained by the public. However, the COPR model is not a naive attempt to transfer Habermas’ conditions of understanding directly onto the reality of public relations—although this was (wrongly) insinuated in the past by some German critics.2In view of

the theory’s contrafactual implications this would be inadequate. It was rather a goal to gain from Habermas’ concept of understanding new ideas for the analysis of real public relations communication. The main impact of creating the COPR-model was the possibility in differentiating communicative claims, so that this process of questioning can now be analyzed more systematically.

Especially in situations when conflicts are to be expected public relations managers have to take into account that their messages might be questioned by critical recipients. Members of the publics involved will offer their doubts about the truth of presented public relations information, especially when confronted with numbers, other data and

252 R. Burkart / Public Relations Review 33 (2007) 249–254

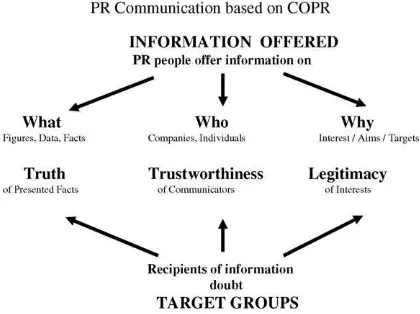

Fig. 2. Public relations communication based on consensus-oriented public relations (Burkart, 2004).

facts. They will question the trustworthiness of the company and its communicators as well as the legitimacy of the company’s interests. This is illustrated inFig. 2.

For example: In case a community plans to build a waste disposal site this will most likely cause disturbance among the local residents. Sometimes even a citizens’ initiative will be formed that aims at bringing down the project. Normally the local media will support the protests so that a conflict situation can be expected.3On the basis of the COPR model

the public relations managers of the company planning the landfill should consider that:

• any assertion they make will be examined concerning its truth, e.g. whether figures about the quantity of waste to

be deposited are correct, whether air, plants, wildlife, ground-water, etc. are really not endangered,

• the persons, companies and organizations involved will be confronted with distrust, e.g. representatives of companies

might be taken as biased, experts/consultants as incompetent or even corrupt,

• their intention for building the landfill will be doubted in principal, either because one questions the basic strategy

for waste disposal (e.g. by preferring waste avoidance as an alternative for landfills), or because the choice of the site for the landfill is seen as unjustified (e.g. because the region has just started developing tourism).

Only if it is possible to eliminate such doubts, or even better, if doubts are prevented from the very beginning, the flow of communication will not be disturbed. However, in reality it will hardly be possible to reach a full consensus or limitless accordance on all three levels of the aforementioned validity claims—not even the TCA itself would imply this. In the present context the it should be mentioned that “rational dissence” is seen by some sociologists of conflict as a major step towards the minimization solution of social conflicts: If we are able to exactly identify the controversial issues, we know the points we have not reached consensus yet. This is the benefit of differentiating several validity claims in the COPR model.

4. Steps and questions for planning and evaluation “Consensus oriented public relations”

In the COPR process four steps with corresponding objectives can be distinguished. These steps must be adapted to the actual conflict situation, in order to use COPR as a planning tool. This makes it also possible to evaluate the success of public relations activities not only in a summative sense (at the end of a public relations campaign) but also in a formative way (this means: step by step).Fig. 3shows in detail the questions that need to be asked in the case of such an evaluation. (“P” stands for planning and “E” for evaluation steps of COPR).

In the case of a planned landfill in Austria the conception of COPR was useful for analyzing and explaining the consequences of the public relations activities that the company launched in the conflict that arose from their

3 A situation of this kind was investigated in Austria in the early 1990s. As a result of that study, the COPR model was developed (cf.Burkart,

Fig. 3. COPR-planning and evaluation.

project (Burkart, 1993, 1994). A representative survey showed that the acceptance of building the landfill correlated convincingly with the degree of understanding. Respondents who tended to accept the project were not only better informed but also less likely to question the trustworthiness of the planners and the legitimacy of the choice of the site for the landfill.

Nevertheless, the COPR model is all but a recipe for generating acceptance. People cannot be persuaded to agree to a project by pressing a “public relations button” because acceptance can only emerge among the persons involved if the process of understanding has worked successfully. The prerequisite for this is that the need for dialogue and discourse on the side of the public is taken seriously by the companies and communication managers concerned, especially when the former feel restricted or even threatened by company interests and plans. In such cases it is nearly a must for companies to communicate with irritated stakeholders—without prejudice to ethical basics or moral rules. Otherwise they will have to postpone or even to cancel their plans. In other words—they “are forced” to communicate in the way outlined above.

254 R. Burkart / Public Relations Review 33 (2007) 249–254 5. Conclusion

In this paper the Theory of Communicative Action (TCA) is used as an analytical framework for the planning and evaluation of public relations in situations of conflict. The focus is on the concept of understanding as defined by J¨urgen Habermas.

With reference to this concept of understanding and an empirical study published elsewhere (Burkart, 1994) a model of Consensus Oriented Public Relations (COPR) has been developed. COPR is a conception for planning and evaluating of public relations. It is based on the assumption that the process of understanding as taking place between public relations clients and publics plays a central role that must not be underestimated. Especially in situations with a potential of conflict this communication process can be disrupted in various ways, i.e., the recipients have doubts about (a) the truth of the messages communicated, (b) the trustworthiness of the communicators involved, and (c) the legitimacy of the interests claimed.

Drawing upon Habermas, in such situations interpersonal communication allows us to induce a discourse (a kind of meta-communication); this is the attempt to re-establish, by reasonable explanation, the inadequate mutual under-standing concerning the truth of the respective assertion(s) and the legitimacy of the interest(s). Accordingly, the COPR model suggests to realize such explanatory activities also for public relations work in individual cases, and to evaluate the results achieved in the understanding process appropriately.

Nevertheless, COPR is certainly not able to prevent that conflicts emerge. Communication alone is not enough to make conflicts vanish into thin air. However, the likelihood that COPR can contribute to the avoidance of the escalation of conflicts is very high. The model, hence, attempts to follow a central idea of Habermas. It intends to point out paths for replacing violence as a measure for the solution of social conflicts by the rational consensus of responsible citizens.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewer for a number of helpful suggestions, and his colleague O.C. Oberhauser for some help with the English version of this paper.

References

Austin, J. L. (1962).How to do things with words. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Burkart, R. (1993).Public Relations als Konfliktmanagement Ein Konzept f¨ur verst¨andigungsorientierte ¨Offentlichkeitsarbeit: Untersucht am Beispiel der Planung von Sonderabfalldeponien in Nieder¨osterreich. Austria: Wien.

Burkart, R. (1994). Consensus oriented public relations as a solution to the Landfill Conflict.Waste Management & Research,12, 223–232. Burkart, R. (2000). Die Wahrheit ¨uber die Verst¨andigung: Eine Replik auf Klaus Merten.Public Relations Forum f¨ur Wissenschaft und Praxis,2,

96–99.

Burkart, R. (2004). Consenus-oriented public relations (COPR): A conception for planning and evaluation of public relations. In B. van Ruler & D. Vercic (Eds.),Public relations in Europe. A nation-by-nation introduction to public relations theory and practice(pp. 446–452). Berlin/New York: Mouton De Gruyter.

Burkart, R. (2005). Verst¨andigungsorientierte ¨Offentlichkeitsarbeit. Ein Konzept f¨ur Public Relations unter den Bedingungen moderner Konflik-tgesellschaften. In G. Bentele, R. Fr¨ohlich, & P. Szyszka (Eds.),Handbuch Public Relations: Wissenschaftliche Grundlagen und berufliches Handeln(pp. 223–240). Wiesbaden, Germany: VS-Verlag.

Habermas, J. (1984).The theory of communicative action. Volume 1. Reason and the rationalization of society. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. Habermas, J. (1987).The theory of communicative action. Volume 2. Lifeworld and system: A critique of functionalist reason. Boston, MA: Beacon

Press.

Jarren, O., & R¨ottger, U. (2005). Public Relations aus. In G. Bentele, R. Fr¨ohlich, & P. Szyszka (Eds.),Handbuch Public Relations: Wissenschaftliche Grundlagen und berufliches Handeln(pp. 19–36). Wiesbaden, Germany: VS-Verlag.

Leeper, R. V. (1996). Moral objectivity, Jurgen Habermas’s discourse ethics, and public relations.Public Relations Review,22(2), 133–150. Meisenbach, R. J. (2006). Habermas’s discourse ethics and principle of universalization as a moral framework for organizational communication.

Management Communication Quarterly,20(1), 39–62.

Merten, K. (2000). Die L¨uge vom Dialog: Ein verst¨andigungsorientierter Versuch ¨uber semantische Hazards.Public Relations Forum f¨ur Wissenschaft und Praxis,1, 6–9.

Morris, C. W. (1938).Foundations of the theory of signs. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Pearson, R. (1989a). Business ethics as communication ethics: Public relations practice and the idea of dialogue. In C. H. Botan & V. Hazelton Jr. (Eds.),Public Relations Theory(pp. 111–131). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.