Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 18 January 2016, At: 20:01

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

ON-LENDING IN INDONESIA: PAST PERFORMANCE

AND FUTURE PROSPECTS

Blane D. Lewis

To cite this article: Blane D. Lewis (2007) ON-LENDING IN INDONESIA: PAST PERFORMANCE AND FUTURE PROSPECTS, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 43:1, 35-58, DOI: 10.1080/00074910701286388

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910701286388

Published online: 08 Nov 2007.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 79

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/07/010035-23 © 2007 Indonesia Project ANU DOI: 10.1080/00074910701286388

ON-LENDING IN INDONESIA:

PAST PERFORMANCE AND FUTURE PROSPECTS

Blane D. Lewis*

World Bank, Jakarta

On-lending to sub-national governments in Indonesia has a long and generally dis-appointing history. Among other noteworthy problems, an insuffi cient amount of

funds has been channelled through the system vis-à-vis capital fi nancing needs, and

loan repayments have proved poor. Aid agencies and government have recently invested substantial resources in attempts to improve the on-lending system; the re-sultant newly installed regulatory framework for sub-national borrowing is, how-ever, unlikely to improve outcomes substantially. Developing sub-national govern-ment access to private capital markets would appear to constitute the way forward, although this will not come quickly or easily. A positive step in the right direction would be for government and aid agencies to embrace the anticipated change and work together to make the transition a successful one, rather than continue to tinker with reforms at the margin of a moribund system.

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

On-lending refers to the means by which international aid agencies and central gov-ernments channel long-term fi nance to sub-national governments.1 In this context, aid agencies make loans to the central government and to (mostly) publicly owned and managed fi nancial institutions which, in turn, on-lend the funds to sub-national governments. And central governments lend to their sub-nationals from their own resources, either directly or via public fi nancial institutions.2 On-lending is a com-monly used tool to fi nance local public infrastructure in developing countries, espe-cially in cases where capital markets are relatively under-developed.

* The author is Senior Adviser for Fiscal Decentralization at the World Bank in Jakarta un-der fi nancing from the Dutch Trust Fund (TF050378). The views expressed here are those of

the author and should not be attributed to the World Bank or the government of the Neth-erlands. The author would like to thank Indonesia’s Ministry of Finance for access to data used in this paper; Kutlu Kazanci for expert research assistance; and Sebastian Eckardt, Andre Oosterman, Bill Wallace, David Woodward, two anonymous referees and the editor for comments on earlier versions of the paper.

1 On-lending may also be used in some countries to channel fi nance to national

state-owned enterprises. This paper considers only on-lending to sub-national governments (and sub-national government enterprises).

2 Very occasionally, publicly sponsored fi nancial intermediaries also access funds from

private capital markets, which are then on-lent to sub-nationals.

In Indonesia, international aid agencies lend to sub-national governments and their enterprises through the central government’s mechanism for on-lending foreign funds, the Subsidiary Loan Agreement (SLA). The most important aid agencies involved in on-lending to sub-national units are the World Bank (WB) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB), although other development assistance agencies have also been involved.3 The central government makes loans to sub-nationals through its Regional Development Account (RDA).4 RDA loans are, for the most part, sourced from own domestic public revenues, although a minimal amount of funding has come from aid agency (ADB and United States Housing and Environmental Credit Guarantee program) contributions.

Research focused specifi cally on on-lending is somewhat limited. In the only widely available comparative study on the topic, Peterson (1996) evaluates the performance of on-lending in 25 countries. The basic conclusion reached was that on-lending has not worked satisfactorily. In this regard, three outcomes in par-ticular appear to be the norm. First, insuffi cient funds are transferred through on-lending mechanisms to meet sub-national infrastructure fi nance needs. Second, various intermediation functions are performed poorly by the central govern-ment and other relevant fi nancial institutions.5 Third, loan repayments are weak (Peterson 1996).

In a study specifi c to Indonesia, Devas and Binder (1989) broadly examine early SLA on-lending and that of RDA’s forerunners—Rekening Dana Investasi (RDI) and the Inpres Pasar program,6 among others. The authors criticise the near exclusive focus of such lending on revenue-generating projects, which they argue is ineffi cient and inequitable.7 In Lewis (2003) I analyse the Indonesian experience of on-lending to local governments through 1999, concentrating on the evident poor loan repayment record. I fi nd that frequent non-repayment of loans appears to result not from

inabil-3 Other aid agencies include, most importantly, those of France, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United States.

4 Throughout this paper, ‘RDA’ refers to lending carried out by the RDA, as well as that by its predecessor programs, including the Investment Fund Account (Rekening Dana Investa-si, RDI), Inpres Pasar, and others (Inpres stands for ‘Instruksi Presiden’, the name given to a program of special grants from the central government; footnote 6 explains ‘Inpres Pasar’). The RDI and Inpres Pasar programs’ loans have since been rolled into RDA operations. 5 In many cases these functions extend beyond the simple supply of credit and collection of repayments, to include performing fi nancial and economic project appraisals,

blend-ing grants with loans, overseeblend-ing project preparation and implementation, and providblend-ing technical assistance in fi nancial management (Peterson 1996).

6 RDI loans were used to fi nance various types of sub-national government infrastructure;

Inpres Pasar loans were exclusively for market construction.

7 It is usually argued that it is more economically effi cient to borrow now in order to

sat-isfy present needs or demand than it would be to wait until adequate funds can be accumu-lated over time. Borrowing for capital development is deemed equitable, since those who actually use the generated services can be made to pay for them over the course of the life of the infrastructure. (Note that the latter also supports the economic effi ciency argument.)

Signifi cant effi ciency and equity improvements are forgone by restricting borrowing to

revenue-generating projects.

ity to repay but rather from a lack of willingness to do so.8 In addition, I argue that neither the central government nor aid agencies have shown much interest in forcing better repayment. The latter, at least, lack an incentive to do so, since their loans are repaid by the centre regardless of whether local governments repay or not.9

A related strand of research examines the constraints that sub-national govern-ments face in moving beyond the use of narrow on-lending mechanisms to access private capital markets. Freire and Petersen (2004) discuss the basic requirements of sub-national capital market development, focusing on the political, legal, and fi nancial regulatory environment and appropriate market-based borrowing instru-ments. They investigate the situation in 18 countries across Latin America, Africa, Asia and Eastern and Central Europe. One of the countries reviewed is Indonesia. The authors of the Indonesia chapter note that the lack of security provisions in law, and uncertain legal requirements concerning sub-national fi nancial reporting and disclosure, such as existed during the period just after the launching of the govern-ment’s decentralisation program in 2001, were important constraints to the devel-opment of market-based approaches in Indonesia (Kehew and Petersen 2004).

Martell and Guess (2006) develop a framework for assessing the readiness of sub-national governments to employ market-based debt fi nancing, and apply the framework to fi ve countries, including Indonesia.10 Their general thesis is that the successful development of sub-national capital markets is a function of the regu-latory framework and fi nancial institutions’ ability to evaluate credit risk, most importantly, and sub-national governments’ capacity to properly manage debt, to a secondary extent. The authors fi nd that, among the countries examined, sub-national governments in Indonesia show the least potential for accessing private capital markets, judging from the institutional environment that existed during the early years of decentralisation.

The broad objectives of this paper are to provide a historical review of lending and to assess the near-term prospects for on-lending and alternative methods of fi nancing sub-national public capital development in Indonesia. To the author’s knowledge there is no published research focused on the history of, and prognosis for, on-lending in any country. And while there has been some work on the possibilities surrounding the development of sub-national government access

8 Note that this statement pertains to local governments only and not necessarily to local government water enterprises, which were not examined in the cited study. Many water enterprises may be unable to service their loans; of course this inability to repay is in many cases a function of tariffs being set at below cost-recovery levels. Improper setting of tariffs for services is a signifi cant problem in Indonesia. Further analysis of this problem is,

how-ever, beyond the scope of the present paper.

9 There has been a considerable amount of unpublished research and writing on lending in Indonesia. These efforts describe the status of SLA and RDA portfolios at par-ticular points in time (Lewis 1997a, 1997b; Woodward 2000, 2005); examine the regulatory framework and procedural arrangements for on-lending (Woodward 2000; Oosterman and Samiadji 2004; Oosterman 2005; and Lewis and White 2005); and explore the possibilities for moving beyond on-lending to sub-national units (Research Triangle Institute 1999; Var-ley 2001; Weitz 2001; and Development Alternatives 2002).

10 Other countries included in the analysis are Mexico, the Philippines, Poland and South Africa.

to capital markets in Indonesia (among other countries—see above), these analy-ses were based on a regulatory system that has now been replaced. As such, this paper should help to fi ll a signifi cant gap in the literature and also provide some updated information on a research topic previously considered.

The focus of the historical investigation is on evaluating the magnitude and performance of SLA and RDA on-lending from 1975 to 2004. In this regard, the paper pays special attention to the infl uence of the major lenders in explaining loan performance during this period; differential outcomes associated with central government, WB and ADB lending are highlighted throughout the study. Gov-ernment and major international aid agencies have, in recent years, focused their resources on improving on-lending; relatively less attention has been paid to devel-oping more market-based systems. The future prospects of on-lending in Indonesia depend on the extent to which performance across a number of dimensions can be enhanced. The paper examines the possibilities in this regard in light of the new and still emerging regulatory framework for sub-national borrowing in general and on-lending in particular. Successful development of alternative market-based methods of sub-national fi nance also depends in part on the new regulatory framework, and the study briefl y explores the potential in this regard as well.

The paper proceeds as follows. First, some background material on SLA and RDA on-lending is presented, the data used in the analysis are briefl y described, and basic empirical facts about on-lending are provided. Second, information on the number of loans, the amount of loan fi nance, and loan repayment perform-ance, organised according to borrower characteristics and by lender, is supplied; in addition, this section of the paper examines government and aid agency allocation of loan fi nance across borrower types and locations. Third, a prognosis for contin-ued on-lending is offered and alternative options are briefl y considered. Finally, the paper summarises the main points of the investigation and offers some pol-icy conclusions relevant to lending to sub-national governments in Indonesia. An appendix provides a formal empirical examination of the relationship between loan repayment and certain loan and borrower characteristics and major lenders.

SLA AND RDA ON-LENDING

AND SOME PRELIMINARY EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE SLA and RDA on-lending11

SLA and RDA on-lending mechanisms have been used to channel long-term fi nance for infrastructure development to provinces, local governments12 and local water enterprises (perusahaan daerah air minum, PDAMs).13 Interest rates on both SLA and RDA loans have varied quite signifi cantly over the years, ranging from zero to around 13%. Since the early 1990s, however (until very recently), SLA and RDA loan rates have been fi xed at 11.5% (although SLA loans typically carry an extra

11 This section draws heavily on Research Triangle Institute (1999) and Lewis (2003). 12 Local governments comprise municipalities (kota) and districts (kabupaten).

13 Most on-lending to provinces and local governments has gone towards fi nancing the

construction of transport terminals and markets and, to a somewhat lesser extent, roads and drainage systems.

0.25% interest charge remitted to commercial banks responsible for collections—see below). Loan grace periods and maturities have usually been set at 3–5 years and 18–20 years, respectively, for both SLAs and RDAs. SLA loan interest is capitalised during grace periods, while RDA loan interest accumulates during grace periods;14 both SLA and RDA loan funds are disbursed at regular intervals during grace peri-ods against evidence of project expenditures. Repayment schedules typically com-prise equal instalments on principal, and interest is paid on the declining balance;15 repayments are due every six months after the grace period expires. The Ministry of Finance (MOF) oversees both SLA and RDA on-lending mechanisms.

Three issues regarding the implementation of SLA and RDA on-lending merit attention. The fi rst relates to the relative demand orientation of SLA and RDA lending. In years past, SLA lending, particularly as associated with the multi-lat-eral aid agencies’ Integrated Urban Infrastructure Development Program (IUIDP), was frequently criticised for being ‘supply-driven’. Many sub-national govern-ment offi cials argued that IUIDP projects were, in large measure, designed by aid agency-fi nanced consultants, without much local government or community involvement. In addition, it has been asserted that loans were often just ‘assigned’ to the local government by the centre as the means by which the projects would (at least partially) be fi nanced. In some cases, local offi cials claimed not even to have understood that they were signing loan agreements.

The RDA was created in 1988 in part to be more responsive to sub-national gov-ernment demand for infrastructure fi nance than SLA lending was perceived to be. As such, RDA lending was from the start based on individual project proposals from sub-national governments and enterprises, rather than on integrated infra-structure projects designed and promoted by aid agencies. Whether RDA lending has actually achieved more of a demand orientation than SLA lending is a matter of some dispute, however. At least some research has argued that many projects designed by the Department of Public Works and fi nanced by RDA loans seem also to have followed a supply-led approach (Research Triangle Institute 1999).

Second, obtaining SLA and RDA project and loan approvals has proven burden-some for borrowers. SLA projects can take three to fi ve years to be developed and begin implementation. IUIDP project development, approval and start-up was especially time consuming. Those projects were multi-sectoral and therefore rela-tively complicated by nature; attendant loans were usually part of a larger fi nancing package, which needed to be approved in its entirety before project implementation could begin. RDA project approval and start-up has typically been less onerous than that for SLAs, but may still take up to two years. The shorter time line for RDA lending is mainly a function of the simpler nature of the projects themselves; that is, loans have exclusively fi nanced single, stand-alone projects.

The third issue of note concerning SLA and RDA on-lending relates to loan administration. The disbursement of SLA loans is initiated by the Directo-rate of Budget Administration in MOF’s DirectoDirecto-rate General of Budget; RDA

14 Capitalised interest refers to the compounding of annual interest charges against prin-cipal and accrued interest during the grace period. Accumulating interest means that an-nual interest charges are applied only to the original principal during grace.

15 Occasionally repayment schedules of RDA loans have been based on fi xed principal

and interest instalments.

disbursement orders are given by the Directorate of On-lending, which is (now) located in the Directorate General of Treasury, MOF. Each directorate has tended to keep relevant disbursement information to itself. This has sometimes caused diffi culties for the Directorate of On-lending, which is charged with compiling repayment schedules for both SLA and RDA loans, for which precise informa-tion on the amount and timing of disbursements is required. More important for the present examination are the differences related to loan repayment collection. Collection of SLA loan repayments is the responsibility of local ‘handling’ banks, typically local branches of state banks, which are nominated in the individual loan agreements between aid agencies and the government. As noted above, the handling bank charges an annual fee, amounting to 0.25% of the outstanding loan amount. Collection of RDA loan repayments, on the other hand, is administered entirely by the Directorate of On-lending, Directorate General of Treasury, MOF, and no additional charges are levied (Woodward 2000).

Data and preliminary empirical evidence

The data used in this paper are from the Directorate of On-lending, MOF. The data set comprises all SLA and RDA loans to sub-national governments and PDAMs from 1975 through 2004. A total of 838 loans were extended over the period to 426 borrowers. For each loan, information is available on the name of the borrower; the source of funds (i.e. the lender); and the year, amount, interest rate and matu-rity of the loan. In addition, repayments due, made and in arrears are recorded for each loan, as well as the outstanding principal.

In aggregate, lending to sub-national units through the SLA and RDA mecha-nisms has not been very signifi cant. By the end of 2004, the total outstanding debt of sub-national governments and water enterprises was Rp 4.2 trillion; by comparison, the outstanding debt of the central government at the end of 2004 was Rp 1,291.3

1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000

0.0 1.5 3.0 4.5

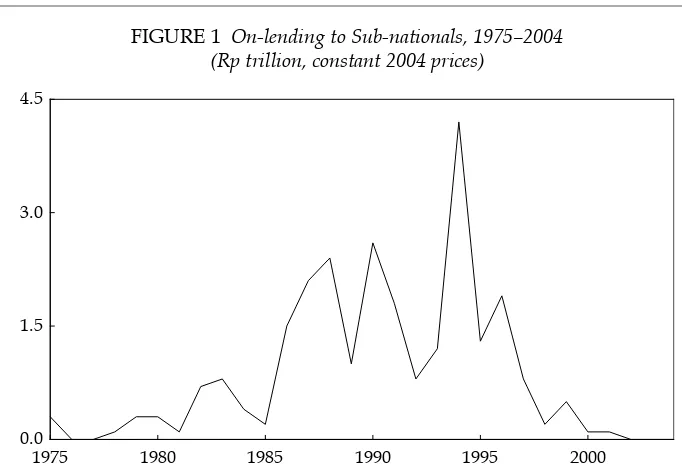

FIGURE 1 On-lending to Sub-nationals, 1975–2004 (Rp trillion, constant 2004 prices)

Source: Ministry of Finance Regional Finance Information System.

trillion. The cumulative amount lent through SLA and RDA mechanisms from 1975 through 2004 was Rp 5.7 trillion in nominal terms or Rp 26.2 trillion in constant 2004 terms; these fi gures represent about 0.2% and 0.9% of 2004 GDP, respectively.16

While aggregate on-lending to national governments has not been sub-stantial, it does constitute the vast bulk of such lending to sub-nationals. There has been only a very small amount of lending from other fi nancial institutions, such as regional development, state, or commercial banks, and most of this has been to assist provinces and local governments in the management of cash fl ow. An early study (Lewis 1991) estimated that less than 5% of total sub-national gov-ernment borrowing was derived from sources other than the central govgov-ernment (or foreign aid agencies via the central government).

The amount of on-lending to sub-national governments and their PDAMs has varied signifi cantly over time. Figure 1 shows on-lending disbursements over the period in constant 2004 price terms. As the fi gure shows, after a relatively slow and uneven start, lending grew quickly, beginning in the mid-1980s and reaching a peak in the mid-1990s. Lending declined precipitously thereafter, and has not recovered since. Lending under the central government’s decentralisation pro-gram, which began operations in 2001, has been near zero.

Repayment of loans has been generally poor (fi gure 2). At the end of 2004, total payments due were Rp 7.1 trillion, of which only Rp 3.4 trillion had been paid—

16 By contrast, consider that the World Bank (2004) has estimated that Indonesia needs to invest around 5% of GDP annually in public infrastructure, much of which is local in character, in order to sustain a 6% medium-term economic growth target.

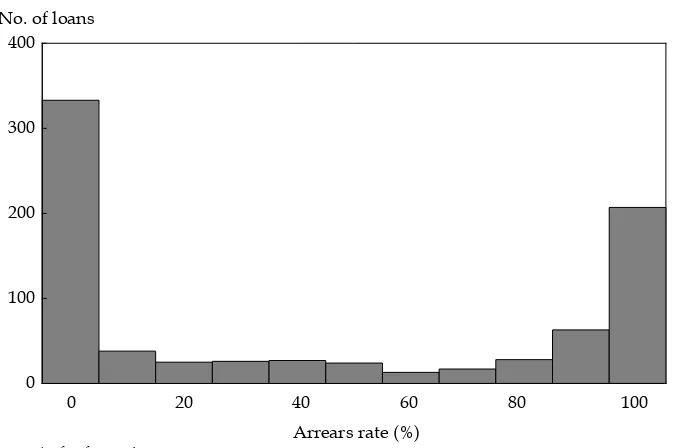

FIGURE 2 Histogram of Loans by Arrears Rate, as at 2004

Source: As for fi gure 1. 0

100 200 300 400

0 20 40 60 80 100 Arrears rate (%)

No. of loans

an arrears rate of 48%.17 Repayment varies signifi cantly across loans, however. Figure 2 shows the size distribution of loans by their respective arrears rates. On the one hand, 321 loans have been have been repaid in full and on time (including a few for which repayments exceed payments due). On the other hand, amounts due on 305 loans have been repaid only partially, and repayments on 212 loans are fully in arrears.

LOAN AMOUNTS AND LOAN PERFORMANCE: BORROWERS AND LENDERS

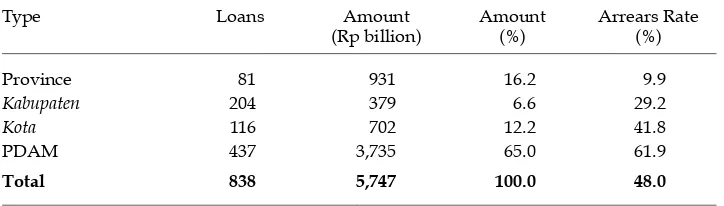

The amount of borrowing and loan repayment performance varies notably by certain borrower characteristics and by lenders. Table 1 shows the number of loans, loan amounts, and loan repayment arrears by type of borrower. Borrow-ing by PDAMs makes up the vast bulk of sub-national borrowBorrow-ing, comprisBorrow-ing nearly two-thirds of the total. PDAM loan repayments are also substantially poorer than those of other borrowers; arrears rates for PDAMs are 62%. Bor-rowing by provinces, kabupaten and kota makes up 16%, 7% and 12% of over-all amounts; arrears rates of those types of borrowers are 10%, 29% and 42%, respectively.

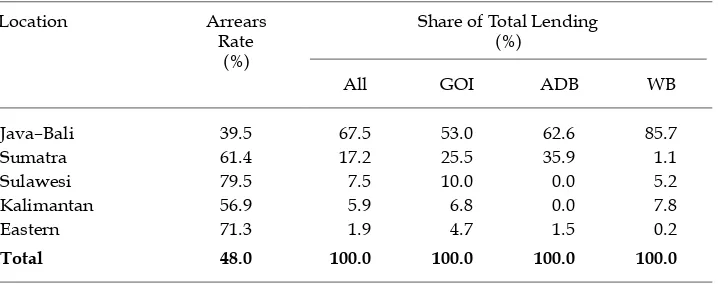

Borrowing and repayment also vary considerably by location of borrower. Table 2 provides the same information as the previous table, organised by major geographic area of borrower. Borrowing in Java–Bali has dominated, making up over two-thirds of the total amount. Borrowers on Java–Bali have also repaid their loans to a relatively better extent than those in other locations. The arrears rate of Java–Bali borrowers is about 40%. Borrowing in other geographic regions has been much more limited, and repayment performance has been signifi cantly poorer. Borrowers in Sumatra, Sulawesi, Kalimantan, and Eastern Indonesia

17 The arrears rate is equal to total payments in arrears divided by total payments due. Its use as a performance measure is standard in Indonesia. Loan repayment is not the only infrastructure fi nance outcome that matters, of course. Other important performance

indi-cators include the extent to which projects were completed and the quality of infrastructure created via the loan fi nance, for example. Unfortunately, however, there are no data on

these features of loan and project performance.

TABLE 1 Borrowing and Arrears by Type of Borrower

Type Loans Amount

(Rp billion)

Amount (%)

Arrears Rate (%)

Province 81 931 16.2 9.9

Kabupaten 204 379 6.6 29.2

Kota 116 702 12.2 41.8

PDAM 437 3,735 65.0 61.9

Total 838 5,747 100.0 48.0

Source: As for fi gure 1.

have carried out 17%, 8%, 6% and 2% of total borrowing, respectively; attendant arrears rates are 61%, 80%, 57%, and 71%, respectively.

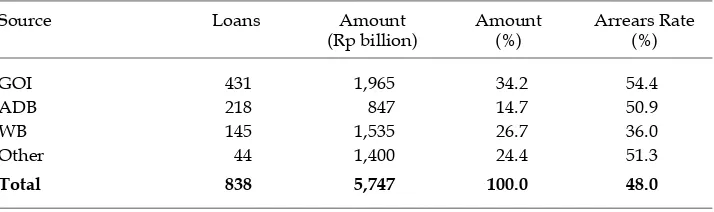

Finally, table 3 presents borrowing and arrears information by source of funds. The central government (GOI) has lent more to sub-national governments and enterprises than other lenders (34% of the total amount), followed by the WB (27%) and the ADB (15%); all other lenders combined make up about one-quarter of all lending. At 36%, the arrears rate on WB loans is noticeably lower than that on loans from other lenders. The arrears rates on ADB loans and all other aid agencies’ loans combined are both around 51% while that of loans from the cen-tral government is 54%.

The remainder of this section of the paper examines how the major lend-ers have allocated their loan fi nance across borrowers of various kinds. Among other things, this analysis may assist in explaining differences in arrears rates across lenders. It is not the contention here that lenders have selected borrow-ers with a view to optimising loan repayments; indeed it is clear that lendborrow-ers have not paid much attention at all to borrower creditworthiness in their credit allocation decisions. Nonetheless, a lender’s choice of borrowers does, inad-vertently at least, determine the overall repayment performance of loans in its portfolio.

TABLE 3 Borrowing and Arrears by Source of Funds

Source Loans Amount

(Rp billion)

Amount (%)

Arrears Rate (%)

GOI 431 1,965 34.2 54.4

ADB 218 847 14.7 50.9

WB 145 1,535 26.7 36.0

Other 44 1,400 24.4 51.3

Total 838 5,747 100.0 48.0

Source: As for fi gure 1.

TABLE 2 Borrowing and Arrears by Location of Borrower

Location Loans Amount

(Rp billion)

Amount (%)

Arrears Rate (%)

Java–Bali 418 3,881 67.5 39.5

Sumatra 239 990 17.2 61.4

Sulawesi 116 429 7.5 79.5

Kalimantan 41 341 5.9 56.9

Eastern 24 107 1.9 71.3

Total 838 5,747 100.0 48.0

Source: As for fi gure 1.

Table 4 shows lender allocation of fi nance across borrower types. As the table shows, the WB allocates a substantially higher percentage of its fi nance to prov-inces (22%) than the ADB (2%) and a signifi cantly lower percentage of its loan portfolio to PDAMs (51%) than either the ADB (67%) or the government (62%) does. That is, compared with other lenders, the WB allocates a higher percentage of its funds to borrowers with the best repayment records (provinces) and a lower percentage to those with the worst repayment histories (PDAMs).

Table 5 provides information on the distribution of lender portfolios across borrower locations. The table shows that WB lending has been concentrated in Java–Bali to a relatively larger extent (86%) than either ADB (63%) or govern-ment lending (53%). Note also that WB lending to borrowers on Sumatra has been insignifi cant (1% of total amounts), whereas both ADB and the government have devoted substantial proportions of their loan fi nance to such borrowers (36% and 26%, respectively). As shown in the fi rst column of the table, sub-national gov-ernment and enterprise borrowers in Java–Bali have repaid relatively better than others, while those in Sumatra have repaid their loans less well.

TABLE 5 Lender Allocation of Finance across Borrower Locations

Location Arrears

Rate (%)

Share of Total Lending (%)

All GOI ADB WB

Java–Bali 39.5 67.5 53.0 62.6 85.7

Sumatra 61.4 17.2 25.5 35.9 1.1

Sulawesi 79.5 7.5 10.0 0.0 5.2

Kalimantan 56.9 5.9 6.8 0.0 7.8

Eastern 71.3 1.9 4.7 1.5 0.2

Total 48.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

Source: As for fi gure 1.

TABLE 4 Lender Allocation of Finance across Borrower Types

Type Arrears

Rate (%)

Share of Total Lending (%)

All GOI ADB WB

Province 9.9 16.2 19.3 2.1 22.0

Kabupaten 29.2 6.6 9.3 12.9 5.6

Kota 41.8 12.2 9.4 17.8 21.9

PDAM 61.9 65.0 62.0 67.2 50.5

Total 48.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

Source: As for fi gure 1.

In summary, whatever the underlying reasons, the WB has been more inclined than the government and the ADB to focus its allocations on borrowers that repay relatively well. The overall conclusion, however, must be that government and foreign aid agencies alike have not allocated infrastructure fi nance as a function of the creditworthiness of borrowers to a satisfactory extent; nor have they paid suffi ciently close attention to collection of loan repayments.

PROGNOSIS FOR ON-LENDING

AND ALTERNATIVE MARKET-BASED METHODS

The government has recently put in place a new regulatory framework for sub-national borrowing, in general, and for on-lending, in particular.18 Major international aid agencies have supplied substantial resources to support the development of the new framework, especially as concerns on-lending. Success in improving the performance of on-lending will depend on the extent to which the new system is able to correct current shortcomings. In this regard, the analysis above highlighted fi ve particular and inter-related areas of concern that warrant attention: supply driven project development and fi nance; time-consuming loan approvals; the limited volume of funds channelled through the system vis-à-vis

infrastructure fi nance needs; inattention to credit risk in the allocation of fi nance; and poor repayment of loans.

New regulatory system for sub-national borrowing and on-lending

The new regulatory framework lays out the basic principles of sub-national bor-rowing and on-lending. At the broadest level it covers, among other matters, sources, types and uses of borrowing; conditions and limits on borrowing; and attendant reporting requirements. A brief description of the main principles of the new regulatory system follows.

Sub-national units may borrow from the central government, from other sub-nationals, from domestic banks and non-bank fi nancial institutions, and from Indonesian citizens. Borrowing from the central government includes that via aid agency on-lending. Borrowing from citizens is intended to refer to the issue of sub-national bonds.

Types of borrowing include short-term borrowing (maturities shorter than one year), medium-term borrowing (maturities longer than one year but less than the remaining term in offi ce of the executive of the borrowing sub-national govern-ment), and long-term borrowing (maturities longer than one year and extending beyond the term of the executive). Borrowing uses are tied to types. Short-term, medium-term and long-term borrowing are to be used, respectively, for cash fl ow management, fi nance of infrastructure that does not directly generate revenues, and fi nance of infrastructure that does directly generate revenues.

18 The new legal framework is effectively provided by Law 33/2004 on Intergovernmen-tal Finance, Government Regulation 54/2005 on Regional Borrowing, and two ministerial decrees, including one for the submission and review of project proposals and one related to rules and regulations for on-lending. The new system as codifi ed in these legal

instru-ments supplants the old framework, which was developed in conjunction with the initia-tion of Indonesia’s decentralisainitia-tion program, launched in 2001.

Limits and other conditions placed on borrowing include both ‘micro’ and ‘macro’ restrictions. Micro restrictions apply to the amounts that may be borrowed by any individual sub-national government. Outstanding debt of a sub-national government may not exceed 75% of the previous year’s general revenues. In addi-tion, a sub-national government’s debt service coverage ratio (defi ned as general revenues net of civil servant salaries and local parliament expenditures divided by debt service obligations) must be at least 2.5. Finally, a sub-national government may not borrow if it is in arrears on its debt repayments to the central government.

Sub-national borrowing must also comply with certain macro aggregate restric-tions. There are two such limits. Consolidated public sector debt must not exceed 60% of GDP, and the consolidated public sector annual defi cit (which may be fi nanced by borrowing) must not exceed 3% of GDP. The central government may use the above aggregate restrictions to set overall borrowing limits for provinces and local governments, as well as those for individual sub-national governments (i.e. above and beyond those described in the preceding paragraph) if it sees fi t to do so.

In addition to the above borrowing restrictions, other conditions apply to sub-national government borrowing. Sub-sub-national governments are prohibited from borrowing directly from foreign sources, and they must receive the approval of their parliaments to engage in medium- and long-term borrowing. Importantly, sub-national units are prohibited from pledging their revenues or assets to guar-antee loans. An exception to the latter concerns the issue of bonds; sub-nationals may use the asset constructed via bond fi nance, and pledge associated revenues, as security. Lastly, sub-national governments may not guarantee the loans of third parties (such as their water enterprises, for example).19

Finally, the regulatory framework stipulates certain reporting requirements related to sub-national borrowing. Sub-national governments are required to report their debt positions and other fi nancial information twice each fi scal year both to their parliaments and to the central government. No provisions have yet been made for sub-nationals to disclose their fi nancial positions to other than the central government and local parliaments. Neither the central government nor local parliaments make such data publicly available.

Sub-national governments that contravene any of the above principles are subject to sanctions. In particular, the centre may ‘intercept’ (i.e. delay or cut) a region’s intergovernmental transfers if it fails to comply with restrictions and other conditions. The central government may also intercept a sub-national gov-ernment’s transfers if it fails to make repayments on loans that it has taken from the centre (this applies only to loans taken out since 2001).

In terms of attempting to improve on-lending outcomes, four features of the new framework stand out. The fi rst relates to the new mechanism for submitting and reviewing project proposals and approving loans. This is referred to as the ‘blue book’ system, named after the document that contains the current list of projects that have been reviewed by the National Development Planning Agency, Bappenas, and deemed ready for implementation. Under the emerging system,

19 Law 33/2004 also asserts that the central government will not guarantee revenue bonds issued by sub-national governments. The centre continues to provide a sovereign guaran-tee for aid agency on-lending.

both sub-national governments and central departments may develop on- lending project proposals. Provinces and local governments submit project proposals directly to Bappenas for initial review. Central departments may also put forward on-lending project proposals, although they must coordinate their submissions with relevant sub-national governments. But the fact that central departments may initiate proposals for local projects to be fi nanced by on-lending raises the concern that a supply orientation in project development may still obtain under certain circumstances.

After project proposals are reviewed and the blue book is issued, a variety of additional tasks must be undertaken and completed before implementation can begin. A decision must be made as to which projects in the blue book should be prioritised to start in the given fi scal year; sub-national governments must make formal proposals to secure fi nance and those proposals must be evaluated; sub-nationals must demonstrate that they have satisfi ed a number of government ‘readiness criteria’;20 aid agency loans must be negotiated and agreement reached; and sub-loan agreements (with the sub-national borrower) must be drawn up. Bappenas, MOF and the Ministry of Home Affairs, as well as relevant technical departments, are all involved at various stages in the process. A recent review of the new system (Lewis and White 2005) concluded that while it may, in fact, represent an improvement over its predecessor, signifi cant delays in the develop-ment of sub-national on-lending projects and the disbursedevelop-ment of funds are likely to remain the norm.

Second, as noted above, the new arrangements insist that any long-term lend-ing to sub-national governments may only be used to fi nance public infrastruc-ture that directly yields revenues for sub-national government budgets. This stipulation will necessarily limit potential lending to sub-national governments to levels lower than might be justifi ed and than might otherwise be achieved.21 The requirement is arguably wrong-headed. Sub-national governments should be permitted to borrow to fi nance public capital development regardless of whether the infrastructure that is created generates revenues directly or not, as long as they have the ability and willingness (as demonstrated by past repayment experi-ence, for example) to repay. To disallow on-lending as a means of fi nancing non-revenue generating public infrastructure suggests that such infrastructure would have to be fi nanced either through own sources or through intergovernmental grants instead. The use of these funding sources is less satisfactory from adequacy, effi ciency and equity points of view.

The third pertinent characteristic of the new framework concerns the existence of repayment arrears of potential sub-national government and water enterprise

20 Sub-national borrowers must ensure that project performance indicators are in place and necessary data to measure them available; that local counterpart funds for the fi rst

year of the project have been allocated in the relevant year’s budget; that land procure-ment and/or resettleprocure-ment plans, to the extent they are needed, have been fi nalised; that

project management and project implementation units have been formed; and that project management plans and guidelines have been prepared.

21 The fact that the government has not precisely defi ned what kinds of projects are

‘directly revenue generating’ compounds the problem; while it has promised to produce a list of such projects, it has not yet done so.

borrowers. Specifi cally, government and aid agencies will only be allowed to lend to those provinces and local governments without arrears on repayments of past loans from the central government. And lenders may only lend to PDAMs as long as both the PDAMs and their associated local governments are free of arrears on prior SLA or RDA loans. Insisting that potential borrowers be free of arrears before they are allowed to borrow is a useful pre-condition from the point of view of encouraging government and aid agencies to lend to creditworthy borrowers. It essentially forces lenders to pay more attention to credit risk, albeit in a some-what crude fashion.

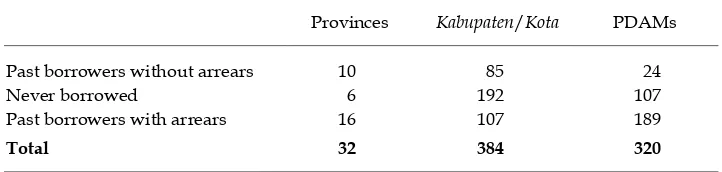

Based on the no-arrears criterion, two types of potential sub-national govern-ment borrowers immediately present themselves: those that have borrowed and have repaid their obligations in full and those that have never borrowed. There are just 95 sub-national governments (10 provinces and 85 local governments) that have borrowed from the centre in the past and that are free of arrears. The second group is signifi cantly larger than the fi rst: 198 sub-national governments have never borrowed (six provinces and 192 local governments). The situation is slightly more complicated for water enterprises. As noted, both PDAMs and their associated sub-national governments must be free of arrears before the former would be allowed to borrow. There are only 24 PDAM past borrowers without arrears and eight of their respective local governments have repayment arrears on past loans from government. On the other hand, 107 PDAMs have never taken out a loan; seven of their associated local governments have borrowed from the centre and are in arrears on loan repayments. These data are summarised in the fi rst two rows of table 6.

If on-lending to sub-national governments is to be suffi ciently increased it will not be adequate to rely on past borrowers with good repayment records; sub-national governments and enterprises that have never borrowed will need to be encouraged to do so. In the present environment, the extent to which this is possible is quite unclear. The government has no plan in place to stimulate credit demand among sub-national units that have no experience with borrowing.

Increasing the number of potential borrowers further would require that those sub-national governments and water enterprises with repayment arrears on past loans clear away those arrears (see the third row of table 6). There are 123 sub-national government borrowers with arrears (16 provinces and 107 local governments); in addition, there are 189 PDAM borrowers with arrears (and an additional associated 93 local government borrowers with arrears).

TABLE 6 Classifi cation of Potential Sub-national Borrowers

Provinces Kabupaten/Kota PDAMs

Past borrowers without arrears 10 85 24

Never borrowed 6 192 107

Past borrowers with arrears 16 107 189

Total 32 384 320

Source: As for fi gure 1.

Two plausible means exist for sub-national governments and their enterprises to eliminate their loan repayment arrears. First, sub-national governments could use their accumulated unspent revenues, or ‘reserve funds’, to pay off their (and their water enterprises’) arrears immediately. Second, sub-national borrowers could have their debt repayment obligations (including any arrears) restructured, rescheduled or written off by the central government.

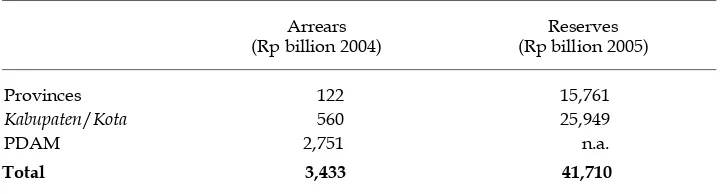

Sub-national governments have substantial reserve funds. By the end of 2005, provinces and local governments together had accumulated about Rp 41.7 trillion in reserves.22 By contrast, total provincial, local government and PDAM repay-ment arrears amounted to only around Rp 3.4 trillion (at the end of 2004) (table 7). In the aggregate therefore, provinces and local governments would appear to have more than enough funds to clear away easily the entire stock of sub-national government and water enterprise arrears.23

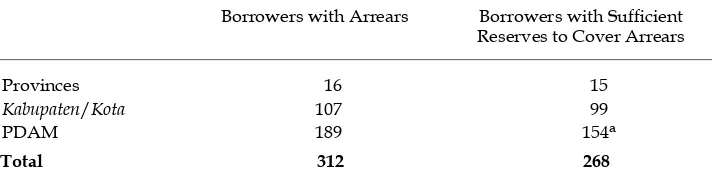

The aggregate data offer only an approximate appraisal of the extent to which sub-national government reserves might be used to cover repayment arrears, however. A more accurate picture of the suffi ciency of reserves to cover arrears would be provided by a comparison of reserves with arrears at the individual sub-national government level (table 8).

As the table shows, most individual sub-national governments have suffi cient reserves to cover their arrears and those of their water enterprises. Over 85% of individual borrowers could have their arrears cleared away by the relevant sub-national government’s stock of reserves. Of course, sub-sub-national government

22 The sub-national stock of reserves at the end of 2005 amounted to about 21.5% of total sub-national expenditure that year and approximately 1.6% of GDP (in 2005). As of the end of November 2006, sub-national government reserves had grown to Rp 95 trillion. 23 The magnitude of such reserves may raise the question as to why sub-national govern-ments should bother to borrow at all, when they could simply use their reserves to fi nance

infrastructure. Such reserve funds could, in fact, appropriately be used to fi nance capital

expenditure, of course. But reserves might legitimately be required for other purposes as well, including addressing cash fl ow problems and contingency or emergency needs (Tyer

1993). This suggests that it would not be prudent for sub-national governments to use the entire stock of their reserves to fi nance public capital development.

TABLE 7 Aggregate Borrower Arrears and Reserves

Arrears (Rp billion 2004)

Reserves (Rp billion 2005)

Provinces 122 15,761

Kabupaten/Kota 560 25,949

PDAM 2,751 n.a.

Total 3,433 41,710

n.a. = not applicable.

Source: As for fi gure 1.

willingness to use reserves in such a manner cannot be guaranteed. The reasons for such unwillingness are surely varied. Without doubt sub-national govern-ments benefi t from the interest earnings on their stocks of reserves. In some cases, sub-nationals might have legitimate alternative expenditure plans for such funds. Finally, while there is (as yet) no direct evidence of specifi c corrupt practices asso-ciated with reserve funds, clearly this is a possibility, given the insuffi cient con-trols that exist at the sub-national level.

While the central government is aware of the general issue, offi cials have not yet thought much about how they might encourage sub-nationals to use their reserves to pay off their stocks of arrears. Indeed, in the new decentralised envi-ronment it is not clear what the government could do to stimulate use of reserves in this way, barring a decision directly to mandate some action by legal means. Such an act would certainly prove highly controversial; it is probably politically infeasible.

Separate from new on-lending arrangements, the central government has recently authorised covering legislation that provides the beginnings of a frame-work for restructuring, rescheduling and writing off loan repayments associated with PDAM debt. Technical guidelines for the PDAM debt work-out agenda are currently being prepared, but implementation has not yet begun. Similar legisla-tion for provincial and local government debt work-outs is planned, but relevant work has not yet commenced.

The fi nal feature of the regulatory environment of interest concerns the ernment’s intergovernmental transfer intercept mechanism. As noted above, gov-ernment may cut any sub-national’s transfers if it fails to meet loan repayment obligations to the centre. Actually, this is not a new attribute of the intergovern-mental framework; the intercept has been in place since 2001. The main problem with the tool is simply the government’s apparent and unfortunate reluctance to employ it: there have been numerous instances since 2001 when the government might have legitimately used the transfer intercept, but so far it has chosen not to do so.

In summary, it would not appear that the new regulatory framework for on-lending will be of much assistance in facilitating improved on-on-lending perform-ance. The new project review and loan approval process provides some rather

TABLE 8 Individual Borrower Arrears and Reserves

Borrowers with Arrears Borrowers with Suffi cient

Reserves to Cover Arrears

Provinces 16 15

Kabupaten/Kota 107 99

PDAM 189 154a

Total 312 268

a Local government reserves suffi cient to cover both PDAM arrears and any arrears of local govern-ments.

Source: As for fi gure 1.

unfortunate scope for central departments to force the development of local projects that they consider are of the highest priority (but that sub-nationals may not). In any case, it is likely to remain cumbersome and time consuming. The amount of fi nance channelled through the system is likely to remain signifi cantly lower than is justifi ed, at least in part because on-lending is restricted to fi nancing revenue generating projects. While the new framework forces lenders to pay more attention to credit risk, by lending only to those sub-national entities without arrears on past loans the government is doing little to increase the number of such creditworthy borrowers and stimulate demand for credit. And fi nally, although the government has at its disposal a tool to encourage better repayment of loans that it makes, it has so far proved unwilling to employ the mechanism.

Developing market-based approaches to sub-national credit

Ultimately, what is probably needed to improve the performance of lending to sub-national governments is the adoption of approaches that rely less on direct government (and aid agency) involvement and that are more market oriented. At least it is commonly argued that market-based lending mechanisms lead to more successful sub-national infrastructure fi nance outcomes than on-lending does (Peterson 1996; Freire and Petersen 2004; Martell and Guess 2006). Any new market-based system would also be constrained by some of the same features of the general environment noted above as being problematic in the context of on- lending, however. The dearth of creditworthy sub-national governments, for example, is a diffi cult issue that any new system would have to confront as well.

One positive feature of the new regulatory framework is that sub-national gov-ernments are now allowed to issue bonds. This will certainly help pave the way for more market-based approaches to sub-national fi nance, although the exclu-sive focus on revenue bonds (as opposed to general obligation bonds) will limit potential positive impact. Other aspects of the new regulatory environment will prove especially challenging for the development of a market-based system of sub-national credit. There are three important issues in this regard.

First, arrangements concerning security for sub-national loans are likely to remain problematic. As mentioned above, sub-national governments are explicitly prohibited by law from pledging their revenues or assets to secure loans, except in the case of revenue bonds. Regarding the latter, sub-national government issu-ers may employ revenues generated by the asset created via the bond fi nance (as well as the asset itself) as security, but they may not, apparently, pledge any of their other revenues or assets to secure bonds. Finally, sub-national governments may not guarantee the loans (bonds or otherwise) of third parties, including, in particular, their PDAMs.

Second, defi cient sub-national government fi nancial reporting and disclosure remain a source of concern. While sub-national governments are obligated by law to report certain fi scal and fi nancial information to the central government, many do not do so. Sometimes this is because they lack the capacity to produce the requested data and therefore are essentially unable to comply. The centre requires sub-nationals to submit balance sheets, for example, but sub-national govern-ments do not as a rule construct balance sheets. In other cases, sub-national gov-ernments possess the required information, such as that related to (short-term) borrowing from commercial banks, but simply refuse to report it to the centre,

while the central government has proved reluctant to employ available sanctions in order to force sub-nationals to comply. A related problem concerns the reliabil-ity of information reported to the centre. Consider central requests regarding sub-national budget realisations, for instance. Sub-sub-national governments, of course, generate realised budgets and they are legally required to have budget realisa-tions audited at the end of the fi scal year. However, most sub-nationals do not have their budget out-turns externally audited, as required by law. Among other things, this raises a concern about the accuracy of sub-national budget informa-tion that is supplied to central government. Finally, sub-nainforma-tional governments are not obliged to disclose fi scal and fi nancial information to the public, and the vast majority of sub-nationals do not make such information available.

Third, strong methods to address severe problems related to fi scal distress and insolvency at the sub-national level do not exist at present. The new regulatory framework makes no provisions for forced budget interventions or for the default or bankruptcy of sub-national governments, for example. The central government has expressed general interest in developing the needed arrangements but, again, nothing has been accomplished as yet.

Most of the above constraints are not insurmountable, given suffi cient politi-cal will. This suggests that success in further developing new market-based approaches would depend, more generally, on the extent of government and aid agency appetite for such reform. The proposition that a more market-based credit system for sub-national governments is needed is not new in Indonesia. Various relevant concepts and proposals have been discussed for more than 15 years. And many offi cials inside the government and aid community have expressed interest in such mechanisms in the past. Discussions were essentially put on hold, how-ever, after the East Asian fi nancial crisis.

It now seems that the government may have a renewed interest in consider-ing more market-based approaches to fi nancing sub-national infrastructure. Most programs being discussed involve developing sub-national government access to private capital markets via the issue of bonds; the inherent risks associated with sub-sovereign debt obligations would be mitigated through the use of compre-hensive or partial guarantees, co-fi nancing and subordination, pooled fi nancing, secondary market liquidity support, and other similar techniques (Kehew, Matsu-kawa and Petersen 2005). There would appear to be rather wide support inside government, at least, for the idea of moving ahead in this general direction. This is not the place to discuss the merits of various methods in depth, however.

In closing this section of the paper, it might be useful to mention two points. First, such a new system would take a considerable amount of time to create. One could not envision comprehensive and operational mechanisms in place for several years, even after an explicit decision to initiate some concerted action. Second, the adoption of such schemes would imply very different roles for both government and aid agencies from the ones that they play now. At present, both parties assist in the development of local projects and directly provide project fi nancing. In the new environment, government and aid agencies would prob-ably have much more indirect fi nancial responsibilities. In this regard, they might provide contingent or parallel loans, or offer partial credit guarantees, for exam-ple (Kehew, Matsukawa and Petersen 2005). The function of foreign aid agencies (especially) in developing local infrastructure projects under such a new system

is, however, quite unclear. But since project development would probably be less directly linked to aid agency fi nancing, the tasks of aid agencies in designing and implementing projects might be quite different, if indeed they exist at all.24 One imagines that some foreign aid agencies might have signifi cant diffi culty in adapt-ing to such an environment, given the systems that are now in place to support the current ways of doing business.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Government and aid agencies have been involved in on-lending to sub-national governments and enterprises in Indonesia for over 30 years. The WB and the ADB have been the most noteworthy foreign participants. Most on-lending has gone to water enterprises, and a large proportion of funds has been concentrated in Java–Bali. The experience of on-lending has been rather disappointing. Project development and fi nance have at least occasionally been supply-driven. Associ-ated loan approval processes have proved cumbersome and time consuming. The amount of fi nance channelled through the system since 1975 has been rather insig-nifi cant, and on-lending has declined to near zero since decentralisation began in 2001. Lenders have paid insuffi cient attention to credit risk in fi nance allocation decisions. Overall, loan repayment has been weak; nearly 50% of payments due are in arrears.

Differences in loan performance across sources of funds appear to be mainly a function of lenders’ selection of borrowers. The investigation in this paper shows that the WB has focused a relatively larger share of its fi nance on borrowers that repay comparatively well, although it must be admitted that this was probably not done in a deliberate attempt to improve loan performance, per se. The over-all conclusion must be that lenders, in general and without exception, have not allocated infrastructure fi nance as a function of borrower creditworthiness to a satisfactory extent, nor have they paid suffi ciently close attention to the collec-tion of loan repayments. This is unfortunate. Both government and aid agencies have a responsibility to lend with a view to building sound sub-national credit markets. In this regard, engendering an environment of creditworthiness should be a goal of such lending. As such, at a minimum, government and aid agencies should focus their lending on sub-national governments and enterprises that can and will repay. And government, as the main force behind collections related to on-lending, should employ all the mechanisms at its disposal to compel repay-ment when necessary

The government has recently put in place a new regulatory framework for on-lending, but it does not appear that this will be of much assistance in facili-tating improved fi nancing outcomes. The new project development process retains some worrying vestiges of central command and control, which may lead to locally unwelcome projects and loans. Loan approval processes are likely to remain burdensome and, as such, will create further disincentives for sub-nation-als to borrow from or via the centre and, in any case, will cause delays in project

24 Law 33/2004 on Intergovernmental Finance prohibits foreign aid agencies from lend-ing directly to sub-national governments. Interestlend-ingly, this prohibition seems not to ex-tend to PDAMs.

implementation. The new system binds on-lending to revenue generating projects, thereby unnecessarily limiting the scope and volume of lending. While the frame-work forces lenders to pay more attention to credit risk by insisting that they lend only to those sub-national entities without arrears on past loans, the government is doing little to increase the number of such creditworthy borrowers or stimulate local demand for credit more generally. Finally, although the government has at its disposal a simple mechanism to encourage better repayment of loans, it has so far proved unwilling to employ this tool. As a result, loan performance is likely to remain problematic. It is hard to escape the conclusion that the near-term future of on-lending is gloomy indeed.

Actually, the collapse of on-lending might well constitute a positive develop-ment. At least this would be the case if the demise of such lending stimulated the more rapid creation and adoption of a sub-national system of credit that relies less on direct public sector involvement and that is more market oriented. Of course, any new system of fi nance would be confronted with some of the same problems as those that constrain on-lending, including the limited number of creditworthy borrowers, as well as other restrictions of a regulatory nature. Still, developing sub-national government access to private capital markets, supported by the crea-tion and use of various credit enhancements, as has been done in other countries, would appear to represent a plausible way forward. It will take time to put rel-evant institutions and techniques in place: one would not expect this to be accom-plished in less than several years time. A positive step in the right direction would be for government and aid agencies to embrace the anticipated change and work together to make the transition a successful one, rather than continue to tinker with reforms at the margin of a moribund system.

REFERENCES

Devas, Nick and Binder, Brian (1989) ‘Loan fi nance for regional development’, in Financing

Local Government in Indonesia, ed. Nick Devas, Ohio University Center for International Studies, Athens OH, chapter 8.

Development Alternatives (2002) Local government fi nance policy framework study,

Pre-pared for Republic of Indonesia, Ministry of Finance, and United States Agency for International Development, Jakarta.

Freire, Mila and Petersen, John with Huertas, Marcela and Valadez, Miguel (eds) (2004) Sub-national Capital Markets in Developing Countries: From Theory to Practice, World Bank, Washington DC.

Kehew, Robert and Petersen, John (2004) ‘Indonesia’, in Sub-National Capital Markets in Developing Countries: From Theory to Practice, eds Mila Freire and John Petersen with Marcela Huertas and Miguel Valadez, World Bank, Washington DC.

Kehew, Robert, Matsukawa, Tomoko and Petersen, John (2005) Local Financing for Sovereign Infrastructure in Developing Countries: Case Studies of Innovative Domestic Credit Enhancement Entities and Techniques, World Bank, Washington DC.

Lewis, Blane (1991) Regional government borrowing in Indonesia, Harvard Institute for International Development, Urban Project, Jakarta.

Lewis, Blane (1997a) Regional Development Account portfolio analysis, Research Triangle Institute, Municipal Finance Project II, Jakarta.

Lewis, Blane (1997b) Subsidiary Loan Agreement portfolio analysis, Research Triangle Institute, Municipal Finance Project II, Jakarta.

Lewis, Blane (2003) ‘Local government borrowing and repayment in Indonesia: does fi scal

capacity matter?’, World Development 31 (6): 1,047–63.

Lewis, Blane and White, Roland (2005) ‘On-lending and on-granting donor funds in Indo-nesia: an overview and assessment of the emerging legal and regulatory framework’, World Bank Offi ce Technical Paper, Jakarta.

Martell, Christine and Guess, George (2006) ‘Development of local government debt fi

nanc-ing markets: application of a market-based framework’, Public Budgeting and Finance 26 (1): 88–119.

Oosterman, Andre (2005) Towards improved management of on-lending and on-granting, Technical Assistance for Policy Formulation on Fiscal Decentralization, World Bank Dutch Trust Fund, Jakarta.

Oosterman, Andre and Samiadji, Bambang Tata (2004) Implementing KMK 35, Technical Assistance for Policy Formulation on Fiscal Decentralization, World Bank Dutch Trust Fund, Jakarta.

Peterson, George (1996) Using municipal development funds to build municipal credit markets, World Bank, Washington DC.

Research Triangle Institute (1999) Regional Development Account institutional strengthening project fi nal report: vol. 1. Findings and conclusions, Asian Development Bank, Manila.

Tyer, Charlie B. (1993) ‘Local government reserve funds: policy alternatives and political strategies’, Public Budgeting and Finance 13 (2): 75–84.

Varley, Rob (2001) Indonesia: the Regional Development Account and alternatives for

fi nancing urban infrastructure, Asian Development Bank, Jakarta.

Weitz, Almud (2001) Options for municipal fi nance in Indonesia, Asian Development

Bank, Jakarta.

Woodward, David (2000) Loan portfolio review, Project Implementation and Institutional Support of the Regional Development Account, Asian Development Bank, Jakarta. Woodward, David (2005) Status of RDA loan portfolio review—December 31, 2004, Asian

Development Bank, Jakarta.

World Bank (2004) Averting an Infrastructure Crisis in Indonesia: A Framework for Policy and Action, World Bank, Washington DC.

APPENDIX

This appendix examines empirically the relationship between loan repayment by sub-national governments and PDAMs and a number of potentially important explanatory variables highlighted in the paper. The specifi c interest is to determine the extent to which these variables and factors help determine non-repayment of loans, when all such variables and factors are considered simultaneously. The results of the empirical analysis are presented but not discussed in great detail.

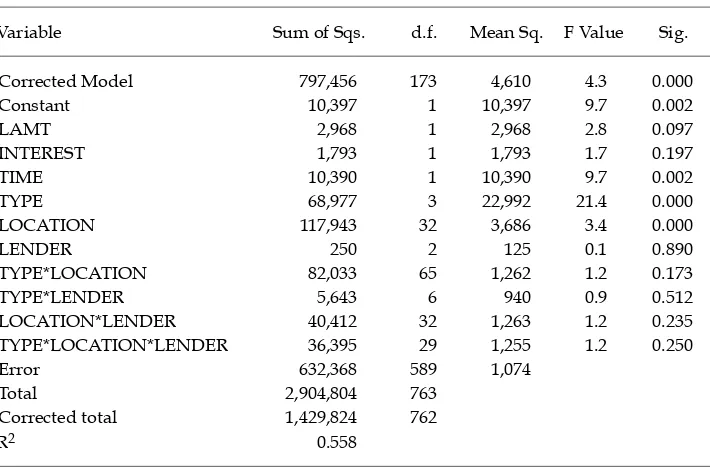

The procedure used is GLM (general linear model) general factorial analysis. The method provides an analysis of the infl uence of covariates and fi xed factors on a single independent variable. Covariates are continuous variables; fi xed factors are categorical variables that divide the population into two or more groups. The methodology allows for examination of possible interaction effects among variables. Table A defi nes the dependent and explanatory variables used in the analysis.

The conventional wisdom in Indonesia is that larger borrowers are more likely to default (although Lewis 2003 offered some empirical evidence to the contrary, at least for kabupaten and kota). Some local government offi cials argue that they do not repay their loans because interest rates are ‘too high’. Finally, there is clear evidence to suggest that, in general, loan repayment rates have deteriorated over time (Lewis 2003). Given the above, it might be expected that the arrears rate would be positively associated with (the log of) the loan amount, with the interest rate, and with the time trend variable. The analysis tests these hypotheses.

This paper has also provided some empirical evidence that loan repayment varies by type and location1 of borrower and by lender, at least when each of the variables is taken in isolation from the others. The analysis here tests the extent to which the demonstrated relationships hold when all variables are considered together. In addition to examining the infl uence of the covariates and fi xed factors outlined in table A, the analysis also considers all possible interaction effects among fi xed factors. As such, the model is a ‘full factorial’ GLM model.

As noted in table 1, 838 loans are considered in this paper. Loans made by ‘other lenders’ (a group without much analytical meaning), and a number of loans on which some data were missing, were dropped from the analysis, leaving 763 loans in the sample. Table B provides the basic results of the GLM analysis. As the table shows, neither loan size nor interest rate is a signifi cant determinant of the arrears rate. The time trend variable is, however, positively and signifi cantly associated with arrears. As expected, the type and location of the borrower are signifi cant in infl uencing the arrears rate. Perhaps surprisingly, given the basic descriptive results supplied in the text, the lender is not a signifi cant determinant of loan repayment arrears when the effects of all other variables are simultaneously considered. None of the interactions proved statistically signifi cant.2 Finally, all variables taken together explain about 56% of the variation in the arrears rate

1 The paper defi ned location as a function of major island groupings: Sumatra,

Kaliman-tan, Java-Bali, Sulawesi, and Eastern Indonesia. The analysis presented in the appendix uses the province of the borrower to defi ne location. Use of province instead of island

grouping adds signifi cantly to the explanatory power of the independent variables.

2 Standard regression coeffi cients and t statistics can be derived for the covariates and for fi xed factors, as well as for interactions. These results are not reported here but are

avail-able from the author upon request.

TABLE B General Factorial Analysis Results

Variable Sum of Sqs. d.f. Mean Sq. F Value Sig.

Corrected Model 797,456 173 4,610 4.3 0.000

Constant 10,397 1 10,397 9.7 0.002

LAMT 2,968 1 2,968 2.8 0.097

INTEREST 1,793 1 1,793 1.7 0.197

TIME 10,390 1 10,390 9.7 0.002

TYPE 68,977 3 22,992 21.4 0.000

LOCATION 117,943 32 3,686 3.4 0.000

LENDER 250 2 125 0.1 0.890

TYPE*LOCATION 82,033 65 1,262 1.2 0.173

TYPE*LENDER 5,643 6 940 0.9 0.512

LOCATION*LENDER 40,412 32 1,263 1.2 0.235

TYPE*LOCATION*LENDER 36,395 29 1,255 1.2 0.250

Error 632,368 589 1,074

Total 2,904,804 763

Corrected total 1,429,824 762

R2 0.558

TABLE A Variable Names and Defi nitions for General Factorial Analysis

Variable Name Description

Dependent variable

RATE Arrears rate: loan payments in arrears divided by payments due, times 100

Covariates

LAMT Logarithm of loan amount (Rp billion) INTEREST Interest rate on loan (% p.a.)

TIME Time trend: year loan was made minus 1974

Fixed factors

TYPE Type of borrower: province, kabupaten, kota, PDAM

LOCATION Provincial location of borrower: Aceh, North Sumatra, West Sumatra, Riau, Jambi, South Sumatra, Bengkulu, Lampung, Jakarta, West Java, Central Java, Yogyakarta, East Java, West Kali-mantan, Central KaliKali-mantan, South KaliKali-mantan, East KaliKali-mantan, North Sulawesi, Central Sulawesi, Southeast Sulawesi, South Sulawesi, Bali, East Nusa Tenggara, West Nusa Tenggara, Maluku, Papua, North Maluku, Banten, Kepulauan Bangka Belitung, Kepu-lauan Riau, Gorontolo, West Sulawesi, West Papua

LENDER Lender: Government of Indonesia, Asian Development Bank, World Bank