Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 18 January 2016, At: 00:28

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Modelling the influence of caring for the elderly on

migration: estimates and evidence from Indonesia

Anu Rammohan & Elisabetta Magnani

To cite this article: Anu Rammohan & Elisabetta Magnani (2012) Modelling the influence

of caring for the elderly on migration: estimates and evidence from Indonesia, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 48:3, 399-420, DOI: 10.1080/00074918.2012.728652

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2012.728652

Published online: 20 Nov 2012.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 195

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/12/030399-22 © 2012 Indonesia Project ANU http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2012.728652

MODELLING THE INFLUENCE OF

CARING FOR THE ELDERLY ON MIGRATION:

ESTIMATES AND EVIDENCE FROM INDONESIA

Anu Rammohan* Elisabetta Magnani*

University of Western Australia University of New South Wales

In a society where children are expected to support the elderly, the ill health of an elderly parent is likely to inluence an individual’s propensity to migrate. Using data from the Indonesian Family Life Survey, we examine the manner in which the responsibility to care for an elderly parent who is in poor health affects the migration decisions of working-age adults. Our analysis suggests that individuals will be less likely to migrate if they have elderly parents who are in poor health. These indings are robust to speciications using alternative measures of poor health.

Keywords: migration, caregiver, caregiving, care of the elderly, Indonesia

INTRODUCTION

In many developing countries, a lack of social safety nets means that the respon-sibility to care for elderly parents falls mainly on family members. The conse-quences of such caregiving for the migration decisions of working-age adults are not well understood, however. The early literature on migration focused on

fac-tors inluencing the likelihood of migration, at both the individual and household levels (see, for example, Harris and Todaro 1970; Borjas 1989). Studies by Lanzona (1998) and Agesa (2001) showed that factors such as the scarcity of jobs in rural

areas and the higher incomes that could be earned in urban areas were important in persuading ‘surplus’ low-skilled workers as well as ‘scarce’ educated workers to move to the cities. Studies such as these have treated migration as an economic decision in response to wage differentials in rural–urban settings.

In an early paper, Mincer (1978) argued that family ties may have a deterrent effect on the decision to migrate, and since the mid-1980s, when Stark and Bloom

(1985) introduced their ‘new economics of labour migration’, the inluential role of

*[email protected]; [email protected]. We are grateful to participants at the Australasian Development Economics Workshop (Canberra, 2008) and the Popula -tion Associa-tion of America meetings (Detroit, 2009) for useful comments on earlier drafts of this paper, and to Marie-Claire Robitaille for excellent research assistance. The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the Australian Research Council Discovery Project grants scheme.

the family in migration decisions has been studied extensively.1 A large literature on developing countries emphasises the role of family ties in migration, showing

that patterns of resource lows from individuals in urban areas to families in rural

areas are largely consistent with strategies to diversify the household’s sources of income and thus reduce the precariousness of rural life.2 These studies suggest that migration decisions are made in a familial context. They typically focus on the role of remittances from adult children living in the cities to family members left behind in the countryside. In addition to economic support, however, elderly family members will often require physical care, particularly if they fall ill.

In China, migration has been found to be beneicial for rural households and migrantsending villages. These beneits can take the form of higher levels of household income (Taylor, Rozelle and De Brauw 2003); a greater ability on the part of households to manage risk (Giles 2006; Giles and Yoo 2007); a reduction in rural income inequality (Benjamin, Brandt and Giles 2005: 807); and the likelihood

of higher levels of local investment in productive activities (Zhao 2002). An inabil-ity to migrate because of caregiving responsibilities can therefore be detrimental not only to working-age adults, but to their families and communities.

In most Asian countries, social safety nets for the elderly are patchy or non-existent, and the family is an important source of informal care. This undoubtedly affects the ability of working-age adults to migrate, especially if the parents are unwell. We are aware of only two studies for developing countries, however, ana-lysing the links between the migration decision and the health of family members. Muhidin (2006) studied the effect of migration on the health of household mem-bers remaining in the countryside, using data from the 1993 and 1997 rounds of the Indonesian Family Life Survey (IFLS) – that is, earlier versions of the datasets used in this paper.3 Giles and Mu (2007) examined the impact of illness among elderly parents in China on the propensity of adult children to migrate. Both studies found that poor health among family members was an impediment to migration by adult children. Kreager (2006) points out, however, that the impact of migration on support networks for the aged in Indonesia has not been analysed systematically.

Based on data from the 2000 and 2007–08 rounds of the IFLS, this paper aims to address the following three questions. Does the need to care for an elderly parent affect the propensity to migrate? How does the availability of alternative sources

of care (in the Indonesian case, chiely other siblings living nearby) affect the

migration decisions of working-age adults? And what effect does the gender of the caregiver have on the propensity to migrate? We argue that in an environment

1 While there are many studies on the network externalities from migration – that is, on the importance of social networks and family ties in fostering migrant networks – this issue is beyond the scope of the present study.

2 See, for example, Lucas and Stark (1985); Leinbach and Watkins (1998); Chen, Chiang and Leung (2003); Frankenberg and Kuhn (2004); and Giles and Yoo (2007).

3 The IFLS is a longitudinal survey conducted in Indonesia by the Rand Corporation in collaboration with local partners. The sample covers over 30,000 individuals living in 13 of Indonesia’s 27 provinces, and is representative of about 83% of the population. The lat-est (third and fourth) rounds of the survey were conducted in 2000 and 2007–08. For more information, see <http://www.rand.org/labor/FLS/IFLS.html>.

where adult children are required to support their parents, the ill health of an

elderly parent is likely to inluence the propensity of an individual to migrate.

Our focus on Indonesia is motivated by several factors. First, Indonesia still has substantial rural poverty, high levels of rural–urban migration and a largely family-based, informal system of aged care. As in the rest of Asia,4 co-residence between elderly parents and at least one adult child is a central feature of the familial support system in Indonesia, with social sanctions imposed on adult children who do not care for their elderly parents (Cameron 2000). Governments across Asia actively encourage this family-oriented support system for the elderly (Chan 1997), with few moves made to set up universal social safety nets.

Second, families and communities are still expected to provide the bulk of social insurance in Indonesia. Although the government invested heavily in health and education during the 1980s and 1990s, and set up a compulsory social security program for formal sector employees, most Indonesians still do not have access to pensions and need to make their own provisions for retirement and old age. The government has also instituted a wide range of programs targeting poor and

nearpoor Indonesians since the Asian inancial crisis in 1998 (Sumarto, Surya

-hadi and Widyanti 2004: 3–8), but very few of them speciically target the elderly.

Finally, the Indonesian population is ageing rapidly. With little in the way of social safety nets for the elderly, this will constrain the ability of working-age children with unwell elderly parents to migrate. The issue of population ageing in Indonesia is compounded by poverty among the aged. The elderly have little access to public pension programs, which are limited to employees in the public

sector, or are modest (Leechor 1996; ILO 2003: 90; Ariianto 2005).

In the next section, we describe the living arrangements of the elderly and the patterns of migration in Indonesia. This is followed by a description of the paper’s modelling strategy and dataset. We then present the main results from the analysis.

BACKGROUND

In Indonesia, family sizes are shrinking, the population is ageing, and the nature of the health problems being experienced by the elderly is changing. These demo-graphic changes are occurring against a background of high economic growth and a continuing exodus of rural Indonesians to the cities, or even overseas, in search of employment and other opportunities.

Indonesia has experienced a sharp decline in fertility, with the average number

of children born per woman declining from 4.5 in 1980 to 2.2 in 2009 (OECD 2011:

19). The population aged 60 years or older is expected to rise dramatically over

the next few decades. By 2050, Indonesia is expected to have 72 million individu -als aged 60 years and above, and will be one of only six countries in the world with over 10 million people aged 80 years and above (UN 2009: 10, 24). This rapid ageing of the population is expected to induce a drop in the share of working-age adults as a percentage of the total population at a time when the health care needs of elderly Indonesians will be rising.

4 See, for example, Kim and Choe (1992); Knodel, Saengtienchai and IngersollDayton (1999); and Bongaarts and Zimmer (2001).

According to Van Eeuwijk (2006: 61–2), Indonesia is experiencing a ‘health

transition’ in which the most prevalent diseases among the elderly are chronic,

noninfectious illnesses and injuries rather than acute infectious diseases. In con -trast to the health transitions experienced in Europe and North America in the

second half of the 19th century, the changes in the health proile of the Indonesian

population are happening very quickly, and are affecting large numbers of peo-ple. The challenges of coping with an ageing population requiring long-term care to manage chronic diseases are exacerbated by the absence of a well-functioning

public health care system (UNDP 2010).

These changes to family structure and to patterns of work and retirement pose immediate economic challenges, particularly to the social insurance system, which is not designed to deal with an ageing population. Currently the pension and social insurance system covers only formal sector workers and the very poor. The lack of social safety nets for the elderly increases the vulnerability of older people to poor health and poverty. This raises the question of who will care for the growing numbers of elderly as the population ages.

More than half the elderly population lives in rural areas, with Java having the highest proportion of elderly individuals. In our dataset, the elderly generally tend to be less well educated than younger cohorts. However, labour force par-ticipation among the elderly is reasonably high, with nearly 43% of those aged 70

years or above working up to 32 hours per week. This is consistent with the ind -ing by Cameron and Cobb-Clarke (2008: 1,013) of high levels of labour force par-ticipation among elderly Indonesians. But it is nevertheless somewhat surprising considering Indonesia’s large pool of surplus labour: in 2006, approximately 11% of Indonesian workers were unemployed, and over 20% were under-employed (Hugo 2007).

Migration trends in Indonesia

An exodus of rural dwellers to the cities has been under way in Indonesia for sev-eral decades. Between 1971 and 2000, the proportion of the population living in urban areas rose from 17% to nearly 42%, while the urbanisation rates in the most attractive destinations for migrants – the provinces of Jakarta, West Java,

Yogya-karta, Bali and East Kalimantan – rose to 50% or higher (Rogers et al. 2004: 4).

In the Indonesian context, circular migration (merantau) is fairly common, with seasonal migrants helping to diversify sources of rural household income by send-ing back remittances (Nas and Boender 2002). The children of such migrants are usually left at home to be cared for by grandparents and other family members.

Miguel, Gertler and Levine (2006: 297) ind that an improvement in employ -ment prospects in a ‘nearby’ district (one located within 200 kilometres of the

district capital) is associated with higher levels of outmigration, with just over

half of all migrants moving to other districts within the same province. Accord-ing to Kreager (2006: 40), migration within Indonesia is dominated by

individu-als aged 15–29, with the majority of migrant moves made by those aged 20–24.

Although the remittances that younger family members send home do help to diversify rural families’ sources of income and to spread risk, there are also some drawbacks. Migration by working-age adults may increase the vulnerability of older family members if, for example, remittances are not forthcoming, grandchil-dren are left in their care, assets have to be sold to fund a child’s departure, or a

member of the family becomes ill and requires physical care (SchröderButterill 2004; Kreager 2006).

Increasingly, many Indonesians are choosing to go abroad to work. Accord-ing to Hugo (2007), international migration by Indonesians takes two forms. The

irst is migration to more developed nations, particularly those belonging to the

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). This type of migration tends to be permanent and is dominated by skilled migrants. The sec-ond is the better-known, temporary movement of largely unskilled workers to the Middle East and other parts of Asia. In mid-2006, the Minister of Manpower and Transmigration reported that 2.7 million Indonesians (2.8% of the total workforce)

were working overseas with oficial permission. Of these, 83% were women, the

bulk of them working in the informal sector as housemaids, and the remainder as daily wage labourers, caregivers to the elderly, shop assistants or waitresses (World Bank 2006).5

MODELLING STRATEGY

Our goal is to examine the manner in which the responsibility to care for an elderly parent who is in poor health affects the migration decisions of adult children. The empirical strategy is derived from a simple theoretical model of household labour

supply. Assume a ixed total time endowment (T) is allocated between alternative

uses, namely participation in the labour market; caregiving (CG); and a residual, leisure time (L). A working-age adult chooses to allocate hours optimally so as to maximise a single-period utility function, V=V(L,CG,CO;H), where CG is the

time the adult spends caring for an elderly parent; CO is outside care, which is

either purchased in the market or provided by other family members; and the

term H indexes the need for care of the elderly.

Data on the time allocated to caregiving are largely missing from our dataset. In the Indonesian context, where aged care is generally provided by household members and is rarely purchased, we can reasonably assume that all care is pro-vided by household members. Therefore, we proxy the cost of CO using a set of

householdspeciic variables, such as the number of workingage adults in the

household, the number of children aged 0–14, the number of adult siblings not residing with the parents, and whether the house is self-owned.

Econometric speciication

We estimate the impact of parental health on the migration decision of individual i during time t using a reduced-form binary choice model:

α β β ε

= + + + +

migi CGˆi Zi 1 Xi 2 Cj i (1)

where migi is a binary variable equal to one if individual i participates in the

migrant market; CGˆi refers to the probability that individual i has an elderly

par-ent living in close proximity who is in poor health; Zi and Xi are vectors of house-hold and individual characteristics that affect individual i’s ability or desire to

5 There is considerable public debate in Indonesia about the numbers, rights and protec -tion of women who leave the country to work abroad (Silvey 2006). Discussion of these issues is beyond the scope of the current study, however.

participate in the migrant market; and Cj captures community characteristics such as the province of residence of the individual.

The X vector includes characteristics such as the adult child’s age, gender,

edu-cational attainment and marital status. These could be expected to inluence the

attractiveness of migration through their effect on the potential wage premium an individual might be able to earn as a migrant compared with local employment, and through their effect on the individual’s preference for participation in the migrant market.

The caregiving variable, CGˆ, is hard to measure because there is no question in the IFLS that allows us to identify a caregiver. The ideal dependent variable for

the irst equation, time allocated to care of an elderly parent, is not observed. We

do know, however, whether adult children are residing near or with their parents, so that we can estimate the conditional probability of the event that ‘a working-age adult is living in proximity to an elderly parent who is in poor health’. Taking this conditional probability as being equal to the expectation of the event, we

deine a respondent as being a caregiver if two conditions are met simultaneously:

the respondent has an elderly parent aged 60 years or above living in the same province ((HH60+) = 1); and the elderly parent reports being in poor health.

Since we cannot actually observe caregiving by adult children, our caregiving

variable implicitly deines a population ‘at risk’ of being a caregiver. Assuming

that both elderly Indonesians and their children prefer to live independently if

they are able to do so, we further adopt a broad deinition of caregiving, where

the adult child lives in close proximity to the elderly parents rather than actually

residing with them. Kreager and SchröderButterill (2008: 51–2) also ind that

elderly Indonesians prefer to live on their own or with one reliable child living

close by. However, as a robustness test, we explore a more restricted deinition

where the adult child lives with the elderly parents.

A priori, it is dificult to predict the effect of an elderly parent’s ill health on a

working-age child’s decision to migrate. On the one hand, the scarcity of pensions and aged-care services might make participation in the migrant market less attrac-tive if the individual has an elderly parent who is not in good health – especially if there are no siblings to act as alternative caregivers. But on the other hand, it is possible that the presence of an elderly parent who is in poor health might actu-ally increase the likelihood of a working-age adult migrating, to ease the strain

placed on the family inances by the parent’s illness.

The two main econometric issues that we face in this framework are the poten-tial endogeneity of the caregiving decision, and the question of the robustness of the variables for elderly poor health. We discuss each of these below.

Endogeneity of the caregiving decision

In estimating the impact of caregiving on the propensity to migrate, we need to consider the possible endogeneity of the caregiving decision, because migrants can differ fundamentally from non-migrants. The decision to act as a caregiver for an elderly parent is likely to be endogenous if individuals with a low oppor-tunity cost of time are more likely to provide care for the elderly. Unobservable factors potentially correlated with observations of parental health and migra-tion decisions are a concern, and using pre-determined household characteristics alone will not solve this problem. Several sources of bias may be present. First,

the ability to observe participation in the migrant market may relect a potentially

endogenous decision for the household. For example, the presence of an elderly parent living nearby may facilitate an adult child’s participation in the migrant market if the parent provides some form of informal child care. Alternatively, the adult child may be living close to the parents because he or she lacks the initiative

or networks required to migrate. Finally, caring for an elderly parent may relect

the outcome of a bargaining process among siblings, with the individual who chooses to care for the parents making an implicit decision not to participate in the migrant market. In this case, caring for an elderly parent would be related to participation in the migrant market.

We include three instruments to address the potential endogeneity of the care-giving decision, based on traditional community-level expectations about the care of the elderly. The 2007–08 IFLS contained a unique questionnaire in which community leaders were asked about the traditional laws and customs (adat)

pertaining to the living arrangements of the elderly. The responses relect long

standing cultural practices, and we therefore assume that these are distinct from current labour market signals. We believe that these social norms provide us with a completely exogenous measure of community-level expectations about elderly

caregiving and coresidence with adult children. These norms will inluence the

likelihood of a respondent being a caregiver, but are not directly related to the respondent’s decision to migrate.

The speciic communitynorm variables that we include as instruments for the

endogeneity of caregiving are whether there is an expectation for children to take

care of elderly parents; whether the caregiving child receives a higher share of the inheritance; and whether the caregiving child inherits the family home. The migration participation equation is identiied by the exclusion of variables relat -ing to community social norms.

Robustness of health measures

The next issue to consider is the robustness of our health measures. We deine

the elderly as those persons aged 60 years or over in 2000. The dataset provides

several alternative measures of selfreported health for respondents aged 50 years and above. We focus irst on the selfassessed measures of poor health available

in the 2000 dataset for all elderly persons. The questionnaire asked respondents whether they had suffered from a serious illness in the last four years, and to rate their health on a simple scale. We describe an elderly parent as being in poor health if they said they had suffered from a serious illness in the last four years and, in addition, described themselves on the scale as being either ‘unhealthy’ or ‘somewhat unhealthy’.

We are aware of several concerns about the use of self-assessed health measures. In particular, Lindeboom and Van Doorslaer (2004: 1,084) raise the possibility that individuals with the same level of ‘true’ health may rate their health quite differ-ently, because of differences in the way sub-groups interpret thresholds and cat-egories when asked to rate their health on a simple scale.6 This could potentially

6 For example, individuals may report improved health if some time has elapsed since the diagnosis of a serious condition. Also, individuals may rate themselves in comparison with others in the same cultural group, peer group, educational bracket or income level, leading to selfassessments that differ greatly from more objective measures of ‘true’ health.

make the interpretation of self-assessed health status problematic. An additional problem is that some individuals exhibit considerable uncertainty about their self-assessed health status, increasing the likelihood of measurement error (Crossley and Kennedy 2000: 9). Despite these concerns, self-assessed health measures are

typically interpreted as objective measures of health, and are commonly used in

empirical research from both developed and developing countries.7

To test the robustness of our self-assessed health measure, ideally we would

like to use objective measures of poor health for the entire sample of elderly per -sons. Our dataset allows us to construct two such measures, but only for the sam-ple of elderly parents who are residing with an adult child. These measures are the elderly parent’s body mass index (BMI) and the parent’s ability to undertake activities of daily living (ADL).

To measure BMI, we use the height and weight measures available in the 2000 dataset, using the standard formula:

=

BMI weight kg height m

( ) ( )

2 2

A BMI below 18.5 suggests that the person is underweight, which would increase their susceptibility to illness. Therefore, the dummy variable takes a value of one

if the elderly person has a BMI below 18.5.

Household members were also asked a series of questions about their ability

to perform 10 common daily activities: carry a heavy load for 20 metres; walk for 5 kilometres; walk for 1 kilometre; bend over, squat and kneel; sweep the loor or yard; draw a pail of water from a well; stand up from sitting on the loor without help; stand up from sitting in a chair without help; dress without help; and go to

the bathroom without help. We use this information to construct a dummy

vari-able for ADL that takes a value of one if the elderly person has dificulty carrying out at least ive of the 10 activities, or is unable to do so.

In addition to BMI and ADL, we include a variable representing a negative health shock as another test of the robustness of the self-assessed health measure. This variable takes a value of one if there has been a deterioration in the self-assessed health status of the elderly parent between 2000 and 2007, that is, if the parent reported being in good health in 2000 but in poor health in 2007.

We test the robustness of the self-assessed health measure by estimating the models separately for the three alternative measures of elderly poor health. In addition, we estimate a model where the caregiver lives with – rather than near – an elderly parent whose health is self-assessed as poor. Summing up, our

care-giving variable covers the following ive situations, each of which is modelled

separately.

• Speciication 1: adult child lives in the same province as an elderly parent, and

the parent is in poor health as measured by self-assessment.

• Speciication 2: adult child lives with an elderly parent, and the parent is in

poor health as measured by self-assessment.

7 Examples include Deaton and Paxson (1998) and Kennedy et al. (1998) for developed countries, and Frankenberg and Jones (2004), Idler and Benyamini (1997) and Jylha (2009) for developing countries.

• Speciication 3: adult child lives with an elderly parent, and the parent is in

poor health as measured by BMI.

• Speciication 4: adult child lives with an elderly parent, and the parent is in

poor health as measured by ADL.

• Speciication 5: adult child lives with an elderly parent, and the parent is in

poor health as measured by a negative health shock between 2000 and 2007.

DATA

The data used in this paper come from the 2000 and 2007–08 rounds of the IFLS. These rich and unique datasets contain detailed information on households’ demographic, labour market and economic characteristics, consumption and health expenditures, and access to health care facilities and social safety nets. It is ideal for our study because it provides detailed information on migrant moves, migrant destinations and the reasons for migration.

The household is our unit of analysis, and our sample consists of individuals

who were of working age in 2000, that is, those aged 20–59 years. We restrict the

analysis to those individuals for whom we have data on all variables of interest

in both 2000 and 2007. There are 7,359 such individuals in the sample. We model

the migration decisions of working-age adults with potential caregiving responsi-bilities for elderly parents. We assume that the propensity to migrate will depend on whether or not an adult is an informal caregiver to an elderly parent who is in poor health.

The main dependent variable in the analysis is a binary variable indicating the migration status of a working-age household member. Using data on migration in

the 2007–08 IFLS, we deine a migrant as an individual aged 20–59 years in 2000

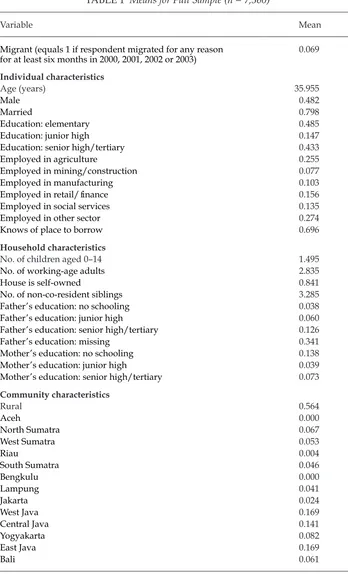

who migrated for a period of at least six months in 2000, 2001, 2002 or 2003 for any purpose. We impose this time restriction because we are interested in whether ill health among the elderly at the time of the survey affected the propensity of the respondent to migrate. Table 1 describes the variables used in the analysis for the full sample. It shows that approximately 6.9% of respondents in the sample are migrants.

The decision to migrate is likely to depend on a wide array of individual, house-hold and labour market characteristics, as well as the health of older househouse-hold members. A key explanatory variable in our analysis is the caregiving variable.

As indicated previously, in addition to the model for children living near an

elderly parent who is in poor health (speciication 1), as a robustness check we

present estimates for models where the sample is restricted to working-age adults living with the elderly parent (speciications 2–5). The proportion of respondents who are potential caregivers differs depending on the measure of poor health used (table 1). While 20.9% of working-age adults live in the same province as

an elderly parent whose selfreported health is poor (speciication 1), only 10.3% actually reside with the elderly parent (speciication 2). Another 11.6% of respond

-ents live with a parent whose health is poor as indicated by a low BMI (speciica

-tion 3), but just 4.4% with a parent who is unable to perform at least ive of the 10 activities of daily living (speciication 4). The proportion living with a parent who has experienced a negative health shock, meanwhile, is 8.4% (speciication 5). Of

course, it is possible that the adult child does not contribute to the elderly parent’s

TABLE 1 Means for Full Sample (n = 7,360)

Variable Mean

Migrant (equals 1 if respondent migrated for any reason for at least six months in 2000, 2001, 2002 or 2003)

0.069

Individual characteristics

Age (years) 35.955

Male 0.482

Married 0.798

Education: elementary 0.485

Education: junior high 0.147

Education: senior high/tertiary 0.433

Employed in agriculture 0.255

Employed in mining/construction 0.077

Employed in manufacturing 0.103

Employed in retail/inance 0.156

Employed in social services 0.135

Employed in other sector 0.274

Knows of place to borrow 0.696

Household characteristics

No. of children aged 0–14 1.495

No. of working-age adults 2.835

House is self-owned 0.841

No. of non-co-resident siblings 3.285

Father’s education: no schooling 0.038

Father’s education: junior high 0.060

Father’s education: senior high/tertiary 0.126

Father’s education: missing 0.341

Mother’s education: no schooling 0.138

Mother’s education: junior high 0.039

Mother’s education: senior high/tertiary 0.073

Community characteristics

Rural 0.564

Aceh 0.000

North Sumatra 0.067

West Sumatra 0.053

Riau 0.004

South Sumatra 0.046

Bengkulu 0.000

Lampung 0.041

Jakarta 0.024

West Java 0.169

Central Java 0.141

Yogyakarta 0.082

East Java 0.169

Bali 0.061

care. However, given the lack of data on time allocated to caring for an elderly parent, we are unable to use a more precise measure of elderly caregiving.

We include in our models several characteristics intended to pick up differences between individuals who do and do not migrate. Two of the key determinants of

the decision to migrate are the expected likelihood of inding employment and

the expected wage differential should the individual choose to migrate. Both are likely to depend on the human capital of the migrant, since individuals with

higher levels of human capital are more likely to be able to ind employment and

to earn higher wages if they choose to migrate.

Human capital is captured by variables such as the educational level and sec-tor of employment of the respondent. Educational attainment is the highest level

of schooling a respondent has completed, namely elementary, junior high, and

senior high or higher (with no education being the reference category). These cat-egories correspond to six, nine, and 12 or more years of schooling respectively.

Respondents with tertiary qualiications are pooled with senior high school grad -uates because there are so few of them in the sample. Table 1 indicates that 43.3% of respondents fall into this category.

TABLE 1 (continued) Means for Full Sample (n = 7,360)

Variable Mean

Community characteristics (continued)

West Nusa Tenggara 0.056

Central Kalimantan 0.000

South Kalimantan 0.037

East Kalimantan 0.000

South Sulawesi 0.050

Central Sulawesi 0.000

Parent’s residence and health status Speciication 1: respondent lives in same province as elderly parent, and parent is in poor health as measured by self-assessment

0.209

Speciication 2: respondent lives with elderly parent, and parent is in poor health as measured by self-assessment

0.103

Speciication 3: respondent lives with elderly parent, and parent is in poor health as measured by body mass index (BMI)

0.116

Speciication 4: respondent lives with elderly parent, and parent is in poor health as measured by activities of daily living (ADL)

0.044

Speciication 5: respondent lives with elderly parent, and parent is in poor health as measured by a negative health shock between 2000 and 2007

0.084

Instruments

Social norm: elderly person lives with adult child 0.443

Social norm: caregiving child inherits more 0.329 Social norm: caregiving child inherits house 0.426

To capture information on respondents’ sectors of employment, we construct indicator variables for employment in agriculture, mining/construction,

manu-facturing, retail/inance, social services and ‘other’ sectors (with unemployment

as the base category).

The variables capturing a household’s economic status are whether the house is self-owned and whether the respondent knows of a place to borrow money should this be necessary. We also include a set of household-level demographic and individual controls, including the number of working-age adults in the household, the number of children aged 0–14 years, and the age, gender and

mar-ital status of the respondent, to control for lifecycle effects that may inluence

the decision to participate in the migrant market. Finally, we include an indicator variable for whether the respondent has siblings living in the same province who do not reside with the parents (non-co-resident siblings), to provide an indication of alternative sources of care should an elderly parent fall ill. According to table 1,

the average household has 1.5 children aged 0–14, and the average respondent

has 3.3 adult siblings living in close proximity to an elderly parent whose health is self-assessed as poor.

RESULTS

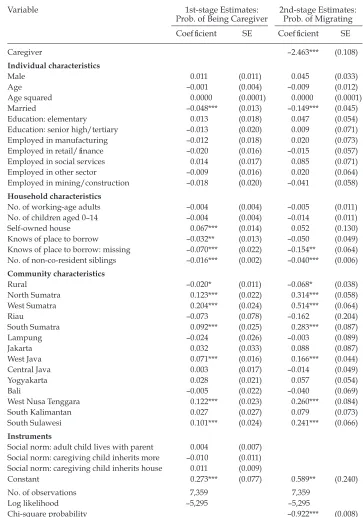

The main results of the analysis are presented in tables 2–6. Based on an instrumen-tal variable (IV) probit estimation, table 2 presents the results for the propensity to

migrate for the full sample. In this speciication we do not include any informa

-tion on parental educa-tion. A caregiver is deined here broadly as an adult child

who lives in close proximity to an elderly parent whose health is self-assessed as

poor (speciication 1). The two dependent variables are a dummy for the prob -ability of being a caregiver and a dummy for the prob-ability of migration. For

the full sample, we ind that caregiving responsibility for an elderly parent has a statistically signiicant and negative association with the propensity to migrate.

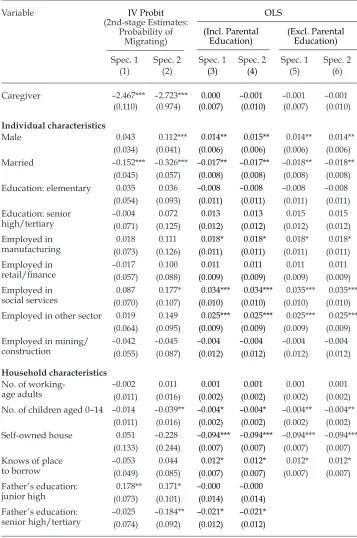

Table 3 presents estimates for both the broad and narrow deinitions of care giving, that is, where the caregiver lives near (speciication 1) or with (specii -cation 2) a parent whose health is self-assessed as poor. This time, we include

information on parental education. In the IV probit estimations, we ind a sta

-tistically signiicant and negative correlation between caregiving responsibilities and the migration decisions of workingage adults, for both speciications. No statistically signiicant relationship is observed for the caregiving variable in the

ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates, however, regardless of whether or not information on parental information is included.

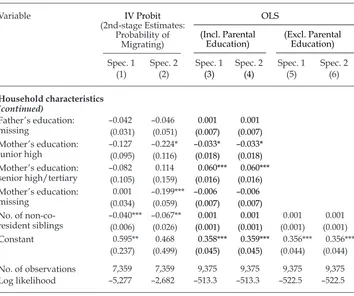

Table 4 illustrates the differential impact of caregiving on the probability of migration for the male and female samples. The results presented in columns 1–4

illustrate that while caregiving responsibilities signiicantly reduce the probabil

-ity of migration for females (for both speciications 1 and 2), for males there is a positive association between caregiving and migration in both speciications.

How robust are the indings to changes in the deinition of poor health and

in the gender of the recipient of care? To test the robustness of the results for the full sample, we use alternative measures of elderly poor health in the caregiving measure used in the IV probit strategies, distinguishing between male and female elderly parents.

TABLE 2 Instrumental Variable Estimation of Relationship between Caregiving and Probability of Migrating, Excluding Information on Parental Education, Speciication 1a

Variable 1st-stage Estimates:

Prob. of Being Caregiver 2nd-stage Estimates: Prob. of Migrating Coeficient SE Coeficient SE

Caregiver –2.463*** (0.108)

Individual characteristics

Male 0.011 (0.011) 0.045 (0.033)

Age –0.001 (0.004) –0.009 (0.012)

Age squared 0.0000 (0.0001) 0.0000 (0.0001)

Married –0.048*** (0.013) –0.149*** (0.045)

Education: elementary 0.013 (0.018) 0.047 (0.054)

Education: senior high/tertiary –0.013 (0.020) 0.009 (0.071)

Employed in manufacturing –0.012 (0.018) 0.020 (0.073)

Employed in retail/inance –0.020 (0.016) –0.015 (0.057)

Employed in social services 0.014 (0.017) 0.085 (0.071)

Employed in other sector –0.009 (0.016) 0.020 (0.064)

Employed in mining/construction –0.018 (0.020) –0.041 (0.058)

Household characteristics

No. of working-age adults –0.004 (0.004) –0.005 (0.011)

No. of children aged 0–14 –0.004 (0.004) –0.014 (0.011)

Self-owned house 0.067*** (0.014) 0.052 (0.130)

Knows of place to borrow –0.032** (0.013) –0.050 (0.049)

Knows of place to borrow: missing –0.070*** (0.022) –0.154** (0.064) No. of non-co-resident siblings –0.016*** (0.002) –0.040*** (0.006)

Community characteristics

Rural –0.020* (0.011) –0.068* (0.038)

North Sumatra 0.123*** (0.022) 0.314*** (0.058)

West Sumatra 0.204*** (0.024) 0.514*** (0.064)

Riau –0.073 (0.078) –0.162 (0.204)

South Sumatra 0.092*** (0.025) 0.283*** (0.087)

Lampung –0.024 (0.026) –0.003 (0.089)

Jakarta 0.032 (0.033) 0.088 (0.087)

West Java 0.071*** (0.016) 0.166*** (0.044)

Central Java 0.003 (0.017) –0.014 (0.049)

Yogyakarta 0.028 (0.021) 0.057 (0.054)

Bali –0.005 (0.022) –0.040 (0.069)

West Nusa Tenggara 0.122*** (0.023) 0.260*** (0.084)

South Kalimantan 0.027 (0.027) 0.079 (0.073)

South Sulawesi 0.101*** (0.024) 0.241*** (0.066)

Instruments

Social norm: adult child lives with parent 0.004 (0.007) Social norm: caregiving child inherits more –0.010 (0.011) Social norm: caregiving child inherits house 0.011 (0.009)

Constant 0.273*** (0.077) 0.589** (0.240)

No. of observations 7,359 7,359

Log likelihood –5,295 –5,295

Chi-square probability –0.922*** (0.008)

a SE = standard error. *** = signiicant at 1%; ** = signiicant at 5%; * = signiicant at 10%. Dependent

variable = 1 if the respondent migrated in 2000, 2001, 2002 or 2003. Speciication 1: respondent lives in same province as elderly parent, and parent is in poor health as measured by self-assessment.

TABLE 3 Instrumental Variable (IV) and Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Estimations of Relationship between Caregiving and Probability of Migrating,

Including Information on Parental Education, Speciications 1 and 2a

Variable IV Probit

Caregiver –2.467*** –2.723*** 0.000 –0.001 –0.001 –0.001

(0.110) (0.974) (0.007) (0.010) (0.007) (0.010)

Individual characteristics

Male 0.043 0.112*** 0.014** 0.015** 0.014** 0.014**

(0.034) (0.041) (0.006) (0.006) (0.006) (0.006)

Married –0.152*** –0.326*** –0.017** –0.017** –0.018** –0.018**

(0.045) (0.057) (0.008) (0.008) (0.008) (0.008)

Education: elementary 0.035 0.036 –0.008 –0.008 –0.008 –0.008

(0.054) (0.093) (0.011) (0.011) (0.011) (0.011) Education: senior

high/tertiary

–0.004 0.072 0.013 0.013 0.015 0.015

(0.071) (0.125) (0.012) (0.012) (0.012) (0.012) Employed in

manufacturing

0.018 0.111 0.018* 0.018* 0.018* 0.018*

(0.073) (0.126) (0.011) (0.011) (0.011) (0.011) Employed in

retail/inance –0.017(0.057) (0.088)0.100 (0.009)0.011 (0.009)0.011 (0.009)0.011 (0.009)0.011 Employed in

social services

0.087 0.177* 0.034*** 0.034*** 0.035*** 0.035*** (0.070) (0.107) (0.010) (0.010) (0.010) (0.010) Employed in other sector 0.019 0.149 0.025*** 0.025*** 0.025*** 0.025***

(0.064) (0.095) (0.009) (0.009) (0.009) (0.009) Employed in mining/

construction

–0.042 –0.045 –0.004 –0.004 –0.004 –0.004

(0.055) (0.087) (0.012) (0.012) (0.012) (0.012)

Household characteristics No. of

working-age adults

–0.002 0.011 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001

(0.011) (0.016) (0.002) (0.002) (0.002) (0.002) No. of children aged 0–14 –0.014 –0.039** –0.004* –0.004* –0.004** –0.004**

(0.011) (0.016) (0.002) (0.002) (0.002) (0.002) Self-owned house 0.051 –0.228 –0.094*** –0.094*** –0.094*** –0.094***

(0.133) (0.244) (0.007) (0.007) (0.007) (0.007) Knows of place

to borrow

–0.053 0.044 0.012* 0.012* 0.012* 0.012* (0.049) (0.085) (0.007) (0.007) (0.007) (0.007) Father’s education:

junior high (0.073)0.178** (0.101)0.171* –0.000(0.014) –0.000(0.014) Father’s education:

senior high/tertiary

–0.025 –0.184** –0.021* –0.021* (0.074) (0.092) (0.012) (0.012)

Gender differences in the propensity to migrate

An important question is whether sons or daughters are more likely to support their elderly parents. Frankenberg and Kuhn (2004: 11–13, 27) argue that Indo nesia (or at least Java) has a relatively egalitarian society in which sons and daughters are equally likely to support their parents. However, their study is based on remit-tances sent home by migrant children, not physical care provided by children who live near or with elderly parents.

Our results show that being male is signiicantly and positively associated with the probability of migration, when a caregiver is deined as an adult child liv -ing with an elderly parent who is in poor health as measured by self-assessment (table 3, column 2). Similarly, in the gender-disaggregated IV probit models

pre-sented in table 4, for both speciications 1 and 2 (adult children living respectively

near and with an elderly parent in self-assessed poor health), there is a

statisti-cally signiicant and positive association between the caregiver variable and the

TABLE 3 (continued) Instrumental Variable (IV) and Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Estimations of Relationship between Caregiving and Probability of Migrating, Including Information on Parental Education, Speciications 1 and 2a

Variable IV Probit

junior high –0.127(0.095) –0.224*(0.116) –0.033*(0.018) –0.033*(0.018)

Mother’s education:

–0.040*** –0.067** 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001 (0.006) (0.026) (0.001) (0.001) (0.001) (0.001)

Constant 0.595** 0.468 0.358*** 0.359*** 0.356*** 0.356***

(0.237) (0.499) (0.045) (0.045) (0.044) (0.044)

No. of observations 7,359 7,359 9,375 9,375 9,375 9,375

Log likelihood –5,277 –2,682 –513.3 –513.3 –522.5 –522.5

a *** = signiicant at 1%; ** = signiicant at 5%; * = signiicant at 10%. Standard errors are in brackets.

Dependent variable = 1 if the respondent migrated in 2000, 2001, 2002 or 2003. Provincial dummy vari -ables are included in all models. Speciication 1: respondent lives in same province as elderly parent, and parent is in poor health as measured by selfassessment. Speciication 2: respondent lives with elderly parent, and parent is in poor health as measured by self-assessment.

414

Anu Rammohan and Elisabetta Magnani

TABLE 4 Instrumental Variable (IV) and Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Estimations of Relationship between

Caregiving and Probability of Migrating, by Gender of Respondent, Speciications 1 and 2a

Variable IV Probit

(2nd–stage Estimates: Probability of Migrating) OLS

Speciication 1 Speciication 2 Speciication 1 Speciication 2

Male Sample

Female Sample

Male Sample

Female Sample

Male Sample

Female

Sample

Male Sample

Female

Sample

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8)

Caregiver 2.516*** –2.366*** 3.470*** –3.340*** –0.004 0.004 0.008 –0.011

(0.046) (0.172) (0.153) (0.320) (0.010) (0.009) (0.014) (0.013)

Individual characteristics

Married 0.098* –0.224*** 0.275*** –0.404*** –0.008 –0.023** –0.007 –0.024**

(0.056) (0.070) (0.059) (0.064) (0.013) (0.010) (0.013) (0.010)

Education: elementary –0.071 0.045 –0.007 0.036 –0.014 –0.005 –0.015 –0.005

(0.081) (0.083) (0.086) (0.095) (0.020) (0.013) (0.020) (0.013)

Education: senior high/tertiary –0.018 0.038 0.061 0.080 –0.001 0.024 –0.001 0.024

(0.087) (0.107) (0.093) (0.117) (0.021) (0.015) (0.021) (0.015)

Employed in manufacturing 0.116 0.114 0.205* 0.125 0.030* 0.008 0.030* 0.008

(0.091) (0.090) (0.110) (0.098) (0.016) (0.015) (0.016) (0.015)

Employed in retail/inance 0.051 –0.049 0.099 0.013 0.036** –0.007 0.036** –0.007

(0.101) (0.070) (0.130) (0.078) (0.015) (0.012) (0.015) (0.012)

Employed in social services –0.017 0.123 0.027 0.102 0.051*** 0.015 0.051*** 0.015

(0.084) (0.090) (0.108) (0.099) (0.014) (0.014) (0.014) (0.014)

Employed in other sectors 0.097 0.063 0.114 0.124 0.035 0.016 0.035 0.016

(0.101) (0.075) (0.109) (0.080) (0.021) (0.011) (0.021) (0.011)

Employed in mining/construction 0.042 –0.209 0.092 –0.121 0.002 0.063 0.003 0.063

Modelling the inluence of caring for the elderly on migration

415

Household characteristics

No. of working-age adults –0.008 –0.012 –0.003 –0.003 0.000 0.001 0.000 0.001

(0.014) (0.016) (0.015) (0.017) (0.003) (0.003) (0.003) (0.003)

No. of children aged 0–14 0.011 –0.006 0.028 –0.028 –0.006* –0.002 –0.006* –0.003

(0.016) (0.016) (0.019) (0.018) (0.003) (0.003) (0.003) (0.003)

Self-owned house –0.179 –0.052 –0.278* –0.124 –0.093*** –0.094*** –0.093*** –0.093***

(0.120) (0.138) (0.161) (0.144) (0.011) (0.010) (0.011) (0.010)

Knows of place to borrow 0.100* –0.014 0.102 0.019 0.010 0.015 0.011 0.014

(0.059) (0.062) (0.067) (0.067) (0.012) (0.009) (0.012) (0.009)

Father’s education: junior high –0.256** 0.062 –0.194* 0.102 0.018 –0.017 0.017 –0.016

(0.105) (0.114) (0.113) (0.122) (0.022) (0.019) (0.022) (0.019)

Father’s education: senior high/ tertiary

–0.016 –0.072 –0.009 –0.236** –0.025 –0.020 –0.025 –0.020

(0.096) (0.103) (0.106) (0.106) (0.019) (0.016) (0.019) (0.016)

Father’s education: missing 0.030 –0.021 0.069 –0.017 –0.010 0.011 –0.010 0.011

(0.046) (0.052) (0.052) (0.058) (0.010) (0.009) (0.010) (0.009) Mother’s education: junior high –0.004 –0.185 0.021 –0.284* –0.046* –0.016 –0.045* –0.017

(0.140) (0.137) (0.153) (0.146) (0.027) (0.024) (0.027) (0.024)

Mother’s education: senior high/ tertiary

0.207 0.016 0.207 0.111 0.070*** 0.051** 0.071*** 0.050** (0.132) (0.132) (0.149) (0.138) (0.024) (0.022) (0.024) (0.022)

Mother’s education: missing –0.032 –0.025 0.152*** –0.258*** 0.004 –0.013 0.004 –0.014

(0.044) (0.050) (0.050) (0.055) (0.010) (0.009) (0.010) (0.009)

No. of non-co-resident siblings 0.048*** –0.035*** 0.091*** –0.081*** 0.002 0.001 0.002 0.001

(0.008) (0.009) (0.009) (0.012) (0.002) (0.002) (0.002) (0.002)

Constant –1.026*** 0.265 –1.473*** 0.371 0.389*** 0.356*** 0.384*** 0.358***

(0.295) (0.326) (0.304) (0.363) (0.070) (0.058) (0.070) (0.058)

No. of observations 3,549 3,810 3,549 3,810 4,555 4,820 4,555 4,820

Log likelihood –2,609 –2,626 –1,445 –1,181 –454.80 –16.09 –454.80 –15.86

a *** = signiicant at 1%; ** = signiicant at 5%; * = signiicant at 10%. Standard errors are in brackets. Dependent variable = 1 if the individual migrated in 2000, 2001, 2002 or 2003. Respondent’s age and age squared, and provincial dummy variables, are included in all models. Speciication 1: respondent lives in same province as elderly parent, and parent is in poor health as measured by selfassessment. Speciication 2: respondent lives with elderly parent, and parent is in poor health

migration decision for the male sample, but a statistically signiicant and negative one for the female sample. This is consistent with the inding of Van Eeuwijk (2006: 69) and SchröderButterill (2005: 8) that care of the elderly is typically the

responsibility of the female members of the household in Indonesia.

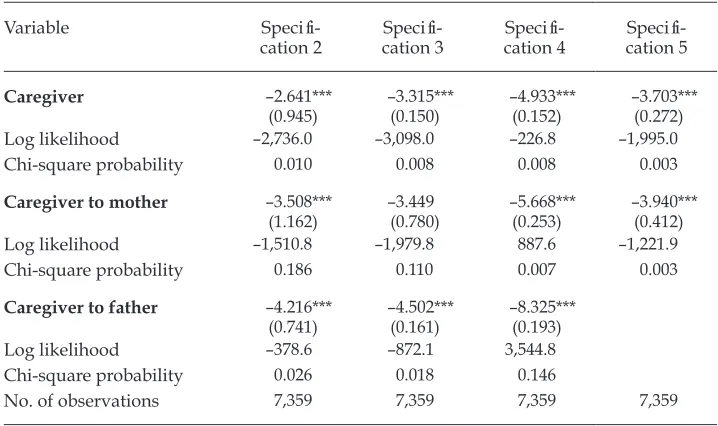

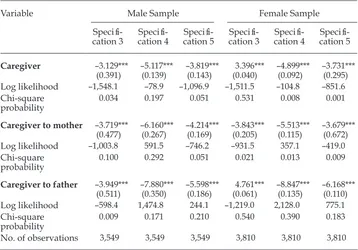

A less researched aspect is whether the gender of the parent inluences the pro -pensity to migrate. To address this issue, we present key results for the full sample

(table 5), and for the disaggregated male and female samples (table 6), depending

on whether the recipient of care is the mother or father of the respondent. For

the full sample shown in table 5, there is a statistically signiicant and negative

association between the probability of migration and caregiving responsibilities, regardless of whether the recipient of care is the mother or the father. This is the case for all four measures of elderly poor health. In table 6, however, we observe a

positive and statistically signiicant sign for the female sample when the recipient of care is the father and poor health is measured using BMI (speciication 3). In

the case of males, the sign for the caregiving variable is always negatively signed, regardless of the health measure used.

In general, though, the coeficient of the caregiving variable is statistically sig

-niicant and negatively signed, regardless of the gender of either the caregiver or

the recipient of care.

TABLE 5 Instrumental Variable Estimation of Relationship between Caregiving and Probability of Migrating, Speciications 2–5a

Variable Specii

(0.945) –3.315***(0.150) –4.933***(0.152) –3.703***(0.272)

Log likelihood –2,736.0 –3,098.0 –226.8 –1,995.0

Chi-square probability 0.010 0.008 0.008 0.003

Caregiver to mother –3.508***

Log likelihood –1,510.8 –1,979.8 887.6 –1,221.9

Chi-square probability 0.186 0.110 0.007 0.003

Caregiver to father –4.216***

No. of observations 7,359 7,359 7,359 7,359

a *** = signiicant at 1%; ** = signiicant at 5%; * = signiicant at 10%. Standard errors are in brackets.

Estimates include controls for individual, household and community characteristics. Dependent vari-able = 1 if the respondent migrated in 2000, 2001, 2002 or 2003. Speciication 2: respondent lives with elderly parent, and parent is in poor health as measured by selfassessment. Speciication 3: respond -ent lives with elderly par-ent, and par-ent is in poor health as measured by body mass index (BMI). Speciication 4: respondent lives with elderly parent, and parent is in poor health as measured by activities of daily living (ADL). Speciication 5: respondent lives with elderly parent, and parent is in poor health as measured by negative health shock between 2000 and 2007.

Inluence of other variables

We turn now to the role of other variables, focusing on speciications 1 and 2 (table 3). While the number of workingage adults in the household is insignii

-cant in inluencing migration decisions, it is noteworthy that when a caregiver is deined as an adult living with the elderly person (speciication 2), there is a

negative correlation between migration and the presence of children aged 0–14 years. The negative sign for the variable for non-co-resident siblings indicates that an increase in the number of siblings living in close proximity to an elderly par-ent whose health is self-assessed as poor reduces the probability of the respond-ent migrating. One explanation for this counter-intuitive result may be that the respondent is the primary caregiver for the elderly parents.

In terms of the inluence of individual characteristics, we note that a respond

-ent’s educational level does not signiicantly affect the propensity to migrate, but

that being married reduces the likelihood of migration (table 3). Although not

shown in table 3, for all models, we ind that residents of Sumatra (North, South and West), South Sulawesi, West Nusa Tenggara and West Java are signiicantly

more likely to migrate than respondents from the reference category, East Java. TABLE 6 Instrumental Variable Estimation of Relationship between Caregiving

and Probability of Migrating, by Gender of Respondent, Speciications 3–5a

Variable Male Sample Female Sample

Specii

cation 3 cation 4Specii cation 5Specii cation 3Specii cation 4Specii cation 5Specii

Caregiver –3.129***

Log likelihood –1,548.1 –78.9 –1,096.9 –1,511.5 –104.8 –851.6

Chi-square probability

0.034 0.197 0.051 0.531 0.008 0.001

Caregiver to mother –3.719***

Log likelihood –1,003.8 591.5 –746.2 –931.5 357.1 –419.0

Chi-square probability

0.100 0.292 0.051 0.021 0.013 0.009

Caregiver to father –3.949***

Log likelihood –598.4 1,474.8 244.1 –1,219.0 2,128.0 775.1

Chi-square probability

0.009 0.171 0.210 0.540 0.390 0.183

No. of observations 3,549 3,549 3,549 3,810 3,810 3,810

a *** = signiicant at 1%; ** = signiicant at 5%; * = signiicant at 10%. Standard errors are in brackets.

Estimates include controls for individual, household and community characteristics. Dependent vari-able = 1 if the respondent migrated in 2000, 2001, 2002 or 2003. Speciication 3: respondent lives with elderly parent, and parent is in poor health as measured by body mass index (BMI). Speciication 4: respondent lives with elderly parent, and parent is in poor health as measured by activities of daily living (ADL). Speciication 5: respondent lives with elderly parent, and parent is in poor health as measured by a negative health shock between 2000 and 2007.

CONCLUSIONS

Migration in search of better employment prospects is widely regarded as an important means of mitigating the adverse consequences of poverty, particularly in rural areas. However, in an environment where social safety nets for the elderly are scarce, looking after elderly parents is generally the responsibility of adult

children. Under these circumstances, even if there are economic beneits from

migration, the need to care for elderly parents is likely to affect an individual’s propensity to migrate.

In this paper, using data from the IFLS, we have examined the manner in which the responsibility to care for an elderly parent who is in poor health affects the migration decisions of working-age adults. Our results indicate that there is a

statistically signiicant and negative correlation between caregiving responsibili -ties and migration. That is, adult children who are looking after an elderly parent who is in poor health are less likely to migrate, regardless of whether they are

living near or with the parent. These indings are robust across different specii -cations using alternative measures of elderly poor health, both self-assessed and

objective. There are some gender differences in the likelihood of migrating, with male caregivers signiicantly more likely to migrate than female caregivers. From

a policy perspective, our results have implications for the design of policies on pensions and health care for the elderly.

REFERENCES

Agesa, R.U. (2001) ‘Migration and the urban to rural earnings difference: a sample selection approach’, Economic Development and Cultural Change 49 (4): 847–65.

Ariianto, A. (2005) ‘Social security reform in Indonesia: a critical analysis’, Unpublished paper, SMERU Research Institute, Jakarta.

Benjamin, D., Brandt, L. and Giles, J. (2005) ‘The evolution of income inequality in rural China’, Economic Development and Cultural Change 53 (4): 769–824.

Bongaarts, J. and Zimmer, Z. (2001) ‘Living arrangements of older adults in the develop-ing world: an analysis of DHS household surveys’, Policy Research Division Workdevelop-ing Paper No. 148, Population Council, New York NY.

Borjas, G. (1989) ‘Economic theory and international migration’, International Migration Review 23: 457–85.

Cameron, L. (2000) ‘The residency decision of elderly Indonesians: a nested logit analysis’, Demography 37: 17–27.

Cameron, L. and CobbClarke, D. (2008) ‘Do coresidency and inancial transfers from the children reduce the need for elderly parents to work in developing countries?’, Journal of Population Economics 21 (4): 1,007–33.

Chan, A. (1997) ‘An overview of the living arrangements and social support exchanges of older Singaporeans’, Asia-Paciic Population Journal 12 (4): 35–50.

Chen, K.P., Chiang, S.H. and Leung, S.F. (2003) ‘Migration, family and risk diversion’, Journal of Labor Economics 21 (2): 353–80.

Crossley, T.F. and Kennedy, S. (2000) ‘The stability of self-assessed health status’, Social and Economic Dimensions of an Aging Population (SEDAP) Research Paper No. 26, McMaster University, Hamilton ON.

Deaton, A.S. and Paxson, C.H. (1998) ‘Ageing and inequality in income and health’, Ameri-can Economic Review 88: 248–53.

Frankenberg, E. and Jones, N.R. (2004) ‘Self-rated health and mortality: does the relation-ship extend to a low-income setting?’, Journalof Health and Social Behavior 45: 441–52.

Frankenberg, E. and Kuhn, R. (2004) ‘The implications of family systems and economic context for intergenerational transfers in Indonesia and Bangladesh’, CCPR02704, Online Working Paper Series, California Center for Population Research, Los Angeles CA, August.

Giles, J. (2006) ‘Is life more risky in the open? Household risk-coping and the opening of China’s labor markets’, Journal of Development Economics 81 (1): 25–60.

Giles, J. and Mu, R. (2007) ‘Elder parent health and the migration decision of adult children: evidence from rural China’, Demography 44 (2): 265–88.

Giles, J. and Yoo, K. (2007) ‘Precautionary behavior, migrant networks, and household consumption decisions: an empirical analysis using household panel data from rural China’, Review of Economics and Statistics 89 (3): 534–51.

Harris, J.R. and Todaro, M.P. (1970) ‘Migration, unemployment, and development: a two sector analysis’, American Economic Review 60: 126–42.

Hugo, G. (2007) ‘Country proiles: Indonesian labor looks abroad’, Migration Policy Insti -tute, Washington DC, available at <http://www.migrationinformation.org/feature/ display.cfm?ID=594>.

Idler, E.L. and Benyamini, Y. (1997) ‘Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies’, Journal of Health and Social Behavior 38 (1): 21–37.

ILO (International Labour Ofice) (2003) Social Security and Coverage for All: Restructuring the Social Security Scheme in Indonesia: Issues and Options, ILO, Jakarta.

Jylha, M. (2009) ‘What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a uniied conceptual model’, Social Science and Medicine 69: 307–16.

Kennedy, B.P., Kawachi, I., Glass, R. and ProthrowStith, D. (1998) ‘Income distribution, socio-economic status, and self-rated health in the United States: multilevel analysis’, British Medical Journal 317: 917–21.

Kim, I.K. and Choe, E.H. (1992) ‘Support exchange patterns of the elderly in the Republic of Korea’, Asia-Paciic Population Journal 7 (3): 89–104.

Knodel, J., Saengtienchai, C. and Ingersoll-Dayton, B. (1999) ‘Studying the living arrange-ments of the elderly: lessons from a quasi-qualitative case study approach in Thailand’, Journal of Cross-cultural Gerontology 14 (3): 197–220.

Kreager, P. (2006) ‘Migration, social structure and oldage support networks: a comparison of three Indonesian communities’, Ageing and Society 26 (1): 37–60.

Kreager, P. and SchröderButterill, E. (2008) ‘Indonesia against the trend? Ageing and intergenerational wealth lows in two Indonesian communities’, Demographic Research 19 (52): 1,781–810.

Lanzona, L. (1998) ‘Migration, selfselection and earnings in Philippine rural communi -ties’, Journal of Development Economics 56 (1): 27–50.

Leechor, C. (1996) ‘Reforming Indonesia’s pension system’, Policy Research Working Paper No. 1677, World Bank, Washington DC.

Leinbach, T. and Watkins, J.F. (1998) ‘Remittances and circulation behavior in the livelihood process: transmigrant families in South Sumatra’, Economic Geography 74 (1): 45–63. Lindeboom, M. and Van Doorslaer, E. (2004) ‘Cut-point shift and index shift in self-reported

health’, Journal of Health Economics 23 (6): 1,083–99.

Lucas, R. and Stark, O. (1985) ‘Motivations to remit: evidence from Botswana’, Journal of Political Economy 93 (5): 901–18.

Miguel, E., Gertler, P. and Levine, D. (2006) ‘Does industrialization build or destroy social networks?’, Economic Development and Cultural Change 54 (2): 287–317.

Mincer, J. (1978) ‘Family migration decisions’, Journal of Political Economy 86: 749–73. Muhidin, S. (2006) ‘Understanding the impact of migration on the health status of families

leftbehind: indings from the IFLS data’, Unpublished paper, University of Queens -land, Brisbane.

Nas, P.J.M. and Boender, W. (2002) ‘The Indonesian city in urban theory’, in The Indonesian Town Revisited, ed. P.J.M. Nas, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore: 3–17. OECD (Organisation for Co-operation and Development) (2011) ‘Families are changing’,

in Doing Better for Families, OECD, Paris: 17–53, available at <http://www.oecd.org/ social/familiesandchildren/47701118.pdf>.

Rogers, A., Muhidin, S., Jordan, L. and Lea, M. (2004) ‘Indirect estimates of agespeciic interregional migration lows in Indonesia based on the mobility propensities of infants’, Working Paper POP20040001, Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado, Boulder CO.

SchröderButterill, E. (2004) ‘Intergenerational family support provided by older people in Indonesia’, Ageing and Society 24 (4): 497–530.

SchröderButterill, E. (2005) ‘Oldage vulnerability in Indonesia: a longitudinal social net -work approach’, Paper presented to the British Society for Population Studies Confer -ence, University of Kent, Canterbury, 12–14 September.

SchröderButterill, E. and Kreager, P. (2005) ‘Actual and de facto childlessness in old age: evidence and implications from East Java, Indonesia’, Population and Development Review 31 (1): 19–55.

Silvey, R. (2006) ‘Consuming the transnational family: Indonesian migrant domestic work-ers to Saudi Arabia’, Global Networks 6 (1): 23–40.

Stark, O. and Bloom, D.E. (1985) ‘The new economics of labour migration’, American Eco-nomic Review 75: 173–8.

Sumarto, S., Suryahadi, A. and Widyanti, W. (2004) ‘Assessing the impact of Indonesian social safety net programs on household welfare and poverty dynamics’, SMERU Working Paper, SMERU Research Institute, Jakarta, August.

Taylor, J.E., Rozelle, S. and De Brauw, A. (2003) ‘Migration and incomes in source commu-nities: a new economics of migration perspective from China’, Economic Development and Cultural Change 52 (1): 75–101.

UN (United Nations) (2009) ‘World population ageing 2009’, ESA/P/WP/212, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, UN, New York NY, December, available at <http:// www.un.org/esa/population/publications/WPA2009/WPA2009_WorkingPaper. pdf>.

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) (2010) Human Development Report 2010 – 20th Anniversary Edition. The Real Wealth of Nations: Pathways to Human Devel -opment, UNDP, New York NY, available at <http://hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/ hdr2010/>.

Van Eeuwijk, P. (2006) ‘Oldage vulnerability, illhealth and care support in urban areas of Indonesia’, Ageing and Society 26 (1): 61–80.

World Bank (2006) ‘Fact sheet: migration, remittance and female migrant workers’, Female Migrant Workers Research Team, World Bank, Jakarta, January, available at <http:// siteresources.worldbank.org/INTINDONESIA/Resources/fact_sheet migrant_work -ers_en_jan06.pdf>.

Zhao, Y. (2002) ‘Causes and consequences of return migration: recent evidence from China’, Journal of Comparative Economics 30 (2): 376–94.