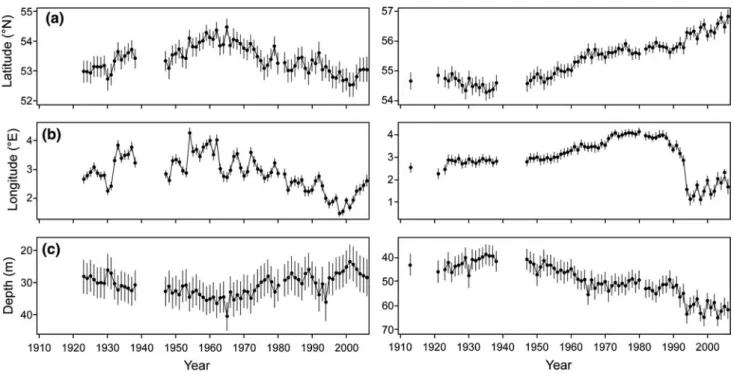

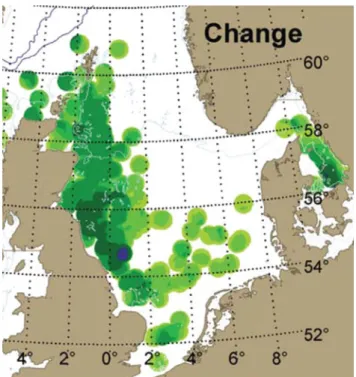

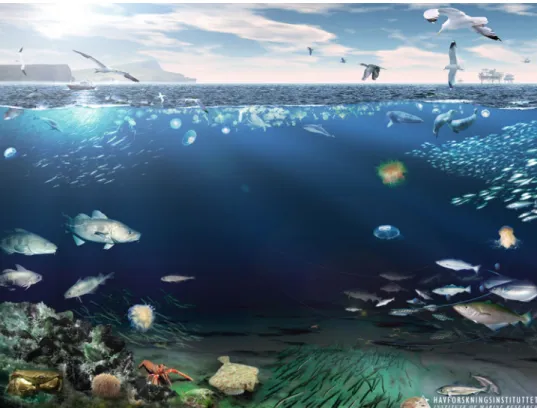

Phenological changes (Edwards and Richardson 2004) as well as biogeographic shifts (Beaugrand et al. 2009) have been observed in North Sea plankton. Benthic fauna in the North Sea are generally categorized as northern, southern or cosmopolitan (Glémarec 1973; Rachor et al. 2007).

Fish

Herring in the North Sea has experienced two periods of weak recruitment in recent decades. The available habitat for plaice in the North Sea may decrease due to climate change (Petitgas et al. 2013).

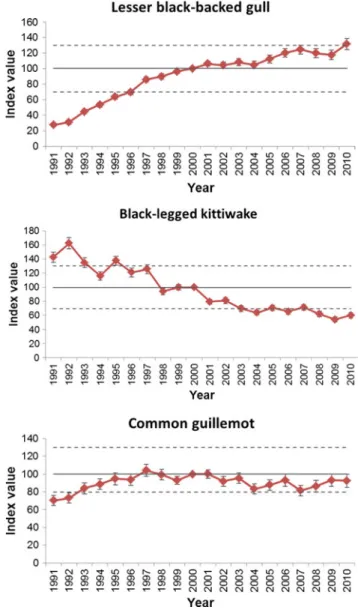

Seabirds

The species is a very important prey item for the small fish favored by seabirds (Beaugrand et al.2003). In particular, the recruitment of small sandeel in the North Sea is strongly positively correlated with the abundance of C.fin-marchicus (van Deurs et al. 2009).

Marine Mammals

Shifts northwards, probably out of the North Sea, may also be due to changes in the structure of the zooplankton community, acting through main prey species such as monkfish (Frederiksen et al. 2013). In the shallow southern North Sea, the number of porpoises appears to have increased since the early 1990s (Hammond et al. 2002;

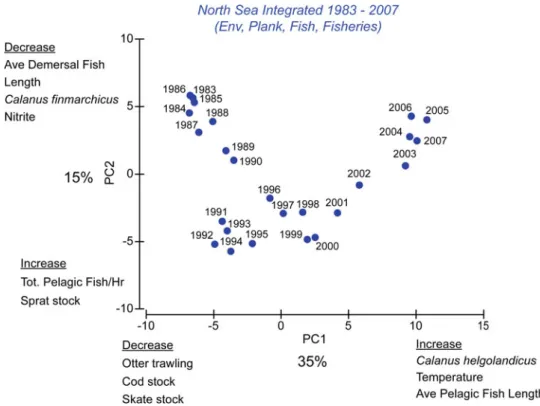

Ecosystem Effects

Indeed, climate-related changes in plankton phenology (Section 8.2) are seen as a contributing factor to the decline of North Sea cod stocks, although overfishing also plays an important role (Nicolas et al. 2014). Copepod biomass, euphausiid abundance and prey size have also been shown to influence early life-stage survival of North Sea cod (Beaugrand et al.2003).

Brief Synthesis and Reflection on Future Development

Reid PC, Edwards M (2001) Long-term changes in North Sea pelagos, benthos and fisheries. This chapter examines the impacts of climate change on natural coastal ecosystems in the North Sea region.

Introduction

Geomorphology of Sandy Shores and Coastal Dunes

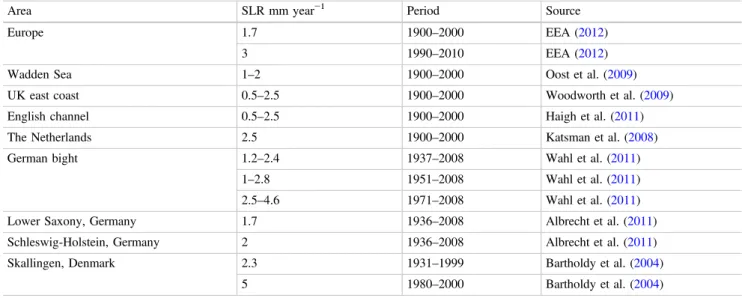

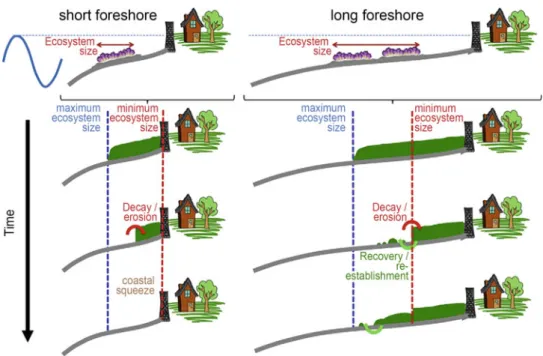

Recent high-level projections suggest that an SLR of 1.25 m in the North Sea may be possible by 2100 (Katsman et al. 2011), although the exact magnitude of the increase depends strongly on the underlying modeling assumptions. Quantitative prediction of the response of sandy beaches to climate change-induced effects at the margin.

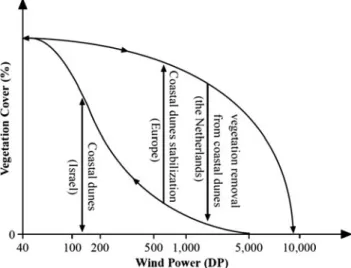

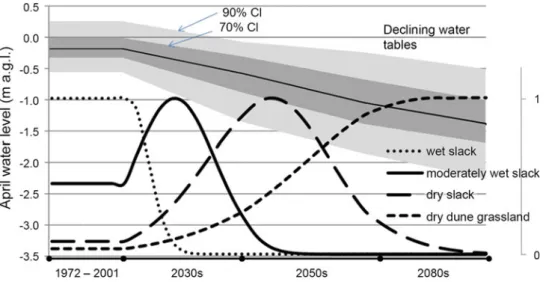

Ecology of Sandy Shores and Dunes

They are often nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) co-limited, and sand dune vegetation is dependent on hydrological regime (water table and seasonal and interannual fluctuations) and groundwater chemistry, especially buffering capacity (Grootjans et al. 2004). The amount of soil organic matter mineralization is likely to increase due to higher temperatures (Emmett et al. 2004) and a prolonged growing season (Linderholm 2006) in the majority of North Sea coastal areas, especially in the northern part.

Fine-Grained Sediment Transport and Deposition in Back-Barrier Areas

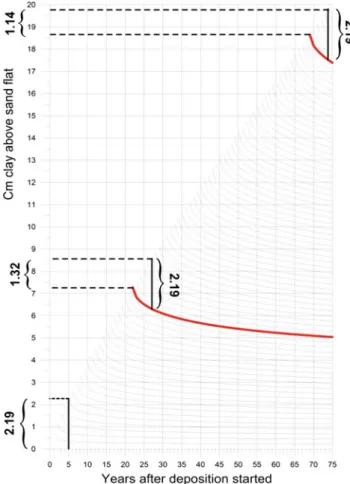

Once deposited on the salt marsh surface, fine-grained sediment consolidates due to self-compaction (e.g. Cahoon et al.1995,2000). Most of it is mobilized from adjacent sand tides and deposited in the salt marsh during storms. The map is overlaid on an aerial photo visible outside the modeled area and in the salt marsh streams (after Bartholdy et al.2010b).

Estuaries: Geomorphology and Sediment Transport

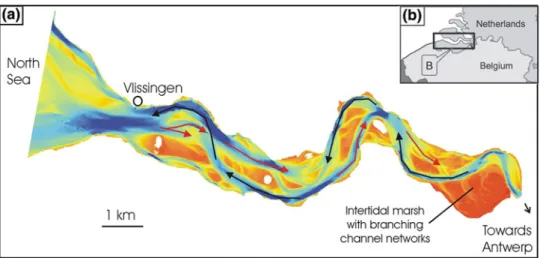

Because of this, the salt marshes in the Wadden Sea quickly rise above the highest astronomical tide (HAT), something that never happens in Georgia (Bartholdy 2012). The existence of an ETM is well-documented for most estuaries in the North Sea region (eg Uncles et al. 2002) and can have important implications for the estuarine ecosystem because it controls turbidity. A particular example of mitigation of climate and human-caused impacts is the conversion and restoration of previously reclaimed land to flats and intertidal marshes in the UK (so-called managed coastal regeneration schemes, such as in the Humber and Blackwater estuaries) (French) 2006b ) and Belgium (Sigma plan in the Scheldt estuary) (Maris et al. 2007).

Salt Marshes

Currently, a decrease in the pioneer zone and an increase in the high marsh zone in the Wadden Sea have been reported (Esselink et al. 2009). The letters A, B, C and D indicate the most important factors considered in the review (after Nolte et al.2013a). However, at the scale of the salt marsh, data from repeated vegetation mapping shows a certain decrease in the sea sofa community (Dijkema et al. 2011).

Coastal Birds

However, this finding is in contrast to the aforementioned results of soil subsidence due to gas extraction, which showed no changes in vegetation (Dijkema et al. 2011). More broadly, there have been few clear patterns in the observed changes in shorebird distributions that have been largely attributed to global warming (Ens et al. 2009). Projections for European-scale coastal breeding populations have also been made based on climate envelope models with mostly northward shifts in shorebird distributions (Huntley et al. 2008).

Conclusions

Grabemann I, Weisse R (2008) Impact of climate change on extreme wave conditions in the North Sea: and ensemble study. Jensen K (2013b) Does livestock grazing affect the resilience of salt marshes to sea level rise in the Wadden Sea. Van Straaten LMJU, Kuenen PHH (1957) Accumulation of fine-grained sediments in the Dutch Wadden Sea.

Introduction

Climate Warming and Impacts on Lake Physics

Research in lakes in the North Sea area has demonstrated the occurrence of many of the phenomena mentioned in the previous section. In the case of Great Britain, the Lamb synoptic weather classification system (Lamb 1950) has proved useful. As for winter lake surface temperatures, the duration of ice cover on lakes in the North Sea region also appears to be strongly related to the NAO.

Catchment – Lake Interactions

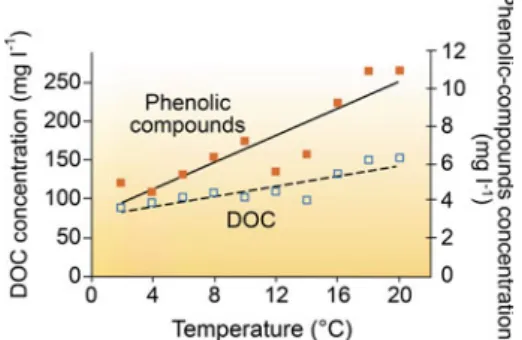

For lakes in Sweden, the ice-out time is strongly related to the winter NAO, while the ice-out time shows a weaker relationship to the autumn NAO (Blenckner et al. 2004). Atmospheric deposition of nitrogen and sulfur will add to these climate-related impacts on ecosystems (Wright et al. 2010). The well-documented increase in dissolved organic matter in boreal lake ecosystems is one of the most obvious indirect effects (Monteith et al. 2007).

Ecosystem Dynamics

Furthermore, a dominance of filamentous green algae rather than phytoplankton seems possible under high temperatures (Trochine et al. 2011). For large areas in Northern Europe, mass occurrences ('general growth') of the macrophyte Juncus bulbosus have been recorded (Moe et al. 2013). Increased N deposition in interaction with increased export of DOM can promote export of N2O (Hong et al. 2015).

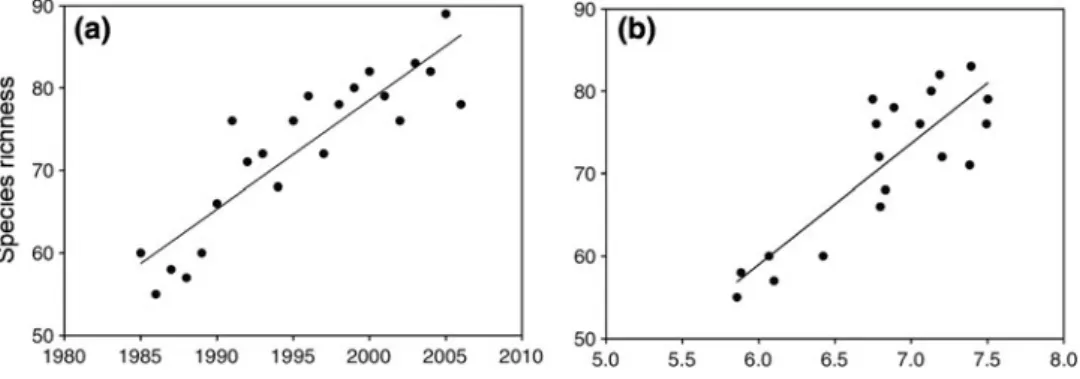

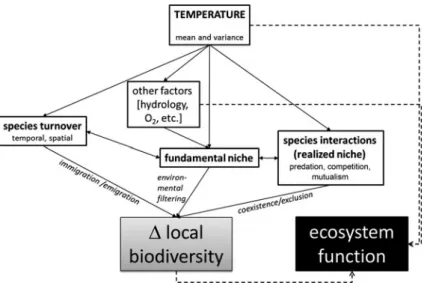

Biodiversity

Climate-induced changes in biodiversity are very likely to influence changes associated with other anthropogenic pressures, such as eutrophication (Moss et al. 2009). A recent review made a strong case for including temperature variability in climate change experiments (Thompson et al. 2013). Laboratory experiments also showed a faster change in species composition with increasing temperature (Hillebrand et al. 2012).

Importance of Temporal Scale

A closer look at sub-hourly measurements showed that the rate of increase in the daily minima (night water temperature) exceeded that of the daily maxima (day water temperature) (Wilhelm et al.2006). Day-to-day variation in respiration appears to be common in lakes worldwide, including those in the North Sea region (Solomon et al. 2013). This difference was due to the thermal stratification pattern that was only critically intense in 2006 (Huber et al.2012).

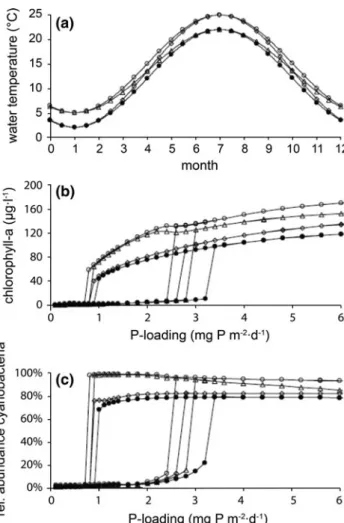

Modelling

Modeling studies of the long-term effects of climate change in Northern Hemisphere temperate lakes (e.g. Elliott et al. 2005; Mooij et al. 2007; Trolle et al. 2011) generally imply that total phytoplankton biomass has is likely to increase, and that cyanobacteria will become a more dominant feature of the phytoplankton species composition. The simulations include four scenarios: a control (closed circles), a year-round temperature increase of 3 °C (open circles), an increase in the summer maximum temperature of 3 °C but no change in the winter minimum ( open diamonds ), and an increase in winter minimum temperature of 3 °C, but no change in summer maximum (open triangles) (adapted from Mooij et al.2007).

Conclusion

George G, Hurley M, Hewitt D (2007b) The impact of climate change on the physical characteristics of the larger lakes in the English Lake District. Livingstone DM (2003) Impact of secular climate change on the thermal structure of a large temperate Central European lake. In general, the effects of recent climate change on land ecosystems within the North Sea region are still limited.

Introduction

General Patterns and Processes

Together with the slight expected increase in the duration of the dry periods (see Chapter 5 and Jacob et al. 2014), vegetation productivity in the southern North Sea area could therefore decrease. Furthermore, water availability also strongly determines forest productivity in south-eastern Britain (Broadmeadow et al.2005), and not strictly speaking in the southern part of the study region. Because the area south of the North Sea area is generally richer in species (e.g. Thuiller et al. 2005), biodiversity in the North Sea area could even increase.

Forests

The decline was particularly strong among nectar-producing herbs, which likely had negative consequences for pollinators (Wesche et al. 2012). Projections of potential climate-induced transient shifts in broadly defined forest types indicate only moderate changes in the North Sea region by 2100 (Hickler et al.2012). Many European tree species have not yet filled their potential climatic niche in Europe due to distribution limitations (Svenning and Skov2004; Normand et al.2011).

Grasslands

Observational studies (Honnay et al. 2002) and modeling studies (Skov and Svenning 2004) suggest that this is probably due to dispersal limitation due to fragmentation of lowland forest habitats. Hickler et al. 2012), whereas environmental conditions for the commercially important Norway spruce will become less favorable (Pretzsch and Dursky2002; Schlyter et al.2006; However, as shown by Smith et al. 2007), this assumption was uncertain and lacked clear empirical evidence.

Heathlands

Oliver et al.2012). indicating the increasing importance of P limitation due to warming and drought. Similarly, in the same warming and drought experiments, Jensen et al. 2004) found largely weak or inconsistent responses in key soil processes such as decomposition, respiration, and N mineralization. Berry et al. 2002) that eco-thermal animal species in heathlands can benefit from climate warming at the northern edge of the range.

Mires and Peatlands

Climate change is expected to have a major impact on biotic processes in peatlands (e.g. Heijmans et al. 2008; Charman et al. 2013). The mobilized DOC can be mineralized and released to the atmosphere as CO2 (e.g. Silvola et al. 1996; On the other hand, land use-related effects on peatlands often make them more vulnerable to climate change impacts (e.g. Parish et al. 2008) ).

Inland Ecosystems and the Wider North Sea System

The magnitude of DOC fluxes in rivers is related to the storage of organic matter in their catchment soils (eg Hope et al.1997). In Dutch managed peatlands, subsidence continues at up to one centimeter per year (Hoogland et al. 2012 and references therein). The need for ever deeper drainage increases the rise of sulfate-rich brackish or saline water (Hoogland et al. 2012).

Summary

Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Hulme PE (2005) Adapting to climate change: is there an opportunity for ecological management in the face of a global threat. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.