Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Increasing Creativity in Economics: The Service

Learning Project

Aref Hervani & Marilyn M. Helms

To cite this article: Aref Hervani & Marilyn M. Helms (2004) Increasing Creativity in Economics: The Service Learning Project, Journal of Education for Business, 79:5, 267-274, DOI: 10.3200/ JOEB.79.5.267-274

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.79.5.267-274

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 47

View related articles

ith only 23% of instructors requiring term papers in upper level courses and only 11% requiring shorter papers (Becker & Watts, 1996), economics students do relatively little writing in their economics courses. Term papers are required in only 12% of the principles of economics courses, and this requirement, surprisingly, does not vary with class size (Siegfried & Kennedy, 1995). Research in economic education suggests that this lack of writing is a limitation of current eco-nomic instruction (Anderson, 1992; Salemi, Siegfried, Sosin, Walstad, & Watts, 2001). A more creative teaching method based on classroom interaction can lead to a more effective delivery style that would improve instructional education in intermediate and upper level economic courses. In this article, we discuss the implementation of ser-vice learning projects as a way to both improve teaching and motivate students to write more papers.

Service learning projects expand teaching and learning beyond class-room activities by relying on more practical applications (Berson, 1994; Giles & Eyler, 1994; Kinsley, 1993). Service learning has been applied in a wide variety of disciplines and courses, including writing and composition (Adler-Kassner, Crooks, & Waters,

1997), finance (Dahlquist, 1998), engi-neering (Kvam, 2000), psychology (Wilson, 2003), science and mathemat-ics (Duke, 1999; Mogk & King, 1995; Ostroff, 1996), accounting (Cruz, 2001), nursing (Narsavage, Lindell, Chen, Savrin, & Duffy, 2002) Spanish (Plann, 2002), political science (Rob-bins, 2001), and liberal education (Bat-tistoni, 1995; Bloom, 2003; DeVitis, Johns, & Simpson, 1998; Huckin, 1997; Sigmon, 1996) courses.

An instructor’s objective should be to help students develop proficiencies in economics. Proficiencies refer to the ability to combine subject matter knowledge and a set of complementary skills in ways that go beyond classroom

assignments and examinations. By the time of their graduation, economics majors should have a developed set of proficiencies. Hansen (1986) proposed the following five proficiencies, each embracing progressively higher levels of cognitive skill:

1.Accessing existing knowledge.The graduate should be able to locate pub-lished research in economics and relat-ed fields, find information on particular topics and issues in economics, and search out economic data as well as information about the meaning of the data and how they were derived.

2.Displaying command of existing knowledge. He or she should be able to write a review of a published journal article, summarize in a 3-minute mono-logue or a 200-word written statement what is known about the current condi-tion of the economy, summarize the principal ideas of a leading economist, summarize a current controversy in the literature, state succinctly the dimen-sions of a current economic policy issue, and explain key economic con-cepts and describe their use.

3.Interpreting existing knowledge. The economics graduate should be able to explain the economic concepts and principles used in economic analyses appearing in daily newspapers and

Increasing Creativity in Economics:

The Service Learning Project

AREF HERVANI MARILYN M. HELMS

Dalton State College Dalton, Georgia

W

ABSTRACT.In this study, the authors analyze an effective classroom teach-ing style that relies on interactive learn-ing and integrates classroom activities and efforts into communities. They introduce the service learning project as an effective teaching tool that can be used along with other effective teach-ing practices to enhance students’ learning outcomes. The authors found that the success of the service learning project is affected by the degree of inte-gration among the institution and the public and private community agen-cies. Through such integration, both the students and the community receive greater benefits from increased knowl-edge and joint activities.

weekly magazines; read and interpret a theoretical analysis, including simple mathematical derivations reported in an economics journal article; and read and interpret a quantitative analysis, includ-ing regression results, reported in an economics journal article.

4.Applying existing knowledge. He or she should be able to prepare a written analysis of a current economic problem as well as a two-page decision memo-randum for a superior that recommends an action on an economic decision faced by the organization.

5.Creating new knowledge.The grad-uate should be able to identify and for-mulate a series of questions that will facilitate investigation regarding an eco-nomic issue, prepare a five-page propos-al for a research project, and complete a research study and report the results in a 15-page paper.

In this article, we propose assigning a student paper or service learning project as a way to address these knowledge deficiencies. Service learning involves students in a wide array of diverse activ-ities that benefit all the students and use the experiences generated to enhance learning, provide the student with a deeper understanding of the course con-tent, and enhance the student’s sense of civic responsibilities and/or civic lead-ership (Bringle & Hatcher, 1996; Water-man, 1997).

Service learning addresses three pro-ficiencies mentioned above—numbers 1, 2, and 4—in detail and often will address all five proficiency areas. Ser-vice learning also meets the curricular need for more writing and application in economic courses. Becker (1997) called for new research on the relative merits of multiple-choice and essay tests; on the lasting effects of course work in eco-nomics; and on the effects of instruc-tors, instructional techniques, and new technologies on student learning. Beck-er (1999), Watts (2000), and BeckBeck-er and Watts (2001) suggested that lecturing is far too passive to engage learners and called for other techniques to help stu-dents become more active in learning. Service learning is a way to make the on-campus classroom a more active experience and appeal to students’ inter-est by being more relevant.

The Need for Creativity in Economics

In learning theory, higher levels of understanding require active involve-ment in application and use of concepts (Becker, Highsmith, Kennedy, & Wal-stad, 1991). Active involvement in the learning process seems to help, particu-larly when students are learning how to solve complex problems. In addition, case learning or other applied learning offers opportunities for repetition and reinforcement of concepts already stud-ied, thereby increasing the likelihood of retention (McKeachie, 1999). Students enjoy real-life examples and develop a greater appreciation for the relevance of concepts. Actual current economic events are brought into the classroom to help fill gaps created by students’ lack of real-world experience. As a result, the motivation to learn may be enhanced (Bonwell & Eison, 1991). Fels and Buckles (1981) proposed three main objectives to courses in economics: to master economic principles, to acquire skill in applying the principles to reali-ty, and to learn to analyze policy issues systematically.

Service learning, including the case method, presents real-world problems in which students are expected to apply the theoretic knowledge and analytical methods that they have acquired. Cases and real-time events contain informa-tion that is not only diverse and interest-ing but also relevant to the business environment where graduates will be working (Buckles, 1999). Such activi-ties convey information about qualita-tive trade-offs and complex environ-ments. Hansen (1999) stated that students are developing important skills that help them function more effectively in the labor market or in graduate school, even though those skills are not always measured by exam scores or course grades.

Two significant themes for teaching college-level economics are adaptabili-ty of course content and stimulation of student learning—both goals of service learning. First, classroom experiments are effective because students are placed into the economic environments being studied. Good teachers under-stand, perhaps intuitively, that to

achieve deep, lasting learning, students need to be engaged on many levels— emotional, physical, spiritual, and cog-nitive (McLeod, 1996). Teaching should incorporate diverse methods that engage students in personal exploration and help them connect course material to their own lives.

Second, there are several ways to enhance students’ learning when the major constituent is their own willing-ness and participation. The students’ learning process also can be enhanced through the resources provided by the instructor or the institution to increase student learning experiences. Addition-ally, the degree of integration among the business, community, and institu-tion plays a major role in enhancing students’ learning and transferring the classroom knowledge into the business community.

Students’ willingness to participate in classroom activities or engage in outside activities relevant to the course can enhance learning outcomes. The instruc-tor plays an important role in providing students with opportunities to expand their classroom learning through com-munities. The integration of students’ learning into the community not only provides the students with practical hands-on experience but also benefits the society as a whole by using student or human capital produced by the acad-emic institutions.

The institution’s efforts to provide ease of movement between the class-room and community can encourage the instructors to participate in these pro-grams and to implement projects that enhance student learning. The institu-tions should play a greater role in identi-fying the community needs and the opportunities to work with businesses. Resources devoted to such activities can lead to accumulated knowledge over time and gradual development of the infrastructure to absorb such integration.

Seldom do the traditional teaching styles used in most institutions encour-age learning beyond the classroom. Yet, educational institutions must meet the increasing expectation on campus and in the community for integration of student learning and community needs in the interest of resolving America’s social problems (Jacoby, 1996). We believe that

enhancement of the student’s learning process can be achieved when the institu-tions play a greater role in providing the necessary resources and incentives that make such integration possible. One way that institutions can accomplish this is through community service learning and adaptation of the service learning peda-gogy (Berson, 1994).

Working with community resources can include a variety of organizations. For example, organizations that are working with area problems can include homeless shelters, after-school pro-grams (Big Brothers/Big Sisters, Junior Achievement, Girl’s Inc.), urban plan-ning groups (city councils, planplan-ning and zoning boards, county commissions), abuse centers (family and children’s ser-vices, crisis center, community kitchen), and other public or private agencies. The Service Learning Center at the aca-demic institution or a similar outreach department should take the initiative to make contacts with these and other community agencies to identify their needs (dealing with problems at hand) and build ties to the curriculum by intro-ducing the service learning concept and projects.

Service Learning Pedagogy

The service learning pedagogy inte-grates classroom learning into the com-munity by assigning projects requiring structured reflection that benefits both students and the community (Berson, 1994; Eyler & Giles, 1999; Glenn, 2002; Howard, 1998; Jacoby, 1996; Kinsley, 1994; Mass-Weigert, 1998).

Elzinga (2001) and Eyler, Giles, and Schmiede (1996) commented that an effective teaching style provides an effective learning environment in the classroom and enables students to apply classroom learning to real-life situations. For instance, the goals and objectives for economic faculty mem-bers are to provide students with an understanding of the theoretical foun-dations of economics and also help them develop the necessary skills for analytical thinking. When confronted with real-life situations and problems, students can apply their analytical thinking to comprehend and resolve them. Instructors provide students with

relevant examples and case studies that make a clear connection between theo-retical materials and real economic sit-uations. This goal can be achieved through improvements in the creative and effective aspects of learning and teaching methods.

Because the exact mode of active learning in the classroom can be achieved through several means, the choice is affected by the resource avail-ability. The design and implementation schedule is critical to the success of the assigned student projects and the degree of student learning. At several colleges and universities, students are introduced to service learning through participation in short-term experiences (McCarthy, 1996), providing a balance of challenge and support along with possible future participation in commu-nity service experiences that have more long-term outcomes and in-depth learn-ing (Grauerholz, 2001).

In addition, service learning projects provide the faculty member with an opportunity to conduct action research (Harkavy & Benson, 1998), in which he or she uses the constructed theory, applies it, and further tests it for validi-ty and applicabilivalidi-ty. The action research tends to increase the instructor’s

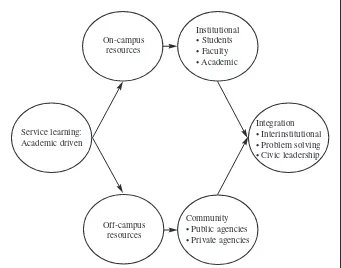

under-standing of teaching and learning and ultimately leads to improvements in his or her classroom practices (Richards & Platt, 1992). Cooperative learning has been found to increase college faculty instructional productivity (Johnson, Johnson, & Smith, 1991). Faculty mem-bers are encouraged by the service learning and find links to the external community that form the basis of teach-ing cases, journal articles, and research streams in addition to increasing the ser-vice component of the instructor’s role. Service learning projects that benefit both the students and the community can best be achieved through integration among institutions, local communities, businesses, government, nonprofit ser-vices, and local groups (Mathews, 1997). Putnam (1993) suggested that state governments should experiment with modest subsidies for training pro-grams to achieve this integration. We illustrate this type of integration in Fig-ure 1. The educational institutions pro-vide the basic skills and collaboration among the parties; however, significant change is needed in the way that most universities view knowledge and how graduates tend to isolate problems in complex human society (Gronski & Pigg, 2000). The integration between

Integration • Interinstitutional • Problem solving • Civic leadership

FIGURE 1. Service learning pedagogy in integration. Service learning:

Academic driven

On-campus resources

Off-campus resources

Institutional • Students • Faculty • Academic

Community • Public agencies • Private agencies

the educational institutions and the pub-lic agencies is more likely to occur with a public institution than a private one. The community college also has a unique opportunity within the service learning paradigm, because the commu-nity college has a greater commitment to improve the communities surround-ing its campuses (Berson, 1994).

The cooperation and integration of the public agencies can lead to greater use of service learning projects in the public institutions and will provide stu-dents with the opportunity to take a leading role in solving the community’s problems. The service learning projects also can be designed to provide support for the business communities and enable them to use the student’s efforts.

The Service Learning Project

Service learning lends itself well to an economics curriculum (Erekson, Raynold, & Salemi, 1996; Freeman, 2001; Hansen, 1986; Holt, 1999;

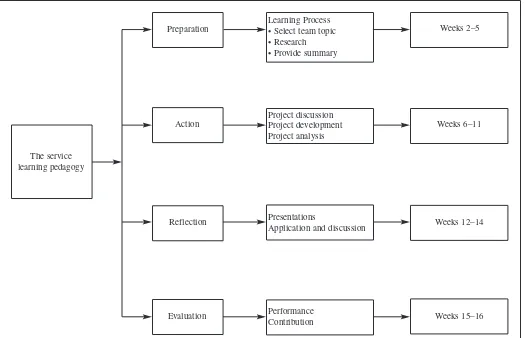

Mankiw, 1998; Marks & Rukstad, 1996) and is more suited to intermediate and upper division courses. The service learning pedagogy has four compo-nents: preparation, action, reflection, and evaluation.

In Figure 2, we break these steps down into weekly activities within a semester in a course incorporating the service learning project. Students are introduced to the project in the course syllabus and receive a project orientation and a handout sheet outlining expecta-tions and project due dates during the 3rd week of a 16-week semester. Prepa-ration and its importance to any success-ful project are stressed. Student teams select a locality or a state and, after ini-tial research, identify a problem facing the selected locality as well as ways to address the problem. The instructor approves topics during the first month of class. The instructor may place students into small teams of three or four mem-bers to complete the project or allow them to choose their own team

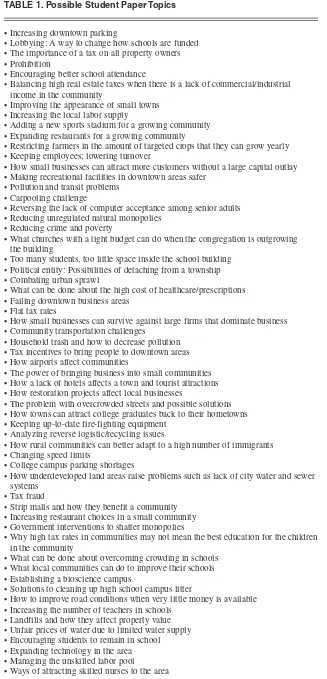

mem-bers. Students are required to write a short paragraph on the chosen social topic (e.g., homelessness, unemploy-ment, literacy, trade embargo, fair trade practices, hunger, labor migration, race issues, feminization of poverty, and women’s issues) that they will investi-gate for the paper project. In Table 1, we list examples of possible paper topics.

Preparation

The implementation of service learn-ing projects will be successful if the institution has developed the infrastruc-ture or has devoted the resources neces-sary to use the projects and pedagogy. In the absence of a dedicated center, the service learning projects may consist only of the preparation phase. If the outreach infrastructure is in place, stu-dents may complete all four stages of the project successfully.

The first phase of the project is the out-line preparation. In the preliminary draft, students are asked to present the problem

FIGURE 2. Service learning pedagogy: Steps and implementation procedure. The service

learning pedagogy

Preparation

Action

Reflection

Evaluation Performance Contribution Presentations

Application and discussion Project discussion Project development Project analysis Learning Process • Select team topic • Research • Provide summary

Weeks 2–5

Weeks 6–11

Weeks 12–14

Weeks 15–16

statement and include a description of the area chosen for investigation. The expanded problem statement describes the situation that the community is facing and includes identifying information on the community, such as name, location, population size, and the potential number of person(s) affected by the issue.

The class uses economic indicators to identify the “problem” in the chosen community and its source. Students describe their project idea for allevia-tion or resoluallevia-tion of the identified prob-lem(s) and explain the goal and purpose of the project. They also specify the methods or steps necessary for achiev-ing the goal and objectives through research, and they state how the goals and objectives of the project can be achieved through use of concepts and theories learned in economics, business, or related disciplines.

The student teams create an action plan outlining the steps needed for investigation of the chosen issue. Stu-dents identify the specific sources of data, types of data (e.g., time series or cross-sectional), and the level of data (e.g., country, state, or city). In addition, they must divide the project by develop-ing a task list identifydevelop-ing group member assignments and milestones required before the due date. Students are made aware that all members must participate actively and equally in the project.

The participating instructors remind students that the assignment is designed to assist them in developing a quality project that potentially could effect sig-nificant social change. Thus, the outline preparation is a first step prior to the “action” or “project development” phase. Preliminary questions, concerns, and comments are addressed in the outline. This part of the preparation phase serves to aid the groups in project achievement. Throughout the semester, students have an opportunity to integrate their learning from the project into class discussions. They are challenged to reflect critically on their topics and proposed solutions.

Action

The second phase of the project is the action plan. In this phase, students famil-iarize themselves with the selected issue by visiting the relevant institutions or

TABLE 1. Possible Student Paper Topics

• Increasing downtown parking

• Lobbying: A way to change how schools are funded • The importance of a tax on all property owners • Prohibition

• Encouraging better school attendance

• Balancing high real estate taxes when there is a lack of commercial/industrial income in the community

• Improving the appearance of small towns • Increasing the local labor supply

• Adding a new sports stadium for a growing community • Expanding restaurants for a growing community

• Restricting farmers in the amount of targeted crops that they can grow yearly • Keeping employees; lowering turnover

• How small businesses can attract more customers without a large capital outlay • Making recreational facilities in downtown areas safer

• Pollution and transit problems • Carpooling challenge

• Reversing the lack of computer acceptance among senior adults • Reducing unregulated natural monopolies

• Reducing crime and poverty

• What churches with a tight budget can do when the congregation is outgrowing the building

• Too many students, too little space inside the school building • Political entity: Possibilities of detaching from a township • Combating urban sprawl

• What can be done about the high cost of healthcare/prescriptions • Failing downtown business areas

• Flat tax rates

• How small businesses can survive against large firms that dominate business • Community transportation challenges

• Household trash and how to decrease pollution • Tax incentives to bring people to downtown areas • How airports affect communities

• The power of bringing business into small communities • How a lack of hotels affects a town and tourist attractions • How restoration projects affect local businesses

• The problem with overcrowded streets and possible solutions • How towns can attract college graduates back to their hometowns • Keeping up-to-date fire-fighting equipment

• Analyzing reverse logistic/recycling issues

• How rural communities can better adapt to a high number of immigrants • Changing speed limits

• College campus parking shortages

• How underdeveloped land areas raise problems such as lack of city water and sewer systems

• Tax fraud

• Strip malls and how they benefit a community • Increasing restaurant choices in a small community • Government interventions to shatter monopolies

• Why high tax rates in communities may not mean the best education for the children in the community

• What can be done about overcoming crowding in schools • What local communities can do to improve their schools • Establishing a bioscience campus

• Solutions to cleaning up high school campus litter

• How to improve road conditions when very little money is available • Increasing the number of teachers in schools

• Landfills and how they affect property value • Unfair prices of water due to limited water supply • Encouraging students to remain in school • Expanding technology in the area • Managing the unskilled labor pool

• Ways of attracting skilled nurses to the area

agencies currently addressing the prob-lem. For example, if the students’ project is to find a possible solution to homeless-ness in their localities, then the students visit a homeless shelter, interview volun-teers and managers, and talk to actual homeless individuals to better under-stand the issue and its current handling. They also may volunteer at the agency. This is particularly effective if communi-ty links have been established previously by the school’s office of service learning. The community service learning coordi-nator usually initiates several sessions with interested faculty members through-out the term to compare experiences and share solutions to common problems. This action stage will include additional Internet and library research.

Reflection

The third phase of the project is reflection. Service learning produces the best outcomes when meaningful ser-vice activities are related to course material through reflection activities such as directed writings, small group discussions, and class presentations. At the completion of the project and before the end of the semester, students are asked to present and discuss their proj-ects in reflection sessions, which pro-vide instructors with the opportunity both to observe and to guide the lessons being learned.

The service learning philosophy pro-vides structured time for students to think, talk, and write about their experi-ences during their service activity. This reflection provides students with a chance to see knowledge acting on real situations in their own communities, further extending learning beyond the classroom. Service learning helps foster the development of a sense of caring for others. It is also a means by which col-leges and universities can promote the civic engagement of students. The reflection process allows students to think about their achievements in the process of service learning and evaluate their contributions to the community.

Evaluation

The fourth phase of the project is evaluation. For this particular

assign-ment, the instructor is the primary eval-uator of the students’ work. He or she judges it according to the approach that the student took to identify and develop a service learning project and identify its possible contributions to the commu-nity. The participating instructors evalu-ate the project according to the guide-lines set forth in the syllabus at the beginning of the project. Other evalua-tors can include the external community groups who potentially will benefit from the findings. Other class members also can evaluate the presentations and provide feedback to both the student team and the instructor on their adher-ence to the project guidelines as well as their in-class delivery.

The Service Learning Center prepares a summary of the students’ reports. Within several weeks after the course ends, the Service Learning Center reviews several critical issues, including the appropriateness of the community sites and the success of service learning activities used in the course.

Paper Presentations and Grading

Student teams present their results in a research format during class. First, general information on the project, such as the community involved, the popula-tion affected, and other relevant demo-graphics, is covered; then students describe the goal and objectives of the project. Next, they present the proce-dures and steps that helped the group achieve the goal, followed by the proj-ect learning objproj-ectives, a summary of the use of economic concepts in offer-ing solutions to the chosen problem, and an explanation of how the textbook con-cepts are reflected in the project.

At completion, the instructors evalu-ate the students’ projects according to the quality of their work—that is, their analysis of the stated problem and their development of a solution. In a macro-economics course, for example, service learning projects receive a grade based on how successfully the student team has (a) used knowledge from the eco-nomics course to analyze the state of the economy (using the economic indica-tors) and (b) tackled the issue at hand by offering solutions at a macro level that make use of the government’s policies.

Short- and Long-Term Benefits

The service learning experience leads to the development of critical thinking skills such as analysis, synthesis, and evaluation (Kinsley, 1994); increased understanding of social problems; the ability to work collaboratively and cre-atively; and, possibly, the development of career goals (Gose, 1997; Jacoby, 1996). Students who participate in ser-vice learning projects acquire valuable lessons from the community that they are serving (Stanton, Giles, & Cruz, 1999). They gain a greater sense of responsibility as members of a commu-nity (Jacoby, 1996) and develop a greater sense of the connection between concepts learned and the challenges offered by a diverse society (Wallace, 2000). The core values of service learn-ing projects are to promote social awareness and caring, responsibility, accountability, critical thinking, creativ-ity, and active learning. They energize classroom learning by motivating facul-ty interest in teaching and student inter-est in the material, and they promote social ethics (Carver, 1997).

As a secondary goal, these projects serve to empower students and promote leadership skills and personal reflection. Students are enabled to make a differ-ence. Moreover, service learning proj-ects serve several parties’ long-term goals: They produce a detailed analysis of complicated social problems and issues; provide students with more knowledge on public and private organi-zations and an expanded outlet to careers; expand the contributions made by institutions to the community; and promote a more efficient integration among educational institutions, the community, and businesses.

Suggestions for Implementation in Other Courses

The service learning projects can encompass various activities, depending on demographics, size of the economy, the locality, the college affiliations or community involvement, the student population, and class size. The projects can be developed as an ongoing process over multiple terms and involve several different student classes. The projects

can be designed for individual students or group work, allowing for the devel-opment of problem-solving skills.

As the service learning projects can be applied in a number of disciplines, interdisciplinary service learning cours-es can be developed. The first step to implementation would be to identify the necessary outlets through which the classroom learning is transferred to agencies dealing with these issues. As an example, medical schools have created trial service learning programs placing beginning students in community sites. These programs take place in the context of a broader relationship between acade-mic medical centers and their surround-ing communities (Schamess, Wallis, David, & Eiche, 2000). Similar transfer-ring of learning easily can be applied to service, social, and business organiza-tions and agencies.

Service learning programs can encompass topics such as the peace and justice studies that integrate community service with course content and require students to work in their local commu-nities. The topics examined can include domestic social justice issues such as inequality, racism, sexism, and econom-ic inequality (Roschelle, Turpin, & Elias, 2000). Through such involve-ments, these programs encourage stu-dents to become political advocates who promote social justice both nationally and internationally.

If integrated into a well-developed program, international service learning programs also can fulfill their potential as a transformational experience for stu-dents by informing subsequent study and career choices. International service learning provides students with the opportunity to work with local organi-zations to serve the community where they are staying, to engage in a cultural exchange, and to learn about a daily reality very different from their own. According to Grusky (2000), interna-tional service learning programs can motivate faculty members to address the huge knowledge gap that exists in inter-national development education.

Areas for Further Research

Future research should examine the degree of community involvement by

various institutions and effective means of furthering this level of integration to foster transfer of knowledge from students to local communities and economies. Research must identify the outlets that institutions and localities will need to take a more responsible role in promoting the transfer of knowl-edge between classrooms and local economies. Other research should con-sider the implementation process with-in the buswith-iness and economics curricu-lum and the evaluation of the benefits versus the time and opportunity costs of these projects.

REFERENCES

Adler-Kassner, L., Crooks, R., & Waters, A. (Eds.). (1997). Writing the community: Con-cepts and models for service-learning in com-position.Washington, DC: AAHE.

Anderson, M. (1992). Impostors in the temple: The decline of the American university. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Battistoni, R. (1995). Service learning, diversity, and the liberal arts curriculum. Liberal Educa-tion, 81(1), 30–35.

Becker, W., Highsmith, R., Kennedy, P., & Wal-stad, W. (1991). An agenda for research on eco-nomic education in colleges and universities. The American Economic Review,81(3),26–32. Becker, W. E. (1997). Teaching economics to undergraduates. Journal of Economic Litera-ture, 35, 1347–1373.

Becker, W. E. (1999). Teaching economics: What was, is, and could be. In W. E. Becker & M. Watts (Eds.),Teaching economics to undergraduates: Alternatives to chalk and talk (pp. 1–10). Chel-tenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, LTD. Becker, W. E., & Watts, M. (1996). Chalk and

talk: A national survey on teaching undergradu-ate economics. American Economic Review, 86, 448–454.

Becker, W. E., & Watts, M. (2001). Teaching eco-nomics at the start of the 21st century: Still chalk and talk. American Economic Review, 91(2), 446–451.

Berson, J. S. (1994). A marriage made in heaven: Community college and service learning. Com-munity College Journal, 64(6), 14–19. Bloom, E. A. (2003). Service learning and social

studies: A natural fit [Electronic version]. Social Education, 17,M4.

Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active learning: Creating excitement in the class-room. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 1. Washington, DC: George Washington University.

Bringle, R. G., & Hatcher, J. A. (1996). Imple-menting service learning in higher education. Journal of Higher Education, 67(2), 221–239. Buckles, S. (1999). Using cases as an effective

active learning technique. In W. Becker & M. Watts (Eds.), Teaching economics to under-graduates: Alternatives to chalk and talk (pp. 225–240). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, LTD.

Carver, R. L. (1997). Theoretical underpinnings of service learning. Theory Into Practice, 36(3), 143–149.

Cruz, A. M. (2001, December). Using service learning to motivate and engage accounting stu-dents. Business Education Forum,34–35. Dahlquist, J. R. (1998). Using service-learning in

finance—A project example. Journal of Finan-cial Education, 24(1), 76–80.

DeVitis, J. L., Johns, R. W., & Simpson D. J. (Eds.). (1998). To serve and learn: The spirit of community in liberal education. New York: P. Lang.

Duke, J. (1999). Service learning: Taking mathe-matics into the real world. The Mathematics Teacher, 92(9), 794–797.

Elzinga, K. G. (2001). Fifteen theses on classroom teaching. Southern Economic Journal, 68(2), 249–257.

Erekson, O. H., Raynold, P., & Salemi, M. (1996). Pedagogical issues in teaching macroeconom-ics. Journal of Economic Education, 27(2), 100–107.

Eyler, J., & Giles, D. E., Jr. (1999). Where’s the learning in service learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Eyler, J., Giles, D. E., Jr., & Schmiede, A. (1996). Practitioner’s guide to reflection in service-learning: Student voices and reflections. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University. Fels, R., & Buckles, S. (1981). Casebook of

eco-nomic problems and policies: Practice in Thinking(5th ed.). St. Paul: West.

Freeman, M. (2001, June). Teaching economics to undergraduates: Alternatives to chalk and talk. Economic Society of Australia, 77,210–212. Giles, D. W., & Eyler, J. (1994). The impact of a

college community service laboratory on stu-dents’ personal, social and cognitive outcomes. Journal of Adolescence, 17, 327–339. Glenn, J. M. L. (2002, April). Building bridges

between school and community: Service learn-ing in business education. Business Education Forum, 56,9–12.

Gose, B. (1997, November). Many colleges move to link courses with volunteerism: Some critics of service learning question the quality of the service and rigor of the learning. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 4,A45.

Grauerholz, L. (2001). Teaching holistically to achieve deep learning. College Teaching, 49(2), 44–51.

Gronski, R., & Pigg, K. (2000). University and community collaboration. The American Behavioral Scientist, 2(43), 781–792. Grusky, S. (2000). International service learning.

The American Behavioral Scientist, 43(5), 858–867.

Hansen, W. L. (1986). What knowledge is most worth knowing—For economics majors? The American Economic Review, 76(2), 149–153. Hansen, W. L. (1999). Integrating the practice of

writing into economics instruction. In W. E. Becker & M. Watts (Eds.),Teaching economics to undergraduates: Alternatives to chalk and talk (pp. 79–118). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Harkavy, I., & Benson, L. (1998). De-platonizing and democratizing education as the basis of ser-vice [Electronic version]. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 73,11–20.

Holt, C. A. (1999). Teaching economics with classroom experiments: A symposium. South-ern Economic Journal, 65(3), 603–610. Howard, J. (1998). Academic service learning: A

counter normative pedagogy. In R. Rhoads & J. Howard (Eds.),Academic service learning: A pedagogy of action and reflection. San Francis-co: Jossey-Bass.

Huckin, T. N. (1997). Technical writing and com-munity service. Journal of Business and Tech-nical Communication, 11(1), 48–59.

Jacoby, B. (1996). Service learning in higher edu-cation: Concepts and practices.San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. A. (1991). Cooperative learning: Increasing col-lege faculty instructional productivity. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 4. Wash-ington, DC: School of Education and Human Development, George Washington University. Kinsley, C. W. (1993). Community service

learn-ing as a pedagogy. Equity & Excellence in Edu-cation, 26(2), 53–63.

Kinsley, C. W. (1994). What is community service learning? Vital Speeches of the Day, 61(2), 40–43.

Kvam, P. H. (2000). The effect of active learning methods on student retention in engineering statistics. The American Statistician, 54(2), 136–140.

Mankiw, G. N. (1998). Teaching the principles of economics. Eastern Economic Journal, 24(4), 519–524.

Marks, S. G., & Rukstad, M. G. (1996). Teaching macroeconomics by the case method. Journal of Economic Education, 27(2), 139–147. Mass-Weigert, K. (1998). Academic service

learn-ing: Its meaning and relevance. In R. Rhoads & J. Howard (Eds.),Academic service learning: A pedagogy of action and reflection.San Francis-co: Jossey-Bass.

Mathews, D. (1997). Changing times in the foun-dation world. A National Civic Review, 86(4), 275–280.

McCarthy, M. (1996). One-time and short-term

service learning experiences. In B. Jacoby (Ed.), Service learning in higher education: Concepts and practices (pp. 113–134). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

McKeachie, W. J. (1999). McKeachie’s teaching tips: Strategies, research and theory for college and university teachers (10th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

McLeod, A. (1996). Discovering and facilitating deep learning states. The National Teaching and Learning Forum, 5, 1–7.

Mogk, D. W., & King, J. L. (1995). Service learn-ing in geology classes. Journal of Geological Education, 43(5), 461–465.

Narsavage, G. L., Lindell, D., Chen, Y., Savrin, C., & Duffy, E. (2002). A community engagement initiative: Service-learning in graduate nursing education. Journal of Nursing Education, 41(10), 457.

Ostroff, J. (1996). Service learning and the envi-ronment meet at Clear Lake. In S. Miller (Ed.), Science and society: Redefining the relation-ship (pp. 13–16). Providence, RI: National Campus Contract.

Plann, S. J. (2002). Latinos and literacy: An upper-division Spanish course with service learning. Hispania (American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese),85(2), 330–338. Putnam, T. (1993). The prosperous community:

Social capital and public life. American Prospect, 13,35–42.

Richards, J., & Platt, H. (1992). Longman dictio-nary of language teaching and applied linguis-tics.Essex, England: Longman Group UK. Robbins, R. (2001). Service learning links

acade-mics to community. Atlanta Business Chroni-cle, 24(20), 13.

Roschelle, A. R., Turpin, J., & Elias, R. (2000). Who learns from service learning? The Ameri-can Behavioral Scientist, 43(5), 839–847. Salemi, M. K., Siegfried, J. J., Sosin, K., Walstad,

W. B., & Watts, M. (2001). Research in eco-nomic education: Five new initiatives. The American Economic Review, 91(2), 440–446. Schamess, A., Wallis, R., David, R., & Eiche, K.

(2000). Academic medicine, service learning, and the health of the poor. The American Behavioral Scientist, 43(5), 793–807. Siegfried, J. J., & Kennedy, P. E. (1995). Does

pedagogy vary with class size in introductory courses? American Economic Review, 85(2), 347–351.

Sigmon, R. L., & colleagues. (1996). Journey to service learning: Experiences from indepen-dent liberal arts colleges and universities. Washington, DC: The Council of Independent Colleges.

Stanton, T., Giles, D., & Cruz, N. (1999). Service learning: A movement’s pioneers reflect on its origins, practice, and future. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Wallace, J. (2000). A popular education model for college in community. American Behavioral Scientist, 43(5), 756–766.

Waterman, A. (1997). Service learning: Applica-tions from the research.Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Watts, M. (2000). Long-term outcomes of learning economics. Research Projects Conference Briefing Paper, Mimeo, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN.

Wilson, H. W. (2003). Service learning and prob-lem-based learning in a conflict resolution class. Teaching of Psychology, 30(3), 260–263.