Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:04

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

A Framework for Teaching Social and

Environmental Sustainability to Undergraduate

Business Majors

Alan L. Brumagim & Cynthia W. Cann

To cite this article: Alan L. Brumagim & Cynthia W. Cann (2012) A Framework for Teaching Social and Environmental Sustainability to Undergraduate Business Majors, Journal of Education for Business, 87:5, 303-308, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.598886

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2011.598886

Published online: 05 Jun 2012.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 214

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.598886

A Framework for Teaching Social and Environmental

Sustainability to Undergraduate Business Majors

Alan L. Brumagim and Cynthia W. Cann

University of Scranton, Scranton, Pennsylvania, USA

The authors outline an undergraduate exercise to help students more fully understand the envi-ronmental and social justice aspects of business sustainability activities. A simple hierarchical framework, based on Maslow’s (1943) work, was utilized to help the students understand, analyze, and judge the vast amount of corporate sustainability materials and publications. The students achieve a deeper understanding of related issues facing organizations, what some organizations have done to date, and what remains to be done. This experience also helps stu-dents to further develop communication and critical thinking skills that can aid the assurance of learning process required by many accreditation bodies.

Keywords: business sustainability, environmental sustainability, undergraduate sustainability education

It is presently almost impossible to teach the principles of management course without a thorough study of sustainable development (SD). A significant number of businesses are infusing SD into their organizations and developing “busi-ness strategies that are intended to add social and environ-mental value to external stakeholders while increasing value to shareholders” (Reed, 2001, p. 3). However, all organiza-tions are not infusing SD at the same rate, at the same level, or with the same focus. Some companies do not engage in sustainability efforts at all, whereas others are dramatically reducing waste, pollution, and addressing social problems. In other cases, forward-looking companies are imbedding SD throughout their organization’s culture.

It is difficult for the undergraduate to understand, assess, compare, and generally make sense of these extremely com-plex business activities. Simple comparisons across corpo-rations are a daunting and sometimes impossible task. This is compounded by greenwashing, or corporations overstat-ing their sustainability efforts to enhance their reputations (Laufer, 2003).

In this article we describe a simple tool based on Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs to allow the student to simplify analyses and more easily sort out corporate SD efforts. Many

Correspondence should be addressed to Alan L. Brumagim, University of Scranton, Kania School of Management, Department of Management/ Marketing, 409 Brennan Hall, Scranton, PA 18510, USA. E-mail: Brumagima1@scranton.edu

students suggest that they can relate more easily to this Maslow-based classification scheme because it just makes sense. Thus, merely framing SD initiatives into alternative categories based on such dimensions as judged level of effort or results often prevent students from making evaluations in a clear, consistent, and defensible fashion. Classroom ex-perience over several semesters has shown that using the Maslow-based hierarchy makes a difference in student en-gagement and learning. Prior to the introduction of this exer-cise many students demonstrated confusion in applying SD concepts during classroom discussions. It must be stressed that this tool aids in critical thinking, but does not result in a single correct answer. The state of present SD informa-tion precludes precise assessment. Still the model allows the student to develop defensible opinions.

Focusing on the classification task allows the student to simplify his or her decision-making process and to better understand SD efforts without becoming overwhelmed and frustrated by the amount, lack of a consistency, and technical nature of much available corporate SD information. The stu-dent is not only able to communicate more clearly, but gains a much deeper appreciation of SD.

The exercise contains several parts. At the beginning of the semester, students are assigned to teams and each team is assigned a company to evaluate. The model is explained to the class and the example of Nike is used to help students become familiar with the hierarchy. The Nike case example suggests a possible loose set of classification criteria and is instrumental in helping students to understand the exercise.

304 A. L. BRUMAGIM AND C. W. CANN

This is a semester-long exercise to allow teams to explore SD efforts of their assigned company in some detail. At the end of the semester each team must present a 10-min presen-tation followed by a 20-min discussion of issues raised (or missing).

THE MODEL AND ITS APPLICATION

To help explain what motivates organizations to move toward SD in different ways, we utilized Maslow’s (1943) five-stage hierarchy of needs. Maslow developed this hierarchy to bet-ter understand human motivation and indicated that the needs must be satisfied in order, from the most basic level to the most advanced. Students are first exposed to the Maslow’s theory from an individual’s motivation perspective. However, we contend that although organizations are not human enti-ties, organizational SD activities can be understood using the same five human needs framework. Maslow himself adapted his hierarchy of needs from his original psychological study of the individual to the broader study of management systems (Maslow, 1998). His levels from the most basic (Level 1) to the most advanced (Level 5) needs are physiological, safety, social, esteem, and self-actualization (Maslow, 1943).

Students are also exposed to the triple bottom line (TBL) in order to provide a context for SD classifications. The TBL is a concept that suggests the interrelationship between peo-ple, planet, and profit, and explains the success of an organi-zation relative to these three factors (Elkington, 1994). This picture of SD not only emphasizes economic prosperity and continuity, but equally recognizes environmental and societal well-being. Successful companies must balance all three. In this article, the TBL concept and the five-level model are used to suggest how students can analyze companies’ SD positions.

A variety of sources can be used in making classifications, including articles, magazines, company publications, and rel-evant nongovernmental organization (NGO) reports. A great deal of information also comes from corporate websites. One hundred percent of the Fortune Global 100 include some type of web-based sustainability or corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting. Although corporate websites have inherent biases, they do provide a wealth of information. They also in-dicate how much the company has assured stakeholders that it is actively engaged in SD, and, to some degree, how much SD is actually infused in operations (Cann & Boock, 2006). Some specific sources of information suggested to students include: the Roberts Environmental Center Evaluations: porate Report Scores, the Global 100 Most Sustainable Cor-porations, and membership in the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD, 2011). Roberts En-vironmental Center Evaluations are particularly useful be-cause they give each company an individual rating, fromAto

F. This gives the student an anchor that increases his or her confidence in the ability to make company classifications.

The hierarchy is intended to make a complex topic as-sessable to undergraduate students. As such, a fine-grained set of evaluation criteria for classifications was deemed to be problematic. Students would just have too much trouble deal-ing with all the possible sources of evaluation criteria that is available. For example, Waddock (2008) identified over 100 sources of information that could help in the assessment of corporate responsibility. Providing this information would certainly overwhelm the student and defeat the purpose of the exercise. The selection of sources listed previously is quite arbitrary; given the plethora of dimensions, any set of classification criteria would be. We intentionally left the cri-teria broad-based to allow the students to make and support their own case. As will be discussed subsequently, this was particularly useful in assessing student critical thinking.

As mentioned previously, students could easily relate to a scheme based on Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs. Yet, other classification schemes have been developed. For ex-ample, Marshall and Toffel (2005) suggested a sustainability hierarchy that is partially based on Maslow’s work. However, they focused on corporate actions rather than positions. It would be very easy for the student to become confused when attempting to synthesize what could be hundreds of corpo-rate actions to make an overall assessment. Other schemes are based on such things as culture (Anderson, Amodo, & Hatzfeld, 2010) or process (Nidumolu, Prahalad, & Ran-gaswami, 2009). These are difficult to use for assessment.

We have found that the exercise outlined in this article overcomes many of these limitations. We now proceed with a discussion of each of the five levels used in the model.

Level 1: Physiological

According to Maslow, at the physiological level the focus is on the requirements for human survival (Maslow, 1998). Level 1 companies are focused almost exclusively on finan-cial performance and growth, sometimes even fighting for survival. In terms of the TBL, economic factors are of pri-mary concern. CEOs and other top managers are under severe pressure. Little meaningful emphasis is placed on social or environmental issues. Level 1 companies are generally un-successful in each of these two TBL dimensions.

Delphi Corporation is an example of a corporation judged to be operating at Level 1, the physiological level. Delphi, af-ter several years of substantial losses and a fight for survival, completed another Chapter 11 reorganization during October 2009 (“Delphi Corporation,” 2011). Delphi was originally a part of General Motors, but became a separate company in 1999. In 2007, losses of $3 billion were incurred on sales

of$19.5 billion. The company had also experienced

signif-icant losses for each of the previous 4 years and has had growing negative equity since 2004. In 2005, Delphi filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. In 2008, due to continuing financial difficulties, Delphi sought additional reorganization under Chapter 11.

During 2009 Delphi achieved near break-even perfor-mance (an$18 million loss) on revenues of$3.4 billion. As

shown from the revenue numbers, Delphi is a much smaller company (Delphi Annual Report, 2009). Roberts Environ-mental Center ranked Delphi as aC(Roberts Environmental Center, 2011). According to this scaleAis the best andFis the worst.

Delphi’s website has an impressive social responsibility section that contains a variety of topics such as diversity, environment, and community. Recently Delphi has put more of an emphasis on SD, which causes some students to assess Delphi as a Level 2 company. Most students consider the con-tinued poor economic performance in placing the company at Level 1.

Level 2: Safety

The second level reflects companies that are engaged in so-cial responsibility and environmental efforts, but only to the degree required by law or in reaction to effective interest groups. According to Maslow (1998), at the safety level the focus is on such things as job security, fair grievance pro-cedures and adequate disability insurance. It is common for Level 2 companies to engage in very minimal sustainable development efforts and instead to engage in public relations efforts regarding sustainability. We contend that Level 2 cor-porations often engage in significant greenwashing. Level 2 corporations generally have achieved some level of economic success, but do not see social and environmental responsibil-ities as important or central parts of their operations.

A historical example of a Level 2 safety company is Royal Dutch Shell Corporation (Shell) just before the Brent Spar production platform disposal controversy in 1995. In terms of financial performance, Shell had more than$2 billion in

profits on rising sales that year (Anonymous, 1995). Shell, one of the largest corporations in the world, faced worldwide attention regarding its planned oil platform dis-posal effort. Shell had planned to sink the Brent Spar plat-form into the sea. Among others, Greenpeace became ac-tively involved in criticizing this plan, taking the position that for environmental reasons the disposal should take place on land. This became a high-pressure issue for Shell. Faced with worldwide criticism and a moratorium on its products, Shell came up with a plan to dismantle the behemoth on land and reuse and recycle much of the platform, but at a sig-nificantly higher cost to the corporation (BBC News, 1998). This is an example of a Level 2 corporation being swayed by outside pressure. Demonstrating only a superficial inter-est in environmental issues and concerned primarily with the safety of the company, Shell was surprised by the level of dissent over its original plans. Shell seemed to have isolated itself from various external stakeholders.

Over the years, Shell has also been criticized for its business-related human rights record, particularly in South Africa and Nigeria, where it has large operations. Many

sug-gest that Shell did not adequately support human rights or help to reduce widespread poverty. Shell seemed to focus on what the country leaders wanted and what was legal in those countries. Although there was public outcry, it was not strong enough to force immediate changes in Shell’s human responsibility position. In response to criticism, Shell con-ducted public relations efforts in an attempt to diffuse public concerns (Levesey, 2001). We contend that Shell was a Level 2 company in 1995.

It should be noted that since 1995 Shell has become more proactive in striving to achieve sustainability. For example, Roberts Environmental Center rated Shell aC+in 2002 and aB–in 2006. Shell is now a member of the WBCSD (2011). The degree to which the Brent Spar incident awakened Shell to a major commitment to SD is an interesting question. Students were able to clearly see the differences between Delphi and Shell, as well as how Shell has changed over time.

Level 3: Social

Maslow (1998) suggested that socialization is not just with people, but with societies and culture as well. He alluded to the lack of alienation and a need to fit with society.

We view fit with society to include the relationship that a corporation has with the many stakeholders who affect or are affected by the company, such as communities and interest groups that are actively pursuing sustainability initiatives. A Level 3 corporation wants to fit well within society because doing otherwise can lead to such negatives as poor reputa-tion, moratoriums on products, and reduced productivity. In addition, the company executives feel that it is the right thing to do. Normally, a Level 3 corporation has a stakeholder management system in place to prioritize and address stake-holders concerns and interests (Savitz & Karl, 2006). A Level 3 company may even have a sustainability evaluation and re-porting system (SERS) to track corporate performance from a stakeholder perspective (Perrini & Tencati, 2006). Level 3 companies have seen the utility and popularity of sustainabil-ity and are struggling with it as a business imperative. In terms of classification, Level 3 companies are actively and visibly committed to sustainability issues, but have just started to commit to sustainability processes, procedures, and prod-ucts. SD efforts that have short-term economic paybacks are particularly attractive to Level 3 corporations. Additionally, top management is just starting to change the organization culture in support of sustainability efforts.

An example of a Level 3 company is the Baosteel Group (a Chinese state-owned corporation), one of the largest steel and iron manufacturers in the world. Profitability based on discipline and the quest to produce the highest quality prod-ucts permeates the company culture (Baosteel, 2011).

Yet, in order to become a world class company, something that many Chinese companies want to achieve, Baosteel re-alizes the need to focus on SD, not just economic growth.

306 A. L. BRUMAGIM AND C. W. CANN

With this in mind, specific SD goals and initial SD system processes have been established. As one example, research and development efforts to enhance steel-making by reduc-ing energy use and minimizreduc-ing or recyclreduc-ing production waste are a priority.

One of the largest subsidiaries of Baosteel, Baoshan Iron & Steel Company, is the first enterprise among China’s do-mestic metallurgical companies to receive the ISO14001 certification. Other divisions have recently achieved or are working hard to achieve this certification. The air quality around the main Shanghai plant has reached the standard of a state-level scenic spot. Baosteel is a member of the WBCSD (2011).

The corporation understands the importance of environ-mental issues within the context of significant environenviron-mental challenges facing the People’s Republic of China and has initiated many environmental systems.

We consider Baosteel to be a Level 3 company because of its recognition of the importance of SD efforts and its many measureable SD initiatives that are at least in the preliminary stage. This example also exposes students to the considera-tion of differences among countries and cultures. Although we use Baosteel as an example of a Level 3 company, the rating was taken within the context of the People’s Republic of China’s economic and environmental condition. Students debate whether the classification should be country-specific or universal. This is an important learning experience.

Level 4: Esteem

According to Maslow, at the esteem level the respect need has been satisfied (Maslow, 1998). Companies in this cat-egory are seen as having implemented substantial sustain-ability systems, developed a competitive advantage (Lee & Ball, 2003), and are held out as examples to follow. These companies are very proud of their sustainability efforts and continue to see advances in sustainability as a central aspect of their strategy. The TBL has been or is close to being in balance. Substantial revenue-enhancing and cost-saving SD efforts are typical at this level.

An example of a Level 4 company is General Electric Corporation (GE) under Jeff Immelt. There is an increased and serious emphasis within GE on corporate citizenship in its various forms. GE sees SD as a great opportunity not only for cost savings, but particularly for revenue generation, as new green products and services are widely introduced into the marketplace. GE’s efforts in wind technologies are one example. “GE is deploying the biggest and most ambitious climate strategy in corporate America,” said Eileen Claussen, president of the Pew Center on Global Climate Change, “and is taking an incredibly gutsy stand in favor of greenhouse-gas regulations” (Griscom Little, 2006, p. 2). Focusing all of these efforts, GE has introduced the ecomagination program and has recently announced that it is expanding its strategy and goals:

GE’s corporate citizenship strategy is defined by three key pillars of energy and climate change, sustainable healthcare and community building, and underpinned by a foundation of operational excellence in the way that we do business. We highlight our citizenship performance with data points, metrics, [and] actions. (General Electric, 2011)

GE rated aB+from the Roberts Environmental Center’s (2011) corporate evaluation. It is a member of the Business for Social Responsibility Organization (2011), as well as the WBCSD (2011). In terms of overall economic performance in 2009, GE earned more than$11 billion on sales of$156

bil-lion despite the economic recession (General Electric, 2009). It has developed a corporate-based SD esteem.

Students often suggest that GE’s reputation is not without blemish (Natural Resources Defense Council, 2007, March 27). GE has acknowledged responsibility for decades of dumping toxic waste into the Hudson River and for drag-ging its feet for decades in related lawsuits (Mokhiber & Weissman, 2008). Despite these problems, we consider GE, in its present position, to be a Level 4 corporation. However, students must decide and defend the degree to which past actions should affect present classifications.

Level 5: Self-Actualization

Moving on to the highest level, Level 5, Maslow (1998) spent a significant part of his book discussing self-actualization. He saw self-actualization as a complex process to achieve the fullest development of talent. He used the metaphor of the artist, a person striving for perfection in a work that becomes assimilated with the self.

Shifting this concept to a corporation’s quest for sustain-ability, the Level 5 corporation has embedded SD concepts into its corporate identity, as have its employees. Just as an artist continuously strives for perfection with an intense and focused effort, these corporations subscribe to the same ide-als regarding sustainability efforts. Not many corporations have developed a SD position sufficient to merit a Level 5 classification.

A widely used example of a Level 5 corporation is Inter-face, Inc. Interface is the world’s largest commercial man-ufacturer of carpet, modular carpet, carpet tiles, and carpet squares. In 2009 they earned roughly $10 million on just

under$860 in sales (Interface, 2009). Despite two previous

years of losses Interface does not seemed to have decreased its commitment to SD.

Similar to many companies with strong cultures, guiding stories become imbedded in the corporate identity. Their website identified founder and chairman Ray C. Anderson’s moment of insight in 1994, when he became a believer in the need for worldwide sustainability efforts to save the planet (Interface, 2008). One of the company’s top managers was a part of the original team that developed the Leadership in

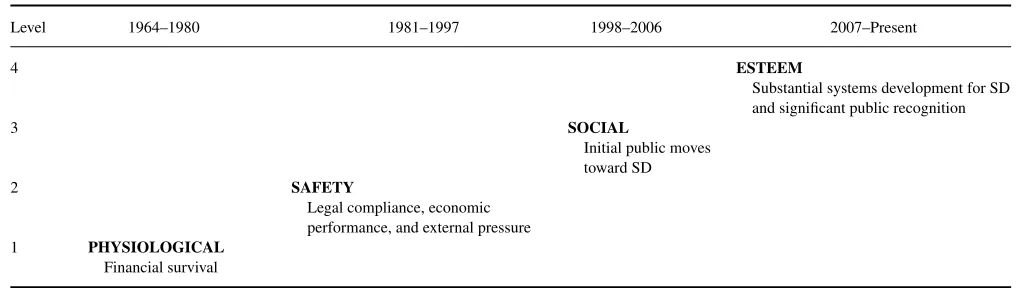

TABLE 1

The Timeline of Nike’s Sustainability Efforts

Level 1964–1980 1981–1997 1998–2006 2007–Present

4 ESTEEM

Substantial systems development for SD and significant public recognition

3 SOCIAL

Initial public moves toward SD

2 SAFETY

Legal compliance, economic performance, and external pressure 1 PHYSIOLOGICAL

Financial survival

Energy and Environmental Design standards widely used for building construction.

The company places a very heavy emphasis on SD initia-tives, metrics, and results. The goals, mission statement, and vision statement all emphasize SD.

THE STUDENT EXPERIENCE

Groups of six students were created in undergraduate intro-ductory management courses. Each group studied the SD efforts of a single preassigned corporation in order to make a decision as to what level of the five-level model their compa-nies had reached. The compacompa-nies selected by the instructors had sufficient data and could reasonably fit into one of the five categories. The purpose of this selection was not to val-idate the model, but to use it as a pedagogical tool to help the student engage in the messy assessment of corporate sus-tainability. The instructors felt that the classification of many of the companies chosen were self-evident. Even so, the stu-dent group rankings agreed with instructor assessments only about 70% of the time. This made for several interesting discussions.

AN EXAMPLE OF A HISTORICAL TIMELINE: THE NIKE CORPORATION

Before starting group assessment work, students were pre-sented with the instructors’ assessment of how Nike might have progressed through the framework levels over time. The time line is shown as Table 1. Note that Nike is presently considered to be a Level 4 corporation.

The analysis and defense of this classification is beyond the scope of this article. It is included here only to show how students can look for and examine differences in SD stages. However, classroom experience has shown that it is too difficult for undergraduate student groups to prepare a similar historical assessment. Thus, this part of the exercise

is in the form of an instructor-led presentation and discussion to acquaint students with the assignment.

ASSURANCE OF STUDENT LEARNING

Our university has undergraduate learning goals related to critical thinking, communication, and environmental and so-cial justice sustainability issues, among others. The exercise discussed in this article can be used to assess all of these skills. Due to space constraints, the importance of the construct, and the difficulty of assessing it, only the critical thinking learn-ing goal will be discussed here.

The learning goals states, “Each student will be skilled in critical thinking and decision-making, as supported by the appropriate use of analytical and quantitative techniques.” This SD exercise is particularly relevant to two learning objectives for the critical thinking learning goal. The first objective is “Students will weigh the significance of key as-sumptions used in business decision-making scenarios.” The student team must weight a variety of information related to its classification of the company of interest. As part of the presentation and classroom presentation students are able to demonstrate the degree to which they can articulate the as-sumptions that they have made. The presentation stage also allows the student team to demonstrate its level of skill for a second assurance of learning objective. This objective states, “Students will defend reasoned solutions to business prob-lems.”

By leaving the sources that the students use to make their assessments somewhat open, this allows for more ef-fective assessment of these critical-thinking objectives. Stu-dents are given a requirement to utilize materials from the popular press. They must decide how to weight information from the company, third-party organizations, and the popular press.

As common in many schools of business, student per-formance related to learning objectives are measured us-ing rubrics. The rubrics used in our school identify three

308 A. L. BRUMAGIM AND C. W. CANN

categories: (a) does not meet expectations, (b) meets expectations, and (c) exceeds expectations. The specific rubrics can be obtained from Alan L. Brumagim. These rubrics are learning goal-related rather than class or exercise-related. Over the last three years more than 80% of the teams met or exceeded expectations. More than 30% exceeded ex-pectations.

Although the instructors question individual team mem-bers during in-class presentations, the assessment is ulti-mately a team rather than an individual assessment. This is not adequate for most accreditation bodies such as the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business In-ternational. Classroom experience to date has demonstrated the utility of this exercise and it future use as an individual class-embedded assurance of learning tool. Furthermore, it lends itself to use as a schoolwide assessment experience where outside business people evaluate the degree to which individual students meet the critical thinking learning objec-tives. There external assessment mechanisms are presently in place.

CONCLUSION

We have outlined an exercise that helps the student analyze and synthesize the very complicated issue of assessing corpo-rate environmental and social responsibility. During student presentations it was clear that they had been exposed to many SD concepts, opinions, and facts for the first time. It is our contention that by keeping things simple the students were not overwhelmed by the complexity of the topic. Addition-ally, the exercise has great potential for assessing multiple assurance of learning goals. But perhaps most importantly, many students became more interested in SD issues, in no small part by evaluating what some corporations are doing. Examination of a Level 1 corporation seems as revealing as the examination of a Level 5 corporation.

REFERENCES

Anderson, R., Amodeo, M., & Hartzfeld, J. (2010). Changing business cultures from within. In The Worldwatch Institute: 2010 State of the World(pp. 96–102, 213–214). Washington, DC: Worldwatch Institute. Anonymous. (1995, May 12). International briefs: Royal Dutch/Shell

reports surge in profit. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1995/05/12/business/international-briefs-royal-dutch-shell-reports-surge-in-profit.html

BBC News. (1998, November 25).Brent Spar gets chop. Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/221508.stm

Baosteel. (2011). Baosteel sustainability. Retrieved from http://www. baosteel.com/plc e/05development/ShowArticle.asp?ArticleID=29 Business for Social Responsibility. (2011).Member list. Retrieved from

http://www.bsr.org/membership/member-list.cfm

Cann, C. W., & Boock, N. M. P. (2006). Is CSR reporting just reputation assurance or is there more to it?International Journal of Environmental, Cultural, Economic and Social Sustainability,1, 141–149.

Delphi Annual Report. (2009). Retrieved from http://delphi.com/pdf/about/ financials/2009-Delphi-consolidated-financial-statements.pdf

Delphi Corporation. (2011, January 11).The New York Times. Retrieved from http://topics.nytimes.com/top/news/business/companies/delphi-corporation/index.html.

Elkington, J. (1994). Toward the sustainable corporation: Win-win-win busi-ness strategies for sustainable development.California Management Re-view,36(2), 90–100.

General Electric. (2009).GE 2009 annual report. Retrieved from http:// www.ge.com/ar2009/pdf/ge ar 2009 financial section.pdf

General Electric. (2011).Citizenship. Retrieved from http://www.ge.com/ company/citizenship/index.html

Griscom Little, A. (2006, July 10). GE’s green gamble. Vanity Fair. Retrieved from http://www.vanityfair.com/politics/features/2006/07/ generalelectric200607

Interface. (2008). Company history. Retrieved from http://www. interfaceglobal.com/Company/History.aspx

Interface. (2009).2009 Annual report. Atlanta, GA: Author. Retrieved from http://phx.corporate-ir.net/External.File?item=UGFyZW50SUQ9NDc2 NDZ8Q2hpbGRJRD0tMXxUeXBlPTM=&t=1

Laufer, W. S. (2003). Social accountability and corporate greenwashing.

Journal of Business Ethic,43, 253–261.

Lee, K.-H., & Ball, R. (2003). Achieving sustainable corporate competitive-ness: Strategic link between top management’s (green) commitment and corporate environmental strategy.Greener Management International,

44, 89–104.

Levesey, S. M. (2001). Eco-identity as discursive struggle: Royal Dutch/Shell, Brent Spar, and Nigeria.Journal of Business Communi-cation,38(1), 58–91.

Marshall, J. D., & Toffel, M. W. (2005). Framing the elusive concept of sus-tainability: A sustainability hierarchy.Environmental Science and Tech-nology 39(3), 673–682.

Maslow, A. (1943). A theory of human motivation.Psychological Review,

50, 370–396.

Maslow, A. (1998).Maslow on management.New York, NY: Wiley. Mokhiber, R., & Weissman, R. (2008).You don’t know jack. Retrieved from

http://www.cleanupge.org/youdontknowjack.html

Natural Resources Defense Council. (2007).Historic Hudson River cleanup to begin after years of delay, but will General Electric finish the job?

Retrieved from http://www.nrdc.org/water/pollution/hhudson.asp Nidumolu, R., Prahalad, C. K., & Rangaswami, M. R. (2009, September).

Why sustainability is now the key driver of innovation.Harvard Business Review, 57–64.

Perrini, F., & Tencati, A. (2006). Sustainability and stakeholder manage-ment: The need for new corporate performance evaluation and reporting systems.Business Strategy and the Environment,15, 296–308. Reed, D. J. (2001).Stalking the elusive business case for corporate

sustain-ability. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

Roberts Environmental Center. (2011). Report list. Retrieved from http://www.roberts.cmc.edu/PSI/ReportList3.asp

Savitz, A., & Karl, W. (2006). The triple bottom line: How today’s best-run companies are achieving economic, social, and environmental success—and how you can too. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Waddock, S. (2008).Building a new institutional infrastructure for

corpo-rate responsibility. Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative, Working Paper No. 32. Cambridge, MA: John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University.

WBCSD. (2011). Membership. Retrieved from http://www.wbcsd.org/ web/about/members.html