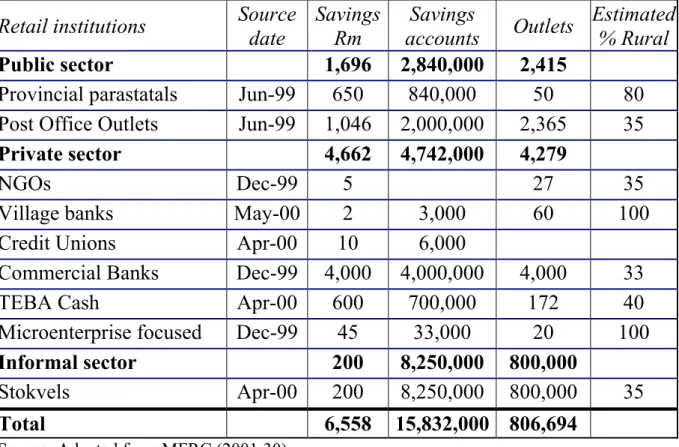

Murray Leibrandt is Professor in the School of Economics at the University of Cape Town and Director of SALDRU within the CSSR. James Levinsohn is Associate Dean of the Ford School of Public Policy, Professor in the Department of Economics at the University of Michigan (USA) and SALDRU Research Fellow within the CSSR. Income concentration in accessing the complementary package of formal financial services excludes households in the lower deciles from formal financial services.

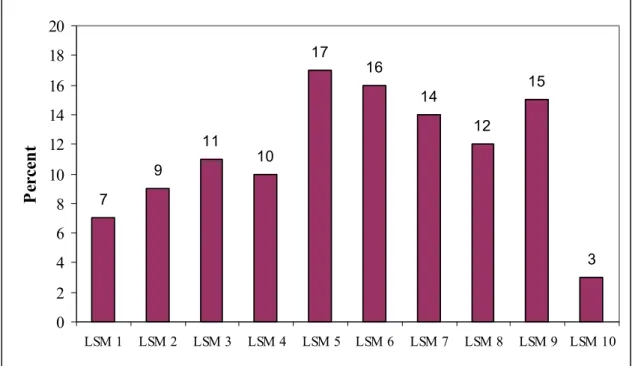

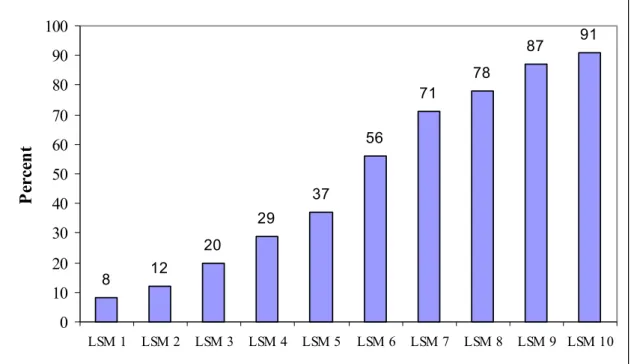

This increased awareness of the role of access to financial services in reducing poverty in South Africa echoes developments in the contemporary international poverty literature. In 2000, only 1% of household spending in the bottom quintile went toward insurance, pensions, savings, and investments compared to 11.9% in the top quintile. Access to formal bank savings increases from 9% in the lowest income decile to about 80% in the highest decile.

Of those in the economically active age group (16 to 64 years), 29.4% had a bank or savings account. The negative impact of the absence of financial services in the area is illustrated by the fact that three-quarters of respondents referred to the absence of banks when asked what problems residents of Ntuli district were experiencing.”

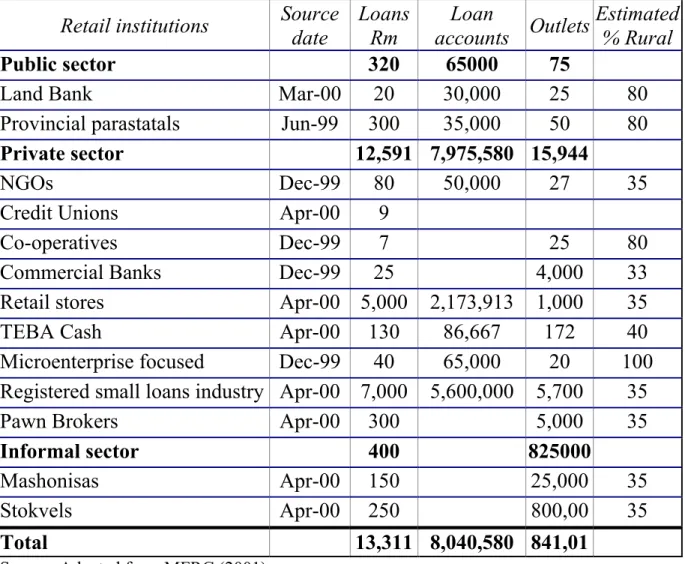

Borrowings

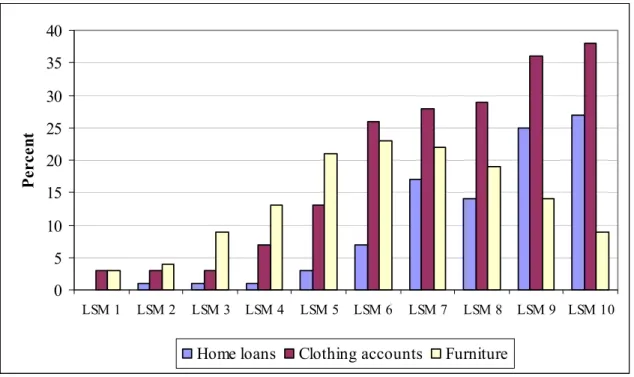

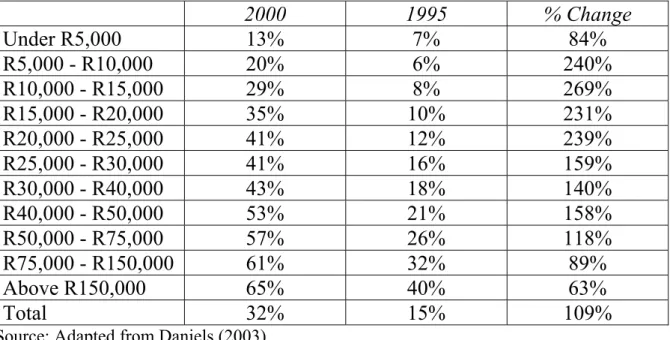

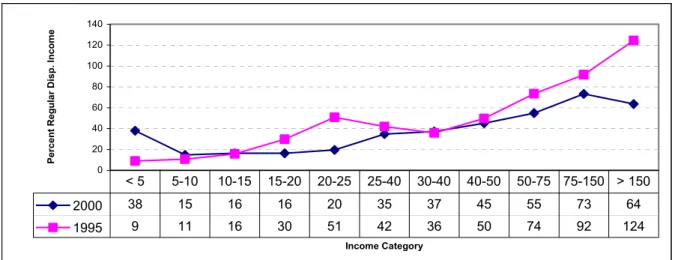

The only significant and physical source of cash in the area was at the pension payment points for one day a month. The proportion of households with positive debt increased for all income categories with increases of more than 200% in the R5 000-R25 000 income categories and increases of more than 100% for the R25 000-R75 000 income categories. Regarding households with positive debt, Daniels (2001a, 2001b and 2003) found that poorer households had lower levels of debt compared to richer households in 1995 and 2000, which "may be partly explained by a lack of access to financial banking instruments in the sector …, substantiated by low levels of collateral among the poor” (Daniels 2001a: 6).

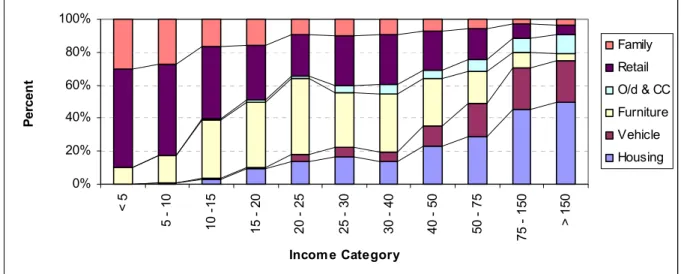

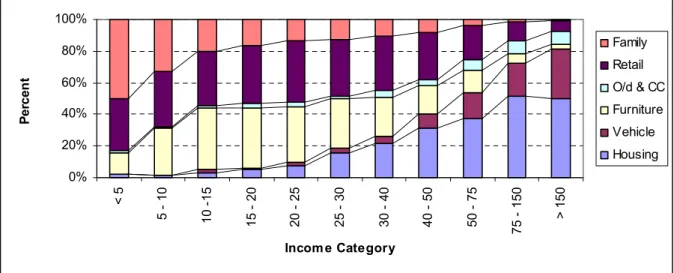

It decreased the most in the wealthiest income group, where debt was halved. In the lower income categories, debt originated mainly from furniture stores, retail establishments and families, meaning that poorer individuals had significant amounts of debt at high interest rates for consumables rather than assets. Households in the R10,000–R25,000 category were characterized by a large proportion of debt acquired from furniture shops, together with a large proportion of total consumption devoted to expenditure on basic needs.

Households in the income category above R150,000 were considered vulnerable as they had the highest levels of indebtedness and the lowest levels of liquidity. There was an increase in home loans and retail debt for households in the R75,000-R150,000 category. The penetration of retail debt in the lower income categories and the importance of furniture and appliance debt in the middle income categories is evident.

Since the surveyed households were largely cut off from accessing financial resources, we would expect their ability to smooth consumption over their lifetime and in the face of negative shocks to be limited. She also found that there were no differences in the incomes of households with and without access to finance across the age of household heads. Rasmussen (2002) argues that "this is in line with the reasoning of the theory of precautionary behavior in that households without access to finance must maintain lower consumption in order to retain sufficient resources in the event that the household is hit by a future shock and cannot borrow to overcome the effects of that shock”.

Both of these are short-term coping actions that can lead to increased deprivation in the long-term. Dallimore (2003) found that just under half of respondents indicated that they had borrowed money, food or goods in the previous 12 months. Ardington (1999) found that without access to financial institutions in the area, the incidence of borrowing was very low.

Insurance

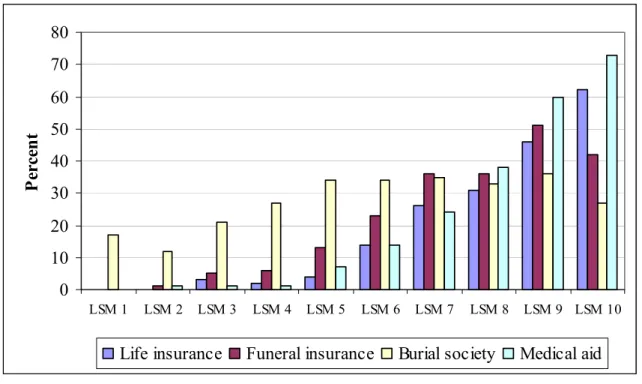

Only 10% of households mention borrowing money as a coping strategy for the "death of a household member", while 24% of households borrowed money to cope with serious injury or illness. Life insurance Funeral insurance Funeral society Medical fund Source: AC Nielsen Futurefact Marketscape Survey 2002 (Adapted from Porteous 2003). Ardington et al (2003) found that an African household was approximately 29% less likely than a White household to purchase insurance.

Depending on race and other demographic variables, higher income is associated with higher insurance use. Examining specific forms of insurance, they find that, unlike other types of insurance, after controlling for income and other demographic variables, African American households are more likely to purchase funeral insurance than white households. As with other types of insurance, a higher per capita income is associated with a higher probability of taking out funeral insurance, but the size of the coefficient on income is much smaller than with other types of insurance.

Although estimates vary, it is clear that funeral homes in particular are an integral part of the risk management strategies of low-income households in South Africa. The impact of the AIDS pandemic on social capital must be included in any vulnerability assessment. Maluccio et al (2000) used the KIDS survey to examine the effect of social capital on household expenditure.

Less than 3% of households had used insurance when faced with "the death of a household member" and less than 2% for each. Rasmussen (2002) examined the effect of the range of coping strategies adopted on the probability of living in poverty in 1998. Controlling for household expenditure in 1993, she found that "only the use of insurance schemes shows very clear beneficial effects, but only for better-off households, as there were no data points available for poorer households” (Rasmussen 2002:79).

The use of insurance as a coping strategy showed a statistically significant impact in preventing households from falling into poverty and helping households move out of poverty.

Summary of Key Findings and Policy Implications

There is therefore evidence of the emergence of important new institutions in the financial services market. The growth of the microcredit sector has improved access to financial services, with the number of positively indebted households more than doubling from 1995 to 2000 (Daniels 2003). The fact that the lack of income drives a wedge between demanders and suppliers in the financial services market has very general implications for public policy.

Ardington et al (2003) show that access to financial services is only beginning to reach 50% of households in the 7th, 8th and 9th deciles respectively for savings insurance and debt. This implies that even a highly successful poverty-targeted matrix of macro and micro policies will not bring too many households into the ambit of the formal financial services market as currently constituted. Somewhat in contrast, financial liberalization and the lack of formal financial services for the lowest income deciles resulted in the phenomenal growth of the microfinance sector in the 1990s.

The MFRC (2001) suggests a comprehensive assessment of both the demand and supply sides, at least annually, to enable regulators and the state to monitor the provision of financial services to the poor. The exclusion of the majority of South African households from formal financial services is important because the literature shows that poorer households currently rely on informal loans such as household loans to facilitate consumption. Ardington et al (2003) show that the lack of access to other financial services for these households means less education expenditure, less healthcare expenditure and they are more likely to have gone hungry in the past year.

Unfortunately, as mentioned a few times in this paper, the available data does not provide information on how the financial services providers operate. Apart from these limitations, a number of policy options to increase access to formal financial services for poorer households, particularly in rural areas, are worth exploring. If the government committed itself to depositing all social grants and civil service salaries into accounts, the banks might be able to recoup the costs and extend a full range of financial services to the whole community.

The commission saved in current and future grant money payments would go significantly toward covering the infrastructure costs needed for facilities that provide a wide range of financial services to the entire rural population."

2003) “Household Indebtedness in South Africa 1995 and 2000”, Draft Report to the Microfinance Regulatory Council, HSRC, Pretoria. 2003) “Savings versus Credit: A Comparison of Coping Strategies of Poor Households in Rural KwaZulu-Natal”, Unpublished Report, Durban:. Unpublished report, Durban: Development Research Africa, February Assessing Vulnerability to Poverty”, paper prepared for DFID, (see www.economics.ox.ac.uk/members/stefan.dercon/).

1999) "Social protection as social risk management: conceptual foundations for the social protection sector strategy paper", Journal of International Development. INTERNATIONAL LABOR OFFICE (2001) "Women Organizing for Social Protection: The Independent Women's Union Integrated Insurance Scheme", International Labor Office, Geneva. NORTON,A.(1997) "A Difficult Life": The Perceptions and Experience of Poverty in South Africa, Social Indicators Research, 41(1-3), July.

MFRC (2001) “Report on the impact of customer credit and debt”, Micro-Finance Regulatory Council, Johannesburg. A Preliminary Inquiry into Financial Service Co-operatives in South Africa', Economic Society of South Africa International Jubilee Conference, 13-14 September 2001, Glenburn Lodge. 2003) “The landscape of access to financial services in South Africa”, Labor Markets and Social Frontiers No. 3, South African Reserve Bank, Pretoria.

An empirical study of coping with shocks among black households in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. Unpublished Master's Thesis, University of Copenhagen, Denmark. Selected Findings and Comparisons from the October 1995 and October 2000 Income and Expenditure Surveys”, Pretoria. 2002) “Vulnerability: A Quantitative and Qualitative Assessment”, Guatemala Poverty Assessment Program, World Bank, Washington D.C. Risk, Trust and Commercialization”, Annual Convention of the Actuarial Society of South Africa.

The Cases of South Africa and Mozambique", Research Report, nr. 48, School of Development Studies, University of Natal-Durban.

The Centre for Social Science Research

Working Paper Series