Differences between coronary disease and stroke in

incidence, case fatality, and risk factors, but few

differences in risk factors for fatal and non-fatal events

Lars Wilhelmsen

1*

, Max Ko

¨ster

2, Per Harmsen

1, and Georg Lappas

11

Section of Preventive Cardiology, The Cardiovascular Institute, Go

¨teborg University, Drakegatan 6, SE-412 50 Go

¨teborg,

Sweden; and

2Centre for Epidemiology, National Board of Health and Welfare, Stockholm, Sweden

Received 15 February 2005; revised 2 June 2005; accepted 16 June 2005

AimsTo compare incidence and mortality of coronary and stroke events, and risk factors for non-fatal and fatal events, respectively.

Methods and results Incidence and mortality were compared in all coronary (n¼559 341) and stroke (n¼530 689) events in Sweden from 1987 to 2001. Data from 28 years of follow-up of a random sample of 7400 men aged 47–55 and free of disease at baseline were used to compare risk factors. Incidence and 28 days of case fatality were considerably higher for coronary disease than for stroke, especially for men. Incidence of coronary disease decreased, especially for men (P¼0.0001 for both sexes), and mortality declined for both men and women during 1987–2001 (P¼0.0001 for both sexes). Stroke incidence declined slightly (P¼0.0001 for both sexes), and there was a decline of mortality (P¼0.0001 for both sexes). Out-of-hospital mortality during the first 28 days was higher than in-hospital mortality for coronary events, whereas for stroke, in-hospital mortality was higher (in men) or the same (in women) as out-of-hospital mortality. High serum cholesterol was a strong risk factor for coronary events, but not for stroke. High blood pressure was a stronger risk factor for stroke. About 50% of men with both stroke and coronary disease died from coronary disease. ConclusionSeveral differences regarding incidence, mortality, prognosis, and risk factors for stroke and coronary disease point towards different pathologies.

KEYWORDS

Coronary disease; Stroke; Incidence; Mortality; Risk factors; Pathology

Introduction

Myocardial infarction and sudden coronary death (in the

fol-lowing denoted as coronary disease) and stroke are common

causes of disability and death and are often discussed as two

diseases of the same family and caused by atherosclerotic

arterial disease. If there were major similarities between

coronary disease and stroke, declining trends in the

inci-dence of coronary disease would be expected also for

stroke. Alternatively, decreasing incidence of coronary

events could lead to risk of stroke in more people.

1If the

two diseases had similar background and pathology, one

would also expect similar risk factors. Elevated serum

cholesterol is a strong risk factor for coronary disease, but

in most prospective studies, it has not been associated

with increased risk for stroke.

2,3However, lipid-lowering

therapy with statins has reduced the incidence of both

thrombotic stroke and coronary disease.

4,5Owing to the suggested similarities of the two diseases

and their great impact on public health, they were analysed

together

in

the

recently

published

SCORE

project.

6The project was forced to restrict the analysis to fatal

events because of differences in criteria for non-fatal

events in the contributing prospective studies. Against this

background, it would be of interest to study further to

what extent risk factors are similar for stroke and coronary

disease and whether risk factors are the same for non-fatal

and fatal events.

In the present paper, we have analysed mortality and

mor-bidity data from the countrywide Swedish Acute Myocardial

Infarction register, which contains data on incidence and

mortality from 1987 until 2001 with a total of 340 721

male and 218 620 female non-fatal and fatal coronary

events. A similar registration of non-fatal and fatal stroke

events included 261 357 male and 269 332 female events.

In addition, data on 28 years of follow-up of 7400 men,

free of these diseases at baseline, were used to compare

risk factors for non-fatal and fatal coronary and stroke

events.

Methods

Registration of events

A national hospital register of diagnoses at discharge has been in operation since 1972 in Sweden and includes all hospitals in the

&

The European Society of Cardiology 2005. All rights reserved. For Permissions, please e-mail: journals.permissions@oupjournals.org*

Corresponding author. Tel:þ46 31 703 1884; fax:þ46 31 703 1890.E-mail address: lars.wilhelmsen@scri.se

doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehi412

by guest on June 6, 2013

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/

country since 1987. The quality of the register during the period 1987–95 has been checked and found to be good.7A file of the

men of the population study described subsequently was also checked against this register and it was found that the register had missed only 3% of hospitalizations for myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation (AF), or heart failure.

The Swedish Causes of Death Register has been operating since 1961 and found to miss only single events. In the present study, record linkage of the Hospital Discharge Register and the Causes of Death Register was performed. An event (non-fatal or fatal) that occurred within 28 days was considered to be the same event and was counted as one event.

In 1987, there was a change from the eighth to the ninth revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) and in 1997, there was a change to ICD-10. These changes were taken into account in the present analyses. The ICD-8 codes were changed to ICD-9.

For coronary disease, ICD-9 code 410 and ICD-10 codes I21 and 22 were used; for stroke, ICD-9 codes 431, 434, and 436 and ICD-10 codes I61, 63, and 64 were used.

Population study of men

The Multifactor Primary Prevention Study was started in Go¨teborg in 1970 and was intended as an intervention trial against smoking, hypercholesterolaemia, and hypertension at pre-defined levels in an intervention group comprising 10 000 men, a random third of all men in the city (n¼30 000) who were born between 1915 and

1925, but not in 1923.8The remaining two-thirds of the population

constituted two control groups of 10 000 men each. A first screening examination took place between 1970 and 1973 and the data from the examination are used in the present study. After 10 years of follow-up, 20% men surviving and still living in the area, according to the population census from the intervention group and one control group, were re-examined. Out of 1805 invited men in the control group, 1473 participated, and of 1803 invited controls, 1404 participated. After these 10 years of follow-up, risk factor values had decreased in the intervention group, but there were no significant differences in serum cholesterol, smoking, and blood pressure, or outcome between the intervention and control groups.8 Thus, any changes brought about by the intervention

took place in the general population as well, as revealed in the ran-domly selected control group, and the present study group is con-sidered to be representative of the background population.

Those men who responded to a postal questionnaire were invited to a screening examination in hospital, in which 7495 men (75% of the sample) took part. The questionnaire contained questions about history of myocardial infarction and stroke among mothers, fathers, and brothers/sisters, previous myocardial infarction, stroke, diabetes mellitus as well as chest pain and dyspnoea on exertion, smoking habits, psychological stress (defined as feeling tense, irritable or filled with anxiety, or having sleeping difficulties as a result of conditions at work or at home during the preceding 1–5 years), and physical activity at work and during leisure time.

Screening examinations were performed in the afternoon. Blood pressure was measured after 5 min rest to the nearest 2 mmHg, with the subjects seated. These afternoon blood pressures were found to be considerably lower when checked later at a more relaxed situation in a subsample; 175/115 mmHg is comparable with 165/95 at resting conditions. Body height was measured to the nearest centimetre and body weight to the nearest 0.1 kg. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2).

Serum cholesterol concentrations (from a sample taken after fasting for at least 2 h) were determined according to standard labo-ratory procedures. Details of the procedures have been published previously.9

The follow-up extended through the year 1998. The endpoints were registered from several sources. Non-fatal and fatal myocar-dial infarction and stroke up to 65 years of age were recorded

according to specific criteria in special registers.10,11The national

hospital discharge register, which included all ages, was also used. For the present analyses, the following principal or contributory diagnoses at hospitalization or death were used:

(i) Non-fatal myocardial infarction (ICD-9 code 410; ICD-10 code I21).

(ii) Death from coronary disease (ICD-9 codes 410, 411, 412, and 414; ICD-10 code I21).

(iii) Non-fatal and fatal stroke (ICD-9 codes 430–434, 436, and ICD-10 codes I60, 61, 63, and 64. I60 (subarachnoidal bleed-ing) was included in this analysis, but not in the national regis-tration of events.

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki rules and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Go¨teborg University.

Statistical methods

Incidence and mortality rates were calculated with the mid-year Swedish population in the respective age groups as denominator. When age-standardization was performed, the Swedish mid-year population of the year 2000 was used as standard. Ages were cate-gorized in 5-year age groups. Differences over time in incidence and mortality were tested with logistic regression. Owing to the large number of events, significant differences are to be expected for some time trends that do not seem impressive. Differences between discrete variables and differences between continuous variables were tested with x2 analysis and t-test, respectively.

Two-sided test withP-values,0.05 are considered as significant.

Results

Incidence, mortality, and case fatality of coronary

disease and stroke in Sweden

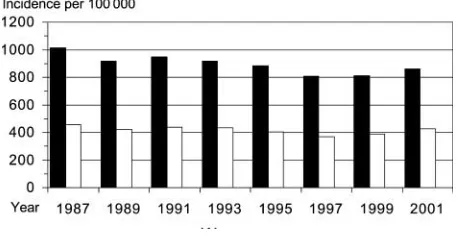

The age-standardized incidence of non-fatal and fatal

myo-cardial infarctions during 1987–2001 among men and women

is shown in

Figure 1.

The incidence was about two times

higher for men compared with women, and there was a

decline in incidence for men from about 1000/100 000 of

the population per year in 1987 to about 800 in 2001

(

P

¼

0.0001); for women, the incidence was around 400/

100 000 and there was a slight decline (

P

¼

0.00021).

There is a slight increase in incidence for 2001, which can

be attributed to change of criteria for myocardial infarction;

elevated levels of plasma troponin T became accepted as

criterion for the diagnosis. The declining incidence among

men was seen for all age groups, except for men aged

.

80. Among men aged

90, the incidence increased (data

Figure 1 Age-standardized incidence of non-fatal and fatal myocardial infarction during 1987–2001 per 100 000 men and women aged between 20 and 90þin Sweden. Decline by time;P¼0.0001 for both sexes.

by guest on June 6, 2013

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/

not shown). For women, the incidence declined between

ages 60 and 84 years, but it increased in the highest age

groups (data not shown).

Mortality from coronary disease declined during the same

period for both men (

P

¼

0.0001) and women (

P

¼

0.0001)

(

Figure 2).

This was evident for all age groups of both men

and women, except those aged

90. These trends reflected

in declining age-standardized case fatality (including deaths

in hospital and outside hospital within 28 days) from 50.5% in

1987 to 33.8% in 2001 among men (

P

¼

0.0001) and from

46.7% in 1987 to 31.9% in 2001 among women (

P

¼

0.0001).

The number of coronary deaths outside hospital exceeded

that of in-hospital deaths, especially for men (all numbers

for mortality within 28 days) (

Figure 3

). During the entire

period of 1987–2001 and for all ages, there were 145 345

deaths within 28 days among men and 61.5% of these

occurred outside hospital. For women, there were 103 484

deaths and 56.3% of these occurred outside hospital.

Incidence and mortality for stroke are shown in

Figures 4

and

5

. The age-standardized incidence was just above 700/

100 000 for men and just above 500/100 000 for women.

Thus, the sex difference for stroke was smaller than that

for coronary disease. For both sexes, there was a

mode-rately declining incidence over the period (

P

¼

0.0001).

The 28 days of case fatality among men declined slightly

from 180/100 000 to just over 160/100 000 from 1987 to

2001 (

P

¼

0.0001) and declined among women from about

145/100 000 to just over 130/100 000 during the same

period (

P

¼

0.0001).

The number of deaths in hospital and outside-hospital from

stroke appears in

Figure 6.

For men, in-hospital deaths were

higher than out-of-hospital deaths for the entire period of

1987–2001, and was about 1.3 times higher than

out-of-hospital deaths. For women, the numbers were similar for

the two types of death.

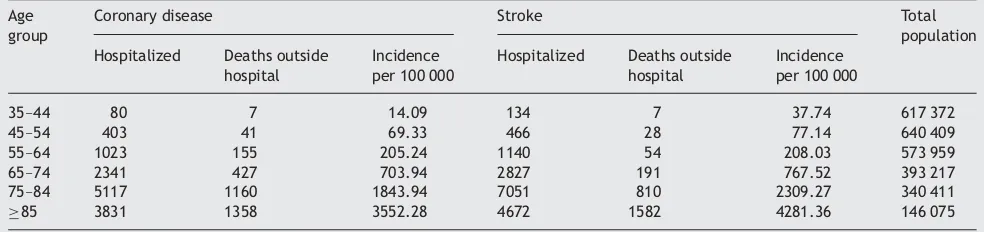

Tables 1

and

2

give the number and incidence for coronary

disease and stroke among men and women per 10-year age

groups during the year 2001 (data available for the last

year). Incidence of coronary disease was higher for men

compared with women for all age groups, with the ratio

4.6 for the age group 35–44 years, declining to 1.5 for the

Figure 2 Age-standardized mortality from coronary disease during 1987–2001 per 100 000 men and women aged between 20 and 90þ in Sweden. Decline by time;P¼0.0001 for both sexes.

Figure 3 Number of men and women died in hospital and outside hospital from coronary disease during 1987–2001 in Sweden.

Figure 4 Age-standardized incidence of stroke during 1987–2001 per 100 000 men and women aged between 20 and 90þin Sweden. Decline by time;P¼0.0001 for both sexes.

Figure 5 Age-standardized mortality from stroke during 1987–2001 per 100 000 men and women aged between 20 and 90þin Sweden. Decline by time;P¼0.0001.

Figure 6 Number of men and women died in hospital and outside hospital from stroke during 1987–2001 in Sweden.

by guest on June 6, 2013

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/

group

.

85 years. For stroke, the men/women ratio was

lower; 1.4 for the lowest age group decreasing to 1.1 for

those aged

85. Thus, for both diagnoses and in all age

groups, the incidence was higher for men than for women.

However, the absolute number of women with strokes was

higher in the two highest age groups because of the higher

number of women in the population in these ages.

Tables 3

and

4

show the case fatality for men and

women, respectively, who died during the first 28 days

from onset and those who died between 29 days and 5

years. The results are based upon the entire period

1987–2001.

The pattern was very similar for men and women; 28 days

case of fatality was about twice as high for coronary disease

(24–75%) compared with stroke (15–44%), whereas case

fatality for stroke tended to be higher for the long-term

follow-up (6–24% for coronary disease vs. 9–44% for stroke).

Thus, for age groups over 55 years, long-term (29 days to 5

Table 3 Male case fatality within 28 days as well as between 29 days and 5 years, respectively, for coronary disease and stroke during 1987–2001 by age group (Centre for Epidemiology, National Board of Health and Welfare, Sweden)

Age

Table 1 Number of men with coronary disease and stroke, respectively, for hospitalized patients and cases died outside hospital, incidence of these events together per 100 000 and total population by age group in the year 2001 (Centre for Epidemiology, National Board of Health and Welfare, Sweden)

35–44 302 121 65.57 193 11 51.31 645 091

45–54 1415 217 273.42 801 41 141.07 596 878

55–64 2970 556 607.36 2221 85 397.21 580 543

65–74 4453 1048 1558.99 4244 241 1271.05 352 857

75–84 6205 1638 3240.59 6526 748 3005.49 242 024

85 2662 916 5366.73 2370 635 4507.27 66 670

Table 2 Number of women with coronary disease and stroke, respectively, for hospitalized patients and cases died outside hospital, incidence of these events together per 100 000 and total population by age group in the year 2001 (Centre for Epidemiology, National Board of Health and Welfare, Sweden)

Age

45–54 403 41 69.33 466 28 77.14 640 409

55–64 1023 155 205.24 1140 54 208.03 573 959

65–74 2341 427 703.94 2827 191 767.52 393 217

75–84 5117 1160 1843.94 7051 810 2309.27 340 411

85 3831 1358 3552.28 4672 1582 4281.36 146 075

Table 4 Female case fatality within 28 days as well as between 29 days and 5 years, respectively, for coronary disease and stroke during the years 1987–2001 by age group (Centre for Epidemiology, National Board of Health and Welfare, Sweden)

years) case fatality from stroke increased to about twice as

high compared with that for coronary disease.

Risk factors for coronary disease and stroke among

men in Go

¨teborg

The original sample of men included 7495 aged between 47

and 55. Myocardial infarction or stroke had occurred before

baseline in 95 men, and 7400 remained for the present

ana-lyses. During up to 28 years of follow-up, 1150 men suffered

primarily non-fatal myocardial infarction and 554 men fatal

coronary disease. Out of the fatal events, 278 (50%) had

diag-noses for myocardial infarction or coronary atherosclerosis.

Primarily non-fatal strokes occurred in 855 men and fatal

events in 150 men. Out of these, 179 men had a diagnosis

of subarachnoidal bleeding or intracerebral bleeding.

Using Cox regression analyses, independent risk factors

for the combination of non-fatal and fatal events have

been published previously

2,12(Harmsen

et al.

has submitted

for publication). Independently significant risk factors for

coronary disease (non-fatal and fatal) during 28 years of

follow-up were age, myocardial infarction in mothers,

fathers, and siblings, chest pain on exercise, diabetes

melli-tus, smoking, low social class, psychological stress, high

serum cholesterol, and high blood pressure (in spite of

treat-ment), but not low physical activity during leisure time or

high BMI.

For stroke (non-fatal and fatal), independent risk factors

were age, previous transient ischaemic attacks, AF, diabetes

mellitus, psychological stress, smoking, high blood pressure,

and high BMI, but not high serum cholesterol or low physical

activity during leisure.

Table 5

lists risk factors that differed

between coronary disease and stroke. Coronary disease and

stroke events during 28 years of follow-up by serum total

cholesterol are shown in

Figure 7.

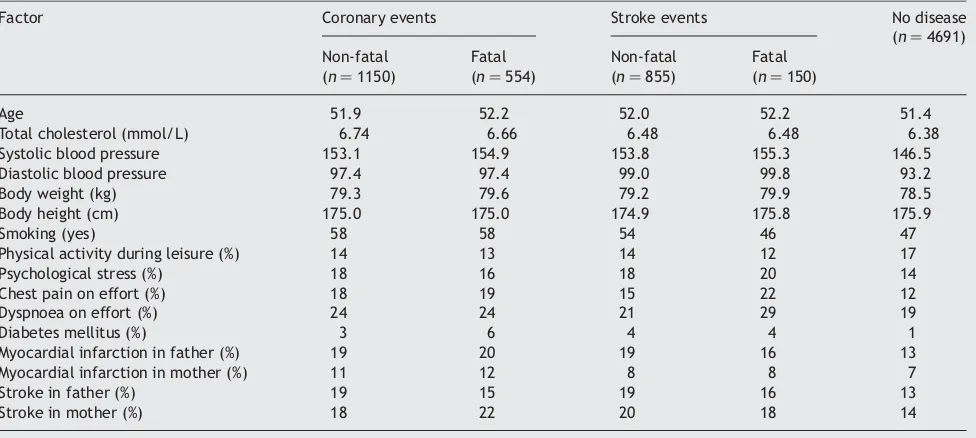

Table 6

gives baseline data for primarily non-fatal and

fatal events within 28 days among those who suffered

coro-nary events and stroke events, respectively, as well as for

those who did not suffer any of these diseases during the

following 28 years. Taking into consideration that multiple

tests were performed, only

P

-values less than 0.01 may

be considered important. Only few differences were

found. Men with fatal coronary events tended to be older

(

P

¼

0.013) and had diabetes more often (

P

¼

0.006). They

tended to have a family history of stroke more often

among mothers (

P

¼

0.036) compared with men who

suf-fered non-fatal events. Men who sufsuf-fered fatal strokes

tended to report chest pain (

P

¼

0.011) and dyspnoea on

effort (

P

¼

0.027) more often than men with non-fatal

strokes, but the baseline age did not differ. None of the

other baseline factors as mentioned in Methods differed

between non-fatal and fatal events for either coronary

disease or stroke.

Out of the 1150 primarily surviving men with coronary

disease, 676 (59%) died during 12 483 person-years of

follow-up. Of these men, 68% died from coronary disease,

5% from stroke, and 27% from other diseases (

Figure 8

).

Out of the 855 surviving men with stroke, 478 (56%) died

during 8315 person-years of follow up. Causes of death

were coronary disease (52%), stroke (13%), and other

causes (35%) (

Figure 8

). Thus, a considerable proportion of

the men with stroke died from coronary disease.

Discussion

When comparing coronary disease and stroke, we found that

incidence and short-term case fatality of coronary disease

were considerably higher than that of stroke, especially

for men. Incidence of coronary disease decreased especially

for men, and mortality declined for both men and women

during 1987–2001. For stroke, there was a less marked

decline regarding incidence and there were slight declines

in mortality. Out-of-hospital mortality during the first 28

days from occurrence was higher than in-hospital mortality

for coronary events, whereas for stroke, in-hospital

mor-tality was higher (in men) or the same (in women) as

out-of-hospital mortality. The 28 days of case fatality from

coronary disease was nearly three times higher for men

and at least two times higher for women compared with

case fatality of stroke during that period. It is known that

a substantial proportion of these early coronary deaths are

instantaneous and are caused by fatal cardiac arrhythmias.

Longer-term (29 days to 5 years) case fatality was higher

for stroke than for coronary disease.

There were well-known differences in risk factors between

coronary disease and stroke: serum cholesterol being a strong

risk factor for coronary events, but not for stroke, not even

Table 5 Differences between coronary disease and stroke forindependent risk factors among men

Factor Coronary disease Stroke

Previous TIA n.s. 1.80 1.19–2.74

AF n.s. 2.55 1.20 – 5.41

A 28 years of follow-up of 7400 men aged 47–55 at baseline. TIA, transitory ischaemic attack; n.s., not significant.

Figure 7 Coronary and stroke events by serum total cholesterol at baseline during 28 years of follow-up of 7322 men free of any of these diseases at baseline.

by guest on June 6, 2013

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/

when only pure thrombotic strokes are analysed, a finding

that is contrary to what was published by Lawlor

et al.

13High blood pressure and high BMI were more important risk

factors for stroke than for coronary events. However,

50%

of both stroke and coronary disease men died from coronary

disease, suggesting similar background pathology for the

two diseases.

The changing incidences for stroke and coronary disease

are of interest. It has been hypothesized that decreasing

coronary incidence might lead to increased stroke incidence

because of the higher number of surviving coronary patients

at risk for stroke. However, death from stroke was not

common among the post-infarct men of the present study.

On the basis of statistical calculations, Peeters

et al.

1denied that increased coronary survival could lead to

increased stroke incidence. The declining coronary

mor-tality is, to some extent, due to the better hospital

treat-ment, but it is noteworthy that out-of-hospital coronary

mortality also declined. The autopsy rate was previously

high, especially among out-of-hospital deaths, and it was

earlier shown that this mortality was mainly caused by

coro-nary disease.

14It has been shown that the declining

coron-ary incidence is primarily due to primcoron-ary preventive

achievements regarding smoking, serum cholesterol, and

blood pressure.

14The previous decline in mean blood

pressure in the population seems to have halted recently,

15and that may be part of the reason for the inconsiderable

decline of stroke incidence. Increased body weight, which

is not of strong importance for coronary disease (yet)

according to our studies,

12but is important for stroke,

16is

another factor that may have played a part. The different

stroke subtypes have different pathological background—

athero-thrombosis vs. haemorrhages. Since 1983, at least

90% of stroke diagnoses were based upon CT scan,

2and

only 18% of the strokes were due to any type of

haemor-rhage. When we analysed risk factors for

thrombotic/occlu-sive strokes separately, we came to the same risk factor

pattern. Thus, athero-thrombotic pathology is the main

background for most stroke events, and the risk factor

difference against coronary disease seems to be due to

differences in pathology for different vascular beds. In

another study, we found increased fibrinogen levels to be

strongly associated with both stroke and coronary disease,

whereas coronary disease, but not stroke, was associated

with high total plasma cholesterol in that study.

17We

studied only men in the present study because comparable

long-term results on risk factors from the same population

and with a great number of events were available. In an

earlier study of women, we found risk factors for coronary

disease to be high serum cholesterol and triglycerides,

smoking, diabetes, as well as high blood pressure, and for

stroke, triglycerides and high blood pressure, but the

number of endpoints was limited to 67 and 66 events.

18Puddu

et al.

19discussed the possible different pathologies

between stroke and coronary disease and concluded that

they are two aspects of the same disease, but that the

Figure 8 Cause of death during follow-up among primarily surviving menwith coronary disease (n¼1150) and stroke (n¼855).

Table 6 Baseline factors for men who suffered primarily non-fatal and fatal coronary disease and stroke, respectively, as well as for men who did not suffer any of these diseases during 28 years of follow-up (Primary Prevention Study, Go¨teborg)

Factor Coronary events Stroke events No disease (n¼4691) Non-fatal

(n¼1150)

Fatal (n¼554)

Non-fatal (n¼855)

Fatal (n¼150)

Age 51.9 52.2 52.0 52.2 51.4

Total cholesterol (mmol/L) 6.74 6.66 6.48 6.48 6.38 Systolic blood pressure 153.1 154.9 153.8 155.3 146.5 Diastolic blood pressure 97.4 97.4 99.0 99.8 93.2 Body weight (kg) 79.3 79.6 79.2 79.9 78.5 Body height (cm) 175.0 175.0 174.9 175.8 175.9

Smoking (yes) 58 58 54 46 47

Physical activity during leisure (%) 14 13 14 12 17

Psychological stress (%) 18 16 18 20 14

Chest pain on effort (%) 18 19 15 22 12

Dyspnoea on effort (%) 24 24 21 29 19

Diabetes mellitus (%) 3 6 4 4 1

Myocardial infarction in father (%) 19 20 19 16 13 Myocardial infarction in mother (%) 11 12 8 8 7

Stroke in father (%) 19 15 19 16 13

Stroke in mother (%) 18 22 20 18 14

P-values for difference between non-fatal and fatal events are given in the text.

by guest on June 6, 2013

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/

reactivity of the coronary and cerebral arteries is different.

Falk

20proposed that the ulceration of atherosclerotic

plaques is important in coronary occlusion, but not in

intra-cranial cerebral arteries. It is also known that individuals

with familial hypercholesterolaemia develop myocardial

infarction at a young age, but they do not develop

stroke.

21The coronary atherosclerotic plaque had higher

lipid content, whereas the cerebral plaque had higher

content of fibrous tissue, which in turn is more strongly

affected by high blood pressure.

22An important practical question is whether the

predic-tions in the SCORE project,

6which was based upon fatal

coro-nary and stroke events, can also be used for non-fatal

disease. In the present analyses, diabetes was a stronger

risk factor for fatal events when compared with non-fatal

events, but diabetes was not included in the SCORE

diagram. Thus, it would not make a difference. A problem

is, however, that out of the three risk factors used in

SCORE, serum cholesterol, blood pressure, and smoking,

there are quantitative differences regarding cholesterol

and blood pressure. In the present study, the relative risk

for coronary events with 1 mmol/L increase of total serum

cholesterol was 1.220, but was insignificant for stroke. The

risks associated with increase of blood pressure were more

similar. Risk for stroke increased with 1.026 and for coronary

with 1.020 for 1 mmHg increase of diastolic blood pressure.

The results regarding coronary events agree with other

pro-spective studies summarized by Dobson

et al.

23When using

SCORE, risk of coronary events are somewhat overestimated

by blood pressure values, but underestimated by serum

cholesterol values, and vice versa for stroke events.

References

1. Peeters A, Bonneux L, Barendregt JJ, Mackenbach JP; Netherlands Epidemiology and Demography Compression of Morbidity Research Group. Improvements in treatment of coronary heart disease and cessa-tion of stroke mortality rate decline.Stroke2003;34:1610–1616. 2. Harmsen P, Rosengren A, Tsipogianni A, Wilhelmsen L. Risk factors for

stroke in a cohort of middle-aged men in Go¨teborg, Sweden. Stroke 1990;21:223–229.

3. Prospective Studies Collaboration. Cholesterol, diastolic blood pressure, and stroke: 13 000 strokes in 450 000 people in 45 prospective cohorts. Lancet1995;346:1647–1653.

4. The Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994;344: 1383–1389.

5. Collins R, Armitage J, Parish S, Sleight P, Peto R; Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. Effects of cholesterol-lowering with simvastatin on stroke and other major vascular events in 20 536 people with cerebrovas-cular disease or other high-risk conditions.Lancet2004;363:757–767.

6. Conroy RM, Pyo¨ra¨la¨ K, Fitzgerald AP, Sans S, Menotti A, deBacker G, De Bacquer D, Ducimitiere P, Jousilahti P, Keil U, Njo¨lstad I, Oganov RG, Thomsen T, Tunstall-Pedoe H, Tverdal A, Wedel H, Whincup P, Wilhelmsen L, Graham IM. On behalf of the SCORE project group. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular risk in Europe: the SCORE project.Eur Heart J2003;24:987–1003.

7. Hammar N, Alfredsson L, Rose´n M, Spetz C-L, Kahan T, Ysberg A-S. A national record linkage to study acute myocardial infarction incidence and case fatality in Sweden.Int J Epidemiol2001;30(Suppl. 1):S30–S33. 8. Wilhelmsen L, Berglund G, Elmfeldt D, Tibblin G, Wedel H, Pennert K, Vedin A, Wilhelmsson C, Werko¨ L. The multifactor primary prevention trial in Go¨teborg, Sweden.Eur Heart J1986;7:279–288.

9. Wilhelmsen L, Rosengren A, Eriksson H, Lappas G. Heart failure in the general population of men—morbidity, risk factors and prognosis. J Intern Med2001;249:253–261.

10. Elmfeldt D, Wilhelmsen L, Tibblin G, Vedin JA, Wilhelmsson C, Bengtsson C. Registration of myocardial infarction in the city of Go¨teborg, Sweden. J Chron Dis1975;28:173–186.

11. Harmsen P, Tibblin G. A stroke register in Go¨teborg, Sweden.Acta Med Scand1972;191:463–470.

12. Wilhelmsen L, Lappas G, Rosengren A. Risk of coronary events by baseline factors during 28 years follow-up and three periods in a random popu-lation sample of men.J Intern Med2004;256:298–307.

13. Lawlor DA, Davey Smith G, Leon DA, Sterne JAC, Ebrahim S. Secular trends in mortality by stroke subtype in the 20th century: a retrospective analysis.Lancet2002;360:1818–1823.

14. Wilhelmsen L, Rosengren A, Johansson S, Lappas G. Coronary heart disease attack rate, incidence and mortality 1975–1994 in Go¨teborg, Sweden.Eur Heart J1997;18:572–581.

15. Wilhjelmsen L. Cardiovascular monitoring of a city during 30 years.Eur Heart J1997;18:1220–1230.

16. Jood K, Jern C, Wilhelmsen L, Rosengren A. Body mass index in mid-life is associated with a first stroke in men: a prospective population study over 28 years.Stroke2004;35:2764–2769.

17. Eriksson H, Wilhelmsen L, Welin L, Sva¨rdsudd K, Tibblin G. 21-year follow-up of CVD and total mortality among men born in 1913. In: Ernst E, Koenig W, Lowe GDO, Meade TW, eds. Fibrinogen: A ‘New’ Cardiovascular Risk Factor.Blackwell-MZV; 1992. p115–119.

18. Rosengren A, Wilhelmsen L, Lappas G, Johansson S. Body mass index, cor-onary heart disease and stroke in Swedish women. A prospective 19-year follow-up in the BEDA study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2003; 10:443–450.

19. Puddu P, Puddu GM, Bastagli L, Massarelli G, Muscari A. Coronary and cer-ebrovascular atherosclerosis: two aspects of the same disease or two different pathologies?Arch Gerontol Geriatr1995;20:15–22.

20. Falk E. Plaque rupture with severe pre-existing stenosis precipitating cor-onary thrombosis: characteristics of corcor-onary atherosclerotic plaques underlying fatal occlusive thrombi.Br Heart J1983;50:127–134. 21. Postiglione A, Nappi A, Brunetti A, Soricelli A, Rubba P, Gnasso A,

Cammisa M, Frusciante V, Cortese C, Salvatore M. Relative protection from cerebral atherosclerosis of young patients with homozygous familial hypercholesteroemia.Atherosclerosis1991;90:23–30.

22. Tanaka K, Masuda J, Imamura T, Sueishi K, Nakashima T, Sakurai I, Shozava T, Hosoda Y, Yoshida Y, Nishiyama Y, Yutani C, Hatano S. A nation-wide study of atherosclerosis in infants, children and young adults in Japan.Atherosclerosis1988;72:143–156.

23. Dobson AJ, Evans A, Ferrario M, Kuulasmaa KA, Moltchanov VA, Sans S, Tunstall-Pedoe H, Tuomilehto JO, Wedel H, Yarnell J. Changes in esti-mated coronary risk in the 1980s: data from 3 populations in the WHO MONICA Project. World Health Organization. Monitoring trends and deter-minants in cardiovascular diseases.Ann Med1998;30:199–205.

by guest on June 6, 2013

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/