The urban land question in Africa: The case of urban land con

fl

icts in

the City of Lusaka, 100 years after its founding

Horman Chitonge

a,*, Orleans Mfune

baCentre for African Studies, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7700, Cape Town, South Africa

bDepartment of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Zambia, P.O Box 32379, Lusaka, Zambia

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 10 September 2014 Received in revised form 9 March 2015

Accepted 27 March 2015 Available online

Keywords:

Urban land conflict Lusaka

Informal settlement Urban planning Land invasion

a b s t r a c t

Pressure on urban land is growing in many cities across Africa and the developing world. This is creating various challenges around urban land administration, planning and development. Growing pressure on urban land is manifesting in various ways including the mounting urban land conflicts. In this paper we look at the urban land question in Lusaka, focussing on urban land conflicts. What we have found in this study is that the reportedly growing invasion of vacant or idle land in Lusaka is a more complex issue which involves not only the desperate urban poor looking for land to squat on, but also well-resourced groups, who sometimes hire poor people to invade the land on which they later develop residential and commercial properties. We argue in the paper that the prevalence of these conflicts points to the gap in the administration, planning and delivery of land and the accompanying services.

©2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

The orthodox land question in Africa has largely focused on the rural land dynamics. In its classical formulation, the land question is strongly (if not entirely) associated with issues of unequal access, distribution, ownership, use and administration of land in rural areas. Urban areas are generally perceived as‘regulated spaces’

where various dimensions of the land question have been effec-tively negotiated through both the market and state intervention. Since the land question has been widely associated with the countryside, there has been little attention in the literature devoted to the different dimensions of the urban land question (Obala& Mattingly, 2013). Debates on issues of land in urban areas are often restricted to matters of planning, housing and informal set-tlement. Rarely are questions about equality of access, ownership and distribution of urban land raised.

But as the pressure on urban land in most African cities builds up, due to the robustly growing population as well as the current episode of sustained economic growth in most countries, the urban land question is resolutely imposing itself on the urban spaces, in various forms such as land invasions. In this paper we look at the

emerging land question in the City of Lusaka (the capital city of Zambia), focussing on one specific way in which the urban land question is manifesting itselfdinformal urban land invasion and

the associated conflicts. In this paper, we show that while the land question in the City of Lusaka is an outcome of the makeshift and lope-sided nature of colonial social engineering, the post-colonial state in Zambia has done little to decolonise both the conception and the structures of urban planning and settlement patterns. In this paper, we define urban land conflicts as social and legal ten-sions manifested in concurrent claims over a piece of land, disputed ownership and other forms of contest around urban land (see Lombard, 2013).

2. Methodology

This paper draws mainly from face-to-face interviews with residents of Mtendere East, conducted in January and July 2014. We also conducted interviews with leaders of different opposition parties, as well as the City of Lusaka officials, including officers from the planning and housing department and the informal settlement unit. In total we interviewed 18 Mtendere East residents, randomly interviewed, since there is no list of residents to sample from. In addition to face-to-face interviews, we also conducted informal conversations with several residents in various sections of the settlement. We also had interviews with two residents of the nearby low density suburb of Ibex Hill who have been living in the *Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: [email protected] (H. Chitonge), omfune@gmail. com,[email protected](O. Mfune).

Contents lists available atScienceDirect

Habitat International

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / h a b i t a t i n t

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.03.012

area before the settlement began. The paper also draws from sec-ondary data and land conflict cases before the courts of law, particularly cases before the Lusaka High Court and the Lands Tribunal.

3. The land question(s) in Africa

The land question in Africa is widely formulated as a by-product of colonial rule on the one hand, and on the other hand, the failure of the post-colonial African states to implement radical land re-forms which would effectively address colonial legacies around land distribution and administration. For some analysts the exis-tence of the land question in Africa today is a reminder of the incomplete process of decolonisation on the continent (Moyo, 2008). In its standard formulation, the land question in Africa is widely conceptualised in terms of inequalities regarding ownership of, access to and control over land in the country side. For instance, it has been argued that, the land question and persistent rural poverty in Africa are fundamentally issues of social justice and equity (Moyo, 2004). This formulation of the land question, how-ever, is more prevalent in southern Africa and some parts of East and North Africa which had large European settler populations during colonial rule, resulting in large scale land dispossession of indigenous African peoples (Moyo, 2008;Mafeje, 2003).

While land access and ownership is also skewed and unequal in most urban areas in Africa, mainstream debates on the land question have often downplayed its urban manifestations (Obala&Mattingly, 2013). There seem to be a widespread assumption that the land question is mute in an urban context. The idea of the land question being a rural matter is implicit in the argument that there has been no land question in Africa except in a few countries with large settler communities such as South Africa, Namibia, Kenya, Algeria and Zimbabwe (Mafeje, 2003). But as some analysts have argued,

To assume that a land question in Africa can only arise out of a particular generic social formation, such as feudal and semi feudal tributary systems of land inequities or widespread settler colonial land expropriation, is to miss the salience of growing land concentration and inequality, and struggles to regain con-trol over land(Moyo, 2004: 1).

If the key element of the land question in Africa is about inequality and injustice in the way land is distributed, accessed, owned and controlled, then the land question cannot be restricted to the countryside only. For instance, in the City of Lusaka, available evidence suggests that more than 70 percent of the city's urban population reside on 10.5 percent of the land in unplanned/ informal settlement while the remaining 30 percent of the popu-lation in planned and conventional suburbs occupy 11.4 percent of the land (LCC, 2000).1

3.1. The urban land question

Thus, if one takes unequal access to and control of land as the core feature of the land question in Africa, then it becomes evident that struggles over access to and use of land are not only a rural phenomenon. There are many, often, inaudible and suppressed struggles over land currently occurring in urban areas among poor urban dwellers (Pithouse, 2014). But often, the urban land struggles and conflicts are obscured by the dominance of the land question in

rural areas, which frequently attract public attention and galvanise wider political alliances (Obala&Mattingly, 2013). Consequently,

… when the land question is reduced to a question of the countryside, or the agrarian questions, the urban land question can also be occluded. And when the urban [land] question is reduced to the housing question, which in turn is reduced to a matter of the number of houses that have been built, without regard for where they have been built, or what form they take, the urban land question is also silenced (Pithouse, 2014).

Although the urban land question has been widely conceived in terms of challenges of squatter settlements and therefore, largely a housing problem; current pressure on urban land is exposing the scandalously unequal distribution of and access to land, which many poor urban dwellers are increasingly becoming aware of. With this growing awareness of the inequality in access to land in urban areas, many landless urban dwellers are inventing ways of making their voices heard, oftentimes through unconventional means such as invasion of either private or public unoccupied or idle land. With little or no hope in the formal land delivery system, the urban poor are more and more,

…bypassing these alien, outdated and inhibitive formal/official urban planning standards and regulations, constantly impro-vising, creating and adopting their own parallel indigenous structures, procedures and institutions in order to tackle their existential problems, chief among which is the provision of shelter/affordable housing (Fekade, 2000: 128).

One of the direct consequences of this scenario is an increase in land conflicts. For instance, the Lusaka City Planning Authority“has reported a rise in the number of complaints that are put before the courts involving allocation and ownership”(SOE, 2007: 29). There are several urban land conflict cases before the Lusaka High Court resulting from illegal occupation of vacant land. One of the most popular cases involves a group of people who invaded and occupied the land near the Libala Water Works. The Lusaka City Council threatened to evict the‘squatters’in 2012, but the group took the matter to court challenging the eviction. There are other cases involving the former Minister of Land who was allocating plots in Lusaka illegally. The case that is similar to the Mtendere East situ-ation is theSakala vs Lutanga Mulakacases, in which the applicant has been living on land belonging to an absentee land lord since the 1970s. When the landlord recently re-surfaced threatening to evict the current occupant, the latter decided to take the matter to court, and the case is still before the Lusaka High Court. In addition to cases before the Lusaka High Court, there are several urban land cases before the Lands Tribunal, which is mandated by the 1995 Land Act to resolve land disputes.

3.2. Dimensions of the urban land question

One of the key dimensions of the urban land question is the struggle to access land among the urban poor, which is often compounded by an inefficient and inequitable land delivery sys-tem. Evidence from Kenya suggests that because of an inefficient land delivery system, a small minority of the urban elite own the larger proportion of urban land (Obala&Mattingly, 2013). Even in cases where flexible land delivery systems such as “occupancy licence”in Zambia,“residence licences”in Tanzania, and“starter tittle and landholder title”in Namibia, exist, not many residents in unplanned settlements have accessed land through these means (Gastorn, 2013).

1 The land usefigures are from the Lusaka Integrated Development Plan (LCC,

The other dimension of urban land question in the case of Lusaka City is the unplanned settlements. Although most of the unplanned settlements have been regularised (officially recognised as legal settlements) and residents are allowed to obtain an occu-pancy licence which is renewable after 30 years, only 12% of the residents have managed to obtain formal documents (LCC, 2000).2 One of the reasons cited for the low up-take of the occupancy licence is that many plot owners in unplanned settlements are scared that once the licence is issued, they will be required to pay regular fees in the form of ground rent, which many cannot afford (Gastorn, 2013). Thus, access to land for most people in unplanned settlements has largely remained outside of the formal land mar-ket. For the City of Lusaka, it is estimated that more than 60% of urban land for new developments is delivered informally due to lack of capacity, inappropriate delivery framework, corruption and backlogs (SOE, 2007). This was confirmed during interviews with the Lusaka City council officials responsible for urban land planning and administration, who acknowledge the lack of capacity and poor land services delivery as enduring challenges.

Another common dimension of the urban land question is the fact that urban land is a closely regulated space, though not always well-planned. Urban land, when compared to rural land, is often under close scrutiny, with several laws regulating the forms of land use, the type of infrastructure, the process of land allocation, forms of validating land ownership, provision of services, expansion etc. Related to this is the fact that urban land is often inscribed and bounded by other land use forms. For example the City of Lusaka in Zambia is bounded by land under traditional authorities on the eastern, south-eastern and northern sides of the city, and by private small agriculture holdings to south. Although the city itself has been expanding in all directions, and in the process transforming the traditional land uses, the sombre reality is that the expansion of the city is limited by thefinite nature of available land on one hand, and the capacity of the urban land planning authorities on the other. The bounded and restricted nature of urban land presents a challenge in terms of planning due to the fact that urban land becomes available as the land use changes from one form to anotherda process which

is often difficult to control and predict especially in cases where the planning authorities have limited capacity and resources.

The third dimension of the urban land question is the compactness of the spaces. The densification of the urban land spaces makes them attractive to many different actors including young adults seeking employment, investors looking for skilled labour, politicians seeking public office, rural dwellers looking for modern amenities. The fourth common feature of the urban land question in developing countries is the increasing pressure from urbanisation (UN Habitat, 2013), especially for countries in Africa which have experienced sustained economic growth for the past decade and half now. This becomes more evident in the case of land in the City of Lusaka.

4. Urban land in Lusaka: A 100-year overview

What is today Lusaka City, started as a railway siding in 1905, meant to provide rest to the workers who were constructing the rail way line from the South (South Africa and Zimbabwe) to the copper mines in the north (present day Copperbelt) (Williams, 1986: 72).3

Prior to the establishment of the railway siding, the area was inhabited by the Soli people, under chief‘Lusaaka’, who lived in scattered villages around the area (Williams, 1986). Within a few years, the railway siding, because of its centrality and geological profile (huge underground water potential), attracted a number of white settlers who in 1913 established the Lusaka Village Man-agement Board (LVMB,Williams, 1986). While the colonial regime imposed strict control on the residence of Africans in urban areas (Collins, 1986), the independence era led to rapid urbanisation mainly as a result of relaxing the urban residence rules, but also the growing demand for labour for the booming copper industry. Abolishment of pass laws and the bourgeoning urban centres attracted many rural dwellers to urban centres to seek the“fruits of independence in town”(Seymour, 1975: 72). However most of the people coming from the rural areas could not find housing in conventional residential areas; because the colonial policy regar-ded the African population in Lusaka as being temporary (Collins, 1986), and therefore did not envision the need for large scale planned settlements for Africans.

Because the urban labour force was regarded as temporary, the responsibility for providing housing (for rent) was considered to rest with the employers. These included the colonial adminis-tration itself, employers who built one room, ‘native huts’

exempt from normal standards of building specified under the public health regulation…(Rakodi, 1986: 199).

This idea that the “towns (and Crown or State Land farming areas) were for Europeans and that the rural were for Africans”

(Collins, 1986: 106), and that urban residence for Africans should be regulated and strictly tied to employment (common during colonial rule in many countries in Southern Africa), influenced the model of planning and development of urban areas including the develop-ment of Lusaka Town. In the case of Lusaka City, the initial 1930 plan by Professor S. D. Ashead (the President of Town Planning Association in the UK), adopted theGarden Citymodel, which was in fashion in the UK, and planned a city for“8000 Europeans and 5000 Africans”(Rakodi, 1986: 199). Although the initial and sub-sequent plans have not been implemented in any meaningful way, the evolution of Lusaka City is haunted by the ghost of the garden city:

Modern Lusaka grapples with the challenges of density, housing, transportation, and infrastructure (among other issues) inheri-ted from the physical layout, segregation, and colonial enfram-ing of original planned city. In this way, the shapenfram-ing of today's squatter settlements around Lusaka e and, indeed, the city's

entire physical formecan be traced back to the beginning of the

relatively young city's colonial history (Gantner, nd).

As noted earlier, the colonial influence on Lusaka's subsequent development is not just in terms of physical planning, but more in the enduring non-physical imprints of the misguided idea of a garden city, and its accompanying planning models, legislation, policy, institutions and administrative structures which have only been partially decolonised.

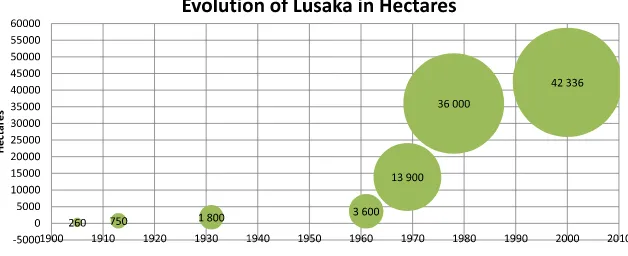

In terms of land size, we see a city that has evolved from a 260-ha settlement in 1905, to a current 36,000 Ha (seeFig. 1).4

Evidence of the evolutionary land map of the City of Lusaka is the massive increase of its land size between 1961 and 1971, 2 The more recent Lusaka City Council Report on theStatus of Unplanned

Settle-ments in Lusaka(LCC, 2006) does not provide the exact number of residents in unplanned settlement who have obtained the occupancy license; it only states the number is estimated to be less than 50 percent.

3 The railway line, which was constructed by John Cecil Rhodes' British South

African Company (BSAC) from Cape Town, reached Lusaka Village in 1905 and the Copperbelt, on the border with Congo, in 1909.

4 The Comprehensive Urban Development Plan adopted in 2007 indicates that

increasing by almost 4 times. This increase can be attributed to population growth due to relaxed residence rules after indepen-dence. For instance, it has been estimated that the total population of Lusaka increased by 230% between 1963 and 1969 from 107,217 to 246,291 (see Collins, 1986: 127; See also Wood, Banda, & Mundende, 1986: 165). This population pressure in subsequent years has forced the city to expand further outwards as shown in Fig. 2.

If we studyFigs. 1 and 2together, it is evident that the city's land is increasingly under pressure from the growing population. The sustained economic growth that Zambia has recorded since the mid-1990 has also contributed to the pressure on the city's land, and Lusaka as the capital city has had a significant share of this growth in terms of commercial and industrial activities. This is evident from the population density which has more than doubled between 1990 and 2010 asTable 1shows.

The population density for Lusaka in 2010 was reported to be 4853.2/km2, which is extremely high compared to other Zambian cities such as Kitwe at 666. 1/km2; Ndola, 409.1/km2; Kabwe, 128.7/ km2and Livingston, 200.7/km2. The increasing pressure on land in Lusaka is partly due to the intra-urban migration which occurred since the 1990s when the Copperbelt experienced low employment due to the privatisation of the mining and related industries. Pressure on the city's land resource is also evident from the number of informal settlement which in 2000 were estimated to be growing at the rate of 12% per year (World Bank, 2002).

AsTable 2shows, in 2010 there were about 37 informal settle-ments in the City of Lusaka, accounting for about 65% of the pop-ulation, occupying just 10% of the city's land. Apart from the a few of these settlements which started as sites and services5 settle-ments during the 1970s, 28 of these settlesettle-ments started as a result of people who could notfind or afford formal housing (SeeCollins, 1986). Due to lack of affordable housing, most of the poor people (mostly new immigrants) had no option but to squat on farm land, rubbish damping areas, quarry land, and on vacant land.

The initial government attitude (immediately after indepen-dence) towards these squatter/unplanned settlements was not different from the colonial approach, which saw these areas as essentially breeding ground for criminals, illegal dealings, disorder, and unemployed urban dwellers with nothing to contribute posi-tively to the development of the city. Thus, the expectation after independence was that these settlements would be eliminated as the country developed (Seymour, 1975). But the failure to cope with the increasing demand for housing in conventionally planned tlements made the government to realise that the unplanned set-tlements were there to stay. Upon realising this, the government

started to find ways of improving the conditions in the

Fig. 1.Evolution of Lusaka in Hectares 1905e2010.

Fig. 2.Population Growth in Lusaka 1964e2010.

5 Sites and services was a policy adopted during the 1970s to improve the living

settlementsdhence the upgrading of informal settlements which

started in the 1970s. The programme of upgrading informal set-tlement in Zambia is reported to be one of the earliest and largest upgrading programmes in Sub-Saharan Africa (World Bank, 2002). There are a number of reasons why the government changed its approach to informal settlements. The most dominant one is the fact that these settlements, because of the high concentration of people, turned out to be the major source of the urban vote (Seymour, 1975). However, there has been ambivalence when it comes to the politics of unplanned settlements (Mulenga, 2003). While successive governments constantly issue threats to demolish any unplanned settlements, opposition politicians (mainly), often

campaign in these areas and promise the residents that their set-tlement would not be demolished once elected into power, and that services such as water, roads, electricity, schools, clinics etc., would be provided (Resnick, 2011).

While most of these settlements have been regularised and gazetted as residential areas, there are still many people whofind it difficult to secure housing in Lusaka, and when these people get a chance, they build shelters on vacant or idle land. In some cases such land occupations are started and encouraged by the dominant party cadres (fervent supporters loyal to a particular political party), especially councillors who sometimes allocate land outside of the city's planning and housing authorities (SOE, 2007). There Table 1

City of Lusaka population profile, 1963e2010.

Year Population Mean annual growth (%)

Share in total national population (%)

Share of total urban population (%)

Number of dwellings

Dwelling growth (%)

Dwelling growth annual (%)

Population density/Km2

1963 195,000 3.5 17.2 27061.0 5416.7

1969 354,000 13.6 6.5 22.0 37675.0 39.2 6.5 2546.8 1974 421,000 3.8 9.0 25.3 79434.0 110.8 22.2 3028.8

1980 535,830 4.5 9.4 21.9 94005.3 18.3 3.1 1488.4

1990 761,064 4.2 10.4 26.5 198254.2 110.9 11.0 2114.1 2000 1,084,703 3.6 11.0 31.7 215316.0 8.6 0.8 3013.1 2010 1,747,152 4.9 13.3 33.8 358871.0 66.7 6.7 4853.2 1963e2010 change (%) 795.9 5.8 281.3 96.3 1226.2 8.4

Source: Author based on data fromCSO (1969, 1980, 1990,2000&2010).

Table 2

Unplanned settlement in Lusaka 2000e2010.

Population Population Households Size (Ha) Legal status Initial Land

2000 2006 2000

Bauleni 19,212 4148

Chainda 10,561 12,841 2484 66.72 Legal 1999 Farm land Chaisa 24,656 29,980 5650 99.81 Legal 1979 Farm land Chawama 52,679 69,405 10 908 115.99 Legal 1988 Workers Compound Chibolya 24,200 25,000 4500 47.32 Legal 1999 Dumping site Chazanga 14,602 17,755 2846 52.62 Not Legal Village land Chipata 29,740 57,039 6364 243.08 Legal 1979 Cropfield Chipata Over Spill 9837 1900

Chipata Site&Services 7333 1344

Chunga 13,878 2608

Freedom 6411 1406

Garden Chilulu 7355 1516

Garden Luangwa 3241 914

Garden Mutonyo 4013 865

Garden Site&Service 3618 716

Gardern Site 4 4811 1130

George 42,680 66,496 9012 248.92 Legal 1976 Farm worker quarters

George Soweto 12,005 2477

Jack 4861 941

John Horward 22,574 27,448 4593 71.52 Legal 1977 Quarry Worker quarters John Leing 38,959 47,371 9249 41.25 Legal 2004 Quarry land

Kabanana/Ngwerere 7652 1436 Kabanana Site&Service 7333 1344

Kalikiliki 11,830 14,384 2517 46.03 Legal 1999 Workers' Compound Kalingalinga 28,686 34,880 5864 68.24 Legal 1986 Farm land Kamanga 7516 9139 1751 52.62 Legal 1999 Farm land

Kuomboka 4401 783

Linda 8203 9974 1843 552.27 Legal 1999 Farm land

Mandevu 16,174 3587 75.2 Legal 1999

Marrapodi 16,432 3433 65.5 Legal 1999

Misisi/Kuku 46,601 56,663 10 832 44.2 Not Legal Farm land Mtendere 50,448 61,341 10 155 209.47 Legal 1967 Reserved Land

New Ng'ombe 4143 927

Ng'ombe 23,850 34,038 5117 93.32 Legal 1999 Cattle Ranch Old Garden 20,348 42,506 4434 387.45 Legal 1999 Farm land Old Kanyama 62,933 103,381 14 812 36.67 Legal 1999 Farm land

New Kanyama 22,089 5183

are newspaper stories almost every week of councillors allocating plots on land which is not designated for housing, especially during election time (Lusaka Times, 2009). At the beginning of 2014, the former PF General Secretary and Minister of Justice, Winter Kabimba, complained during a media briefing about the increasing lawlessness in the allocation of plots in urban areas, and instructed police to deal with anyone, including Patriotic Front(PF) party cadres, who were involved in illegal allocation of plots (Lusaka Times, 2014).

5. Types of urban land conflicts in Lusaka

5.1. Overlapping claims

Urban land conflicts in Lusaka occur in various forms (seeTable 3), though the most common form of land conflicts revolve around the overlapping claims on a piece of land or plot. This often occurs in cases where the land was acquired through an informal market, with two or more people in possession of some document indi-cating that they‘bought’the property or plot. Recently, incidences of concurrent claims are increasingly being reported even on land bought through a formal land market (SOE, 2007). When such conflicts occur, the matter is often reported to the police and the Lusaka City Council Town Planning authorities. Within a 2 hour period when we were conducting interviews in the office of one of the city planning officials, we witnessed three cases of concurrent claims reported by the residents from different parts of the city.

5.2. Land invasion

The other form of land conflict involves invasion of public or private land. This often happens in cases where the land has been idle or undeveloped for some time. In such cases one of the con-tending parties has formal documents as evidence of ownership of the land. The case of Mtendere East, discussed in this paper is one example of such conflicts. Often, conflicts over invaded land involve violent confrontation as the authorities or the title holder seeks to remove the‘invaders’from the land. In a number of cases, struc-tures have been demolished by the police, especially if the invaded land belongs to an influential person with political connections.

5.3. Community protest over land

The other form of urban land conflict that has become a popular occurrence in Lusaka involves public protest of a particular com-munity. In most cases protests arise when the state threatens to demolish the structures which are classified as illegal settlements, either on private or public land. This type of confrontation has been an enduring part of the history of Lusaka from the colonial era, but more pronounced in the post-colonial time when every govern-ment in power attempts to get rid of what it sees as unsightly

settlement (Seymour, 1975). Protests over land also occur when a community in an unplanned settlement is displaced by the city authorities or private title holder to land. Examples of this include the Kampasa case, Garden House, Twin Palm Road and Ibex Hill. The way the conflict is resolved depends largely on the nature of the community. Small and poor communities, often, do not have the capacity to mobilise and sustain the protest to generate the political muscle to ward off the evictions or demolitions (Jere, 2007).

5.4. Boundary disputes

Though not very common in urban areas, disputes over boundaries are becoming a common form of conflict even in urban areas. This involves the contest between the state and other in-stitutions or right holders over a piece of land. In the particular case of Lusaka City, there have been claims of the city encroaching on the land bordering the traditional authorities. While some officials from the Lusaka City Councils as well as opposition parties inter-viewed argued that the land problem in Lusaka is partly because the surrounding traditional leaders are refusing to release land for urban development, there are some who argue that the main issue is lack of the capacity to plan and implement the development and management of land in Lusaka (Simatele&Simatele, 2009.

5.5. Inadequate shelter for the poor

The shortage of low-cost housing units for the poor is also directly related to the urban land question in the City of Lusaka. The problem of housing in Lusaka is one of the important elements of the colonial urban planning legacies and a major source of urban land conflicts. As mentioned above, the colonial planners were highly limited in their perceptions of the housing needs for the African populations (seeCollins, 1986; Williams, 1986). According toCollins (1986), a major defect of urban planning in the colonial era was a failure to recognize the fact that the towns of Northern Rhodesia would require an African populationfive times more than the European population. Due to the shortage of formal housing units after independence, employers began to establish private compounds for their African employees, legally and illegally. These initiatives have formed the nucleus of squatter settlements in Lusaka. Currently, it is not just the unemployed poor that are now facing accommodation challenges in the city, but also those in formal employment, especially new employees who do not have the opportunity to buy houses.

6. Mtendere East case study

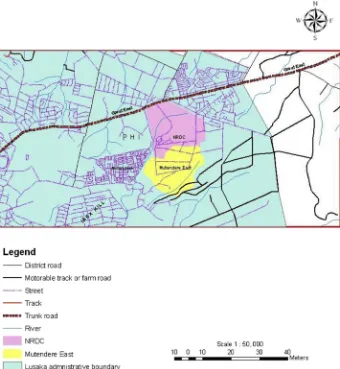

Mtendere East community is located on the eastern side of Lusaka City, bordering Mtendere Compound to the west, Ibex Hill to the south, and the Natural Resource Development College (NRDC) Table 3

Examples of incidences of land conflicts reported in the media between 2013 and 2014.

Name of paper Heading/Conflict issue Date

Lusaka Times Invasion of private landereports that 300 cadres were arrested over invasion of private land in Lusaka West 26thSeptember, 2013

Post Zambia Illegal allocation of landereports that 70% of land in Lusaka is in the hands of illegal ownersecouncillors and

mayors singled out as some of the actors involved in illegal land deals

1stOctober, 2013

Lusaka Times Reports on land mal-administration in Lusaka and the shooting to death of Kapasa residents 18thJune, 2013

Tumfweko Revisits the shooting to death of two Kampasa residents over illegal occupation of land in June, 2013 March, 2014 Zambian Watchdog Reports the violent confrontation between police and over 80 youths over land invasions in Lusaka West.

The confrontations lead to the shooting to death of one youth.

25thMarch, 2014

Lusaka Times Reports the breaking out of riots over the demolition of houses built on illegally acquired plots in Garden House area 26thJuly, 2013.

on the eastern side (seeFig. 3). According to one of the earliest residents in the area, Mtendere East community started some time back in 1991, when a few people invaded the then vacant land belonging to a white absentee landlord who acquired the land during colonial times.6One informant who has been living in the area for a long time now told us that when the invasions started, the building of houses were done at night to avoid attracting attention. As more and more people built houses, the invaders mobilised and fought with police who attempted to demolish the structures. Confrontation with police often resulted in violent en-counters, and in one incident a police officer was killed (Metendere East Interview, 2014). The Mtendere East case is now before the Lusaka High Court, and has not yet been resolved.

While the fact that the case is still before the courts explains why the police are no longer threatening to demolish the houses, there are also reports that some of the police officers and city au-thorities have bought houses and plots in the areas and therefore are not keen to pursue anything that can jeopardise their interests. When we conducted interviews in the area, we noticed that

electricity supply lines have installed in the area, and some resi-dents reported that electricity was provided to certain houses before the matter went to court. When we asked about why the electricity company (ZESCO) decided to provide electricity to a settlement that was declared to be illegal, some respondents mentioned that ZESCO did not care about whether the settlement was legal or not;“all they wanted was money, so they connected us”(Mtendere East Interviews, 2014).

6.1. Reasons for invading the land

During interviews, we could not establish the actual size of the invaded land since no one has official documents, but from the size of the settlement, the land is quite large and the settlement is still growing. Although the initial invaders, mainly from Mtendere Compound, started to build houses during the 1990s, it was only in 2006 when the size of the community grew.

One of our key informants reported that the land was invaded because it was vacant and also because most of the initial invaders were people who could not afford to buy land through the formal land market. As one respondent put it,“I decided to invade land because it is impossible to get land though the normal process which require having sufficient funds in your bank account to support the application for land”(Mtentere East Interviews, 2014). During interviews we discovered that although thefirst group in Fig. 3.Location of Mtendere East settlement.

6 Mtendere East Residents observed that the initial owner of the land (which

the area was from the nearby Mtendere Compound (which also started as an informal settlement), there are now people from different parts of Lusaka who have built or‘bought’houses in the area.

6.2. Status of the settlement

In terms of the law, these plots are still illegal because they are situated on private land which is not gazetted as a residential area. Technically the area is still private land categorised as a farming area and the city authorities have not re-classified the area as res-idential. However, the fact that the land is still not legalised for settlement has not stopped people from buying plots andfinished houses in the area. Most people we spoke to during interviews were of the view that eventually the issues around the legality of the settlement will be resolved and they will be able to get title deeds. Many residents indicated that the two land owners have now stopped pursuing the eviction route; instead they are asking those who have built houses on these plots to pay K15,000 (US$ 3000) for the land. It is not clear if any of the people who have built houses or bought plots in the area have decided to pay the K15,000. Some of the residents we interviewed told us that they are not going to pay; “this land was vacant and idle when we started building, so why should we pay?”(Mtendere East Interviews, 2014).

6.3. Who are the invaders?

From the structures of the houses that have been built in the area, it was apparent that not all the people who invaded land in this area are poor. As one respondent put it,“Not all invaders were poor; some of the invaders include policemen, civil servants, poli-ticians, business men, people working for embassies and many

people in formal employment” (Mtendere East Interviews,

February 2014). The quality of houses being constructed in this area suggests that the people who are building these structures are not the usual poor squatters who often invade land in order to build shacks. The structures that we saw at the time we conducted in-terviews in the area where solid structures built from conventional building materials from walls to roofs, and the plots are well orders (unlike the case of most unplanned settlement in Lusaka where plots are laid out haphazardly). Some of the houses are actually huge with four bed rooms or more, surrounded by a high concrete brick wall-fence. When we further investigated, it became clear that most of the initial invaders were poor people who then sold the plot to relatively well-off people, who are now building the houses.

6.4. Mobilisation

We also asked the residents of this area if they are organised in some form of a social movement or a lobby group to assert the rights on the land they occupy. Most respondents reported that at the beginning they operated as separate individuals without any form of organisation. But later when many people moved into the area, they established some form of structure and elected leaders, who are responsible for mobilising the residents in times of need, such as when the police move in the area threatening to demolish houses. Unfortunately, we could not speak to any of these leaders since most of them were reported to be staying in other suburbs; they only come to the area to inspect their properties.

6.5. Informal urban land market

We also further explored how people sell plots when they do not have titles. Most of the residents we spoke to indicated that

people buy the plots or houses hoping that later the court case will be resolved and they will be able to get a title for their property. While conducting interviews in the area, we were approached by two different men who told us that they could organise a plot for us if we were interested. When we asked them whether we would get a tittle if we bought the plot, one of them said,“Do not worry about the title; that will come later. The important thing is to make sure that you involve neighbours when you are buying”(Mtendere East Interviews, 2014).

Based on the information gathered during fieldwork, it is apparent that a vibrant informal land and property market exists in the area. When we asked residents who have‘bought’or‘own’plots in this area why they paid for a plot without a title, they explained that ordinarily, they would like to buy land on the formal market where they are issued with a title deed, but buying land through the formal process presents several hurdles including the exorbi-tant prices of land in Lusaka. Some indicated that they do not have anything to offer as collateral to enable them access loans from the banks. Some respondents argued that buying land through the formal process involves a lot of corruption such that only connected people manage to get land. While people are aware of the risks of buying land through an informal market, they say that they have no option since the formal land market only favours the well-connected and wealthy people who can navigate the process successfully.

The issues raised in this case touch on the key point raised in the literature about the need to have a moreflexible and responsive urban land tenure system that carters for the different contexts and needs (Payne, 2001;Fekade, 2000; Gastorn, 2013). Evidence from this case study confirms the view that the larger portion of land in Lusaka City (more than 60%) is delivered through the informal markets (SOE, 2007). It is also apparent from this case study that the people in the area have relied on what has been termed the

“numerical strength”to assert their security of tenure (SeePayne, 2001). It is the presence of a large mass which gives them a sense of security, and not a piece of paper (seeFekade, 2000).

6.6. The enduring challenge of the urban land question in Lusaka

If it is true that the invaders are not the poor who are struggling to find adequate shelter, then the Mtendere East case does not address the land question; the poor still remain without access to land and affordable housing. This situation is expected to worsen if the reports that most initial invaders (who were poor) are selling the plots to well-off people from outside the community, are true. What this suggests is that the poor people will continue tofind alternative shelter by invading idle and vacant land, thereby perpetuating the urban land question and conflict. It is only through an innovative andflexible urban land tenure policy and delivery system that the urban land question can be addressed to minimise land conflicts.

7. Causes of the urban land conflict in Lusaka

7.1. Shortage of land

city has run out of land and is in need of more land to avert a land crisis. Although the land use report suggests that there are large tracts of unutilised land within the city's boundaries, what appears as unutilised land has either been earmarked for development or is already under a leasehold title (LCC, 2000). Thus, unless more land is brought under the city's boundary, the land conflicts seen in the past decade are most likely to intensify.

7.2. Vacant, undeveloped, idle land

Existence of vacant and idle land is also cited as one of the factors responsible for the increasing conflicts over land in Lusaka. The existence of land that is not utilised (even if it belongs to someone) when many people are struggling tofind land for shelter encourages land invasions and the emergence of informal settle-ments which often lead to land conflicts. In the case of Mtendere East, the invasions occurred because the land was not being used for a long time and it appeared as though it was abandoned land. The prevalence of idle pieces of land suggests that the city has not been regularly auditing land within its boundaries.

7.3. Poor land delivery system

Conflicts over land in urban areas are also caused by the poor land delivery system as noted above, where 60% of the land is delivered through informal markets. Often the inefficient land de-livery system which involves long waiting periods at every stage of the process from surveying to the issuing of a title, forces people to adopt other means of accessing land including invasions, informal markets and corruption as highlighted in the Mtendere East case. This results in conflicts as the rights in land may not be clearly demarcated through these alternative means. In the context where the value of land is appreciating rapidly due to the increasing de-mand for land (as is the case for Lusaka) an inefficient land delivery system can lead to conflicts due to the failure to allocate and administer land rights and interests properly.

7.4. Political interference of party cadres

One of the most frequently cited causes of urban land conflicts in Lusaka is the issue of party carders and councillors allocating land. All the politicians we interviewed cited what they referred to as cadre-ismas one of the main sources of land conflicts, since the party cadres allocate land outside of approved town planning land use. Not only that, when one political party is voted out of power, the new ruling party comes with its own cadres who begin to re-allocate the plots and this often leads to conflicts. As many re-spondents noted, cadres often allocate land that is already allocated to someone or reserved for a specific use under the city's devel-opment plans. Interviews with the Lusaka City town planning official confirmed that party cadres are a major problem when it comes to implementing the city's urban planning and development policy (Lusaka City Council Interviews, 2014).

7.5. Lack of affordable housing

The shortage of affordable housing in Lusaka and other towns was also frequently mentioned as one of the causes of urban land conflicts since most of the poor who have no access to adequate housing have no alternative but to settle wherever they can. Related to this is the issue of poverty. Most of the poor in urban areas, including Lusaka, cannot afford to build their own houses, and because there are no affordable options for them, they tend to take desperate measures to survive (Simposya, 2010). Almost all the re-spondents indicated that urban land conflicts arise due to the fact

that many poor people see the current urban land tenure as unjust, favouring the rich. Nationally, the urban poor feel left out and the only way for them is take any land that seems idle (Simposya, 2010).

8. Conclusions

It is apparent from the case study presented above that the ur-ban land question has different dimensions. Although the urur-ban land question takes different forms in different contexts, the common origin across cities is the inability of the city authorities to meet the demand for land and housing in a fair and sustainable manner. In the case of the City of Lusaka, the situation is com-pounded by the rapidly growing population and a steadily expanding economy as evident from the population density which doubled between 2000 and 2010 (see Table 1). Inefficient and inadequate planning and development systems in the city make it difficult to respond effectively to the challenges of the urban land question in Lusaka and in other cities. This leads to the emergence and growth of the informal land markets and the associated con-flicts over land. The flourishing of the informal land markets in Lusaka is evidence of the lack of capacity on the part of the city to manage and administer land more effectively. This has resulted not only in the emergence of unplanned settlements all over the city, but also the conflicts over land. Going forward, pressure on land in the City of Lusaka will increase and this will require more effective and long-term planning, to address the looming urban land crisis. This paper has also found that the reported invasion of vacant and idle land in Lusaka is a more complex issue which involves not only the desperate urban poor looking for land to squat on, but involves other well-resourced groups, who sometimes hire in-vaders to invade the land on which they later develop residential properties. However, the reported cases of the initial invaders of land in Mtendere East selling land to well-resourced business people is compounding the urban land question in Lusaka, raising questions about the city's ability to serve the poor sections of the urban society. To address these complex urban land issues, a more flexible and responsive approach to urban land tenure and housing is a prerequisite.

References

Central Statistical Office (CSO,1969). (1969).Census of population and housing. Lusaka: CSO.

Central Statistical Office (CSO,1980). (1980).Census of population and housing. Lusaka: CSO.

Central Statistical Office (CSO,2000). (2000). Census of population and housing. Lusaka: CSO.

Central Statistical Office (CSO,2012). (2010).Census of population and housing. Lusaka: CSO.

Collins, J. (1986). Lusaka: the historical development of a planned capital city, 1931-1970. In G. Williams (Ed.),Lusaka and its environs: A geographical study of a planned capital city in Tropical Africa. Lusaka: The Zambia Geographical Association.

CUDP. (2007).Ministry of local government and housing(MLGH) and Japan interna-tional cooperation agency(JICA). The study on comprehensive urban development plan for the city of Lusaka in the Republic of Zambia. Lusaka: MLGH/JICA.

Fekade, W. (2000). Deficit of formal urban land management and informal response under rapid urban growth, an international perspective.Habitat International, 24, 127e150.

Gantner G., Garden city settlements: The lingering effects of urban design policy in Lusaka, nd, Boston, MASS.

Gastorn, K. (2013). Effectiveness offlexible land tenure in unplanned urban areas in the SADC region: a case study of Tanzania and experiences from Zambia and Namibia.SADC LAW Journal, 3(2), 160e181.

Jere, D. (2007).Homeless zambians face grim winter after demolition. Agence Frencais Presse, 13.5. 2007.

Lombard, M. (2013).Urban land and conflict in the global south.http://citiesmer.wo rdpress.com/2013/04/29/urban-and-conflict-in-global-south (Retrieved 13.05.14).

Lusaka City Council. (2000).Lusaka Integrated Development Planning. Lusaka: LCC.

Lusaka City Council (LCC) and Environmental Council of Zambia (ECZ) (SOE). (2007).

Lusaka City Council (LCC). (2006).A report on the status of unplanned settlements in Lusaka.

Lusaka City Council Interviews. (2014).Interviews with Officials at the Lusaka Civic Centre.

Lusaka Times. (2009).Graveyard refurbished into residential area.http://www.lusaka times.com.

Lusaka Times. (2014).Winter kabimba directs policy tofirmly deal with PF cadres invading private property.http://www.lusakatimes.com.

Mafeje, Archie (2003). The Agrarian question: access to land and peasant response in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Civil Society and Social Movement Programme, Paper No. 6. United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD, 2003).

Moyo, S. (2004).African land question, the state and agrarian transition: Contradic-tions of Neo-liberal land reforms. Available athttp://www.sarpn.org/documents/ d0000692/P763-Moyo_Land_May2004.pdfAccessed 06.03.15.

Moyo, S. (2008).African land questions, agrarian transition and the state: Contra-dictions of the Neo-liberal land reforms. Dakar: CODESRIA.

Mtendere East Interviews( 2014).

Mulenga, C. (2003).Urban slum report: The case of Lusaka Zambia”in understanding slums: case studies for the global report on human setlement 2003(pp. 1e16).

Geneva: UN Habitat.

Obala, L., & Mattingly, M. (2013). Ethnicity, corruption and violence in urban land conflict in Kenya.Urban Studies, 20(10), 1e17.

Payne, G. (2001). Urban land tenure policy options: titles or rights?Habitat Inter-national, 24, 415e429.

Pithouse, R. (2014).The urban land question. Polity.04 April, 2014 availaible atwww. polity.org.za, 12.04.14.

Rakodi, Carole (1986). Colonial urban policy and planning in Northern Rhodesia and its legacy.TWPR, 8(3), 193e217.

Resnick, D. (2011). In the shadow of the city: Africa's urban poor in opposition strongholds.Journal of Modern African Studies, 49(1), 141e166.

Seymour, T. (1975). Squatter settlement and class relations in Zambia.Review of African Political Economy, (3), 71e77.

Simatele, D., & Simatele, M. (2009). Evolution and dynamics of urban poverty in Zambia. In T. Beasley (Ed.),Poverty in Africa(pp. 177e192). Washington, D.C:

Noval Publishers.

Simposya. (2010). Towards a sustainable upgrading of unplanned urban settlements in Zambia. InA Paper Presented at the Conference: Rethinking Emerging Land Markets in Rapidly Growing Southern African Cities, August 31 to November 3rd 2010, Johannesburg.

UN-HABITAT. (2013).The state of the world's cities report 2012/13. Nairobi: UN-HABITAT.

Williams, G. (1986). The early years of the township. In G. Williams (Ed.),Lusaka and its environs: A geographical study of a planned capital city in tropical Africa(pp. 72e94). Lusaka: The Zambia Geographical Association.

Wood, A., Banda, G. P., & Mundende, D. C. (1986). The population of Lusaka. In G. Williams (Ed.),Lusaka and its environs: A geographical study of a planned capital city in tropical Africa(pp. 164e188). Lusaka: The Zambia Geographical Association.