THESIS

EVALUATION OF LAND SUITABILITY FOR

SELECTED LAND UTILIZATION TYPES USING

GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEM TECHNOLOGY:

(CASE STUDY IN BANDUNG BASIN WEST JAVA INDONESIA).

*

.L

. -.

ISMAIL HJ. HASHIM

P36500003

GRADUATE PROGRAM

In the name of

f

l h h s. w. t, Most Gracwus a d M o s t Mercz&L

Verib, with every hardship, there is r e l i j

Therefore, when you are free from strive hard

l o the Lordyou shouliiturn allattentwns.

( G e H o b ~ u r ' a n :

f

lInshirah 6-8).

0

Manknd! Worship your L o r i Who has createdyou and those 6efore you

so that you may wardoff(mQ. Who hath appointedthe earth a resting-

plhce foryou, andthe s b

a canopy, causes water to pour downfrom the s b ,

there6y producing fruits as foodfor you.

f

nddo not set up rivab to A l h h

when ye know

(6ette9.

(The H o b Qurhn 2:21-22).

f

l[hh turns over the night and ttie day;

Most sure4 there is a lksson in this for those who have sight.

( G e

H o b Qur'an 24:44).

f

ndwith Him are the k q s of ttie unseen treasures, none knows them 6ut

He; a d N e knows what

ir

in the [hndandthe sea, andthere falb not a lkaf

DECLARATION LETTER

I, Mr. Ismail bin Hj. Hashim, hereby declare that the thesis title:

EVALUATION OF LAND SUITABILITY FOR SELECTED LAND UTILIZATION TYPES USING GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEM TECHNOLOGY (CASE STUDY IN BANDUNG BASIN WEST JAVA INDONESIA),

contains correct results from my own work, and that it have not been published ever before. All data sources and information used factual and clear methods in this project, and has been examined for its factualness.

THESIS

EVALUATION OF LAND SUITABILITY FOR

SELECTED LAND UTILIZATION TYPES USING

GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEM TECHNOLOGY:

(CASE STUDY IN BANDUNG BASIN WEST JAVA INDONESIA).

ISMAIL HJ. HASHIM

P36500003/MIT

A THESIS SUBMITTED TO GRADUATE PROGRAM OF BOGOR AGRKUL TURAL UNIVERSITY INDONESL4 INFULFILL THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN INFORMA TION TECHNOLOGY FOR

NA TURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT.

GRADUATE PROGRAM

In the name of Allah s.w.t, Most Gracious and Most Merciful.

Firstly, I would like to express my sincere thanks and faithful appreciation to SEAMEO BIOTROP for awarding me the scholarship of this Master of Science program. Heartfelt appreciation is also extended to Dr. Ir. Handoko, Director of the Information Technology program, for accepting me in this program and for providing academic assistance.

I would like to express my sincere appreciation to Department of Agriculture and Department of Public Services, Malaysia for giving me financial support and approval of my study leave to undertake this valuable study program.

I would like to express my sincere thanks to external examiner Prof. Dr. Ir. Uup Sjafie Wiradisastra, MSc for sharing his constructive comments and expertise of this project.

I am greatly indebted to Dr. Ir. I Nengah Surati Jaya, my supervisor, for leading the study, for his keen constructive comments, generous support of knowledge and his assistance through critical review of successive drafts chapter by chapter.

I am also greatly indebted to Dr Ir. Iwan Gunawan, MSc, my co-supervisor, for his assistance, constructive comments, sharing valuable expertise and scrupulous guidance to complete this project.

I would also like to thank Center for Soil and Agroclimate Research and Mr. Marwan Hendrisman, SP. 1, my personal supervisor from Puslitbangtanak, for providing generous support of data, guidance and valuable references of the present land evaluation knowledge in Indonesia.

I would like to thank all my instructors who have given me the information technology knowledge, shared experiences and for their kindness of taking care and helping me throughout program. Furthermore, thanks to my classmates. I am very appreciated.

I want to thank all person who may not have been mentioned here, but have contributed in the conduct of this study. This thesis would not have been possible if not through the kind assistance and technical support of several individuals and organizations. I would, therefore, like to take this opportunity to extend my sincerest appreciation to them.

My special thanks to my mom Hjh. Minah Kidon, my father Hj. Hashim Abu, my sister Norhayati, my brothers' family, Jalil, Khairudin, Kamaruddin and Abu Bakar for their prayers, understanding, moral support and encouragement.

APPROVAL SHEET

Research Title Evaluation of Land Suitability for Selected Land Utilization Types using

Geographic Information System Technology:

(Case Study in Bandung Basin West Java Indonesia)

Student Name ISMAIL HJ. HASHIM

Student ID Nrp P36500003

Study Program : Master in Information Technology for Natural Resources Management

Thes-by

the Advisory

Board:

\

Dr. Ir. I Nenpah Surati Java Supervisor

Dr. Ir. Iwan Gunawan, MSc Co-supervisor

Head of Study Program, e Graduate Program,

3-yLw-j

Dr. Ir. Handoko

Evaluation of Land Suitability for Selected Land Utilization Types using Geographic Information System Technology:

(Case Study in Bandung Basin West Java Indonesia) By Ismail Hj. Hashim

Abstract

This thesis aims to build a model of land suitability mapping of rural areas integrating

land evaluation procedures with decision makers' preferences within a Geographic

Information System (GIs) environment. Automated land evaluation system (ALES), Arc

Info TM and the ArcView TM were used to build the land evaluation (LE) model. A

strategy was adopted to integrate the land evaluation model within the GIs. The method

consisted of five steps: ( I ) design of land mapping units (LMUs) @om available maps

(geology, landform, slope, soil, and existing land use) and their attributes in a G I s

environment; (2) diagnostic of proposed land utilizations types (L UTs) and their

requirements; (3) land suitability analysis through matching between LMUs and the

LUTs assessed by ALES; (4) export of the output of LE to a spreadsheet program and

input to a relational database (socio-economic); and (5) presentation of land suitability

maps through joining the tables between the output of land suitability analysis and the

LMUs within a G I s environment. From the study of this research, its shows that most of

Bandung Basin land mapping units meet the requirements to cultivate the selected land

utilization types. This research also developed an automated process of the land

suitability analysis through the integration of the ALES and the GIs. The model was used

to evaluate and produce land suitability maps for seven selected land utilization types of

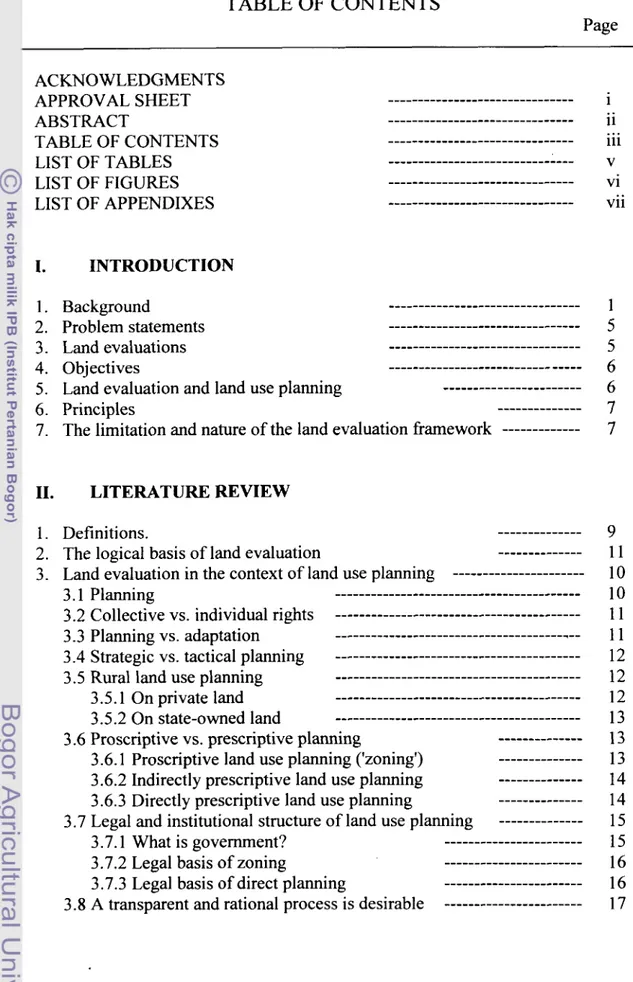

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS APPROVAL SHEET ABSTRACT

TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES LIST OF FIGURES LIST OF APPENDIXES

... 1

. .

... 11

. . .

... 111

...

v... vi

...

viiI. INTRODUCTION

1. Background ... 1 2. Problem statements ... 5 3. Land evaluations ... 5 4. Objectives

...

6 5. Land evaluation and land use planning...

66. Principles

---

77. The limitation and nature of the land evaluation framework --- 7

11. LITERATURE REVIEW

1. Definitions. ---

2. The logical basis of land evaluation --- 3. Land evaluation in the context of land use planning ...

3.1 Planning ... 3 -2 Collective vs. individual rights ... 3.3 Planning vs. adaptation ... 3 -4 Strategic vs. tactical planning ... 3.5 Rural land use planning ... 3.5.1 On private land ... 3.5.2 On state-owned land ... 3.6 Proscriptive vs. prescriptive planning

---

3.6.1 Proscriptive land use planning ('zoning') --- 3.6.2 Indirectly prescriptive land use planning

---

3.6.3 Directly prescriptive land use planning --- 3.7 Legal and institutional structure of land use planning ---3.7.1 What is government?

...

3.7.2 Legal basis of zoning...

3.7.3 Legal basis of direct planning ...4. The aims of land evaluation for development purpose

---

4.1 Levels of intensity and approaches ...4.1 .1 Levels of intensity

...

4.1.2 Two-stage and parallel approaches to land evaluation---

5. Automated Land Evaluation System ...111. MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Times and location of the study area ... 2. Data sources ... 3. Hardware and Software ... 4. Methods ...

4.1 Design of land mapping units --- 4.2 Diagnostic of proposed land use types --- 4.3 Land mapping units ...

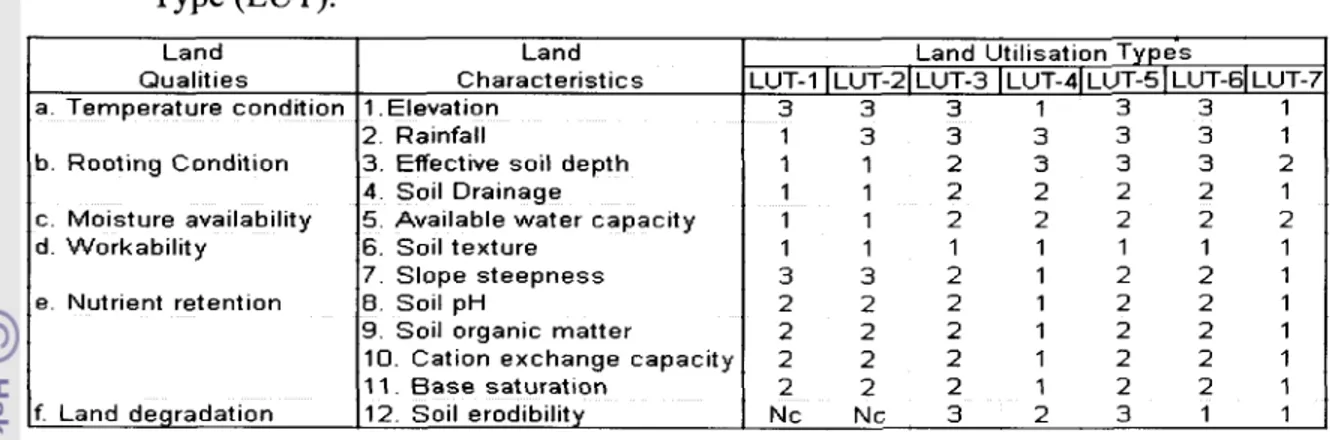

4.4 Selected land utilization types ... 4.5 Relevant land qualities and characteristics for selected

land utilization types ...

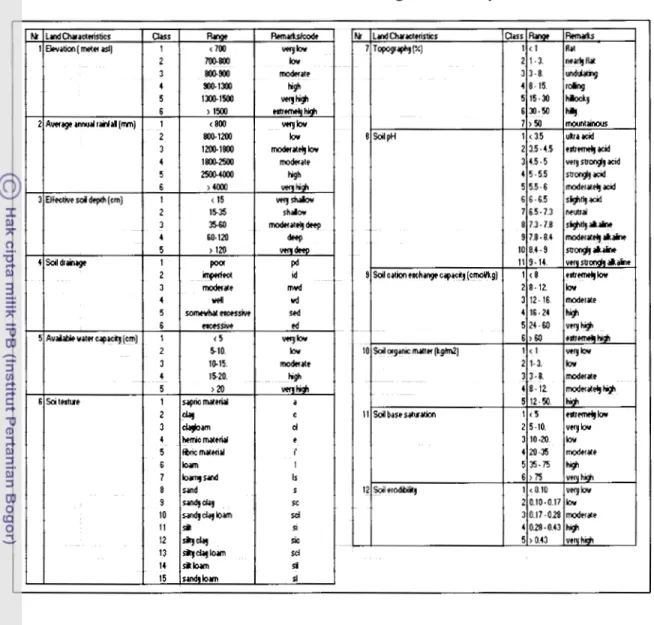

4.6 Land characteristics ratings

...

4.7 Economic inputsloutput of selectedland utilization types ... 4.8 Implementation of automated land evaluation system --- 4.9 Presentation of the land suitability maps ---

IV. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

1. Land evaluation ... 2. Digital land mapping units and analysis of existing

land use types ... 3. Land suitability analysis ...

4. Benefitlcost ratio (BCR) and gross margin (GM)

---

V. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATION

1. Conclusions

1.1. Physical land suitability

...

1.2. Area of physiographic unit ...1.3. Soil erodibility ... 1.4. Economic suitability ...

2. Recommendations ...

LIST OF TABLES

Contents Page

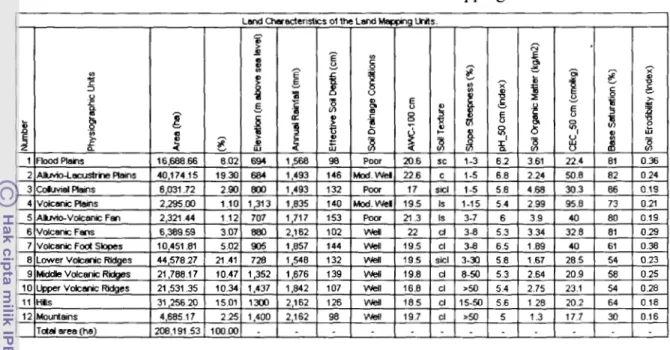

Table 1. Physiographic units with associated land characteristics. --- 3 1

Table 2. Relevant land qualities and land characteristics for --- 3 4 Selected Land Utilizations Types.

Table 3. Land characteristics rating of the study area. ... 3 5

Table 4. Land characteristics of the Land Mapping Units. ... 39

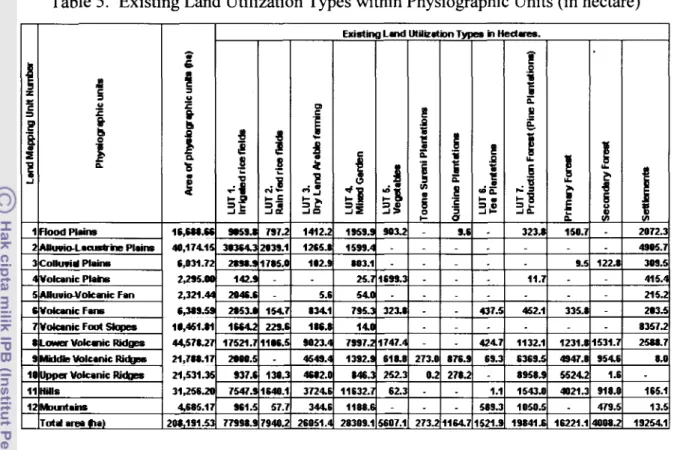

Table 5. Existing Land Utilization Types within ... 40 Physiographic Units (in hectare).

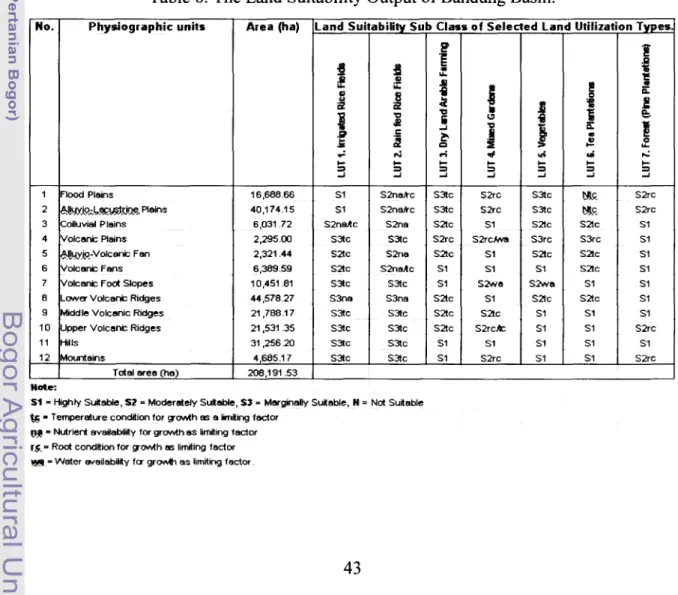

Table 6. The Land Suitability Output of Bandung Basin. ... 42

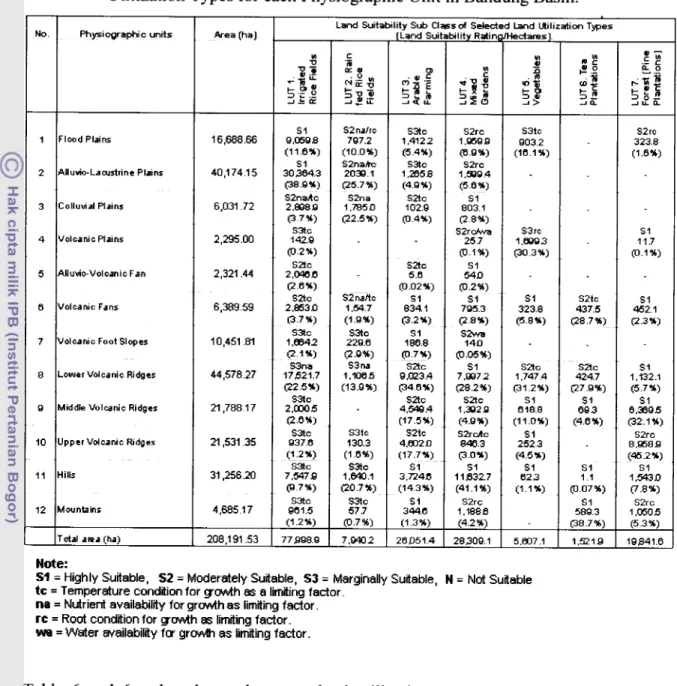

Table 6a. The area (ha) of Land Suitability Output of Selected Land

---

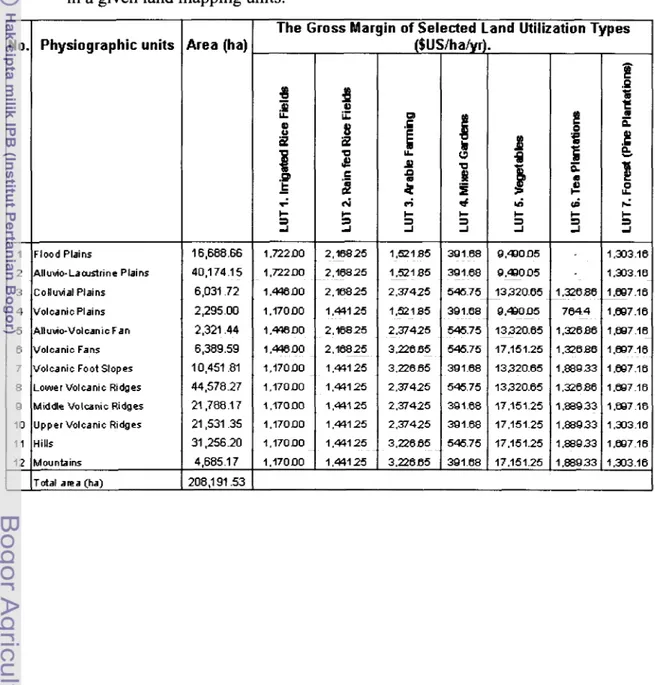

43 Utilization Types for each Physiographic Units in Bandung Basin.Table 7. The BenefitJCost Ratio (BCR) of the Selected Land

---

48 Utilizations Type (LUT) in a given Land Mapping Unit.Table 8. Gross Margin of the Selected Land Utilizations Type (LUT) --- 49 in a given Land Mapping Units.

Table 9. Economic and Physical Suitability of the Selected --- 5 0 Land Utilization Types (LUTs) within the existing area of

LIST OF FIGURES

Contents Page

Figure 1. Study area location. ...

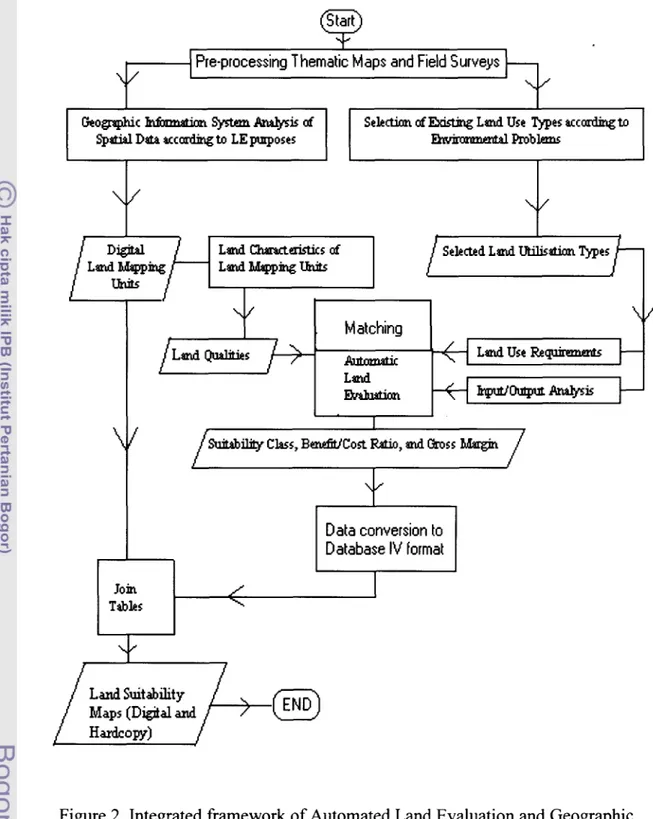

Figure 2. Integrated framework of Automated Land Evaluation and --- Geographic Information Systems for Evaluating Land Suitability.

Figure 3. Illustration on querying the Attributes of Land Mapping ---

Unit using Arc View Geographic Information Systems.

Figure 4. Illustration on determining the Characteristics of Land

---

Mapping Unit for Land Evaluation Purposes.Figure 5. Land Mapping Units of Bandung Basin. ...

Figure 5a: Map of Existing Landuse in Bandung Basin West Java Indonesia. --

Figure 5b. Land Suitability Map of LUT 1 :Irrigated Rice Fields.

---

Figure 5c. Land Suitability Map of LUT 2: Rain Fed Rice Fields ---

followed by corn, peanut & Chinese cabbage.

Figure 5d. Land Suitability Map of LUT 3: Dry Land Arable Farming

---

(Corn, chilly and dry paddy).Figure 5e. Land Suitability Map of LUT 4: Mixed Garden ... (Banana, Bamboo, Jackfruit and Petai).

Figure 5f. Land Suitability Map of LUT 5: Vegetables

...

(Chinese cabbage, carrot, cabbage, tomato, chilly, corn & potatoes).Figure 5g. Land Suitability Map of LUT 6: Tea Estates ...

(Tea and Toona Sureni plantations)

LIST OF APPENDIXES

Appendix 1 : Suitability Classes for Landuse Requirement of Selected Land Utilization Types (LUTs) matching with Land Characteristics.

Appendix 2: Input and output per hectare of existing LUT- 1 (Irrigated rice followed by Kangkung).

Appendix 3: Input and output per hectare of existing LUT- 2 (Rainfed rice field followed by vegetables).

Appendix 4: Input and output per hectare of existing LUT- 3 (Dryland arable farming).

Appendix 5: Input and output per hectare of existing LUT- 4 (Mixed garden).

Appendix 6: Input and output per hectare of existing LUT- 5 (Vegetables).

Appendix 7: Input and output per hectare of existing LUT

-

6 (Tea estate).Appendix 8: Input and output per hectare of existing LUT - 7 (Interculture forest estate -Pine plantations).

Appendix 9: Area of Existing Landuse with Land Suitability Output of Selected Land Utilization Types (LUT) for each Physiographic Unit in Bandung Basin.

Appendix 10: Map of Existing Landuse in Bandung Basin West Java Indonesia.

Appendix 1 1 : Land Suitability Classifications.

Appendix 12: List of Pictures.

I. INTRODUCTION

1. Background.

Land evaluation is concerned with the assessment of land performance when used for

specified purposes. It involves the execution and interpretation of basic surveys of

climate, soils, vegetation and other aspects of land in terms of the requirements of

alternative forms of land use. To be of the value in planning, the range of land uses

considered has to be limited to those, which are relevant within the physical, economic

and social context of the area considered, and the comparisons must incorporate

economic considerations.

Land evaluation supports land use planning by supplying alternatives for land resource

use and providing for each alternative, information on yield and input levels (andfor

benefits and costs), management, needs for infrastructures improvements and effects of

the land uses or land use changes and the planning of interventions in the form of

policies, programmes and projects to implement such land uses or land use changes, are

part of the (land use) planning process. Land evaluation specialists should be involved in

the integration of land evaluation results into this process (Food and Agriculture

Organization, 1976).

Decisions on land use have always been part of the evolution of human society. In the

past, land use changes often came about by gradual evolution, as the result of many

separate decisions taken by individuals. In the more crowded and complex world of the

present, they are frequently brought about by the process of land use planning. Such as

planning takes place in all parts of the world, including both developing and developed

countries. It may be concerned with putting environmental resources to new kinds of

productive use. The need for land use planning is frequently brought about, however, by

changing needs and pressures, involving competing uses for the same land.

Over the past decades, land use in developing countries has been subject to an

livestock products. In many areas, rapid urbanization, mining and deforestation have also

greatly affected patterns of land use.

Projections for the year 2002 and beyond suggest that, due to population increase and

income growth, demand for food and other agricultural products will continue to rise by

over 3% annually (Smith, 1989). In most countries the diet is expected to diversify in

favor of higher value commodities such as horticultural products. This will have

important implications for future land use.

Since the 1960s, growing food demands have been met through substantial increases in

food supply, resulting from both area and per hectare yield increases. The degree to

which it will be possible to meet future needs will depend on the ability to expansion of

arable land is very limited. Moreover, even where agricultural land use could still be

extended, such as in tropical forest areas, this would pose a serious threat to fragile

ecosystem (Pierce et al., 1983).

Efforts to increase agricultural productivity through improved technology, however, have

focused so far nearly exclusively on relatively well-endowed areas, in terms of physical

resources and infrastructure, and on a narrow range of staple cereals. Whiles this so-

called Green Revolution approach has been very successful in terms of output growth, the

effects on equity have been diffuse, depending on the nature of poverty in a given area.

Other factors, e.g., institutional inadequacy, population growth and labor displacing

mechanization, also have influenced equity issues. One firm conclusion seems to be that

farmers in less-endowed areas not suitable for the main crops covered by international

agricultural research centers.

In recent years, sustainability has become a key concept to describe the successful

management of resources for agriculture to satisfy changing human needs while

maintaining or improvement the quality of the environment and conserving natural

developed, there is little doubt that intensification of land use at low external input levels

is hardly ever sustainable.

Today, one is witnessing a situation of changing demands on land use, of increased needs

to deploy efforts in marginal areas and of growing concerns about environmental issues.

Under these condition, designing sustainable land use systems capable of meeting

qualitatively expanding needs of the population in developing countries, present an

enormous challenge to all those concern.

2. Problem Statements

The function of land use planning is to guide decisions on land use in such a way that the

resources of the environment are put to the most beneficial use for man, whilst at the

same time conserving those resources for the future. This planning must be based on an

understanding both the natural environment and of the kinds of land use envisaged. There

have been many example of damage to natural resources and of unsuccessful land use

enterprises through failure to take account of the mutual relationships between land and

the uses to which it is put, such as land use practices that lead to long-term land

degradation. Various methods of land evaluation for agriculture have been well

documented, but there is still a lack of available tools, which combine the method of

spatial database to allow the automation of land evaluation process. It is a function of

land evaluation with computer technology capabilities to bring about such understanding

and to present planners with comparisons of the most promising kinds of land use.

3.

Land Evaluation.

Land evaluation is the process of assessing the suitability of land for alternative uses.

This process includes:

a. Identification, selection and description of land use types relevant to the area under

consideration.

b. Mapping of the different types of land that occur in the area.

c. The assessment of the suitability of the different types of land for the selected land use

Land is an example of a natural resource which, when properly managed, can be used

again (renewable), but of which the total quantity is limited in relation to the demand for

it (scare). Land is not uniform. It consists of unique units with its specific characteristics

and qualities resulting form genesis, location and use. It is possible to grade land units

according to their qualities.

Land can be used for different purposes, of which food production is just one example.

As land can be used in different ways, it is important to select that way which is most

suited for a particular piece of land and which best serves the interests of those concerned

and involved, or at least to avoid unsuitable uses. Different land uses are often in

competition with each other. Furthermore the population of an area consists of different

groups and individuals, each with their own interests. Consequently, there are bound to

be conflicts over the use of land (Marwan et al, 2000).

To feed the world population adequately, as well as to generate growing incomes and

increasing employment opportunities, it is necessary to increase the productivity of land,

however, not at the expense of land as a resource. Land should be conserved for future

generations: land use should be sustainable. In determining the best modes of sustainable

land use, land evaluation plays an important role.

Land use requirements are biophysical conditions that affect yield and yield stability of

the land use type (management requirements), and yield sustainability of the land use

type (conservation requirement). These requirements are expressed in terms of land

qualities (Bouma, 1989).

In context of land evaluation, land includes all biophysical components of the

environment that influence land use, i.e. agro-climate, landform, soil, surface hydrology,

flora and fauna including the more permanent effects of current or past human activities

on these components. Land is described according to its current qualities, or when land

improvements are considered, according to the (predicted) qualities after the

by land characteristics, observable or measurable, biophysical properties of land (e.g.

rainfall regime, slope, soil depth, soil drainage, pH, the occurrence of toxic plant species,

etc).

A requirement (e.g. nutrient availability in the root zone) is a condition necessary or

desirable for the successful and sustained practice of a land use type. On the other hand,

land units have certain qualities (e.g. nutrient supply by the root zone). By comparing the

requirements with the qualities, matching the suitability of the land use types for the land

units is assessed. This assessment involves estimations of the quantity and quality of the

product that can be obtained from each land unit based on the inputs and management as

defined in the description of the land use types. Matching is an iterative process. On the

basis of the comparisons made, it may be decided (1) to adapt the inputs and management

of the selected land use types; or (2) to consider land improvements that alleviate adverse

land qualities and thereby improve the suitability of land for certain land use types.

Fundamental principles in the suitability assessment in land evaluation are as follows:

-the selected land use types must be relevant to nationallregional development

-the objectives as well as to the physical, economic and social context of the area.

-the land use types are specified in terms of socio-economic and technical attributes, and

of requirements.

-the evaluation involves the comparison of two or more land use types.

-land suitability refers to use on a sustained basis.

-the suitability assessment includes a comparison of yield (benefits) and inputs (cost).

4.

Study Objective.

The main objective of this study is to assess the suitability of different types of land, for

selected and specified land use types. The selected land use types include, forestry land

use types in addition to agricultural land use types, particularly when agricultural areas

may not be productive, sustainable or socio-economically relevant. This study attempts to

develop an automated system for carrying out land suitability assessment for selected

land utilization types in Bandung Basin West Java Indonesia.

5.

Land Evaluation and Land Use Planning.

Land evaluation is only part of the process of land use planning. Its precise role varies in

different circumstances. In the present context it is sufficient to represent the land use

planning process by the following generalized sequence: recognition of a need for

change, identification of aims, selection of a preferred use for each type of land, decision

to implement, implementation and monitoring of the operation (Carter, 1988).

Land evaluation plays a major part in stages of the above sequences and contributes

information to the subsequent activities. Thus land evaluation is preceded by the

recognition of the need for some change in the use to which land is put, this may be the

development of new production uses, such as agricultural development schemes or

forestry plantations or the provision of services, such as the designation of a national park

or recreational area (Sys, 1993).

Recognitions of this need are followed by identification of the aims of the proposed

change and formulation of general and specific proposals. The evaluation process itself

includes description of a range of promising kinds of use, and the assessment and

comparison of these with respect to each type of land identified in the area. This leads to

recommendations involving one or a small number of preferred kinds of use. These

recommendations can then be used in making decisions on the preferred kinds of land use

for each distinct part of the area. Later stages will usually involve further detailed

implementation of the development project or other form of change, and monitoring of

the resulting systems (Jensen, 1986).

6.

Principles.

Certain principles are fundamental to the approach and methods employed in land

evaluation. These basic principles are as follows:

a. Land Suitability is assessed and classified with respect to specified kinds of use.

b. Evaluation requires a comparison of the benefits obtained and the inputs needed on

different types of land.

c. A multidisciplinary approach is required.

d. Evaluation is made in terms relevant to the physical, economic and social context of

the area concerned.

e. Suitability refers to use on a sustained basis.

f. Evaluation involves comparison of more than a single kind of use.

7.

The Limitation and Nature of the Land Evaluation.

The range of possible uses of land and purposes of evaluation is so wide that no one

system could hope to take account of them. Besides such obvious contrasts as those of

climate, differences in such matters as the availability and cost of labor, availability of

detail and emphasis in the evaluation of land.

The land evaluation framework is a set of principles and concept, on the basis of which

local, national or regional evaluation systems can be constructed. Thus the framework is

not an evaluation manual; it does not, for example, specifL such matters as limiting slope

angles or soil moisture requirements for particular kinds of land use, since such values

can never have universal applicability.

Instead, the framework sets out a number of principles involved in land evaluation, some

basic concepts, the structure of a suitability classification and the procedures necessary to

The principles and procedures given in the framework can be applied in all parts of the

world. They are relevant both to less developed and developed countries. They can be

applied to areas where development planning is being applied to the more or less

unaltered natural environment; at other to densely populated lands where the main

concern of planning is to reconcile competing demands for land already under various

forms of use. The framework covers all kinds of rural land use; agriculture in its broadest

sense, including forestry, recreation or tourism, and nature conservation.

The framework is not intended for the distinct set of planning procedures involved in

urban land use planning, although some of its principles are applicable in these contexts.

Nor does the framework take account of resources of the seas. Water on and beneath the

surface of land is, however, of relevance in land evaluation.

The framework is mainly for those actively involved in rural land evaluation. Since most

land suitability evaluations are at present carried out for purpose of planning by national

and local government, this is the situation assumed in references to decision-making, but

the evaluation can also be applied to land use planning by firms, farmers or other

individuals.

The evaluation process does not in itself determine the land use changes that are to be

carried out, but provides data on the basis of which such decisions can be taken. To be

effective in this role, the output from an evaluation normally gives information on two or

more potential forms of use for each area of land, including the consequences, beneficial

11. LITERATURE REVIEW

1.

Definitions

Land evaluation can be a key tool for land use planning, either by individual land users

(e.g., farmers), by groups of land users (e.g., cooperatives or villages), or by society as a

whole (e.g., as represented by governments). There is a diverse set of analytical

techniques which may be used to describe land uses, to predict the response of land to

these in both physical and economic terms, and to optimize land use in the face of

multiple objectives and constraints.

When trying to define Land Evaluation, it is important to take into account two important aspects:

The problem:

Inappropriate land use, which leads to inefficient exploitation of natural resources,

destruction of the land resource, poverty and other social problems, and even to the

destruction of civilization. The land is the ultimate source of wealth and the foundation

on which civilization is constructed.

Part of the solution:

Land evaluation leading to rational land use planning and appropriate and sustainable use

of natural and human resources.

Considering these two aspects, land evaluation may be defined as "the process of

assessment of land performance when the land is used for specified purposes"(Food and

Agriculture Organization of the United States, 1985) or as "All methods to explain or

predict the use potential of land"(Van Diepen et al., 1991).

2.The logical basis of land evaluation

Here is the basic logic that makes land evaluation possible and useful:

a. Land varies in its physical and human-geographic properties ('land is not created

b. This variation affects land uses: for each use, there are areas more or less suited to it, in

physical and/or economic terms;

c. The variation is at least in part systematic (with definite and knowable physical

causes);

d. The variation (physical, political, economic and social) can be mapped, i.e., the total

area can be divided into regions with less variability than the entire area;

e. The behavior of the land when subjected to a given use can be predicted with some

degree of certainty, depending on the quality of data on the land resource and the depth

of knowledge of the relation of land-to-land use.

f. Land suitability for the various actual and proposed land uses can be systematically

described and mapped.

Decision makers such as land users, land use planners, and agricultural support services

can use these predictions to guide their decisions.

3.

Land evaluation in the context of land use planning

Land evaluation exists to provide answers to decision makers who in some sense plan the use of the land. This is an outline of rural land use planning to provide a context for the

study of land evaluation. There is a lot more to say about land use planning.

Key point: in any kind of land use planning, the decision maker needs reliable

information about the characteristics of different land areas and their behavior under land

various uses; this is the function of land evaluation (Euroconsult, 1989).

3.1

Planning

Planning is the process of allocating resources, including time, capital, and labor, in the

face of limited resources, in the short, medium or long term, in order to produce

maximum benefits to a defined group. Although individuals plan for the future, by

'planning' in the context of land evaluation we understand some form of collective

activity, where the overall good of a group or society is considered. Rural land use

3.2 Collective vs. individual rights

Planning becomes necessary as soon as organized society emerges and resources are not

limitless. In some societies the planning process is simplified by having a single decision

maker (autocrat) or a small group of decision makers (oligarchs), whereas in societies

where individual rights are maintained there are a large number of decision makers who

can influence a land use plan (Vink, 1975).

In societies where the rights of individuals are accepted, there is a natural tension

between collective planning and the rights of the individual. An example is the

"landowner's rights" movement in the USA, to oppose restrictions on land use. Another

example is the long-running battle between collective and individual use of lands in the

Adirondack Preserve of New York State. "Freedom" is relative and must be negotiated

according to the rules of engagement of a society. The rights of individuals and society

must be balanced. As far as is practical, decision-making should remain with the

individual, as long as society's goals are met (Beek, 1978).

In some situations of collective resource use, the need for collective planning is self-

evident, e.g., development and use of water resources. In others, there is little or no need

for collective planning, e.g., the decision of which crops to grow can generally be left up

to the individual farmer with the 'invisible hand' of the market providing signals to the

farmer via the price mechanism. There are many intermediate cases, especially where

markets are distorted or do not fully account for social values (e.g., environmental risks,

inter-generational equity, non-renewable resources).

3

- 3 .

Planning vs. adaptation

In static or slowly changing social, political, or physical settings, a series of slow,

adaptive changes in land use are sufficient. This has been the case for much of human

history, although there are many examples of complex societies even in prehistory that

were forced to plan in order to survive. However, in the face of rapid change in any of the

must have planned change. The biggest modem-day reasons for planning are the

explosions of population and wealth-expectation (Mahler, 1970).

3.4 Strategic vs. tactical planning

Strategic: medium to long term, involves an examination of goals, can consider fairly

radical changes to current practice. Tactical: short to medium term (usually less than a

year), goals are already set, the aim is to maximize return in some sense within the

context of the goals, can only consider fine-tuning current practice. Land evaluation is

fundamentally aimed at supporting strategic planning. Short-term or tactical plans (e.g.,

'When should I cut hay this year?') can be assisted by decision-support systems.

3.5

Rural land use planning?

3.5.1 On private land

Rural land use planning is needed to provide maximum economic benefit to the

individual landowner or operator (e.g. farm planning), as well as to prevent or solve

conflicts between individuals and other individuals or with the needs and values of

society as a whole. It is not practical to allow landowners to do whatever they want with

their land, for several reasons:

a. possible direct and immediate effects on other land owners or resource users; the

classic example is diversion or discharge or waters into a stream that is then used by

others,

b. possible indirect andlor delayed effects on other land owners or resource users; a good

example is aquifer depletion following excessive water use,

c. possible direct and immediate effects on the resource base, e.g. water pollution,

d. possible indirect andlor delayed effects on the resource base, e.g. climate change,

e. society may have a collective interest (valid or not) in discouraging certain land uses

and promoting others. e.g., Japan's desire to be self-sufficient in rice and the US in

sugar.

f. Different land uses have different infrastructure requirements (roads, schools), which

the state may or may not be prepared to meet. e.g., an industrial park will certainly

3.5.2 On state-owned land

In this case, the state must plan as would a landowner (e.g., 'management plan' for a

national forest) but almost always in the face of multiple demands on thi land and

conflicting values (Young, 1973).

In addition, the state is usually required by law or policy to take a long-term, at least

partially non-market view of its land. This is because the state represents the interests of

all of society. Classic example: logging vs. wilderness in national forests: various sectors

of society have different short- and long-term interests.

3.6. Proscriptive vs. prescriptive planning

Rural planning can be quite lax, generally orienting but not controlling (neoliberal) or

quite strict (static).

Planning activities are fundamentally of three kinds:

(I) proscriptive;

(2) indirectly prescriptive and

(3) directly prescriptive.

In practice these may be combined, e.g. a government may create an agricultural district

by zoning, favor it with tax incentives, and also build rural schools and community

centers.

3.6.1. Proscriptive land use planning ('zoning').

The 'decision maker' has the power to prevent or regulate, but will not actually expend

any energy or resources, other than that required by the police power. General terms:

zoning; 'passive' or 'normative' planning. The state has police power over land use,

backed up by the judiciary. In the final analysis, proscriptive planning depends on the

police power of the state to prevent uses that are not in its interest, although without a

consensus with the affected parties, and a judiciary system that is perceived as

Examples: (1) Wetland protection in the USA and Farmland preservation vs.

Development.

3.6.2. Indirectly prescriptive land use planning

The decision maker has power to perform indirect actions which cost it money and which

affect the land use indirectly, by favoring certain kinds of uses. These are also called

incentives to these land uses (Davidson, 1992).

Example: preferential taxation for agricultural districts (reduced revenue).

Example: support prices for agricultural commodities (increased expenditure).

Example: tariff and non-tariff barriers to imports (e.g., US sugar quotas, EC tariff on

Latin American bananas).

3.6.3. Directly prescriptive land use planning

The decision maker has the power to perform direct actions, which affect the land use.

These are of two types:

(1) Implement the land use

The landowner or operator has this power. The plans are of two basic types: a

management plan and a strategic plan.

(2) Directly support the land use

Landowner with actions that facilitate the use or remove a cost from the land users

Example: infrastructure improvement: roads, irrigation systems

3.7. Legal and institutional structure of land use planning.

This varies greatly among countries or even provinces and states. Here we enter into the

realm of political theory as well as sociology. The basic question is, what is the structure

of political society, i.e., how are decisions made?, and how are rights to make decisions

3.7.1. What is government?

One view: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that

they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are

Life, Liberty and pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are

instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed."

(Siderius, 1986).

In this view, the government and its laws codify the more-or-less common opinion of the

people as to fair practice, arrived at after some process of consensus-building (various

forms of 'democracy' within a defined structure for debate and decision-making). There

are mechanisms by which all affected parties can make their opinions known (e.g.,

legislatures) and by which they can decide among competing claims according to the law

(i.e., a judiciary system). The government exists to improve the welfare of the people and

therefore is tolerated by them.

Another view: Government is the institution which holds at least some actual power over

a territory and can convince, usually by the use or threat of force of arms, other political

entities that it must be respected when dealing with that territory. This is the view of the

United Nations. Democracy in any sense of the word is irrelevant unless it suits the needs

of other powers (e.g. USA attitude towards CubdCastro vs. ChileIPinochet).

In fact many de jure and de facto governments do not function with the 'consent' of large numbers of the governed, but instead represent certain classes, interests, ethnic groups,

families, or even temporary assemblages of profiteers. The reactions of the

unrepresentative governed range from passive acceptance to open rebellion. In these

hands the law becomes an instrument of oppression and control rather than expressing a

consensus. The government exists to improve the welfare of the governing group and to

suppress any opposition. Many governments combine both types of behavior.

In a planning context, these differences have great practical implications. The more open

process, the more likely is a successful long-term plan. Coercive governments with

centralized decision making may be able to produce and carry out plans more rapidly, but

in the long term they will be less successful (e.g., former Soviet Union).

3.7.2 Legal basis of zoning

Government gives permissions (implicit, from a zoning map, or explicit, by variances or

permits); may be centralized or decentralized (local government). Advantages of

centralization: consistent standards, less chance of petty corruption. Advantages of

decentralization: adaptable to local needs, less chance of large-scale corruption and

influence peddling. The appropriate scale is where participatory decision-making and

accountability is greatest (Fresco, 1999).

3.7.3. Legal basis of direct planning.

In many developing countries, social-welfare agencies provide important rural

infrastructure called Integrated Rural Development project of a selected area.

-By individuals or partnerships (e.g., farmers), from their rights of use over the land.

-By collectives (e.g., irrigation districts), from their legal mandates as expressed in their

articles of incorporation, supported by law or precedent.

-By government agencies formed for the explicit purpose of managing resources (US

Forest Service), or providing assistance to individual land owners (USDA Soil

Conservation Service), by their legal mandate.

-By governmental agencies that provide infrastructure (Departments of Transportation),

again within their legal mandate.

3.8. A

transparent and rational process is desirable

Almost always the various individuals and interest groups will be in conflict over any

zoning plan, management plan, tariff policy, taxation plan, or infrastructure investment.

Some parties (all?) will feel that the plan is against their interest.

In a transparent (or, open) process, the planner adjusts the plan according to the openly

and groups, so that the greatest number of parties is the most satisfied possible.

Furthermore, all affected parties can see exactly how the plan was developed and how

disputes were resolved. This has two great benefits: (I) the plan is likely to be'better and

'fairer' at least in the aggregate; (2) all parties are more likely to support the final plan.

A rational process is reproducible by following a definite methodology. All the

assumptions and any subjective judgments are clearly expressed and open to challenge.

Even though preferences may not be 'rational' (in the sense of maximizing benefits) or

even highly subjective, they must be quantified as far as possible (Rossiter, 1994).

In many countries there is a lack of transparency in many activities of the government,

which brings with it a loss of confidence in government, political and social instability,

and a loss of respect for and support of the management plan or other planning action. Of

course, there is usually a reason for lack of transparency: the planner or decision maker

has something to hide.

The land evaluator can contribute greatly to making the planning process transparent and

rational. The rational part comes from the use of sound analytical techniques, and the

transparent part comes from the presentation of all assumptions, data, and methods used

in the analysis. For example, it is not acceptable to present a single 'final plan' without

showing source documents, reporting on key assumptions, and explaining how the plan

was derived (Yeh et al., 1998).

4. The aims of land evaluation for development purpose.

Evaluation takes into consideration the economics of the proposed enterprises, the social

consequences for the people of the area and the country concerned, and the

consequences, beneficial or adverse effect, for the environment. Thus land evaluation

should answer the following questions:

a. How is the land currently managed, and what will happen if present practices remain

unchained?

c. What other uses of land are physically possible and economically and socially

relevant?

d. Which of these uses offer possibilities of sustained production or other benefits?

e. What adverse effects, physical, economic or social, are associated with each use?

f. What recurrent inputs are necessary to bring about the desired production and minimize

the adverse effects?

g. What are the benefits of each form of use?

If the introduction of a new use involves significant change in the land itself, as for

example in irrigation schemes, then the following additional question should be

answered:

h. What changes in the condition of the land are feasible and necessary, and how can they

be brought about?

i. What non-recurrent inputs are necessary to implement these changes?

4.1. Levels of intensity and approaches.

Certain groups of activities are common to all types of land evaluation. In all cases

evaluation commences with initial consultations, concerned with the objectives of the

evaluation, assumptions and constraints and the methods to be followed. Details of

subsequent activities and the sequence, in which they are carried out, vary with

circumstances (Vincent, 1997). These circumstances include the level of intensity of the

survey and which of two overall approaches is followed.

4.1.1 Levels of intensity

Three levels of intensity may be distinguished: reconnaissance, semi-detailed and

detailed. These are normally reflected in the scales of resulting maps. Reconnaissance

surveys are concern with broad inventory of resources and development possibilities at

regional and national scales. Economic analysis is only in very general terns, and land

evaluation is qualitative. The results contribute to national plans, permitting the selection

Surveys at semi-detailed, or intermediate, level are concerned with more specific aims

such as feasibility studies of development projects. The work may include farm surveys;

economic analysis is considerably more important, and land evaluation 'is usually

quantitative. This level provides information for decisions on the selection of projects, or

whether a particular development or other change is to go ahead (Olson, 1974).

The detailed level covers surveys for actual planning and design, or farm planning and

advice, often carried out after the decision to implement has been made.

4.1.2 Two-stage and parallel approaches to land evaluation.

The relationship of resources surveys and economic and social analysis, and the manner,

in which the kinds of land use are formulated, depend on which of the following

approaches to land evaluation is adopted.

A two-stage approach in which the first stage is mainly concerned with qualitative land

evaluation, later followed by a second consisting of economic and social analysis. A

parallel approach in which analysis of the relationships between land and land use

proceeds concurrently with economic and social analysis.

The two-stage approach is often used in resource inventories for broad planning purpose

and in studies for the assessment of biological productive potential. The land suitability

classifications in the first stage are based the beginning of the survey, e.g, arable

cropping, dairy farming, maize, tomatoes. The contribution of economic and social

analysis to the first stage has been completed and its result presented in map and report

form, these results may then be subjects to the second stage, that of economic and social

analysis, either immediately or after an interval of time.

In the parallel approach the economic and social analysis of the kind of land use proceeds

simultaneously with the survey and assessment of physical factors. The kind of use to

which the evaluation refers is usually modified in the course of study. In the case of

rotations, estimate of the inputs of capital and labors, and determination of optimal farm

size. Similarly, in forestry it may include, for example, selection of tree species dates of

thinning and felling and required protective measures. This procedure is mosily favored

for specific proposals in connection with development projects and at semi-detailed and

detailed levels of intensity.

The parallel approach is expected to gives more precise results in a shorter period of time.

It offers a better chance of concentrating survey and data-collection activities on

producing information needed for the evaluation (Young, 1973). However, the two-stage

approach appears more straightforward, possessing a clear-cut sequence of activities. The

physical resource surveys precede economic and social analysis, without overlap, hence

permitting a more flexible timing of activities and of staff recruitment. The two-stage

approach is used as a background in the subsequent text except where otherwise stated.

5.0.

Automated Land Evaluation System.

The Automated Land Evaluation System is a computer program that allows land

evaluators to build expert systems to evaluate land according to the method presented in

the Food and Agriculture Organization "Framework for Land Evaluation". It is intended

for use in project or regional scale land evaluation. The entities evaluated by Automated

Land Evaluation System are map units, which may be defined either broadly or narrowly

as in detailed resource surveys and farm scale planning. Since each model is built by a

different evaluator to satisfy local needs, there is no fixed list of land use requirements by

which land uses are evaluated, and no fixed list of land characteristics from which land

qualities are inferred. Instead, these list are determined by the evaluator to suit condition

and objectives (Rossiter, 1994).

Automated Land Evaluation System runs on the IBM PC microcomputer and its

successors and on "PC-compatible" machines, under the PC-DOS operating system,

version 2.3 or later. It requires at least 384 Kb of primary (RAM) memory (preferably

640Kb) and minimum of 3.5 Mb of space on a hard disk. Either a color or monochrome

Workgroups, Windows 95 and PC-DOS or MS-DOS. Automated land evaluation system

is written in MUMPS programming language and uses the Data Tree MUMPS language

and database system(Rossiter, 1994).

The aim of automated land evaluation system is to allow land evaluators to collate,

systematize and interpret this diverse information using the basic principles of the FA07s

"Framework for Land Evaluation" and to present the interpreted information in a form

that is useful to land use planners. The program is designed to allow contributions from

all relevant sources of knowledge. A further objective is to use the large quantity of

information that has been recorded to date in soil surveys and other land resource

inventories, much of which is sitting unused on office shelves. There are a variety of

reasons for this disuse, primary of which is that the surveys are not interpreted for various

land uses and secondly that surveys have widely different definitions of map units and

land characteristics. So a major design objective of automated land evaluation system is

to allow the use of land data in almost any format, as well as easy interchange of

111.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Land evaluation involves the analysis of biophysical and socio-economic data. The land

evaluation methodology thus consists of integrating a number of concurrent and

sequential activities, which include the collection, analysis, and integration of different

data sets.

After planning the evaluation itself, it includes the following steps:

a. Selection and description of land use types, which are relevant to policy objectives, the

development objectives as formulated by planners and to the overall socio-economic,

land use and ago-ecological conditions in the area.

b. Determination of the land use requirements of each of the selected land use types.

c. Delineation of land (mapping) units based on the results of land resource surveys

(climate, landforms, soils, land use, and vegetation). Each of these land units has a

number of characteristics such as slope, rainfall, soil depth, drainage, vegetation cover,

etc., in which it differs from neighboring land units.

d. Translation of the characteristics of each land units into land qualities such as the

availability of water and nutrients, which have a direct impact on the performance of

the selected land use types.

e. A 'matching' process in which the requirements of the land use types are compared

with the qualities of each of the land units. This leads to suitability classifications of the

land units in physical terms, separately for each of the land use types considered.

Suitability classes express the relative fitness of a certain land-mapping unit for a

selected land use type. Suitability classes may refer to current land conditions, or, when

land improvements are considered in the evaluation, to suitabilities after the

implementation of these improvements.

f. An analysis of possible environmental impacts of land use changes that might be

implemented on the basis of the results of the land evaluation and depending on the

The main types of information on land resources required for land evaluations for

agricultural purposes concern agro-climate, surface and/or groundwater resources,

landforms, soils, and present land cover and land use. In land evaluations for forestry,

extensive grazing and nature conservation, a forest inventory and vegetation survey may

be needed in addition (Nossin, et al., 1996).

Land evaluation is thus essentially based on a comparison of land resource data with land

uses and the ecological, management and conservation requirements of these land uses. It

is ideally carried out by a team, which includes one or more land resource scientists,

agronomists, (socio-) economists, rangeland specialist, forestry specialist, etc. The team

composition is determined by the objectives of the evaluation and by the land uses

considered to be relevant for the area (Centre for Soil Research and Agroclimate, 1993).

1. Time and location of the study area.

This study has been conducted from February until July 2002 at Bandung Basin of West

Java Indonesia. The catchment area includes the Saguling Reservoir with an area of

approximately 2,283 square krn, geographically located between latitude 6" 4' S and 7"

10' S, and longitude 107" 15' E and 107" 45' E, (see Figure 1).

The Saguling reservoir was built in 1985, and is one of four dams in the Upper Citarum

watershed, with a capacity to generate approximately 700 megawatts of energy. Although

the economic lifetime of the reservoir was estimated to be 5 1 years, the high volume of

sedimentation due to forest clearance, soil erosion and inappropriate land use and

management practices has reduced this estimation to around 45.4 years (Japan

2. Data Sources.

The principle supporting data for this study are the following spatial and non-spatial data

available from Center for Soil and Agro-climate Research (Puslittanak) and National

Mapping and Survey Organization (Bakosurtanal): (a) Spatial data consisting of thematic

maps at scale 1: 100,000 (i.e., topography, geology, soil, slope, elevation and existing

land use), (b) climatic data, and (c) non-spatial data consisting of socioeconomic data

(i.e., agricultural productions, agricultural price lists, local population conditions). Data

were also collected by ground fieldwork checking and observations in the study area.

3. Hardware and Software.

Supporting Hardware and Software required are as follows:

a. Hardware

Personal Computer Pentium I1 having 64.0 MB RAM and 6 GB hard disk

Digitizer

Plotter

Color Printer

Global Positioning System (GPS).

b. Software

ArcInfo 3.5

ArcView 3.1

ALES Version 4.65d

4. Methods

The automated land evaluation system (ALES), ArcInfo, and ArcView were used to build

the land suitability models. A loose coupling strategy as illustrated in Figure 2 was