Heart Disease and Pregnancy

Cambridge University Press

978-1-107-09594-6 - Heart Disease and Pregnancy: Second Edition Edited by Philip J. Steer and Michael A. Gatzoulis

Frontmatter More information

Edited by Philip J. Steer and Michael A. Gatzoulis Frontmatter

More information

Heart Disease and Pregnancy

Second Edition Edited by

Philip J. Steer, BSc MD FRCOG

Emeritus Professor, Imperial College London, Academic Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London, UK

Michael A. Gatzoulis, MD PhD FACC FESC

Professor of Cardiology, Congenital Heart Disease and Consultant Cardiologist, Adult Congenital Heart Centre and Centre for Pulmonary Hypertension, Royal Brompton Hospital, and the National Heart & Lung Institute, Imperial College London, UK

Cambridge University Press

978-1-107-09594-6 - Heart Disease and Pregnancy: Second Edition Edited by Philip J. Steer and Michael A. Gatzoulis

Frontmatter More information

University Printing House, Cambridge CB2 8BS, United Kingdom

Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge.

It furthers the University’s mission by disseminating knowledge in the pursuit of education, learning and research at the highest international levels of excellence.

www.cambridge.org

Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9781107095946 © Cambridge University Press (2006) 2016

Th is publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press.

First published: 2006 by RCOG Press Second edition Year 2016

Printed in the United Kingdom by TJ International Ltd. Padstow Cornwall

A catalog record for this publication is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data

Names: Steer, Philip J., editor. | Gatzoulis, Michael A., editor.

Title: Heart disease and pregnancy / edited by Philip J. Steer, Philip J. Steer, BSc MD FRCOG, Emeritus Professor, Imperial College London, Academic Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London, UK, Michael A. Gatzoulis, MD PhD FACC FESC, Professor of Cardiology, Congenital Heart Disease and Consultant Cardiologist

Adult Congenital Heart Centre and Centre for Pulmonary Hypertension Royal Brompton Hospital, and the National Heart & Lung Institute, Imperial College, London, UK.

Description: Second edition. | Cambridge, United Kingdom : Cambridge University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifi ers: LCCN 2015041127 | ISBN 9781107095946 (hardback) Subjects: LCSH: Heart diseases in pregnancy.

Classifi cation: LCC RG580.H4 H42 2016 | DDC 618.3/61–dc23 LC record http://lccn.loc.gov/2015041127 ISBN 978-1-107-09594-6 Hardback

Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Every eff ort has been made in preparing this book to provide accurate and up-to-date information which is in accord with accepted standards and practice at the time of publication. Although case histories are drawn from actual cases, every eff ort has been made to disguise the identities of the individuals involved. Nevertheless, the authors, editors and publishers can make no warranties that the information contained herein is totally free from error, not least because clinical standards are constantly changing through research and regulation. Th e authors, editors and publishers therefore disclaim all liability for direct or consequential damages resulting from the use of material contained in this book. Readers are strongly advised to pay careful attention to information provided by the manufacturer of any drugs or equipment that they plan to use.

Edited by Philip J. Steer and Michael A. Gatzoulis Frontmatter

More information

v

Section 1 – Pregnancy Counseling and Contraception

1. Preconception counseling for women with cardiac disease 1

Sarah Vause, Sara Th orne, and Bernard Clarke 2. Contraception in women with heart disease 6

Mandish K. Dhanjal

Section 2 – Antenatal Care: General Considerations

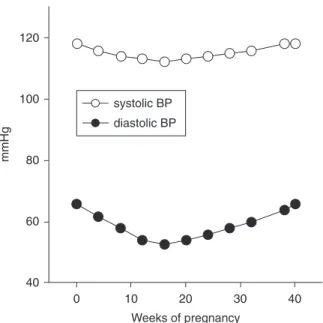

3. Cardiovascular changes in normal pregnancy 19

Mark Johnson and Katherine von Klemperer 4. Antenatal care of women with cardiac

disease: An obstetric perspective 29 Matthew Cauldwell, Martin Lupton, and Roshni R. Patel

5. Antenatal care of women with cardiac disease: A cardiac perspective 36 Fiona Walker

6. Cardiac monitoring during pregnancy 43 Henryk Kafk a, Sonya V. Babu-Narayan, and Wei Li

7. Cardiac drugs in pregnancy 53 Asma Khalil, Gerhard-Paul Diller, and Patrick O’Brien

8. Surgical and catheter intervention during pregnancy in women with heart disease 65 Henryk Kafk a, Hideki Uemura, and

Anselm Uebing

Section 3 – Antenatal Care: Fetal Considerations

9. Antenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease 84

Victoria Jowett and Julene S. Carvalho 10. Fetal care and surveillance in women with

congenital heart disease 96

Christina K. H. Yu and Tiong Ghee Teoh

Section 4 – Antenatal Care: Specifi c Maternal Conditions

11. Management of women with prosthetic heart valves during pregnancy 106

Carole A. Warnes

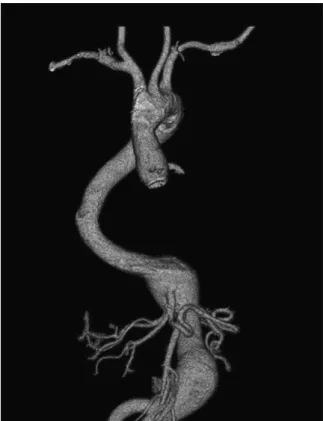

12. Management of aortopathies, including Marfan syndrome and coarctation, in pregnancy 115

Lorna Swan

13. Management of mitral and aortic stenosis in pregnancy 125

Sara Th orne

14. Management of right heart lesions in pregnancy 131

Annette Schophuus Jensen, Lars Søndergaard, and Anselm Uebing

15. Management of pulmonary hypertension in pregnancy 144

David G. Kiely, Charlie A. Elliot,

Victoria J. Wilson, Saurabh V. Gandhi, and Robin Condliff e

Contents

List of contributors vii Preface ix

Consensus statements x Cambridge University Press

978-1-107-09594-6 - Heart Disease and Pregnancy: Second Edition Edited by Philip J. Steer and Michael A. Gatzoulis

Frontmatter More information

vi

Contents

16. Management of cardiomyopathies in pregnancy 160

Catherine Nelson-Piercy and Catherine Head 17. Management of ischemic heart disease in

pregnancy 174

Jolien W. Roos-Hesselink and Iris M. van Hagen 18. Management of maternal cardiac arrhythmias

in pregnancy 180

Koichiro Niwa and Chizuko Kamiya 19. Management of maternal endocarditis in

pregnancy 191

Stephanie L. Curtis and Graham Stuart

20. Management of women with heart and lung transplantation in pregnancy 199

Coralie Blanche and Maurice Beghetti

Section 5 – Intrapartum Care

21. Pregnancy and cardiac disease: Peripartum aspects 208

David Alexander, Kate Langford, and Martin Dresner

Section 6 – Postpartum Care

22. Management of the puerperium in women with heart disease 218

Margaret Ramsay

23. Impact of pregnancy on long-term outcomes in women with heart disease 227

Henryk Kafk a and Natali A. Y. Chung

24. Long-term outcome of pregnancy with heart disease 234

Carole A. Warnes

Appendix A: New York Heart Association classifi cation of cardiovascular disease 240 Appendix B: Antenatal care pathway 241 Index 255

Th e colour plate section appears between pages 154 and 155.

Edited by Philip J. Steer and Michael A. Gatzoulis Frontmatter

More information

vii

David Alexander FRCA

Department of Anaesthetics, Royal Brompton Hospital, London, UK

Sonya V. Babu-Narayan BSc MRCP PhD Cardiovascular Biomedical Research Unit, Royal Brompton Hospital and Imperial College, London, UK

Maurice Beghetti MD

Pediatric Cardiology Unit, Children’s University Hospital, Geneva, Switzerland

Coralie Blanche MD

Adult Congenital Heart Disease Centre, Royal Brompton Hospital, London, UK

Julene S. Carvalho MD PhD FRCPCH

Royal Brompton Hospital and Fetal Medicine Unit, St George’s University Hospitals, St George’s University of London, London, UK

Matthew Cauldwell BSc MRCOG MRCP MEd Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Chelsea &

Westminster Hospital, London, UK

Natali A. Y. Chung MD FRCP

Department of Cardiology, Guy’s and St Th omas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Bernard Clarke BSc MD FRCP FESC FACC FRAeS FRCOG(Hon)

Department of Cardiology, Manchester Royal Infi rmary and Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

Robin Condliff e MD

Sheffi eld Pulmonary Vascular Disease Unit, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffi eld, UK

Stephanie L. Curtis BSc (Hons) MD FRCP Bristol Heart Institute, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust, Bristol, UK

Mandish K. Dhanjal BSc MRCP FRCOG

Queen Charlotte’s and Chelsea Hospital, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK

Gerhard-Paul Diller MD PhD MSc

Division of Adult Congenital & Valvular Heart Disease, University Hospital Münster, Münster, Germany

Martin Dresner FRCA

Department of Anaesthetics, Leeds Royal Infi rmary, Leeds, UK

Charlie A. Elliot FRCP

Sheffi eld Pulmonary Vascular Disease Unit, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffi eld, UK

Saurabh V. Gandhi MD MRCOG

Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffi eld, UK

Catherine Head MS PhD FRCP

Department of Cardiology, Guy’s and St Th omas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Annette Schophuus Jensen

Department of Cardiology, Copenhagen University Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark

Mark Johnson MRCP PhD MRCOG

Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Chelsea &

Westminster Hospital, London, UK

Victoria Jowett MRCPCH

Royal Brompton Hospital and Centre of Fetal Care, Queen Charlotte’s & Chelsea Hospital, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK

Henryk Kafka MD FRCPC FACC

Division of Cardiology, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada

Chizuko Kamiya MD

Department of Perinatology, National Cardiovascular Center, Osaka, Japan

List of contributors

Cambridge University Press

978-1-107-09594-6 - Heart Disease and Pregnancy: Second Edition Edited by Philip J. Steer and Michael A. Gatzoulis

Frontmatter More information

viii

List of contributors

Asma Khalil MD MRCOG MSc

St George’s Medical School, University of London, London, UK.

David G. Kiely MD FCCP

Sheffi eld Pulmonary Vascular Disease Unit, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffi eld, UK

Kate Langford MA MD MBA FRCOG

Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Guy’s and St Th omas’ Hospitals NHS Trust, London, UK

Wei Li MBBS MD PhD FESC FACC

Department of Echocardiography, Royal Brompton Hospital, London, UK

Martin Lupton MA MRCOG

Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Chelsea &

Westminster Hospital, London, UK

Catherine Nelson-Piercy MA FRCP FRCOG Women’s Health Academic Centre, St Th omas’

Hospital, London, UK

Koichiro Niwa MD PhD FACC FAHA FJCC Cardiovascular Center, St Luke’s International Hospital, Tokyo, Japan

Patrick O’Brien FRCOG FFSRH FICOG

Institute for Women’s Health, University College London Hospitals, London, UK

Roshni R. Patel MSc MRCOG

Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Chelsea &

Westminster Hospital, London, UK

Margaret Ramsay MA MD MRCP FRCOG Department of Obstetrics and Fetomaternal

Medicine, Nottingham University Hospitals, Queen’s Medical Centre Campus, Nottingham, UK

Jolien W. Roos-Hesselink MD PhD

Department of Cardiology, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Lars Søndergaard MD

Department of Cardiology, Copenhagen University Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark

Graham Stuart FRCP FRCPCH

Bristol Heart Institute, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust, Bristol, UK

Lorna Swan FRCP MD

Adult Congenital Heart Disease Unit, Royal Brompton Hospital, London, UK

Tiong Ghee Teoh MD FRCOG

Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, St Mary’s Hospital, London, UK

Sara Thorne MD FRCP

Department of Cardiology, University Hospital Birmingham, Birmingham, UK

Anselm Uebing MD PhD

Adult Congenital Heart Disease Centre, Royal Brompton Hospital, London, UK

Hideki Uemura MD MPhil FRCS

Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Royal Brompton Hospital, London, UK; Congenital Heart Disease Center, Nara Medical University, Nara, Japan

Iris M. van Hagen MD

Department of Cardiology, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Sarah Vause MD FRCOG

St Mary’s Hospital, Manchester, UK

Katherine von Klemperer MRCP Royal Brompton Hospital, London, UK

Fiona Walker FRCP FESC

Lead for Pregnancy & Heart Disease Program, UCLH and Barts Health NHS Trust, London, UK

Carole A. Warnes MD FRCP

Adult Congenital Heart Disease Clinic, Division of Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

Victoria J. Wilson FRCA

Department of Anaesthesia & Critical Care, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffi eld, UK

Christina K. H. Yu BSc MD MRCOG

Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, St Mary’s Hospital, London, UK

Edited by Philip J. Steer and Michael A. Gatzoulis Frontmatter

More information

ix

Since the turn of the twenty-fi rst century, cardiac dis- ease has become the leading medical cause of death in relation to pregnancy in the United Kingdom. In response to this, the meetings committee of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in London put together an international study group of 28 obste- tricians, cardiologists, anesthetists and other experts in related fi elds to discuss this challenge to maternal health. Th e group met on February 13–15, 2006 at the RCOG in London, and out of this meeting came the fi rst edition of Heart Disease and Pregnancy , published in the same year. Both the fi rst and second printing sold out, so clearly the book was meeting a need.

From 2010 onwards, there were increasing requests for an update to a volume that so many people had found useful. Unfortunately, the RCOG no longer funds such activities; study groups now concentrate on developing research proposals, and the publishing department has been closed, and its booklist transferred to Cambridge University Press. Fortunately, we were able to persuade Cambridge University Press of the need for a second edition, and we are grateful to Nick Dunton for tak- ing our proposals forward to success. In addition, one of us (MAG) runs a regular international meeting on congenital heart disease, and he was able to arrange a consensus session at one of the meetings (held at the Royal College of Surgeons in September 2014) where many of the original participants (and some new ones) gathered together to update the consensus statements . Consensus statements are necessary because there is a paucity of randomized trials in relation to heart dis- ease in pregnancy, and therefore clinical guidelines rely heavily upon expert opinion. Funding for randomized trials or international collaborative studies is diffi cult to obtain because globally, maternal and child health have a low political priority. In addition, the increas- ing number of international regulations applying to

any studies involving drug therapy make randomized trials extremely expensive, especially when the condi- tions studied are individually relatively uncommon.

However, the growing number of surviving women with corrected or ameliorated congenital heart dis- ease, and the increasing attempts to improve maternal health globally, means that guidelines are required for the growing number of centers dealing with pregnant women with heart disease.

We are grateful to those authors who have updated their previous chapters, and there have been a consid- erable number of new contributors, who have looked at things afresh, and sometimes contributed entirely new chapters (for example, on transplantation). Th e chap- ters are laid out in a way that we hope readers will fi nd intuitive, starting with prepregnancy counseling and contraception, moving through the antenatal period to delivery and the puerperium, and fi nishing with long-term outcome. Th ere is some overlap between chapters, for example the physiological changes of pregnancy are oft en recapped at the beginning. Th e purpose of this is to make each chapter comprehensi- ble in its own right, both for easy initial reading, and for rapid revision. We have done our best to make sure that there is no signifi cant confl ict between the content of the various chapters.

In the fi rst edition, we had a special section at the end for the consensus statements, both “overarching”

and specifi c to individual chapters. In response to feedback from the many readers who felt the consen- sus statements were particularly useful, we have now put the overarching statements right at the front of the book, and those that are more specifi cally condition related are included at the beginning of their appropri- ate chapters as “practical practice points.” We hope that this innovation will make the book even more useful than the fi rst edition.

Preface

Cambridge University Press

978-1-107-09594-6 - Heart Disease and Pregnancy: Second Edition Edited by Philip J. Steer and Michael A. Gatzoulis

Frontmatter More information

x

Th e following consensus statements were draft ed at a face to face meeting at the Royal College of Surgeons (London) on September 30, 2014, and subsequently agreed by email. Th ey are followed by the list of partici- pants in the meeting, and a photograph of them on the steps of the Royal College of Surgeons.

Defi nitions

1. Multidisciplinary Team (MDT). Th e core members of the MDT should be appropriately trained obstetricians, cardiologists, and anesthetists, and the wider team who should also be involved in care when appropriate may include midwives, neonatologists, intensivists, obstetric physicians, hematologists, specialist nurses and geneticists.

2. A tertiary unit is defi ned as a hospital (or group of hospitals) able to provide combined obstetric, cardiological, anesthetic and cardiac surgical expertise in the care of women with heart disease.

Any tertiary center caring for pregnant women with heart disease should have facilities for prolonged high-level maternal surveillance with direct access to adult critical care facilities.

Overarching consensus views General

1. Th ere should be national and international registries for the collection of data on pregnancy in women with heart disease. Th ese data should be collected centrally to enable a more detailed analysis of risk factors for poor pregnancy and long-term outcomes (including maternal survival and infant disability). Such information would greatly improve the counseling of women with heart disease.

2. Th ere should be recognized networks for the provision of care for women with both acquired and congenital heart disease and appropriate referral links should be established. Th ese will need to be specifi cally funded as the care of these women cannot be provided from routine obstetric and cardiac resources.

3. If any pregnant or postpartum woman has unexpected and persistent cardiorespiratory symptoms she should have thorough evaluation of possible cardiovascular causes such as

cardiomyopathy, acute coronary syndrome, aortic dissection and pulmonary embolism.

Preconception

1. A proactive approach to preconception counseling should be started in adolescence (at age

12–15 years, depending on individual maturity) and should include advice on safe and eff ective contraception. Comprehensive advice should be given at the appropriate age and not delayed until transfer to the adult cardiological services.

2. All women of reproductive age with congenital or acquired heart disease should have access to specialized multidisciplinary preconception counseling with regular reevaluation to enable them to make a fully informed choice about pregnancy.

3. When assisted conception is being planned, the advice of the MDT should be sought before any such treatment is commenced.

4. In counseling women about motherhood,

alternatives to the woman carrying the baby herself can be considered (for example surrogacy or adoption).

5. Women with a family history of inherited cardiac conditions should be screened before pregnancy.

Consensus statements

Edited by Philip J. Steer and Michael A. Gatzoulis Frontmatter

More information

Consensus statements

xi

6. Any cardiac surgical interventions in women of childbearing age should take into account the eff ect they may have on pregnancy. For example, because of the risks associated with prosthetic mechanical valves in pregnancy, consideration should be given to valve repair or using tissue valves for valve replacement.

7. Contraceptive choice for women with heart disease should be tailored to the particular patient, taking into account any increased risks of thrombosis or infection associated with the various contraceptive methods and their interaction with the various heart lesions or drugs being taken.

Antenatal care

1. Once women with heart disease are pregnant, they should be referred to the MDT as soon as possible. Th e timing and frequency of follow-up visits should be determined by the MDT. Direct self-referral should also be allowed, to avoid delays.

2. Medication should be reviewed and adjusted as necessary.

3. Th e threshold for starting thromboprophylaxis should be determined by the MDT.

4. Th rombolysis may cause bleeding from the placental site but should be given in women with life-threatening thrombotic disease.

5. Following assessment by the MDT, care can be arranged at a local hospital or tertiary unit (where the MDT is based), according to the complexity of the heart disease, the risk assessment and the locally available facilities and expertise. Shared care between the local and tertiary hospitals may be appropriate, in which case a detailed plan of care should be documented and accessible to all care providers.

6. A copy of the plan should be carried by the woman herself, so it is available in an emergency to care providers other than her usual team.

7. Women with congenital heart disease should be off ered fetal echocardiography.

8. Tertiary units should off er a hotel facility to enable women who live some distance from the hospital to stay on site, to avoid (a) a delay in receiving appropriate care when they go into labor and (b) the need to induce labor solely to avoid this risk.

Intrapartum care

1. Management of intrapartum care should be supervised by a team experienced in the care of women with heart disease (obstetrician, anesthetist and midwife), with a cardiologist or appropriately experienced obstetric physician readily available.

2. A clear plan for management of delivery and the puerperium in women with heart disease should be established in advance, be well documented and be distributed widely (including to the woman herself) so that all personnel likely to be involved in the woman’s intrapartum and postpartum care are fully informed. It is recommended that the woman should carry her own notes (or at least a copy of them) at all times. Th ere should be clear arrangements for contacting the MDT in case of an emergency.

3. Vaginal delivery is the preferred mode of delivery over cesarean section for most women with heart disease—whether congenital or acquired—unless obstetric or specifi c cardiac considerations determine otherwise. Th is can be facilitated where appropriate by the use of regional anesthesia and assisted vaginal delivery.

4. Induction of labor may be appropriate, to optimize the timing of delivery in relation to anticoagulation and the availability of specifi c medical staff or because of deteriorating maternal cardiac function.

5. In the management of the third stage of labor in women with heart disease, low-dose oxytocin infusions are safer than bolus doses of oxytocin, which can cause hypotension. Ergometrine is best avoided if systemic hypertension is a concern.

Misoprostol is an eff ective uterotonic although it can cause problems such as hyperthermia.

6. When planning care, specifi c instructions should be recorded regarding intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis. Th ere is no evidence that prophylactic antibiotics prevent endocarditis in an uncomplicated vaginal delivery. However, prophylactic antibiotic cover should be given to women undergoing an operative delivery, and to women at increased risk of infectious endocarditis, such as those with mechanical valves or a history of previous endocarditis and to women before any intervention that is likely to be associated with signifi cant or recurrent bacteremia. Th e possibility of endocarditis should always be borne in mind.

Cambridge University Press

978-1-107-09594-6 - Heart Disease and Pregnancy: Second Edition Edited by Philip J. Steer and Michael A. Gatzoulis

Frontmatter More information

xii

Consensus statements

List of participants in the consensus meeting

Adamson Dawn Cardiologist Coventry

Chung Natali Cardiologist Guy’s and St Thomas’

Clarke Bernard Cardiologist Manchester

Curtis Stephanie Cardiologist Bristol

Dhanjal Mandish Obstetrician Queen Charlotte’s Hospital

Gatzoulis Michael Cardiologist Imperial College London

Head Cathy Cardiologist Guy’s and St Thomas’

Jensen Annette Cardiologist Copenhagen, Denmark

Johnson Mark Obstetrician Imperial College London

Kamiya Chizuko Cardiologist Osaka, Japan

Li Wei Cardiologist Royal Brompton Hospital

Nelson-Piercy Catherine Obstetric Physician Guy’s and St Thomas’

Patel Roshni Obstetrician Chelsea and Westminster Hospital

Ramsay Margaret Obstetrician Nottingham

Roos-Hesslink Jolien Cardiologist Rotterdam, Netherlands

Søndergaard Lars Cardiologist Copenhagen, Denmark

Steer Philip Obstetrician Imperial College London

Van Hagen Iris Cardiologist Rotterdam, Netherlands

Vause Sarah Obstetrician Manchester

Von Klemperer Kate Cardiologist Royal Brompton Hospital

Warnes Carole Cardiologist Mayo Clinic, USA

Yu Chrissie Obstetrician St Mary’s Hospital, London

Postpartum care

1. High-level maternal surveillance is required until the main hemodynamic challenges

following delivery have passed. Multidisciplinary

surveillance should be maintained until it is judged the woman is well enough to leave hospital.

Follow-up assessment should be arranged by the MDT. Contraceptive advice must be given.

Edited by Philip J. Steer and Michael A. Gatzoulis Frontmatter

More information

Consensus statements

xiii

Figure X.1. Front row, left to right

Michael Gatzoulis, Philip Steer, Mandish Dhanjal, Bernard Clarke, Margaret Ramsay, Natali Chung, Sarah Vause, Jolien Roos-Hesslink, Cathy Nelson-Piercy, Stephanie Curtis

Behind, from left

Mark Johnson, Roshni Patel, Iris van Hagen, Kate von Klemperer, Chrissie Yu, Dawn Adamson, (partially obscured, Annette Jensen), Carole Warnes, Lars Søndergaard, Kamiya Chizuko, Cathy Head, Wei Li

Picture of the participants in the consensus meeting

Cambridge University Press

978-1-107-09594-6 - Heart Disease and Pregnancy: Second Edition Edited by Philip J. Steer and Michael A. Gatzoulis

Frontmatter More information

Heart Disease and Pregnancy, 2nd edn. ed. Philip J. Steer and Michael A. Gatzoulis. Published by Cambridge University Press.

© Cambridge University Press 2016.

Chapter

Practical practice points

1. All women of reproductive age with congenital or acquired heart disease should have access to specialized multidisciplinary preconception counseling with regular reevaluation so as to empower them to make choices about pregnancy.

2. Preconception counseling should include assessment and optimization of the woman’s cardiac condition to minimize the risk of pregnancy.

3. Preconception counseling should include a discussion of contraceptive choices, and should be tailored to the woman’s individual medical and social circumstances .

Introduction

Th e majority of women want to have children, and women with heart disease are no exception. Complex heart disease is no bar to sexual activity. Most women with heart disease do have some awareness of the risks of pregnancy but their ideas are oft en inaccurate, rang- ing from overly optimistic to overly pessimistic.[ 1 ] Th ey may be equally poorly informed about the prog- nosis of their heart condition, even in the absence of pregnancy. Many doctors do not have a good under- standing of the risks of pregnancy in women with heart disease and thus such women may be deprived of appropriate advice and counseling unless a special- ist referral is made. In the 2011 UK maternal mortal- ity report, there was some degree of substandard care in 51% of deaths from cardiac causes: lack of precon- ception care was one aspect identifi ed as substandard . [ 2 ] Better provision of preconception care was one of the “top ten recommendations” from this report.[ 2 ] Discussions with a cardiologist and/or an obstetric

physician with a specialist interest in pregnancy and heart disease should begin in adolescence. Th ese dis- cussions should cover future pregnancies and their prevention, both to prevent accidental and possi- bly dangerous pregnancies and to allow patients to come to terms with their future childbearing poten- tial. Th ey also need to be able to plan their families in the knowledge of their likely future health and life expectancy.

In the UK, the majority of women seen precon- ception by cardiologists and/or obstetricians will be women with congenital heart disease (CHD). Th is is because the incidence of CHD (0.8%) in preg- nant women in the UK is higher than the incidence of acquired heart disease (0.1%). Furthermore, most women with CHD are already known to cardiac ser- vices, while women with acquired heart disease may be unaware of their condition, or the condition itself may only present during pregnancy or in the postnatal period .

Components of preconception counseling

Preconception counseling should ideally [ 3 ]:

• display attitudes and practices that value pregnant women, children and families and respect the diversity of people’s lives and experiences

• incorporate informed choice, thus encouraging women and men to understand health issues that may aff ect conception and pregnancy

• encourage women and men to prepare actively for pregnancy, and enable them to be as healthy as possible

• attempt to identify couples who are at increased risk of having babies with a congenital

Preconception counseling for women with cardiac disease

Sarah Vause , Sara Th orne , and Bernard Clarke

1

Section 1: Pregnancy Counseling and Contraception

abnormality and provide them with suffi cient knowledge to make informed decisions.

Th ese four components will be discussed below in relation to cardiac disease in pregnancy .

Valuing the cultural background of the woman and her family, and respecting diversity

Preconception counseling should display attitudes and practices that value pregnant women, children and families and respect the diversity of people’s lives and experiences. All women have a cultural context within a multicultural society. For some women, issues related to culture may need specifi c attention, including:

• their religious beliefs (particularly in relation to contraception and termination of pregnancy)

• the role of the partner and extended family in pregnancy decisions

• communication, where English is not the fi rst language.

Assumptions are oft en made about the anticipated views of certain racial, cultural, or religious groups and this may consciously or subconsciously aff ect the way in which doctors counsel women. Addressing these overtly helps one to compensate for any unintentional bias.

All people have a social and emotional context, and when women and their partners seek advice this context must be considered. Th eir attitudes and expec- tations are likely to have been infl uenced by their previous experiences and those of their family. Th ese may include the anxieties of overprotective parents or worries relating to their inability to embark on, or continue, a meaningful relationship if pregnancy is contraindicated.

While it is important to explore and respect the context of a woman’s cultural background, preconcep- tion counseling should promote the autonomy of the woman. It should enable her to determine her own per- sonal priorities and support her decision-making .

Informed choice and understanding

Preconception counseling should provide information in a frank, honest and understandable way so as to give the woman a realistic estimate of both maternal and fetal risk and allow her to make an informed decision as to whether to embark on a pregnancy or not. Th e counseling should include information on:

• the eff ects of cardiac disease on pregnancy, in terms of both maternal and fetal risks

• the eff ects of pregnancy on cardiac disease, including the risk of dying or long-term deterioration

• whether these eff ects will change with time or treatment

• the other options that may be available, such as contraception, surrogacy or adoption

• the long-term outlook—a woman with a short life expectancy may feel that pregnancy, surrogacy, or adoption is not appropriate, as a child may then have to deal with the terminal illness and death of the mother .

Th e diffi culty for the cardiologist and obstetrician is to provide an accurate assessment of risk. For some com- plex conditions, there is little or no information avail- able, either because of the rarity of the woman’s disease or because they represent a new cohort of survivors to adulthood with a surgically modifi ed disease.

Scoring systems, such as CARPREG (“CARdiac dis- ease in PREGnancy”) and ZAHARA (“Zwangerschap bij Aangeboren HARtAfwijkingen I”), have been devised to predict the chance of maternal cardiac or neonatal complications during pregnancy.[ 4 , 5 ] However, such scoring systems do not predict complications that are specifi c to certain conditions, e.g. aortic dissection in Marfan syndrome. Perhaps the most important message to take from these scoring systems is which risk factors can be useful in predicting poor outcome. Th e European Society for Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on cardiovas- cular diseases in pregnancy provide an overall classifi ca- tion of the risk of maternal mortality and morbidity .[ 6 ] For specifi c conditions, data can be obtained from the literature. However, studies are frequently small, retrospective and derived from women managed in a single center. A literature review of papers relating to pregnancy outcomes in women with structural CHD was published by Drenthen et al. , and informed the ESC guidelines.[ 6 , 7 ]

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing has been studied to determine whether the increase in cardiac output during exercise would act as a surrogate for that seen in pregnancy and, therefore, whether it could be used to predict pregnancy outcome. Impaired maximal oxy- gen uptake and chronotropic response (failure to raise heart rate adequately) during exercise correlate with poor pregnancy outcome,[ 8 ] and, therefore, may be included in the preconception assessment.

A woman should be informed that the main risks to her include:

• maternal death— the highest risk is in women with pulmonary arterial hypertension; those with poor systemic ventricular function, severe left -sided obstruction and severe aortopathy are also at high risk

• arrhythmias (particularly in women with Fontan circulation or atrial repair of transposition of the great arteries), heart failure (particularly in women with pre-existing ventricular impairment with or without coexistent valve disease, ischemic heart disease, cyanotic CHD, a systemic right ventricle or a Fontan circulation), including progression of ventricular dysfunction and permanent deterioration following pregnancy

• acute coronary syndrome in women with known pre-existing coronary disease

• aortic dissection in women with inherited

aortopathies (particularly Marfan and Loeys-Dietz syndromes, but also with bicuspid aortopathy)

• thromboembolism (particularly in women with cyanotic CHD, prosthetic valves or a Fontan circulation)

• the potential need for earlier intervention for valve disease as a result of pregnancy .

Th e risks to the fetus include the following:

• fetal growth restriction, particularly in women taking beta-blockers or with cyanotic heart disease or a Fontan circulation

• iatrogenic or spontaneous preterm delivery, which may result in long-term disability in the child

• recurrence of CHD (typical risk of 3–5%, but this varies with the type of maternal lesion, and is also related to paternal lesions) or a genetically inherited cardiac condition

• teratogenesis or fetotoxicity from drugs, for example from warfarin or angiotensin-converting- enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

• fetal loss resulting from invasive prenatal testing . One successful pregnancy should not engender com- placency. Some conditions, such as peripartum cardiomyopathy, have a high recurrence risk and preconception counseling before embarking on a subsequent pregnancy is recommended.[ 2 , 9 ] Other conditions can worsen with age and the risks will be higher in each subsequent pregnancy .

Information about contraception and termination Facilitating informed choice also means that doctors must provide information relating to the choice of not

being pregnant. Th is includes advice about appropri- ate contraception and information about termination of pregnancy services. Th e assurance that clinicians will be nonjudgmental and supportive of a decision to terminate a pregnancy is important. Open discussion of these options and provision of contact numbers to facilitate access to these services reinforces that these are options available to the woman.[ 10 ] Termination of pregnancy in women with heart disease is not with- out risks, and it should be performed in a center with appropriate anesthetic and cardiac facilities. Specialist advice on contraception may need to be obtained from specialist sexual health services .

Information about clinical management

During the preconception appointment the proposed plan of care for the pregnancy should be outlined.

Women with signifi cant cardiac disease should be managed in a center with appropriate expertise, prefer- ably in a joint obstetric–cardiac clinic, even though for some women this may mean traveling long distances.

Women should be made aware of how likely, or not, it would be that they would need admission antenatally, iatrogenic preterm delivery, lower segment cesarean section (LSCS) or high dependency care in a hospital that may be many miles from home .

Information in an appropriate language

If the woman and her doctor do not speak the same lan- guage, a professional interpreter should be employed.

Interpreters from within the family, including the hus- band, should be avoided as in the family’s desire to help the woman have a successful pregnancy the risks may not be accurately relayed to her. Th is has been a recom- mendation from three UK maternal mortality reports . [ 2 ,10, 11 ]

Preparing for pregnancy

Th e preconception consultation provides the ideal opportunity to minimize risks and optimize cardiac function before pregnancy [ 12 ]:

• valvotomy, valve repair or replacement before pregnancy—if valve replacement is performed, the choice of the type of valve used may be infl uenced by the desire for future pregnancy. Risks should be balanced between the use of tissue valves, obviating the need for anticoagulation during pregnancy but carrying the risk of inevitable reoperation, and the use of mechanical valves,

Section 1: Pregnancy Counseling and Contraception

mandating the use of anticoagulation during pregnancy, but (potentially) obviating the need for future surgery

• treatment of arrhythmias (interventional or medical)

• treatment of underlying medical conditions, such as hypertension or diabetes

• avoidance of teratogens—medication may need to be changed before pregnancy

• discussion about anticoagulation—women using warfarin need to be aware of its teratogenic potential and the risk of fetal intracranial hemorrhage, and should understand the advisability in most cases for conversion to heparin once pregnancy is confi rmed. Contact numbers should be provided to facilitate this as early as possible in pregnancy. For women with mechanical valves, the risks of warfarin vs the risks of low-molecular-weight heparin should be discussed to enable them to make an informed choice about which anticoagulant regime should be used during pregnancy

• dental treatment—women with complex heart disease may need to be referred to a tertiary dental hospital for dental care. It is preferable for any dental problems to be addressed and resolved before pregnancy

• timing of pregnancy—for those with progressive disease (e.g. a systemic right ventricle or univentricular heart), pregnancy is likely to be tolerated better when the woman is younger.

Such women should be discouraged from purposely delaying pregnancy because of other considerations such as a career

• contraception—until the above cardiac problems have been appropriately addressed, the provision of appropriate contraception is paramount

• general prepregnancy advice should not be forgotten, for example taking folic acid to reduce the risk of neural tube defect in the baby, smoking cessation, weight management etc.

• provision of phone numbers to facilitate prompt contact and reassessment once pregnancy is confi rmed.

Women undergoing assisted conception oft en have additional risk factors such as increased age and the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation and multiple preg- nancy, with a concomitant increase in the risk of

preeclampsia. Th ese conditions can compound the risk of heart disease, and ovarian hyperstimulation may be fatal in women with impaired ventricular function or a Fontan circulation. In women undergoing assisted conception, it is important that precautions should be taken to avoid hyperstimulated cycles and to mini- mize the chance of multiple pregnancy by carrying out single-embryo replacements during in vitro fertiliza- tion (IVF) cycles .

Risk of congenital abnormality

Many couples have worries about the risk of CHD in their unborn baby. For the majority of women with CHD (with no family history and no chromosomal abnormality), the risk of recurrence of CHD in the fetus is around 3–5%. Prenatal fetal echocardiography should be arranged and couples can be reassured that the most likely outcome is a healthy baby.

For women known to have, or suspected of having, a genetically inherited cardiac condition, the precon- ception appointment off ers the opportunity to refer a woman to a clinical geneticist. Tetralogy of Fallot, when associated with underlying genetic disorders such as 22q11.2 deletion (DiGeorge syndrome), car- ries a much higher recurrence risk than when tetralogy of Fallot occurs in the absence of an underlying genetic syndrome.

It can be diffi cult for most clinicians to recognize rare genetic syndromes, so doctors should have a low threshold to make a genetics referral, especially if there is a family history of CHD. Although a woman may have previously been seen by a geneticist, she may welcome the opportunity to discuss the risks to the fetus again once she begins to contemplate pregnancy.

Preconception care should also include a discussion of the various prenatal tests available for the detection of fetal abnormality, their risks and limitations, the timing of the tests, and the way in which they are performed.

Information about how to access these tests, includ- ing contact numbers, should be provided. Discussion should include the options available, including termi- nation, if the fetus is found to be abnormal. Women should be encouraged to carefully consider the implica- tions of testing, and whether they would terminate the pregnancy if the baby is found to be abnormal, prior to embarking on testing (the choice may vary according to the nature of the fetal abnormality) .

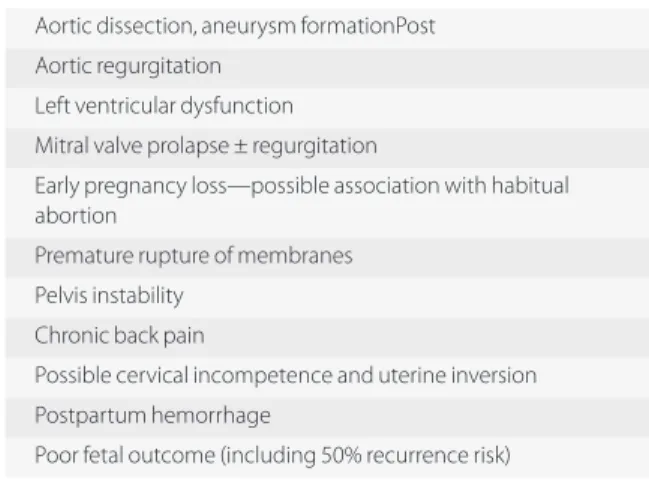

For women with conditions such as Marfan syn- drome, the preconception appointment off ers the opportunity to discuss the risk that their baby will be aff ected (which is 50% as it is a single dominant gene abnormality, assuming the father is unaff ected) and whether they would like early screening, for exam- ple preimplantation diagnosis (which requires IVF), or no screening at all. If a decision for no screening is made, the infant needs to be followed up postna- tally to establish a diagnosis. If Marfan syndrome is diagnosed, long-term surveillance needs to be implemented .

Conclusion

Successful preconception counseling will empower a woman with cardiac disease to make informed choices relating to pregnancy by providing nondirective coun- seling and access to the appropriate multidisciplinary specialized services. Optimizing her health before pregnancy will improve the likelihood of a successful pregnancy outcome .

References

1. Moons P , De Volder E , Budts W , et al. What do adult patients with congenital heart disease know about their disease, treatment and prevention of complications?

A call for structured patient education . Heart 2001 ; 86 : 74 – 80 .

2. Cantwell R , Clutton-Brock T , Cooper G . Saving Mothers’ Lives: Reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006–2008. Th e Eighth Report of the Confi dential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom . BJOG 2011 ; 118 ( Suppl. 1 ): 1 – 203 . 3. Health Canada . Family-Centred Maternity and Newborn

Care: National Guidelines . Ottawa : Ministry of Public Works and Government Services ; 2000 [ www.hc-sc.

gc.ca ]

4. Siu SC , Sermer M , Colman JM , et al. Prospective Multicenter Study of Pregnancy Outcomes in Women With Heart Disease Circulation 2001 ; 104 ; 515–21 . 5. Drenthen W , Boersma E , Balci A , et al. Predictors of

pregnancy complications in women with congenital heart disease . Eur Heart J 2010 ; 31 : 2124–32 . 6. European Society of Gynecology (ESG) , Association

for European Paediatric Cardiology (AEPC) , German Society for Gender Medicine (DGesGM) , et al. ESC Guidelines on the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy: Th e Task Force on the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases during Pregnancy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) . Eur Heart J 2011 ; 32 : 3147–97 .

7. Drenthen W , Pieper PG , Roos-Hesselink JW , et al. on behalf of the ZAHARA Investigators.

Outcome of pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease: A literature review . JACC 2007 ; 49 ( 24 ): 2303–11 .

8. Lui GK , Silversides CK , Khairy P , et al. Alliance for Adult Research in Congenital Cardiology (AARCC) . Heart rate response during exercise and pregnancy outcome in women with congenital heart disease . Circulation 2011 ; 123 : 242–8 .

9. Elkayam U , Tummala PP , Rao K , et al. Maternal and fetal outcomes of subsequent pregnancies in women with peripartum cardiomyopathy . N Engl J Med 2001 ; 344 : 1567–71 .

10. Drife JO , Lewis G , Clutton-Brock T , eds. Why Mothers Die: Th e Sixth Report of the Confi dential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom 2000–2002 . London : RCOG Press ; 2004 .

11. Lewis G , ed. Saving Mothers’ Lives: Reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer 2003–

2005. Th e Seventh Report on Confi dential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom . London : CEMACH 2007 .

12. Th orne SA . Pregnancy in heart disease . Heart 2004 ; 90 : 450–6 .

Heart Disease and Pregnancy, 2nd edn. ed. Philip J. Steer and Michael A. Gatzoulis. Published by Cambridge University Press.

© Cambridge University Press 2016.

Chapter

Pregnancy Counseling and Contraception

Section 1

Practical practice points

1. A key requirement for contraception in women with severe heart disease is maximum effi cacy because the consequences of contraceptive failure can be fatal.

2. Subdermal progestogen implants (such as

Nexplanon ® ) and progestogen-loaded intrauterine devices (such as Mirena ® ) are the most effi cacious forms of contraception and are also safe methods for most women with signifi cant heart disease.

3. In the event of unprotected sexual intercourse, women with heart disease should be aware that emergency contraception, known to be safe for women with heart disease, is available.

4. Urgent access to termination of pregnancy should be readily available within a hospital equipped to deal with the woman’s cardiac condition .

Introduction

Cardiac disease is the main cause of maternal mortal- ity in the UK, being responsible for 20% of maternal deaths.[ 1 ] Th e major pathologies causing mortality are cardiomyopathy (mainly peripartum cardiomyopa- thy), ischemic heart disease, sudden adult death syn- drome, and dissection of the thoracic aorta.

Th ere are a handful of cardiac conditions in which pregnancy is not advisable because of mortality rates approaching 25%. It is imperative that women with these conditions have the most reliable methods of contraception available. However, contraceptive agents may themselves infl uence heart disease or may inter- act with medications used by such women. Th e World Health Organization (WHO) has classifi ed contracep- tive agents into four classes depending on their suit- ability for use in medical conditions (WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria [WHOMEC]).[ 2 ] Th is classifi cation

has been incorporated into the subsequently devel- oped UK Medical Eligibility Criteria (UKMEC) shown in Table 2.1 .[ 3 ]

Th e UKMEC classifi cation for an individual agent will vary according to circumstance and concomitant medical illnesses such as cardiac disease, hypertension, and diabetes. For example, a woman starting the com- bined oral contraceptive (COC) pill will be classifi ed as:

• UKMEC 1 if she is aged under 40 years

• UKMEC 2 if she is aged 40 years or older

• UKMEC 3 if she has adequately controlled hypertension

• UKMEC 4 if she is hypertensive with systolic blood pressure ≥160 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥95 mmHg .

Counseling patients on the risks of pregnancy

Adolescents with congenital heart disease (CHD) should have the issue of pregnancy and contraception discussed with them at age 12–15 years (depending on the individu- al’s maturity). Th is will usually take place in the pediatric cardiology clinic. Transition from pediatric to adult ser- vices should include information about the individual’s cardiac disease, her risks from pregnancy, and her risks from contraceptive use, specifi cally of venous thrombo- sis, severe vasovagal reaction, and endocarditis.[ 4 ]

Suitable contraception should be off ered to all women with heart disease who are sexually active and who either do not yet wish to conceive or for whom pregnancy is not advisable. Any competent young per- son in the UK can consent to medical treatment. If they are under 16 years old their parents or carers should be informed, although if it is judged that providing con- traception is in the best interest of an adolescent who

Contraception in women with heart disease

Mandish K. Dhanjal

2

understands the information given then parental (or carer) consent is not required .

All women with heart disease considering preg- nancy should be off ered preconception counseling. In women with CHD, counseling should be provided by a specialist in adult CHD in tandem with an appropri- ately experienced obstetrician. A risk assessment should be carried out to specifi cally ascertain cardiovascular and cerebrovascular risk factors, history of hyperten- sion, thrombosis, and migraines, smoking status, and personal or family history of thrombophilia, hyperlipid- emia, stroke, and diabetes. A similarly thorough assess- ment is necessary before prescribing contraception .

Th e WHO classifi cation for contraceptives can be extended and adapted to cover the risk of maternal morbidity and mortality resulting from pregnancy in women with specifi c medical conditions, such as heart disease ( Table 2.2 ).[ 5 ]

Fetal consequences should also be taken into con- sideration when discussing whether pregnancy is advisable. Heart disease causing cyanosis can result in chronic fetal hypoxia that signifi cantly reduces the chances of a live birth. A prepregnancy resting arter- ial oxygen saturation of 85–90% is associated with a 45% chance of a live birth, but this drops to only 12%

with oxygen saturation <85%.[ 6 ] Moreover, such a low

oxygen saturation is also associated with a high mater- nal hemoglobin concentration, poor placental perfu- sion, and fetal growth restriction. A growth-restricted baby oft en needs to be delivered preterm, thus increas- ing the risk of neonatal morbidity and mortality .

Classifi cation of cardiac conditions

In general, only the most effi cacious contraceptives are suitable for women with severe heart disease because the consequences of contraceptive failure are far greater for them than for women with a less severe dis- order. Table 2.3 shows various cardiac diseases under each class. Class 2 and 3 cardiac conditions are those with a slightly or signifi cantly increased risk of mater- nal morbidity and mortality.[ 5 ] Individual specialist assessment is required to establish to which class of risk these conditions should be allocated. Combinations of abnormalities or the presence of additional risk factors may further increase the risks of pregnancy.

Preconception counseling is imperative for women with class 4 cardiac conditions. It is inevitable that some women will decide to go ahead with a pregnancy despite the risks to their own health, and their right to do so must be respected and supported. However, when women decide they do not want to become preg- nant, it is essential that the most eff ective appropriate

Table 2.2 Classifi cation of medical illness (e.g. heart disease) according to risk to maternal health if pregnant Class

Risk of maternal morbidity and mortality

resulting from pregnancy with medical illness Counseling required if pregnancy considered

1 No detectable increased risk No contraindication to pregnancy

2 Slightly increased risk Can consider pregnancy

3 Signifi cantly increased risk If pregnancy still desired after counseling, intensive specialist cardiac and obstetric monitoring will be required antenatally, in labor and postnatally

4 Unacceptably high risk Pregnancy not advisable; off er emergency contraception or

termination if pregnancy occurs; if declined care for as class 3 Adapted from Thorne et al. [ 5 ]

Table 2.1 WHOMEC and UKMEC classifi cation and interpretation of medical eligibility for contraceptives

WHOMEC/UKMEC class Eligibility for contraceptives with medical conditions “ABCD” classifi cation

1 No restriction for use A lways usable

2 Advantages of method generally outweigh theoretical or proven risk B roadly usable

3 Theoretical or proven risks generally outweigh advantages C aution/counseling

4 Unacceptable health risk D o not use

UKMEC = UK Medical Eligibility Criteria; WHOMEC = World Health Organization Medical Eligibility Criteria Adapted from World Health Organization and Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare [ 2 , 3 ]

Section 1: Pregnancy Counseling and Contraception

contraceptive agents are recommended and supplied.

If there is failure of regular contraception, then emer- gency contraception should be provided promptly.

Failing this, termination of pregnancy should be avail- able without delay .

Contraceptive agents

Th ere are a range of contraceptive agents suitable for each cardiac condition. Th e one recommended for use should be tailored according to the individual’s particular circum- stances. Th e following points should be considered when deciding on the most appropriate contraceptive agent:

• patient choice

• thrombotic risks of estrogen-containing contraceptives

• hypertensive risks of estrogen-containing contraceptives

• vagal stimulation and bradycardia can occur with insertion of an intrauterine device (IUD)

• infective risks with insertion of an IUD

• bleeding risks for patients on warfarin (copper intrauterine devices [Cu-IUDs], intramuscular injections)

• eff ects of anesthesia

• noncontraceptive benefi ts (e.g. reduction in menstrual bleeding)

• drug interactions

• degree of effi cacy of the method (especially if pregnancy is not advisable) .

Effi cacy of use of contraceptive agents

Very few women use a contraceptive agent per- fectly in accordance with the product instructions.

Most women fall into the category of “typical user,”

Table 2.3 Risk of maternal morbidity and mortality from pregnancy in various cardiac conditions

Class 1: No concerns for pregnancy Class 3 a : Pregnancy has signifi cantly increased risk Uncomplicated, small or mild lesions e.g.

• mitral valve prolapse

• patent ductus arteriosus

• ventricular septal defect

• pulmonary stenosis

Successfully repaired simple lesions e.g.

• patent ductus arteriosus

• ventricular septal defect

• ostium secundum atrial septal defect

• anomalous pulmonary venous drainage

• isolated ventricular extrasystoles and atrial ectopic beats

Mechanical valve Systemic right ventricle b

Following Fontan operation (for tricuspid atresia) Cyanotic heart disease (unrepaired)

Other complex congenital heart disease Aorta 40–45 mm in Marfan syndrome

Aortic disease associated with bicuspid aortic valve

Class 2 if otherwise well and uncomplicated: Can consider pregnancy (slight risk)

Class 4: Pregnancy not advisable Unoperated atrial or ventricular septal defect

Repaired tetralogy of Fallot Most arrhythmias

Pulmonary arterial hypertension of any cause Severe systemic ventricular dysfunction with

• NYHA class III–IV or

• left ventricular ejection fraction <30%

Previous peripartum cardiomyopathy with any residual impairment of left ventricular function

Severe mitral stenosis or severe symptomatic aortic stenosis (valve areas <1 cm 2 )

Aorta dilated >45 mm in Marfan syndrome

Aortic dilatation >50 mm in aortic disease associated with bicuspid aortic valve

Native severe aortic coarctation Class 2−3 depending on individual: Slight/signifi cant risk in

pregnancy

Mild left ventricular impairment Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Native or tissue valvar heart disease not considered class 1 or 4 Marfan syndrome without aortic dilatation c

Aorta <45 mm in aortic disease associated with bicuspid aortic valve Repaired aortic coarctation

Heart transplantation

a If there are other risk factors, pregnancy may carry a class 4 risk

b Congenital heart disease in which the right ventricle supports the systemic circulation c With or without a family history of aortic dissection

NYHA = New York Heart Association

Adapted from Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare and Thorne et al. [ 4 , 5 ]

where they occasionally use the method incorrectly.

[ 2 ] Pregnancy rates for typical users are therefore a better reflection of the efficacy that can be expected from a contraceptive ( Table 2.4 ). There is a paucity of data on pregnancy rates with typical use in the UK; most data are obtained from studies in the USA.

[ 2 ] Only the most reliable contraceptive methods

should be recommended for those with class 3 or 4 risk.

Th e contraceptive methods that will be considered in detail below are those for which fewer than 10% of women conceive in the fi rst year of typical use.

Table 2.5 shows the relative advisability of various contraceptive methods in several cardiac conditions.

Table 2.4 Effi cacy of contraceptive methods with typical and perfect use

Contraceptive method

Women experiencing an unintended pregnancy within fi rst year of use (%)

Typical use Perfect use

No method 85 85

Spermicides 28 18

Withdrawal 22 4

Fertility awareness-based methods 24

Standard days method a 5

Two-day method b 4

Ovulation method b 3

Cap

Parous women 32 26

Nulliparous women 16 9

Sponge

Parous women