Business Process Management Journal

A process model of managing organizat ional change during business process redesign Arijit Sikdar Jayashree Payyazhi

Article information:

To cite this document:Arijit Sikdar Jayashree Payyazhi , (2014)," A process model of managing organizational change during business process redesign ", Business Process Management Journal, Vol. 20 Iss 6 pp. 971 - 998 Permanent link t o t his document :

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-02-2013-0020

Downloaded on: 19 March 2017, At : 20: 23 (PT)

Ref erences: t his document cont ains ref erences t o 111 ot her document s. To copy t his document : permissions@emeraldinsight . com

The f ullt ext of t his document has been downloaded 4969 t imes since 2014*

Users who downloaded this article also downloaded:

(2014),"Ten principles of good business process management", Business Process Management Journal, Vol. 20 Iss 4 pp. 530-548 http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-06-2013-0074

(2015),"Integrating the organizational change literature: a model for successful change", Journal of Organizational Change Management, Vol. 28 Iss 2 pp. 234-262 http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/ JOCM-11-2013-0215

Access t o t his document was grant ed t hrough an Emerald subscript ion provided by emerald-srm: 602779 [ ]

For Authors

If you would like t o writ e f or t his, or any ot her Emerald publicat ion, t hen please use our Emerald f or Aut hors service inf ormat ion about how t o choose which publicat ion t o writ e f or and submission guidelines are available f or all. Please visit www. emeraldinsight . com/ aut hors f or more inf ormat ion.

About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com

Emerald is a global publisher linking research and pract ice t o t he benef it of societ y. The company manages a port f olio of more t han 290 j ournals and over 2, 350 books and book series volumes, as well as providing an ext ensive range of online product s and addit ional cust omer resources and services.

Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation.

*Relat ed cont ent and download inf ormat ion correct at t ime of download.

A process model of managing

organizational change during

business process redesign

Arijit Sikdar and Jayashree Payyazhi

Faculty of Business & Management,

University of Wollongong in Dubai, Dubai, UAE

Abstract

Purpose– Business process implementation has been primarily seen as a redesign of the workflow with the consequent organizational change assumed to be taking place automatically or through a process of “muddling through”. Although evidence suggests that 70 per cent of business process reengineering programmes have failed due to lack of alignment with corporate change strategy, the question of alignment of workflow redesign with the organizational change process has not received adequate attention. The purpose of this paper is to provide a framework for managing organizational change in a structured manner during workflow redesign, a perspective missing in the literature on business process management (BPM) implementation.

Design/methodology/approach– This paper attempts to integrate the 8-S dimensions of Higgins model across the different phases of workflow redesign to develop a process framework of managing organizational change during BPM workflow redesign. As an exploratory study the paper draws on existing literature on BPM and change alignment to conceptualize an alignment framework of associated managerial activities involved during different phases of BPM workflow redesign. The framework is evaluated against two case studies of business process implementation to substantiate how lack of alignment leads to failure in BPM implementation.

Findings– The paper provides a conceptual framework of how organizational change should be managed during BPM implementation. The model suggests the sequence of alignment of the 8-S dimensions (Higgins, 2005) with the different phases of the workflow redesign and identifies the role of the managerial levels in the organization in managing the alignment of the 8-S dimensions during business process change.

Practical implications– This framework would provide managers with an execution template of how to achieve alignment of the workflow redesign with the 8-S dimensions thus facilitating effective organizational change during business process implementation.

Originality/value– This paper proposes a process model of how organizational elements should be aligned with the workflow redesign during business process change implementation. No such model is available in BPM literature proposing alignment between hard and soft factors.

Keywords Change management, Strategic alignment, Business process redesign, Process model

Paper type Conceptual paper

1. Introduction

As the basis of competition shifts from cost and quality to flexibility and responsiveness the importance of delivering value through process management has increased significantly. It has been recognized that business process management (BPM) plays a central role in creating sustainable competitive advantage as empirical research suggests positive correlation between process management and business success (McCormack and Johnson, 2001; McCormacket al., 2009; Skerlavajet al., 2007). BPM requires coordinating and integrating cross-functional activities to deliver value to customers (Guha and Kettinger, 1993; Strnadl, 2006). The root of BPM lies in the concept of business process reengineering (BPR) in the 1990s, introduced by Hammer (1990) and Davenport and Short (1990), which advocated a new approach to the

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/1463-7154.htm

Received 16 February 2013 Revised 19 July 2013 6 October 2013 30 November 2013 Accepted 30 January 2014

Business Process Management Journal Vol. 20 No. 6, 2014 pp. 971-998

rEmerald Group Publishing Limited 1463-7154 DOI 10.1108/BPMJ-02-2013-0020

971

Business process

redesign

management of business processes for producing radical improvements in performance. This has led to the replacement of the functional hierarchical perspective of organizing business with the principle of organizing the business as a set of value-adding processes. Examples like Ford’s inefficient accounts payable system with respect to Mazda (Hammer, 1990) and Xerox’s inefficient office systems with respect to Canon (Davenport and Short, 1990) demonstrated how reengineering of business processes as a set of value-adding processes resulted in radical breakthrough in performance.

However, studies have confirmed that 70 per cent of BPR programmes have failed because BPR programmes have not been integrated with the corporate change strategy (Champy, 1995). One reason for this is the overemphasis on the application of information technology (IT) solutions as IT was considered to be a fundamental enabler of process automation in the reengineering programme (Hammer and Champy, 1993; Venkatraman, 1993; Davenport and Short, 1990; Grover et al., 1993) while underemphasizing the soft systems of management (Carr, 2003; Scheepers and Scheepers, 2008; Cooper and Markus, 1995). Though IT has the capability of providing the means to achieve breakthrough performance, according to O’Neill and Sohal (1999) in order to have a full understanding of the effects of reengineering it is necessary to understand the whole business process and how it fits into the organizational system. Evidence from business process implementation suggests that factors like top management support, project champions, communication and inter-departmental cooperation (Ranganathan and Dhaliwal, 2001; Ariyachandra and Frolick, 2008; Bandara et al., 2005) are critical success factors in BPM. As new business process creates a change in the organizational system of relationships, workflows, tasks, structure, etc. so also there is a need to develop an understanding of how the new business process is aligned with the overall organizational system.

The need for alignment of business process with the organizational system is evident from Dooley and Johnson’s (2001) work wherein they observed that New Product Development change efforts were characterized by elements of both reengineering (for alignment with external environment) and continuous quality improvements (for alignment with internal organization). How this alignment is achieved is an important issue in any BPM as successful alignment would facilitate in enhancing the organizational value chain. A survey of international experiences in BPR implementation by Al-Mashari et al. (2001) revealed that organizational experience in integrating change management with BPR implementation is still at its infancy. In this context, the purpose of this paper is to propose a framework to facilitate the alignment of business process redesign with the organizational change efforts during business process redesign implementation.

2. BPM

Hammer and Champy (1993) defines businesses process as “a collection of activities that takes one or more kinds of input and creates an output that is of value to the customer”. BPR, popularized in the 1990s, is considered as the analysis and design of work flows and processes within and between organizations for achieving radical performance improvements (Davenport and Short, 1990). The focus on the narrow technical perspective (Taylorism approach) without giving enough importance to an integrated holistic approach is seen as one of the important reasons behind BPR failures (Al-Mashariet al., 2001). This need for an integrated holistic approach has led to the development of the concept of BPM. The integrated approach of BPM is evident

972

BPMJ

20,6

from the definition of BPM as “supporting business processes using methods, techniques and software to design, enact, control and analyze operational processes involving humans, organizations, applications, documents and other sources of information” (van der Aalst et al., 2003). This integrated perspective of BPM is supported by the distinction between BPM as a holistic management philosophy as against BPR being about radical process redesign (Choong, 2013). Similarly, the holistic perspective of BPM is reflected by Koet al.(2009) representation of BPM as practical, iterative and incremental in fine-tuning business processes as compared to BPR’s focus on radical obliteration of business processes.

2.1 Business process redesign methodologies

Methodology indicates the application of an organized set of methods and techniques to guide a process. According to Barrett (1994), the key to successful process management lies in the development of a vision of the process. The concept of business as a process can be traced to the application of Porter’s (1980) value chain to visualize the business as a combination of core and supporting activities directed towards generating value to achieve the organizational objectives. This modelling is at the macro level of the process and does not give any indication of the linkage between activities and the flow of decision and information. To support business process implementation, various structured methodologies (Klein, 1994; Petrozzo and Stepper, 1994; Furey, 1993; Barrett, 1994) have been proposed. All these methodologies indicate that business process implementation is a stage wise process consisting of certain essential components such as strategizing and goal setting, feasibility analysis, process analysis, understanding customer requirements, performance measurement, designing improvements, prototyping and process mapping and instituting organizational change to implement the new process (Al-Mashari and Zairi, 2000). Similarly, Spanyi (2003) proposed a methodology of business process implementation that called for adoption of eight principles, such as – using customer perspective, awareness of business strategy, creating organizational alignment, creating enabling organization design, using enabling technology, etc. to be followed during business process redesign. As evident, the structured methodologies have recognized the need to institute organizational change/alignment for redesign of the business process. However, these methodologies do not indicate how the organizational change/ alignment are to be instituted. Managing the organizational change requires answer to questions like what specific tasks need to be covered, what should be the timing and sequence, which actors/roles are involved, etc.

The importance of the essential components/principles, as identified in the structured methodologies, in driving the success of business process implementation has been supported in the business process literature. Researchers have found that successful business process implementation requires creating strong linkage between business process and business strategy (Teng et al., 1994; Harvey, 1995) or when the business process architecture enables the organization to link with customer needs (Edwards and Peppard, 1994) or when organizational core competencies are aligned with the business processes (Bhattacharya and Gibbons, 1996). Involvement of different actors is supported by Andreuet al.(1997) framework that link learning at different organizational levels during process innovation. According to Zairi and Sinclair (1995) bottom-up approach to implementation can achieve better performance indicating the importance of the operating people. Also increased acceptance of the business process has been found to be linked to integrating multiple stakeholder

973

Business process

redesign

perspective in the measurement of business process performance (Yen, 2009). Choong (2013) argue that performance measurement system for BPM should focus on the value chain rather than the workflow. All these research highlight the importance of alignment of the business process with the specific organizational elements. However, the research fails to provide answer on how the alignment process is operationalized. For example, in creating strong linkage between business process and business strategy what are the specific tasks, who performs, when, how to manage the impact, etc. are not addressed. Also there is a lack of a comprehensive framework that would align the various organizational elements with the different stages of business process redesign from an end-to-end perspective.

2.2 Business process modelling techniques

A variety of modelling techniques were developed to support process mapping, analysis and design, for example, use of simulation to redesign processes (Ackereet al., 1993). Kettingeret al.(1997) provides a detailed review of the various techniques used in different aspects of BPM like problem solving (fishbone diagram, Pareto diagram), process mapping (process flowchart, role activity diagram, data flow diagram), process measurement (activity based costing, statistical process control), process prototyping (coloured petri nets), etc. In addition to those discussed there exists other modelling tools and techniques that have been developed for business process redesign, a detailed review of each tool is available in Aguilar-Saven (2004). Vergidiset al. (2008) have classified BPM tools and techniques into three categories – mathematical models (facilitating process optimization), diagrammatic models (facilitating graphic representation of the process) and business process languages (facilitating automation of the process design). In addition, BPM standards, like Universal Modeling Language and Business Process Modeling Notation, have been developed to facilitate common language amongst practitioners, academics and IT implementers. In a survey of BPM standards by Koet al.(2009), these BPM standards were classified into the following categories:

(1) graphical standards: this allows users to express business processes and their possible flow and transitions in a diagrammatic way;

(2) execution standards: this computerizes the deployment and automation of business processes; and

(3) interchange standards: this facilitates portability of data, e.g. the portability of business process designs in different graphical standards.

Recent developments in modelling have been related to reusability of business process models for greater efficiency and consistency (Aldin and de Cesare, 2011). This has led the creation of ontologies (semantic models that tend to represent real world systems) like SUPER and BWW for discovering process patterns.

The business process modelling tools and techniques have focused on addressing the operational/technical issues in process redesign to achieve performance improvement (Chang, 1994). The review of BPM standards by Ko (2009) showed their incorporation in various BPM software to support workflow management. This is also supported by Ko et al. (2009) wherein they found that many BPM Suites are actually workflow management systems. Thus, BPM modelling tools and techniques do not throw light on how the process workflow redesign should be aligned with the various organizational soft system elements.

974

BPMJ

20,6

2.3 Business process change management

According to Davenport (1993), successful BPM implementation requires fundamental organizational change in terms of organizational structure, culture and management processes. These changes would impact the human aspect of management as it involves redesignation of work or relationships amongst individuals involved in the execution of the business process. Some authors like Mumford and Beekman (1994) and Bruss and Roos (1993) have suggested that management of organizational change is the largest task in reengineering. Researchers have identified various factors influencing successful implementation of business process change. One such factor is commitment of leadership as it plays a role in providing a clear vision of the future (Hammer and Stanton, 1995; Law and Ngai, 2007). Similarly, empowering employees has been found to be an effective factor for business process redesign implementation success as it promotes self-management and collaborative teamwork (Mumford, 1995). Communication is considered crucial to successful business process implementation (Arendt et al., 1995; Terziovski et al., 2003) as it breaks the barrier between those in charge of the change initiatives and those getting impacted by them. Strategic visioning is necessary to link business processes with potential customers and anticipate future processes (Clemons, 1995) as well as to motivate organizational actors (Carr and Johansson, 1995). Furthermore, it has been identified that factors like organizational structure and inter-departmental interaction (Groveret al., 1999), culture (Willcockset al., 1997)and organizational politics (Boonstra, 2006) play a critical role in successful implementation as they help to manage relationships by promoting trust, openness and resolving conflicts.

However, the business process change management does not provide any guidance on how these various organizational elements are to be incorporated with the stages of workflow design to indicate the sequence of organizational change during business process redesign. This failure to consider the linkages between hard and soft factors has been attributed as the main reason for BPM failures (Trkman, 2010). Thus there exists a distinct knowledge gap in how to integrate the technical perspective of process redesign with the human and strategic perspective of managing organizational change. Table I provides a summary of the knowledge gap that exists in business process implementation.

Main theme Key findings Knowledge gap

Business process redesign methodologies

BPR implementation is a stage wise process consisting of key activities required to design the business process

How to institute organizational change to support the business process? How should the organizational change be managed?

Successful BPR implementation requires alignment with the organization

How to create and manage the alignment?

Business process modelling techniques

Business process workflow can be represented in variety of forms to facilitate optimization and automation

How the business process workflow is aligned with the organizational elements- structure, HR, culture, etc.? Business process

change management

Successful BPM implementation requires fundamental organizational change in terms of organizational structure, culture and management processes

How to link the organizational factors with the process workflow?

How should the organizational factors be implemented?

Table I.

Review of business process implementation literature

975

Business process

redesign

3. Change management and strategic alignment

As indicated in previous sections, organizations that are facing increasing pressure to sustain and surpass competition are required to proactively introduce various change interventions. Depending upon the complexity of the triggers from the internal and external business environment, business leaders may engage in doing things better through incremental improvements within the existing organizational structure and processes or introduce radical and transformational changes usually involving creation of new configurations with regard to systems, structure, process, technology, etc. As is evident, Business process interventions are an example of one such transformational intervention to revitalize organizations in response to stakeholder demands. However, the failure rate of such transformational changes are high because they are high-intensity changes involving substantial changes to existing systems and processes that lead to ambiguity and uncertainty (Beer and Nohria, 2000). This is supported by McNulty and Ferlie’s (2002) study that provided mixed results regarding the outcomes of business process interventions from the health-care sector.

3.1 Implementing change

Beer et al. (1990) provide evidence that while conventional thinking suggests that organization-wide transformational changes is best brought about in a structured manner with leadership support from the top, evidence from organizations that have succeeded in transforming organizations indicate the contrary. Transformational changes that succeeded were brought about through aligning tasks at a unit level or departmental level which were then spread across the organization in an integrated and aligned manner through a bottom-up approach. This was achieved by first creating a critical mass at the operational level through engaging them in problem-solving thereby proactively changing assumptions and mobilizing commitment, and then providing the necessary support to develop new competencies and finally modifying structures, performance management and reward systems to sustain the continued effectiveness of newly articulated roles and responsibilities, and then spreading this change to an organization-wide level. The holistic approach and bottoms-up engagement is strengthened by having transformational leaders who demonstrate sustained commitment throughout the change process through their rhetoric, actions and decisions. Support for a holistic approach to change management comes from Beer and Nohria (2000) who advocate combining a top-down economic approach (with a focus on modifying structures and systems in a directive manner to create shareholder value) with a bottom-up organizational development approach (focused on changing the deep rooted assumptions and thus the organizational culture through various human related interventions aimed at building employee capabilities) for transformational changes to succeed. Adcroft et al. (2008) further propose that irrespective of whether the approach to change is top-down or bottoms up, it must proceed in an integrated manner with an accurate diagnoses of why change is required and an informed analyses of the desired outcomes with active engagement of key stakeholders across all levels during all stages of the transformation process.

Operationalization of this holistic approach is informed by various process models of change which offer useful insights on how to navigate the complexities of the change process in a step-wise and integrated manner. The foundations for much of change research and specifically the process models which advocate a planned approach have been laid by the three-step process model of change by Kurt Lewin which proposed

976

BPMJ

20,6

that unfreezing of current state is fundamental before implementing the change itself and refreezing new changed behaviours and skills with supportive institutional mechanisms are necessary to sustain transformational changes (Lewin, 1951; Burnes, 2004a, b). Hayes and Hyde’s (1998) generic process model of change likewise proposes that before introducing any transformational change, one must first identify the external and internal triggers for change and make it explicit to create awareness regarding the need for change. They propose that one must then convert this need into a desire for change through engaging key stakeholders in accurate diagnoses of internal and external alignment factors which would create a sense of urgency which must then be channelized through appropriate planning such as through setting timelines, allocating resources and identifying change agents concluding with a review of the change process to spread and sustain good practices.

Much of this research has recognized that at the heart of this holistic and integrated change management approach lies the various people related concerns that must be proactively addressed through stake-holder management, leadership, communication and motivation. For example, Armenakis and Harris (2002) propose that in order to create change readiness the content of communication must provide evidence to key stakeholders regarding the discrepancy between existing state and desired state. In addition, the change must be perceived as appropriate and this can be achieved through engaging key stakeholders in diagnoses and problem-solving which also enhances their sense of control over the outcome. According to Armenakis and Harris (2002), this increased self-efficacy enhances change readiness which is further strengthened by perceptions of support from senior management with regard to information and resources, a finding supported by Fugateet al.(2012) who also found that fairness in decisions as evidenced through procedural, distributive and interactional justice played a major role in reducing perceptions of threat during periods of change, thereby decreasing resistance. The role of leadership and various organizational socialization strategies in bringing about changes in deep-rooted assumptions thereby facilitating transformational change has been recognized in much of change literature (Taormina, 2008; Beer and Nohria, 2000; Burke and Litwin, 1992; Kuhlet al., 2005). Kotter’s (1995) eight step model of transformational leadership suggests that for transformational changes to succeed, leaders have to play a crucial role in establishing a sense of urgency by unfreezing assumptions, forming a powerful guiding coalition, creating and communicating a compelling vision, empowering change recipients to act through creating facilitating organizational systems, and then consolidating and institutionalizing the change. Research also proposes the need to address change readiness at individual, group and organizational levels because their antecedents and consequences are different further suggesting that both affective and cognitive components of change readiness must be addressed while using different styles of communication to address emotional vs cognitive needs of change recipients (Raffertyet al., 2013; Jick, 2003). For example, there is evidence in literature to suggest that the change message itself may be conveyed using different techniques, depending upon the stage of the change process and the maturity and information requirements of change recipients. These techniques may include direct communication through verbal messages or selling the message with an intention to persuade, proactive sharing of information with key stakeholders, consensus-building through engaging change recipients in discussion and problem-solving and provision of relevant information from internal and external sources (Armenakis and Harris, 2002; Jawahare and McLaughlin, 2001).

977

Business process

redesign

3.2 Alignment in change implementation

It is evident from the aforementioned literature on change management that the sustained success of transformational changes are impacted by the extent to which those leading the change are taking a holistic and integrated approach with a focus on both the hard factors such as structure, systems, technology, processes and the softer issues, such as people and culture.

Close strategic linkage between competitive strategy and the operations function is also crucial (Rhee and Mehra, 2006). Particularly significant for operationalizing this holistic approach is an understanding of internal or external fit or the process of alignment that emerges from the open systems view of organizations which proposes that changes to any one element of an organization will have an equal impact on other elements. The implication therefore is that any change whether it is transactional or transformational will fail if internal and external alignment issues are not addressed in a timely manner. Various diagnostic models of change have been proposed in literature which informs practitioners on how to achieve this alignment. For example, Nadler and Tushman’s (1980) congruence model proposes that organizations are dynamic entities and organizational effectiveness can only be achieved if changes to the various internal elements such as the task that comprise the various activities of the organization, skills and competencies of people, structural and social dimensions, both formal and informal are informed by the organizations’ strategic goals which itself must be informed by external contingencies. Furthermore it is proposed that the extent of fit or alignment between these internal components determines the success of change efforts which in turn thus impact organizational performance. Other models of internal alignment echo a similar view in that effectiveness of an organization is impacted by the degree of fit that exists between strategy, structure and systems, culture, skills and resources (Kotter, 1980).

While much of the literature on alignment recognizes the significance of fit in internal elements, it is also recognized that tightly coupled systems (as evidenced by strong fit between internal elements) are at risk of decreased adaptiveness. It is thus recommended that in order to remain competitive, organizations must develop robust systems and processes by which environmental changes can be detected and addressed proactively such that incremental changes can be brought about within the internal configurations to continuously align with changes in the external environment (Siggelkow, 2001). A very useful model for diagnosing both internal and external alignment has been provided by Burke and Litwin (1992) who propose that transformational changes that are mostly driven by extreme and often unexpected pressures from the external environment require creation of new configurations or doing different things which can only be achieved if changes are brought to the fundamental elements of the organization such as organizational cultures defined by deep-rooted values along with transformational leadership and changes to organizational strategy itself. Changes in these key elements will then impact and inform lower-order elements including the structure, human resource (HR) practices and policies, tasks and roles, all of which when in alignment will lead to transformational changes across the organization. However, transactional changes intended to modify existing systems or behaviours would only require interventions at the unit, or departmental level and can be managed through project management delegated to key people at the unit level. Thus this model offers useful insights to change leaders with regard to the focus and scope of changes (Burke and Litwin, 1992).

978

BPMJ

20,6

Schneideret al.(2003) provide further evidence that in organizations whose strategic goal is that of service excellence, one can find a constant reciprocal and synergistic relationship between strategic direction, HR practices and organizational culture such that all actions are integrated with each other thus reinforcing the message of service excellence. Buch and Wetzel (2001) suggest that alignment of culture with strategy can be brought about through engaging organizational incumbents in a reflection on existing culture, followed by active data collection and documentation of misalignments between structure, culture, HR practices and systems. These gaps may then be resolved through short term, intermediate or long-term change interventions to strategy, structure, people, process or systems depending upon the extent of discrepancy between desired culture and existing culture (Buch and Wetzel, 2001). Higgins’s 8-S model of strategic alignment likewise provides a very useful model to inform practitioners on how to achieve cross-functional alignment for enhancing strategic performance (Higgins, 2005). Higgins proposes that “at a minimum, executives must align the following cross-functional organizational factors – structure, systems and processes, leadership style, staff, resources, and shared values – with each new strategy that arises in order for that strategy to succeed, in order for strategic performance to occur” (Higgins, 2005, p. 4).

The significance of this holistic approach in implementing Business Process Change is also being increasingly recognized in BPM literature. Failure to align people and organizational culture is recognized as one of the key barriers with regard to transforming organizations from a silo-based functional culture to a process-based culture and systemic thinking underlying BPM as this requires cross-functional integration (Segatto et al., 2013; da Silva et al., 2012; Crawford and Pollack, 2004). Palmberg (2010) provides evidence collected through a multiple-case study approach that movement from a pure functional to a completely process-based structure puts substantial pressure on employees because of the increased accountability required of them, which in turn acts as a barrier to BPM implementation. A combined soft and hard approach to BPM is thus advocated, wherein key roles such as that of process owners and process improvement teams and steering committees be designated at all stages of the change process with clear responsibilities, accountabilities and sufficient power; followed by focusing on the hard aspects, by taking a structured approach focusing only on those processes that are critical for the accomplishment of the organization’s strategic priorities (Siriram, 2012; Palmberg, 2010). Further support for the significance of change management during BPM comes from a Project Alignment Model proposed by Box and Platts (2005) which recognizes the significance of both internal and external alignment for project implementation to succeed. This model also recognizes the significance of empowered, engaged, committed and competent project leaders distributed across the organization with clear project related accountabilities and an organizational culture characterized by a collaborative ethos essential for building a readiness for change.

It is evident from the aforementioned literature that the success of techno-structural interventions such as business process redesign would depend on taking a holistic and integrated approach with particular emphasis on fit or alignment with HR practices and strategic deliverables. As BPR encompasses transformational change elements which impact the organization in totality, therefore piece-meal and compartmentalized approaches to bring about this change will not have any sustainable impact on organizational improvement. Empirical evidence suggest that BPM efforts have failed due to lack of alignment with organizational culture and HR systems and practices,

979

Business process

redesign

rigid hierarchical structures and managers with low competence and commitment (Appelbaum and Lee, 2000; Groveret al.1995) which signifies the central role played by alignment in business process change. In view of the importance of change management in BPM interventions, Kettinger and Grover (1995) have highlighted the need for integration of process management and change management in their theoretical framework of business process change management.

While literature does provide evidence that transformational changes such as business process redesign fail due to a compartmentalized approach to change and inadequate attention to alignment issues, no studies have as yet provided any practical tool to map the process of technical implementation while achieving alignment at strategic, cultural and structural level.

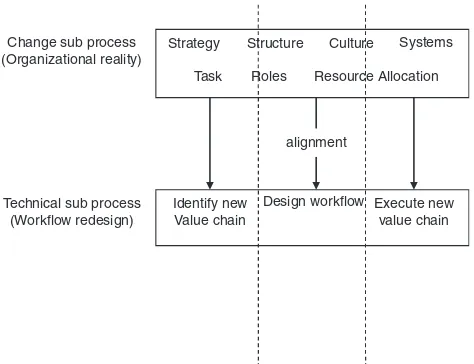

4. Achieving alignment during BPM: an operational framework 4.1 Alignment of technical and change sub-processes

The nature of business process redesign indicates a change in the way things are going to be done within the organization in the future. This change not only impacts the technical dimension but also the human dimension of behaviour and interaction (Al-Mashari and Zairi, 2000). Every existing organization has its organizational reality represented by assumptions and beliefs of the individuals and groups in the organization (Van Maanen and Schein, 1979; Weick, 1995) and any change process creates a new organizational reality as existing assumptions and beliefs are altered. Business process redesign being a change process, is supposed to bring about a new organizational reality and thus it is necessary for BPM implementation to understand the existing organizational reality in order to chart a way for the creation of the new organizational reality. Thus any BPM implementation would involve an organizational change sub process running alongside the technical (workflow redesign) sub process (Figure 1). According to Weick’s (1988) enactment theory, people enact limitations upon the system to avoid issues and thus the existing organizational reality will be enacted to avoid implementing the redesigned process. Overcoming this would require creating the new organizational reality to align with the redesigned business process in BPM.

Change sub process (Organizational reality)

Technical sub process (Workflow redesign)

Strategy Structure Culture Systems

Task Roles Resource Allocation

Identify new Value chain

Design workflow Execute new value chain alignment

Figure 1.

Alignment in BPM

980

BPMJ

20,6

The need for alignment between the BPM technical process and the new organizational reality raises important questions about how this alignment needs to be performed. What is the role of the different levels of management in the process of alignment? What activities of alignment need to be performed during the stages of BPM implementation? What should be the sequence of activities for alignment? Answers to these questions would provide managers a practical guide on how to integrate the technical perspective of BPR with the human perspective of managing organizational change.

4.2 Developing the alignment framework

The methodology followed for developing the alignment framework is based on the theory of pattern matching and is more applicable for complex situations (Trochim, 1989). Pattern matching always involves an attempt to link two patterns where one is a theoretical pattern and the other is an observed or operational one. In this case the theoretical pattern is represented by the change management alignment theories wherein it is hypothesized that alignment of organizational elements leads to performance improvement. Since BPM involves a change in organizational practice it could be hypothesized that performance improvement is possible when there is organizational alignment. The observational pattern is represented by the stage wise implementation of business process change as depicted by the stage-activity (S-A) framework of BPR implementation (Kettingeret al., 1997). The S-A framework has been based on extensive review of literature on BPR methodologies, tools and techniques and interview with practitioners (Al-Mashari and Zairi, 2000) and thus is a comprehensive representation of business process redesign spread over six stages. The inferential task involves the attempt to relate, link or match the theoretical and observational patterns to develop the framework.

Based on the S-A framework of Kettingeret al.(1997), the BPM implementation has been conceptualized to occur over three phases – conceptual, design and execution. The conceptual phase is where the process value chain is aligned to the strategic objectives and matches with the Envision and Initiate stage activities of the S-A framework. The design phase involves the redesign of the process creating new workflows and linkages required to implement the new value chain conceptualization and matches with the Diagnose and Redesign stage activities of the S-A framework. And the execution phase involves the rollout of the new practices and processes as part of the new workflow and matches with the Reconstruct and Evaluate S-As of the S-A framework.

To address organizational change alignment during the three key phases of BPM implementation one of the most comprehensive internal and external strategic alignment model, Higgins’s (2005) 8-S Model of Strategy Execution, a revision of McKinsey’s 7-S Model (Peters and Waterman, 1982) is used. The 8-S model states that Strategic performance as desired can be achieved by organizations only if eight key organizational factors including Structure, Systems and processes, leadership Style, Staff, reSources, and Shared values are aligned with Strategy. Table II shows how the activities across the BPM implementation phases map with the primary factors in the 8-S model.

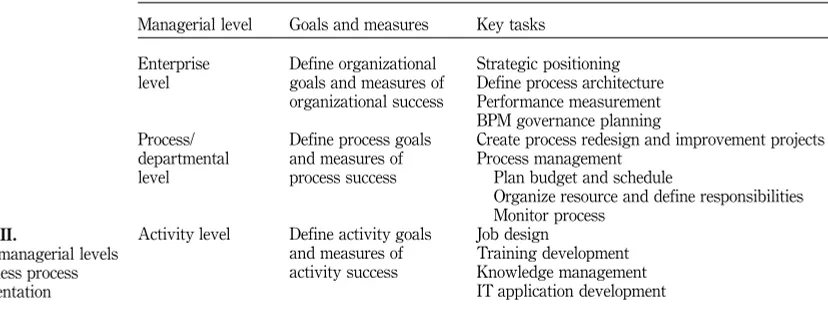

4.3 Role of managerial levels in business process implementation

The involvement of different managerial levels in different stages of BPM implementation is supported by Ko’s (2009) typology of business processes into

981

Business process

redesign

operational, management and strategic levels based on management activities. Even Andreuet al.(1997) work on process innovation indicate integration of learning across individual, organization and business levels. According to Harmon (2007) business process change initiatives involve three levels of managerial concern – enterprise level, process/departmental level and activity level. Differentiation between the levels is necessary as activities at different levels require different participants, different methodologies and different types of support (Harmon, 2007). The goals and tasks associated with the three levels are depicted in Table III.

4.3.1 Enterprise level managers. The primary role of the enterprise level managers is to obtain the alignment of the 8-S dimensions – Strategy, Shared values and reSources. During the conceptual phase, the enterprise level managers play a primary role in identifying the value chain that would serve the strategic objectives. This would require these managers to understand the organization goals and relate what business processes would be required to meet the goals.

However, for the BPM implementation to be successful this envisaged value chain needs to be have the buy-in of the process/departmental managers as the execution of

Kettingeret al.(1997) S-A framework Higgin’s 8 S alignment factors BPM phases Stages Activities

Conceptual (linking value chain to strategy)

Envision Establish management commitment and vision Discover reengineering opportunities

Select processes for redesign

Strategy

Initiate Inform stakeholders Shared values Organize reengineering teams reSources Conduct project planning

Design (design of workflow)

Diagnose Document and analyse existing process Structure Redesign Prototype and detailed design of new process Structure

Design human resource structure

Analyse and design Systems Execution

(executing the practices)

Reconstruct Reorganize human resource roles Train users

Style Staff Evaluate Evaluate performance Strategic

Link to continuous improvement Performance

Table II.

Mapping of alignment factors across BPM Phases

Managerial level Goals and measures Key tasks

Enterprise level

Define organizational goals and measures of organizational success

Strategic positioning Define process architecture Performance measurement BPM governance planning Process/

departmental level

Define process goals and measures of process success

Create process redesign and improvement projects Process management

Plan budget and schedule

Organize resource and define responsibilities Monitor process

Activity level Define activity goals and measures of activity success

Job design

Training development Knowledge management IT application development

Table III.

Role of managerial levels in business process implementation

982

BPMJ

20,6

the new value chain would impact on the functioning of the departments. One of the major difficulties of getting the buy-in is that process/departmental managers have developed a mental frame of how work is being done and what roles they play. Obtaining the buy-in would require the enterprise level managers to change the perspective of the process/departmental managers towards the new value chain. This would require the alignment of the mental frame of the process/departmental managers with the enunciated strategic values of the organization. Execution of the new business process would require resource acquisition to support the business process accordingly. As enterprise level managers controls the mobilization and allocation of resources, it could align the existing organizational resources with the requirements of the new value chain and thus drive change in the behaviour of process/ departmental managers. According to Noda and Bower (1996), the escalation of a firm’s strategic commitment to the new businesses is a consequence of iterations of resource allocation. So the enterprise level managers need to play a primary role in obtaining the resource alignment with the redesigned business process.

The new business process would require the buy-in of the activity level managers for successful implementation. This would require a behavioural change of the activity level managers. As the activity level managers are not under the direct control of the enterprise level managers, they would only be able to impact the behavioural change through indirect methods like sharing the strategic vision. Thus enterprise level managers would play a primary role in creating a shared understating within the wider organization of the role of the new business process in meeting the strategic goals.

4.3.2 Process/departmental level managers. As part of managing the technical process of the BPM, the process/departmental level manager’s role is to detail the conceptualized value chain by designing the workflows and interactions, both inter and intra department. To facilitate the business process redesign, the process/ departmental level managers play a primary role in seeking to obtain alignment of the Structure and Systems dimensions of the 8-S framework. The envisaged value chain would require redesigning the business process thus impacting the structural relationships, both intra and inter – process/departmental. The achievement of the goals of the envisaged value chain would require reorienting the existing relationship between processes/departments. As discussed earlier, enterprise level managers would allocate resources to process/departmental managers based on their ability to support the organizational goals. Thus process/departmental managers would work towards realignment of the existing intra and inter-process/departmental structural relationships to forge new structural relationships.

Design of workflows to support the new business process would require new tasks, roles, knowledge, etc. However, at the activity level there exist a mental model of doing work based on the existing systems and processes. Execution of the new business process would require that these systems and processes are modified or adapted to the requirements of the systems and processes of the new business process. Thus, this would require the process/departmental managers to align the existing systems and process with the new design of the workflows and interactions.

4.3.3 Activity level managers. As part of the BPR’s technical process the role of the activity level managers is to detail and operationalize the rules, roles, methods involved within each individual task of the workflow. In the process of integrating managing change with business process implementation, the activity level managers play a primary role in seeking alignment of the Staff, Style and Strategic performance dimension of the 8-S framework.

983

Business process

redesign

Executing the new business process would require unlearning and relearning new operational doctrines. As operational doctrines requires the involvement of the people singularly or in groups or in conjunction with technology, the unlearning and relearning would involve the organizational staff. However, all staff may not be equally motivated or able to unlearn and relearn the operational doctrines. To facilitate effective execution, it would be necessary for the activity level managers to identify and train staff who can bridge the gap between the old and new operational doctrines. This would ensure an effective alignment between the old and new operational doctrines with individual capabilities and attitudes.

In order to support the strategic objective, operational execution of the business process would also require integration of the behavioural culture with the desired strategic values. For example, if the business process change calls for increased customer responsiveness, the executional success would also need change in behaviour of operatives towards customer service. This would require the activity level managers to initiate change in their working style. As stated earlier, the dissemination of the strategic values are primarily controlled by the enterprise level managers and therefore there is a need to align the behavioural style of the activity level with the shared values propagated by the enterprise level. In this process, the activity level managers would play a significant role in aligning their behavioural style with the shared values propagated by the enterprise management.

The achievement of the organizational goals through business process implementation is based on how effectively the execution of the business process meets the customer objectives. Thus it is necessary that the activity level managers would need to develop measures for the business process activities that are aligned with the strategic objectives. For example, achievement of strategic objective of better customer satisfaction would require customer interface operations to be measured by waiting time of the customer. Therefore, one of the roles of the activity level managers is to develop operational measures that achieve alignment of operational outcomes with the strategic goal as envisaged in the redesigned business process.

Figure 2 represents the model for aligning business process redesign with managing change using Higgin’s (2005) 8-S model during BPM implementation. The model depicts the role of the different managerial levels in facilitating the alignment of the different 8-S dimensions with the BPM technical process. The model also depicts the sequence of alignment of the 8-S dimensions over the different phases of the BPM implementation. The role of the different managerial levels in the alignment is discussed.

5. Case studies of business process implementation 5.1 Case study 1: automated and integrated customer care system

This case is about the business process change at one of the oil and gas company in UAE which has its core value chain processes and sub-processes organized in a sequential fashion. Specifically the primary activities of the vertically integrated value chain include inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics and marketing and sales, comprising specific sub-processes. The business process change was to restructure the customer care process as the company felt that the customer care system was falling short of meeting the customer expectations. The existing customer care process was considered the responsibility of the marketing and sales department and was not integrated with the other functions. While the legacy system of resolving customer complaints was based on trust and prior experience, difficulties were increasingly being experienced when handling non-routine requests, an outcome of the highly fragmented

984

BPMJ

20,6

Phases of BPM Design

Conceptual Execution

Managerial Levels

Enterprise Level

1

Process/ Departmental

Level

Activity Level

. Strategic goals

Identifying the strategic value

chain 1

Managerial mental frame

of work organization

3

Design of workflows &

interactions 4

Detailing operational

doctrines Logic for behavioral

change 2

Ingrained work practices

& attitudes 5

7

6

8

Dimensions of alignment: 1, Strategy; 2, Shared values; 3, Resources; 4, Structure; 5, Systems & processes; 6, Style; 7, Staff;

8, Strategic performance Technical sub-process element Change sub-process element

Figure

2.

Op

erational

framework

of

BPM

alignment

985

Business

pr

ocess

redesign

and functional structure of the organization which was inappropriate for an increasingly dynamic environment. Furthermore, inability to resolve customer related issues in a timely fashion perpetuated a culture of denial and blame, thus resulting in misalignment with the key strategic objectives of customer satisfaction.

The first stage of the business process change in this particular organization was to rearticulate the customer care process as an important element in achieving the customer satisfaction leading to the decision to redesign the existing customer care process into an integrated process. This led to the second stage that was defined by mapping the scope of an electronically driven integrated process which would form the basis for IT integration, drawing workflows with specific responsibilities and finalizing measurement metrics. This task was facilitated by the appointment of a cross-functional team by the top management and included members from different departments and hierarchy levels of the company. The participants in the cross-functional team were considered as key change sponsors who were expected to train and communicate the new process within their respective domain.

The third stage was the rollout of the redesigned process which involved creating new roles, work practices and accountabilities, and performance measurement metrics to replace the existing work practices of the erstwhile process. This was to be followed by the training of employees to be involved in the redesigned process.

However, despite the careful planning, the envisaged business process change was unable to meet the expected objectives, with the execution process itself getting delayed. Evidence indicated that although in the initial two months after implementation of the new system, most departments were logging into the new system, thus showing some adaptability, there was a dramatic decline in usage of the new system by the third month, with many employees showing resistance and tendencies to revert back to the “old informal way of handling customer complaints”.

5.1.1 Diagnosis of failure. A diagnosis of the envisaged business process change indicated some implementation gaps within the organization. For example, although the new customer care process and the need for the same was widely communicated and endorsed strongly by senior management at the beginning of the launch itself, thus creating an awareness of the change itself, lack of continuous sponsorship and engagement by the management at all levels was a major factor that impacted the momentum for change. Furthermore, while the end-users were aware of the “what” of the business process change, they had limited information regarding the “why” and “how” of change thus reducing their desire to adapt to the new process. Although knowledge in the usage of the new process was provided through interactive mail, this was inadequate and misaligned with existing low skill-levels among the employees who would have benefitted more from face-to-face training at a pace that matched their capability levels.

A second factor that impeded the change was the traditional culture driven by a compartmentalized approach to the customer care process with employee perceptions that accountabilities of the customer care process rested with the marketing and sales department. Such a mind-set was in direct contradiction with the cross-functional mind-set and skill-set the employees were now expected to have within the changed customer care scenario. Furthermore no process interventions were provided to address cross-functional conflict that inevitably resulted out of the new way of functioning. Lack of shared values that focused on teamwork was further compounded by a functional hierarchical structure which continued to have performance management practices that focused on individualized goal-setting mechanisms.

986

BPMJ

20,6

Mapping of case study 1 on the alignment framework is shown in Figure 3. The mapping shows that the enterprise level management carried out the tasks of “articulating a new vision” and “appointing cross sectional team” to achieve alignment of the Strategy and reSource dimensions. The process/departmental managers achieved the alignment of the Structure dimension by carrying out the task of “IT integration”. These facilitated the smooth transition of the BPM from the conceptual to the design phase leading to the development of the electronic process. However, the process/departmental managers were not able to achieve alignment of the Systems dimension as they failed to “impart proper training” to the activity level managers which led to “non-development of skills” leading to weak alignment of the Staff dimension. Similarly, the enterprise level management were not able to effectively “communicate the need for new process” to the activity level managers causing weak alignment of the Shared values dimension which led to no “behavioural change” in the activity level managers thereby achieving weak alignment of the Style dimension. Thus the envisaged business process redesign to the new automated and integrated customer care process failed to move effectively from the design to the execution phase and achieve the intended strategic outcomes due to the weak alignment of the Style, Staff, Systems and Shared values dimensions.

5.2 Case study 2: automated distribution centre (ADC)

This case reports changes in the value chain processes implemented in a UAE-based company with a diversified portfolio of products and services in the IT and telecom sector, and which has recently progressed from being a distributor for IT products to a fully integrated supply chain solution and service provider. The process change that was implemented resulted out of a need to support increasing business volume through world class warehouse and inventory management system. The strategic vision of the company was to transform from a “responsive warehousing system” to a “response-efficient distribution centre” with the expected outcome of improved service quality and increased profitability.

The specific change envisaged required the redesign of the warehousing management processes linked to the value chain of volume distribution to achieve process optimization and thus speed up the organization’s goal to be the number one IT and Telecom distributor in the MENA region. Thus strategic alignment was the key driver for the process change and service maximization was the key benefit expected. The task involved was to automate the distribution centre to address existing problems such as:

. inefficient utilization of manpower due to manual stock-counting;

. inefficient data exchange processes related to shipment and item tracking; . inefficient space utilization, resulting in overcrowding of ground space; . lack of timely and complete information on resource-utilization leading to

questions regarding productivity; and

. non-availability of timely and adequate pallet information resulting in

difficulties with regard to item-wise tracking of shipment after goods are issued.

All the above issues resulted in poor quality of service, inadequate infrastructure to accommodate rising business volumes and resulting in lack of mobility and capability issues.

987

Business process

redesign

Phases of BPM Design

Conceptual Execution

Managerial Levels

Enterprise Level

Process/ Departmental

Level

Activity Level

. Remove

bottleneck in customer service

Develop integrated customer care process architecture

1: articulate new vision

Customer care is not only responsibility of marketing alone but all functions

3: appoint cross sectional team

Design electronic driven integrated customer care

process 4: IT integration

New roles, work practices & performance metrics

Culture of integrated teamwork in customer care 2: no communication of

“how” & “why” of change

Mindset that customer care is

responsibility of marketing only 5: no proper training, no cross

functional shared values

7: skill not developed

6: old way of doing thing

8: no decrease in customer complaints

Dimensions of alignment: 1, Strategy; 2, Shared values; 3, Resources; 4, Structure; 5, Systems & processes; 6, Style; 7, Staff; 8, Strategic performance

Technical sub-process element Change sub-process element weak alignment

Figure

3.

Op

erational

framework

of

BPM

alignment

in

case

1

988

20,6

BPMJ

In order to address the above issues and to support the next stage of the business expansion program, the ADC was set up to manage the flow of goods, improve delivery capability and overall service quality. Besides being strategically located (close to the sea port and the international airport), the specific features of ADC included substantial increase in space with docking stations, narrow aisle technology, material handling equipment, advanced radio frequency technology and WIFI enabled warehouse.

However, while customized information systems facilitated by SAP helped tracking and notification of shipment on timely bases, the change failed to achieve economies of scale and service, resulting in blaming, low morale and decreased responsiveness. Specifically the following negative outcomes were noticed:

. increase in turnaround time;

. obstruction of pallet movement due to uncertainty in customer pick-up time; . increase in shipment packing time; and

. reduced speed of service due to partial (loose picking).

5.2.1 Diagnosis of failure. The diagnosis revealed that while technical dimensions of the process change had been addressed through careful project management, the change management dimensions were not adequately addressed. Specifically, the end users were unaware of the rationale for the change or the associated benefits. Lack of involvement during the design and execution of the new automation process resulted in decreased appreciation or desire for adapting to the new system. The problem in capabilities was further compounded by the provision of training opportunities, just a month before the actual execution, which was inadequate for understanding the operational dimension of the new process, leading to increased resistance towards adoption of the new system. Besides, not enough time was available for people to get familiar with the system leading to increased learning anxiety. Furthermore, since there were no reinforcement mechanisms or modification to reward systems, sustaining the change became difficult. Undue pressure from management to deliver and fulfil, the increasing customer demands was also perceived as a constant interference in operation. In essence the improvements in quality and service that were expected out of the ADC were not realized leading to a gap between strategic intent and strategic outcome.

Mapping of case study 2 on the alignment framework is shown in Figure 4. The mapping shows that the enterprise level management carried out the tasks of “articulating a new vision” and “investment in SAP technology” to achieve alignment of the Strategy and reSource dimensions. The process/departmental managers achieved the alignment of the Structure dimension by carrying out the task of “setting up ADC”. These facilitated the smooth transition of the BPM from the conceptual to the design phase leading to the development of the ADC with SAP. However, the process/ departmental managers were not able to achieve alignment of the Systems dimension as they failed to “involve in the design” the activity level managers which led to “learning anxiety” leading to weak alignment of the Staff dimension. Similarly, the enterprise level management were not able to effectively “communicate the benefits of new process” to the activity level managers causing weak alignment of the Shared values dimension which led to “negative behaviour” in the activity level managers thereby achieving weak alignment of the Style dimension. Thus the envisaged business process redesign to the ADC process failed to move effectively from the design to the execution phase and achieve the intended strategic outcomes due to the weak alignment of the Style, Staff, Systems and Shared values dimensions.

989

Business process

redesign

Phases of BPM Design

Conceptual Execution

Managerial Levels

Enterprise Level

Process/ Departmental

Level

Activity Level

. Support increased

business volumes

Transform to a “response-efficient distribution centre”

1: become no. 1 in MENA region

Remove inefficiencies in

distribution operation

3: investment in SAP technology

Automation of distribution centre operations with SAP 4: Setup

Automated DC

New roles, work practices & performance metrics

Culture of integrated teamwork in customer care 2: no communication of

“nature” & “benefits”of change

Appreciation of new system not developed 5: no involvement of operatives

in design,last minute training

7: learning anxiety

6: change perceived as interference, blame game

8: expected outcomes not achieved

Dimensions of alignment: 1, Strategy; 2, Shared values; 3, Resources; 4, Structure; 5, Systems & processes; 6, Style; 7, Staff; 8, Strategic performance

Technical sub-process element Change sub-process element weak alignment

Figure

4.

Op

erational

framework

of

BPM

alignment

in

case

2

990

20,6

BPMJ

6. Validation of alignment framework

Drawing from the key results as illustrated in the two cases of business process change, it may be deduced that while the strategic intent was derived out of required business deliverables in the context of a changed economic landscape, the strategic outcomes were not attained due to flawed business process implementation. The main factor that emerged as common themes in both cases was the lack of alignment between the culture, process, task and roles with the new strategy and structure of the proposed business process. Thus while the technical dimension of the business process was well thought-out and implemented, the lack of alignment of the key dimension at the activity level was a key factor in preventing the success of the change. The case studies reveal the emergence of the following patterns which validates the conceptualization of the alignment framework.

Comparison of the mapping of the business process change implementation phases for both the case studies, as shown in Figures 3 and 4, respectively, show that the process of business process change involves three phases – conceptual, design and execution. The conceptual phase is where the process value chain is aligned to the strategic objectives. The design phase involves the redesign of the process creating new workflows and linkages required to implement the new value chain conceptualization. And the execution phase involves the rollout of the new practices and processes as part of the new workflow. This phase wise implementation of business process change is in consonance with the conceptualisation of the alignment framework of business process implementation. The mapping also indicates that the framework can be applied in the real world context.

The comparison of the case studies indicate that the three phases of business process implementation is carried out by different levels of the organization. As evident in Figures 3 and 4, the conceptual phase involves activities like “rearticulation of vision” or “create response efficient distribution” which are strategic in nature and were carried out by the enterprise level managers. During the design phase, the activities involved “design of electronic process” or “automation of distribution centre operations” and was performed the process/departmental level managers in the organizations. While during the execution phase, activity level managers were entrusted to implement the redesigned process. Thus it could be observed that the three phases of BPM implementation had the primary responsibility of different organizational levels – enterprise level managers, process/departmental level managers and activity level managers. This is in consonance with the conceptual alignment framework where the primary responsibilities of the three implementation phases have been assigned to different organizational levels.

In both the case studies, the enterprise level management assigned the resources for developing the new process like “invested in SAP technology” and “facilitated cross departmental team”. Both these evidence support the fact that the enterprise level management was instrumental to achieve the alignment of the reSources dimension of the 8-S framework. This observation is in agreement with the envisaged role of enterprise level managers in the alignment framework where it uses resource allocation to induce structural change. As hypothesised in the alignment framework, achieving the alignment of reSources dimension during the business process conceptual stage by the enterprise level managers would facilitate advancement of the design of the new business process. This is evident from the case studies where the business process implementation moved smoothly to the design phase due to the enterprise level manager’s role in achieving the alignment of the desired reSources

991

Business process

redesign

dimension. Also the case studies indicate that the redesigned business process did not have successful operationalization due to the lack of alignment of the Systems and Staff dimensions with the new business process. As per the alignment framework, the process/departmental management’s primary role is to achieve the alignment of the Systems factor and in both cases the process/departmental managers were not able to create the necessary system to support the new process.

The enterprise level management’s primary role is to share strategic values down the organizational hierarchy. However, in both the cases, the enterprise level management did not have any interaction with the activity level managers and thus failed to share the new strategic direction. So it could be observed in both the cases studies that behavioural change of the activity level managers did not take place. This substantiates the role of activity level management in the alignment framework who would align their behavioural style with the Shared values of the enterprise level management. Thus the two case studies provide evidence of business process implementation issues that validate the conceptualisation of the alignment framework in Figure 2.

7. Conclusion

Though BPM was supposed to provide a holistic management philosophy that focus on aligning all aspects of the organization, for practical purposes BPM implementation is primarily focused on the technical aspect of business process or workflow management. This view is supported by Koet al.(2009) who found that many BPM Suites are actually workflow management systems. With the growing adoption of BPM Suites by organizations this would lend credence to the belief that in practice the consequent organizational change process associated with workflow redesign is not getting addressed adequately within organizations. By delineating the interaction of the 8-S dimensions with the technical dimension of BPM implementation, the model provides the manager an operational tool on how to achieve this alignment in the most effective manner. Second, most of BPM practitioners have been accustomed to a surfeit of tools and techniques available for workflow management but none in the area of change management. The operating model proposed in this paper could act as a tool for implementing change management during BPM.

The need for alignment of the technical process with the organizational change process in BPM has not received adequate attention. In this context, this study provides a framework for alignment of the technical dimension of business process redesign with the human dimension of organizational change, a perspective that has been missing in the literature on BPM implementation. Second, it is believed BPM lacks clarity (Harmon and Wolf, 2008; Doebeli et al., 2