Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:31

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Hot or Not: An Analysis of Online

Professor-Shopping Behavior of Business Students

Tarique M. Hossain

To cite this article: Tarique M. Hossain (2009) Hot or Not: An Analysis of Online Professor-Shopping Behavior of Business Students, Journal of Education for Business, 85:3, 165-171, DOI: 10.1080/08832320903252439

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320903252439

Published online: 08 Jul 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 55

View related articles

CopyrightC Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0883-2323

DOI: 10.1080/08832320903252439

Hot or Not: An Analysis of Online

Professor-Shopping Behavior of Business Students

Tarique M. Hossain

California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, California, USA

With the proliferation of Web sites that allow students to praise or disparage their instructors depending on their whims, instructors across the country essentially are becoming subjects of comparison shopping by prospective students. Using a sample survey of 258 students majoring in business at a public university on the west coast of the United States, the author investigated the extent of instructor-shopping behavior via browsing and posting comments on the Internet as well as the students’ motivations behind such activities. An analysis of data suggests that nearly one third of students engage in online information sharing before signing up with a particular professor and that factors related to grade expectation affect the propensity to shop on the internet.

Keywords: Logistic regression, Professor-student relationship, Student behavior, Students’ evaluation of teaching

Although academic researchers debate whether students should be treated as customers or not (e.g., Franz, 1998; Sirvanci, 1996), students are becoming more inclined to view their professors as service providers. This trend is evidenced by the proliferation of Web sites such as Ratemyprofes-sors.com, Pick-a-prof.com, and Goodbadtenured.com. These venues serve as online public forums where students can nu-merically rate and post mostly unfiltered open-ended com-ments about their professors—thanks to the convenience and anonymity these sites provide them. Although the growing popularity of these Web sites among students can be at-tributed to students’ desire to know more about classes and the instructors who taught them (Kindred & Mohammed, 2005), little is known about the attitudes and profiles of stu-dents who engage in such consumer-like shopping behavior. Students’ evaluation of professors via third-party sources have received relatively little attention in academic literature in comparison with the amount of articles written on stu-dents’ evaluation of teaching administered by the universi-ties. The Internet has altered and, to some extent, augmented how students rate their professors and how their peers join them in adding comments and browsing reviews posted by others as an aid in selecting professors for the courses they

Correspondence should be addressed to Tarique M. Hossain, California Sate Polytechnic University–Pomona, International Business & Market-ing, 3801 West Temple Ave, Pomona, CA 91768, USA. E-mail: tmhos-sain@csupomona.edu

might consider taking. Clearly, there is an expected informa-tional advantage to be gained from engaging in peer-to-peer information sharing about professors. Most schools collect the students’ evaluation scores, but these data are not avail-able to prospective students in a timely manner—if at all. The Internet sites thrive on this apparent scarcity or inconve-nience associated with using and accessing information from university-administered evaluation surveys.

Some professors are not amused to see themselves critiqued by what they view as flippant and often taliatory students (Gigerich, 2003). Some professors re-portedly have offered rebuttal to their critics at Rate-myprofessors.com on the Web sites of MTV-U, who ac-quired the professor-rating site. Faculty members may be inclined to dismiss the Internet reviews as frivolous and biased, but these online ratings are increasingly fea-tured in newspaper articles (Gigerich) and, in some in-stances, even included as a factor in ratings of colleges. For example, Forbes magazine recently featured a rank-ing of U.S. colleges in which the source used students’ ratings at Ratemyprofessors.com as one of the criteria (Vedder, 2008). Further, there is always the chance that fas-tidious college administrators might investigate into such rat-ing sites to get yet another data point on a professor durrat-ing the retention and tenure decisions. Thus, as long as students continue to rate their instructors on the Web, this new pub-lic media of students’ evaluation of teaching raises impor-tant and interesting questions for researchers. What are the

166 T. M. HOSSAIN

profiles of students who rate professors on these sites? Do the comments come from mostly bitter students who are fo-cused more on boosting grades by cherry-picking professors and caring less about learning and scholarship? What are the attitudes of the students who browse and shop for profes-sors? Further, are the students who choose to air their views on the Internet different, in important ways, from the pop-ulation they come from? This latter question poses the po-tential problem of self-selection that can misrepresent the opinions of the student population as a whole—whether they participate in online information sharing or not. In the present article, I attempt to provide descriptive analy-ses of students behavior regarding shopping for their de-sired professor as it relates to reading and posting reviews on public Web sites. I also conduct a predictive analy-sis of students’ propensity to shop as a function of their work ethic, grade dissatisfaction, grade focus, and feeling of entitlement.

BACKGROUND

Students’ evaluation of teaching has generated a lot of aca-demic research across many disciplines. Generally, this body of literature appears to address a central theme of poten-tial bias and shortcomings of the students’ evaluation as a measure of instructors’ teaching effectiveness (Yunker & Yunker, 2003). A majority of the articles have focused on var-ious aspects of students’ evaluation of teaching ranging from students’ perception of the evaluation process and teaching (Marsh, 1984, 1987; Marsch & Roche, 1993; Whitworth, Randall, & Price, 2002), experience of instructors and class size (McPherson, 2006), instructors’ personality (Clayson & Sheffet, 2006), the relationship between students’ evalu-ations of teaching and faculty evaluevalu-ations (Read, Rama, & Raghunandan, 2001), to students’ actual or expected grades (Clayson, Frost, & Sheffet, 2006). The results produced in these articles conclude that factors such as class size, stu-dents’ perception of the evaluation process, and measures of instructors’ personality all significantly affect students’ eval-uation of teaching. The effect of grades, actual or expected, turns out to be the most controversial. For example, accord-ing to Aleamoni (1999), some 24 studies have reported no relationship (e.g., Aleamoni & Hexner, 1980; Baird, 1987), but 37 articles have suggested significant positive relation-ships (e.g., Blunt, 1991; Wilson, 1998) between grades and students’ evaluation. As the focus of this article is students’ Internet-based evaluation and shopping behavior, instead of the traditional students’ evaluation done by administrators, I turn to review some papers that have dealt with the former kind of evaluation.

Although the practice of posting online reviews of pro-fessors by students is not entirely new, academic research on this topic is very limited and seems to be appearing only recently. The existing literature dealing with online professor reviews tends to focus on the bias in students’

rating and inconsistencies in the metric measurements as re-flected in secondary data collected from Web sites such as Ratemyprofessors.com (e.g., Felton, Mitchell, & Stinson, 2004; Lawson & Stephenson, 2005). In particular, Lawson and Stephenson found that students rate professors higher when they are perceived as being easy. In addition, Felton et al. used secondary data of rating categories from Ratemypro-fessors.com. The five numeric rating categories are easiness (how easy are the classes this professor teaches?), helpful-ness (is the teacher approachable and nice?), clarity (is he or she clear in presentation?), overall quality (average of a teacher’s helpfulness and clarity ratings), and hotness total. Felton et al. found the correlation between overall quality and easiness to be.61. Based on a regression analysis, Fel-ton et al. concluded that because students’ rating of overall quality is susceptible to bias due to the perceived easiness of the instructors, these ratings and, by extension, the tradi-tional student evaluation administered by universities need to be viewed with suspicion. In other articles, also utiliz-ing publicly available online ratutiliz-ing data, researchers have investigated whether ratings were biased by perceptions of the hotness of instructors indicated by the raters (Riniolo, Johnson, Sherman, & Misso, 2006). In sum, these studies have documented the presence of bias in rating of quality of instructors either by the perceptions of easiness or by percep-tions of hotness. However, it is important to question whether this bias could originate from self-selection of sampling bias (i.e., if students who choose to post ratings on the Web sites are systematically different from those who choose not to post—an issue I empirically test in this article).

Although some research has been emerging in the area of online professor ratings, most studies have fo-cused on the product (i.e., the ratings themselves), typi-cally establishing the inherent flaws in the ratings. This trend of research leaves a substantial gap in literature in terms of understanding the students’ own views about these Web-based ratings. Judging by the enormous cov-erage of some rating Web sites, their growing popularity is obvious. For example, Ratemyprofessors.com (2008) re-ports “over 6,000 schools, 1 million professors, 6 million opinions.” The corresponding figures in 2004 were 4,200 schools, 450,000 professors, and 2.5 million ratings (cf. Kindred & Mohammed, 2004). With one notable exception, Kindred and Mohammed’s study, research on the profiles of students who appear to be consumers and producers of in-formation generated in these sites is conspicuously absent in academic literature. Kindred and Mohammed used qualita-tive data such as focus-group interviews and content anal-ysis of verbal comments posted on Ratemyprofessors.com to investigate the issue of motivations which underlie the popularity of information sharing in such sites. They found that despite the subject students’ understanding of the limita-tions of the ratings and the comments posted on Ratemypro-fessors.com, the convenience of browsing information in a world with few other viable sources of such information jus-tifies their use of the Web site. In other words, they seem

to use the Web site subject to the individual students’ inter-pretation of what the rating or comments might be saying between the lines. In the content analysis part of their study, Kindred and Mohammed coded several hundred open-ended comments to derive categories (e.g., age, gender, intelligence, competence, personality) and report that the most frequent concern was instructor competence, followed by personal-ity. Although a well-executed study representing interesting findings on students who use the most popular rating site, Kindred and Mohammed’s findings from focus groups were less amenable to statistical inference. In the present article, I approach similar issues using a sample survey and attempt to provide descriptive as well as predictive analyses of students’ shopping behavior for a professor.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

In the present study, I aimed to investigate the extent of students’ shopping behavior via information gathering and posting ratings on the third-party Web sites and students’ motivation for engaging in shopping behavior. Another ob-jective was to find out differences, if any, among the students who post and those who do not post reviews. In addition, I looked into the attitude of students toward grading, learn-ing, and the feeling of entitlement in an effort to explain the professor-shopping behavior. The effect of attitudes on behavioral intention has been well documented in market-ing literature (Allen, Machleit, & Kleine, 1992; Dabholkar, 1994). Attitudes have been studied in the marketing educa-tion context as well and found to be significant in influencing student satisfaction (Curran & Rosen, 2006). When it comes to attitudes of students in the context of learning, the most plausible constructs are their attitude toward work ethics, priority of high grade over learning, and entitlement. Enti-tlement is frequently cited by researchers as a characteristic of Generation Y learners (Windham, 2005).Generation Y, also known as the millennial generation as well as the net generation, is defined as to include those individuals born between 1982–2002 (McGlyn, 2008) and they are about 115 million strong (Akande, 2008). College campuses are expe-riencing the first wave of these learners, popularly perceived as uniquely different from their boomer and Generation X teachers. Researchers typically characterize Generation Y individuals as digital natives, always connected, addicted to multitasking, and possessing a consumerism attitude toward learning (McGlyn).

Based on the preceding discussion, in the present study I posed the following research questions:

Research Question 1: What is the extent of professor shop-ping behavior among business students?

Research Question 2: Do the attitudes of students explain

their professor shopping behavior?

Research Question 3:Do the attributes students look for in

a professor differ between those who post reviews on public Web sites and those who do not?

METHODOLOGY AND DATA

An anonymous paper-and-pencil survey of a convenience sample of 258 students from a business school at a public uni-versity on the west coast of the United States was conducted to collect data. The survey was approved under the exempt category by the institutional review board at the institution. Questions on the survey included demographic questions, de-scriptive questions, such as if the student shops for professors and how they do that, and what attributes the student looks for in a professor. Further, an attitudinal battery consisting of 12 items using a 4-point Likert-type scale was also included (4=Strongly Agree, 3=Agree, 2=Disagree, 1=Strongly Disagree). Paper surveys were distributed in six classes at various levels (upper and lower) of undergraduate business classes during the summer of 2007. Surveys were adminis-tered in class by students who received introduction to human subjects 101 training. After allowing for missing responses, 239 usable records were included in analyses. In the present study, I used the following variables and latent constructs:

1. Shopping behavior: a self-reported measure of whether students engaged in checking out professors before taking classes with them. Among the response options provided were from friends, academic advisors, or In-ternet sites (un-aided response). Based on the multiple category answers, a dummy variable was created (1= the respondent used Internet as a source of shopping information, 0=other).

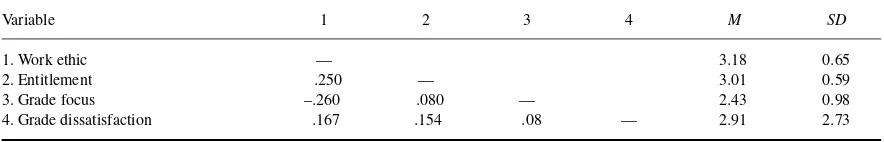

2. Attitudinal categories: An exploratory factor analysis (Table 1) was conducted to derive constructs related to willingness to expend effort for grades (work ethic), feeling of entitlement to better grade (entitlement), per-ceived priority of grades over learning (grade focus), and perceived unfairness in grades received (grade dis-satisfaction). Minimum eigenvalue criteria established four factors. On removing items with poor factor load-ings, summated scales were created using the averages of the ratings for items in each category (Table 2). 3. A comparative rating scale that asked students to

dis-tribute 100 points between the categories of atdis-tributes to look for in a professor, such as easy grading, per-sonality, knowledge, challenge level, teaching clarity, entertainment factor, and appearance.

ANALYSIS

Extent of Professor-Shopping

A frequency tabulation of self-reported shopping behavior indicated that about 29% of students in the sample engaged in shopping for professors by browsing Internet sites. Another 26% of the students sampled did so by asking fellow students about a course and professors who taught it. However, the focus of the present study was students’ shopping behavior using information on the Internet. The students engaging in

168 T. M. HOSSAIN

TABLE 1

Constructs of Students’ Attitudes (N=239)

Item Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3 Factor 4

Work ethic

Hard work in school pays good grades. .825 .080 –.085 –.060 When my GPA falls, I try to recover by studying harder. .757 .205 .000 .017

Good grades need to be earned. .703 .096 .092 .350

Entitlement

Students have a right to better grades. .229 .716 –.114 .069 Choosing the right professor is key to good grades. .033 .689 .350 –.265 Extra credits go a long way in stimulating learning. .270 .672 –.017 –.345 Grade focus

Grades are more important than learning. –.184 –.035 .857 .176 Grade dissatisfaction

The grades I have received so far underestimate my learning. .051 .096 .127 .811

Note.Bold face indicates factor loadings. Items with loadings less than .6 were excluded. Cronbach’s alpha for Factor 1 was .791. Cronbach’s alpha for Factor 2 was .541.

shopping (29%) included students who browse but do not post comments in public Web sites. Because this is the first of its kind of study to investigate this incidence of shopping, it is difficult to judge whether the numbers found in this study are too high or too low. Judging by the fact that it is possible to find millions of postings that rate thousands of professors in Web sites such as Ratemyprofessors.com, a 29% browsing rate seems credible.

Among the students who shop for professors on the In-ternet, 65% have posted at least one comment at same point. That leaves about 35% of the shoppers who indicated they had never posted any comments about their professors on the Internet—they had only browsed ratings and comments on the Web sites. The high percentage of shoppers who had posted reviews while shopping indicates some kind of reci-procity and sense of belonging to a community on the stu-dents’ part in keeping the Web sites alive and well. Interest-ingly, students believe—and rightly so—that other students read the posts, and that motivates them to post (Kindred & Mohammed, 2004). Still, it is possible that the ones who do not add their own comments may refrain from posting, perhaps because postings are triggered by either too good or too bad an experience with an instructor (Kindred & Mohammed).

Explaining Shopping Behavior by Attitudes

I used a logistic regression model with three constructs of attitudes: work ethic, entitlement, grade focus (over learn-ing). The results presented in Table 3 suggest that a higher agreement to work-ethic-related attitudinal statements leads to a lower odds of shopping behavior. The model displays good explanatory power on all three criteria—likelihood ra-tio, Wald, and score. Three of the four explanatory constructs were significant at 5% level of significance. Although the sign of the coefficients turned out as expected, grade focus (grade more important than learning) showed up as not sta-tistically significant. This lack of significance runs counter to the expectation that higher importance of grade over learning would make students more likely to engage in shopping for (easier) professors. One possible explanation for this could be that the item itself was so sensitive that respondents might have given the socially desired response that learning is more important than mere grades. Alternatively, it is possible that students shop regardless of their philosophical belief that grades are more important than learning.

Moving to the next factor, the results suggest that a higher perceived feeling of entitlement makes a student more prone to shop for professors. It is interesting that a higher self-perception of work ethic lowered students’ tendency to shop

TABLE 2

Correlation Matrix of Attitudinal Constructs (Average Summated Ratings of Items Within a Factor;N=239)

Variable 1 2 3 4 M SD

1. Work ethic — 3.18 0.65

2. Entitlement .250 — 3.01 0.59

3. Grade focus –.260 .080 — 2.43 0.98

4. Grade dissatisfaction .167 .154 .08 — 2.91 2.73

TABLE 3

Logistic Regression Results (N=239)

Variable B SE B Waldχ2(1, 239) p

Intercept 3.54 1.1558 9.39 .002

Work ethic –.66 .2936 5.03 .025

Entitlement .81 .2797 8.30 .004

Grade focus .20 .1658 1.54 .214

Grade dissatisfaction .48 .1857 6.81 .009

Note.Likelihood ratioχ2(4,N=239)=22.34,p=.0002; Scoreχ2(4,N=239)=15.45,p=.0039; Waldχ2(4,N =239)=17.76,p=.0014.

around for professors. That is, if students believes that they need to do the homework to earn a better grade, they may have less faith in a possible gain from spending time read-ing what other people think of a particular professor. Grade dissatisfaction plays a significant role in raising the odds of engaging in checking out professors’ ratings before commit-ting to a class. The significance of grade dissatisfaction as a driver of shopping activity confirms the notion that stu-dents expect some informational advantage from their time spent on professor rating sites, primarily in terms of a better expected grade.

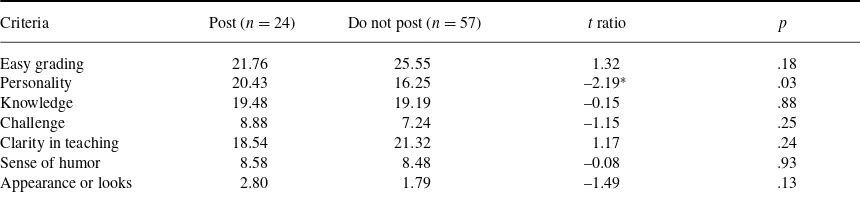

Are Students Who Post Reviews Different From Those Who Do Not?

A comparative rating scale depicting relative importance of attributes students look for in a professor provided insight into students’ priorities. As reported in Table 4, a t-test comparison of means between those students who never posted online comments versus those who posted at least once provided evidence as to whether a self-selection is at work among the students who post online ratings of profes-sors. Results from an independent-samplesttest suggest that these two groups of students are not statistically different from each other on most of the criteria, except personality of the professor. That is, on average, the posting group indi-cated over four-percentage points more weight on personality (their second highest priority) than their nonposting

counter-part (third highest priority). The former group also displayed higher importance of the instructor’s appearance but the dif-ference failed the statistical significance test. Thus, I found only partial evidence of self-selection in online raters, in that they placed more importance on personality than did their browse-only peers.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This article provides a first-of-its-kind analysis of information-searching behavior of college students based on survey data collected at a public university. Generally, the re-sults presented conformed to a number of findings reported in earlier studies, namely that student evaluation of teaching is tainted by a number of factors that are beyond the control of the instructor. Prior research has documented evidence for a reciprocity theory (i.e., students evaluate instructors fa-vorably who would be generous in their grading; Aleamoni, 1999). The parallel to this result presented is that students who demonstrated a good work ethic were less likely to en-gage in shopping behavior—perhaps because they are more likely to be confident in their own ability rather than prospect-ing for a convenient professor. That is, negative influence of work ethic on shopping propensity does point to an expected payoff in the form of better grade to be gained from using professor reviews on the public Web sites.

TABLE 4

Results of Independent SamplestTest (N=81)

Criteria Post (n=24) Do not post (n=57) tratio p

Easy grading 21.76 25.55 1.32 .18

Personality 20.43 16.25 –2.19∗ .03

Knowledge 19.48 19.19 –0.15 .88

Challenge 8.88 7.24 –1.15 .25

Clarity in teaching 18.54 21.32 1.17 .24

Sense of humor 8.58 8.48 –0.08 .93

Appearance or looks 2.80 1.79 –1.49 .13

Note.Data are listed for shoppers only. Under the assumption of equal variances; none of the differences is significant when unequal variances are assumed.

∗p=.05.

170 T. M. HOSSAIN

The feeling of entitlement had a positive and significant impact on the likelihood of shopping, conforming to reports of the spoon-fed mentality pervasive among Generation Y learners. Grade dissatisfaction is another significant driver of shopping tendency. In other words, shopping behavior is more likely to be seen among the segment of disgruntled stu-dents. In sum, several of the independent variables explaining shopping tendency were related to grades or expectations of grades.

Thus, the findings from regression analysis conformed to predictions that students’ evaluation of teaching bears strong correlation with perceived leniency in teaching and grad-ing (Aleamoni, 1999). It should be noted that some studies failed to find statistically significant relationships between leniency and students’ evaluation (e.g., Baird, 1987). How-ever, none have found the inverse relationship (i.e., tougher grading improves students’ evaluation). Perhaps a claim can be made that grading ease has a weakly positive impact on students’ evaluations. One surprising finding in the present study regards the evidence against self-selection in online posting of professor reviews. Barring more testing with sam-ples from multiple campuses in multiple regions, a definitive conclusion on this should be withheld. Nevertheless, based on findings in the present study, perhaps online posting is a generational phenomenon by a population that thrives in a social-networking environment and loves to be plugged in all the time (Windham, 2005). I examined the attributes stu-dents deem important in a professor by active (those who post reviews) and passive shoppers (those who browse but do not leave comments or ratings). Although the sample size became somewhat smaller when investigating such a dichotomy, it is interesting that the active shoppers seemed to consider easy grading as well as personality as the primary attributes desired in instructors. The passive shopper group seemed to focus on easy grading as a single most important factor preferred in a professor. This result should suggest that, as a generalization, the ratings are perhaps less tainted by grade expectation if the relatively more grade-focused students refrain from producing ratings and comments. The passive shoppers indicated higher weights on clarity of teach-ing; however, the difference was not statistically significant. This present research suffered from a number of limi-tations, including a nonprobability sample, a limited num-ber of items tested for attitudinal constructs, and the use of exploratory and not confirmatory factor analysis. I aim to expand this research in future studies addressing these limitations. Specifically, more formal derivation of hypothe-ses based on learning theories or theories of information search should substantially enrich this research. On the mod-eling side, structural equation modmod-eling or confirmatory factor analysis may provide more reliable insights regard-ing the interrelationships between constructs. More research using primary data from students as well as faculty may surely enhance researchers’ understanding of students’ on-line information-sharing behavior regarding their professors.

REFERENCES

Akande, B. O. (2008). The I.P.O.D. generation. Diverse Issues in Higher Education, 25(15), S4. Retrieved November 3, 2009, from http://diverseeducation.com/artman/publish/article 11634.shtml Aleamoni, L. M. (1999). Student rating myths versus research facts from

1924 to 1998.Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education,13, 153–166. Aleamoni, L. M., & Hexner, P. Z. (1980). A review of the research on student evaluation and a report on the effect of different sets of instructions on student course and instructor evaluation.Instructional Science,9, 67– 84.

Allen, C. T., Machleit, K. A., & Kleine, S. S. (1992). A comparison of attitudes and emotions as predictors of behavior at diverse levels of be-havioral experience.Journal of Consumer Research,18, 493–504. Baird, J. S. Jr. (1987). Perceived learning in relation to student evaluation to

university instruction.Journal of Educational Psychology,79, 90–91. Blunt, A. (1991). The effects of anonymity and manipulated grades on

student ratings of instructors.Community College Review,18(4), 48–54. Clayson, D. E., Frost T. F., & Sheffet, M. J. (2006). Grades and the students evaluation of instruction: A test of the reciprocity effect.Academy of Management Learning and Education,5(1), 52–65.

Clayson, D. E., & Sheffet, M. J. (2006). Personality and the student evalua-tion of teaching.Journal of Marketing Education,28, 149–160. Curran, J. M., & Rosen, D. E. (2006). Student attitudes toward college

courses: An examination of influences and intentions.Journal of Market-ing Education,28, 135–148.

Dabholkar, P. A. (1994). Incorporating choice into an attitudinal framework: Analyzing models of mental comparison process.Journal of Consumer Research,10, 100–118.

Felton, J., Mitchell, J., & Stinson, M. (2004). Web-based student evaluations of professors: The revelations between perceived quality, easiness, and sexiness.Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education,29(1), 91–108. Franz, R. S. (1998). Whatever you do, don’t treat your students like

cus-tomers!Journal of Management Education,22(1), 63–69.

Gigerich, S. (2003, March 30). How does your teacher rate? Students turn to internet to find out the good, the bad and the ugly.The Washington Post, A14.

Kindred, J., & Mohammed, S. N. (2005). He will crush you like an academic ninja! Exploring teacher ratings on ratemyprofessors.com.Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication,10(3), article 9.

Lawson, R. A., & Stephenson, F. (2005). Easiness, attractiveness, and faculty evaluations: Evidence from ratemyprofessors.com. Atlantic Economic Journal,33, 485–486.

Marsh, H. W. (1984). Students’ evaluation of university teaching: Dimen-sionality, reliability, validity, potential biases, and utility.Journal of Ed-ucational Psychology,76, 707–754.

Marsh, H. W. (1987). Students’ evaluations of university teaching: Research findings, methodological issues, and directions for future research. Inter-national Journal of Educational Research,11, 255–389.

Marsh, H. W., & Roche, L. (1993). The use of students’ evaluations and an individually structured intervention to enhance university teach-ing effectiveness.American Educational Research Journal,30(1), 217– 251.

McGlyn, A. P. (2008). Millenials in college: How do we motivate them?

The Education Digest,73(6), 19–22.

McPherson, M. A. (2006). Determinants of how students evaluate teachers.

Journal of Economic Education,37(1), 3–20.

Ratemyprofessors.com. (2008). Retrieved July 23, 2008 from http://www.ratemyprofessors.com

Read, W. J., Rama, D. V., & Raghunandan, K. (2001). The relationship between student evaluations of teaching and faculty evaluations.Journal of Education for Business,76, 189–192.

Riniolo, T. C., Johnson, K. C., Sherman, T. S., & Misso, J. A. (2006). Hot or not: Do professors perceived as physically attractive receive higher student evaluations?The Journal of General Psychology,133(1), 19– 35.

Sirvanci, M. (1996). Are students the true customers of higher education?

Quality Progress,29(10), 99–102.

Vedder, R. (2008, May 19). How to choose a college: The most popular ranking use the wrong measures. Forbes. Retrieved July 16, 2008 from http://www.forbes.com/opinions/forbes/2008/0519/030. html

Whitworth, J. E., Randall, C. H., & Price, B. A. (2002). Factors that affect college of business student opinion of teaching and learning.Journal of Education for Business,77, 282–289.

Wilson, R. (1998). New research casts doubt on value of comparing adult college students’ perceptions of effective teaching with those of traditional students.Chronicle of Higher Education,44(19), A12– A14.

Windham, C. (2005). Father Google and mother IM: Confessions of a Next Gen learner.Educause Review,40(5), 42–44.

Yunker, P. J., & Yunker, J. A. (2003). Are student evaluations of teach-ing valid? Evidence from an analytical business core course.Journal of Education for Business,78, 313–317.