Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 20:57

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

The Influence of Student Perceived Professors’

“Hotness” on Expertise, Motivation, Learning

Outcomes, and Course Satisfaction

Jeanny Liu , Jing Hu & Omid Furutan

To cite this article: Jeanny Liu , Jing Hu & Omid Furutan (2013) The Influence of

Student Perceived Professors’ “Hotness” on Expertise, Motivation, Learning Outcomes, and Course Satisfaction, Journal of Education for Business, 88:2, 94-100, DOI:

10.1080/08832323.2011.652695

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2011.652695

Published online: 04 Dec 2012.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 901

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.652695

The Influence of Student Perceived Professors’

“Hotness” on Expertise, Motivation, Learning

Outcomes, and Course Satisfaction

Jeanny Liu

University of La Verne, La Verne, California, USA

Jing Hu

California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, California, USA

Omid Furutan

University of La Verne, La Verne, California, USA

Recent research has indicated a noticeable increase in students who rate their professors as either “hot” or “not” on RateMyProfessors.com. The authors further explored this issue by examining the influence of professors’ perceived hotness in the classroom. Results indicate that when professors are perceived to be high in attractiveness, students view these professors as having more expertise. Furthermore, students are more motivated to learn, perceive that they learn better, are more satisfied, and give higher teaching evaluations. Additionally, there appears to be an interaction between the gender of the student and the influence of attractiveness; levels of attractiveness appear to affect female students more than male students.

Keywords: hotness, motivation to learn, physical attractiveness, student evaluations

In this era of Internet reliance, students have increased their use of unconventional rating scales that are outside of a typ-ical student teacher evaluation form as an evaluative compo-nent in searching for prospective professors. Typically, a stan-dardized teaching evaluation form would be a good source to understand professors’ teaching effectiveness. However, students are turning to the Internet for information and a number of websites have emerged where students can review course experiences and rate professors. Computer-mediated word-of-mouth sites, such as RateMyProfessors.com and PickAProf.com, are largely used by students to gather and shop for information about prospective professors (Hossain, 2010). These sites are widely used and serve as an informa-tion hub by students in their selecinforma-tion of future courses and in-structors. One popular website, RateMyProfessors.com, of-fers students the opportunity to anonymously quantify and post perceptions of their professors based on five rating

Correspondence should be addressed to Jeanny Liu, University of La Verne, Department of Marketing and Law, 1950 3rd Street, La Verne, CA 91750, USA. E-mail: jeanny.liu@laverne.edu

factors: easiness, hotness, helpfulness, clarity, and interest level. While instructors’ certain personality dimensions have demonstrated an influence in student evaluations, research investigating professors’ hotness or physical attractiveness has been limited. Additionally, there is limited research on the actual usefulness of the hotness rating of professors. Pro-fessors’ hotness has been shown to impact student evaluation of them (Felton, Koper, Mitchell, & Stinson, 2008). Thus, as students continue to evaluate their professors through these sites, these new ratings of teaching evaluation raises the ques-tion of how useful hotness is as a crowd sourced rating at-tribute in predicting teacher performance, teacher’s ability to motivate and the learning experience, for a prospective student. Since the inception of RateMyProfessors.com, there has been limited research investigating the use of a hotness measure in evaluating teaching effectiveness. Several stud-ies examined at teachers’ hotness and its impact on student teacher evaluations. These studies have found teachers’ hot-ness to be associated with more positive affect and more pos-itive student evaluation of attractive teachers (Felton et al.; Hamermesh & Parker, 2005; Hossain; Riniolo, Johnson, Sherman, & Misso, 2006). In several of these studies, the

STUDENT PERCEPTION OF PROFESSORS’ HOTNESS 95

results indicate that attractive teachers also demonstrated a substantial positive impact on instructional productivity (Felton et al.; Hamermesh & Parker).

Results from these studies raised some particularly inter-esting questions. Other than the positive impact on student evaluations, do attractive or hot professors also impact the student learning experience? If so, how does it influence their learning experience? What are some positive (or negative) outcomes that might be associated with attractive profes-sors? To what extent do attractive professors influence stu-dents’ perception of their learning experience? The present study attempts to investigate the effect of student-perceived instructors’ hotness and students’ perception of their own learning, motivation, and course satisfaction. Specifically, we attempted to investigate this assumption in a higher edu-cation environment examining both undergraduate and grad-uate students to examine the potential impact, either positive or negative, stemming from professors’ attractiveness.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Defining Hotness

It is becoming increasingly popular to evaluate professors based on their hotness (Felton et al., 2008; Hossain, 2010; Riniolo et al., 2006). However, the meaning of this construct is still unclear. Existing literature has defined hotness in var-ious ways, such as physical attractiveness (Bonds-Raacke & Raacke, 2007; Riniolo et al., 2006; Silva et al., 2008), sexi-ness (Felton et al., 2008; Felton, Mitchell, & Stinson, 2004), or good looks (Hamermesh & Parker, 2005). Hotness, despite its description, remains a subjective measure and can be in-terpreted differently by individuals. This may account for the seemingly random chili peppers (assigned indicators of hotness) on evaluations posted on RateMyProfessors.com. In this article, hotness is defined as a student’s subjective perception of a professor’s physical features. Aspects of this perception are further explored using student feedback later in the study. We expect that students would have varying per-ceived levels of hotness for the same instructor and that the overall level of hotness would take into consideration various aspects of the hotness perceptions from students.

Physical Attractiveness, Expertise, and Motivation

The influence of physical attractiveness in education is not new. Prevalent literature documents that attractive-looking students are often judged more positively than unattractive students. Students’ physical attributes have been considered to influence teachers’ behaviors and attitudes toward good-looking students. This influence exists in teachers’ impres-sion formations and judgment of students (Ritts, Patterson, & Tubb, 1992). This is also a factor in teachers’ judgment of students’ intelligence and academic competence (Adams, 1978; Ross & Salvia, 1975); in the frequency of

teacher-student interactions (Adams & Cohen, 1974; Algozzine, 1977); and in teachers’ expectations (Clifford & Walster, 1973). Adams and Cohen (1974) demonstrated that teachers utilize a beauty-is-good stereotype in students, as their study discovered that attractive looking students are a salient factor in the frequency of teacher-student interactions. Studies have also found that children consistently choose playmates based on facial appearances, favoring attractive over unattractive individuals (Adams & Crane, 1980). Physical attractiveness has further been demonstrated to influence parents’ attitudes on the choice of peers for their children (Adams & Crane) and their attitudes toward their own infants (Stephan & Langois, 1984). The influence of physical attractiveness has generated much attention from researchers in the past, and there is a great amount of literature and history on this stereotype both in educational and social contexts.

Friedrich Schiller defined beauty as being both “physical and spiritual” (Hohr, 2002, p. 64); the two aspects act as powers complementing, supporting, and yet simultaneously depending on each other. Hohr argued that attractiveness is a response to the growing phenomenon of “socio-economic complexity, differentiation and social disintegration” (p. 59). This growing awareness gives physically attractive commu-nicators certain advantages as demonstrated in social psy-chology literature. In the workplace, physical attractiveness is prominent in receiving benefits such as higher job evalu-ations (Dipboye, Arvey, & Terpstra, 1977). In the commu-nication literature, attractive communicators are found to be more persuasive, treated better in social settings, and achieve greater career success (Langlois et al., 2000). Additionally, Joseph (1982) indicated that physically attractive models are liked more, perceived more favorably, and have a positive impact on the products with which they are associated in the advertising industry. Here we summarize the effects of phys-ically attractive communicators and concludes that attractive sources consistently are perceived more favorably and as-signed more positive qualities. Consequently, it was reason-able for us to hypothesize that hot professors would be more likely to generate favorable feelings among students and per-ceived with more expertise, and students would be motivated to learn under the influence of such favorable feelings.

Hypothesis 1(H1):Students would perceive hot professors to have more expertise.

H2: Students would be more motivated to learn by a hot professor.

Physical Attractiveness, Instructional

Productivity, and Immediacy in the Classroom

Professors’ physical attractiveness has been demonstrated to have an impact on student-teacher evaluation and immedi-acy in the classroom. Greater immediimmedi-acy, in turn, has been shown to lead to higher student motivation and better stu-dent learning experience. Riniolo et al. (2006) found that professors who were perceived as attractive consistently re-ceived higher student evaluations when compared with the

unattractive group. Those who are perceived as physically at-tractive receive about 0.8 of a point higher on a 5-point evalu-ation. The research suggests that attractive instructors trigger positive responses by the students and receive positive bene-fits in student evaluations. If students perceive their teachers as more physically attractive, they would have more gen-erally positive feelings toward the teacher and consequently have an increased desire to give higher ratings on evaluations. A study by Hamermesh and Parker (2005) found the same positive relationship between teachers’ facial beauty and in-structional ratings by undergraduate students. Students’ high evaluation of the teacher can be partially explained by their high immediacy to the teacher as the immediacy level in-creases when students have physically attractive professors (McCroskey, Sallinen, Fayer, Richamond, & Barraclough, 1996; Rocca & McCroskey, 1999).

The construct of immediacy has received much attention by the communication scholars since 1970s. The construct was first defined as the perceived distance between people, where positive affect enhances closeness or immediacy be-tween them (Mehrabian, 1971). Research has pointed to the importance of teachers’ immediacy in the classroom and that it increases student interactions with the teacher and en-courages reciprocity responses in students (Gouldner, 1960). Within the work of immediacy, teachers’ nonverbal imme-diacy behaviors have been associated with student-teacher evaluations (McCroskey, Richmond, Sallinen, Fayer, & Barraclough, 1995) and perceived cognitive learning (McCroskey & Richmond, 1992). Examples of nonverbal be-haviors include eye contact, voices, facial expressions, body movement and position, and gestures while talking in class (Richmond, Gorham, & McCroskey, 1987). This research suggests that teachers across all discipline must pay atten-tion to their nonverbal behaviors in class and to develop the communication skills necessary in order to build positive immediacy and to enhance instructional productivity.

The relationship between teachers’ hotness and how their students learn is not clear. However, physical attraction has been documented as a contributing factor for immediacy (Rocca & McCroskey, 1999), and teachers who are thought as more immediate are also more effective in encourag-ing (Comstock, Rowell, & Bowers, 1995) and motivatencourag-ing (Christophel, 1990) student learning. Therefore, we believe that physically attractive teachers have a positive effect on student learning and students are more satisfied with their class because of the immediacy that the attractiveness creates.

H3: Students would be more satisfied with the class, have better learning outcomes, and give better instructor eval-uations when having a hot professor.

METHODOLOGY

We conducted an empirical study in order to find out: what is hotness in students’ minds, and what is the relationship

between hotness and students’ motivation to learn, learning outcomes, satisfaction, and instructor evaluation. In the initial stage of the study, a small group of students were asked to define hotness using six words. A content analysis of students’ responses revealed five dimensions in the meaning of hotness. These five dimensions were used to create a scale of hotness for the main study. In the main study, the hotness scale was incorporated into a student survey to examine its relationship with student learning. This survey was then given to a larger sample.

Sample

A survey was conducted with business students at a pri-vate university located in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. These students were asked about their perceptions of their professors, their learning outcomes, as well as their personal profiles. By using a cluster-sampling procedure, we created a sample frame consisting of a list of graduate and undergrad-uate classes. From the list, students from 12 business classes volunteered to participate in the survey, resulting in a total of 207 survey participants. Those that did not respond were ignored since the rate was less than two percent (Miller & Smith, 1983).

The participants in the study were almost evenly divided by gender (55.8% men). It should be noted that female par-ticipation in the study was much higher than the national average for business school enrollment, but was consistent with the gender profile of the private university in the study. This study included graduate and undergraduate students (63.1% undergraduate) and a relatively large ratio of Hispanic and Asian participation when compared with the rest of the country (24.4% Caucasian, 29.5% Hispanic, 5.5% African American, 30% Asian).

Study Design

To compare the effectiveness of a professor with a high hot-ness score versus a professor with a low hothot-ness score, we chose a different approach from the popular professor rat-ing websites, which have the students rate their professors at the end of a course. In this study, we used the critical inci-dent technique. A situation was described to stuinci-dents first. Students were then asked to think of a professor (either hot or not) that would fit in this situation and answer questions about this professor. The situation included two parts. In the first part, students were given the following scenario:

Imagine that you are invited to post a review of your profes-sors on RateMyProfessor.com relevant to a few dimensions, such as hotness, easiness, helpfulness, and clarity. Think of a class you had in the past 3 years with a professor with whom you would rate high in hotness (with a red chili pepper). Think about the class he/she was teaching and answer the following questions.

STUDENT PERCEPTION OF PROFESSORS’ HOTNESS 97

The participants then answered questions about the gender of the professor, their perceptions of the hotness of the profes-sor, the expertise of the profesprofes-sor, their motivation to learn, and their satisfaction with the course. The students were also asked about learning outcomes and asked to evaluate their professor. In the second part of the survey, students were asked the same set of questions, but in reference to a profes-sor for whom they would rate low in hotness.

Instrumentation

To test the hypotheses, six key measurements were employed in the main survey, including hotness, expertise, motivation to learn, satisfaction, learning outcome, and instructor rating. The hotness measure was developed in the initial stage of this study using content analysis of a student survey, as there was no existing scale to measure hotness. Other measures were borrowed from established scales for better validity and reli-ability and then modified slightly to fit in the circumstances of this study.

Hotness. To create a scale to measure hotness, in the initial stage of the study we asked students what the word hotnessmeant in the context of evaluating professors. Stu-dents were asked to take a moment to write down six words that they might associate with the word hotness. Forty stu-dents participated in this study. Five dimensions of hotness emerged after a content analysis of students’ responses: good looks, good figure, well dressed, attractive, and sexy. These five dimensions were then used to measure hotness in the main study. Reliability was tested using Cronbach’s alpha in SPSS, version 17. This scale appeared reliable (Cronbach’s

α =.905). All the measurements used the 5-point

Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Expertise. Expertise was a modified scale from Oha-nian (1990) to fit in this study. These items included “the instructor seemed like an expert,” “the instructor seemed experienced,” “the instructor seemed knowledgeable,” “the instructor seemed qualified,” and “the instructor seemed skilled” (Cronbach’sα=.820).

Motivation to learn. Questionnaire items measuring motivation to learn were derived from a scale in the peda-gogical study by Ackerman and Hu (2009). This measure

contained items such as “I was very motivated to learn the material associated with this class,” “I thoroughly read every assigned chapter in this class,” and “Relative to other classes I have taken, I worked more in this class” (Cronbach’sα=

.743).

Satisfaction. This measure was derived from Oliver’s (1980) scale on satisfaction. The scale included three items: “I was satisfied with my experience in this class,” “I believe I did the right thing when I took this class,” and “Overall, I am satisfied with the decision to take this class” (α=.912).

Learning outcome. The measure of perceived learning outcome has five items. It was a modified scale from Bamber and Castka (2006). The items included “I think the course has been very important for me,” “Overall, I think the course was excellent,” “Overall, I think the course content was very interesting,” “Overall, I found the course material to be very useful,” and “I feel I retained what I have learned in this class, even after the end of the semester” (Cronbach’sα=.898).

Instructor evaluation. This scale came from Serva and Fuller (2004) and included three items “I was satisfied with this instructor,” “I learned a lot from this instructor,” and “I would love to take another course with this instructor again” (Cronbach’sα=.904).

ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

Manipulation Check

The five-item hotness measure served as a manipulation check in this study. The results showed that the manipu-lation of the two conditions was successful. When asked to think of a professor high in hotness, students gave higher values on the hotness measure than they did when they were asked to think of a professor low in hotness (Mhigh=3.40, Mlow=1.94)=16.942,p<.001.

Results

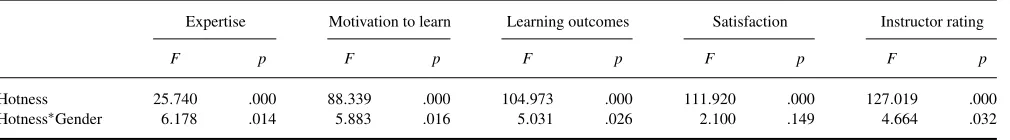

Because each student was asked to give responses to both scenarios, a repeated measures analysis of variance was suit-able for the analysis. The results revealed that students did react to a professor high in hotness and low in hotness differ-ently (see Table 1). When having professors high in hotness,

TABLE 1

Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance Results

Expertise Motivation to learn Learning outcomes Satisfaction Instructor rating

F p F p F p F p F p

Hotness 25.740 .000 88.339 .000 104.973 .000 111.920 .000 127.019 .000

Hotness∗Gender 6.178 .014 5.883 .016 5.031 .026 2.100 .149 4.664 .032

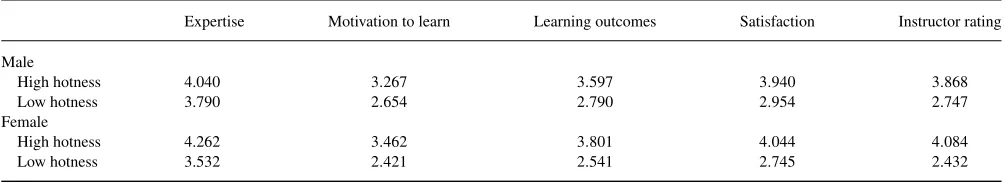

TABLE 2

Means of Perceptions of Female Versus Male Students

Expertise Motivation to learn Learning outcomes Satisfaction Instructor rating

Male

High hotness 4.040 3.267 3.597 3.940 3.868

Low hotness 3.790 2.654 2.790 2.954 2.747

Female

High hotness 4.262 3.462 3.801 4.044 4.084

Low hotness 3.532 2.421 2.541 2.745 2.432

the students viewed the professors as having more expertise, F(1, 205)=25.740,p<.001. The students were more

moti-vated to learn,F(1, 205)=88.339,p<.001; perceived they

learned better,F(1, 205)=104.973,p<.001; were also more

satisfied with their class,F(1, 205)=111.920,p<.001; and

gave their professors higher ratings, F(1, 205)=127.019, p<.001. Thus, all three hypotheses were supported.

The effect of perceived hotness of professors differed be-tween the genders of students. There was an interaction effect between the hotness of professors and genders of students. Levels of hotness appeared to affect female students more than male students (see Table 2). Compared with male stu-dents, female students perceived hot professors to have higher expertise,F(1, 205)=6.178,p=.014. With hot professors, female students, compared with male students, were more motivated to learn,F(1, 205)=5.883,p=.016, perceived they learned better,F(1, 205)=5.031,p=.026, and gave these professors higher ratings,F(1, 205)=4.664,p=.032. Although this interaction effect was not significant on the satisfaction variable, the mean perception of female students versus male students showed the same tendency (see Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this research was to examine professors’ physical attractiveness and its relationship to students’ own evaluation of their behavior and learning outcomes. One of the assumptions made in this study was that the physical appearances of teachers can potentially affect instructional productivity. Specifically by having an attractive appearance, teachers can provide more opportunities for student inter-action and make learning more enjoyable. Results in the data support the idea that students consider themselves to be more motivated and learned more when they had an attractive professor. These results confirmed our assumption and that professors’ attractiveness can contribute in important ways toward increasing a teacher’s effectiveness. Nevertheless, ad-ditional research can be done to clarify the effects of different levels of attractiveness on student learning and the perception of attractiveness across time.

It was found that as perceived teachers’ attractiveness in-creased, students’ satisfaction in course also increased. It

would appear that attractive teachers contribute to teachers receiving higher student evaluations. This finding reinforces the prior research (Felton et al., 2008; Felton et al., 2004; Riniolo et al., 2006), which acknowledged the positive im-pact of attractive instructors on student evaluations. Our study extends previous research on the impact of teachers’ attrac-tiveness by suggesting that teachers’ appearances play an important role on student perceptions and learning experi-ences in the classroom. Specifically, physical attractiveness may generate a positive effect in student perception. Our re-sults are also consistent with Rocca and McCroskey’s (1999) findings that attractiveness increases immediacy and greater immediacy benefits the learning experience.

This result has implications for teachers, administrators, and faculty looking for ways to improve student learning. An important implication of this study for teachers is if per-ceived attractiveness can increase students’ motivation to learn should a teacher go out of their way to look attractive? To what extend should a teacher go out of their way to look attractive? While teachers may be the catalyst between stu-dents and the subject matter, are attractive teachers capable of stimulating any subject matter? While our study indicates a relationship between professors’ attractiveness and students’ own learning evaluations, it did not measure students’ moti-vation level toward a particular subject matter. Nevertheless, our findings provide preliminary support that teachers’ phys-ical appearance and student learning outcomes are in fact significantly correlated.

One interesting result from the study uncovered a gender difference in the effect of professors’ perceived attractive-ness between female and male students. The results suggest that female students, when compared to male students, per-ceived attractive professors as having higher expertise (Ms= 4.26 vs. 4.04, )F(1, 205)=6.178,p=.014; were more mo-tivated to learn (Ms=3.46 vs. 3.28,F(1, 205)=5.883,p= .016; perceived they learned better (Ms=3.80 vs. 3.60,F(1, 205) =5.031,p =.026; and gave these professors higher ratings (Ms=4.08 vs. 3.87,F(1, 205)=4.664,p=.032. The level of hotness appeared to influence female students more than male students.

This leads to an interesting question: Is the perception of physical attractiveness more salient for women than for men? Social psychological research has somewhat supported the

STUDENT PERCEPTION OF PROFESSORS’ HOTNESS 99

claim that physical attractiveness has greater consequences for women’s self-esteem and life chances (Jackson, 1992). The beauty ideal as seen in media demonstrates that thinness in women continues to be highly valued, more by women than men (Sypeck et al., 2006). Hill (2002) also indicated that skin color has influenced assessment of physical attrac-tiveness differently between genders and that the association is significantly weaker for men. Such findings are consistent with our study that physical attractiveness affects assess-ment differently between men and women; it also explains the stronger effect observed on female students than male students.

There were some limitations with our study. First, our findings should be interpreted with some caution. The sur-vey for this study was done at a private university in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. It is not clear whether the findings can be fully generalizable as the sample represented students at a single university and in an area where physical appearances are valued. Students in private universities and in coastal metropolitan areas such as Los Angeles or New York may be more prone to fashion and therefore put greater emphasis on appearance or hotness of professors when eval-uating them. Thus, the hotness bias may be more apparent in these areas. However, our results on the relationship be-tween attractiveness and teaching evaluations are consistent with previous studies (Felton et al., 2008; Felton et al., 2004; Riniolo et al., 2006). It will be useful to further our study by confirming other findings, such as learning outcomes, mo-tivation, and perceived expertise, in nonmajor metropolitan areas and other types of universities.

A second limitation of this study was that the hotness measure could be further refined. Because there was no es-tablished scale ready for use, a more systematic scale de-velopment can be done to ensure its reliability, validity, and extensibility. For example, more caution should be used in selecting sample, more methods should be used to describe its meaning in addition to word association used here, the scale should be tested on a second sample to examine its consistency, and additional work needs be done to examine its validity. However, this study has laid the groundwork in developing a scale for instructor hotness.

Third, the effectiveness of teaching was measured based on student perception. Students’ expectations for themselves and their baseline used for comparison may be different, so their self-iterated learning outcomes may be different from real leaning outcomes, such as classroom performance and career development related to that course. As anonymity was required in the survey, there was no way for us to get this information. Real course performance could be included in the research design in the future for a more credible measure of learning effectiveness.

Furthermore, we inferred teaching competence by asking students for their perception of learning outcomes. Hence, we did not directly measure learning benefits. It would be interesting to see if there are actual learning benefits to

hotness or if the results are only perceived. An objective test, controlling for curriculum and teaching style, should be conducted between hot and nonhot teachers. Such an objec-tive test would not necessarily have to cover a real subject or be a long course.

CONCLUSION

Here we focused on examining the meaning of hotness and its impact on others, specifically, whether hot professors actually impact students’ learning. The research showed that hotness has multiple dimensions and significant influences on student learning, motivation to learn, and satisfaction. Overall, this research offers a good preliminary basis for further research on the effect of physical appearance on student learning. We also present a basis for additional testing for actual teaching effectiveness and the role that gender plays in the academic environment.

While a wide range of other factors demonstrate important implications for student learning, the present study presents additional insights into professor-student communication in the classroom. The principle of immediacy has been used in the field of communication to explain increased effort and communication effectiveness between individuals when attraction exists (Roger & Bhowmik, 1971), and also that attraction between individuals can increase the quantity of communication attempts (Rocca & McCroskey, 1999). It is important to note that a professor’s attractiveness can also play an important role in giving a professor greater oppor-tunities to engage students and increase the quantity of in-formation exchanged. In addition, a professor who is rated highly by students is more likely to exert influence on student behavior and to achieve better learning outcomes.

Despite the progression of society, individual stereotypes still exist that grant people with more or less credit based on their attractiveness. While having limitations, the present study validates the findings of previous literature on the in-fluence of physical attractiveness and sheds new light on outcomes that have not been previously addressed. Although we do not suggest that academic institutions should include hotness criteria as part of their recruiting strategy, we hope that the findings will help to increase awareness that efforts should also be made to maintain a professional physical ap-pearance in the classroom.

REFERENCES

Ackerman, D., & Hu, J. (2009, April).Effect of active learning on learning motivation and outcomes among marketing students with different learn-ing styles. Paper presented at the Marketing Education Association 2009 Conference, Newport Beach, CA.

Adams, G. R. (1978). Racial membership and physical attractiveness effects on preschool teachers’ expectations.Child Study Journal,8, 29–41. Adams, G. R., & Cohen, A. S. (1974). Children’s physical and interpersonal

characteristics that effect student-teacher interactions. The Journal of Experimental Education,43, 1–5.

Adams, G. R., & Crane, P. (1980). An assessment of parents’ and teachers’ expectations of preschool children’s social preference for attractive or unattractive children and adults.Child Development,5, 224–231. Algozzine, B., (1977). Perceived attractiveness and classroom interactions.

The Journal of Experimental Education,46, 63–66.

Bamber, D., & Castka, P. (2006). Personality, organizational orientations and self-reported learning outcomes.Journal of Workplace Learning,18, 73–92.

Bonds-Raacke, J., & Raacke, J. D. (2007). The relationship between physical attractiveness of professors and students’ ratings of professor quality.

Journal of Psychiatry, Psychology and Mental Health,1(2), 1–7. Christophel, D. M. (1990). The relationships among teacher immediacy

behaviors, student motivation, and learning.Communication Education,

37, 323–340.

Clifford, M. M., & Walster, E. (1973). The effect of physical attractiveness on teacher expectations.Sociology of Education,46, 248–258. Comstock, J., Rowell, D., & Bowers, J. W. (1995). Food for thought: Teacher

nonverbal immediacy, student learning and curvilinearity. Communica-tion EducaCommunica-tion,44, 251–266.

Dipboye, R. L., Arvey, R. D., & Terpstra, D. E. (1977). Effects of student’s race physical attractiveness, and dialect on teacher evaluations. Contem-porary Educational Psychology,3, 77–86.

Felton, J., Koper, P. T., Mitchell, J., & Stinson, M. (2008). Attractiveness, easiness and other issues: student evaluations of professors on Ratemypro-fessors.com.Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education,33, 45–61. Felton, J., Mitchell, J., & Stinson, M. (2004). Web-based student

evalua-tion of professors: The relaevalua-tions between perceived quality, easiness and sexiness.Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education,29, 91–108. Gouldner, A. W. (1960). A norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement.

American Sociological Review,26, 161–178.

Hamermesh, D. S., & Parker, A. M. (2005). Beauty in the classroom: In-structors’ pulchritude and putative pedagogical productivity.Economics of Education Review,24, 369–376.

Hill, M. E. (2002). Skin color and the perception of attractiveness among African Americans: Does gender make a difference?Social Psychology Quarterly,65, 77–91.

Hohr, H. (2002). Does beauty matter in education? Friedrich Schiller’s neo-humanistic approach.Journal of Curriculum Studies,34, 59–75. Hossain, T. M. (2010). Hot or not: An analysis of online professor-shopping

behavior of business students.Journal of Education for Business,85, 165–167.

Jackson, L. A. (1992).Physical appearance and gender: Sociobiological and sociocultural perspectives. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Joseph, W. B. (1982). The credibility of physically attractive communicators: A review.Journal of Advertising,11(3), 15–24.

Langlois, J. H., & Kalakanis, L., Rubenstein, A. J., Larson, A., Hallamm, M., & Smoot, M. (2000). Maxims or myths of beauty? A meta-analytic and theoretical review.Psychological Bulletin,126, 390–423.

McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (1992). Increasing teacher influence through immediacy. In V. P. Richamond & J. C. McCroskey (Eds.),Power

in the classroom: Communication, control, and concern(pp. 101–119). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

McCroskey, J. C., Richmond, V. P., Sallinen, A., Fayer, J. M., & Barraclough, R. A. (1995). A cross-cultural and multi-behavioral analysis of the relationship between nonverbal immediacy and teacher evaluation.

Communication Quarterly,44, 281–291.

McCroskey, J. C., Sallinen, A., Fayer, J. M., Richamond, V. P., & Barraclough, R. A. (1996). Nonverbal immediacy and cognitive learning: A cross-cultural investigation.Communication Education,45, 200–211. Mehrabian, A. (1971).Silent messages(vol. viii). Oxford, UK: Wadsworth. Miller, L. E., & Smith, K. L. (1983). Handling nonresponse issues.

Journal of Extension, 21(5). Retrieved from http://www.joe.org/joe/ 1983september/83–5-a7.pdf

Ohanian, R. (1990). Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractive-ness.Journal of Advertising,19(3), 39–52.

Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions.Journal of Marketing Research,17, 460–469. Richmond, V. P., Gorham, J. S., & McCroskey, J. C. (1987). The relationship

between selected immediacy behaviors and cognitive learning. In M. A. McLaughlin (Ed.),Communication yearbook 10(pp. 574–590). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Riniolo, T. C., Johnson, K. C., Sherman, T. R., & Misso, J. A. (2006). Hot or not: Do professors perceived as physically attractive receive higher student evaluations?The Journal of General Psychology,133, 19–34. Ritts, V., Patterson, M. L., & Tubbs, M. E. (1992). Expectations, impressions,

and judgments of physically attractive students: A review.Review of Educational Research,62, 413–426.

Rocca, K. A., & McCroskey, J. C. (1999). The interrelationship of student ratings of instructors’ immediacy, verbal aggressiveness, homophily, and interpersonal attraction.Communication Education,48, 308–316. Roger, E., & Bhowmik, D. (1971). Homophily-heterophily: Relational

concepts for communication research. Public Opinion Quarterly, 34, 523–538.

Ross, M., & Salvia, J. (1975). Attractiveness as a biasing factor in teacher judgments.American Journal of Mental Deficiency,80, 96–98. Serva, M. A., & Fuller, M. A. (2004). Aligning what we do and what we

measure in business schools: Incorporating active learning and effective media use in the assessment of instruction.Journal of Management Edu-cation,28, 19–38.

Silva, K. M., Silva, F. J., Quinn, M. A., Draper, J. N., Cover, K. R., & Munoff, A. (2008). Rate my professor: Online evaluations of psychology instructors.Teaching of Psychology,35, 71–80.

Stephan, C. W., & Langlois, J. H. (1984). Baby beautiful: Adult attribu-tions of infant competence as a function of infant attractiveness.Child Development,55, 576–585.

Sypeck, M. F., Gray, J. J., Etu, S. F., Ahrens, A. H., Mosimann, J. E., & Wiseman, C. V. (2006). Cultural representations of thinness in women, redux: Playboy magazine’s depiction of beauty from 1979 to 1999.Body Image,3, 229–235.