Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 19 January 2016, At: 19:50

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

The struggle to regain effective government under

democracy in Indonesia

Ross H. Mcleod

To cite this article: Ross H. Mcleod (2005) The struggle to regain effective government under democracy in Indonesia , Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 41:3, 367-386, DOI: 10.1080/00074910500117289

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910500117289

Published online: 18 Jan 2007.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 487

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/05/030367-20 © 2005 Indonesia Project ANU DOI: 10.1080/00074910500117289

α∗Much of this paper was written while the author was a visitor at the School of Advanced

International Studies, Johns Hopkins University. The author is grateful to John Bresnan, Greg Fealy, Karl Jackson, Hugh Patrick, Bridget Welsh and two referees for their insight-ful comments, and to audiences at Columbia, Harvard and Johns Hopkins Universities to which earlier versions of this paper were presented.

THE STRUGGLE TO REGAIN EFFECTIVE GOVERNMENT

UNDER DEMOCRACY IN INDONESIA

Ross H. McLeoda*

Australian National University

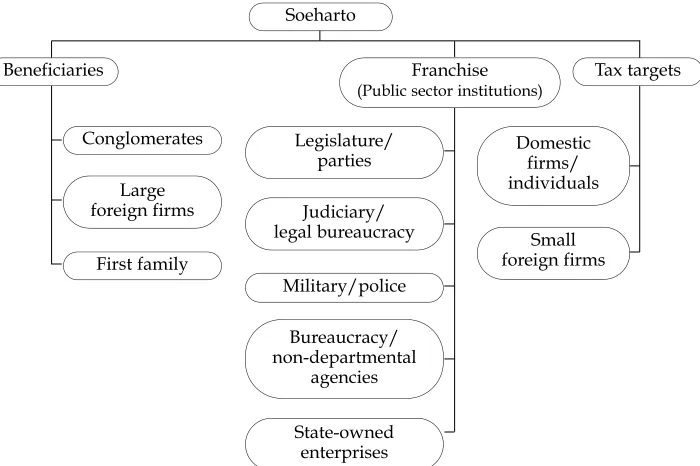

With Soeharto’s demise, Indonesia gained democracy but lost effective govern-ment. A return to sustained, rapid economic growth will require an overhaul of Indonesia’s bureaucracy and judiciary which, along with the legislatures, the mili-tary and the state-owned enterprises, had been co-opted by the former president into his economy-wide ‘franchise’—a system of government designed to redistrib-ute income and wealth from the weak to the strong while maintaining rapid growth. This franchise has disintegrated, its various component parts now work-ing at cross-purposes rather than in mutually reinforcwork-ing fashion. The result has been a significant decline in the security of property rights and, in turn, the contin-ued postponement of a sustained economic rebound. To reform the civil service it will be necessary to undertake a radical overhaul of its personnel management practices and salary structures, so as to provide strong incentives for officials to work in the public interest.

INTRODUCTION

Indonesia’s long-serving president, Soeharto, became more unpopular the longer he remained in office. The economic crisis that began in mid-1997 provided the conditions under which at last he was able to be forced out, only a couple of months after he had been elected unopposed to a seventh five-year term. Since then the country has been able to manage a relatively peaceful transition to a more genuine democracy. The first stage of this began with the formal handover of power by Soeharto to his deputy, B.J. Habibie, in May 1998. The second involved the holding of elections for the parliament in June 1999, and the subse-quent indirect election of Abdurrahman Wahid by the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR) as the first president of the new democratic era. The third saw the dismissal of Wahid in July 2001 and his replacement by Megawati Soekarno-putri, also by the MPR. The fourth stage encompassed a further general election, followed by Indonesia’s first direct presidential election, in 2004, resulting in the appointment of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY).

Macroeconomic conditions have stabilised after the astonishing upheaval of the 1997–98 crisis, which saw GDP fall by 18% in the fourth quarter of 1998

1A further consideration is the extent to which the legislatures, answerable to the general

public at national, provincial and district levels, hinder the operations of the bureaucracy. Some mention of this is made below, but the main emphasis here is on the civil service (including the judiciary), which is under the direct control of governments.

compared with a year earlier. The exchange rate settled at close to Rp 8,500/$ in the second half of 2003—having risen as far as Rp 15,000/$ in 1998—before weakening somewhat; in the year to mid-2005 it ranged between Rp 9,000/$ and Rp 9,500/$ for most of the time. Inflation, although still rather high relative to that of Indonesia’s neighbours, is back to levels that had become the norm prior to the crisis, and interest rates have declined to below pre-crisis levels. But cur-rent forecasts are for growth at around 6.0% per annum in 2005—somewhat slower than the average rate maintained over three decades of Soeharto’s rule. With population growth running at about 1.5% per annum, per capita incomes seem likely to grow at only around 4.5% annually—three-quarters the rate of 6.0% recorded during the four pre-crisis years. At this pre-crisis rate, average incomes double every 12 years; at the currently projected rate it takes a third as long again. Accelerating economic growth further is therefore crucially important for poverty reduction.

More important, it cannot simply be assumed that even this modest projected growth rate can be maintained into the future. Two important economic indica-tors are the absolute and relative levels of investment. Seven years after the crisis began, the former was languishing at just 80% of its pre-crisis level, and the lat-ter at 18% of GDP, compared with 30% pre-crisis. Some improvement has occurred more recently, raising the investment to GDP ratio to 22%, but this still leaves a long way to go to restore this ratio to its pre-crisis level. Business invest-ment’s slowness to recover suggests a lack of confidence that Indonesia’s new democracy will give rise to an effective government capable of doing the things needed to complement the functioning of the private sector.

Most of the discussion about how to return Indonesia to its previous high-growth trajectory tends to propose lists of policies that would support this objec-tive (and of those that would conflict with it). But this ignores the fundamental reality that whether sensible policies will be chosen, and whether they will be implemented effectively, depends on the quality of the bureaucracy.1Bluntly put,

we cannot expect significant improvement in the policy environment if the bureaucracy remains dysfunctional.

With these comments as background, the main aims of this paper are: first, to explain why, and in what sense, Soeharto’s regime was effective, and why subse-quent governments have been much less effective; and second, to suggest the nature of reforms needed if its effectiveness is to be matched or surpassed, and to discuss other kinds of reform initiatives already under way.

I shall argue here that with Soeharto’s demise, Indonesia gained democracy but lost effective government. By gaining democracy I mean that the people now have the genuine opportunity to vote out incumbent governments at regular intervals, and I interpret effective government in a limited and purely economic sense to mean doing what is needed to achieve rapid growth—with the expecta-tion that the benefits of growth will be widely spread amongst the populaexpecta-tion, as was the case during the Soeharto era. Specifically, I emphasise that rapid

2Flood control, drainage and sewerage systems were ignored, however (McLeod 2005a). 3A similar argument has been put in relation to priorities that need to be followed in

estab-lishing a new democratic regime in post-war Iraq (McDougall 2003).

nomic growth depends on a complementary relationship between the private and public sectors, in which the public sector provides things desired by the pub-lic but which the private sector is not able to produce.

The provision and maintenance of physical infrastructure by the public sector is clearly important, including roads, ports, airports, storm-water drainage and flood control, sewerage and so on. Most of this was given considerable promi-nence at an infrastructure summit in Bali in mid-January 2005 after several years of serious neglect (World Bank 2005: table 3.4; Soesastro and Atje 2005).2Beyond

this there is room for debate as to what other things governments should provide. There can be no doubt, however, that one of the most important tasks of the pub-lic sector is to ensure the rule of law and the security of property.3In turn, this

requires the drafting and enactment of laws and the provision of the means to enforce them: a judiciary, a legal bureaucracy (including a public prosecutor) and a police force. The weaker the rule of law and the security of property, the weaker is the incentive to invest and to work. As O’Driscoll and Hoskins (2003: 7) put it:

Once stated, the intellectual argument for the importance of property rights is com-pelling. Why does an individual invest unless to gain something for himself and his family? How can he ensure that gains flowing from his activity be appropriated and secured other than through a system of well-defined property rights?

In turn, since economic growth depends on investment and the supply of effort by individuals, economic performance of an economy overall can be expected to be, and is, strongly correlated with the security of property (Roll and Talbott 2003: 15–16).

THE FUNDAMENTAL DETERMINANTS OF ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE

It is a truism that the overall performance of any organisation or regime depends on the performance of the individuals that comprise it, other things equal. In turn, individuals’ performance depends on the strength of the incentives they face, both positive and negative. I shall argue that the incentives for good per-formance in the public sector institutions during the Soeharto era were strong— relative toSoeharto’sobjectives, which happened to coincide largely, though not entirely, with society’s objectives. By contrast, the incentives for good perform-ance in those institutions subsequently have become weak—relative to society’s

objectives. The decline in Indonesia’s economic performance since Soeharto’s demise can be explained by this change in the structure of incentives facing offi-cials in the public sector institutions, such that they no longer have much motiva-tion to do what is necessary to promote rapid growth of the economy.

Soeharto’s Franchise System of Government

Soeharto created incentives for effective government within what I have described elsewhere as a ‘franchise’ system (McLeod 2000). A more descriptive, if

Soeharto

Tax targets

Conglomerates

Large foreign firms

First family

State-owned enterprises Legislature/

parties

Judiciary/ legal bureaucracy

Military/police

Bureaucracy/ non-departmental

agencies

Domestic firms/ individuals

Small foreign firms Beneficiaries Franchise

(Public sector institutions)

FIGURE 1 The Soeharto Franchise

4Liddle (1985: 71) refers to the political structure of the New Order as ‘a

steeply-ascend-ing pyramid in which the heights are thoroughly dominated by a ssteeply-ascend-ingle office, the presi-dency’. Crouch (1991: 57) refers simply to ‘Soeharto’s patronage network’.

5The DPR is the People’s Representative Council, or House of Representatives.

6Liddle (1985: 74) refers similarly to ‘the building of performance-based support within

the pyramid’.

cumbersome, title would be ‘multi-branch, multi-level franchise‘ (figure 1).4The

branches of the franchise included the legislature (MPR, DPR5and tame political

parties); the judiciary and the legal bureaucracy; the military/police; the bureau-cracy (including non-department agencies, especially the logistics agency, Bulog, and the central bank, Bank Indonesia); and the state-owned enterprises (SOEs), especially the giant oil company, Pertamina, and the state banks. Most of the branches encompassed a number of levels. Legislatures existed at national, provincial and district/municipality levels, while the bureaucracy extended right down to the villages. The hierarchy of the judiciary extended down from the Supreme Court through the High Court to the district courts. The army also had regional divisions, as did the state banks.

Like franchises in the world of business, the Soeharto franchise was designed to provide strong positive and negative incentives for its success. Key public sec-tor officials could rapidly become wealthy if they lived by its rules, but they could find themselves sidelined if they failed to perform well or if they worked against it.6It prospered by means of ‘private taxation’—that is, various forms of informal

taxation of individuals and firms. The ‘taxes’ imposed by franchisees were of two

7For example, a crony firm might be given a valuable concession to log natural forests, or

a monopoly on certain kinds of imports. Various rent generation mechanisms are dis-cussed in McLeod (2000: 155–6).

main types: extortion, and rents generated by the public sector through its eco-nomic policies and harvested by cronies of the regime (the ‘conglomerates’), members of the first family and large foreign firms7—these last three groups

being the major beneficiaries of the system (other than the franchisees them-selves). By and large, this taxation was levied at a low rate on a wide ‘tax base’ that comprised a large part of the economy as a whole; it operated in conjunction with economic policies that helped the private sector to generate rapid economic growth in order that this tax base would also grow rapidly. Thus there was a close correspondence between the interests of Soeharto’s franchise and the interests of the general public, even though the effect of private taxation was to redistribute some income and wealth from the weak to the strong: both the franchise and the public stood to gain from broadly sound economic policies that generated rapid growth.

To see this, suppose all individuals’ incomes rise by 5% prior to imposition of a ‘private tax’ of 0.1% on the incomes of 99% of the population. The ‘tax revenue’ is then redistributed to the other 1% (i.e. the members and beneficiaries of the franchise). If the latter small group had incomes, say, 10 times as great as those in the large group to begin with, it is easy to show that their incomes will grow by about 6% in total. But the large ‘poor’ group is also better off than before, with a net gain of approximately 4.9%—notwithstanding redistribution from it to the ‘rich’. The growth of the economy—to a considerable extent the consequence of sound economic policies—is beneficial to both groups.

Despite the legendary corruption and incompetence of the legal system and the bureaucracy, the rules of the game enforced by the franchisor (Soeharto) were such that property rights were relatively secure for the majority of the popula-tion. (This is not to deny many instances of effective expropriation of land, often through violence or the threat of it, by politically well-connected real estate devel-opers, plantation owners, and the like, but the number of individuals directly affected by this would appear to be small relative to the total population.) Liddle argues that periodic crackdowns on corruption ‘[encouraged] the public to believe that the government [was] at least well intentioned‘ (Liddle 1985: 78). No doubt there is something in this, but I would argue also that Soeharto appreciated that excessive infringement of property rights by individual franchisees (i.e. imposition of excessive levels of private taxation) was inimical to the interests of the franchise as a whole. The replacement of the notoriously corrupt customs service by a private company in 1985—which turned out to be temporary, notwithstanding the obvious improvement in the functioning of Indonesia’s ports—can be interpreted plausibly in this light (Elson 2001: 247).

THE DEMISE OF THE FRANCHISE

The 1997–98 economic crisis demonstrated that members and beneficiaries of the franchise could no longer rely on it to deliver effective government, thus trigger-ing its disintegration, and ushertrigger-ing in the era of democracy. In principle, if the

8After years of strong private capital inflows, the crisis that emerged in 1997 saw a

dra-matic turn-around. Heavy capital outflow was experienced for the next six years before net inflows returned in 2004 (McLeod 2005a: 136).

franchisees had been able to come together at the time to agree upon a replace-ment for Soeharto as ‘owner’ of the franchise, the system might have been able to continue under new leadership. In reality, B.J. Habibie briefly succeeded Soeharto as ‘owner’, but was under no illusion that he had the political skills, power and ruthlessness that would be needed to rebuild the same kind of system, even if he had wanted to do so: it was obvious that few if any of the franchisees were will-ing to defer to him as they had to the former leader (whether out of respect, loy-alty, the hope of advancement, or fear).

Habibie could not rely on the hundreds of MPR members appointed by Soe-harto, nor those representing the armed forces, to allow him to stay on as presi-dent. The only possible way to stay in office was to hold a general election in the hope that the people would give him a mandate to continue in the job. By allow-ing a genuine contest for seats in the DPR among the existallow-ing political parties and a plethora of other newly established ones, he destroyed the key feature of the franchise—mutual support among its constituents in favour of a common cause. Tainted by its close association with Soeharto, and without strong army backing, the Golkar party (the government party under Soeharto) could not dominate the 1999 election as it had previous ones. It lost a large proportion of its seats in the DPR to other parties—three of which each had credible candidates to take over the presidency. Habibie failed to gain his mandate, and the franchise crumpled.

Outside the legislature, the other former branches of the franchise also began to work at cross-purposes rather than as a multi-faceted but mutually supporting whole. This soon resulted in increasingly high levels of private taxation in some areas of the economy. In other words, property rights became less secure for both firms and individuals, and this was manifested in the shift of capital offshore8

and the reluctance of the private sector to undertake new investment. Domestic and foreign firms that previously harvested rents generated by the franchise could no longer be confident of their ability to do so in an environment in which the leadership of government had become genuinely subject to change at regular intervals, and they therefore had much weaker incentives to invest in Indonesia. Firms that previously put up with extortion because it remained relatively light, and because these were times of steadily increasing prosperity, now found it more threatening in the absence of centralised control. Banks that would have liked to be lending more were afraid to do so because they could not rely on the courts to enforce their loan contracts.

The flowering of democracy itself also imposed additional costs on the corpo-rate sector. Like a monopolist with no need to spend heavily on advertising since it has no competitors to keep at bay, Soeharto had relatively little need to ‘tax’ cor-porations to fund election campaigns: the whole election process was a charade in which Golkar could not lose. But now there were several parties with enough electoral support to be considered serious contenders for membership of govern-ing coalitions, and the high value of the spoils of office meant that most were pre-pared to spend heavily on their election campaigns. The unpredictability of the

9Note that avoiding privatisation in order to maintain control of the state enterprise cash

cows condemns this significant part of the economy to sub-standard performance.

10‘Corruption ”from State Palace to Political Parties”’, Jakarta Post, 23/1/2001. 11‘Deep Pockets’, Tempo Magazine, 7/10/2002.

outcome, in stark contrast with Soeharto era elections, meant that many compa-nies made contributions to some, perhaps several, of these parties in order to try to secure their fortunes through each phase of the electoral cycle, as the infamous Bank Bali corruption case suggests (Fane 2000: 42). And no doubt state enter-prises were also privately taxed for the same purpose—hence the lack of political support for privatisation, which was intended to be a key feature of the IMF’s cri-sis recovery program for Indonesia.9

There are many other examples of changing behaviour on the part of the branches of the former franchise that show how they have lost their coherence, and thus have become an obstacle to economic recovery, with the advent of democracy. In addition to increasing the net rate of private tax imposed on firms and individuals by corrupt officials, and increasing the degree of uncertainty about property rights and the future course of development, the effect of the col-lapse of the franchise has been to increase the extent of uncontrolled, environ-mentally damaging exploitation of natural resources (see various chapters in Resosudarmo 2005) and to constrain the ability of more conscientious members of the government and the bureaucracy to implement sound economic policies. Consider the following examples.

An Extortive Legislature

Since the fall of Soeharto the relationship between the legislature and the execu-tive (at the national level) has changed dramatically (Sherlock 2003: 19–21). Before, the parties and individual members owed their presence to Soeharto’s favour. Their primary role was to re-elect him, in return for which they received a modest share of the spoils of office. Now, with a new president in place—but with parliament having the power to remove him—the relationship shifted from cooperation to confrontation. It is one of the functions of legislatures in democra-cies to protect the interests of the public against mistakes and malfeasance on the part of the executive, but in this case much of the new activism in the DPR was intended to increase its members’ share of the cake.

The people’s representatives were not slow to seize upon the opportunity to extort funds from the bureaucracy (and thus, indirectly, from the general public) as it attempted to carry on the business of government—introducing new laws and regulations; implementing budgetary decisions such as the removal or reduction of subsidies and the divestment of state-owned enterprises; the appointment of individuals to positions such as top military posts, ambassador-ships and the governorship of the central bank; and, in particular, the attempts of IBRA, the Indonesian Bank Restructuring Agency, to divest its large portfolio of bank and corporate assets.10It did not escape the media’s attention that members

of parliament quickly came to appear much better dressed, and to be driving around in much more expensive vehicles, than before.11

12IBRA was wound up on schedule in February 2004, having recovered only about 25%

of the funds the government had put into the collapsed banking system (McLeod 2005b: 43–4).

13‘Court Verdict on Manulife Upsets Canadians’, Jakarta Post, 14/6/2002. 14‘Manulife Judges Exonerated’, Laksamana.Net, 22/1/2003.

15‘Tri Polyta Indonesia Asks Court to Cancel Bond Claim’, Bloomberg, 9/4/2003.

A Judiciary Out of Control

The judiciary became much more prominent in the wake of the crisis, primarily because so many firms and banks became insolvent—or merely stopped servic-ing their debts. Large-scale bankruptcy had rarely been an issue in the pre-crisis era, but now many creditors suddenly began to file bankruptcy claims against defaulting debtors, and the judiciary found itself in a position in which it had far greater opportunities than before to benefit financially from the larger and more numerous cases coming before it. The biggest creditor of all was IBRA. This new part of the bureaucracy was established in 1998, and given the task of recovering as much as possible of the government’s outlays on bailing out the banks. But it found itself in an unequal contest of strength with the judiciary, which was only too willing to exploit its position in order to extract large bribes from the default-ers—at IBRA’s expense. This, in turn, created enormous pressure on the budget, seriously compromising the government’s ability to undertake the expenditures necessary to keep the economy in good shape (Pangestu and Goeltom 2001: 144)—not to mention imposing huge costs on the general public.12

Another party to suffer has been the foreign investment community, which used to rely heavily on the ‘franchise connection’ for the protection of its assets and activities in Indonesia (Cole and Slade 1998: 65), but has found the going very tough in the corrupt court system since Soeharto’s demise. One well-known example is the Canadian insurance company, Manulife, whose former joint ven-ture partner was able to persuade the court to declare Manulife Indonesia bank-rupt, although it clearly was not.13Eventually this decision was overturned, but

only after considerable pressure was brought to bear—amongst others, by the Canadian government.14A later case involved Tri Polyta Indonesia, which not

only sought to have the courts invalidate $185 million worth of bonds it had issued overseas before the crisis began, but also sued the bondholders for more than $600 million for the return of interest previously paid and for ‘emotional dis-tress caused to the company management‘.15The patent absurdity of this claim is

an indication of how dysfunctional the judiciary had become. Instead of protect-ing property rights it began to be used as an instrument of expropriation, as is apparent from the later annulment of the entire Tri Polyta bond transaction by the Serang (West Java) District Court (Donnan 2004; Bisnis Indonesia, 13/5/2004). In cases such as these, this unholy alliance between the judiciary and domestic cap-ital conflicts with the efforts of Indonesia’s economic policy makers to persuade foreign capital to return, and thus to assist with economic recovery.

Newly Active Regional Governments

Since power and authority were so heavily concentrated at the centre under Soe-harto, one of the first priorities of the reform movement was the devolution of

16The spirit of article 33 of the constitution clearly requires that wealth derived from

nat-ural resources belongs equally to all Indonesians, regardless of where they live. This issue seems to have been totally ignored so far.

17In reality, the implementation of this aspect of the law seems to bear little resemblance

to what it appears to say (Fane 2003). Both the decentralisation laws were replaced with new ones in 2004, but without any significant impact on the aspects of their operation dis-cussed here.

18See, for example, ‘Knives Are Out for ”Skewering” the People’, Tempo Magazine, 22–28

April 2003; ‘Six Into One Does Go’, Tempo Magazine, 29 April – 5 May 2003.

some aspects of government to the regions—or ‘decentralisation’ as it is known in Indonesia. By quickly seizing the initiative here, Habibie hoped to gain kudos that would help him to retain the presidency (McLeod 2005b: 46). Just as allowing numerous parties to contest the election had contributed to horizontal fragmenta-tion of the franchise, devolving significant power and authority to lower levels of government would have contributed to its vertical fragmentation. In the event, the franchise had collapsed long before decentralisation began to be implemented. Two laws on decentralisation were among the flurry of new statutes enacted during Habibie’s term in office (Anwar 2001: 7–13): Laws 22 and 25 of 1999, on Regional Government and Fiscal Balance between the Centre and the Regions, respectively. A feature of the second of these was the extraordinary—and seem-ingly unconstitutional—decision to try to buy the support of resource-rich regions by agreeing to return large proportions of natural resource revenues to the provinces and districts where they originated.16In the past, oil and gas

rev-enues in particular had played a big part in financing government expenditure throughout the nation, especially on the construction and maintenance of infra-structure (Ravallion 1988: 54). At face value, Law 25/1999 greatly reduced the scope for a continuation of this, and thus provides a good example of parts of the old franchise now going their own way, regardless of the impact on other parts, and on the sense of nationhood in Indonesia.17

The devolution of some of the functions of government to provincial and dis-trict levels has meant that regional governments no longer regard themselves as subservient to, and dependent upon, the central government. In other words, they no longer see themselves as having to play by the rules of a central fran-chise—as indeed was the intention of the decentralisation reform. There are clear indications that regional government officials, like members of parliament at the national level, have adopted the attitude that the widespread opportunities for personal enrichment enjoyed hitherto by their central government counterparts have now shifted to the regional levels.18

One well-known example of this is the central government’s attempt to priva-tise its cement manufacturing company, PT Semen Gresik. A relatively small shareholding in this company had been divested some years ago to the Mexican company, Cemex (Cameron 1999: 25–6). At the time of this sale, Cemex was given an option to purchase a majority stake in the company. But when it moved to exercise this option, the provincial governments in West Sumatra and South Sulawesi, where two of the company’s major plants are located, moved to block the sale and, in effect, to seize control of the central government’s ownership stake (Deuster 2002: 11). The case helped to dampen what little enthusiasm the

19‘Charge Service’,Tempo Magazine, 25–31 March 2003.

20SMERU Newsletter, No. 03, July–September 2002, SMERU Research Institute, available

at <http://www.smeru.or.id/news2002.htm>.

Megawati government had for privatisation (Taufiqurrahman 2003), and was still in deadlock at the time of writing, notwithstanding some positive signs that emerged with the advent of the new Yudhoyono government (Kadga 2004).

In another case, regional (provincial and district) governments in East Kali-mantan, apparently acting partly on behalf of domestic private sector interests, have engaged in attempts to expropriate a majority stake in the foreign-owned mining company, PT Kaltim Prima Coal (Callick 2002a; Dodd 2001, 2003). The effective usurpation of the powers of the courts by these governments, and the implicit threat of extortion by the army, as in both Aceh and Papua,19have added

to the concerns of foreign investors generally. Domestic mining companies have also been affected, and have cut back significantly on their investments. In such circumstances it is not surprising that the mining sector has been stagnant for the last several years.

The Kaltim Prima episode had even wider implications for the economy, how-ever. The uncertainty created by the court attachment of the Tangguh natural gas field in Papua, which was owned by one of Kaltim Prima’s original shareholders, had the effect of preventing the sale or transfer of the gas field to any other party, thus making it difficult to raise the finance needed for its development. This action is plausibly blamed for the loss to Australia of a huge contract to supply China with natural gas—even though the attachment was eventually overturned after the then president intervened (Callick 2002b). It is interesting to note also that in its efforts to overcome the malign impact of its own courts, the govern-ment moved even further away from its commitgovern-ment to privatisation by agreeing to purchase (through a state-owned mining company) 20% of the 51% share of Kaltim Prima that was required to be divested under the terms of its establish-ment. The hope was that this would be more acceptable to the original owners than allowing the regional governments to acquire a majority stake in the com-pany. In the event, the owners took matters into their own hands and quickly sold their entire interest to a company owned by the family of Aburizal Bakrie (later to become coordinating minister for economics in the SBY government).

A further important aspect of the collapse of the franchise is the enthusiasm with which regional governments have begun to impose a range of taxes within, or at, their boundaries.20In some cases this is well intended, but no doubt in

oth-ers it is simply a manifestation of the fact that, by imposing formal taxes, the opportunity is created for officials to generate income for themselves by negoti-ating effective reductions or exemptions for the taxpaying entities in question (Kuncoro 2004: 336–9). In any case, there is no doubt that this has hindered recov-ery by making life more difficult for private firms.

Turf Wars between the Army and the Police

Another of the reforms of the Habibie era was to separate the police from the armed forces. This has led to a more overt rivalry between these two parts of the former franchise—in particular, between the police and the army—which bears

21‘Nine Hours in Binjai’, Tempo Magazine, 14/10/2002. An earlier episode in which the

army attacked police stations in Madiun resulted in two civilian deaths and numerous injuries (Jakarta Post, 18/9/2001).

22The impending surrender of their seats in the DPR was not even mentioned by Liddle

(2003), who argued that ‘… nothing fundamental has in fact changed since 1998. … A gov-ernment that does not pay its soldiers cannot control their actions.’

an interesting resemblance to the gang wars of the prohibition era in the US. This is not surprising. Both are involved with organised crime: gambling, prostitution and drug dealing, and with the practice of extortion, which is a natural extension of those activities (Weiss 2002). The competition between them from time to time breaks into the open, as in a case involving drug dealing in Sumatra in which a number of soldiers attacked a police station, killing several policemen.21The

busi-ness community can hardly ignore this kind of occurrence when it, itself, needs to rely on the police to protect its property rights. A police force that is heavily involved in organised crime is unlikely to perform this function effectively.

THE CHALLENGE OF REFORMASI:

REGAINING EFFECTIVE GOVERNMENT

It has become a cliché to observe that the strengthening of public sector institu-tions was given little emphasis during the Soeharto era. But it is important to appreciate that this was no oversight. On the contrary, it was precisely this that had helped make Soeharto strong and his extended family and cronies wealthy. His intention was to make himself safe from any attempt to remove him from office or to dilute his ability to make policy as he saw fit. Indonesia’s ‘democracy’ was a sham, in which there was no chance that Soeharto would be removed through the election process. Nor was there any chance that the legislature, the bureaucracy, the judiciary, the armed forces or the state-owned enterprises would put the interests of the people before those of the franchise.

Though the legislature and the election processes on which it is based have now been democratised, if ‘now’ is genuinely to become the era of reformasi, all the other public sector institutions will also need to be reformed. Reformasi

requires not only getting rid of Soeharto, but also either getting rid of, or chang-ing the behaviour of, a large proportion of his former franchisees. The difficulty of doing so has been underestimated, however. For example, many seemed to think that reforming the armed forces required little more than depriving them of their quota of seats in the DPR. This change was achieved in the 2004 general elec-tion, but in practical terms the army remains as strong as ever22—indeed, it is

arguably even stronger, now that Soeharto is not there to keep it under control.

PERSONNEL MANAGEMENT PRACTICES AND SALARIES AS THE KEY TO REFORM

Whereas the several consecutive Soeharto governments succeeded in generating rapid growth over some three decades, the replacement of his franchise system by a far more genuinely democratic regime has been followed by several years of much less satisfactory economic performance. Although investment activity

23A more precise statement of this principle would take into account the trade-off between

recruiting ‘better’ people and the extra cost of doing so.

24 This was reflected in a well-known aspect of public sector culture—namely, a

wide-spread awareness of differences in the availability of opportunities for graft; areas where such opportunities were abundant became known as ‘basah’ (wet).

finally began to pick up significantly around the end of 2004, it is too soon to know if this will be reflected in sustained rapid growth in output at rates similar to those achieved before the 1997–98 crisis. In the opinion of the writer this is unlikely, unless the new government of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono is able to extend democratic reform beyond the first step of implementing reasonably fair and open elections to encompass the creation of strong incentives for good per-formance in the public sector institutions, relative to society’s objectives.

It seems self-evident that the aims of any organisation will be best served if it can appoint the best possible person available to each position within it.23

Accordingly, the emphasis in organisations such as sporting teams and private sector enterprises is on encouraging fair and open competition for positions at all levels within them. That, of course, is fundamental to the notion of democracy itself, in which individuals and parties compete with each other to persuade vot-ers that they will do the best job of governing. Successful reform of Indonesia’s other public sector institutions (i.e. beyond the legislatures) will depend crucially on the adoption of a similar approach—the creation of an environment in which all individuals within them have strong incentives to compete by performing to the best of their ability.

The discussion that follows ignores the state enterprises, whose poor perform-ance mirrors that of the civil service. Suffice it to say here that the same broad principles of reform apply to both, although the author’s preferred course of action in the case of state-owned enterprises is to remove the problem by divest-ing them to the private sector. Reform of the military and the police is also highly desirable, not least because both organisations are partly responsible for insecu-rity of property rights—and therefore for impairing Indonesia’s economic per-formance—as a result of acts of both commission and omission. Space limitations do not permit adequate discussion of this issue here, however.

The inadequacies of Indonesia’s public sector institutions are a reflection of Soeharto’s practice of encouraging his franchisee officials to manage them in such a fashion that they could personally benefit by exploiting their positions. Within the logic of the franchise framework presented above, it would have made sense for him to keep basic salaries low, especially at the higher levels, in order to bring people into these positions who would be unconcerned about their basic salaries but would focus instead on the opportunities they would have to earn additional income—often illicit—as franchisees.24This has been manifested in the

prolifera-tion of addiprolifera-tional regular allowances for individuals in particular posiprolifera-tions; of ad hoc payments for attending meetings, conferences and so on; of payments for serving on a wide range of committees (in particular, those concerned with pro-curement); and of a range of benefits associated with special projects. Given a lack of transparency, access to many of these additional payments, and to participa-tion in straightforward graft and bureaucratic extorparticipa-tion, was condiparticipa-tional on the individual in question playing by Soeharto’s rules. Thus the president was able

25Thus the often heard argument that low salaries ‘force’ public sector officials to engage

in corruption is an insult to those who choose not to do so.

26 At present it is difficult even to discharge civil servants found guilty of corruption,

although there is now some suggestion that Law 43/1999 on public servants will be revised in order to speed up this process (Witular 2005).

27The current annual assessments of performance ‘are descriptive, and do not assess

per-formance against targets and objectives. They … cannot be considered as an instrument of accountability’ (ADB 2004: 59).

to co-opt officials within these institutions to serve his own interests by ensuring they had a common interest in the effective functioning of the franchise.

Many young people who had every intention of working well for the benefit of the public were also recruited to these institutions. Such individuals tended to languish in the ‘dry’ areas, and for the most part they found that the path to pro-motion was heavily restricted unless they wanted to buy into the franchise. Some of them did so, while others left to seek their livelihoods elsewhere. Many more simply accepted their fate, enduring a low standard of living, and forgoing any real opportunity for promotion to levels at which they were capable of function-ing effectively.25A few made their way up through the hierarchy by virtue of

Soe-harto’s recognition of the need for especial competence in at least some key areas of policy making.

Reforming Personnel Management

Performance-based competition for each position in an organisation is very dif-ferent from the process of automatic promotions, based on seniority, that is presently a fundamental characteristic of the Indonesian civil service (including the judiciary). When promotions are largely automatic, individuals have little incentive to perform better than their peers. Overstaffing at higher levels becomes the norm, since even poor performers are promoted rather than being either kept in their present positions or encouraged to leave. Those who do per-form well are frustrated by the lack of meaningful recognition of their efforts. This may result in their leaving the organisation for private sector jobs where they can expect to be rewarded appropriately, or simply becoming dispirited and significantly less productive as a result. At the same time, there is little incentive for individuals to increase their productivity by undertaking additional educa-tion and training, since in practice there is scant payoff in terms of salary increases or promotions.

Thorough reform of the civil service therefore requires radical changes to per-sonnel management practices, especially in relation to recruitment, promotion and discipline. Recruitment from outside the civil service should no longer be restricted to recent school and university graduates, and discipline should be understood to include bringing criminal charges against those found to have acted corruptly.26It will be essential to put considerably more emphasis on

per-formance appraisal27and to reform the processes of recruitment and promotion

so as to make them transparent and fair. Presumably these processes will involve formal selection and promotion committees, whose membership would be cho-sen so as to provide some element of outside scrutiny. Records would need to be kept of advertisements for the positions in question, applications for those

28Public sector salaries may be able to be kept a little below those in the private sector, to

the extent that employment in the former is seen to provide additional, non-pecuniary benefits.

29Filmer and Lindauer (2001) argue that the common perception that civil servants

gener-ally are greatly underpaid relative to the private sector is not supported by available evi-dence. They contend that low-level civil servants are actually somewhat better paid, in which case there is no reason to increase their salaries further.

30‘Jakarta To Jail Tax Dodgers without Trial’,Straits Times, 29/3/2003.

tions, and justifications by committees for their decisions. A further aid to trans-parency would be to make promotions and appointments subject to appeal by unsuccessful applicants. In other countries, procedures of this kind have taken years, if not decades, to evolve, and to become part of the corporate cultures of the organisations in question, so all of this clearly amounts to a massive and dif-ficult undertaking.

Reform also requires a far-reaching restructuring of the Soeharto franchise salary scales. Specifically, much more attractive salaries are needed at higher lev-els in the hierarchy in order to attract honest and well-motivated people, and to give civil servants an incentive to perform well in order to achieve promotion to higher levels. To a large extent this would merely involve rolling the complex array of allowances and semi-regular additional payments now received, along with basic salaries, into a single, transparent salary for each position. This has long been advocated; the fact that it has never been achieved suggests that many indi-viduals benefit from the utter lack of transparency in the current system.

The actual remuneration of many civil servants currently includes not only these various formal and semi-formal components but also the proceeds of cor-rupt activity, and so may be far above the sum of formal salary plus identifiable legitimate allowances. It is not necessary to set salaries that would match present-day official salaries augmented by typical earnings from graft and corruption, however. There are many people who would be willing to work in these institu-tions provided that their salaries were broadly in line with those of people in sim-ilar professions working in the private sector, but it will be impossible to attract a sufficient number unless this is so.28

Fiscal constraints do not constitute a reason for postponing the restructuring of salaries. In the first place, it is not necessary to increase remuneration across the board, but only at higher levels, where salaries fall well short of those for simi-larly skilled private sector managers and professionals.29 As we move up the

hierarchy of the relevant institutions the rapidly declining number of positions means that it is not out of the question to finance large increases in remuneration.

More importantly, however, provided these increases are accompanied by appropriate changes to personnel management practices, the cost of higher remu-neration will be covered by bringing about a significant improvement in the qual-ity of management. One of the most obvious areas where this can be seen is within the Ministry of Finance, and specifically within the taxation directorate and the customs service. It is well known that the ministry has failed to widen the income tax base or to extract taxpayers’ full tax liabilities from them,30and that the

cus-toms service is rife with corruption (Lingga 2002). Improving the quality of

31The government could also generate much more revenue from its marine resources if

reform of the navy resulted in a more serious effort to deal with illegal fishing activity; see ‘New Regulation in Works to Curb Illegal Fishing’, Jakarta Post, 10/3/2000.

32The proportion of public sector officials who have some involvement in petty

corrup-tion is so large that it would not be feasible to exclude them all from reappointment or pro-motion; the sensible approach would be to ignore the past in these cases, while making it very clear that even petty corruption would not be tolerated in the future.

sonnel and the incentives they face in this ministry alone could be expected to result in significantly increased tax revenues. Similar comments apply in relation to the forestry and mining ministries, which also have a record of considerable under-achievement in relation to the collection of natural resource royalties.31

Finally, with better management and a strong focus on discipline it can be expected that procurement throughout the public sector will become much more cost-efficient, resulting in large savings in outlays that would make fiscal room for the payment of higher salaries. For example, one of the high profile anti-corruption cases that emerged in mid-2005 stemmed from the payment of gratu-ities by firms that gained contracts to supply ink, paper, ballot boxes and the like for the elections in 2004. As appears to be customary practice in the bureaucracy, these funds were added to a ‘dana taktis’ (tactical or slush fund), then to be deployed for purposes that included ‘improving the welfare’ of officials of the election commission. Clearly, in the ideal situation in which there were no such kickbacks, supply prices would be cheaper, and the savings to the government could be used to pay transparently higher salaries to its employees.

Implementation Strategy

Civil service reform requires that a new salary structure be determined, based on an intensive study of comparable private sector employee remuneration, and that it be made public. The government would not provide automatic salary increases to incumbents, however. Instead the incumbents would be invited to reapply, in effect, for their own jobs—but at the new, higher salary levels—in competition with anybody else who wished to apply, whether from within or from outside the institution.

This in itself would be a highly significant break with the current practice of recruiting only at base levels—implying that higher levels can only be filled by promotion from within. This practice helped to strengthen Soeharto’s franchise by creating strong incentives for employees to act as their superiors wanted them to, since virtually the only path to career advancement was upwards within the individual’s present organisation. Seen in this light, Lindsey’s report of ‘aggres-sive opposition from the incumbent Supreme Court bench’ to the threatened appointment of an ‘outsider’ as chief justice is unsurprising (Lindsey 2001: 57). To offset resistance to this process in all the public sector institutions it may also be worthwhile in some cases to offer voluntary redundancy packages to incum-bents who might prefer retirement to going through this process. By changing this approach the government would make clear that it would not reward count-less public sector officials who had abused their positions in the past, or who had been appointed to their present positions on grounds other than their competence to do the job.32Rather, it would only pay the new salaries to the best individuals

33It is up to the people to choose their parliamentary representatives, of course, but with

a reformed bureaucracy and judiciary the government would be in a position to bring about further reform here, too, by taking firm action against members of parliament found to be involved in corrupt activity.

34Lindsey (2001: 51–2) also argued in favour of this approach in relation to the reform of

the judiciary. Alas, whether as a result of strenuous opposition from the incumbent Supreme Court judges, or of then president Wahid’s own second thoughts about the full implications of Indonesia having a more honest and capable judiciary, these hopes came to nothing.

available for the positions in question. At the same time, it would be important for the government to emphasise that the path to higher salaries would be through promotion—and that individuals could now expect to be promoted on merit.

Sequencing

If the proposed reform amounted to nothing more than salary increases, then all that would need to be done is to determine the new salary scales and implement them. However, the objective is to get the best available people into each position, and this entails the reassessment of appointments throughout all the public sec-tor institutions. Obviously it would not be feasible to undertake such an enor-mous task all at once. Moreover, at the very top levels, appointments would not follow the standard procedure of advertising positions and having selection com-mittees choose between applicants. At these levels, appointments will continue to be political, with choices made by presidents and their advisers.

In principle, an appropriate way to proceed would be for an incoming presi-dent to make all of the ministerial appointments, and perhaps additional appoint-ments at the top levels in each of the ministries (in consultation with the new ministers), and then to move in the same manner in relation to the judiciary, the military/police, and the SOEs.33Beyond that, the first task of those appointed to

these top positions would be to advertise and fill positions at the newly deter-mined salary scales for the next lower one or two levels—whether by re-appoint-ment of incumbents, promotions, or recruitre-appoint-ment from outside. Thus the procedure would be to work from the top down, appointing people at the new salaries, and then relying on them to repeat the process at the next levels down in the hierarchy.34

PROSPECTS FOR REFORM AND RECOVERY Current Reform Efforts

Current reform efforts rely on approaches quite different from those outlined above: training, and anti-corruption initiatives. The emphasis on training implic-itly assumes that public sector officials desire to further the public interest, but are prevented from doing so effectively by a lack of the necessary skills. In real-ity, the provision of training in a context in which officials’ legitimate remunera-tion is far below their earning power (given the extensive opportunities for corrupt conduct), and in which the link between performance and promotion is

35The Commission to Audit the Wealth of State Officials reported in mid-2002 that only

35% of judges, prosecutors and police officers had obeyed the directive to report their assets (Simanjuntak 2002).

36 Megawati’s then ally, Akbar Tanjung, secretary of coalition partner Golkar and DPR

chairman, was also permitted to continue in office even though having been found guilty of corruption; see ‘Court Upholds Tanjung Verdict’, Laksamana.Net, 17/1/2003.

37Earlier attempts to eliminate corruption under Soeharto were also almost entirely

cos-metic; they failed because Soeharto had no intention that they should succeed (Mackie 1970; Mubyarto 1984).

weak, is like pouring water into desert sand. It is simply naïve to expect officials to use their skills in the interests of the public unless they have appropriate incen-tives to do so.

Anti-corruption initiatives, such as establishment of the Commission to Audit the Wealth of State Officials, the Anti-Corruption Commission, the National Ombudsman’s Commission (Sherlock 2002) and, more recently, the Coordinating Team for Eliminating Corruption (Jakarta Post, 6/5/2005), assume that what is lacking is enforcement of the norms of proper behaviour. While such mechanisms have an important role to play, they are most likely to be effective in systems in which corruption and malpractice are the exception rather than the rule. When these problems are endemic, as they are in Indonesia, mechanisms that seek to monitor and penalise officials’ misbehaviour may be of little use. The problem is that other individuals within the same system need to take firm action against those found to be corrupt, but such individuals are themselves likely to be (or, at least, to have been) involved in malfeasance.35This is evident in the failure to

pro-vide most of the new agencies with sufficient resources or powers for them to be able to function effectively and, for example, in the failure of former president Megawati to take any action against her attorney general, who was found to have failed to report all of his assets, and whose wealth far exceeded what he could have been expected to save on the basis of his official remuneration.36 Having

said that, by mid-2005 it was clear that the new government was taking the anti-corruption effort much more seriously than its predecessor (McLeod 2005a: 152–3), though it was too soon to know how effective its efforts would be.

In short, the various recent reform efforts seem unlikely to succeed in bringing the performance of the civil service close to its full potential, because they fail to deal with the underlying combined problems of grossly defective personnel man-agement practices and unrealistically low basic salaries at the higher echelons. Worse still, the focus on these other approaches lulls all concerned into thinking that something important and useful is being done about reform, which merely serves to postpone the day when an Indonesian government will face up to the real issues. In this sense, misguided attempts at reform may be worse than none at all.37

The foregoing argument has suggested that the process of reform must be driven from the top down. Since it begins with the president, the question of who holds that office is crucial to Indonesia’s prospects for reform and recovery. Pres-ident Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono has already shown a much stronger interest in reform than his predecessor did, but his efforts to date have been too narrowly

38 ‘Megawati: Expel Corrupt Party Members’, Laksamana.Net, 7/4/2003; ‘Megawati

Laments Spread of Corruption to Legislature’, Jakarta Post, 20/5/2003.

focused on anti-corruption measures to be able to achieve the desirable objective of greatly improved performance on the part of the bureaucracy, the judiciary and the state-owned enterprises.

CONCLUSION

If Indonesia’s government is to be made effective in the sense in which that term has been used here—that is, if Indonesia is to return to sustained rapid economic growth—it is essential that discussion of the obvious need for reform of the civil service moves beyond platitudes (see, for example, Rais 2003) and presidential exhortations and lamentations38to meaningful analysis and concrete suggestions

as to the nature and implementation of such reform. The key is the creation of a competitive environment within the civil service through the provision of strong positive and negative incentives for good performance by its employees. Enhanced productivity of the bureaucracy and judiciary will materialise if the individuals that comprise them find this to be in their own interests.

In trying to predict the likely pace of change it is well to appreciate that such reforms will be resisted by the individuals whose present behaviour is at the heart of the problem (Robison and Hadiz 2004), and that they are also likely to be opposed by well-meaning people who believe corruption, collusion and nepo-tism can be made to go away by other means. Reform progress is therefore likely to be slow. Accordingly, the economy is unlikely to achieve its full potential for sustained, rapid economic growth for quite some time.

REFERENCES

ADB (Asian Development Bank) (2004), Country Governance Assessment Report, Republic of Indonesia, Manila <http://www.adb.org/Documents/Reports/CGA/ino.asp>. Anwar, Dewi Fortuna (2001), ‘Indonesia’s Transition to Democracy: Challenges and

Prospects’, in Kingsbury, Damien, and Budiman, Arief (eds), Indonesia: The Uncertain Transition, Crawford House, Adelaide: 3–16.

Callick, Rowan (2002a), ‘Mining Treasure Island’,Australian Financial Review, 15 May. Callick, Rowan (2002b), ‘Rio Mine Sale Revived’, Australian Financial Review, 4 November. Cameron, Lisa (1999), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic

Studies35 (1): 3–41.

Cole, David C., and Slade, Betty F. (1998), ‘Why Has Indonesia’s Financial Crisis Been So Bad?’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies34 (2): 61–6.

Crouch, Harold (1991), ‘Military–Civilian Relations in Indonesia in the Late Soeharto Era’, in Selochan, Viberto (ed.), The Military, State and Development in Asia and the Pacific, Westview Press, Boulder CO: 51–66.

Deuster, Paul (2002), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 38 (1): 5–37.

Dodd, Tim (2001), ‘East Kalimantan Sues Coal Mine for $1.5bn’, Australian Financial Review, 19 October .

Dodd, Tim (2003), ‘Sale of Borneo Coal Mine Stake Stalls’, Australian Financial Review, 10 February.

Donnan, Shawn (2004), ‘Lonely Voice Warns of New Robber Baron Mentality’, Financial Times, 24 May.

Elson, R.E. (2001), Suharto: A Political Biography, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Fane, George (2000), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’,Bulletin of Indonesian Economic

Stud-ies 36 (1): 13–44.

Fane, George (2003), ‘Change and Continuity in Indonesia’s New Fiscal Decentralisation Arrangements’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 39 (2): 159–76.

Filmer, Deon, and Lindauer, David L. (2001), ‘Does Indonesia Have a “Low Pay” Civil Ser-vice?’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 37 (2): 189–205.

Kadga, Shoeb (2004), ‘Jakarta Hitting the Right Notes’, Business Times Singapore, 30 November.

Kuncoro, Ari (2004), Bribery in Indonesia: Some Evidence from Micro-level Data’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 40 (3): 329–54.

Liddle, R. William (1985), ‘Suharto’s Indonesia: Personal Rule and Political Institutions’,

Pacific Affairs 58 (1), Spring: 68–90; reprinted in Liddle, R. William (1996), Leadership and Culture in Indonesian Politics, Asian Studies Association of Australia and Allen & Unwin, Sydney: 15–36.

Liddle, R. William (2003), ‘Indonesia’s Army Remains a Closed Corporate Group’, Jakarta Post,June 3.

Lindsey, Tim (2001), ‘Abdurrahman, the Supreme Court and Corruption: Viruses, Trans-plants and the Body Politic in Indonesia’, in Kingsbury, Damien, and Budiman, Arief (eds), Indonesia: The Uncertain Transition, Crawford House, Adelaide: 43–67.

Lingga, Vincent (2002), ‘Unshackling Imports from Corrupt Customs’, Jakarta Post, 5 February.

Mackie, J.A.C. (1970), ‘The Commission of Four Report on Corruption’, Bulletin of Indo-nesian Economic Studies 6 (3): 87–101.

McDougall, Walter A. (2003), ‘What the U.S. Needs to Promote in Iraq (Hint: It’s Not Democratization Per Se)’, Wire 11 (2), May, Foreign Policy Research Institute; available at <http://www.fpri.org/fpriwire/>.

McLeod, Ross H. (2000), ‘Government–Business Relations in Soeharto’s Indonesia’, in Peter Drysdale (ed.), Reform and Recovery in East Asia: The Role of the State and Economic Enterprise, Routledge, London and New York: 146–68.

McLeod, Ross H. (2005a), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’,Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 41 (2): 133–57.

McLeod, Ross H. (2005b), ‘The Economy: High Growth Remains Elusive’, in Reso-sudarmo, Budy P. (ed.), The Politics and Economics of Indonesia’s Natural Resources, Indo-nesia Update Series, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore: 31–50.

Mubyarto (1984), ‘Social and Economic Justice’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 20 (3): 36–54.

O’Driscoll, Gerald P., Jr., and Hoskins, Lee (2003), ‘Property Rights: The Key to Economic Development’, Policy Analysis, No. 482, 7 August: 1–17; available at <http://www.cato.org/pubs/pas/pa482.pdf>.

Pangestu, Mari, and Goeltom, Miranda Swaray (2001), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’,

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 37 (2): 141–71.

Rais, M. Amien (2003), ‘Crank Up the Engine Indonesia, We May Win the Race’, Jakarta Post, 9 May.

Ravallion, Martin (1988), ‘Inpres and Inequality: A Distributional Perspective on the Cen-tre’s Regional Disbursements’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 24 (3): 53–71. Resosudarmo, Budy P. (ed.) (2005), The Politics and Economics of Indonesia’s Natural

Resources, Indonesia Update Series, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore. Robison, Richard, and Hadiz, Vedi R. (2004), Reorganising Power in Indonesia: The Politics of

Oligarchy in an Age of Markets, RoutledgeCurzon, London and New York.

Roll, Richard and John Talbott (2003), Political and Economic Freedoms and Prosperity, Anderson School, University of California, Los Angeles, 19 June: 15–16; available at <http://www.anderson.ucla.edu/documents/areas/fac/finance/19-01.pdf>.

Sherlock, Stephen (2002), ‘Combating Corruption in Indonesia? The Ombudsman and the Assets Auditing Commission’,Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 38 (3): 367–83. Sherlock, Stephen (2003), Struggling to Change: The Indonesian Parliament in an Era of

Reformasi, Centre for Democratic Institutions, Canberra; available at <http://www.cdi.anu.edu.au/indonesia/indonesia_downloads/DPRResearchRe-port_S.Sherlock.pdf>.

Simanjuntak, Tertiani Z.B. (2002), ‘Most Judges Fail to Clarify Their Wealth: KPKPN’,

Jakarta Post, 22 July.

Soesastro, Hadi, and Atje, Raymond (2005), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’,Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 41 (1): 5–34.

Taufiqurrahman, M. (2003), ‘Semen Padang Conflict Drags On, Despite New Manage-ment’, Jakarta Post, 21 May.

Weiss, Stanley A. (2002), ‘Send the Military to Business School’, International Herald Tri-bune, 19 September.

Witular, Rendi A. (2005), ‘Govt to Fire Corrupt Bureaucrats’, Jakarta Post, 3 May.

World Bank (2005), Indonesia: New Directions, World Bank Brief for the Consultative Group on Indonesia, 19–20 January.