Assessment in social work:

A guide for learning and teaching

First published in Great Britain in August 2007 by the Social Care Institute for Excellence

© Dr Colin Whittington 2007 All rights reserved

Written by Dr Colin Whittington

Contents

List of figures 1

Acknowledgements 1

Questions and messages for educators 2

Part One: Purpose and nature of the guide 9

1 Why has the guide been created? 9

2 What is the guide about? 9

3 Who is the guide meant for? 10

4 What are the guide’s chief sources? 10

5 How was the guide created? 14

6 How can the guide assist in learning and teaching? 14

Part Two: Assessment in social work 15

The nature of assessment 15

7 The significance of assessment in social work practice and education

15

8 Reasons for teaching and learning about assessment 16

9 The definitions of assessment 18

10 Risk assessment 22

11 The purposes of assessment 24

12 Who is being assessed? 27

13 Theories that underpin assessment 28 14 The different timeframes of assessment 29

15 Assessment processes 31

16 Evidence-based assessment 32

Contexts 35

17 Legislation, legal frameworks and policy contexts 35

18 Organisational issues 36

19 Collaborative assessment with other professions and agencies

38

Service users and carers 43

21 Service user and carer perspectives on assessment 44 22 Involvement of service users and carers in assessment 46

23 User-led assessment 47

Values and ethics 53 24 Traditional, emancipatory and governance values 53

25 Anti-racist, anti-discriminatory and anti-oppressive practice

54

Part Three: Teaching and learning of assessment 56

Learning content, structure, methods and participants 56

26 What should be the content? 56

27 Sources: textbooks and assessment frameworks 63

28. How may teaching and learning be structured? 65

29. How may assessment be taught? 71

30 What should be the relationship between what is taught and assessment practice in care agencies?

78

31 Examining student competence in assessment 79 32 Whose contributions are needed in assessment teaching? 80

Other professions, agencies and academic disciplines 85

Conclusion 87

List of figures

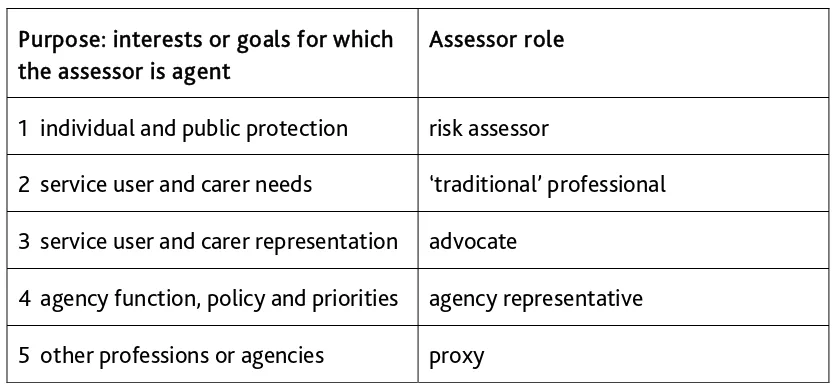

1 Five purposes of assessment 25

2 Suggestions made by members of users’ and carers’ groups about good practice in assessment

45

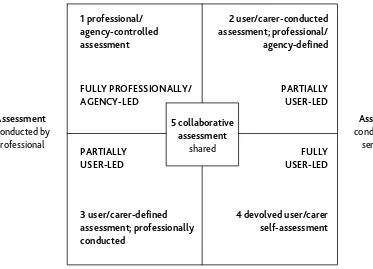

3 Matrix of five assessment models distinguished by the extent to which they are user-led

50

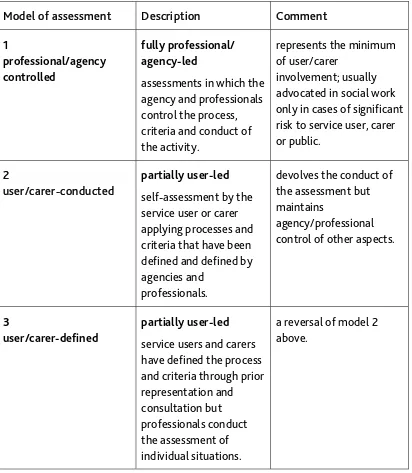

4 Further outline of five assessment models distinguished by the extent to which they are user-led

51

5 Content and tendencies in assessment learning: an abstract–concrete continuum

60

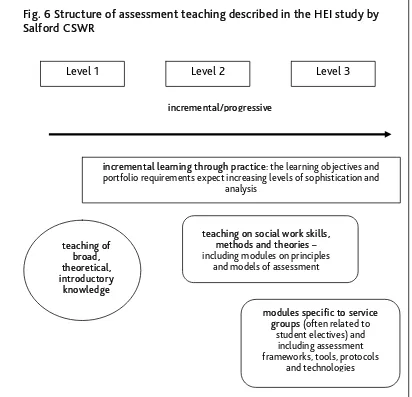

6 Structure of assessment teaching described in the HEI study by Salford CSWR

66

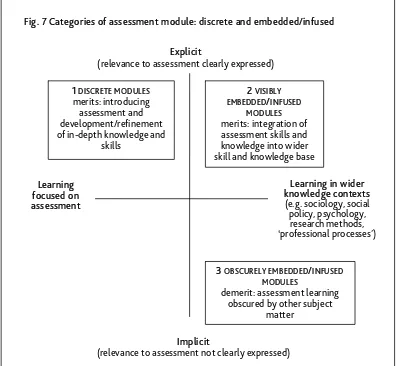

7 Categories of assessment module: discrete and embedded/infused

69

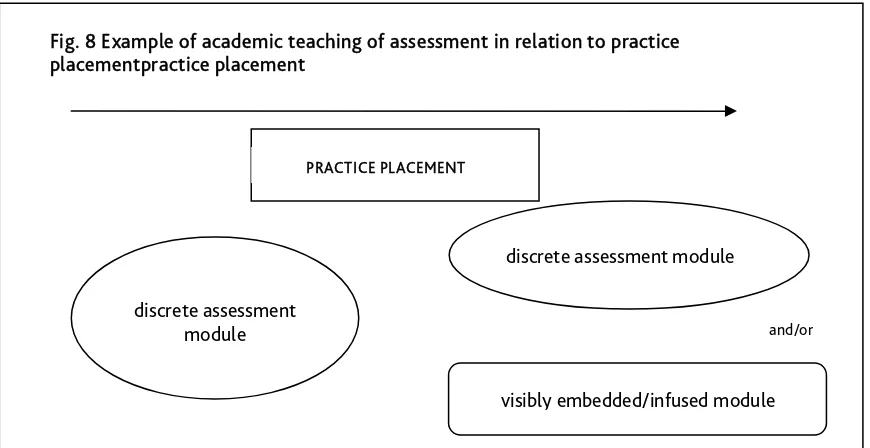

8 Example of academic teaching of assessment in relation to practice placement

70

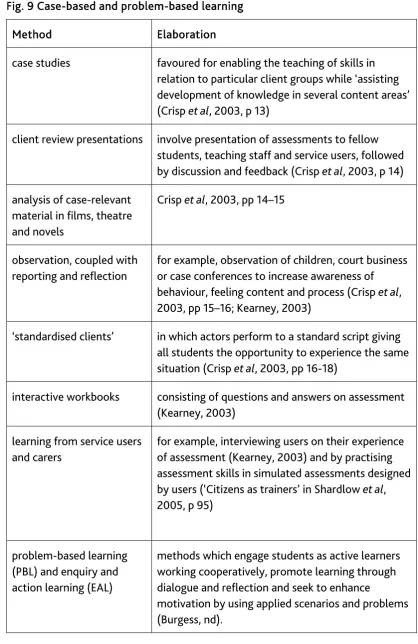

9 Case-based and problem-based learning 76

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Marie Diggins and Professor Mike Fisher for valuable advice in the preparation of this guide and Margaret Whittington for helpful

Questions and messages for educators

One aspect of the brief for this resource guide was to identify questions for

educators to consider, arising from the main sources. The questions given throughout Parts Two and Three, together with the ‘messages for educators’ in Part Three, have been collected together here to serve two purposes. They provide a prompt list for educators (or encouragement that they are addressing the key areas), and they act in place of an executive summary of the issues considered in Parts Two and Three. (Since Part Three builds on Part Two, there is necessarily some recurrence of issues.)

The extent of questions illustrates the multi-dimensional nature of social work assessment and shows the range of knowledge and skills required. The questions also indicate the scale of the task that faces educators in the design and delivery of assessment learning.

The significance of assessment in social work practice and education

• What do social work students learn about the significance placed on assessment by government and agencies, service users and carers, the professional literature and the requirements of the social work degree?

Reasons for teaching and learning about assessment

• Are there opportunities for students to consider the ‘because of’ and ‘in order to’ reasons for learning about assessment?

• What is the focus of teaching, as between technical competence, transferable principles and critical analytical skills, or some combination, and what is the rationale for the approach chosen?

The definitions of assessment

• Does teaching rely on one or more of the following four ‘types’ of definition: process-focused, contingent, contestation-focused, critical social constructionist? • What are your criteria for choosing the type(s) that are taught and examined? • What are the implications of your choices, for student learning and for students’

understanding and conduct of assessment?

Risk assessment

• In what ways does teaching on risk feature in the programme?

• Is there an opportunity to explore the contested nature of risk and the different perceptions among different groups about risk and its significance?

The purposes of assessment

• Do students have the opportunity to study the multiple purposes and interests that assessment may serve and the implications for their role?

• Are there opportunities to consider the purposes of particular kinds of assessment and to practice the explanation and negotiation of purpose with service users and carers?

• Are students able to explore the potentially dynamic relationship between purposes, the potential contradictions between them and the scope for resolving contradictions?

Who is being assessed?

• In relation to which levels or areas of ‘social organisation’ does teaching and learning about assessment take place?

Theories that underpin assessment

• Which underpinning theories appear in assessment teaching?

• What part do the theoretical and value stance and experience of the teacher and students play in the choice of theory in teaching and learning about assessment? • Are there methods for subjecting these choices (above) to independent

examination and for evaluating theories from the range on offer?

The different timeframes of assessment

• What types of assessment timeframes are taught and are there opportunities for applying or evaluating the main types?

• Are students alert to the possible variation in assessment timeframes as set by government, agency or professional criteria and of possible tensions between them?

Assessment processes

• If you are using assessment frameworks in teaching the process of assessment, does your selection allow for the variation between the level and types of guidance offered?

• If a form-based approach is included in teaching and learning, are both the pros and cons explored, including the risks of form-led assessment processes?

• Is there scope for exploring the ways in which assessment processes change over time and the factors that influence those changes?

Evidence-based assessment

• Are there opportunities for students to develop the knowledge and skills that different evidence-based approaches to assessment require?

Legislation, legal frameworks and policy contexts

• Do the learning materials you recommend:

> recognise the importance of legal knowledge in assessment?

> provide knowledge relevant to the particular national context in which students

are expecting to be employed?

> make clear the national context to which any particular legal or policy examples

refer?

Organisational issues

• Do the learning materials used pay attention to the nature of organisational employment of social workers and the implications for assessment?

• Are there opportunities to explore the politics of assessment that can surface between social worker and organisation when there are differences over goals, standards, resources or procedures?

Collaborative assessment with other professions and agencies

• Does learning for collaborative assessment feature explicitly in students’ academic and practice learning opportunities?

• What sources and learning methods do you use to ensure that both the interprofessional and inter-agency dimensions of assessment are included in student learning?

Language, communication and assessment

• What learning materials and opportunities are available to students to ensure that they understand and can act upon the multiple issues of language and

communication in assessment?

Service user and carer perspectives

• How do students learn of service users’ and carers’ perceptions, expectations and experiences of assessment?

Involvement of service users and carers

• Do teaching and learning cover the different kinds of involvement of service users and carers debated in UK social work and expected by user and carer groups and social policy?

• Do students have the opportunity to learn how users wish to be involved in the definition and exploration of their issues during assessment?

User-led assessment

• Do students have the opportunity to explore user-led approaches to assessment including:

> the nature and implications of user-defined and user-conducted or self-assessment?

> the matrix of models of assessment, from professional/agency-led to devolved user/carer self-assessment, which come into view when assessment is examined for the extent to which it is user-led.

Traditional, emancipatory and governance values

• What materials and opportunities are available to help students explore the links between values and ethics, on the one hand, and the models, methods and goals of assessment, on the other?

Anti-racist, anti-discriminatory and anti-oppressive practice

• Are there specific opportunities for students to engage with racist, anti-discriminatory and anti-oppressive principles and practice in assessment?

What should be the content?

• Do learning opportunities predominate in one area or another of the abstract– concrete continuum illustrated, (with its corresponding tendencies, types of knowledge and skills produced, and implications for practice)?

• Alternatively, does teaching cover both of the following:

> knowledge of assessment processes, including tools and assessment

frameworks

> a broader repertoire of transferable theory, principles, skills and social science

knowledge for use in assessment?

• Does the content of teaching recognise the mix of stakeholder consensus and difference about the content of the assessment curriculum?

• Are students able to identify specific areas of learning that contribute to their understanding and skills in relation to assessment?

• Are students able to identify particular formal frameworks of assessment taught on the course?

• Do students consider themselves prepared for undertaking assessments during their practice placements?

• The message from the main sources is that social workers need learning opportunities and practice skills along the abstract–concrete assessment knowledge continuum.

• Since there are limits to what can be included in any curriculum, the combination of abstract and concrete content has to be chosen for maximum transferability.

Sources: textbooks and assessment frameworks

• Textbooks and frameworks can become out of date as legislation, policy and practice change, which they do frequently.

• Textbooks published overseas or for other national contexts may offer useful insights of subjects neglected locally but should be used cautiously because of their different origin.

• There are legislative and organisational differences between the four UK countries, which may restrict the applicability of guidance to a given country.

• Reading is an insufficient basis for developing assessment expertise; learning exercises, discussion in supervision and application to practice are needed.

• Assessment as presented in textbooks and frameworks represents a complex set of skills and knowledge. Students and inexperienced practitioners need opportunities to explore and learn how to apply what they read, preferably in supervised practice. • Educators and students should be clear on the reasons for choosing particular

textbooks and frameworks.

• Students should be alerted to any limitations of recommended works and especially to changes of policy and practice since the works were written, and be directed to supplementary reading.

• Educators should be explicit about their intended audience and be sure to match content to student level and needs, as between students needing introductory knowledge and those requiring more advanced guidance.

• Educators should define how they are using the concept of assessment, bearing in mind that there is no single agreed definition.

• Learning should include case studies and exercises to encourage active learning. • The bases of theory and evidence that underpin teaching should be explicit.

• Educators should recommend further reading and identify, in particular, important topics that have not been fully covered in teaching.

How may teaching and learning be structured?

• What is the structure of discrete and embedded/infused academic learning opportunities on assessment and its rationale?

• Does the teaching and learning structure allow systematically for preparation of students for assessment before they enter practice placements?

Whatever structure, sequence and pattern of modules is chosen for teaching assessment, the clear messages from the research by Crisp and colleagues and the Salford CSWR study are that:

• programme providers should be able to articulate how the structure enables learning objectives in relation to assessment skills to be achieved

• All stakeholder groups should be able to:

> understand the assessment learning objectives of the programme

> identify when the teaching and learning opportunities have occurred.

How may assessment be taught?

• The best prospect for assessment learning seems to be a combination of approaches in which reading – and lectures, where used – are enlivened by a variety of active

learning opportunities allowing for different learning styles.

• Agency-based practice learning facilitated by supervision is highly favoured but needs support and preparation via class-based learning and guided reading for students and briefing for practice-based teachers.

What should be the relationship between what is taught and assessment practice in care agencies?

• Are there mechanisms for negotiating the respective priorities of agencies and social work courses in relation to the teaching and practice of assessment?

How is student competence assessed?

• How may the analysis of assessment in this guide inform implementation of the requirements for competence in assessment set down for the social work degree by the respective national care councils?

• What arrangements or plans are there for a service user contribution to the evaluation of students’ assessment skills?

Whose contributions are needed in assessment teaching?

• Has the requirement of service user and carer involvement in social work education been translated into assessment learning opportunities that are effective for students and sustainable for service users? If not, are reasons identified and solutions defined?

• Are agency staff and particularly practice teachers and assessors appropriately briefed on class-based objectives, teaching methods and assessment methods on social work assessment skills?

• Are there ways to ensure that learning opportunities extend beyond familiarisation with agency standard assessment forms?

• What opportunities are there for learning with, from and about other professions in relation to assessment?

• Are there learning opportunities in which students can work across agencies and understand the inter-agency and multi-agency dimensions of assessment? • Are there assessment teaching arrangements that expose social work students to

the perspectives of teachers from other professions and disciplines?

• Development appears especially to be needed in the involvement of service users and carers in students’ agency-based assessment learning.

Conclusion

• What are the distinctive ideas about assessment represented by social work programmes and their educators, and do those ideas group into a recognisable discourse or discourses?

• Do particular discourses predominate in academic or practice teaching and, if so, what influences appear to account for this predominance, giving the ideas authority and as embodying ‘truth’?

• How does a given discourse stand up against competing discourses, not only in the classroom but in a student’s placement and subsequent employed practice? • How may students be prepared to practice effectively in situations where

Part One: Purpose and nature of the guide

1

Why has the guide been created?

In 2003, SCIE initiated a series of knowledge reviews to support the introduction and subsequent development of the social work degree. The focus chosen for Knowledge Review 1 was the core social work skill of assessment and was undertaken by Crisp and colleagues (2003, p iv). The review examined the literature on the learning and teaching of assessment in social work education. The review also identified the need for further work on assessment and, accordingly, SCIE commissioned two

supplementary studies from, respectively, Crisp and colleagues (2005) and from the Salford Centre for Social Work Research (Salford CSWR) (Shardlow et al, 2005). The present guide was commissioned to provide a synthesis of ideas and issues from those three previously commissioned studies of assessment.

The guide examines aspects of assessment in social work and goes on to consider teaching and learning of assessment. The work of the three earlier assessment studies are cited recurrently but the aim is not to duplicate them. The intention is to add value to the studies by expressing their findings in ways that connect with the kinds of questions that need to be considered by educators and others involved in social work education.

Formal curriculum requirements inform the discussion but, as with other SCIE guides, the purpose is not to prescribe a curriculum for the teaching of assessment. The purpose is to explore the issues and choices that have to be made by those involved in providing teaching and learning of assessment in social work education.

2 What is the guide about?

The guide uses the three SCIE resources on assessment to:

• examine aspects of assessment in social work

• consider approaches to teaching and learning of assessment

• pose issues and questions for social work educators to consider when planning and reviewing teaching and learning of assessment.

3 Who is the guide meant for?

The guide is primarily for educators in the social work degree but is also relevant to other levels of teaching and learning. The term educators covers a wide spectrum which includes university teachers, practice teachers and assessors and service users and carers or, as Braye and Preston-Shoot express it, ‘experts by experience’ (2006). The guide is relevant to students of the degree in thinking about both the subject of assessment and their own learning, whether they are learning alone or with other students and educators. This description does not exhaust the list of stakeholders who may have an interest in the guide and who may also participate in the educator role. Others include practitioners and managers of service-providing agencies, members of the different professions who may contribute to university-based and agency-based learning, and authors and researchers.

The guide also provides the opportunity for educators and students learning at post-qualifying levels to revisit and review issues of assessment. The analysis in Part Two addresses the nature of assessment, its contexts and participants, and values and ethics. This analysis is arguably relevant to students, educators and practitioners at many levels.

4 What are the guide’s chief sources?

The three primary sources used for the guide are outlined below. The nature of each is summarised by the ‘Question answered by the research’ and by a description of the sampling strategy and data collection method.

Source 1

Crisp, B.R., Anderson, M.R., Orme, J. and Lister, P.G. (2003) Knowledge Review 01: Learning and teaching in social work education: Assessment, London: Social Care Institute for Excellence.

Question answered by the research

What does the literature say on how learning and teaching of assessment skills in social work and cognate disciplines occurred in the classroom and practice settings?

Sampling strategy and data collection

Crisp and colleagues sought literature about learning and teaching of assessment using the following sources:

• conference abstracts • electronic discussion lists

• requests for information posted to selected listservers and the SWAPltsn website.

The search identified 60 journal articles that met the search criteria. The majority (nearly 50) were from the USA and England with the remainder distributed among several other countries. The articles were classified under the following headings: country of focus; target group; what was taught and how?; and was the teaching evaluated? (pp 93–4).

Source 2

Crisp, B.R., Anderson, M.R., Orme, J. and Lister, P.G. (2005) Knowledge review: Learning and teaching in social work education: Textbooks and frameworks on assessment, London: Social Care Institute for Excellence.

The study was designed to supplement the knowledge provided by Source 1. The focus on textbooks reflected the substantial potential influence of these sources on social workers’ learning. The focus on assessment frameworks responded to the increasing use of these tools in both social work practice and education.

Question answered by the research

What might a reader and, especially, a beginning social work student or unqualified worker, learn about assessment from a) textbooks and b) assessment frameworks?

Sampling strategy and data collection

Social work textbooks were sought in two categories: textbooks with a substantial section (one or more chapters or an identifiable section) on assessment; and textbooks entirely on assessment. The books selected were required to have a generalist focus (as distinct from a concern with a specific problem or service group), be currently available in the UK and have a publication date between 1993 and 2003.

A search of introductory texts located ten books with one or more chapters on assessment and six texts specifically about assessment. Three texts were from outside the UK, two being from the USA and one from Australia. A further ten introductory texts were excluded, having no chapter on assessment.

The reviewers collected data from the chosen 16 texts using a proforma covering three kinds of characteristics:

• basic information, such as title, author and intended audience

• qualitative features, like accuracy, comprehensiveness and inclusion of features to improve learning.

Turning to frameworks, there is no standard definition of the term ‘assessment framework’. Crisp and colleagues therefore devised the following criteria for the selection of frameworks, which should:

• propose a conceptual, philosophical or theoretical basis for assessment practice or some combination

• not be chiefly a data collection tool • have been devised:

> for work with clients in the UK

> for national rather than local use

• be accessible without charge over the internet

• be currently recommended for use with specific service populations • not have been superseded.

Searches identified four examples of standardised frameworks: they were published between 2000 and 2003 and governed assessment with children and families, carers and disabled children, older people and drug users. Each framework was examined to explore its potential ‘to educate students and workers about the assessment process more generally than in relation to the specific population for which it was designed’ (p 39). Again, a proforma was used to collect data, applying similar categories to those used for the textbooks. Further information on the textbooks and frameworks studied by Crisp and colleagues is given in Section 27 of this guide.

Source 3

Shardlow, S.M., Myers, S., Berry, A., Davis, C., Eckersley, T., Lawson, J., McLauglin, H. and Rimmer, A. (2005) Teaching and assessing assessment in social work education within English higher education: Practice survey results and analysis, Salford: Salford Centre for Social Work Research (available from Salford CSWR, University of Salford, Salford, Manchester M6 6PU).

Question answered by the research

What kinds of practices are found in the teaching and learning of assessment on social work programmes and in relation to inclusion of service user and carer perspectives in teaching and learning?

Sampling strategy and data collection

service users and carers, service-giving agencies providing practice learning opportunities, and former social work students.

Ten HEIs offering qualifying social work education in England responded to a questionnaire on assessment in 2003/4. The information gathered was used, in 2004/5, to inform site visits to a further 13 geographically-dispersed HEIs. The HEIs had volunteered from a selection of 20 chosen for their reputation as providers of ‘exemplary teaching and learning opportunities’ (Shardlow et al, 2005, p 17). At the visits, interviews were held with 21, mainly academic, staff although a small number of practice assessors participated too. Examples were collected of teaching materials in use.

Service users and carers were consulted by focus group discussion with seven groups based in north-west England and selected on advice from Citizens as Trainers (CATs) who had two members on the research team. Participants had greater or lesser experience of educating social workers and were chosen to include difference by age and reason for involvement with social work and to ensure representation of

minority ethnic groups.

The research with agencies and practitioners was designated as ‘illustrative studies’ to recognise the limited samples and the use of the findings to illustrate issues in assessment. The studies consisted of: completed questionnaires from five agencies (four not-for-profit and one local authority social services department) involved in providing social work placements; and 23 qualified social workers from a single cohort of candidates undertaking a post-qualifying child care award. All but one of the social workers held the DipSW, each gaining the award from one of six different HEIs. Ten of the social workers had qualified in 1999 or after and the remainder, except one, between 1994 and 1998.

Other sources for the guide

The guide draws on a further set of sources comprising the requirements for the social work degree issued by the national care councils of the UK. There are national variations of emphasis in these requirements but they have common roots in three sources:

• national occupational standards for social work (TOPSS UK Partnership, 2002) • subject benchmark statements: social policy and administration and social work;

academic standards – social work (QAA, 2000)

• codes of practice developed jointly by the national councils (CCW, 2002; GSCC, 2002; NISCC, 2002; SSSC, 2003).

must consider. Other SCIE guides and relevant sources are also cited in the text and used to clarify or develop the discussion.

5 How was the guide created?

The studies by Crisp and colleagues and by Salford CSWR were analysed in two stages by treating their content like the data of a qualitative study (Ritchie and Lewis, 2003). In the first (non-cross-sectional) stage, each source was examined to identify assessment themes and concepts relevant to educators in the social work degree. In the second (cross-sectional) stage the resulting categories were combined into a common framework which was applied across the whole set of sources. This process modified or confirmed the usefulness of categories and resulted in the structure of sections for this report and the allocation of content. The categories were then used to structure the examination of national requirements for the social work degree and, to a lesser extent, other relevant literature.

6 How can the guide assist in learning and teaching?

Part Two: Assessment in social work

Part Two identifies the main dimensions of assessment as represented in the key sources for this guide. It also provides a platform and set of reference points on key issues for Part Three, on teaching and learning. The aim of the guide is not to prescribe curriculum content but the following sections and their ‘questions for educators’ may be used to clarify aspects of the curriculum.

The nature of assessment

7 The significance of assessment in social work practice and

education

The idea of professional or organisational assessment is an inherent feature of contemporary practice in care services. Professional or organisational assessment represents the entry of an intentionally rational and systematic approach to the encounter between a social worker and people seeking help or services, who may be individuals, couples, families, groups or communities. The assessor’s role may be conceived as gatekeeping, facilitating or empowering but, whichever is the case, the application of some form of assessment implies that a service does not operate entirely on-demand or that special expertise in defining problems or finding solutions exists or is needed. There is a further realm of assessment, namely user-led

assessment, that has emerged to modify aspects of the picture of assessment described above and which will be discussed later.

The confident statement in the preface to SCIE’s first knowledge review that social work assessment is ‘a core social work skill’ (Crisp et al, 2003, p iv), is supported in a number of quarters, as this guide will show. To summarise:

• government and agency policies and practices place great store in effective assessment

• the assessment process is significant for service users and carers in both conditioning their experience of the encounter with social care services and in shaping the service they receive

• assessment is widely portrayed in the social work literature as fundamental to social work practice with some accounts defining it as a key part of intervention and others regarding it as the essence of social work intervention

In short, of all the skills that social workers may aspire to, assessment seems the one most likely to achieve consensus among practitioners, managers, employers and service users as an essential skill. Agreement as to what constitutes assessment is, however, more elusive, as will be shown later.

Question for educators

• What do social work students learn about the significance placed on assessment by government and agencies, service users and carers, the professional literature and the requirements of the social work degree?

8 Reasons for teaching and learning about assessment

The question ‘why teach and learn about assessment?’ prompts two kinds of response: ‘because of ...’ and ‘in order to ...’. These categories are not sharply distinguishable but provide a convenient way of grouping the factors involved.

Because of …

As outlined in the preceding section, social workers should learn about assessment because of:

• the requirements placed upon degree programmes • the significance attached to assessment by:

> services users and carers > employers of social workers

> the profession and its many writers and commentators.

The position is summed up in the study by Salford CSWR:

Assessment is a central concern of learning and teaching within HEIs [higher education institutions], partly driven by guidance but also in recognition of the importance of this task within contemporary practice’.

(Shardlow et al, 2005, p 20)

In order to …

• enhance the quality of information gathering • make assessment empowering

• understand the determination of eligibility

• provide access to solutions and the most suitable services • offer sensitivity and support at a time that is often stressful.

Technical vs. critical

Consideration of some ‘in order to’ questions begins to show the contested nature of assessment. For example, a recurrent debate concerns whether teaching and learning about assessment are in order to produce social workers who are:

• technically competent at the task or

• critical thinkers about the task.

Critical thinkers would possess a knowledge base that enables them to examine the assessment tools they may be asked to use and recognise underlying assumptions, for example about the nature or causes of need. A related debate concerns whether social workers should learn the use of particular assessment frameworks or wider ‘principles’ of assessment that are transferable between settings and kinds of assessment.

There is evidence from the Salford CSWR study that some social work educators feel under pressure from employers of social workers to focus teaching on technical competence in assessment. Service users and carers also have a clear interest in assessment being done in a way that is technically competent. This expectation is plain from the consultations undertaken for the development of the social work national occupational standards (NOS) (TOPSS UK Partnership, 2004).

Similarly, evidence from consultation on law teaching with ‘experts by experience’ for the SCIE Resource guide 06 indicates that they strongly support education for technical competence, a view that was conditioned by the experience that some social workers did not know the law (Braye and Preston-Shoot, 2006, p 3). However, both the consultations for the law guide and the NOS suggest that service users and carers do not want learning to stop at the level of technical competence. The law guide reports that experts by experience want social workers who are critical thinkers as well. Furthermore, the expectations recorded in the NOS seek social workers whose assessments are creative, review all options within and beyond those immediately available and include the ability to challenge the worker’s employing organisation (TOPSS UK Partnership, 2004, p 3).

professional standards which include emancipatory values in relation to service users; and second, the regulators of social work education working through standards and benchmarks.

Learning that is restricted to technical competence renders the social worker more bureaucrat than professional and creates over-dependence on the perspectives of the authors of technical assessment tools. Consequently, the social worker’s ability to recognise and question a conservative or illiberal assessment tool may be restricted, with corresponding limits on his or her capacity to represent the interest of the service user. It is of note that, while the social work NOS expect social work assessment to be technically proficient, they also make it clear that assessment should be a process of participation and exploration with the service user and should be underpinned by knowledge of models, methods, causes and needs (TOPSS UK Partnership, 2004, Key role 6). In addition, the subject benchmarks statement for social work expect reflective and critical analysis of evidence, a skill that is plainly relevant to assessment (QAA, 2000, para 3.1.4).

Questions for educators

• Are there opportunities for students to consider the ‘because of’ and ‘in order to’ reasons for learning about assessment?

• What is the focus of teaching, between technical competence, transferable principles and critical analytical skills, or some combination, and what is the rationale for the approach chosen?

9 The definitions of assessment

Assessment is widely agreed to be of great importance, but that is where agreement ends and contestation over what it is begins. For the purpose of their literature review, Crisp and colleagues stated that assessment ‘involves collecting and analysing information about people with the aim of understanding their situation and determining recommendations for any further professional intervention’ (2003, p 3). Two years later, however, their review of textbooks concluded that there is no single definition and the review of assessment frameworks found the same (Crisp et al, 2005). This conclusion can be confirmed by reference to the summaries of reviewed textbooks and frameworks provided by Crisp and colleagues in their appendices.

and perspectives that help in reflecting upon approaches to assessment. The analysis suggests four types of definitions found in the textbooks and frameworks reviewed by Crisp and colleagues:

• process-focused • contingent

• contestation-focused

• critical social constructionist.

This simple, four-part typology conceals variation, especially among process-focused definitions which predominate in the works reviewed by Crisp and colleagues (2005). Furthermore, while some reviewed approaches to assessment fall very clearly into one or another of the types, other approaches overlap the types. Overlap is most likely to be found between process-focused and contingent types. Contestation and critical constructionism represent different theoretical paradigms from the others and are less likely to combine elements with them, although they do overlap with one another insofar as they share a critical perspective on contemporary policy or practice.

Process-focused

The process-focused group of definitions concentrates on assessment as an essential, practical function that must be carried out with professional sensitivity and

competence. Of all the approaches, process-focused definitions are the nearest to an implicitly technical, even ‘scientific’, view of the assessment task as a set of methods to be learned and professionally applied. The concept of assessment itself is not thought to raise fundamental questions. Attention is directed to providing clear guidance on what to do, what questions to ask and procedures to follow, in making an assessment. Examples combine, in some form, the activities of information-gathering from service users and carers and other sources, exploring facts and feelings, analysis, understanding the situation, making judgements and determining action or recommendations. These activities may be found in the other types, including the critical social constructionist type, but there the very idea of assessment is treated as problematic and activities such as analysis and understanding the situation are used to question the process itself.

Process-focused approaches vary on a number of dimensions. They are:

• more or less oriented to judgements based on professional or organisational criteria and procedures

• more or less oriented to need, eligibility, service user aspiration or resource availability

The approaches also vary by their conception of assessment as:

• a distinct stage

• a series of distinct stages

• a fluid and dynamic process throughout the life of the ‘case’.

Contingent

The contingent type has some similarities with the process approach but is

contingent in the sense that the nature and direction of assessment is taken to differ according to particular independent factors. It is implied either that the approach to assessment is determined by a given independent factor, or variable, or that a given approach to assessment is particularly suited to that variable. Variables that are influential on assessment include:

• the type of service for which assessment is being made • the goals of assessment

• the conceptual framework or map chosen to make sense of assessment.

Contestation-focused

The contestation-focused type differs from process-oriented approaches in not viewing assessment procedurally, but shares with contingent approaches the recognition that other variables condition assessment. However, the focus is on the conflict or contestation between variables. Hence, the approach defines assessment as an area of contestation between different policies, perspectives and priorities represented, for instance, by:

• emphasis on need vs. eligibility • social worker idealism vs. realism • needs vs. risks vs. resources.

Critical social constructionist

The critical social constructionist type proceeds from the view that the act of

assessment involves the construction of meanings as distinct from the determination of objective facts and causes of problems. The understandings that constitute

The critical aspects of the approach are found in the challenge to traditional, process-focused definitions of assessment and in the analysis of unequal power both in the assessment relationship and in the ideas and policies that influence those involved. Together with this critique, the approach envisages ways of thinking about and doing assessment that reflect on the narrative construction process and shape it in the interests of service users and carers. The critical social constructionist type shares aspects of its approach with the ‘exchange model’ of assessment, which recognises that people are experts in their own problems and should be engaged by the social worker in a collaborative exchange to define and tackle issues (Smale et al, 1993 and 2000).

The contestation and critical social constructionist approaches treat the idea of assessment as problematic. They provide critical perspectives on:

• the social and political contexts of assessment

• other assessment approaches that take social and political contexts for granted.

Neglect of social and political contexts may stem from the professional’s

preoccupation with the skilled conduct of the assessment process. Yet a process dimension is inescapable for social workers and their educators. In some form, a repertoire of technically and professionally proficient steps of the kind described in some textbooks and practice guides (Nicholls, 2006), is indispensable if assessments practice is to take place. But it is also important for the social worker to be able to submit the process to critical review and revision. To be able to do so, social work students need to encounter all of the types in their learning. The case for this strategy echoes the earlier debate between technical and critical competence.

The Salford CSWR study observes that the lack of consensus about what constitutes assessment and its contested nature raise fundamental questions for educators and students in deciding what should be taught and the methods to be used (Shardlow et al, 2005, p 47). There are no absolutes in responding to these questions but later discussion will set out and discuss the kinds of choices unearthed by the SCIE-commissioned assessment studies.

Questions for educators

• Does teaching rely on one or more of the following four ‘types’ of definition: process-focused, contingent, contestation-focused, critical social constructionist? • What are your criteria for choosing the type(s) that are taught and examined? • What are the implications of your choices, for student learning and for students’

10 Risk assessment

Risk assessment is a significant component of many assessments and requires discussion in its own right. Risk is mentioned only briefly in the analysis above but risk issues could feature in all of the definitional types.

Risk is an aspect of assessment in a number of social work textbooks, more notably those published in the UK (Crisp et al, 2005). Risk is also a common feature of the four assessment frameworks reviewed by Crisp and colleagues, a fact that reflects the authorship of the frameworks by UK government agencies and the resolve of governments to place issues of risk at the forefront of policies in social care and health. This resolve gains strength from the significance attached to risk issues in several public inquiries. In England, the Victoria Climbié Inquiry reported on the essential elements of future good practice in childcare, stating the importance of training in risk assessment and risk management (Secretaries of State, 2003, para 17.61). In Northern Ireland, lack of awareness of risk factors at management and operational levels were defined as significant failings in the cases of the children David and Samuel Briggs (DHSSPS, 2005). These examples illustrate the concern over children at risk, but worry about risk also, for example, ‘permeates assessment work with older people’ (Nicholls, 2006, Sec. 3).

Risk can be defined as ‘the possibility of beneficial and harmful outcomes, and the likelihood of their occurrence in a stated timescale’ (Alberg et al in Titterton, 2005).

The aim of risk assessment is to consider a situation, event or decision and identify where risks fall on the dimensions of ‘likely or unlikely’ and ‘harmful or beneficial’. The aim of risk management is to devise strategies that will help move risk from the likely and harmful category to the unlikely or beneficial categories. An enlarged idea of risk management based around the concept of ‘safeguarding incidents’ introduces the idea of professional and organisational learning from near misses (Bostock et al, 2005).

Most models of risk assessment recognise that it is not possible to eliminate risk, despite the pressure on public authorities to adopt defensive risk management (Power, 2004). There are attempts to counter these defensive tendencies via person-centred risk assessment (Titterton, 2005) and the urging of some service users who advocate non-paternalistic models of assessment and care and seek support for calculated, beneficial risk-taking (Department of Health, 2005). There is also growing institutional resistance represented by the Better Regulation Commission, which has declared that ‘enough is enough’ and argue that it is time to reverse the incremental drift into disproportionately burdensome risk regulation (Berry et al, 2006).

subject. As with definitions of assessment, no common approach to risk was found. Treatment of risk varied from the detailed, including case examples, to the brief, with some books not mentioning risk at all in the context of assessment (Crisp et al, 2005, p 21). This finding suggests that educators need to choose teaching texts carefully if important subject matter is not to be omitted.

A key purpose of all four assessment frameworks is the identification and

management of risk. However, the objectives of the frameworks are different and therefore the nature of risks that are of concern are different too. The frameworks for assessment of children and families and of older people addressed service-user vulnerability and avoidance of significant harm, and, in relation to older people, loss of independence. The guide on carers’ assessment focuses on the risk of breakdown of the carer role (Crisp et al, 2005, p 47). This finding suggests that the learning offered by each framework differs and any one may be insufficient to cover the necessary range of the subject.

The requirements of the social work degree directly support attention to learning on risk assessment. Key role 4 of the NOS and the social care code of practice both cover assessment of risk. Reflecting the less risk-averse approach described above, however, both the NOS and the codes also expect social workers to respect risk-taking rights and to help inform risk-risk-taking. Service user and carer interests, consulted on their expectations for the NOS, sought support for appropriate risk-taking (TOPSS UK Partnership, 2004, para 2j). The NOS augments these liberal aims with a set of expectations that both contextualise the risk assessment role and convey its complexity. Social workers are expected to balance rights and

responsibilities in relation to risk, regularly re-assess risk, recognise risk to self and colleagues and work within the risk assessment procedures of their own and other organisations and professions (Key role 4).

Questions for educators

• In what ways does teaching on risk feature in the programme?

• Is there an opportunity to explore the contested nature of risk and the different perceptions among different groups about risk and its significance?

• Bearing in mind both the variable levels of attention to risk that may be found in textbooks and the different kinds of risk that preoccupy assessment frameworks, what are the main teaching and learning sources?

11 The purposes of assessment

But then there is the evaluation of risk and of urgency. And so the debate may go on, dispelling any sense that the purpose of assessment is self-evident. It is not surprising that the review of the literature by Crisp and colleagues found that social workers undertake assessments for a range of purposes and that there is no consensus on what those purposes are (Crisp et al, 2003).

The response to the question of purpose will vary according to the level at which purpose is being analysed. The examples given above, about need, eligibility and so on, tend to imply person-centred encounters between the social worker and, say, an individual or family. If the focus shifts from this inter-personal level to the wider societal level and endeavours to link the two, different concepts come on to the agenda. It becomes possible to see assessment as a small but significant operational step multiplied hundreds and thousand of times across agencies in the service of groups of policies or more general social, economic and political goals.

For example, assessments are shaped by policies to protect vulnerable children and adults, to integrate people who are socially excluded and to prolong or improve independence and the ability to work. These care-focused social objectives connect with other, control-oriented goals that are also part of the influence on assessment and condition its purpose, especially in the statutory sector and among the agencies the sector commissions: for instance, control of abusers, management and reform of offenders, rationing of demand and containment of public sector costs.

Looked at in this way, assessment becomes not only multi-faceted but multi-layered in ways that are seldom visible in the assessment encounters of individuals. The wide reach of assessment is demonstrated in the view that assessment has for many years been ‘an important tool for policy makers to achieve greater efficiency and

effectiveness’ in services (Clarkson et al, 2006). The importance and distinctiveness of the assessment encounters of individuals are not diminished by the wider analysis. Assessment is one of the key arenas in which, influenced by service and policy

objectives, particular versions of ‘clienthood’ are constructed or revised (Hall et al, 2003). Individual assessments may be made on the basis of ‘professional judgement’ or a set of independent, agency criteria, but both are carriers of judgements and priorities formulated outside the assessment situation.

It is evident that assessment does not have a purpose but purposes. One way to explore the picture further is to ask, ‘for whom or what is assessment being undertaken?’ and to concentrate on where the main emphasis is found. This

Fig. 1 Five purposes of assessment

Purpose: interests or goals for which the assessor is agent

Assessor role

1 individual and public protection risk assessor

2 service user and carer needs ‘traditional’ professional

3 service user and carer representation advocate

4 agency function, policy and priorities agency representative

5 other professions or agencies proxy

1 Risk assessor

All four assessment frameworks reviewed by Crisp and colleagues (2005) were centrally concerned with protection and risk, supporting the view that concern with risk is a significant element of social care services. The purpose is the protection of individual service users and carers, other members of the public and staff. In a different sense, the aim is also protection of the agency from liability and reputational risk (Whittington, 2006).

National codes of practice for care workers emphasise the role of risk assessor and protector of service users (CCW, 2002; GSCC, 2002; NISCC, 2002). The related concern of wider public protection and safety (Ritchie et al, 1994; Francis et al, 2006) is a duty of care services across the UK, driving efforts at cooperation between departments and appearing explicitly in the title of some responsible departments, such as the Northern Ireland Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety.

2 ‘Traditional’ professional

In this typically person-centred manifestation, the purpose of assessment focuses on needs and expectations, problems and solutions, and weaknesses and strengths, mediated by the social worker’s professional judgement. The level of involvement of the service user may vary from recipient through contributor to active partner. In some cases the worker is a facilitator whose enabling role, as outlined in the NOS, helps users and carers themselves to assess ‘their needs, circumstances, risks,

3 Advocate

Key role 3 of the NOS introduces the idea that social workers must assess the kind of role they are needed to play in a given case and to judge whether, for instance, they should act as advocate. This statement adds weight to the contention here that the assessment process not only constructs the role of client, as indicated earlier, but also of worker. The role of advocate connects with a set of expectations recorded from consultations with representatives of service users for the NOS (TOPSS UK Partnership, 2004). According to the consultation, social workers are expected to help others to represent themselves, advise on and involve independent advocacy, challenge lack of access to services and challenge their own organisation on behalf of others, seeking new service options where they are needed (TOPSS UK Partnership, 2004; Crisp et al, 2003, pp 1–2).

4 Agency representative

This role is characterised by the task of implementing agency policy and priorities. It may conceivably incorporate any of the other roles and purposes discussed here but its main characteristic is that the worker’s primary reference point is what the agency requires and is there to do, sometimes called ‘agency function’. The agency’s function and related resources and duties are empowering to workers and their assessment role. However, functions and resources are also defined and given boundaries. Assessment may contribute to that boundary-keeping by determining eligibility, distinguishing priorities and rationing services. Assessment also commonly plays a key part in defining the element of social control that should be part of any

intervention, again deriving its authority from the agency function. It is not hard to see the potential for tension between service-providing and rationing and between care and control, or for conflict with the other roles and purposes described in this section.

5 Assessor as proxy

The clearest example of this purpose is when the social worker is engaged in

The five categories of purpose and agent have been described separately but in the real world of practice they are found in various combinations. Their relationship is dynamic. One purpose may tend to predominate in a particular assessment or type of employing agency with other purposes coming into play and even competing as the assessment process unfolds.

Questions for educators

• Do students have the opportunity to study the multiple purposes and interests that assessment may serve and the implications for their role?

• Are there opportunities to consider the purposes of particular kinds of assessment and to practise the explanation and negotiation of purpose with service users and carers?

• Are students able to explore the potentially dynamic relationship between purposes, the potential contradictions between them and the scope for resolving contradictions?

12 Who is being assessed?

The historical development and strongly statutory base of much social work in the UK have been associated particularly with work with individuals and families. Typically, assessment and the tools and frameworks that support it assume intervention to be at these levels. Work with groups and communities has always been recognised in training and practice, and Crisp and colleagues note that newly qualified social workers are expected to have some understanding of assessment in relation to these levels too (2003, p 1).

Social workers have commonly encompassed parties other than service users in their assessments, for example, by considering the suitability of service providers to meet the requirements of a given service user. This is one of many judgements that are made as a consequence of the assessment process and consideration of the means for meeting service user needs or goals. The primary focus of assessment has nevertheless remained on the service seeker, the individual, partners, family and carer and, to a lesser extent, the group or community. However, the growth of interprofessional and inter-agency practice has made the perspectives and

contribution of other professional and agency stakeholders an increasing feature of the assessment process.

Question for educators

• In relation to which levels or areas of ‘social organisation’ does teaching and learning about assessment take place?

13 Theories that underpin assessment

The question of whether there is a theory that underpins assessment is sometimes asked and debated without saying what is meant by theory and its relationship to assessment, so some clarification is needed. Theory and assessment have two possible relationships.

In the first relationship, a theory about assessment examines and seeks to explain its nature and processes or the social or political functions it performs. The critical social constructionist perspective (see page 20) offers one possible theory about

assessment.

In the second relationship, a theory of or, more precisely, for assessment suggests the possible existence of a systematic set of ideas that informs what information is collected, how to collect it and how to use it in forming understandings and

recommendations. At its best, the theory would be underpinned by understandings of human experience and action, offer explanation of the situation being assessed and how to respond, and be supported by compatible models and tools for conducting the assessment.

The Quality Assurance Agency subject benchmarks for the social work degree suggest that this is precisely the kind of theory that students should be learning. For example, the benchmarks expect students to understand theories on the causes of need and about models and methods of assessment (QAA, 2000, 3.1.4/5).

The use of ‘theories’ in the plural in the preceding sentence gives away a particular complication that faces educators, students and practitioners. As Crisp and

conclusion is supported by the Salford CSWR study of higher education institutions teaching social work programmes (Crisp et al, 2003, p v; Shardlow et al, 2005, p 47). The Salford study found that students are not being prepared for a single paradigm or approach to assessment and suggests that different approaches are shaped by the teacher’s own theoretical and value stance and mediated by the level of the

student’s own knowledge, skill, values and theoretical position.

There is no lack of underpinning theoretical perspectives on offer, although they are more likely to be found in textbooks than in the frameworks examined by Crisp and colleagues. Only the children’s framework discusses the need to underpin practice with theory but does not identify specific theories (Crisp et al, 2005, p 47).

The textbooks offered a variety of different theoretical underpinnings to assessment including:

• from psychology and social psychology: behavioural theory, psychodynamic approaches and solutions-focused and task-focused perspectives

• varieties of post-modern perspectives, including narrative and discourse analysis and critical constructionism

• models based on systems theory and social exchange theory (Crisp et al, 2005, p 19).

The reviewers suggest that the plurality of theories for assessment may account for the diverse advice given to readers on the information they should collect in

assessments (Crisp et al, 2005, p 19).

Questions for educators

• Which underpinning theories appear in assessment teaching?

• What part do the theoretical and value stance and experience of the teacher and students play in the choice of theory in teaching and learning about assessment? • Are there methods for subjecting these choices (above) to independent

examination and for evaluating theories from the range on offer?

14 The different timeframes of assessment

Timeframes, that is, duration of focus, on assessment may vary with the service, setting or nature of the problem or issue. Timeframes may also vary according to factors already described, including the definition and purpose of assessment and the underpinning theory that informs it.

assessment-focused contacts with service users and carers over an extended period (Crisp et al, 2003). The ongoing approach acknowledges that the needs of clients change over time, especially following critical events (Crisp et al, 2005, p 47). The Salford CSWR study found both time-limited, briefer models and longer-term assessment models (Shardlow et al, 2005, p 47).

An analysis of the textbook summaries provided by Crisp and colleagues (2005) suggests that there are four chief types of assessment timescale:

• ongoing

• a recognisable, time-limited stage or point in the history of a ‘case’ • a combination of recognisable stage and ongoing

• variable between ongoing and recognisable stage depending on the situation.

There is a fifth position in the textbook summaries that sees assessment as inseparable from intervention and service delivery (Crisp et al, 2005, pp 157–8).

Some authors clearly advocate one or other of the four types outlined above, some describe what they have observed, while others advocate one model, typically the ongoing kind, but comment that it is often not achieved because of a range of constraints (Crisp et al, 2005, pp 90, 153).

Three of the four assessment frameworks were found to view assessment as an ongoing process rather than taking place at a fixed point in time (Crisp et al, 2005, p 47). However, particular timeframes may be differentiated within the overall process. Hence one of the three, the children’s framework, distinguishes ‘initial assessment’ – 7 days – and ‘core assessment’ – which must be completed within a maximum of 35 working days (Department of Health, Department for Education and Employment and the Home Office, 2000, para 3.11). The document also refers to ‘specialist’ commissioned assessment.

It should be noted that timeframes and targets for assessment set by government and agencies vary over time and between service user groups and are subject to review. This variation means that practitioners need to know the prevailing

requirements of their agency. There may be tensions between some agency target times and some professional timeframes or between either of these and the staff time available.

Questions for educators

• Are students alert to the possible variation in assessment timeframes as set by government, agency or professional criteria and of possible tensions between them?

15 Assessment processes

Crisp and colleagues found differences among and between textbooks and frameworks in the extent of information offered on the assessment process. The framework for children and families offered as much detail on the assessment process as many of the textbooks reviewed, and possibly more. By contrast, the framework for older people provided relatively little on process, taking readers to be skilled already in assessment (Crisp et al, 2005, p 56).

However, the reviewers comment that each framework includes some expectations about the assessor and the assessment, covering factors such as interview

timeframes, expected information, content of the report and matters of consent, confidentiality and disclosure (Crisp et al, 2005, p 49). Some frameworks also offer structured recording instruments and supplements giving suggested tools. This applied, for example, to both the children and families framework and the framework for integrated care of drug users (Crisp et al, 2005, App 4). However, the authors of the children and families framework are at pains to point out that the aim is to offer a conceptual map for systematic analysis and recording rather than a practice manual (Crisp et al, 2005, p 164).

The national occupational standards (NOS) for social work do not set out detailed learning expectations on the assessment process. The same is true of the

requirements of the pre-registration ‘assessed year in employment’ (AYE) for newly qualified social workers in Northern Ireland (NISCC, 2005a). The requirements for the degree and for AYE are defined by the six NOS key roles. The six roles are expressed in line with the NOS task of stating outcome standards but leaving

detailed content for determination by educators, learners and employers (TOPSS UK Partnership, 2004). Hence the NOS opt for outlining a project management-like sequence in which assessment, goals and planned action are linked to planned outcomes and modified by regular reassessment of risk (Key role 1, unit 3).

Two views arise from the analysis by Crisp and colleagues of the treatment of process in the frameworks (Crisp et al, 2005, p 57).

• Assessment frameworks do seem to offer a useful contribution to learning,

• No assessment framework can be assumed to be suitable generally for teaching students about assessment. Educators will need to evaluate and select carefully to ensure that chosen frameworks cover what is required.

When Crisp and colleagues turn to textbooks, they confirm a theme predictably familiar from other strands of their analysis. There was no common

conceptualisation of the assessment task. The reviewers also note that the focus of the assessment process varies. Assessors are in some cases encouraged to use lists of questions, domains to be covered or assessment tools. In other cases the emphasis is on critical understanding of the process and assumptions that are made about service users and their needs.

Furthermore, the information to be collected shifts over time with the emergence of new or competing theories and philosophies: for instance, from the diagnostic, psychoanalytic approach to correlation of variables associated with offending; from a focus on problems and deficits to solutions and strengths; and from resource-led assessments to needs-led assessments with the advent of community care reforms in the early 1990s (Crisp et al, 2005, p 20). There are echoes here of earlier discussions and links to the idea that assessment is constructed professionally, culturally, organisationally, politically and economically.

Questions for educators

• If you are using assessment frameworks in teaching the process of assessment, does your selection allow for the variation between the level and types of guidance offered?

• If a form-based approach is included in teaching and learning, are both the pros and cons explored, including the risks of form-led assessment processes?

• Is there scope for exploring the ways in which assessment processes change over time and the factors that influence those change?

16 Evidence-based assessment

Two aspects of evidence-based assessment are considered here:

1 learning to identify, gather and use evidence in making assessments

2 the use of evidence to support and evaluate given approaches to assessment.