D

EATH

: T

HE

I

MPACT OF THE

S

TATE

,

M

ANAGEMENT AND

C

OMMUNITY AT THE

L

ITHGOW

I

RONWORKS

, 1900–1914

GREGPATMORE*

A

ustralian trade union membership grew dramatically from 1900 to 1914. While there is recognition that compulsory arbitration played an important role, there are a range of factors that may explain the growth. There is also a focus in this debate on unions that grew rather than those that collapsed and a neglect of the workplace in the debate. Through an analysis of the Lithgow Ironworks this paper hopes to broaden the debate about union growth. It attempts to explain why iron and steel unionism arose, briefly collapsed and re-organised at the Ironworks and it focuses on the state, management and community or locality as explanatory factors.INTRODUCTION

While Australian trade union membership grew dramatically in the period from 1900 to 1914, there were examples of unions that did not survive in this favourable climate. Writers concerned with explaining this growth have overlooked examples of union decline and demise in this period. Although the introduction of compulsory arbitration might have played an important role, qualitative and quantitative studies have highlighted a range of factors that may explain the growth and provide insights into why some unions did not survive. Writers also tend to focus on the industry, state and national level rather than the level of the workplace (Bain & Elsheikh 1976: 94–100; Cooper 1996; Markey 1989: 171–2; Patmore 1991: 120–1, 122–6; Sheldon 1995).

Through an analysis of unionism at the Lithgow Ironworks this paper hopes to broaden the debate about union growth in this particular period, and in general. Federal and state governments saw iron and steel as crucial to national development and provided assistance through tariffs and bonuses. The Lithgow plant had operated since 1876, but underwent major capital investment during this period. The Lithgow workers unionised in September 1902 (Patmore 1999; 62–4).1Despite the presence of compulsory arbitration legislation the plant-based union collapsed and workers ultimately joined a union with national coverage. The difficulties of the plant union indicate that compulsory arbitration is an

insufficient explanation for the growth of the Australian trade union movement from 1900 to 1914 and highlight a need to look for other explanatory factors.

The paper presented here begins with an evaluation of the literature concerning trade union membership data and trade union growth. Problems with data on union membership lead to a qualitative rather than quantitative approach. While the union growth literature suggests a range of variables that may explain the experience at Lithgow, this paper examines three factors suggested by the surviving archival sources. These factors are the state, management and community or locality. The paper then provides a narrative history of labour organisation at the Lithgow Ironworks. It finally analyses the impact of the state, management and community or locality on iron and steel unionism at the plant.

DATA AND CONCEPTS

Trade union growth models are only as good as the data on which they are based. Trade union density, which is the number of union members as a percentage of the number of potential members, is the dependent variable in these models. There are two main ways of producing statistics for union membership. One is to obtain estimates from trade union officials. These estimates tend to be inflated by the inclusion of multiple job holders, the unemployed, retired and unfinancials. There are also doubts that the management information systems of unions can provide accurate data due to insufficient resources or minimal interest. Unions may inflate membership to gain greater representation on union peak councils or to create an impression of strength. They may understate membership to reduce affiliation fees. The other way to provide data on union membership is through general surveys of employees. While surveys are viewed as the more accurate method of data collection, errors can arise if the interviewers fail to obtain union status from the retired or unemployed. Defining potential union membership is also difficult. Are employers, the self-employed, the retired and the unemployed to be considered potential union members? Researchers rely on uncertain labour force data to provide a measure of potential union membership (Bain & Price 1980: 6–9; Chaison & Rose 1991: 6–8; Patmore 1992: 225–6; Plowman 1983: 524; Western 1997: 96).

Trade union density data, whether based on trade union reports or on surveys, pose problems for the case study examined in this research. The collection and publication of trade union statistics in Australia was haphazard before the First World War. In Australia, statistics are available from 1891 but they are not totally satisfactory because they relate only to those unions registered with the Colonial and State Registrars of Trade Unions and Friendly Societies. Reliable national figures began in 1912 with the publication of the annual Labour Report. The Australian Bureau of Statistics did not conduct the first employee surveys for trade union membership until 1976. For Australia, the labour force data at both the national and state levels available from 1911 up to the Second World War were based only on the almost decennial census (Bain & Price 1980: ch. 4–5).

or industry levels. Official statistics are not kept for individual workplaces, towns or regions. Although contemporary researchers may be able to undertake surveys at these levels, this option is not available to the historian. Union archives may provide data for particular branches of the union, but it is unlikely that workplace membership data would have been collected or retained. It is more likely that these figures will survive if the union branch corresponded to the workplace or if a particular union only had members in one workplace (Bain & Price 1980: 3; Martin et al.1996: 19–20).

While the absence of detailed data on union membership can prevent quanti-tative analysis, there are still sufficient documents available to undertake a quali-tative study of a workplace. These sources include local newspapers, company records and government archives. They indicate the general trends in union membership and highlight variables that may be significant in explaining the varying fortunes of organised labour in a particular plant.

A range of factors can explain variations in trade union membership. Some relate to macroeconomic variables, such as the level of unemployment. There are structural explanations. The shift in employment away from highly unionised manual sectors, such as manufacturing, towards the poorly organised services sector. The increase in forms of ‘precarious’ employment, such as external contracting and casual labour, has hampered union efforts to recruit new members. Researchers, whether using econometric or non-econometric techniques, disagree over the relative importance of these variables. Chaison and Rose (1991: 36), in their review of the macro-determinants of union growth and density, conclude that structural shifts in employment and public opinion are not primary determinants of union growth at a national level and contribute little to an understanding of international trends. They found that public policy and employer opposition to unionism were important factors in understanding national differences, but recognised that the lines of causation between the two were unclear.

While a range of variables are cited to explain shifts in trade union member-ship, surviving archival sources suggest three factors that may help to explain the levels of unionism in the Lithgow Ironworks: the state; management; and the community or locality.

There has been a long-standing recognition that a sympathetic state may provide a favourable climate for union formation and growth. The state is a ‘locus of power’ which includes a range of institutions such as parliament, statutory authorities, the police, the courts and the military (Garton & McCallum 1996: 117). Western (1997: 66–93, 114, 119–120) claims that the presence of working class political parties in government had a positive impact on union organisation from 1950 to 1990 in 18 capitalist countries. As Bain and Elsheikh (1976: 41) have noted, however, there is a circular argument: union growth is explained by a sympathetic government; a sympathetic government is explained by union growth.

in many ways a product of the system of compulsory arbitration. Some historians have supported this thesis by claiming that compulsory arbitration and wages boards made a major contribution to the growth of Australian trade unions between 1900 and 1914. Econometric models of Australian trade union growth incorporate a dummy variable, which has a value of one in a specified period and zero at other times, for compulsory arbitration to account partially for union growth between 1907 and 1913. Compulsory arbitration required workers to form unions to bring grievances before industrial tribunals. The registered unions gained corporate status and monopoly over organisation in certain industries. There were provisions for a common rule and preference to unionists (Bain & Elsheikh 1976: 40–2; Patmore 1991: 120–1). Even though there was no provision for unionism in the wages board system, some labour historians such as Sutcliffe (1920: 142) have argued that unions grew because workers cooperated to lobby for wages boards, elect representatives, ensure uniform arguments and watch for breaches of awards.

There have been criticisms of the emphasis on compulsory arbitration as an explanation for Australian trade union growth between 1900 and 1914. Arbitration was not a single entity as it varied from state to state and even within states over time in this period. NSW unions perceived the 1908 Industrial Disputes Actas more hostile to their interests than the original 1901 compulsory arbitration legislation. The Australian Workers’ Union and other unions wanted the federal court strengthened to ensure uniform national working conditions, escape inadequate state jurisdictions and benefit from the favourable decisions of Mr Justice Higgins, especially after the Harvester Judgementof 1907 (Patmore 1991: 82, 111). The various econometric studies provide an ad hoc estimate of the impact of arbitration and do not explain the relationship between union growth and arbitration. There is also evidence that some unions collapsed under the strain of the costs associated with arbitration, while registration did not protect unionists from employer victimisation (Cooper 1996: 57–9; Sheldon 1993: 385). Cooper has correctly criticised the ‘dependency thesis’ for ignoring ‘the agency of trade unionist activists in building working class organisation’ and seeing ‘unions instead as mere products of their environment’ (1996: 62).

Critics have argued that other factors, such as the economy and favourable public opinion, provide more significant explanations for union growth in this period. Following the severe depression in the 1890s, there was a brief return to prosperity during 1900–1. However, drought prolonged the stagnation of the economy until 1906. After this there was strong economic growth, which culminated in a boom between 1909 and 1913. In the metals and engineering component of manufacturing, employment doubled between 1905 and 1913 (Markey 1994: 66; Patmore 1991: 141–2). Given the favourable economic climate, union membership would have probably grown anyway without arbitration. Indeed, Sheldon (1998) argues that union activism in a favourable economic climate rather than arbitration underlayed recruitment for four maritime-related unions in NSW from 1900 to 1912.

without the benefit of arbitration. He notes that unions operated in a climate of ‘public sympathy and social conscience’ in the early 1900s, which created a political climate that removed state impediments to unionism and encouraged union growth. Markey also draws parallels with the United States in the 1930s and the introduction of the Wagner Act.

This public sympathy came from several sources. The hardship of the 1890s depression and the significant conflicts between labour and capital during the early 1890s fuelled disillusionment with the market economy and calls for greater state intervention to redress injustices. A group of liberals played an important role in this push for reform. This group included Alfred Deakin, Charles Cameron Kingston, Bernhard Ringrose Wise and Henry Bournes Higgins. They were lawyers who rejected the traditional liberal view that the role of the state should be restricted to maximise the freedom of the individual. These liberals believed the state could facilitate individual freedom by removing the social and economic restrictions on it. They also emphasised the ‘community’ as the overriding social entity, which parliament should protect from the conflicts between labour and capital. The liberals did not seek to end the existing capitalist wage relationship, but wanted to eliminate abuses of that relationship. The major role already played by the state in Australian economic development and labour discipline assisted the liberals’ call for state intervention in labour relations. This public sympathy underlay compulsory arbitration and the broader notion of ‘New Protection’, which linked tariff protection to ‘fair’ wages (Patmore 1991: 101–102, 115).

The attitudes and behaviour of employers towards unions are crucial factors in assisting or hindering trade union growth. Employer attitudes to unions can be influenced by ideology, the economic climate and the legal environment. In recent years, the spread of free market ideologies that view unions as impediments to the successful operation of the labour market have intensified employer’s anti-union activities. Employers can weaken trade anti-unionism through either peaceful competition or forcible opposition. The tactics of peaceful competition include offering better wages than the union standard during a union recruitment campaign, establishing elaborate grievance procedures that exclude unions and encouraging company unions. Forcible opposition includes the victimisation of union activists and discrimination against union members in promotion and pay rises. Employers may also engage in repression to contain the possibility of collective action through the use of measures such as blacklists. They may also defy the law. During the past 30 years US employers have shown an increasing willingness to thwart National Labor Relations Board elections by dismissing trade union activists (Bain 1970: 131–5; Chaison & Rose 1991: 22–4; Freeman 1986: 60–2; Kelly 1998: 56–8; Peetz 1998: 13–15).

than workers in cosmopolitan urban centres. Shorter and Tilly (1974: 238) argued from their study of strikes in France between 1915 and 1935 that that labour agitation was more likely to occur in large diverse cities than in small one-industry towns because workers lived in communities that acquired ‘habits of joint action’. Stromquist (1987) attempted to show that there were differences in response to strikes among the smaller communities. His study of the high level of industrial conflict on the United States railways during the last decades of the 19th century distinguished between ‘market cities’ and ‘railway towns’. He examined Burlington, Iowa, as an example of the former, and Creston, Iowa, as an example of the latter. Burlington preceded railway development and had a broad economic base. Burlington’s elite identified closely with the railway company and its prosperity grew as the railway expanded. Railway workers were dispersed within a larger community and received minimal community support in industrial disputes. Creston relied on the railway for its existence. The town’s elite were retailers, whose prosperity depended on the railway’s freight rates. They were concerned by the company’s monopoly power and sympathised with striking workers, who formed a sizeable group in the town and had consider-able purchasing power. While these basic typologies may be useful for discussion purposes, they overlook evidence that strike action varies among similar types of communities due to differing traditions. Also, ‘community’ as a social construction varies over time and overlooks internal divisions and exclusions (Martin et al.1996: 146–51; Patmore 1994).

The workers’ geographic location, the operation of local labour markets and the local industrial/political traditions can lead to variations in industrial behaviour in specific locations, even where there is the same employer, labour processes, industrial agreement and trade union. Differences in the industrial employment structure between localities are not sufficient to explain spatial differences in strike rates. In areas where there has been a long history of union organisation, a tradition of ‘union culture’ may develop that assists labour organisation and encourages a greater acceptance of unions by local employers. While it should not be assumed that union culture remains unchanged over time or is locally homogeneous (Herod 1998; 24–8; Martin et al. 1993: 55; Martin et al. 1996: 141–51; Wills 1996), locally based traditions, once established, ‘can exhibit a high degree of socio-institutional persistence over time, and, at the very least, influence the nature of subsequent changes and developments’ (Martin, Sunley and Wills, 1996: 16). The spatial organisation of classes in a particular location can also have an impact. Where workers and their employers live in close proximity there may be a greater probability of class alliances or ‘labour-community coalitions’ in dealing with external threats or opportunities (Patmore 1997).

legislation may allow a belligerent employer to defeat organised labour despite local community sympathy (Patmore 2000: 54).

The paper presented here will now examine the impact of the state, employers and the community on unionism in the iron and steel plants at Lithgow. The state, particularly through Labor governments, and the community had a positive impact on Lithgow plant unionism. The benefits of compulsory arbitration appear exaggerated. Lithgow management was not hostile to trade unionism before 1907 and the climate changed with the purchase of the plant by the Hoskins family.

OVERVIEW OF THE IRON AND STEEL PLANT ATLITHGOW, 1900–1914

The iron and steel industry was operating in the Lithgow valley before 1900 but it had a volatile history. Coal and the demand of the NSW Government Railways for iron rails had prompted a group of non-resident entrepreneurs to establish a blast furnace at Lithgow in 1876. However, cheaper imports, high freight charges and poor quality iron ore contributed to financial difficulties and the owners demolished the blast furnace in 1884. The owners initially leased the ironworks to a worker cooperative, which re-rolled rails, and in 1887 transferred the lease to William Sandford. He had experience managing ironworks in the United Kingdom and had come to Australia in 1883 to manage a wire-netting plant for John Lysaght in Melbourne. In 1892, Sandford bought the Ironworks and by 1898 the Lithgow plant employed approximately 200 workers (Patmore 1999: 62).2

From 1900 to 1914 the Lithgow Ironworks underwent major capital invest-ment. Sandford installed a steel furnace in 1900 and re-established a blast furnace in 1907 on the basis of a guaranteed NSW government contract for steel rails. The capital investment in the new blast furnace overextended Sandford’s finances and the Commercial Bank of Sydney foreclosed on him in December 1907. G & C Hoskins Ltd, which manufactured iron pipes in Sydney and was a

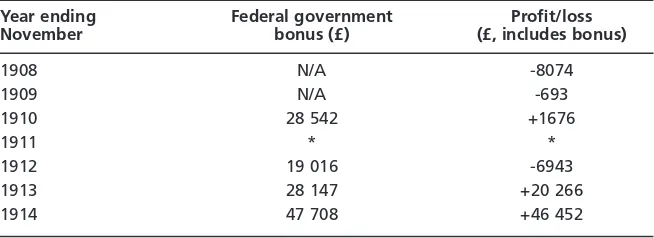

Table 1 Lithgow bonuses and economic performance, 1908–1914

Year ending Federal government Profit/loss November bonus (£) (£, includes bonus)

1908 N/A -8074

1909 N/A -693

1910 28 542 +1676

1911 * *

1912 19 016 -6943

1913 28 147 +20 266

1914 47 708 +46 452

*Data not available.

major customer of the Lithgow Ironworks, purchased the plant. The Hoskins family benefited from the NSW government contract for rails. They also gained from the federal government bounties introduced for steel production in 1909. As shown in Table 1, the Lithgow plant, with the assistance of the bonuses and a booming economy, shifted from losses in 1909 to profits by 1914. The adverse result in 1912 arose from the impact of a prolonged strike and the cancellation of the NSW government contract for rails on the grounds of price and the substi-tution of inferior imported German steel. The improving financial position led Hoskins to complete a second blast furnace in 1913. The expansion of the iron and steel works resulted in a dramatic growth in employment and contributed to Lithgow’s overall population growth. By 1911 the total number of employees at the plant was 1052. The town’s population increased from 5268 in 1901 to 8196 in 1911 (Jack & Cremin 1994: 114–5; Patmore 1999: 62–3).

The Lithgow Ironworks workforce ranged from unskilled labourers to craft workers. While there were sufficient supplies of unskilled labour locally by the early 20th century, Lithgow management found it necessary to recruit overseas to obtain specific ironworking and steel manufacturing skills. In 1900 Sandford directly recruited two Welsh furnacemen to operate his new steel furnace. Between 1905 and 1910 Sandford and Hoskins imported under contract 37 British iron and steelworkers, including blast furnacemen, puddlers and sheet rollers to provide the skills needed for the expansion of the Lithgow plant. There were also skilled tradesmen such as fitters and blacksmiths. They tended to remain members of their own specific unions and formed local branches when there were sufficient numbers. In June 1906, the Amalgamated Society of Engineers formed a Lithgow branch, which had members employed at the Ironworks. The re-establishment of the blast furnace created another dimension to the workforce. These workers held a strategic position in the production process as the blast furnace required continuous operation to avoid considerable expenditure on repairs. Their separate identity from the other ironworkers was reinforced by the blast furnace site being 1 km from the rest of the ironworks (Patmore 2000: 60, 62)3. As will be seen later, blast furnace workers were active in establishing unions at the Lithgow plant.

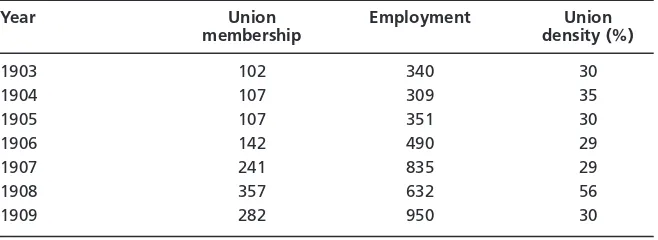

Table 2 Eskbank Ironworkers’ Association membership, 1903–1909

Year Union Employment Union

membership density (%)

1903 102 340 30

1904 107 309 35

1905 107 351 30

1906 142 490 29

1907 241 835 29

1908 357 632 56

As Markey (2002: 37) notes generally, unionisation commenced at the Lithgow Ironworks in the 1880s and was disrupted by the 1890s depression. There was a strong tradition of unionism at the plant. The first Eskbank Ironworkers’ Association had been formed in 1882 and was revived on several subsequent occa-sions before the early 1900s. The Eskbank Ironworkers saw tariff protection as a way to preserve their jobs. As early as July 1885, the union participated in a Sydney conference organised by the NSW Land and Industrial Alliance, which promoted protectionism. The financial problems of the plant hindered the continuity of union organisation. By the start of 1893 approximately two-thirds of the Lithgow Ironworks employees were unemployed and those still with jobs faced a one-third wage-cut during that year. Employment prospects at the Lithgow Ironworks were so poor that some ironworkers migrated to New Zealand to establish a short-lived cooperative at the Onehunga Ironworks near Auckland. The union had again collapsed by early 1894 and did not revive for another 8 years. Unfortunately no records of these early unions survived. However, according the records relating to the union’s affiliation with the Sydney Trades and Labour Council, the number of financial members was only 33 in July 1891, 42 in January 1892 and 25 in July 1892. This would indicate on the basis of surviving employment data a minimum union density varying between 16 and 28 per cent (Patmore 2000: 62; Patmore 2001: 187).4

There were two phases of trade unionism at Lithgow between 1902 and the outbreak of World War I. From 1902 to 1910 the most significant union was the Eskbank Ironworkers’ Association, which changed its name in March 1909 to the Eskbank Iron and Steel Workers’ Association. This union covered only the Lithgow plant and membership figures (Table 2) are derived from its returns to the NSW Registrar of Trade Unions and Friendly Societies for the period from 1903 to 1909. There is a series of employment data available for the plant from 1903 to 1908, which are derived from the Annual Reports of the NSW Department of Mines. However, it is difficult to construct union density data because of inconsistencies. The employment data are expressed as an annual average, while the trade union membership data are shown for 31 December of the particular year. The employment data may include the Lithgow Ironworks Colliery, which was covered by the Western Miners’ Union, and employment data are adjusted where this is explicitly stated. A 1909 employment figure is derived from a company return to the Commonwealth Collector of Customs (Patmore 1999: 63–4).

joint union/management conciliation board to handle grievances, a sliding scale linking wages to product prices and preference to unionists. In June 1904, the union obtained the intervention of the NSW Arbitration Court when it ratified the agreement as an award and provided penalties for breaches. Although there appears to be an increase in union density in 1904, the award and preference to unionists did not provide any permanent basis for growth before 1908 (Patmore 2000: 62).5

The Eskbank Ironworkers’ Association experienced unprecedented growth during 1908 before its eventual collapse by the end of 1910. The success was set against the efforts by Hoskins to make the plant solvent. Worker discontent increased as Hoskins restructured work to reduce labour costs and challenged established customs such as smoking at work. Between March 1908 and April 1909 there were four disputes over wages and work organisation. To increase industrial strength the union began actively recruiting workers at the blast furnace in January 1908. The blast furnace workers had previously attempted to form their own union in October 1907. The Eskbank Ironworkers’ Association refused to accept wage cuts and Hoskins initiated a lockout on 9 July 1908. Full production, with the exception of the bolt shop, did not recommence until 4 November 1908. The union successfully applied for a wages board under the NSW Industrial Disputes Act, which consisted of a judge as chair and an equal number of employee and employer representatives from the Lithgow Ironworks. It obtained a disappointing outcome in March 1909. The award upheld some of Hoskins’s wages cuts and his preference for time-based rates rather than tonnage rates. The award did retain a preference to unionists clause, but this did not prevent a serious decline in membership in 1909. The union was moribund by the end of 1910 despite an attempt by the Sydney NSW Iron Trades Council to revive it in September (Johnston-Liik et al. 1998: 120–8; Patmore 1999: 63; Patmore 2001: 196).6

The second phase of unionism at the Lithgow plant had commenced by at least August 1910 when workers at the blast furnace again formed their own Blast Furnace Workers’ Association. This union, which had only 92 members, decided in January 1911 to expand its coverage of the union by affiliating with the nationally organised Federated Ironworkers’ Association (FIA), thereby gaining access to federal arbitration rather than registering under the unpopularNSW Industrial Disputes Act. The union began actively recruiting other Lithgow iron-workers. This organising ensured the success of the union in the longest dispute in the history of the Lithgow Valley, which occurred at the Lithgow Ironworks from July 1911 to April 1912. It arose from the victimisation of a union delegate at the Lithgow Ironworks Tunnel Colliery. The strike settlement forced Hoskins to reinstate the dismissed delegate. Unfortunately, there is no data series available for union membership at the Lithgow Ironworks after 1909 (Patmore 1999: 64–74).7

ROLE OF THE STATE

While during this period both the federal and NSW governments in Australia introduced compulsory arbitration legislation to regulate industrial relations, it brought mixed blessings for the Lithgow Ironworks workers. The Australian legislation in principle assisted unionisation by assuming that workers would prefer union representation. The 1901 NSW Arbitration allowed registered industrial unions to unilaterally bring employers on any ‘industrial dispute’ or ‘industrial matter’ before a Court of Arbitration. Registered unions gained corporate status and some security against rival unions trying to organise the same workers. The legally enforceable award of the Court could prescribe a minimum rate of wages and preference to unionists. There was also provision for industrial agreements between unions and employers which could have the same effect as a Court award. Bernhard Ringrose Wise, the NSW Attorney-General and architect of the Act, hoped that compulsory arbitration would stimulate and supplement collective bargaining rather than replace it. The Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Act of 1904, which applied to interstate industrial disputes, similarly provided for union registration and preference to unionists (Patmore 1991: 109–110, 115, 125).

The conservative Wade Liberal Reform Government in NSW replaced the expiring 1901 legislation in 1908 with the Industrial Disputes Act. The new law provided for wages boards consisting of a chairman from outside the industry and an equal number of employee and employer representatives drawn from industry. There was an Industrial Court which was presided over by a Supreme or District Court judge. It could recommend to the Minister for Labour the constitution of wages boards and act as a court of final appeal for their decisions. This legislation created an outcry within the NSW trade union movement. Unionists criticised its extensive penal powers for enforcing awards and preventing strikes. They also condemned the legislation for undermining trade unionism, since it allowed associations of at least 20 workers, as well as registered industrial unions, to apply for wages boards. The Labor Council of NSW tried unsuccess-fully to enforce a boycott of the legislation because unions rushed to the Court to prevent rivals obtaining exclusive representation on wages boards and awards (Patmore 1991: 111).

time-based rates. Registration within the industrial arbitration system and preference to unionists in the 1909 award did not prevent the collapse of the Eskbank Ironworkers’ Association in 1910. Through arbitration the state did not assist union survival but appears to have aided union decline and collapse.8

The Lithgow workers benefited from a sympathetic political climate after 1910 with both federal and NSW Labor governments. The Labor Party gained control of Lithgow Municipal Council for the first time on 28 January 1911, winning eight of 12 seats. An important part of Labor Party policy was the nationalisation of monopolies such as the Lithgow Ironworks. During the 1911–12 Lithgow Ironworks strike the Lithgow Council was generally sympathetic to the strikers, authorising a public meeting in Lithgow Park and inspecting strike-breakers’ barracks for breaches of health and housing regulations. The federal and state Labor governments intervened in the strike to Hoskins’s detriment (Patmore 1999: 64–6, 70). From the outset, Labor parliamentarians criticised Hoskins, the NSW Minister for Labor and Industry alleging that he ‘must accept responsibility for this trouble’.9 Hoskins further angered the Labor Party by sending a telegram of support to the NSW Leader of the Opposition during a political crisis, when the Labor Party lost its narrow majority in the Legislative Assembly in late July. The NSW Labor Government failed to resolve the dispute through the establishment of a special wages board and the direct intervention of Premier McGowen and Labor Ministers. Hoskins refused to meet the strikers’ demand that all strike-breakers be removed (Patmore 1999: 69).

The federal and state Labor governments moved against Hoskins. On 30 September 1911, the NSW Attorney-General released John Dixon, the secretary of the Lithgow Branch of the FIA, after 11 days in Darlinghurst goal. He had been sentenced to 2 months hard labour by the Industrial Court for breaching the anti-strike provisions of the 1908 Industrial Disputes Act. The NSW Government also set up a Royal Commission to investigate whether Hoskins’s government contracts were in the public interest and to explore the future prospects of the NSW iron and steel industry. Hoskins criticised the closed hearings of the Commission and walked out of the inquiry in protest at its procedures. The Royal Commission found that Hoskins had breached the govern-ment contracts by substituting German steel for steel made from Australian iron ore and the NSW Government cancelled his contracts on 29 November 1911. The Federal Labor Government also embarrassed Hoskins by investigating his pig iron bonus claims and temporarily suspended the bonus after concluding that he unlawfully had obtained approximately £10 252 in bonus. Charles Hoskins came to believe that the federal and state governments were trying to destroy his firm (Patmore 1999: 68–9).

MANAGEMENT

is no evidence that they victimised union activists. Sandford’s tolerance of the union continued despite his concern over the financial viability of the plant, particularly the construction of a new blast furnace, and his belief that his workers’ wages were too high to survive import competition. Sandford was aware of the growing power of the Labor Party, which he hoped would nationalise the plant and introduce protection to ease his financial worries. Thornley was a long-standing member of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers and had informed Sandford upon his appointment that he was a ‘trade unionist’.10

Hoskins, who purchased the bankrupt Lithgow plant in December 1907, disliked unions and compulsory arbitration. He was an ‘advocate of the open shop, non-union labour and day-wages’ (Wills 1948: 62). Hoskins was hostile to the Labor Party and its policy of nationalising monopolies such as the Lithgow Ironworks. The resignation of Thornley as general manager in April 1908 further reduced the sympathy of the Lithgow plant management for unionism. As noted previously, Charles Hoskins’s efforts to make the Lithgow plant solvent increased worker discontent and contributed to the growth of the Eskbank Ironworkers’ Association in 1908. His lockout in July 1908 failed to defeat the union and led to a fine from the NSW Industrial Court (Patmore 1999: 63, 66–8). 11

Unable to defeat unionism in the public arena, Hoskins intensified his victimisation of union activists. He contributed to the collapse of the Eskbank Ironworkers’ Association by harassing unionists such as Herbert Bladon senior. Bladon had been head roller at the Lithgow Ironworks for about 14 years, served as treasurer of the union and was the worker representative on the wages board. Hoskins believed that Bladon’s mill was over-staffed and threatened Bladon repeatedly with dismissal if he did not keep his mill tidy. Bladon resigned from the Ironworks in August 1908, but remained employee representative on the wages board until he left Lithgow in April 1909. Hoskins also attempted to weaken the fledgling Lithgow branch of the FIA by refusing to re-employ the branch secretary and denying him entry to the plant after a strike at the blast furnace in February 1911. Several other strikers were denied re-employment. Hoskins’s dismissal of a union delegate from the Lithgow Ironworks Tunnel Colliery for attending Western Miners’ Union meeting led to the 1911–12 Lithgow Ironworks strike. During this strike, Hoskins did not discourage strike-breakers from forming their own union, which briefly obtained registra-tion under the NSW Trade Union Act. There are no recorded incidents of victimisation after the strike (Johnston-Liik et al. 1998: 123; Patmore 1999: 66–8, 72).12

COMMUNITY CONTEXT

The Lithgow iron and steel workers enjoyed a supportive community environ-ment. Resistance by landowners at the western end of the Lithgow Valley to the ‘unwarranted expansion’ of Lithgow reduced the availability of land for housing in the town. The local elite could not obtain large plots of land and had to live in close proximity to the workers. There was no pre-industrial elite because the town developed from industrialisation. The town’s business and social elite were concerned with its narrow economic base and the fragility of local industries. They supported the idea that Lithgow would become the ‘Birmingham of Australia’. Lithgow had the potential to become a major manufacturing centre with a significantly larger population. Economic growth would benefit the town’s businesses, increase revenue for the Lithgow Council and improve job security. There was a long tradition of unionism in the Lithgow Valley. Coalminers formed their first lodge in 1875. As noted previously, the first Eskbank Ironworkers’ Association had been formed in 1882. This tradition encouraged the local elite to work with trade union leaders in coalitions to promote the town and be sympa-thetic to workers’ grievances. During the first decade of the 20th century the 8-hour day holiday procession became an important part of the social life in Lithgow with local businesses joining the celebration of labour’s achievements. This union tradition in Lithgow provided a favourable climate for labour organis-ation (Patmore 2000: 56, 62, 66).

The business elite and labour leaders particularly focussed on the iron and steel industry to promote economic prosperity. In February 1904, Lithgow Council agreed to cooperate with the Eskbank Ironworkers’ Association in an approach to the Prime Minister to have a bonus on iron production. When the Commercial Banking Company foreclosed on Sandford’s mortgage and retrenched most of his workers in December 1907, the Lithgow Council, the Eskbank Ironworkers’ Association and Lithgow Progress Association participated in a public meeting and organised a deputation to the Premier (Patmore 2000: 66).

The gap between Hoskins and the local community can be seen in their respective responses to the failure of federal parliament to pass the Bonus Bill in June 1908. Hoskins proposed reductions in wages until the Bill was passed and threatened to shut the blast furnaces and steel furnaces if his employees did not accept the cuts. He latter modified his position by allowing the reductions to be refunded if the Bill was passed. The Eskbank Ironworkers’ Association refused to accept these terms and blamed Hoskins for not being active enough in ensuring the passage of the legislation. A ballot of employees also rejected the wage cuts. Hoskins’ subsequent lockout lasted from 9 July 1908 to 4 November 1908 (Patmore 2001: 196).

during the dispute. With the re-introduction of the Bonus Bill into federal parliament in September 1908, the Mayor of Lithgow called a public meeting to organise a campaign to ensure its passage, which was attended by union repre-sentatives. The meeting established a committee to work in cooperation with the union. This committee provided financial assistance for a union deputation and Ryan to go to Melbourne to lobby parliamentarians by obtaining donations largely from the local business community. In October 1908, the committee and the union jointly produced a four–page pamphlet calling for the passage of a Bonus Bill, which was circulated to federal parliamentarians. The pamphlet claimed that the bonus was necessary to maintain existing wage rates, attract capital investment and create a considerable number of new jobs. The committee also published a union statement supporting the Bonus Bill, which again emphasised the link between the bonus and the maintenance of existing wage rates. This tradition of cooperation clashed with the anti-unionism of Hoskins, who continued to make separate representations to federal parliament until the Bill was finally passed in December 1908 (Patmore 2001: 196–7).

The retailers and professionals were sympathetic to workers during the 1911–12 Ironworks Strike. Prior to the dispute, the local press criticised Charles Hoskins for his hardline approach to industrial relations and his treatment of workers. Lithgow labour and business leaders considered him to be an ‘outsider’, who failed to understand local custom and practice. During the strike, local cinemas held benefit nights. Relief coupons issued by the union defence committee were accepted by 30 retailers and professionals. Towards the end of the strike, the Lithgow Mercury and prominent citizens had joined the call for the nationalisation of the Lithgow Ironworks (Patmore 1999: 67, 70).

CONCLUSION

The paper presented here focuses on the fortunes of trade unionism at the Lithgow Ironworks from 1900 to 1914. In the absence of systematic and reliable quantitative data the study uses documentary sources to explain the varying experience of unionism at the plant. While there may be a variety of causes that explain trade union growth, surviving archival sources required a focus on three issues: state, management and community or locality.

Overall, the state had a positive impact on trade unionism at the Lithgow plant. Labor governments provided a sympathetic political climate for the Lithgow branch of the FIA, particularly during the crucial 1911–12 strike. Labor ministers publicly criticised Hoskins and directly intervened to release the FIA Lithgow Branch secretary from jail. Hoskins was financially weakened by the cancellation of the NSW Government contract.

The experience of the Lithgow plant emphasises the need to look at the impact of management attitudes towards unions on union growth. The Eskbank Ironworkers’ Association was established in a climate of sympathetic management. While there may be questionable motives, such as Sandford’s desire to have the Labor Party ease his financial burdens through nationalisation or protection, Sandford and Thornley persisted with their positive view of unionism at the Lithgow plant despite their financial concerns. Hoskins was unsympathetic and sought to destroy the union through victimisation. Nevertheless, there were limitations on management at Lithgow. During the 1911–12 strike, Hoskins’s attempt to destroy the FIA was thwarted by Labor governments. Indeed, in the wake of the strike, Hoskins became less belligerent towards the FIA as he tried to persuade the NSW Labor Government to nationalise his plant.

Finally, this paper highlights the spatial dimension of trade unionism. The Lithgow plant operated in a community which had a long tradition of labour organisation. This tradition helped union organisation and encouraged even the local elite to see unionism as part of custom and practice. The sympathy of the local elite for workers in Lithgow can also be explained by the land shortages in Lithgow that led them to live in close proximity. While this community support played an important role for the Lithgow workers in public and collective confrontations such as the 1911–12 strike, it was less effective against more individualised and subtle anti-union tactics such as victimisation. Further, while the local struggle for unionism is important, it may not be decisive unless there is a ‘favourable climate’ created by broader political, social and economic factors.

ENDNOTES

1. See also Form A, Trade Union Act 1881, 23.9.02. State Archives Office of NSW, Kingswood 10421/31, file 247.

2. See also Lithgow Mercury, 22.9.1899, 4. 3. See also Lithgow Mercury, 19.6.1906, 2.

4. See also Sydney Trades and Labour Council, General Minutes, 1.2.94. Mitchell Library (ML), Sydney, A3834; Sydney Trades and Labour Council, Sustentation Fund, 1891–2. ML A3850. The only surviving employment data for the Lithgow Ironworks can found in the NSW Department of Mines Annual Reports for 1883, 1885, 1887, 1893 and 1894. Employment for the later 2 years averaged 150, which is the figure used for calculating union density. 5. See also Eskbank Ironworkers v. Sandford, NSW Industrial Arbitration Reports, 3, 1904, 319–22;

Eskbank Ironworkers’ Association, Rules of the Eskbank Ironworkers’ Association, Mercury Newspaper, Lithgow, 1902, 2; Lithgow Mercury, 16.9.1902, 2; 19.12.1902, 4; 6.1.1903, 2; 29.5.1903, 4; 2.6.1903, 2.

6. See also Lithgow Mercury, 17.1.1908, 4; 20.1.08, 2; 13.4.08, 2; 15.3.09, 2. 7. See also Lithgow Mercury, 30.1.1911, 2.

8. Lithgow Mercury, 16.9.1902, 2; 30.1.1911, 2. 9. Lithgow Mercury, 26.7.1911, 2.

10. Lithgow Mercury, 8.4.1902, 2; 2.12.1902, 2; 6.1.1903, 2; 7.4.1903, 2; 22.7.1907, 2; William Sandford, Correspondence and Notebooks, Mitchell Library (ML) MSS 1556/1 Items 4–6, ML MSS 1638/21.

11. See also Lithgow Mercury, 10.4.1908, 4.

REFERENCES

Bain GS (1970) The Growth of White-Collar Unionism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Bain GS, Elsheikh F (1976) Union Growth and the Business Cycle. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Bain GS, Price R (1980) Profiles of Union Growth: A Comparative Statistical Portrait of Eight Countries.

Oxford: Blackwell.

Chaison GN, Rose JB (1991) The macrodeterminants of union growth and decline. In: Strauss G, Gallagher DG , Fiorito J, eds, The State of the Unions, pp. 3–45. Madison: Industrial Relations Research Association.

Cooper R (1996) Making the NSW Union Movement? A Study of the Organising and Recruitment Activities of the NSW Labor Council 1900–10. Sydney: Industrial Relations Research Centre, University of New South Wales.

Ellem B, Shields J (1999) Rethinking ‘regional industrial relations’: Space, place and the social relations of work. The Journal of Industrial Relations41, 536–60.

Freeman R (1986) Why are unions faring poorly in NRLB representation elections? In: Kochan T, ed., Challenges and Choices Facing American Labor, pp. 45–88. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Garton S, McCallum ME (1996) Workers’ welfare: Labour and the welfare state in 20th century Australia and Canada. Labour/Le Travail38 and Labour History71, 116–41.

Herod A (1998) The Spatiality of Labor Unionism. A Review Essay. In: Herod A, ed., Organizing the Landscape. Geographical Perspectives on Labor Unionism, pp. 1–36. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Howard WA (1977) Australian trade unions in the context of union theory. The Journal of Industrial Relations19, 255–73.

Jack I, Cremin A (1994) Australia’s Age of Iron. History and Archaeology. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Johnston-Liik EM, Liik G, Ward RG (1998) A Measure of Greatness. The Origins of the Australian Iron and Steel Industry. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Kelly J (1998) Rethinking Industrial Relations. Mobilization, Collectivism and Long Waves. London: Routledge.

Kerr C, Siegel A (1954) The inter-industry propensity to strike: An international comparison. In: Kornhauser A, Dubin R, Ross AM, eds., Industrial Conflict, pp. 189–212. New York: McGraw Hill.

Markey R (1989) Trade unions, the Labor Party and the introduction of arbitration in New South Wales and the Commonwealth. In: Macintyre S, Mitchell R, eds,Foundations of Arbitration. The Origins and Effects of State Compulsory Arbitration, pp. 156–77. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Markey R (1994) In Case of Oppression. The Life and Times of the Labor Council of New South Wales. Sydney: Pluto Press.

Markey R (2002) Explaining Union Mobilisation in the 1880s and the Early 1900s. Labour History

83, 19–42.

Martin R, Sunley P, Wills J (1993) The geography of trade union decline: Spatial dispersal or regional resilience? Transactions of the Institute of British GeographersNew Series, 18, 36–62. Martin R, Sunley P, Wills J (1996) Union Retreat and the Regions. The Shrinking Landscape of Organized

Labour. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Patmore G (1991) Australian Labour History. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire.

Patmore G (1992) The future of trade unionism: An Australian Perspective. International Journal of Human Resource Management3, 225–46.

Patmore G (1994) Community and Australian Labour History. In: Irving T, ed, Challenges to Labour History, pp. 169–88. Kensington: University of New South Wales Press.

Patmore G (1997) Labour–Community Coalitions and state enterprise: Retrenchment at the Lithgow small arms factory 1918–1932. The Journal of Industrial Relations39, 218–43. Patmore G (1999) Localism and industrial conflict: The 1911–1912 Lithgow ironworks strike

revisited. Labour & Industry10, 57–78.

Patmore G (2000) Localism and Labour: Lithgow 1869–1932. Labour History78, 53–70. Patmore G (2001) The ‘Birmingham of Australia’ and Federation: Lithgow, 1890–1914. In:

Peetz D (1998) Unions in a Contrary World. The Future of the Australian Trade Union Movement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Plowman D (1983) Union Statistics: Scope and Limitations. In: Ford B, Plowman D, eds, Australian Unions. An Industrial Relations Perspective, pp. 522–51. London: Macmillan.

Sheldon P (1993) Arbitration and union growth: Building and construction unions in NSW, 1901–1912. The Journal of Industrial Relations35, 379–397.

Sheldon P (1995) Missing nexus? Union recovery, growth and behaviour during the first decades of arbitration: Towards a revaluation. Australian Historical Studies26, 415–37.

Sheldon P (1998) Compulsory arbitration and union recovery: Maritime-related unions 1900–1912.

The Journal of Industrial Relations40, 422–40.

Shorter E, Tilly C (1974) Strikes in France 1830–1968. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Stromquist S (1987) A Generation of Boomers. The Pattern of Railroad Labor Conflict in

Nineteenth-Century America. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Sutcliffe JT (1920) A History of Trade Unionism in Australia. Melbourne: Macmillan.

Western B (1997) Between Class and Market. Postwar Unionization in the Capitalist Democracies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Wills J (1996) Geographies of trade unionism: translating traditions across space and time. Antipode

28, 352–78.