Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 19 January 2016, At: 19:47

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Post-crisis monetary and exchange rate policies in

Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailands

George Fane

To cite this article: George Fane (2005) Post-crisis monetary and exchange rate policies in Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailands, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 41:2, 175-195, DOI: 10.1080/00074910500117024

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910500117024

Published online: 18 Jan 2007.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 115

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/05/020175-21 © 2005 Indonesia Project ANU DOI: 10.1080/00074910500117024

α ∗

I am grateful for help from officials of the central banks of Indonesia, Malaysia and Thai-land. I have also received many helpful comments from Stephen Grenville, Lloyd Ken-ward and Stephen Marks. The opinions expressed and any remaining errors are of course my responsibility alone.

POST-CRISIS MONETARY AND EXCHANGE RATE

POLICIES IN INDONESIA, MALAYSIA AND THAILAND

George Fanea ∗

Australian National University

This paper surveys the post-crisis monetary and exchange rate policies of Indo-nesia, Thailand and Malaysia. Malaysia has pegged the ringgit while Indonesia and Thailand have adopted heavily managed exchange rates. Under their IMF pro-grams, Thailand and Indonesia set base money targets, but Thailand has moved, and Indonesia is now moving, to inflation targeting, using interest rates as the short-term instrument. Malaysia also sets interest rates. The ability of the three cen-tral banks to set interest rates and also pursue an exchange rate target with an inter-est rate target has been bolstered by rinter-estrictions on the internationalisation of the domestic currency. The three central banks have also had to sterilise the monetary effects of their foreign exchange interventions. It is argued that inflation targeting is now a good policy choice, but that a more freely floating exchange rate would be better than sterilisation of balance of payments surpluses or deficits.

INTRODUCTION

The monetary and exchange rate responses of Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia to the dramatic speculative attacks on their currencies in 1997 were very differ-ent. Having sought and obtained the help of the IMF, Indonesia and Thailand abandoned long-standing policies of pegging their currencies to baskets that were overwhelmingly dominated by the dollar, and announced the adoption of floating exchange rate regimes and restrictive monetary policies based on targets for restraining the rate of growth of base money (M0).

In the first nine months of the 1997–98 crisis, Bank Indonesia (BI) completely failed to meet the monetary targets announced in the Indonesian government’s letters of intent (LOIs) to the IMF. This happened as a result of last-resort lending to weak banks that was far in excess of the amount needed to meet the public’s demand to convert deposits into cash (Fane and McLeod 1999: tables 2, 3 and 4; Kenward forthcoming; McLeod 2003: 305–6; Djiwandono 2004: 65–6). In the sec-ond half of 1998, BI did achieve its base money targets. As a result, interest rates

1The 30-day interest rate on SBI (Sertifikat BI, certificates of deposit at BI) peaked at 70.4% in August 1998 before falling to 35.5% in December 1998; by August 1999 it was down to 13.1% (CEIC Asia Database). Inflation fell rapidly and the exchange rate appreciated from Rp 15,000 to Rp 7,500/$ in just over three months (McLeod 2003: 305–6).

and inflation both fell rapidly and the exchange rate appreciated.1During the remainder of the IMF program, the M0 targets were not always met, but they were never again missed as badly as they had been before mid-1998.

Under Thailand’s Standby Agreement with the IMF, the Bank of Thailand (BOT) allowed the exchange rate to float, and from 1997 until 2000 it targeted base money for periods that ranged from three months to one year ahead. On a day-to-day basis, the BOT adjusted its net supply of liquidity to the interbank money market with the aim of minimising fluctuations in short-term interest rates. The BOT’s policy was to put upward pressure on interest rates if base money was run-ning ahead of the medium-term targets and downward pressure on interest rates if base money was below them. Although there were some substantial deviations between the actual and targeted values of base money, the deviations mainly involved base money being below the announced targets.

Malaysian policy makers initially hoped that they would avoid the crises that overtook Thailand and Indonesia in the second half of 1997, and did not seek assis-tance from the IMF. In December 1997, the Malaysian finance minister, Dr Anwar Ibrahim, introduced policies of fiscal and monetary restraint that were described as ‘IMF policy without the IMF’; however, it seems that Prime Minister Mahathir did not support these policies, and they were reversed over the next eight months (Athukorala 2001: 65–6). A complete break with the IMF’s prescription for dealing with the Asian crisis occurred in September 1998, when Malaysia adopted mildly expansionary monetary and fiscal policies, pegged the currency at Rgt 3.80/$ and severely tightened its capital account controls (Athukorala 2001: chapter 6).

During the course of the Asian crisis, all three central banks tightened the measures designed to prevent the use of their currencies in international financial markets. These measures involve making it illegal for residents to make domes-tic currency-denominated loans to non-residents.

In May 2000, the BOT moved away from targeting base money and began to set short-term interest rates so as to achieve a medium-term inflation goal. Even though its Standby Agreement with the IMF has now ended, BI continues to have annual targets for M0. However, these targets are now merely one of a checklist of variables that BI monitors when deciding how to set short-term interest rates. BI has announced that it will adopt a similar inflation targeting regime to that of Thailand and has taken some steps in this direction (Alamsyah et al. 2001). Despite nominally operating floating exchange rate policies, both BOT and BI intervene heavily in the foreign exchange market and have to sterilise the effects of these interventions in the domestic money market in order to keep short-term interest rates at their set levels.

Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) has now removed its exchange controls, other than those designed to prevent the use of the ringgit in offshore financial centres. So far, it has continued to keep the ringgit pegged to the dollar, but it

2In addition to Thailand, the countries to adopt inflation targeting include Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, the Czech Republic, South Korea, New Zealand and the United Kingdom.

less also sets short-term interest rates and it too therefore has to sterilise the mon-etary effects of its exchange market interventions.

In the aftermath of the crisis, there has therefore been a considerable conver-gence in the policies of the three central banks. If BNM were to allow the ringgit to float, while still intervening heavily in the foreign exchange market, and if both BI and BNM were to set firm medium-term inflation goals, the remaining differ-ences would be trivial.

The next section begins with a statistical summary of real growth, monetary growth, inflation and interest rates in the three countries and then discusses infla-tion targeting. This policy, which has become increasingly popular with central banks in both developed and developing countries, has been adopted by the BOT and is in the course of being adopted by BI.2The third section begins with a

dis-cussion of the decision by all three central banks to intervene actively in the for-eign exchange market and to sterilise the monetary effects of such intervention in the short-term money market. The ability of central banks to do this is bolstered by restrictions on the internationalisation of the domestic currency. These restric-tions are the focus of the remainder of the section. The fourth section deals with the technical aspects of monetary policy in the three countries, and the final sec-tion summarises the similarities and differences among the policies of the three central banks and suggests tentative appraisals of these policies.

POST-CRISIS MONETARY OUTCOMES AND STRATEGIES Monetary Growth, Real Growth, Inflation and Interest Rates

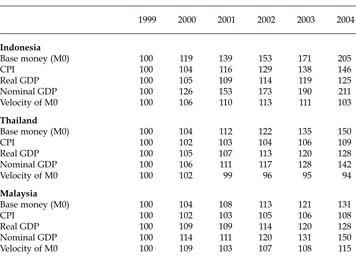

Table 1 provides an overview of the evolution of the supply of base money and of its velocity of circulation in the three countries since 1999. All the series are indexed at 100 in 1999, but the qualitative results would not be greatly changed by using 1998 or 2000 as the starting year.

Between 1999 and 2004, real GDP grew by 25% in Indonesia and by 28% in both Malaysia and Thailand. In contrast to these fairly similar rates of real growth, base money grew much faster in Indonesia (105%) than in Malaysia (31%) or Thailand (51%). This large difference in monetary growth between Indo-nesia, on the one hand, and Malaysia or Thailand, on the other, was enough to dwarf the changes in the velocity of circulation of base money, and inflation was therefore much faster in Indonesia than in the other two countries. The much steeper rise in the consumer price index (CPI) in Indonesia than in Malaysia or Thailand (table 1) confirms the familiar finding that a large expansion in base money relative to GDP is virtually guaranteed to produce rapid inflation. How-ever, the changes in velocity of circulation of base money were also quite substan-tial. In Indonesia, it rose by 13% between 1999 and 2002, but this rise was largely reversed over the next two years. In Malaysia, velocity rose by 15% between 1999

TABLE 1 Base Money, Nominal GDP and Velocity of Base Moneya (1999 = 100)

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

Indonesia

Base money (M0) 100 119 139 153 171 205

CPI 100 104 116 129 138 146

Real GDP 100 105 109 114 119 125 Nominal GDP 100 126 153 173 190 211 Velocity of M0 100 106 110 113 111 103

Thailand

Base money (M0) 100 104 112 122 135 150

CPI 100 102 103 104 106 109

Real GDP 100 105 107 113 120 128 Nominal GDP 100 106 111 117 128 142 Velocity of M0 100 102 99 96 95 94

Malaysia

Base money (M0) 100 104 108 113 121 131

CPI 100 102 103 105 106 108

Real GDP 100 109 109 114 120 128 Nominal GDP 100 114 111 120 131 150 Velocity of M0 100 109 103 107 108 115

aData for base money (M0) are averages of the monthly figures; velocity of M0 is defined

as nominal GDP divided by M0.

Source: CEIC Asia Database.

3The rise in velocity in Malaysia can be explained, at least in part, by the reduction in statu-tory reserve requirements. Likewise, the fall of velocity in Indonesia in 2004 is associated with an increase in statutory reserve requirements in that year. The (modest) fall in veloc-ity in Thailand does not have any equally simple explanation.

and 2004, whereas in Thailand it fell by 6% over the same period.3As a result, although base money grew more rapidly in Thailand than in Malaysia, inflation was faster in Malaysia than in Thailand.

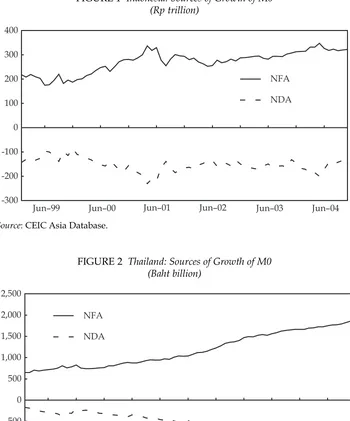

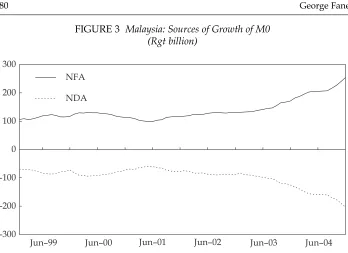

Base money can be expressed as the sum of the net foreign assets (NFA) and net domestic assets (NDA) of the central bank. This identity is used in figures 1, 2 and 3 to analyse the proximate sources of changes in the supply of base money in the three countries. One striking feature of these charts is the strong upward trend in NFA in all three countries. Whatever the central banks of Thailand and Indonesia may say about floating their currencies, figures 1 and 2 show that they have actually intervened heavily and systematically in the foreign exchange market.

A second striking feature of figures 1, 2 and 3 is the extent to which, in each case, NDA and NFA are mirror images of each other. This results from the

Jun–99 Jun–00 Jun–01 Jun–02 Jun–03 Jun–04 -300

-200 -100 0 100 200 300 400

NFA

NDA

FIGURE 1 Indonesia: Sources of Growth of M0 (Rp trillion)

Source: CEIC Asia Database.

Jun–99 Jun–00 Jun–01 Jun–02 Jun–03 Jun–04

-1,500 -1,000 -500 0 500 1,000 1,500 2,000 2,500

NFA

NDA

FIGURE 2 Thailand: Sources of Growth of M0 (Baht billion)

Source: CEIC Asia Database.

tral banks setting exogenous targets for both the exchange rate and the short-term interest rate. Of course, BOT and BI have not pegged their currencies rigidly to the dollar in the way that BNM has, but all three central banks have regularly intervened in the foreign exchange market, and these interventions

Jun–99 Jun–00 Jun–01 Jun–02 Jun–03 Jun–04 -300

-200 -100 0 100 200 300

NFA

NDA

FIGURE 3 Malaysia: Sources of Growth of M0 (Rgt billion)

Source: CEIC Asia Database.

4In the absence of any other changes, an exchange rate fluctuation causes equal and oppo-site changes in NDA and NFA, leaving M0 unchanged. The reason for the change in the domestic currency value of NFA is obvious; the equal and opposite change in NDA arises because one of its negative components is the net wealth of the central bank in domestic currency, which is directly affected by capital gains, or losses, on NFA. For this reason, exchange rate fluctuations cause the charts to exaggerate the extent to which the central banks have actually sterilised NFA. Without knowing the composition of NFA between dollars, yen, euro and so forth, it is impossible to make accurate allowances for this effect.

have normally involved purchasing foreign exchange to prevent the apprecia-tion of the domestic currency. At the same time, all three central banks have also intervened in the short-term money markets on a day-to-day basis to absorb liquidity, or on rare occasions to inject it, so as to keep short-term rates at their target levels. The combination of these two policies has meant that open market purchases of securities by each central bank have been determined endoge-nously to sterilise most of the effects of its foreign exchange market interventions on the supply of base money.4

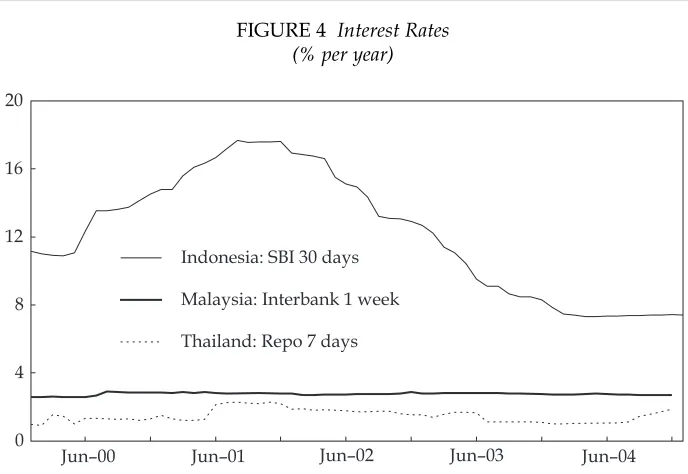

Figure 4 plots the course of nominal interest rates in the three countries. Just as a large and rapid increase in base money almost invariably leads to rapid infla-tion, so does rapid inflation almost invariably lead to high nominal interest rates. Since inflation has been much higher in Indonesia than in Thailand and Malaysia, it is therefore not surprising that nominal interest rates in Indonesia have been much higher than those in the other two countries.

Jun–00 Jun–01 Jun–02 Jun–03 Jun–04 0

4 8 12 16 20

Indonesia: SBI 30 days

Malaysia: Interbank 1 week

Thailand: Repo 7 days

FIGURE 4 Interest Rates (% per year)

Source: CEIC Asia Database.

5For example, the average rate of core inflation in the last quarter of 2004 is defined as the average of the rates of core inflation for October, November and December 2004, relative to the same months in 2003. Since the monthly increases were 0.6% in each case, the aver-age core inflation rate for the quarter was also 0.6%.

Inflation Targeting in Thailand and Indonesia

Thailand’s experience with inflation targeting is interesting because it offers an example to the other countries in the region of a monetary strategy that has so far worked well. BI has announced that it too intends to adopt inflation targeting, but has not moved as far in this direction as Thailand has. Malaysia has pegged the ringgit against the dollar, but is now facing growing pressures to revalue. If it does so, it may well opt for a managed float, and it would then presumably look at the Thai evidence on the efficacy of inflation targeting.

Although Thailand’s Standby Agreement with the IMF did not end until July 2003, the BOT’s stated medium-term target variable was changed from base money to inflation in 2000. Under the new regime, the Monetary Policy Commit-tee (MPC) of the BOT fixes short-term interest rates at the level that it thinks will keep the ‘core’ inflation rate within the announced target range of zero to 3.5% per year, and it has so far succeeded in achieving this goal. Core inflation is meas-ured by excluding energy and raw food prices from the CPI, and calculating the year-on-year percentage increase of the resulting index on a monthly basis. The target range for core inflation applies to the average of the monthly figures for each quarter.5

6Before May 2001, the BOT’s lending rate was set by the Monetary Policy Board. Other minor changes occurred at the same time as the change in the title from ‘Board’ to ‘Com-mittee’.

The MPC meets about once per month to set the 14-day repurchase (‘repo’) rate.6Under a 14-day repo contract, one party sells a high quality security, such

as a treasury bill, to another party, but makes a commitment to buy it back at a slightly higher price after 14 days. In effect, the first party borrows from the sec-ond party using the high quality security as collateral. The interest rate on the loan is determined by the difference between the sale and the repurchase price.

The MPC uses the repo rate to influence inflation, raising the interest rate to choke off inflation if it appears to be too rapid and lowering the interest rate if inflation would otherwise be negative. Because of the width of the target zone, the MPC can also devote some attention to other factors, such as the strength of real growth. So far, the MPC has been able to keep core inflation within the target zone; admittedly, the zone is quite wide, but the MPC deserves credit for keeping inflation low and for anticipating how inflation is likely to respond to its actions and to other internal and external developments.

The reason given for the switch from targeting base money to targeting infla-tion was the claim that the relainfla-tionship between base money and output growth had become weaker than it used to be (Bank of Thailand 2004: 3). In fact, the case for targeting M0 rests on there being a stable relationship between it and the level of nominal GDP, or perhaps between it and the price level, rather than on there being a stable relationship between it and output growth. Given this and given that the BOT has not tried to demonstrate that there is a stable relationship between core inflation and output growth, it seems likely that the reason for the switch probably had more to do with changing fashions, in Thailand and else-where, on how best to operate monetary policy. The relative merits of the two alternative nominal targets—inflation and M0—are discussed below. The new policy has strong similarities with the approach pioneered by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ), and explanations of the new policy on the BOT’s web-site explicitly compare it to that of the RBNZ.

When BI adopts inflation targeting, this will not mark a sharp break with what has gone before, since the setting of base money targets was always intended to be a means to controlling inflation, rather than an end in itself. Besides, tentative versions of inflation targeting formed part of several of Indonesia’s LOIs to the IMF. The January 1998 LOI dropped the base money target that had been part of the original IMF package and announced that inflation would be kept to less than 20% in 1998. In the event, the CPI rose by 21% in just the first two months of 1998. The LOI of April 1998 reinstated base money as the proximate target of monetary policy; it discussed the likely future rate of inflation, without making it a target. The LOI of July 1998 stated that ‘inflation is to be reduced to a single-digit annual rate within no more than two years’. The LOI of January 2000 set base money tar-gets that were designed to keep annual inflation below 5%. The actual CPI increase between December 1999 and December 2000 was 9.3%. Following a fur-ther increase in inflation to 12.5% for the 12 months ending in December 2001, the LOI of 13 December 2001 announced that the ‘strategic goal’ of monetary policy

was to restore single-digit inflation by the end of 2002. The actual CPI increase between December 2001 and December 2002 was 9.9%. In September 2004, the governor of BI announced a policy of ‘low and stable inflation’ for the period 2005–08. He stated that senior staff at BI were working on the details of how this is to be achieved, but at the time of writing (February 2005) these details have yet to be announced (Bank Indonesia 2004).

THE PURSUIT OF ‘ACTIVE’ MONETARY AND EXCHANGE RATE POLICIES AND THE NON-INTERNATIONALISATION OF DOMESTIC CURRENCY

Combining Active Monetary Policy with Active Exchange Rate Policy

All three central banks have combined ‘active’ monetary policies with ‘active’ exchange rate policies. In the case of exchange rate policy, ‘active’ is used here to mean that the central bank has either fixed the nominal exchange rate (Malaysia) or intervened heavily in the foreign exchange market to manage a rate that is described as floating. In the case of monetary policy, ‘active’ is used to mean that the central bank sets the short-term interest rate in the domestic money market. Under perfect capital mobility, a central bank would have to choose between active monetary policy and active exchange rate policy. The ability of the three central banks to pursue both policies, at least in the short term, is due partly to the reluctance of non-residents to hold large open positions in any of the relevant currencies and partly to controls in each country that restrict the ‘internationali-sation’ of the domestic currency—that is, controls designed to insulate onshore interest rates from offshore speculative pressures by preventing residents making loans to non-residents that are denominated in the domestic currency, and by pre-venting the emergence of offshore markets in securities denominated in the domestic currency.

With some exceptions, such as the speculative flurry against the rupiah in mid-2004, most of these interventions have involved acquiring foreign exchange reserves so as to prevent the appreciation of the real exchange rate—that is, to prevent an increase in the ratio of the price of non-traded goods to the price of traded goods—and thus raise the profitability of industries producing exports and import-competing products.

Sterilising balance of payments surpluses to prevent exchange rate apprecia-tion is of course what the Asian central banks did in the boom period that pre-ceded the 1997 financial crisis, and it probably contributed to the occurrence of the crisis. If, instead of sterilising a capital inflow, the central bank allows the exchange rate to appreciate, the inflow would be self-correcting, because it would depress the returns to domestic assets by driving up their domestic currency prices and, a fortiori, their foreign currency prices. If the exchange rate is allowed to float, a foreign capital inflow will reduce domestic interest rates. If the inflow would have been $100 million at the initial level of interest rates, the final inflow will be less than $100 million because of the fall in domestic interest rates; part of this reduced amount will finance increased real investment and the rest will be matched by higher non-resident holding of domestic private securities. If instead, the exchange rate is held constant and the effects of the capital inflow on the money supply are sterilised by the sale of short-term bills by the central bank,

the domestic interest rate will not fall and the final inflow will be the initially planned $100 million, not some lesser amount. Further, the whole of the $100 mil-lion will now go into increased non-resident holdings of official short-term bills and real investment will not rise. Sterilisation therefore switches off the stabilis-ing effects of a capital inflow on interest rates and investment. If the central bank matches its short-term domestic currency-denominated liabilities with short-term foreign currency-denominated assets, the reversal of the inflow would not be a problem, provided that the authorities were willing to run down their foreign currency-denominated assets in defence of the domestic currency, and provided that a sudden capital outflow did not generate speculation against the domestic currency. But since these conditions may not hold, managing the exchange rate and sterilising the monetary effects of balance of payments surpluses is a danger-ous policy.

Offshore Markets in Rupiah, Baht and Ringgit

The growth of offshore currency markets can occur as a result of globalisation, but is often accelerated by attempts to escape from onshore financial regulations. Both factors were important causes of the growth of the eurodollar market—the largest of all offshore currency markets—and both were also important in the growth of offshore markets in Asian currencies before 1997. Offshore markets in rupiah, baht and ringgit existed in Singapore and in some other international financial centres. International banks in these offshore centres were able to accept deposits in ringgit, baht and rupiah and to engage in spot and swap transactions between these currencies and the major international currencies, particularly the dollar. Perhaps because of BNM’s relatively tight domestic financial controls, the offshore ringgit market in Singapore was particularly large until BNM regulated it out of existence in September 1998.

Foreign exchange swap contracts, and regulations designed to restrict the use of such contracts, have been particularly important in offshore currency markets. Box 1 explains the mechanics of these contracts.

Governments and central banks often view the internationalisation of their currencies with hostility, since it reduces the effectiveness of their regulation of the domestic financial system; it also weakens their control over interest and exchange rates, by allowing speculation in offshore markets to have a direct impact on domestic interest rates and the spot exchange rate—or on official reserves, if the central bank intervenes to defend the spot exchange rate.

As an example of how offshore speculation can affect onshore interest rates, consider an offshore speculator who does not hold rupiah but expects that the rupiah will weaken sharply against the dollar. If correct, this speculator can make a profit by borrowing in rupiah, selling the rupiah for dollars in the spot foreign exchange market, and then buying dollar-denominated securities. The speculator could achieve the same result by swapping dollars for rupiah, using the rupiah to buy back dollars in the spot market and then making dollar-denominated loans. Whether done directly, or indirectly via the swap market, these transactions would put upward pressure on onshore rupiah interest rates and downward pressure on the value of the rupiah. To resist these pressures without restricting access to the spot market in foreign exchange, the Indonesian authorities would have to make it illegal for residents to lend directly to non-residents in rupiah and

BOX1 THE MECHANICS OF FOREIGN EXCHANGE SWAPS

A foreign exchange swap has two parts. In the first part, the two parties to the con-tract exchange amounts of two currencies that have the same value in the spot mar-ket; in the second part, the initial exchange is reversed at a rate that reflects the originally expected change in the spot exchange rate. As an illustration, consider a swap between rupiah and dollars, on 1 January when the exchange rate in the spot market is Rp 8,000/$. In the first part, the two contracting parties exchange amounts of rupiah and dollars that have the same value in the spot market, for example Rp 8 billion and $1 million. In the second part, which might occur three months later, on 1 April, the initial swap is reversed, but at an exchange rate that reflects the differ-ence between rupiah and dollar interest rates. If the interest rate for borrowing and lending in rupiah is 12% per year, and therefore roughly 3% for three months, and the interest rate for borrowing and lending in dollars is 4% per year, and therefore roughly 1% for three months, the exchange rate for the second part of the transac-tion, the reversal of the original swap, will be about Rp 8,160/$, that is the initial exchange rate scaled up by the 2% difference between the three-month interest rates on rupiah and dollars. ‘Roughly’ and ‘about’ have been used because this numeri-cal example uses simple interest and ignores the minor complications of compound interest. The party that handed over Rp 8 billion in exchange for $1 million on 1 Jan-uary will be returned about Rp 8.16 billion in exchange for $1 million on 1 April.

Restrictions on the ability of onshore banks to enter into swaps with non-residents in which the onshore bank initially provides domestic currency in exchange for foreign currency are an essential part of an exchange control system that is designed to prevent the internationalisation of the domestic currency. The reason is that such swaps effectively involve the onshore bank making a domestic denominated loan to the non-resident, matched by a foreign currency-denominated loan from the non-resident to the domestic bank.

7The rupiah weakened from Rp 8,661/$ in April 2004 to Rp 9,415/$ in June 2004 (CEIC Asia Database).

they would also have to restrict indirect rupiah lending via the swap market. As explained below, all three central banks have responded to the Asian crisis by imposing and tightening such restrictions.

Restrictions on the Internationalisation of the Rupiah, Baht and Ringgit

Soon after the outbreak of the Asian crisis, BI issued a regulation to restrict indi-rect lending by onshore banks to non-residents via the swap market (Bank Indo-nesia 1998: 65). It further tightened its restrictions on the internationalisation of the rupiah following the flurry of speculation that saw the dollar value of the currency fall by 8% between April and June 2004.7Then, in September 2004, BI issued a new prudential regulation on the net open position (NOP) in foreign exchange of the commercial banks—that is, the difference between the values of

each bank’s foreign currency assets and liabilities, relative to their capital—that has had the effect of further restricting their access to the swap market. Previ-ously, each bank’s overall NOP had to be less than 20% of its capital, and this requirement was monitored at the end of each day. Under the new regulations, both the balance sheet NOP and the overall NOP, that is, the sum of the on-balance sheet NOP and the off-on-balance sheet NOP, must be less than 20% of cap-ital, and this condition must be met at midday, as well as at the end of the day. The new regulation has substantially hindered banks’ ability to trade in the swap market. The reason follows from the fact that, as explained in box 1, a for-eign exchange swap has two parts: in the first, currencies are swapped, in the sec-ond the original swap is reversed. Because of this reversal, the swap does not change either party’s overall exposure to foreign exchange risk. An Indonesian bank that swaps rupiah for dollars in the first part of the transaction incurs an obligation to return dollars for rupiah in the second part that exactly offsets the net open position that would be produced by the first part of the transaction, if it were undertaken in isolation. A bank’s overall NOP is therefore unaffected by swap market transactions, and these transactions were therefore not restricted by Indonesia’s pre-September 2004 regulations on each bank’s overall NOP. Under the new regulations, the initial exchange of currencies is recorded on-balance sheet, but the offsetting commitment to reverse the swap is off-balance sheet. The new regulations therefore prevent a swap market transaction that would cause the bank’s net on-balance sheet open position to exceed 20% of its equity.

Policies to prevent the internationalisation of the baht have been part of the BOT’s response to the Asian crisis. In January 1998, it imposed tight limits on baht-denominated credit facilities provided by Thai financial institutions to non-residents unless there was an underlying trade or investment activity in Thailand (Bank of Thailand 2000), and these restrictions remain in place.

Even before the outbreak of the crisis, direct lending by Malaysian residents to non-residents in ringgit had been prohibited by BNM’s exchange controls, and in August 1997 BNM effectively banned indirect lending by setting very low limits on the amounts of ringgit that onshore banks could offer to swap with non-residents, unless there was an underlying real transaction, such as trade or foreign direct investment. Then, as part of the exchange controls introduced by Malaysia in September 1998, the offshore market in ringgit deposits was closed. This was achieved by allowing holders of offshore ringgit deposits a grace period of one month in which to repatriate their deposits to Malaysia, after which it became illegal for onshore banks to accept inward transfers of ringgit from offshore banks.

Costs and Benefits of Restricting

Internationalisation of the Domestic Currency

The advantage of allowing the domestic currency to be ‘internationalised’, as Australia did when it abolished all exchange controls in 1983, is that this adds to the liquidity of the domestic money market and of the forward and swap markets in foreign exchange. The smaller the domestic financial system, the more impor-tant are these advantages. Allowing international banks to engage freely in the swap and forward markets gives these markets, which are used by traders and investors, as well as by speculators, much greater depth than they would have if

8SBI with six months to maturity were discontinued in 1999.

restricted purely to onshore banks. Access to offshore markets in local currency adds to the liquidity of the onshore banks in the onshore money market. If these banks have shortages or surpluses of liquidity in domestic currency, they can bor-row from, or lend to, offshore banks.

The disadvantage of allowing the domestic currency to be internationalised is, of course, that it means that offshore speculative pressures are directly transmitted to onshore interest rates and the onshore foreign exchange market. But there are other, more effective, ways to avoid the costs of destabilising speculation, without forgoing the benefits of internationalisation of the domestic currency. These include giving the central bank independence to pursue a credible target, such as low inflation, or slow monetary growth; encouraging the entry of international banks; improving bankruptcy laws (since the financial system cannot work effi-ciently if sanctions against defaulters are ineffective); and raising the capital ade-quacy ratios of banks and other financial institutions. Since it would be hard to guarantee that even these policies would be completely effective, and since the costs of the financial crisis of 1997–98 proved to be very high, it is not surprising that all three countries maintain tight restrictions on the internationalisation of their currency. While this safety first approach can be defended, the three govern-ments can be criticised for not also moving much more vigorously to implement the first best policies, listed above, for reducing financial sector vulnerability.

TECHNICAL ASPECTS OF MONETARY POLICY Monetary Policy Techniques: Indonesia

BI uses two instruments for conducting open market operations, FASBI and SBI. FASBI (Fasilitas Simpanan BI, BI Deposit Facility) is a term deposit facility. At present all FASBI deposits are accepted for a term of seven days. SBI are certifi-cates of deposit that are currently issued for maturities of one month and three months.8By accepting all deposits offered at the FASBI rate and by adjusting the

outstanding volumes of one-month and three-month SBIs, BI can control short-term interest rates. Neither FASBI nor SBI is part of base money, so when banks move their funds from vault cash or excess reserves to either of these instruments, NDA and base money are both reduced by the corresponding amount.

FASBI grew out of BI’s response to the recent Indonesian banking crisis (Ken-ward forthcoming). Beginning in September 1997, there was a massive drain on deposits in the troubled private banks as investors moved funds to the state banks. Even though the state banks ended up making larger losses, relative to their share of deposits, than the private banks, depositors correctly perceived that they were backed by implicit government guarantees. This transfer of deposits in late 1997 and early 1998 meant that the troubled private banks were experiencing an acute liquidity crisis at the same time that most state banks had excess liquid-ity. As a result, the interest rates paid by the strongest and weakest Indonesian banks on interbank loans regularly differed by more than 100 percentage points: while the strongest banks could borrow at 40–50%, the weakest had to pay 150% or more (Bank Indonesia 1999: 62).

BI responded to the switching of deposits from weak private banks to state banks by introducing the deposit facility that later became known as FASBI. This facility offered interest rates that were only slightly below the SBI rate in order to attract deposits from the strong banks to which depositors fled when they feared that weaker banks would fail. BI then lent these funds back to the weak banks in the form of resort loans. The enormous losses that resulted from BI’s last-resort lending during the crisis (Frécaut 2004) show that it cannot be justified in terms of the Bagehot-type recommendation that last-resort loans should be given freely against good collateral (Bagehot 1920: 164).

Since FASBI deposits are issued for shorter periods than SBI, but are also prom-ises by BI to pay fixed rupiah amounts, they are essentially the same as short-dated SBI. However, whereas SBI are issued at monthly auctions, the FASBI facility is permanently open and banks can deposit as much or as little as they wish at the rate set by BI, which at the time of writing is 7%. Because the banks are not rationed at the SBI auctions, or in deciding how much FASBI to hold, the two rates are never far apart. The one-month SBI rate is generally about 20 to 50 basis points (0.20 to 0.50 percentage points per year) above the FASBI rate, in compensation for the greater liquidity of FASBI, but the exact difference depends on expectations about changes in short-term interest rates.

The regulations that introduced FASBI provided for the possibility of BI offer-ing to accept deposits for terms of up to 14 days. In the event, BI has never accepted FASBI deposits for terms of more than seven days. It has usually offered seven-day deposits, and initially it also offered one-day deposits, with rates that varied according to whether the deposits were made in the morning or afternoon trading sessions. Before June 2004, the overnight FASBI rate set a floor on the overnight rate in the interbank money market, since banks would never lend to each other at a lower rate than that offered by BI. However, in June 2004, BI began to ration the amount of overnight FASBI that it would accept. The reason seems to have been its reluctance to pay interest on deposits whose maturities are so short that they do little to reduce the liquidity of the banking system. In January 2005, BI took this reasoning a step further and stopped accepting overnight FASBI altogether. The situation at the time of writing was that only seven-day FASBI were available, and there was no rationing of banks at the 7% rate set by BI.

If there were a deep secondary market in SBI, BI could trade in it to set one-week interest rates. In practice this market is thin, and BI therefore sets this inter-est rate directly using FASBI, which offers some extra flexibility that the SBI system does not possess. Of course the fact that BI operates in this way exacer-bates the thinness of the SBI secondary market.

Monetary Policy Techniques: Thailand

The BOT’s primary operating instrument is the 14-day repurchase, or ‘repo’, rate. The Monetary Policy Committee of the BOT meets about every six weeks to announce the Bank’s ‘policy rate’, which is its target for the 14-day repo rate. These announcements generally report the latest data on core inflation, and dis-cuss expected economic developments in the coming year. This background information is then used to justify the MPC’s choice of policy rate.

To implement the MPC’s decision, the BOT operates in two separate but closely connected repo markets, the bilateral market and the BOT-operated

ket. Trading in the bilateral market is usually conducted once or twice per fort-night. This trading involves the sale by the BOT, under repurchase agreements, of government securities to nine authorised dealers. The BOT indicates the amount of liquidity that it intends to absorb and invites tenders from these dealers at var-ious maturities, ranging from one day to one month. Recently, about half of the volume traded has been for one day and the next most important maturity is 14 days. Some trading takes place at seven days, but only very little is traded for one month. The BOT does not make a commitment on the total volume to be ten-dered. Rather, it adjusts this in the light of the bids to ensure that the average accepted rates are very close to the policy rate. In the case of the 14-day tenders, all bids must be at the policy rate, but bidders do not necessarily receive the full amount for which they bid. The BOT decides how much to accept and apportions the total among the dealers in proportion to their bids.

The BOT-operated repo market is open for one hour on each trading day. Between 40 and 50 institutions are eligible to bid in this market. These eligible institutions include large state-owned enterprises as well as banks and other financial institutions. Buy and sell bids are submitted to the BOT, which matches them and charges a small commission. As well as operating this market, the BOT trades in it on its own account, using it to absorb or inject whatever liquidity is needed to keep the 14-day rate close to the policy rate. The authorised dealers use the BOT-operated market to adjust the positions taken up in the bilateral market.

At the end of the day, banks with a shortage of liquidity can borrow from the BOT at the policy rate plus 1.5%, using government securities as collateral. Those with surplus liquidity can only leave it in their current accounts at the BOT. Since these accounts do not bear interest, banks try to operate on a very small margin of excess liquidity, and the bulk of the funds in their current accounts is there to satisfy statutory reserve requirements. The BOT does have provisions for allow-ing banks with current account deposits in excess of their statutory requirements to obtain a ‘credit’ against their future statutory requirements; that is, if they held more than the required amount of reserves in one month, they can hold less than the required amount in the next. Currently, the statutory reserve requirement is 1% of customers’ deposits. There is also a requirement that banks keep liquid assets of at least 6% of customers’ deposits. Liquid assets are defined to include current accounts at the BOT (although the required reserves are not really liquid), vault cash and government securities. At the time of writing, banks have large holdings of government securities and the demand for bank loans is low. As a result, the liquid assets requirement is not binding and banks hold well in excess of the 6% minimum.

Since lending to a central bank in its own currency is essentially risk-free, the BOT does not really need to provide collateral for its borrowings from the finan-cial system. Its reason for borrowing via repos, rather than employing a ‘pure borrowing’ facility like BI’s FASBI, is that the collateral that it provides to the institutions that lend to it can be used by these lenders as collateral for their own borrowing, if the need arises. This deepens the market in government paper and gives the lending institutions more flexibility than they would have if their lend-ing was in the form of a non-transferable term deposit at the BOT. This has the advantage for the BOT that financial institutions are willing to accept slightly

9BNM’s total holding of Malaysian government securities is less than 0.1% of its total assets.

lower interest rates than the BOT would have to pay if it simply offered term deposit facilities.

Although the bulk of the BOT’s open market operations are done in the repo market, it does sometimes purchase government securities outright. Since one of its long-term goals is to build up its portfolio of government securities, it does not generally engage in outright sales of them, and since most of its monetary oper-ations are intended to absorb liquidity rather than inject it, its outright purchases are infrequent and generally small. It can also use the swap market to affect domestic monetary conditions. For example, it can absorb domestic liquidity by swapping the foreign currency-denominated assets that it holds in international financial centres for baht.

Monetary Policy Techniques: Malaysia

BNM currently faces the problem of absorbing the large capital inflows that Malaysia is experiencing as a result of the widespread expectation that its tem-porarily fixed exchange rate may soon be revalued upwards relative to the dol-lar, and almost certainly will not be devalued in the near future. The special features of BNM’s monetary operations that distinguish them from those of BI and the BOT are due to the fact that it is constrained in the ways that it can absorb liquidity. BNM’s own holdings of Malaysian Government Treasury Bills (MGTBs) or other Malaysian government securities are too small to absorb more than a limited amount of the capital inflows of the recent past.9 Most of the

Malaysian government’s outstanding securities are held by ‘captive institu-tions’, such as insurance companies and the Employee Provident Fund (EPF), which are legally required to invest in government securities. At the same time, the Central Bank of Malaysia Act of 1958 fixes the maximum amount of BNM paper that can be issued relative to its capital, and this limit is now binding. As a result of this legal constraint, the Rgt 17 billion of Bank Negara paper now out-standing can be rolled over, but can only be increased in proportion to increases in BNM’s capital.

As a result of the constraints described above, BNM’s monetary operations mainly involve direct borrowing from the banks and other financial institutions in the form of deposits. Each morning, BNM announces a daily tender at which the banks bid for the right to place short-term deposits at BNM at rates that are usually very close to the ‘overnight policy rate’ (OPR). Much of this borrowing is overnight, but BNM also offers other maturities of up to a month. If the morn-ing tender turns out to have been too small to absorb all the liquidity in the mar-ket, a second tender is announced in the afternoon. BNM takes care not to over-tender, so it is very rare for there to be a shortage of liquidity.

In April 2004, as part of its ‘New Interest Rate Framework’, BNM eased direct controls on interest rates, abolished the ‘three-month intervention rate’ that had been used in the setting of interest rate ceilings on bank and finance company lending, and modified its operating procedures. The most important of the changes to the operating procedures are as follows.

10This overnight collateralised lending by BNM to a bank with a small deficit at the end of the day is quite different from last-resort lending to a bank in real financial difficulty. Last-resort lending would be made at much higher rates through a different facility.

• BNM would make more active use of repo operations in short-term monetary management. Since BNM does not have large holdings of MGTB and other government paper, its repo operations are normally done using securities that it first borrows from institutions such as the EPF and then sells, subject to repurchase agreements, to banks and other financial institutions.

• Short-term monetary management would focus on the overnight interbank interest rate, though BNM might also intervene at other maturities from time to time.

• BNM introduced the OPR, which was set at 2.7% and has so far remained unchanged. No trading actually takes place at this rate, but it does have two important functions. First, BNM announced that its day-to-day money market operations would aim to leave the overnight rate as close as possible to the OPR, which therefore provides a useful signal to market participants of the central bank’s intentions. Second, BNM stands ready to accept deposits at the end of each day’s trading at the OPR minus 25 basis points from banks with surplus liquidity, and to lend against collateral, in the form of Malaysian gov-ernment securities or Bank Negara paper, at the OPR plus 25 basis points to banks that end up short of funds at the end of the day.10With the OPR at 2.7%,

the overnight interbank rate is therefore sure to end up within a 50 basis point ‘overnight operating corridor’, centred on the OPR, with a floor at 2.45% and a ceiling at 2.95%.

Since the introduction of the New Interest Rate Framework, the weighted aver-age interest rate in overnight interbank trading has always been close to the OPR and has never reached either end of the operating corridor, though individual banks have occasionally made use of the facilities. In practice, monetary policy was not radically altered by the new framework, which mainly involves tidying up and formalising existing procedures. Some borrowing by BNM using repos has occurred, but it is still only a minor part of BNM’s total monetary operations, most of which still take the form of banks tendering for deposits in the way described earlier.

SIMILARITIES, DIFFERENCES AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

This survey has shown that BI, BOT and BNM have taken very similar approaches to the non-internationalisation of their currencies and the sterilisation of balance of payments effects on domestic monetary conditions. On the other hand, it has documented important differences among the countries and over time in their approaches to:

• the technical operating procedures of the central bank in the short-term money market; and

• the nominal variable to be targeted—base money, inflation or the exchange rate.

This final section summarises and attempts to appraise the various aspects of monetary and exchange rate policy of the three central banks. The appraisal inevitably rests on judgments that are somewhat subjective.

The Common Ground among the Three Central Banks

The uniformity of the three central banks’ approaches to the non-internationali-sation of their currencies is evidence that this policy is not likely to be changed in the near future. In the light of the disastrous experiences of all three countries in the Asian crisis, it is easy to understand this response, even though, as pointed out above, there are probably better and more direct alternatives that do not reduce the depth of the money market and the forward foreign exchange market. The ability of such a small country as New Zealand to weather the Asian crisis suggests that these policies can work, even in a world of high capital mobility. But they seem unlikely to be implemented in the foreseeable future in Indonesia, Thailand or Malaysia.

Similarly, the uniformity of the approaches to active intervention in the foreign exchange market, combined with sterilisation of the balance of payments effects on the domestic money supply, is evidence that this policy too is not likely to change soon. The sterilisation of balance of payments flows is much harder to jus-tify, since it is a major potential source of monetary instability. Thailand, in par-ticular, would probably have had a much less severe crisis in 1997 if the BOT had floated the currency much earlier, or if it had kept to the textbook rules of a fixed exchange rate system by holding NDA constant, or even contracting it, in the 12 months preceding July 1997, thus allowing the speculative pressure on the baht to trigger automatic stabilisers such as interest rate increases (Fane and McLeod 1999: 397–99). The sterilisation of the balance of payments outflow in this period meant that the BOT suddenly ran out of reserves before any of the automatic sta-bilisers had begun to operate.

Technical Operating Procedures

All three central banks peg short-term interest rates. Since they intervene heavily in the foreign exchange market they inevitably have to sterilise the effects on base money of these operations by offsetting interventions in the domestic money market. In the last few years, the day-to-day problem for all three central banks has usually been to absorb liquidity in the money market, so as to sterilise the liquidity created by their purchases of foreign exchange. If, as recommended in the preceding subsection, they intervened less actively in the foreign exchange market and allowed a much freer float of their currencies, this need for money market intervention would be greatly reduced. This is especially true for BNM, but is also true to a lesser extent for BI and the BOT.

The BOT’s short-term borrowing in the money market is done mainly by repo operations. BI borrows by issuing SBIs and operating a very short-term deposit facility, FASBI. BNM borrows mainly by attracting deposits, but has begun to put more emphasis on repo operations since the introduction of its New Interest Rate Framework. Central bank borrowing via repo operations has the advantage over borrowing by attracting term deposits that the collateral received by the commer-cial banks and other lenders to the central bank provides them with negotiable instruments against which they can borrow if the need arises. These lenders are

11When the ringgit was initially pegged in September 1998, Malaysia’s annual inflation was running at about 5.6% (month on 12 months earlier), and it took just under a year for the rate to fall below 2.5%. This lag in reducing inflation was presumably due to the grad-ual flow-through to non-traded prices of the large depreciation of the ringgit that had occurred in the year preceding September 1998.

therefore in a more liquid position than would be the case if they had placed term deposits at the central bank. This explains why BNM is trying to expand its use of repo operations, relative to its borrowing by attracting term deposits.

This survey has not been able to offer any explanation for the thinness of the secondary market for SBI, or for why BI does not encourage this market by con-ducting repo operations in SBI. Greater reliance on such repo operations would seem to be a sensible strategy for BI to pursue.

The Choice of Nominal Target

While there are some important differences across the three countries and over time, the apparent differences overstate the real ones. One reason for this is that, as illustrated by table 1, inflation and monetary growth are usually strongly cor-related. As a result of this correlation, there will often not be much difference between setting short-term interest rates so as to keep the rate of inflation within some medium-term target zone and setting them so as to keep the rate of growth of base money within a target zone that is obtained by adding the estimated rate of long-run GDP growth to the target zone for inflation.

The most obvious illustration of the similarity between targeting base money and targeting inflation is provided by the most dramatic monetary policy failure covered in this survey—BI’s failure to meet its base money targets in late 1997 and early 1998. To keep to its base money targets, BI obviously needed to sell SBI very much more aggressively than it actually did. If it had been following an inflation target, exactly the same response would have been called for.

Similarly, the long-runeffects of targeting inflation or base money will gener-ally not be very different from those of pegging the currency to that of a country that targets inflation. By pegging the ringgit to the dollar, Malaysia is assured of having the same medium-run rate of inflation of traded goods prices as the United States. While the US Federal Reserve does not have a formal, numerical inflation target, its deputy chairman has been quoted as saying that its policy in recent years has been to lean against disinflation when core inflation threatens to fall much below 1%, and, similarly, against inflation when the core rate threatens to rise above 2–2.5% (Berry 2004). This means that while its peg to the dollar remains in place, Malaysia’s medium-term inflation rate can only move outside the range of about 1–2.5% per year if its real exchange rate appreciates or depre-ciates substantially relative to that of the US.

Real exchange rate changes are of course possible, and the expectation of a nominal appreciation of the ringgit is, at the time of writing, generating capital inflows that could cause real appreciation. To date, however, the pegged exchange rate has given Malaysia low and stable inflation. Since August 1999, Malaysian inflation has remained between 1% and 2.5%, and since January 2000, it has remained between 1% and 2.1%.11If BNM had actually announced a policy of

tar-geting inflation, it could not have been criticised for failing to meet its target.

12The relative merits of targeting base money and inflation have been debated in this jour-nal by Grenville (2000a, 2000b) and Fane (2000a, 2000b).

Similarly, over the six-year period covered in table 1, Malaysia managed to pursue a relatively tight monetary policy despite not targeting base money, while Indo-nesia failed to do so, despite its stated commitment to base money targeting.

In the short run, the choice of nominal target is important. The advantage of allowing the exchange rate to float is that the induced movements in response to exogenous shifts in capital inflows and outflows help the economy adjust to these shifts without the need for large movements in domestic prices and nominal wages. That this is an important advantage in a world of volatile capital was con-firmed by the ability of Australia and New Zealand to survive the Asian crisis without any major calamity.

The choice between targeting inflation and targeting base money is less clear cut. The advantage of targeting base money is that it is something that the central bank can influence directly if it chooses to do so, whereas its ability to control inflation is much less direct and immediate. Targeting M0 therefore provides a way of sending a clear signal of the central bank’s determination—or lack of determination—to keep to its stated policy.12For this reason, the IMF was

proba-bly right to focus on M0 in designing monetary policies to restore confidence after the onset of the Asian crisis, and Indonesia paid the price for failing to follow these policies.

Targeting inflation is probably a better option if the central bank’s credibility is not at stake. If market participants are confident that long-run inflation will be kept within a narrow low range, a rise in interest rates becomes a clear signal of monetary tightening and not, as in Indonesia in late 1997 and early 1998, a sign that the central bank has lost control of the money supply and is in danger of lapsing into hyperinflation. Provided that the central bank’s credibility is not at stake, the advantage of targeting inflation, rather than base money, is that a slow steady growth in base money is at best a means to low and stable inflation, rather than an end in itself. Further, targeting base money will only be an effective means for achieving low and stable inflation if its velocity of circulation does not fluctuate in unpredictable ways. By targeting inflation, the central bank will auto-matically accommodate unexpected fluctuations in the velocity of circulation of base money. For this reason, the BOT’s decision to shift to inflation targeting, now that its credibility has largely been restored, was probably correct.

Whether it targets base money or inflation, the test for BI will continue to be whether it is willing and able to resist the political pressures to hold down inter-est rates even when the chosen variable is growing faster than the targeted rate. So far, BI’s record on sticking to temporarily unpopular strategies has not been as good as those of BNM and BOT.

REFERENCES

Alamsyah, Halim, Charles Joseph, Juda Agung and Doddy Zulverdy (2001), ‘Framework for Implementing Inflation Targeting in Indonesia’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Stud-ies37 (3): 309–24.

Athukorala, Prema-chandra (2001), Crisis and Recovery in Malaysia: The Role of Capital Con-trols, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham UK and Northampton MA.

Bagehot, W. (1920, 1st edition 1873), Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market, Mur-ray, London.

Bank Indonesia (1998), Report for the Financial Year 1997/98, Bank Indonesia, Jakarta. Bank Indonesia (1999), Report for the Financial Year 1998/99, Bank Indonesia, Jakarta. Bank Indonesia (2004), ‘Bank Indonesia Policy: A Low and Stable Inflation Rate’, online at

<www.bi.go.id>.

Bank Negara Malaysia (2004), ‘BNM Introduces New Interest Rate Framework’, online at <www.bnm.gov.my>.

Bank of Thailand (2000), ‘Exchange Rate Policy’, online at <www.bot.or.th>. Bank of Thailand (2004), ‘Monetary Policy Today’, online at <www.bot.or.th>.

Berry, John M. (2004), ‘Will Fed Keep Inflation Low When Greenspan Exits?’, online at <quote.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=10000039&refer=columnist_berry&sid=afQp yMEyKYmU>.

Djiwandono, J. Soedradjad (2004), ‘Liquidity Support during Indonesia’s Financial Crisis’,

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies40 (1): 59–76.

Fane, George, and Ross H. McLeod (1999), ‘Lessons for Monetary and Banking Policies from the 1997–98 Economic Crises in Indonesia and Thailand’, Journal of Asian Econom-ics10: 395–413.

Fane, George (2000a), ‘Indonesian Monetary Policy during the 1997–98 Crisis: A Mone-tarist Perspective’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies36 (3): 49–64.

Fane, George (2000b), ‘Indonesian Monetary Policy: A Rejoinder’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies36 (3): 71–2.

Frécaut, Olivier (2004), ‘Indonesia’s Banking Crisis: A New Perspective on $50 Billion of Losses’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies40 (1): 37–57.

Grenville, Stephen (2000a), ‘Monetary Policy and the Exchange Rate during the Crisis’,

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies36 (2): 43–60.

Grenville, Stephen (2000b), ‘Indonesian Monetary Policy: A Comment’, Bulletin of Indo-nesian Economic Studies36 (3): 65–70.

Kenward, Lloyd (forthcoming), ‘New Financial Instruments and Their Implications for Monetary Policy’, in Anwar Nasution (ed.), Indonesia’s Economy after the Crisis: Economic Policy under Democracy, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore.

McLeod, Ross H. (2003), ‘Towards Improved Monetary Policy in Indonesia’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies39 (3): 303–24.