Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 12 January 2016, At: 23:45

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Schoolwork as Products, Professors as Customers:

A Practical Teaching Approach in Business

Education

Charles R. Emery & Robert G. Tian

To cite this article: Charles R. Emery & Robert G. Tian (2002) Schoolwork as Products, Professors as Customers: A Practical Teaching Approach in Business Education, Journal of Education for Business, 78:2, 97-102, DOI: 10.1080/08832320209599705

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320209599705

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 19

View related articles

Schoolwork as Products,

Professors as Customers:

A

Practical Teaching Approach in

Business Education

CHARLES R. EMERY

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Greenwood, South Carolina

ROBERT G. TlAN

Due West, South Carolina Lander University Erskine College

eaching marketing principles, like

T

teaching almost any principles courses, involves assigning new terms or terminologies to unfamiliar theoreti- cal frameworks and concepts. To accomplish this, professors break down the subject matter into a number of rel- atively distinct subareas for study, such as the four Ps in the marketing mix. Unfortunately, students typically have problems understanding the conceptual linkages between the fundamental com- ponents, although understanding them helps businesses be competitive (Porter, 1980). Thus, practitioners suggest more use of practice-oriented exercises to help students understand the interac- tions between various concepts(Oblinger

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Verville, 1998). Further-more, business supervisors expect their employees to take a systems approach to problem solving (Emery, 2002). In this study, we explored the impact that a practitioner approach might have on

student enthusiasm and learning.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

A marketing principles course offers

several traditional opportunities for experiential learning (e.g., developing marketing plans, conducting focus groups, developing ad campaigns). Though these methods are excellent for helping the students learn various com- ponents of the marketing process, we were looking for something that would pull the whole process together. Hence,

ABSTRACT. The common percep- tion is that only hands-on learning can help students understand the interac- tions between various concepts. In this article, the authors describe a method of teaching the four Ps-product, price, place, and promotion-in a marketing principles course in which the students market their coursework to the professor as the customer. The professor-as-customer paradigm is based on the Japanese Kano model, which identifies and quantifies cus- tomer expectations. In a 2-year exper- iment, they investigated two profes- sors and 357 students and found that

progress occurred on several national- ly normed learning objectives.

we elected to have the students market their work as products to their profes- sors as customers. The students were very enthusiastic when we told them that we were going to help them apply marketing concepts to improve their grades. Specifically, we intended to relate each of the four Ps continuously to the objective of customer satisfaction over the course of the semester. The principal products of this experiment were to be two term projects (one indi- vidual and one team), a team presenta- tion, and a final term paper.

Product: The Schoolwork

A product is a good, service, or idea

that a customer acquires to satisfy a need or want through the exchange of

money or something else of value. Stu- dents learn that their schoolwork can be considered a product because it is of value to the professor (customers). Pro- fessors want to know how much infor- mation is being absorbed by students from resources both inside and outside of the classroom. Students soon realize that by marketing their products to pro- fessors, a mutually beneficial exchange relationship can be established: Profes- sors enjoy seeing students’ learning progress, and students enhance their communication skills and improve their quality of knowledge by responding to professors’ feedback.

In the marketing priciples course described in this article, students come to understand that the foremost goal of marketers is to create and maintain good relationships with their customers (i.e., customer relationship management). Thus, students must strive to build rela- tionships with their professors both inside and outside of the classroom to understand product needs effectively and to communicate product values. Students quickly learn that one must know one’s customers, because the requirements of some customers vary dramatically from those of others. These various product needs translate into various product specifications and opportunities for differentiation. For

example, if a student has a question

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Novernber/Decernber 2002 97

about a project’s instructions, he

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

or she should be encouraged to request clarifi-cation from the professor rather than guessing what the customer needs. This opportunity for a one-on-one exchange can be likened to a minifocus group that energizes the producers by helping them understand the reasons for various requirements. This energy often takes the form of improving product differen- tiation (e.g., features, conformance, aes- thetics, reliability). Furthermore, com- petitors will be constantly striving to imitate a business’s best products, so students must learn to innovate continu- ally and strive for uniqueness. Today’s order winner is tomorrow’s order quali- fier (Hill, 1989). Although one needs to

be aware of the competition, there is far less to fear from outside competition than there is from inside factors such as inefficiency, discourteous behavior, and bad service. One’s own product reliabil- ity is the most influential dimension

(Zeithaml, Berry,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Parasuraman,1988).

Finally, we required students to develop marketing principles and strate- gies based on their perceptions of the professor’s expectation. To accomplish this task, each student first had to per- form market research to determine the customer’s wants and needs. Students realized, as one-person companies, that market research was critical: There were no margins for errors, and they had to hit the bulls-eye the first time because resources (e.g., time) were tight. Sec- ond, the students had to outline their marketing strategies formally according to marketing principles, theories, and empirical research. These strategies often took the form of entertaining as

well as selling and striving to be unique.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Price: The Grade for the Schoolwork

Price is the amount of money or other valuable that the marketer asks for in exchange for a product. The true value of a product, however, is what someone is willing to pay for it. Similarly, the price or value of a student’s product (schoolwork) is reflected in the grade that he or she receives from the profes- sor. Unfortunately, students often per- ceive the grade as a function of the pro-

98

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Journal of Education for BusinessCustomer satisfied

I

I

Dysfunctional Fully functional

I I Customer dissatisfied

FIGURE 1. The Kano model of customer needs.

.--

fessor rather than his or her value cre- ation. An interesting exercise that brings this notion into clearer focus is to have the students place the price or grade on the paper before they submit it to the customer (Emery, 2001a). The better students have a good sense of the value that they create; that is, whether they have met, exceeded, or failed to exceed a professor’s expectations. Over time, this exercise tends to raise the perfor- mance level of the lower performing students because most want to be acknowledged for their accurate self- assessment and few are willing to acknowledge that they are intentionally turning in “C” work.

Additionally, students come to realize that cost is an important aspect of creat- ing value. For example, they must bal- ance their costs and production sched- ules across a variety of customers. Also, they must consider which products are the most important (heaviest weighted) to the consumer. Furthermore, they must examine opportunities for reduc- ing their costs by improving production efficiencies through use of technology,

strategic alliances, and economies of scale and scope.

Place: Handing in Works at the

Desired Location and Time

In the marketing mix, place is a vital aspect of the marketing process through which marketers deliver products to consumers. This factor-product deliv- ery at the desired place and time-has grown in importance as customers expect better service and more conve- nience from businesses. Students have come to realize that this trend also applies to production, delivery (logisti- cal management), and follow-up (cus- tomer service). For example, in busi- ness, logistics management is defined as the process of managing suppliers and the movement of raw materials, parts, work in progress, finished products, and related information through the value chain in an efficient, cost-effective man- ner that meets customer requirements. Students participate in logistics man- agement during the course of each semester. Suppliers are the professors,

support agencies, and other students who provide them with the raw materi- als or knowledge. Parts represent the bundles of knowledge that one uses to construct the product. Work in progress is the partially completed customer orders. Finished products are the papers and presentations produced for grades.

Another aspect of logistics manage- ment is the timely delivery of the prod- uct through marketing channels. Mar- keting channels are extremely important for all marketers because they function in the value chain as a network of part- ners who cooperate to bring products from producers to ultimate consumers. Marketers often opt to use channel part- ners (e.g., other students) because they add value to the marketing process as they complete exchange functions, logistical functions, and facilitation functions. Students realize that their schoolwork may pass through various channels before reaching the consumer and that each of these channels has advantages and disadvantages. For example, the direct channel action of taking schoolwork directly to the pro- fessor's office has the advantage of offering the student the opportunity for making a last-minute sales pitch, but it has the disadvantage of requiring sched- uling of a time in which both parties can meet. Indirect channel actions, such as transmitting the product via email, post- ing the project on a personal student Website, letting others hand in one's schoolwork, or leaving it in the profes- sor's drop-box all offer a certain conve- nience and reduced cost but do not offer the opportunity for face-to-face brand- ing. Most important, however, is the stu- dent's understanding of the customer's desired place and his or her ensuring that it meets the promised due date. Meeting the due date is a customer's basic expectation of the producer's reli- ability. Thus, meeting the deadline does not increase customer satisfaction, but missing it certainly produces customer

dissatisfaction.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I

I

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I I

I

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I /

Promotion: Marketing the Product

Promotion is a vital component of the marketing mix because it informs and educates consumers about the product

I I

E&g!!EE

Qusslion traditional solutions and exammelpresent atha altemativss

Demonnmte critical reasoning and thinkmg.

* Dsmonstratc an integration or analysis beyond the matend given in the textbook. Suggest additional topics far study in L e

m Demonstrare smng malh skills 10 include

Demonstrate bat you can apply learned

-

Use learned concepts 10 propose fheorier.-

Infegrats ~n-clms concepts with I ~ S C learned maids ofelass (psaonal expcrience and other classes).a Pmvide

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

P crealive appmach ID developingROlYtlOOI

COncluSlO" o f answcnlpapen. quantilative methods.

concepts to new IIW1l""l.

0 -

* Organize y o u avwmlpapcr m I

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

lqicalmanner.

Spend enough time on m 8sstgnment 10 ensure quslity a n w e n (w.. time spent IS evident) Provide your mswnptmm when problems do not

pmvide all L e necessary factan to amve 81 a

SOIUtlO".

* Use quantitative skills 10 au~msot answen when sppmprislc (I e , do not avoid the use of malh lo

p r s f y snswcm).

-

Use and undcnland pmper buiinenrtcrmmologylvocabulary

Pmvids detailed mtmnal~ for B N W I F ~ (MI and

p e ~ n s l observalmn).

work).

'discovery learning' tasb (I c , tasks given withoul speeilic directions or examples of required outcomer).

* Cile outside references m B correct manner.

* Seek professor for assistace bg., ofice hours)

* Use rcferencm k y o n d those suggested by the

* Provide accumre ~csula. (Hml Chock your

-

Use all resources available to complete4

0 0

/

Di.ssati.sfactinn 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 @ - / 0 0

Basic needs

/ I I - I I I

I

I* T m in w w k on the due date.

-

Provide profossiwal presenlation ofwork 10 w h d e ~ o n e c l ~pslling and grammar. examples. c h m , fmtnolrr. &

Answer the SPECIFIC quwmnls)

swgnned.

fO"Cl"1IO" or answer

and computer applratmnr formattmg

* Provide all work leading UP lo B

* Demonstrate pmliciency m basic moth

* Cite ouaide refenmen when used

* Follow ~msW~tiom for fomat and

CO"trnt

I

FIGURE 2. Marketing professors' expectations for projectslterm papers.while building a healthy relationship with them through two-way communi- cations. Objectives of promotion include building brand loyalty, provid- ing information, managing demand, and building sales. Central to promotion is the notion of persuasion. Producers must dedicate time for a one-on-one sales pitch to persuade customers that they will fulfill their wants and needs. Furthermore, persuasion is closely linked to the producer's need to differ- entiate his or her product from competi- tors' products; to influence the cus- tomer's perception, attitudes, and behaviors; and to build brand image. This suggests several actions on the part of the students. First, producers must take the time to understand the products and features that the competition offers and to use the best producers to create benchmarks. Second, producers must create a memorable image. For exam- ple, in a large classroom, a professor

inevitably grows weary of reading paper after mediocre paper. However, if a stu- dent uses different techniques and cre- ates a unique product, the professor will be more likely to remember that paper and perhaps grade that student's future work more favorably (i.e., this could create something akin to brand loyalty, which influences customers to overlook minor imperfections in the future).

By implementing promotion theory, students realize that the format of their work is as important as the content, as is the case in the packaging of a real prod- uct. They also agree on the importance of establishing and maintaining good relations with professors. For instance, the student must create a personal repu- tation to ensure that the professor knows

that he or she is dedicated and efficient.

As the ultimate customers of students'

schoolwork, professors must be made aware of the students' dedication and

commitment to superior work. More-

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

November/December 2002 99

[image:4.612.225.565.47.404.2]TABLE 1. Results from the Student Evaluation Survey: IDEA Form

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

QuestionPretest Posttest

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

M/SD M/SD

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(N =

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

338) ( N = 357) Sig. Comment1. Encourages students to use multiple resources to improve understanding

2. Related course material to real-life situations 3. Encourages student-faculty

interaction outside of class (office visits, phone calls, e-mail, etc.)

4. Developing specific skills, competencies, and points of view needed by professionals in the field most closely related to this course

5. Developing creative capacities (writing, inventing, designing, performing, etc.)

6. Developing skill in expressing myself orally or in writing

7. Learning how to find and use resources for answering ques-

tions or solving problems

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

8. Learning to analyze and critically evaluate ideas, argu- ments, and points of view

3.311.2 4.210.7 4.010.6 3.711.1 2.511.2 2.911.1 3.311.1 3.910.9

3.910.9 4.610.6 4.310.5 4.210.6 3.410.9 3.011.2 3.910.8 3.811.0

.001 .001 .001 ,001 .001 .467

.oo

1 .672Hi: T, > Ti supported H,: T, > Ti

supported

H,: T, > T I

supported

H,: T, > T,

supported

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

H,: T, > T,

supported

H,: T, > Ti not supported

H,: T, > T i

supported H,: T, > T I not supported

Note. Questions 1-3 asked the students to rate their professors on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (hardly ever) to 5 (almost always). Questions 4-8 asked students to rate their progress in this course compared with their progress in other courses at the college or university on a 5-point

Likert scale ranging from 1

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(low [lowest 10% of courses I h etaken]) tozyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5 (high [highest 10% ofcourses I have taken]).

over, a successful student should be open to constructive criticism and be willing to change the “product” accord- ing to the professor’s instruction. After all, good producers want to hear com- plaints so that they have the chance to improve and perhaps prevent customer defection.

Customer: The Professor

The primary principle of total quality management suggests that providers should achieve success by understand- ing and satisfying their customers’ needs. As previously suggested, this can

100 Journal of Education for Business

be applied to education through a para- digm in which the professors are the customers (Emery, 2001b). Students become the providers, and it is their responsibility to determine and satisfy customer expectations. It is not enough, however, for the students to understand customer needs or expectations; they must be able to quantify them accurate- ly. All needs are not created equal, and the resolution of a11 needs does not have the same impact on customer satisfac- tion or a project grade (payment).

This concept is easily illustrated through the Kano model (Kano, Seraku, Takahashi, & Tsuji, 1984; see Figure 1).

The Japanese manufacturing industry uses the Kano model to determine and prioritize or weight customer require- ments. The horizontal axis in Figure 1 shows the extent to which customers’ expectations are achieved. The vertical axis shows the customer satisfaction associated with this achievement. Three types of needs are identified in this model: basic needs, satisfiers, and delighters. The first type of expectation, the basic need, is the assumptions that customers have about a service (e.g., the availability of a restroom in a restaurant or error-free spelling on a homework assignment). Though filling these needs does not satisfy the customer, not filling them quickly causes dissatisfaction. The second type of expectation is the satis- fiers, or the list of items that customers would normally mention as keys to their satisfaction (e.g., responsiveness of a server in a restaurant or well-justified recommendations for a case study). Achievement of the satisfiers increases customer satisfaction, but only at a lin- ear rate. The third type of expectation is the delighters, the needs that a customer does not have conscious knowledge of or that fall into the category of “Would- n‘t it be great if someday a student pro- vided..

. .”

Examples of this would be a fine restaurant that provides baby-sit- ting facilities or a student who synthe- sizes material into a new way of looking at things. A provider that does not pro- vide delighters will still have satisfied customers, but those that provide delighters will experience a nonlinear increase in customer satisfaction. The dotted lines graphically depict that all needs are not created equal, and the res- olution of all needs does not have the same impact on customer satisfaction. For example, the additive effect of fail- ing to fulfill basic needs or expectations is a geometric increase in dissatisfac- tion. The additive effect of providing delighters is a geometric increase in sat- isfaction. Lastly, the additive effect of providing satisfiers is tantamount to a linear increase in the customer’s satis- faction.This model suggests four important points to the students wishing to market their product successfully. First, all basic needs must be fulfilled. Failure to satisfy a basic need has a dramatic

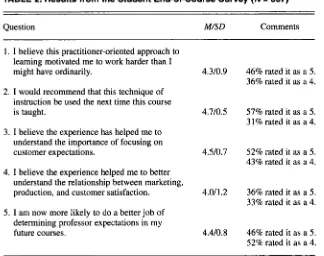

TABLE 2. Results from the Student End-of-Course Survey

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

( N = 357)zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Question

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

M/SD Comments1. I believe this practitioner-oriented approach to learning motivated me to work harder than I

might have ordinarily.

2.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I would recommend that this technique ofinstruction be used the next time this course

is taught.

3. I believe the experience has helped me to

understand the importance of focusing on

customer expectations.

4. I believe the experience helped me to better understand the relationship between marketing,

production, and customer satisfaction.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5. I am now more likely to do a better job of determining professor expectations in my future courses.

4.310.9

4.710.5

4.510.7

4.011.2

4.410.8

46% rated it as a 5.

36% rated it as a 4.

57% rated it as a 5.

3 1 %

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

rated it as a 4.52% rated it as a 5. 43% rated it as a 4.

36% rated it as a 5 . 33% rated it as a 4. 46% rated it as a 5. 52% rated it as a 4. Nore. Questions were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (dejhitely false), 2 (more false

than true), 3 (in between),

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

4 (more true than false), and 5 (definitely true).effect on customer satisfaction. In other

words, one

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

“ah

shucks” outweighs 10“atta boys.” Second, the provider must determine and provide as many linear satisfiers as possible. Each satisfier has an additive effect toward total customer satisfaction or customer loyalty. The customer will enter a zone of moderate satisfaction if the provider fulfills all of the customer’s basic needs and a few of the satisfiers. Third, the provider needs to create delighters, because real service differentiation is created through them. Each time a provider produces a delighter, it is a memorable event for the customer and his or her satisfaction is increased geometrically. Thus, one might say that one delighter outweighs a number of satisfiers. Fourth, any advan- tage gained by delighting customers only holds temporarily until the compe- tition catches up. Continuous innova- tion is necessary for maintaining an edge.

As we mentioned previously in the “product” section, we introduce our par- adigm as a market research task at the beginning of the semester. The class is assigned the task of determining and quantifying the professor’s needs

through brainstorming within groups and individual interviews with the pro- fessor. Often the use of Bloom’s taxono- my is an excellent tool for illustrating examples of basic needs, satisfiers, and delighters to the students.

Assessment: Learning and Enthusiasm

We conducted an assessment of the professor-as-customer approach over 4 semesters of a principles of marketing course at a public university and a pri- vate college. Two professors taught 12 sections of 357 students between fall 2000 and fall 2002. We used three types of evaluations to assess the students’ enthusiasm for this teaching technique and their understanding of the relation- ship between customer satisfaction, marketing, and production.

For the first method of assessment, we asked students questions taken from a nationally standardized student survey

(IDEA form) to investigate their percep-

tions of the instructors’ teaching and the students’ progress toward certain specif- ic learning objectives. We selected eight questions from the 47-item form; three

for instructor’s teaching and five for learning progress. In turn, each profes- sor calculated the students’ mean responses for each of the eight questions over the 2-year period before the test. We compared these means with the stu- dent means from the test period through a t test (see Table 1). Implicit in these comparisons were the notional hypothe- ses that the test period (T2) responses would be significantly higher than the pretest (Tl) responses at the p < .05 level of significance.

The results indicate that six out of the eight hypotheses were supported at a p < .05 level of significance. Particularly noteworthy were the high mean scores on the questions regarding students’ progress in relating course materials to real-life situations, their development of competencies needed by the profession, and instructor availability for student- faculty interaction. The test sample means for the learning objective con- cerning the development of competen- cies needed by the profession was rated in the top 2% of the nation for both fac- ulty members.

The second method of assessment was a four-question, end-of-course sur- vey that we administered to the test group of students to ascertain their atti- tudes toward the professor-as-customer paradigm. We strongly encouraged the students to clarify their responses by commenting in the space below each question so that we could capture their perceptions accurately (see Table 2).

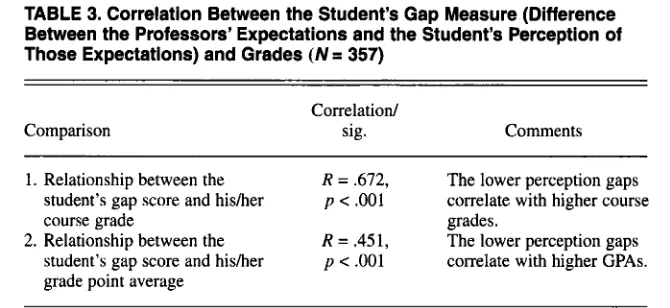

In the third method of assessment, we compared the professors’ expectations with the students’ perceptions of those expectations. At the beginning of each semester, the two participating profes- sors brainstormed to develop a compos- ite of their expectations for student pro- jectdterm papers in terms of the Kano categories (see Figure 2). On the end- of-course survey, the students were given a list of the professors’ 28 expec- tations and asked to indicate which ones were basic needs, satisfiers, and delighters. In turn, we developed an expectation gap measure by comparing the students’ perceptions of the profes- sors’ expectations with those indicated by the professors. We calculated a gap measure for individual students by giv- ing them a score of -3 for each missed

NovembedDecember 2002 101

[image:6.612.57.381.60.316.2]TABLE 3. Correlation Between the Student‘s Gap Measure (Difference Between the Professors’ Expectations and the Student’s Perception of

Those Expectations) and Grades ( N

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

=zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

357)zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I

Comparison

I

Correlation/

sig. Comments

I

1. Relationship between the

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

R = ,672,zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

p < .001

R = .451, p < .001

The lower perception gaps correlate with higher course

The lower perception gaps correlate with higher GPAs.

student’s gap score and hisher

course grade grades.

student’s gap score and hisher grade point average

2. Relationship between the

I Note. A high perception gap score indicates that the student was very perceptive in determining the professor’s expectation.

basic need, +1 for each identified satis- fier, and +2 for each identified delighter. In turn, we conducted correlation analy- ses to compare the gap measures with the students’ course grades and overall grade point averages. Implicit in these comparisons were the notional hypothe- ses that there would be significant and positive correlation between the stu- dent’s ability to properly perceive the professors’ expectations and his or her course grade. Furthermore, we believed that students who properly perceived the professor’s expectations probably would have a higher degree of “pattern sense,” which would be reflected in a higher grade point average (Butler,

1978) (see Table 3).

Conclusions

Overall, this experiment in experien- tial learning appeared to be an over- whelming success. Students demon- strated increased progress on the nationally normed learning objectives, increased motivation to work harder, and a keener understanding of the rela- tionship between customer expectations and customer satisfaction. In this case,

learning the skill of understanding pro- fessor expectations is particularly ger- mane to the real world. Today’s employ-

ers indicate that undergraduates do a poor job of understanding supervisor expectations (Emery, 2002).

The students who participated in this exercise realized that we are all trying to market our products, whether these are ideas or concepts. They began to under- stand the philosophy that customer satis- faction is a key and most worthwhile means to an end. Furthermore, use of the Kano model helped them develop a life strategy based on awareness of the need to fulfill a customer’s basic expectation and then concentrate on the delighters.

The question of whether this experi- ment actually provided the students with a better understanding of the link- ages among the four Ps (i.e., learning) seems clear. The students’ self-reported understanding of the information was very encouraging, and their answers to essay questions on the linkages among the four Ps were much more insightful and innovative than their answers on pre-experiment exams. However, the link between understanding the teacher’s expectations and learning is not so clear. Does increased learning of the subject matter take place through use of these teaching methods, or do the students simply learn how to better sat- isfy the customer? This is an area for future study.

We suggest that professors wishing to improve student understanding of the relationship between customer expectations and customer satisfaction try two activities. First, near the begin- ning of the semester they should assign a project in which the students identify and quantify the professor’s expecta- tions through use of the Kano model. Second, before following the profes- sor’s instruction on the four Ps, the professor could have the students pre- pare a short paper in which they apply the four Ps of marketing to the market- ing, production, and delivery of their schoolwork. We believe that instructors will find both of these exercises very enriching for their students.

REFERENCES

Butler, J. K. ( 1 978). Of rates and managers: Real-

ity testing the

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

LMX in the career maze. Unpub-lished manuscript. Clemson University, SC. Emery, C. R. (2001a). Student selfassessment: An

experiment in improving the value

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of studentproducts. Unpublished manuscript, 2001-3, Lander University, Greenwood, SC.

Emery, C. R. (2001b). The professor is the cus- tomer. In Lamb, Hair & McDaniel (Eds.), Great

ideas f o r teaching marketing (6th ed., pp. 86-89). New York: South-Western College Publishing.

Emery, C. R. (2003). Delighters, satisfiers and

basic needs: A study of supervisor expecta- tions. Manuscript in preparation.

Emery, C., Kramer, T., & Tian, R. (2001). Cus- tomers vs. products: Adopting an effective approach to the business students. Journal of

Quality Assurance in Education, 9(2), 34-4 1. Hill, T. (1989). Manufacturing strafegy. Home-

wood,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

IL: Irwin.DEA Form. (1998). Manhattan, KS: Kansas State University, Center for Faculty Evaluation and Development.

Kano, N., Seraku, N., Takahashi, F., & Tsuji. S. (1984). Attractive quality and must-be quality.

Hinshitsu, 14(2).39-48.

Oblinger, D. G., & Verville, A. (1998). What busi-

ness wants f m m higher education. Phoenix, AZ: The Oryx Press.

Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive strategy. New

York: Free Press.

Tian, R. G. (2001). Applying 4 Ps to students’

schoolwork. In Lamb, Hair, & McDaniel (Eds.), Great ideas for teaching marketing (6th ed., pp. 102-105). New York: South-Western College Publishing.

Zeithaml, V, A,, Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1988). Communication and control processes

in the delivery of service quality. Journal of

Marketing, 53, 36-39.

102