Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji], [UNIVERSITAS MARITIM RAJA ALI HAJI

TANJUNGPINANG, KEPULAUAN RIAU] Date: 13 January 2016, At: 17:30

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

A Longitudinal Study of Total Quality Management

Processes in Business Colleges

Gary Vazzana , John Elfrink & Duane P. Bachmann

To cite this article: Gary Vazzana , John Elfrink & Duane P. Bachmann (2000) A Longitudinal Study of Total Quality Management Processes in Business Colleges, Journal of Education for Business, 76:2, 69-74, DOI: 10.1080/08832320009599955

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320009599955

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 46

View related articles

A

Longitudinal Study of Total

Quality Management Processes in

Business Colleges

GARY VAZZANA

JOHN ELFRINK

DUANE P. BACHMANN

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Central Missouri State University

Warrensburg, Missouriur purpose in

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

this study was to0

assess the use of quality processes in higher education institutions (HEI), particularly in the academic business schools or units of those institutions. Our research involved a longitudinal, empirical investigation that identified the types of issues on which quality processes are used, the techniques used to implement quality improvements, and if and how use has changed over a 3-year period.Total quality management (TQM) processes have made their way into HEIs in the United States and other countries. Although the term TQM is universally recognized, educational institutions are applying quality process- es under a variety of similar names. Those include total quality (TQ), total quality education (TQE), and continu-

ous quality improvement (CQI) (Buch &

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Shelnutt, 1995; Entin, 1993; Gilbert, Keck, & Simpson, 1993; Mullin & Wil- son, 1995). Currently the AACSB (Inter- national Association of Management Education) subsumes the use of quality processes under the CPI (continuous process improvement) label. Success in industry and a growing need to improve the value of higher education for its stakeholders have encouraged the adop- tion of these processes (Elmuti, Kathawala, & Manippallili, 1996).

In our study, we investigated the

ABSTRACT. In this article, we

assess the use of total quality manage- ment processes and identify trends in their adoption at colleges in the Unit- ed States. A survey distributed to busi- ness deans in 1995 and 1998 was used to gather information concerning changes in the use of TQM. Mission development, strategy determination, and the setting of goals increased dur- ing the survey period. The use of advi- sory boards and cross-functional teams also increased. Few colleges are

using TQM successfully to manage the core learning process; neverthe- less, overall use of TQM compared

favorably with its use in business.

issues propelling the use of quality processes, focusing on assessment of the teaching and learning process and the controversy surrounding applica- tion of TQM-type concepts in the aca- demic environment. We also discuss how quality processes are being applied in HEIs, and finally, the results of two surveys of more that 400 heads of aca- demic business units (deans or depart- ment chairpersons).

Assessment as an Impetus

to Change

There are several reasons why assess- ment of the teaching and learning process has spurred the use of quality processes in the United States. Many states are being influenced by their con-

stituencies to improve the quality of edu- cation, from grammar school through the postsecondary level. States are request- ing or mandating that student learning be assessed to demonstrate the quality of their education. The workhorse of this assessment is the use of standardized multiple-choice tests, with centralized predetermination of which learning out- comes should be assessed (Hoachlander, 1998). Student learning and assessment have also become a top priority of busi-

ness schools. In a 1999 Newsline

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

survey of AACSB member schools, businessdeans selected teaching effectiveness, outcome assessment, and managing external relationships as the issues most critical to business education.

Another impetus for the use of quali- ty processes, especially in the teaching/ learning process of HEIs, is the similari- ty of the paradigms of assessment-as-

learning

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(AAL)

and TQM (American Association of Higher Education, 1992).Both include a focus on quality, empow- erment of faculty and students, involve- ment of constituencies, continuous improvement of the learning process, development and use of learning out- comedcriteria, and systematic, scientific measurement of learning results, with regard to the institution and the educator (Mullin & Wilson, 1995; Vazzana, Win- ter, & Waner, 1997).

An emphasis on a decentralized

November/Decernber 2000 69

approach to teachingllearning can help administrators side-step the centralized inspection approach of states and the federal government. Quality processes that emphasize closeness to the cus- tomer are a foundation of a decentral- ized assessment approach, whose aim is to produce teaching and learning improvements specifically tailored to

the needs of each HEI’s constituencies.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

TQM-Type Quality Processes in Business

Several questions should be addressed when discussing the use of quality processes in educational institu- tions. Have these processes been suc- cessful in business? Are they cost effi- cient? Can they be applied to the teaching/learning process?

Firms that have actively pursued the Malcolm Baldrige Award for quality (33 states have their own Malcolm Baldrige- type award) believe that there was an overwhelming improvement in their

company’s performance (Bergquist

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

&Ramsing, 1999). Performance improve- ments took an average of at least 2.5 years to be realized after adoption of

TQM. According to the U.S. Commerce

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Department, Baldridge award winnershad triple the increase in shareholder’s value compared with the Standard and Poor’s 500 (Tai & Przasnyski, 1999).

It would be difficult to argue that the use of various quality processes would not be useful in the management of organizations. Nevertheless, data show that only 20% to 30% of organizations adopting TQM have thrived (Becker, 1993: Brigham, 1993). Some companies have failed because the costs of quality were too high as a result of an obsession over the process (Brigham, 1993). In addition to costs, cumbersome bureau- cracies, slow deployment, unsupportive leadership imposing TQM from above, and lack of training and rewards appear to be major causes of failure (Becker, 1993; Mathew & Katel, 1992).

The Quality Movement in Higher Education

It became clear in the 1980s that global competition, the needs of a high-

tech information society, corporate

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

70

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Journal of Education for Businessdownsizing, and re-engineering had brought about the need for a new type of workforce. Such a workforce would have to be able to adapt itself continual- ly to meet the needs of an ever-more complex and changing environment.

A milestone study commissioned by the American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of Business (Porter & McKib- bin, 1988) elucidated the challenges to business and higher education in devel- oping the new work force. The authors pointed out that graduates must be able to integrate problem solving and deci- sionmaking across disciplines, be able to communicate expertly, be able to work in teams, and be capable of relearning to meet challenges posed by the continuing metamorphism of their environment. Porter and McKibbin’s study found the development and integration of curricu- lum, teaching methods, and assessment were not meeting the developmental needs for this new work force.

A few colleges began to use quality processes to improve the teaching/learn- ing process. Applications in the 1980s occurred at Fox Valley Technical Col- lege, Samford College, and Oregon State University (Marchese, 1991). Although often overlooked, medical and dental schools were early adopters of TQM (Brigham, 1993).

There is undoubtedly a need to better identify what is taught, how it is taught, and how academic success can be mea- sured in HEIs. Nevertheless, many edu- cation professionals believe that TQM directed at academics is not the answer. They note that higher education is a very humanistic area where autonomy and academic freedom are highly Val- ued, where specialized faculties avidly protect their turf, and where tradition- bound professors are unlikely to adopt a paradigm that proposes continuous change (Satterlee, 1996).

Proponents of TQM can hardly be ignored in HEIs. Problems in higher education require attention. Teaching and learning need to be improved and assessed. Processes should be adopted to improve the quality of education, increase constituent involvement, empower faculty, and focus on the cus- tomer. One study of 32 HEIs found that administrators and stakeholders be- lieved that their TQM programs were

making a great contribution to organiza- tional effectiveness and that the benefits were greater than the costs (Elmuti, 1999). Successful TQM programs were associated with improved training, a greater degree of goal setting and con- tinuous feedback from constituencies, group approaches to problem solving, and support of leadership.

In the same 1999 study by Elmuti, of the 32 HEIs using TQM, 12 institutions had given up on TQM after a 3-year trial. Reasons cited by administrators for not adopting TQM in higher educa- tion included detrimental effects on cre- ativity, threats of standardization and uniformity, lack of appropriate rewards,

an emphasis on publishing, and profes- sors not accustomed to working in teams. “The number of institutions that have actually implemented TQM suc- cessfully in any meaningful way is com- paratively small, and the gains generat- ed in these institutions often appear to be overshadowed by the time and effort” (Koch & Fisher, 1998, p. 659).

Despite the potential downside of using TQM, many HEIs are using it to improve academic administration, teaching, and learning. The AAHE is interested in assessment and bench- marking, and at the same time the AACSB is supporting the use of CPI programs to improve teaching and learning. Individual schools are using TQM concepts on a variety of issues in addition to the improvement of teach- ingllearning. Because there is such a variety of use found in the literature, identification of the types of use imple- mented over the past decade should be useful. My study identifies issues for which TQM is used, quality techniques being used, the level of use of TQM on teachingllearning, and the changes in these variables over a 3-year period.

A Topology of TQM Use in Educational Institutions

TQM in the curriculum. The most com- mon use of TQM in higher education is teaching it as part of the curriculum in engineering and business schools.

TQM in nonacademic functions. Ad- ministrative and support departments of educational institutions use TQM

processes. Because functions such as human resources management, mainte- nance, and construction are similar to processes in industry, a model for this

type of usage is readily available.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

TQM in academic administration. TQM

processes have been used in the direct administration of academic units in some HEIs. Academic administrative use usually has focused on an assort- ment of educational uses that can be identified as discrete projects in which success is often transparent and easily measurable.

TQM in the core learning process.

Although there is skepticism concern- ing the applicability of TQM to the core learning process, not using these quality concepts in the development, teaching, and assessment process is equivalent to not using TQM in the production or ser- vice areas of businesses. Two applica- tions of TQM to the core learning process are found in the literature.

One application of TQM found in the classroom is to treat classes as micro- organizations. Gilbert et al. (1993) dis- cussed teaching improvements that include establishing a TQM culture in the classroom environment. Students become active team participants in their own learning when quality responsive- ness, relevance, networking, and self- improvement are seen as dimensions of effective teaching. Gartner (1993) and Potocki, Bracatio, and Popleck (1994) also described TQM-type quality approaches targeted at classroom instructional process. Such individual approaches to TQM were not addressed in the study.

A second approach to using TQM- type quality practices in the core learning process is to integrate learning within a discipline and optimally across disci- plines of HEIs. Core competencies such as interpersonal skills, communication skills, decisionmaking skills, and the cri- teria to measure those skills are identi- fied. Quality-type teams are then used to shape course content and teaching tech- niques across a curriculum. Courses are

developed as

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

part of the fabric of a coher- ent curriculum structured in such a waythat complex abilities required of gradu- ates are taught in a stepwise fashion

across courses (Mullin

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Wilson, 1995). Assessment, benchmarking, constituentinvolvement, and continuous improve-

ment are hallmarks of this approach.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Method

Two surveys of 400 colleges and uni- versities throughout the United States were taken, 3 years apart. The surveys investigated the issues on which TQM- type processes were being used, the extent of quality processes used, and if usage was changing over time. We chose the heads of academic business units for the study because we assumed that they had an understanding of TQM-type processes and because the literature indicates that academic business units have been among the first in academia to employ quality processes (Entin, 1993). The same survey instrument was used in both studies. The types of issues on which TQM processes were used includ- ed curricular, nonacademic administra- tive, academic administrative, and core learning process uses. The processes included in the survey were adapted from those used in the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award (Steeples, 1992).

TQM Survey

TQM as Part of the Curriculum

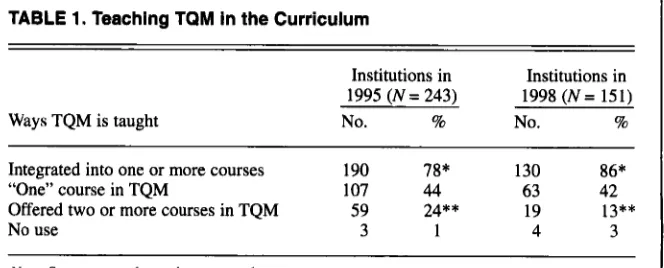

In Table 1, we show how the TQM concepts are being taught in the curricu- lum. The percentage of schools that included TQM concepts in the curricu-

lum increased from

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

78% in 1995 to 86% in 1998. This increase was statisticallysignificant at the .05 level. Those offer- ing two or more courses dropped consid-

erably from 24% to 13%. This decrease was also significant. Though the statis- tics might indicate that schools are offer- ing fewer courses in TQM, it is probable that quality concepts are being taught across disciplines with less emphasis on

individual stand-alone courses.

Administrative

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

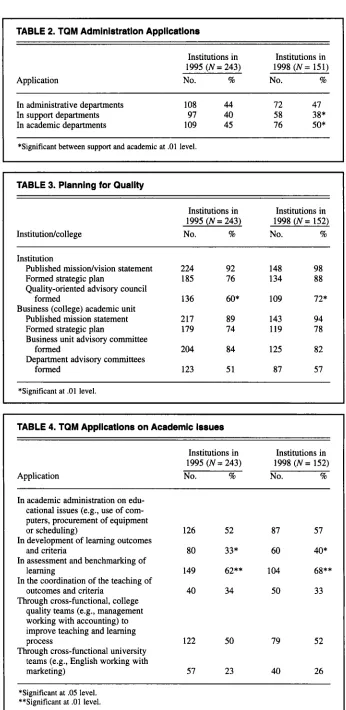

and Academic Uses of TQMThe information in Table 2 indicates the level of use of quality processes in the management of administrative, sup- port, and academic departments. A rela- tively high level of use, ranging form

38% to

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

50%, was found in both 1995 and 1998. Decreases in support depart-ments’ use and increases in academic departments’ use resulted in a signifi- cantly lower level of TQM use by sup- port departments in 1998, compared with academic and administrative use in that same year.

A critical area for making quality improvements in higher education is the development of strategic plans. HEIs should receive an A for efforts in this area (see Table 3). For instance, though only two thirds of major companies have published mission statements, 97% of the HEIs and 94% of the busi- ness units have developed and published mission statements (David, 1999). Sig- nificant increases in strategic planning at the institutional level and increases at the business college level were also found for 1998, relative to 1995 levels, which were already high.

[image:4.612.234.566.575.709.2]Quality-oriented advisory groups also help to improve strategic planning and to garner constituent involvement in TQM programs. Quality-oriented uni-

TABLE 1. Teaching TQM In the Curriculum

Ways TQM is taught

Institutions in Institutions in

1995 ( N = 243) 1998 ( N = 151) No. % No. %

I

Integrated into one or more courses 190 78* 130 86*

“One” course in TQM 107 44 63 42

Offered two or more courses in TQM 59 24** 19 13**

No use 3 1 4 3

Nore. Some respondents chose more than one answer.

*Significant at .05 level. **Significant at .01 level.

NovemberDecember 2000 71

versity advisory councils significantly increased: Sixty percent of HEIs had

them in 1995, compared with

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

72% in 1998. Over 80% of business collegesand 50% of departments had advisory groups, with no significant change over the period studied. These levels indicate widespread use of this type of con-

stituent involvement.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

TQM on Academic Issues and on the Core Learning Process

In Table 4, we show the numbers and percentages of those business units using TQM concepts on four types of academic issues. In 1995, 52% of busi- ness units used quality concepts on edu- cational issues involving teaching, and

in 1998 57%

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

did. The figures in Table 4 also indicate that there have not beensignificant changes from 1995 to 1998 in developing outcomes and criteria and in assessment and benchmarking. But a comparison between the percentage of schools that developed outcomes with the percentage that were assessing and benchmarking yields an apparent con- tradiction. TQM models typically require that assessment flow from previ- ously developed outcomes criteria. In both 1995 and 1998, over 60% of the schools were assessing, while only 40% or less had developed the outcomes/cri- teria to use for assessment.

The application of TQM on the core learning process provides another inter- esting finding: Only one third of the schools attempted to improve the quali- ty of the core learning process by coor- dinating the actual teaching of out- comes and criteria within majors, while the other half were willing to coordinate course offerings between functional

majors (see Table

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

4.)

The significant difference here may result from cross-functional coordination focusing more on general information, whereas coordi- nation of the teaching of outcomes and criteria becomes quite specific and potentially requires continuous, dedicat- ed effort at the departmental or subde- partmental level. In addition, cross-uni- versity teams working to improve teaching and learning were used half

(26%) as much as cross-functional

teams (52%). Such a result may be

expected because faculty members may

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

72 Journal of Education for Business

TABLE 2. TQM Administration Applications

I

Application

Institutions in Institutions in

1995 (N = 243) 1998 ( N = 151)

No. % No. %

In administrative departments 108 44 72 47

In support departments 97 40 58 38*

In academic departments 109 45 76

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

50* *Significant between support and academic at .01 level.TABLE 3. Planning for Quality

Institutiodcollege

Institutions in Institutions in

1995 ( N = 243) 1998 ( N = 152)

No. % No. %

Institution

Published missiodvision statement 224 92 148 98

Formed strategic plan 185 76 134 88

Quality-oriented advisory council

formed 136 60* 109 72*

Business (college) academic unit

Published mission statement 217 89 143 94

Formed strategic plan 179 74 119 78

Business unit advisory committee

formed 204 84 125 82

Department advisory committees

formed 123 51 87 57

*Significant at .01 level.

~~~~~

TABLE 4. TQM Applications on Academic Issues

Institutions in Institutions in

1995 ( N = 243) 1998 ( N = 152)

Application No. % No. %

In academic administration on edu-

cational issues (e.g., use of com- puters, procurement of equipment

or scheduling) 126 52 87 57

In development of learning outcomes

and criteria 80 33* 60 40*

In assessment and benchmarking of

learning 149 62** 104 68** In the coordination of the teaching of

outcomes and criteria 40 34 50 33

Through cross-functional, college

quality teams (e.g., management

working with accounting) to improve teaching and learning

process 122 50 79 52

Through cross-functional university teams (e.g., English working with

marketing) 57 23 40 26

*Significant at .05 level. **Significant at .01 level.

[image:5.612.221.567.25.735.2]find less common ground as they move away from their individual disciplines.

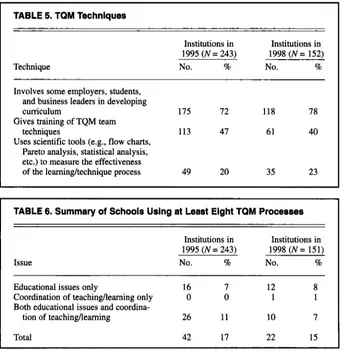

In Table 5, we show the use of three important TQM techniques among the HEIs- constituent involvement, team training, and the use of scientific tools. The results indicate that constituent involvement was high, whereas TQM team training lagged and the use of sci- entific tools was very small. The lack of use of scientific tools is surprising given the background of most college educators.

A review of the variables provided in

Tables

4

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

and 5 indicate that seven of the nine variables increased during the1995-1998 period, with only training decreasing. Although none of the changes were at .05 significance levels, the relationship of the variables seemed to remain stable over time, indicating the reliability of the data.

A final important question asked the heads of business units about the future use of TQM at their institutions over the next 5 years. Respondents in both time frames indicated that it “would

significantly increase,” but there was a

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I

decline at the .01 level of significance in those holding that point of view from

1995 to 1998.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

A Comprehensive TQM Model?

Finally a litmus test was used to deter- mine the number of institutions using a comprehensive model of TQM. Table 6

provides a summary of business units using eight or more TQM processes on educational issues only, or in the coordi- nation of teachingllearning, or on both educational issues, and the coordination of teachingearning. The data indicate that only a small number of institutions, 17% in 1995 and 15% in 1998, were

employing a complete TQM model.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Conclusion

Institutions of higher education should be lauded for their focus on strategic planning, an important element in demonstrating and improving effec- tiveness. Mission development, strategy determination, and the setting of goals

have increased significantly over the

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

[image:6.612.47.390.393.746.2]1

I

TABLE 5. TQM TechniquesTechnique

Institutions in Institutions in 1995 (N = 243) 1998 (N = 152)

No. % No. %

Involves some employers, students, and business leaders in developing

curriculum 175 72 118 78 Gives training of TQM team

techniques 113 47 61 40 Uses scientific tools (e.g., flow charts,

Pareto analysis, statistical analysis, etc.) to measure the effectiveness

of the learninghechnique process 49 20 35 23

I

TABLE 6. Summary of Schools Using at Least Eight TQM ProcessesIssue

Institutions in Institutions in 1995 (N = 243) 1998 (N = 151)

No. % No. %

Educational issues only 16 7 12 8 Coordination of teachinghearning only 0 0 1 1

tion of teachingfleaming 26 11 10 7 Both educational issues and coordina-

Total 42 17 22 15

time period surveyed and appear to meet or exceed levels found in the busi- ness world. This is being accomplished at both the university and college levels. Business colleges also get high marks for involving constituents. More then 78% of business colleges indicated that they are involving employers, business leaders, and students in the development of curriculum. The use of advisory boards at 80% of the colleges and a majority of the departments are addi- tional indicators of constituency involve- ment and empowerment. Further, over

50% of the colleges are using cross- functional teams at the college level.

Most HEIs use various forms of assessment, and our study indicates that by 1998 more than two thirds of busi- ness colleges were also attempting to benchmark the assessment. Yet many schools are not managing the core learn- ing process through development of teaching outcomes/criteria or the coor- dination of teaching/learning across courses. Consequently, the process of benchmarking and improving the teach- ing and learning process is likely to be delayed. Benchmarked assessment typi- cally takes the form of standardized objective tests. Important skills such as oral and written presentation skills, team skills, and decisionmaking skills are difficult to measure thorough objec- tive tests and are unlikely to be bench- marked across HEIs without develop- ment and coordination of learning directed at the core learning process.

Several quality processes often used in TQM are not used to a great extent among the colleges studied. It is possi- ble that colleges are just beginning to use the TQM paradigm, or are not applying the paradigm in the same way. It is also possible that academic processes do not lend themselves readi- ly to the same techniques used in indus- try and that an academic model of TQM is developing. In addition, there seems to be a leveling off of the use of quality process in both the type and percentage of quality processes employed.

Overall, it appears that colleges of business are making strides in improv- ing their services. They are doing it with a variety of quality processes. In indus- try, as in HEIS, a success rate of more than 20% to 30% is unlikely. In addi-

NovembedDecember 2000

73

tion, HEIs are using a model of TQM that leaves most of the education process up to the individual faculty member. Time constraints, research needs, irregular teaching schedules, use of part-timers, organizational culture, and academic freedom make it difficult to employ a comprehensive TQM pro- gram in academia. Nevertheless, many business colleges are attempting the process, and some institutions are likely to succeed. Most institutions are at least likely to benefit from this attempt to improve the quality of their institutions

by better serving their constituencies.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

REFERENCES

American Association of Higher Education, Con- sortium for the Improvement of Teaching.

(1992).

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Learning and assessment/shared edu-cational assumptions. Distributed at the

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

AAHEConference on Assessment, June 22.

Becker,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

S. (1993). TQM does work: Ten reasonswhy misguided attempts fail. Management

Review, May, 32-33.

Bergquist, T. M.,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Ramsing, K. D. (1999). Mea-suring performance after meeting award crite- ria. Quality Progress, September, 53-58. Brigham, S. E. (1993). Lessons we can learn from

industry. Change, 25(3),42-48.

Buch, K., & Shelnutt, W. J. (1995). UNC Char- lotte measures the effects of its quality initia- th tive. Quality Progress, July, 73-77.

ed.) (p. 9). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Elmuti, D., Kathawala, Y., & Manippallili, M.(1996). Are total quality management pro- grammes in higher education worth the effort? International Journal of Quality and Reliability Management,l3(6), 2945.

Entin, D. (1993). Boston: Less than meets the eye. Change, 3, 28-3 1.

Gartner. W. B. (1993). Dr. Deming comes to col- lege. Journal of Management Education, 17(2), 143-1 58.

Gilbert, J. P., Keck, K. L., & Simpson, R. D. (1993). Improving the process of education: TQM for the college classroom. Innovative Higher Education, 1, pp. 65-85.

Hoachlander, G. E. (1998). Assessing assessment. Techniques: Making Education & Career Con- nections, 73(3), 14-17.

Koch, I. J., & Fisher J. L. (1998. Higher education David, F. R. (1999). Strategic managment (7

and total quality management. Total Quality

Management, 9(8),

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

659.Marchese, (1991). TQM reaches the academy. AAHE Bulletin, 44(3), 3-9.

Mathew, J., & Katel, P. (1992, September 7). The costs of quality. Newsweek, pp. 48-49. Mullin, R., &Wilson, G. (1995). Quality in edu-

cation: A new paradigm and exemplar. In CQI: Making the transition to education (2"* ed.). Maryville, MO: Prescott Publishing.

Porter, L., & McKibbin, L. (1988). ManaHment development: DriB or thrust into the 21 cen- tury? New York McGraw-Hill.

Potocki, K., Bracatio, R., & Poplek, P. R. (1994). How TQM works in a university classroom. Journal of Quality and Participation, 17( I),

Satterlee, B. (1996). Continuous improvement and quality: Implications for higher education. Viewpoints, September, ED 399 845. Steeples, M. (1992). The corporate guide to the

Malcolm Baldrige Award (p. 383). Milwaukee, WI: ASQ Quality Press.

Tai, L. S., & Przasnyski, Z. H. (1999). Baldrige award winners beat the S & P 500. Quality Progress, April, 45-5 1.

Vazzana, G. S., Winter, J. K., & Waner, K. K.

(1997). Can TQM fill a gap in higher educa- tion? Journal of Education for Business, 72(5), 313-316.

68-74.

JOURNAL OF

EDUCATION

FOR

BUSINESS

..B B W W B M W rn.. B m B W.. BWB MW.

,

YES!

I would like to order a one-year subscription to the Journal of Education,

rn

ORDER FORM

for Business published bimonthly. I understand payment can be made to Heldref

Publications or charged to my VISAMasterCard (circle one). $41 .OO Individuals $70.00 Institutions

ACCOUNT # EXPIRATION DATE

SIGNATURE

NAMUl NSTlTUTl ON rn

rn

ADDRESS rn

CITY/STATE/ZI P

COUNTRY rn

ADD $15.00 FOR POSTAGE OUTSIDE THE U.S. ALLOW 6 WEEKS FOR DELIVERY OF FIRST ISSUE.

SEND ORDER FORM AND PAYMENT TO:

HELDREF PUBLICATIONS, Journal of Education lor Business

1319 EIGHTEENTH ST., NW, WASHINGTON, DC 20036-1802 PHONE (202) 296-6267 FAX (202) 296-5149

SUBSCRIPTION ORDERS 1(800)365-9753, www.heldref.org

The Journal of Education for Business readership

includes instructors, supervi-

sors, and administrators at

the secondary, post- secondary, and collegiate levels. The Journal features basic and applied research- based articles in accounting, communications, economics, finance, information sys- tems, management, market- ing, and other business dis- ciplines. Articles report or share successful innovations, propose theoretical formula- tions, or advocate positions on important controversial issues and are selected on a blind, peer-reviewed basis.