A big thanks goes to the members of the Eric Davidson Lab who helped me. The high degree of conservation of repeats is indicative of potential protein binding sites. TAA salts reduce the effect of GC% on T by binding to A:T base pairs.

The decrease in temperature is probably due to the reduced polarity of the solvent (Rees et al., 1993). The identification of a protein that binds with high affinity to a specific region of the repeat element is described. One area that still needs some work is identification of the actual binding site for SpRFA-70.

Sequences of the CyIIIa actin gene regulatory domain specifically bound by sea urchin embryo core proteins. Sequences of the CyIIIa actin gene regulatory domain specifically bound by sea urchin embryo core proteins. SpZl2-1, a negative regulator required for spatial control of the tenito-specific CyIIIa gene in the sea urchin embryo.

Multiple medium temperature washes can be done in steps to ensure all washes are done.

Repeated sequence target sites for maternal DNA-binding proteins in genes activated in early sea urchin development

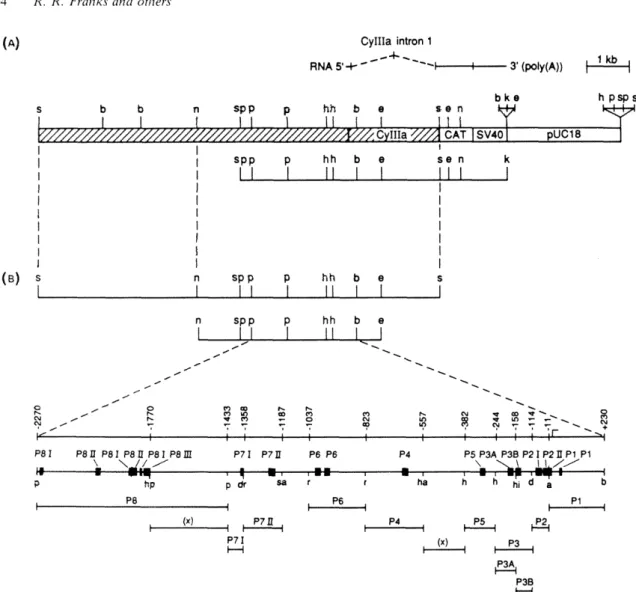

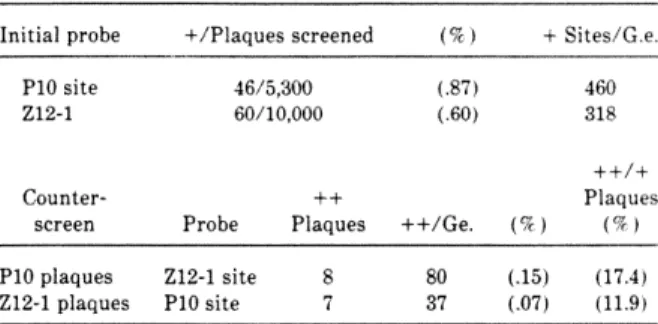

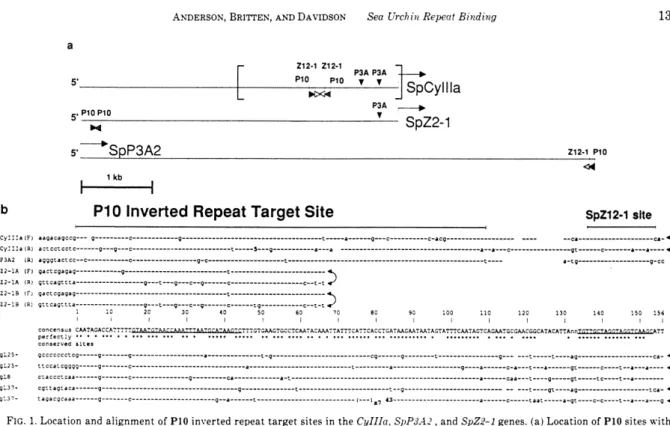

In the CyIIIa gene, the two elements of the P10 inverted repeat target site appear in a particularly interesting arrangement. In the CyIIIa sequence shown (F), nucleotide 1 of the census corresponds to nucleotide 1153 of the regulatory domain of the CyIIIa gene (Thhzk et al., 1990). For the genomic isolates, + and - designations are used to distinguish between the inverted copies of the repeat.

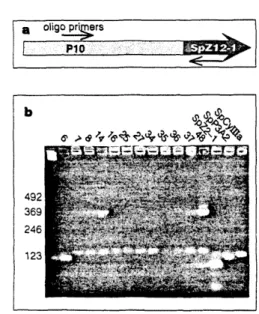

The probe was a DNA fragment consisting of the SpZ2-1 (A) pair of inverted repeat elements shown in Fig. The sequences for some of the same PlO:SpZ12-1 genomic sites a s used for the PCR experiment a r shown in Fig . The exact sequences of the regions amplified by the last three genes are shown in Fig.

Sea urchin embryo gene regulatory factors I. Purification by affinity chromatography and cloning of P3A2, a novel DNA binding protein. Competitive titration in living sea urchin embryos of regulatory factors required for CyIIIa actin gene expression. CyIIIa actin gene regulatory domain sequences specifically bound by nuclear proteins of the sea urchin embryo.

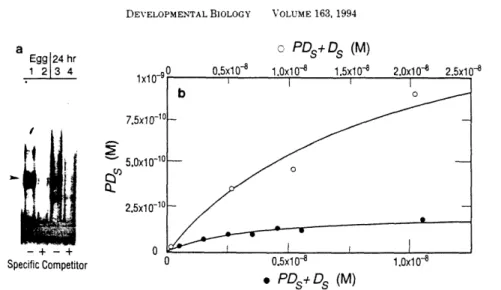

We demonstrated the presence of a high degree of conservation of the specific binding site. For the equilibrium measurements, saturation binding of the probe in the absence of non-specific competitor was used. The Kr of the protein in whole egg extracts for the specific dsDNA site is approximately 2x10'.

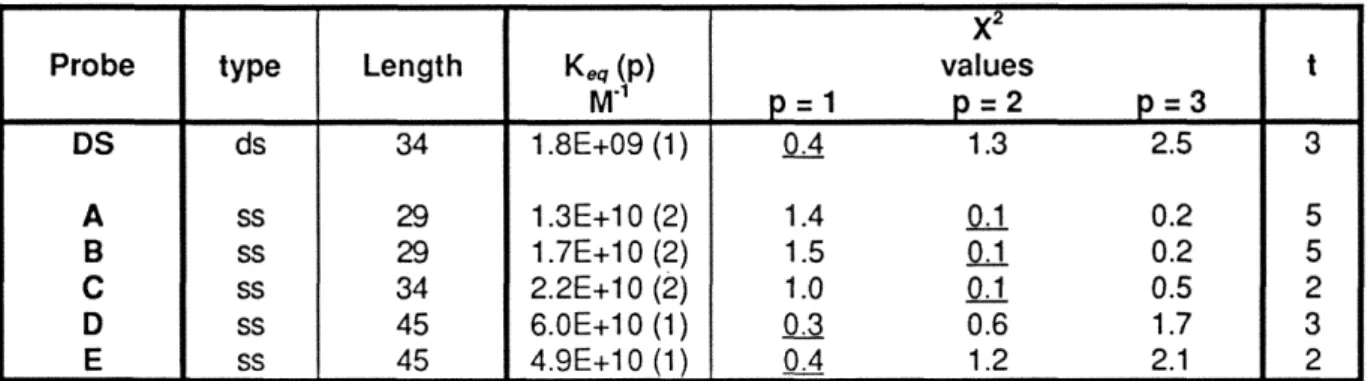

A simple fit of the data from one of several trials can be seen in Fig. To further characterize the SpRFA-70 kD subunit, we measured the equilibrium constants (Keq) for the binding of the protein to short double- or single-stranded DNA probes. These data demonstrate that the protein purified, isolated, cloned and characterized is the sea urchin homologue of the WA 70kD subunit.

Further evidence that the binding factor is SpRFA-70 comes from our findings on the single-stranded DNA-binding activity of the purified protein. The Kr and Po values determined in this measurement are shown in the lower right corner of the graph.

Detection of the SpRFA-70/SpZ12-1 repeat in other species

We searched for the presence of two regions containing these binding sites in the genomes of other organisms. By hybridization to blotted genomic DNA of several species, we show that there are copies of the repeat regions of SpRFA-70 and SpZl2-I in the genomes of three species of Strongylocenrrotus. No significant evidence has been found to suggest that any of these regions are conserved outside of the class Echinoidia.

No significant number of homologous copies of these repeat sections could be detected under these conditions in any of the other genomes tested. Three possible differences in repeat structure can account for this result: the bases at the ends of the sites are not well conserved, the sites are not in close proximity to each other, or the sites are not in the correct orientation for amplification. 2 distinguish the phylogenetic distribution of the repetitive sequence elements that identify our probes from the linkage distribution.

Although the phylogenetic distribution of the SpZ12-1 transcription factor has not been specifically investigated, it is certainly not expected that this factor would be restricted to the genus Strongylocentrotus. Transcription factors and their target sites are generally widespread, as the requirement for co-evolution (ie of the protein's recognition sequence and its DNA target site) will delay evolutionary change; and as Wang et nl. 1995) showed that the Zn-finger binding domain of SpZ12-1 is indeed similar to that of a Drosophila Zn-finger factor Krcppel. The length of the actual SpRFA-70 target site is unknown, although it is a very specific site that is bound very tightly by a single SpRFA-70 molecule per probe fragment (Chapter 3).

2 of this appendix allowed no more than 3 bp mismatches for the probe molecule, we are clearly assessing the presence or absence of repetitive elements in which these two target sites are embedded, not of the sites themselves. Perhaps in this study we are observing an early stage of the basic evolutionary process by which regulatory modules are transported by mobile elements to the cis control regions of genes, endowing them with new regulatory responses. -1, a negative regulator required for the spatial control of the tenitor-specific CyIIIa gene in the sea urchin embryo.

The gray line above this section indicates the position and orientation of the 28 bp. oligonucleotide probe used to detect this portion of the entire repeat. We know that the specific binding site for SpRFA-70 is somewhere within the probe sequence. The black arrow below the SpZ12-1 region indicates the site and position of the 21 bp oligonucleotide probe used to detect this repeat segment.

Competitive titration in living sea urchin embryos of regulatory factors required for expression of the CyIIIa actin gene

Competitive titration in living sea urchin embryos of regulatory factors required for Cyllla actin gene expression. Our objective in the present work was to obtain in vivo evidence of the functional significance of individual CyIIIa protein binding sites. The actual concentration of sequence-specific competitor DNA in the final sample used for injection was measured by slot-blot hybridization using a single-stranded RNA probe.

DNA measurements were made at 24 h after fertilization by a modification of the slot-blot procedure described previously (Flytzanis et al. 1987; Franks et a/. 1988). Alternatively, the Cy1Ila .CAT fusion gene (not shown) described by Flytzanis er al. 1987) was linearized at the SphI site located 2.5 kb upstream of the CyIIla transcription start site. 2 these values were used for normalization of CAT enzyme content in embryos within each experimental series.

None of these subfragments showed any competitive function in our hands (results not shown), nor did any subfragments extend 5.3 kb upstream of the SphI site (see Fig. 1A). An a' value of 1.0 would indicate that the competitive effect of the subfragment is equal to that of the fragment containing the entire regulatory domain. Molar Ratio: Concurrent DNNCyllIIa-CAT DNA FIG. 3. 117-vii-o competition by sub-elements of the CyIEla 5'-regulator region in transgenic embryos.

The kinetics of the response can be adjusted to the shape expected for a satiety phenomenon. Otherwise, the factors would spread independently among them if redundant copies of the regulatory domain are introduced. On the other hand. ttrc almost complete failure of the P3A. P6 and P711 subfragments that compete effectively cannot simply be explained in the same way.

In the case of factors P8 and P5, for example, which at first sight appear to function redundantly, i.e., we think of the CyIIIa regulatory system as a logical developmental shift, in the sense that it converts the individual's multielement model . . N (1988) Transcription from each of the Drosophila actln 5c leader exons IS drnen b j a separate functional gene promoter.