Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Gender Inequities of Self-Efficacy on Task-Specific

Computer Applications in Business

Joyce Shotick & Paul R. Stephens

To cite this article: Joyce Shotick & Paul R. Stephens (2006) Gender Inequities of Self-Efficacy on Task-Specific Computer Applications in Business, Journal of Education for Business, 81:5, 269-273, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.81.5.269-273

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.81.5.269-273

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 15

View related articles

ABSTRACT. In this article, the authors

investigated the impact of evolving

technol-ogy on gender disparity and the

contradic-tions found in previous research relating to

the computing gender gap to determine if

certain computer software tasks are

gender-specific and if those skills represent a

gen-der gap in technology. Based on the social

cognitive theory and established

methodol-ogy of self-efficacy reporting, the authors

provide an analysis of gender differences in

computing self-efficacy over a variety of

technological skills needed in today’s

busi-ness environment.

Copyright © 2006 Heldref Publications

ot all students are treated equally. Research has shown that some learners have better access to technolo-gy and more opportunities to use soft-ware than others do (Bryson, Petrina, & Braundy, 2003; Messineo & DeOllos, 2005; Volman & van Eck, 2001; Young, 2000). These researchers have also found significant evidence of gender differences in interest, attitudes, access to computers, use of computers, and experiences in the classroom. The gap between males and females, established during adolescence, persists through higher education and beyond. Even within the information technology pro-fession, gender differences exist. Dat-tero and Galup (2004) found that women are more likely than are men to maintain COBOL legacy systems and that men were more likely to engage in Java or C++ language than are women. The authors concluded that women pre-fer using existing systems rather than engineering new ones.

The business workplace has become dependent on computer usage in every aspect of its operations. Firms expect college graduates to have a proficient level of competence and expertise in computer technology (Ferguson, 2000). New hires are assigned projects that require knowledge of a wide variety of software applications. Regardless of gen-der, race, or ethnicity, the business envi-ronment assumes that its new employees

are capable of navigating computer tech-nology (Shotick & Lumpkin, 2001). A persistent gender gap in interest in and knowledge of computer technology cre-ates inefficiency in the workplace, yet it is a problem that is avoidable.

Literature Review

Theories from psychology and soci-ology suggest that gender disparity in computer competence and use exists due to sex role typing (Mira, 1987). If society associates computers with male characteristics, then women will avoid information technology. This could potentially place new female employees at a disadvantage in the workplace. The gender schema theory suggests that sex typing occurs in children as a means of encoding and organizing information about their environments (Bem, 1987). Therefore, supporters of this theory believe that society has created an asso-ciation between computers and “male-ness” (Agosto, 2004). Under this theory, until computer use is required of all stu-dents at a very early age, men will con-tinue to be more attracted to computer use than women, thus creating a gender gap in both experience and knowledge. For the past fifteen years, there has been extensive research on gender differ-ences in computer literacy. The literature seems to appear primarily in information systems, education, and sociology

disci-Gender Inequities of Self-Efficacy on

Task-Specific Computer Applications in

Business

JOYCE SHOTICK PAUL R. STEPHENS BRADLEY UNIVERSITY PEORIA, ILLINOIS

N

plines. The information systems research on gender differences has been focused on the use of the technology (Compeau, Higgins, & Huff, 1999). Education researchers have been concerned with how to minimize the gender gap between differences in computer literacy (Chen, 1986; Sachs & Bellisimo, 1993), where-as the sociology researchers have investi-gated why the differences exist (Harri-son, Rainer, & Hochwarter, 1997; Mira, 1987). All of these aspects of gender dif-ferences in computer literacy are critical to our understanding of how to educate students in the use and development of computer technology.

Recently, Harrison et al. (1997) inves-tigated differences in computer usage by university personnel based on gender. Using both the gender model of work and the job model of work to predict gender differences in computer literacy, they found that men were less fearful of computer technology than women. Thus, educators must first become aware of the gender differences and possible biases that they present in the teaching of computer technology to diminish the gender gap in computer use.

To continue to examine gender differ-ences as well as incorporate the effects of changes in technology, Young (2000) developed a computer attitude survey that included concepts of Internet usage. Relying on previous research (Bunder-son & Christensen, 1995; Koohang, 1989; Newman, Cooper, & Ruble, 1995; Wilder, Mackie, & Cooper, 1985), Young tested gender differences in computer attitudes of middle school and high school students. His findings were consistent with the results of early researchers who found significant gen-der differences in attitudes toward com-puter technology. Male students were more confident in their computer litera-cy than females.

However, because technology has changed and become less dependent on programming skills, Sachs and Bellisi-mo (1993) hypothesized that there would be no gender difference in atti-tudes toward computers. In a limited sample of 32 middle and high school students, they found no gender differ-ence in computer use for word process-ing. If word processing, which replaced secretarial typing, is perceived as a

female-oriented activity, then these findings support the gender constancy theory. Whereas Newman et al. (1995) found that women who were attracted to female-oriented activities had a more negative attitude toward computers, Sachs and Bellisimo differentiated com-puter skills and found no gender differ-ence in a particular computing activity.

In more recent research, Atan, Azli, Rahman, and Idrus (2002) found that there were no gender differences in the usage of general computer software as well as networking software. Addition-ally, Creamer, Burger, and Meszaros (2004) found no significant differences between computer use by women and that by men.

This contradiction of the existence of a gender gap can be explained by the type of computer tasks measured. The scales used in these studies vary widely. When a scale measures only the most basic computer skills (e.g., how to turn on a computer, how to create a folder using the operating system, typing using a word processor), the gender gap appears to have dissipated. However, when a scale measures more advanced user skills and varied applications, then the gap seems to reappear. Volman and van Eck (2001) noted that gender differ-ences must be analyzed in the context of different types of computer applications.

Research Question and Hypothesis Development

As computer technology changes, students need to expand their computer knowledge and ability to meet the tech-nology needs of businesses and not-for-profit organizations. Business students in college today are expected to develop a sufficient level of computer proficien-cy so they can quickly adapt to different computer systems within the business environment. This requires that they are confident in their ability to adopt and use computer technology.

We investigated the gender constancy theory to explore the impact of evolving technology on gender disparity. As tech-nology advances to allow computers to be used for a variety of functions, will females develop more positive attitudes toward computers and increase their computer usage? Previous literature has

focused on general computing self-effi-cacy. Based on the social cognitive the-ory and established methodology of self-efficacy reporting, we will provide an analysis of gender differences in computing self-efficacy over a variety of technological skills needed in today’s business environment.

We investigated the contradictions found in the research relating to the computing gender gap and examined the various types of computing skills that are expected of students in order to perform well in the business environ-ment (Stephens & Shotick, 2002) to determine if certain computer software tasks are gender-specific and if those skills represent a gender gap in technol-ogy. The hypothesis that was tested in this research was:

H1: Male students and female students have significantly different business com-puter self-efficacy in regard to the perfor-mance of specific business-related com-puter tasks.

METHOD

The scale used for this research meets two necessary criteria: It measures user skills currently needed in business and explores both basic and advanced skills in a variety of applications used in the business world. For this research, we used the business computer self-efficacy scale, which we developed (Stephens & Shotick, 2002). Following the guide-lines established by researchers in the study of self-efficacy, the scale uses a composite measure of magnitude and strength (Bandura, 1977). These scales, which are commonly used in social sci-ence research, attempt to determine the direction (magnitude) and strength of people’s beliefs (Lodge, 1981). This form of self-efficacy scale has been shown to provide the best correlations with goals and performance in research (Cassidy & Eachus, 2002; Lee & Bobko, 1994).

We administered the scale to 137 incoming freshmen at a medium-sized private midwestern university. We asked students to assess their ability to perform a variety of specific computer tasks, including both basic and advanced skills (101 specific tasks, are included in the

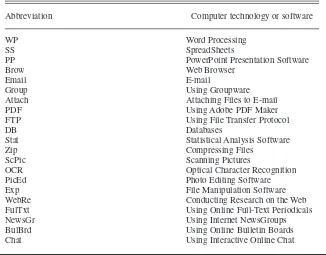

scale). The BCSE is a Likert scale based on a range of 0 to 5. If students state that they have no ability to perform a specif-ic task, then the score is zero. If students state that they can perform the task, then they are asked to assess their ability to successfully complete the task on a 1 to 5 scale (1 = very little ability; 5 = very good ability). This is a standard self-effi-cacy measure that captures both magni-tude and strength. An aggregate score is created for a student for a specific soft-ware application by calculating the aver-age response for all the tasks (basic to advanced). The business-related tech-nology and software examined by the scale include those found in Table 1.

Student gender distribution was almost evenly divided (68 men, 69 women). All of the students except for one male student indicated that they had computers (sometimes multiple com-puters) at home. We asked the students to state the number of programming classes that they had taken in high school or the number of classes that they had taken that involved using com-puter technology. Nearly 80% of the male students indicated that they had used computer technology in courses in high school and approximately 55% indicated that they had taken computer

programming courses. By comparison, 75% of the women had used computer technology in high school and 46% stat-ed that they had receivstat-ed computer pro-gramming training.

RESULTS

To test the hypothesis for gender dif-ferences on specific software or techno-logical skills, we calculated the average self-efficacy scores for each task or skill for all students (see Table 2). Using a pooled variance ttest, we estimated sig-nificant gender differences in students’ perceptions of their ability to use a par-ticular software package or technology. There were 13 specific software or technology skills in which male students rated their level of confidence signifi-cantly higher than female students. These were: (a) using spreadsheets; (b) using PowerPoint; (c) using groupware; (d) attaching files to e-mail; (e) creating PDFs; (f) using a Web browser; (g) using FTP; (h) calculating statistics; (i) zip-ping files; (j) subscribing to news groups; (k) using bulletin boards; (l) conducting file manipulation; and (m) performing optical character recogni-tion. The similarity of these tasks is that they are more technical and more

math-ematical in nature than the remaining tasks. These results support Mira’s (1987) claim that women are less profi-cient than men at performing those tasks that society associates with male charac-teristics (e.g., technical, mathematical). Although we found no significant gender differences among the remain-ing eight computer tasks, male students did have higher average levels of confi-dence in their ability to perform them than did the female students. These tasks included: (a) word processing; (b) using e-mail; (c) working with a data-base; (d) scanning pictures; (e) con-ducting research on the Internet; (f) viewing full-text articles online; (g) photo editing; and (h) navigating a chat room. A common theme of these tasks is that they consist primarily of com-munication functions. As computer technology becomes less technical and more practical in terms of sending and retrieving information, the gender dis-parity will dissolve. Shotick and Lump-kin (2001) found that the vast majority (as high as 90%) of students indicated that they learned specific computer

TABLE 1. Computer Technology and Software From Which Tasks Were Developed

Abbreviation Computer technology or software

WP Word Processing

SS SpreadSheets

PP PowerPoint Presentation Software

Brow Web Browser

Email E-mail

Group Using Groupware

Attach Attaching Files to E-mail

PDF Using Adobe PDF Maker

FTP Using File Transfer Protocol

DB Databases

Stat Statistical Analysis Software

Zip Compressing Files

ScPic Scanning Pictures

OCR Optical Character Recognition

PicEd Photo Editing Software

Exp File Manipulation Software

WebRe Conducting Research on the Web FulTxt Using Online Full-Text Periodicals

NewsGr Using Internet NewsGroups

BulBrd Using Online Bulletin Boards Chat Using Interactive Online Chat

TABLE 2. Male and Female Students’ Mean Ratings of Self-Efficacy for Computer Tasks

Task Malesa Femalesb

WP 3.76 3.71

SS* 3.13 2.75

PP* 3.05 2.66

Brow* 3.51 3.04 Email 3.78 3.77 Group* 1.56 0.89 Attach* 3.10 2.71

PDF* 1.97 1.26

FTP* 1.50 0.90

DB 2.40 2.20

Stat* 2.31 1.78

Zip* 2.12 1.48

ScPic 2.97 2.74

OCR* 2.19 1.78

PicEd 2.47 2.26

Exp* 1.93 1.09

WebRe 3.79 3.68 FulTxt 3.21 2.93 NewsGr* 2.68 1.94 BulBrd* 2.78 2.20

Chat 3.47 3.36

an= 68. bn= 69.

*p< .05.

applications through personal use. Communication applications are more conducive to self-teaching. Therefore, if most students become more familiar with applications through personal use, then more women should gain confi-dence in their abilities to perform cer-tain computer tasks through greater personal use of those applications.

DISCUSSION

H1 was partially supported by the data. Compared with female students, male students rated their ability higher in more than half of the computer tasks. Male students rated their ability on nearly 62% of the 21 tasks significantly higher than did female students. These computer applications were either more technical in nature or had limited uses. If female students use these tasks less frequently than male students, then they are likely to rate their self-efficacy for those specific tasks lower than men do.

A subtler difference between male and female students is that the types of computer tasks for which we found no significant differences were communi-cation forms of computer work (e.g., word processing, transmitting e-mail messages, researching information on the Internet, scanning and editing pho-tographs). These tasks provide direct dissemination of information rather than involve calculating information.

The more technical and complex computer tasks, such as file transfer protocol, file management, using spreadsheets, and computing statistics, provide an efficient method of calculat-ing or manipulatcalculat-ing data. Male stu-dents rated their confidence to perform these tasks significantly higher than did the female students. This study offers continued support for the gender schema theory and the notion that only when education encourages both male and female students to engage in tech-nology activities at an early age will the inequity dissipate.

In the meantime, colleges must strive to make more of an effort to train female students to be confident in using com-puter technology. Because we found gender differences at the task level, business technology instructors should make every effort to stratify their

con-tent, delivery, assignments, and support to allow females (if necessary) to get caught up on the basic technology appli-cations before moving to a more advanced level (Messineo & DeOllos, 2005). Wasburn (2004) provides 10 strategies for making technology teach-ing more conducive for female students. Similarly, Mathis (2002) offers sugges-tions for institusugges-tions of higher education to improve female students’ computer self-efficacy. Additionally, business col-leges should continue to offer an intro-ductory or remedial course to those stu-dents who need additional training to be at a similar level of competence as their peers. However, to require an introduc-tory course for all students could create frustration among those students who have developed advanced competencies in computer technologies, or advanced students might intimidate those who are not yet at a similar skill level.

Thus, business schools need to design and administer a survey instrument to place students in courses with various levels of computer technology require-ments. Because electronic survey instruments are more available, this process can be instituted with a mini-mum of resource expenditures. To pre-pare all graduates for the technology-savvy business environment, business schools must continue to provide oppor-tunities for women to enhance their computer confidence. This will create a more diverse and technologically-equi-table workplace.

The business workplace will continue to place emphasis on hiring computer-literate employees. Business colleges must respond to this need of business employers by preparing their students to be proficient in computer applications in business. Because the business environ-ment continues to rely upon efficient computer systems, business colleges must continue to advance self-efficacy of computer skills for all students. To do so will prepare students to meet the ever-changing technology applications. Busi-ness deans or administrators cannot assume that all students enter college with basic computer technology, nor should they assume that male and female students have similar technology skills. At the same time, business deans or administrators must be cautious not to

stereotype female students as technolog-ically inferior to male students. How-ever, they may need to provide more opportunities for female students to interact with computers and to use appli-cations with which they are unfamiliar.

NOTE

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Joyce Shotick, Executive Director of the Center for Student Support Services, Bradley University, 1501 W. Bradley Avenue, Bradley University, Peoria, IL 61625.

E-mail: jas@bradley.edu

REFERENCES

Agosto, D. (2004). Using gender schema theory to examine gender equity in computing: A prelim-inary study. Journal of Women & Minorities in Science & Engineering, 10(1), 37–53. Atan, H., Azli, N., Rahman, Z., & Idrus, R.

(2002). Computers in distance education: Gen-der differences in self-perceived computer com-petencies. Journal of Educational Media, 27(3), 123–135.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a uni-fying theory of behavioral change. Psychologi-cal Review, 84,191–215.

Bem, S. (1987). Probing the promise of androgy-ny. In M. R. Walsh (Ed.), The psychology of

women: Ongoing debates(pp. 206–225). New

Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Bryson, M., Petrina, S., & Braundy, M. (2003). Conditions for success: Gender in technology-intensive courses in British Columbia secondary schools. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathe-matics and Technology Education, 3,185–193. Bunderson, E., & Christensen, M. (1995). An

analysis of retention problems for female stu-dents in university computer science programs.

Journal of Research on Computing in Educa-tion, 28(1), 1–18.

Cassidy, S., & Eachus, P. (2002). Developing the computer user self-efficacy scale: Investigating the relationship between computer self-effica-cy, gender and experience with computers.

Journal of Educational Computing Research, 26, 133–153.

Chen, M. (1986). Gender and computers: The ben-eficial effects of experience on attitudes. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 2, 265–282. Compeau, D., Higgins, C., & Huff, S. (1999). Social cognitive theory and individual reactions to computing technology: A longitudinal study.

MIS Quarterly, 23, 145–158.

Creamer, E., Burger, C., & Meszaros, P. (2004). Characteristics of high school and college women interested in information technology.

Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering, 10, 67–78.

Dattero, R., & Galup, S. (2004). Programming languages and gender. Communications of the ACM, 47(1), 99–102.

Ferguson, K. (2000, June 5). Cisco high. Business Week ebiz, EB102–EB104.

Harrison, A., Rainer, R., & Hochwarter, W. (1997). Gender differences in computing activ-ities. Journal of Social Behavior and Personal-ity, 12, 849–869.

Koohang, A. (1989). A study of attitudes toward computers: Anxiety, confidence, liking, and perception of usefulness. Journal of Research

on Computing in Education, 22,137–150. Lee, C., Bobko, P. 1994. Self-efficacy beliefs:

Comparison of five measures. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 364–369.

Lodge, M. (1981). Magnitude scaling: Quantita-tive measurement of opinions. London: Sage. Mathis, S. (2002). Improving first-year women

undergraduates’ perceptions of their computer skills. TechTrends, 46(6), 27–29.

Messineo, M., & DeOllos, I. (2005). Are we assuming too much? Exploring students’ per-ceptions of their computer competence. College Teaching, 53(2), 50–55.

Mira, I. (1987). The relationship of computer self-efficacy expectations to computer interest and

course enrollment in college. Sex Roles, 16, 303–311.

Newman, L., Cooper, J., & Ruble, D. (1995). Gen-der and computers, II: The interactive effects of knowledge and constancy on gender-stereo-typed attitudes. Sex Roles, 23, 325–349. Sachs, C., & Bellisimo, Y. (1993). Attitudes

toward computers and computer use: The issue of gender. Journal of Research on Computing in Education, 26, 256–270.

Shotick, J., & Lumpkin, J. (2001). Computer profi-ciency: Are students ready for college?Paper pre-sented at the International Business Education and Technology Conference, Cancun, Mexico. Stephens, P., & Shotick, J. (2002). Computer

liter-acy and incoming business students: Assess-ment, design, and definition of a skill set. Issues in Information Systems, 2, 460–466.

Volman, M., & van Eck, E. (2001). Gender equity in information technology in education: The sec-ond decade. Review of Educational Research, 71, 613–634.

Wasburn, M. (2004). Is your classroom woman-friendly? College Teaching, 52, 156–158. Wilder, G., Mackie, D., & Cooper, J. (1985).

Gen-der and computers: Two surveys of computer-related attitudes. Sex Roles, 13, 215–228. Young, B. (2000). Gender differences in student

attitudes toward computers. Journal of Research on Computing in Education, 33,204–217.