www.elsevier.comrlocaterapplanim

Discriminating among novel foods: effects of

energy provision on preferences of lambs for

poor-quality foods

Juan J. Villalba

), Frederick D. Provenza

Department of Rangeland Resources, Utah State UniÕersity, Logan, UT 84322-5230, USA

Accepted 17 June 1999

Abstract

Our objective was to better understand how lambs discriminate among novel foods based on flavor and post-ingestive effects. We first determined how temporal sequence of food ingestion

Ž

and post-ingestive feedback affected preference when lambs were fed flavored wheat straw a

. Ž .

poorly nutritious novel food immediately after eating milo grain an energy-rich novel food , or after milo was infused in the rumen. Lambs did not acquire a preference for flavored straw when

Ž .

they were fed straw immediately after eating milo P).10 , evidently because they quickly discriminated the flavor-feedback effects of milo from straw. However, lambs infused with milo prior to eating straw in one flavor or another preferred the flavored straw eaten after the milo

Ž .

infusions P-0.001 , and they preferred milo)flavored straw eaten after milo infusions)

Ž . Ž .

flavored straw eaten without milo infusions P-0.001 . Thus, when the flavor cue milo was removed, lambs did not discriminate milo from straw to as great a degree as when they first ate milo and then ate straw. We next attempted to better understand how lambs quickly discriminated

Ž . Ž .

between novel foods — grape pomace–starch 70–30% and grape pomace–cellulose 70–30% — that differ in digestible energy content. Lambs preferred pomace–starch from first exposure

ŽP-0.001 , and we hypothesized that they generalized a preference from eating familiar foods.

like barley and milo that are about 80% starch to the novel grape pomace–starch mixture. To test

Ž .

this hypothesis, we gave lambs a toxin LiCl dose after they ate milo, and then measured their preference for pomace–starch. Intake of pomace–starch was lower in the Milo–LiCl group than in

Ž .

controls that received only LiCl P-0.001 , which is consistent with the hypothesis that lambs

Ž . Ž .

generalized a preference from familiar foods barley and milo to a novel food pomace–starch . Finally, we determined how duration and amount of exposure to two novel foods — grape

Ž . Ž .

pomace–starch 70–30 and grape pomace 100 — influenced preference. When both foods were offered for only 20 minrday, intake of pomace and pomace–starch did not differ on day 1 to 8,

)Corresponding author. Tel.:q1-435-797-2539; fax:q1-435-797-3796; E-mail: [email protected]

0168-1591r00r$ - see front matterq2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Ž .

Ž .

and pomace was preferred to pomace–starch during day 9 to 15 P-0.05 . This pattern quickly reversed — pomace–starch became preferred to pomace — when the foods were offered for 8

Ž .

hrday for the next 6 days P-0.001 . These findings suggest that energy deprivation and the amount of food ingested both affected how quickly lambs discriminated between foods that differed in energy, and that lambs needed to eat a threshold amount of an energy-rich novel food before they acquired a preference for that food.q2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Preferences; Starch; Energy; Supplementation; Experience; Lambs

1. Introduction

Energy supplementation can increase or decrease forage intake, depending on the Ž

kind and amount of supplement consumed and the availability of nitrogen reviewed by

. Ž

Caton and Dhuyvetter, 1997 . Low levels of grain supplementation Henning et al.,

. Ž .

1980 , or low doses of starch infused into the rumen Villalba and Provenza, 1997a , increase roughage intake by sheep. Supplementation with energy increases byproducts of

Ž .

fermentation like volatile fatty acids VFA , which at low doses condition preferences in

Ž .

sheep Villalba and Provenza, 1996, 1997b . Likewise, sheep prefer poor-quality foods, or non-nutritive flavors in solutions, associated with intraruminal infusions of glucose ŽBurritt and Provenza, 1992; Ralphs et al., 1995 or starch Villalba and Provenza,. Ž

. 1997a, 1999 .

Given that byproducts of energy fermentation condition preferences, it is conceivable that ruminants may acquire preferences for poor-quality foods like straw, if straw ingestion coincides with increased VFA production due to eating an energy-rich supplement just prior to eating the straw. If the effects of VFA from grain supplementa-tion condisupplementa-tion preferences for poor-quality foods, strategic supplementasupplementa-tion could en-hance preference for plant species of lesser nutritional quality. On the other hand, ruminants may quickly discriminate the flavor-post-ingestive effects of the supplement from the poor-quality food, in which case they would not acquire a preference for the poor-quality food.

Our objective was to better understand how lambs discriminate among novel foods based on flavor and post-ingestive effects, and to determine if energy supplementation affected the preferences of lambs for a poorly nutritious food. We first determined how temporal order of food ingestion and post-ingestive feedback affected preference when

Ž .

lambs were fed a poorly nutritious food straw immediately after eating an energy-rich

Ž .

food milo , and when lambs were fed straw after an infusion of milo into the rumen. We then determined how lambs discriminated which of two novel foods was highest in energy.

2. Materials and methods

All experiments were conducted at the Green Canyon Ecology Center, located at Ž

.

crossbreds of both sexes were individually penned and had free access to mineral

Ž .

blocks and fresh water. Alfalfa Medicago satiÕa pellets were the basal diet in all experiments.

2.1. Experiment 1

Ž .

The objective of this experiment was to determine 1 if lambs preferred flavored

Ž .

wheat Triticum aestiÕum straw, a poorly nutritious food, when its consumption

Ž .

followed ingestion or intraruminal infusions of milo Sorghum bicolor subglabrescens , Ž .

an energy-rich supplement, and 2 if previous experience with these foods affected preference. We conducted four trials. The same animals and flavor–nutrient associations were maintained during trials 1 to 3. A new set of animals was used in Trial 4.

2.1.1. Trial 1

The objective of this trial was to determine if lambs acquired a preference for flavored wheat straw eaten immediately after they ate milo and if familiarity with these foods affected preference.

2.1.1.1. Initial exposure to straw and milo. Straw and milo were novel foods for all

lambs, and our objective was to maintain this condition as much as possible, but at the same time increase the likelihood that all lambs would consume some straw and milo

Ž .

during conditioning. Each day at 0800 h, lambs 28 kg BW were offered 25 g of straw Ž1–2 cm particle size . At 0900 h, orts were collected and weighed. When a lamb. consumed G20 g of straw on 1 day, exposure to straw ended for that lamb. Exposure also ended when the cumulative intake of straw wasG20 g for a lamb. After 9 days, all

Ž . Ž .

lambs had reached the first ns10 or the second ns14 criterion. On average, lambs

Ž .

ate a cumulative amount of 31 g of straw SEMs1 throughout the 9-days period. After exposure to straw, lambs had access to alfalfa pellets from 1200 h to 1700 h. At

Ž .

1500 h, lambs were offered 100 g of milo whole grain . At 1600 h, orts were collected and weighed. When a lamb consumedG50 g of milo 1 day, exposure to milo ended for that lamb. Exposure also ended when the cumulative intake of milo was G50 g. After 6

Ž . Ž .

days, all lambs had reached the first ns16 or the second ns8 criterion. On

Ž .

average, lambs consumed a cumulative amount of 82 g of milo SEMs1 during the 6-days period. Five lambs consumed all 100 g of milo offered in 1 day.

After initial exposure to straw and milo, lambs were randomly divided in two groups Ž12 lambsrgroup . Lambs in Group 1 naive group received no more exposure to straw. Ž .

Ž .

or milo until conditioning, whereas lambs in Group 2 experienced group received more

Ž .

exposure to straw and milo described below . During initial exposure, cumulative

Ž .

intake for lambs in Groups 1 and 2 was 29 g and 34 g SEMs1 of straw, and 84 g and

Ž .

81 g SEMs2 of milo, respectively.

2.1.1.2. Familiarization with straw and milo. From 0800 h to 1000 h, lambs in Group 2

were offered coconut-flavored straw on even days and onion-flavored straw on odd

Ž . Ž .

Ž .

straw at a concentration of 2% wrw . Every day at 1500 h, lambs in Group 2 were offered 200 g of milo; orts were collected at 1700. Exposure to flavored straw and milo

Ž .

lasted for 8 days. Lambs consumed 35 grday SEMs4 of coconut-flavored straw, 35

Ž . Ž .

grday SEMs4 of onion-flavored straw, and 136 grday SEMs8 of milo. All lambs had access to alfalfa pellets from 1200 h to 1700 h.

2.1.1.3. Initial preference test. After the familiarization period, lambs in Groups 1 and 2

received coconut- and onion-flavored straw simultaneously for 15 min, and intake and preference for each flavor were determined. After the preference test, lambs in each group were sorted in decreasing order by preference for coconut, and pairs of lambs Žfrom high to low preference. were randomly assigned to receive that flavor in association with milo during conditioning. Thus, differences due to initial flavor preferences were balanced.

2.1.1.4. Conditioning. On even days at 0800 h, all lambs had access to 200 g of milo for

Ž .

5 min Table 1 . Immediately after milo ingestion, half of the lambs in each group were offered coconut-flavored straw and the other half were offered onion-flavored straw for

Ž .

30 min Treatment 1 . All lambs had alfalfa pellets from 1200 h to 1700 h; no food was offered until the next day. On odd days, straw was offered to all animals but the flavors

Ž .

were switched so that lambs that received coconut- onion- flavored straw on even days

Ž .

received onion- coconut- flavored straw on odd days. During odd days, no milo was

Ž . Ž

fed before straw consumption Treatment 2 . Instead, 200 g of barley Hordeum

.

Õulgare grain was fed at 1600 h for 5 min.

The amount of straw fed on even days was equal to a lamb’s intake of straw the previous day, which controlled for amount of exposure to the flavored straw. Lambs in

Ž . Ž .

Groups 1 and 2 consumed, respectively, 26 SEMs3 and 22 grday SEMs2 of

Ž . Ž .

flavored straw, and 188 SEMs4 and 176 grday SEMs7 of milo during even

Ž . Ž .

days; they ate 28 grday SEMs3 and 21 grday SEMs3 of flavored straw during odd days.

Ž .

2.1.1.5. Preference test. After 8 days of conditioning four even and four odd , lambs

Ž .

were offered coconut- and onion-flavored straw simultaneously for 15 min Table 1 . Milo was not provided before the preference test. We determined intake of each food.

2.1.2. Trial 2

Trial 2 determined if restricting the supply of energy from the basal diet increased preference for flavored straw eaten after milo consumption. Conditioning was the same as for Trial 1, but alfalfa pellets were restricted to 1100 g lamby1 dayy1, which supplied

Ž .

about 80% of their digestible energy requirements NRC, 1985 . Barley was not offered

Ž .

on odd days. Lambs in Groups 1 and 2 ate 62 grday and 52 grday SEMs4 of flavored straw, and all 200 g of milo on even days. They ate 58 grday and 49 grday ŽSEMs3 of flavored straw on odd days..

Lambs were tested for preference as in Trial 1. On the following day, all lambs received coconut- and onion-flavored straw as well as milo simultaneously for 5 min.

Ž .

Table 1

Methods and procedures in Experiment 1

Group Experience with straw and milo before conditioning

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Trials 1, 2, 3 same animals 1 Naive Limited G20 g straw;G50 g milo

Ž .

2 Experienced 8 days of exposure to flavored straw and

Ž .

milo 2 hrday

Ž .

Trial 4 1 Naive None

Ž .

2 Experienced 8 days of exposure to flavored straw and

Ž .

Even-numbered days: Milo followed by flavored straw Flavor 1

Ž .

Odd-numbered days: Flavored straw only Flavor 2 Preference test

Ž .

Choice of flavored straw Flavors 1 and 2 b

Trial 2

Ž .

Conditioning 8 days Same as described for Trial 1 Preference test

Ž .

Day 1: Choice of flavored straw Flavors 1 and 2

Ž .

Day 2: Choice of milo and flavored straw Flavors 1 and 2 b

Trial 3

Ž .

Conditioning 8 days

Ž .

Even-numbered days: Intraruminal infusions of milo followed by flavored straw Flavor 1

Ž .

Odd-numbered days: Flavored straw only Flavor 2 Preference test

Ž .

Day 1: Choice of flavored straw Flavors 1 and 2

Ž .

Day 2: Choice of milo and flavored straw Flavors 1 and 2 b

Trial 4

Ž .

Conditioning 8 days Same as described for Trial 1 Preference test: Milo–LiCl and Control

Ž .

Choice of flavored straw Flavors 1 and 2

a Ž .

Basal diets: Free access to alfalfa pellets 5 hrday , and 200 g barley grain during odd-numbered days. b

Alfalfa pellets restricted to supply 80% digestible energy lamby1 dayy1.

2.1.3. Trial 3

The objective of Trial 3 was to determine lambs’ preference for flavored straw eaten after an infusion of milo into the rumen, rather than after eating milo. Conditioning was the same as for Trial 2, but lambs were given intraruminal infusions of milo by oral

Ž .

intubation rather than fed milo Table 1 . The milo suspension was prepared by grinding milo through a 0.5-mm screen and then mixing it with tap water at room temperature. To prevent sudden changes in the rumen environment, the level of milo infused

Ž . Ž .

during the last two infusions. Lambs in Groups 1 and 2 consumed, respectively, 82

Ž . Ž .

grday SEMs3 and 73 grday SEMs3 of flavored straw on even days, and 77

Ž . Ž .

grday SEMs4 and 68 grday SEMs5 on odd days. Lambs were tested for

Ž .

preference as in Trial 2 Table 1 .

2.1.3.1. Effects of milo on alfalfa intake. To determine if milo infusions affected

subsequent food intake, all lambs were offered the following at 0800 h for 3 days: Day 1

Ž .

— Milo 200 g and 5 min later free access to alfalfa pellets for 1 h; Day 2 — Free

Ž .

access to alfalfa for 1 h; Day 3 — Milo 200 g by oral intubation and 5 min later free access to alfalfa pellets for 1 h.

2.1.4. Trial 4

The objective of Trial 4 was to determine if the complete lack of experience with flavored straw and milo affected the acquisition of a preference for flavored straw when straw ingestion immediately followed milo ingestion.

Ž .

A new group of 24 lambs 31 kg BW was presented on day 1 with milo and straw in temporal association as described in the Conditioning section of Trial 1. Based on day 1 intake, and a criterion of ingesting more than 5 g of milo and straw, 12 lambs were

Ž .

placed in Group 1 naive group . The rest of the lambs were placed in Group 2 Žexperienced lambs . On day 1 of exposure, lambs in Group 1 ate 45 g SEMs. Ž 11 of.

Ž . Ž .

milo and 25 g SEMs7 of flavored straw. Lambs in Group 2 ate 10 g SEMs2 of

Ž .

milo and 8 g SEMs3 of flavored straw.

After day 1, lambs in Group 1 received no additional exposure to straw or milo. Lambs in Group 2 received more extensive experience with coconut- and onion-flavored straw and milo, as described for Trial 1. During this familiarization period, lambs in

Ž . Ž .

Group 2 ate 23 grday SEMs4 of coconut-flavored straw, 16 grday SEMs2 of

Ž .

onion-flavored straw, and 188 grday SEMs4 of milo. After familiarization, lambs in Group 2 were tested for preference and assigned to receive coconut-flavored straw in association with milo as described for Trial 1.

Ž .

Lambs in Groups 1 and 2 were conditioned as described for Trial 2 Table 1 . To be consistent with Trial 3, milo was offered in ground form in amounts similar to those infused on successive even days in Trial 3: 100, 150, 200, and 200 g. Lambs in Groups

Ž . Ž .

1 and 2 consumed, respectively, 42 SEMs5 and 28 grday SEMs5 of flavored

Ž . Ž .

straw on even days, and 33 grday SEMs5 and 37 grday SEMs6 on odd days. Preference tests were conducted as described for Trial 1.

2.2. Experiment 2

The objective of this experiment was to determine if lambs discriminated between the post-ingestive effects of novel foods of different energy densities when the foods were offered simultaneously, and if they generalized preferences based on past experiences with the oral and post-ingestive effects of starch-containing foods. Lambs in all trials received alfalfa pellets at 1200 h as their basal diet to provide about 80% of their daily

Ž .

2.2.1. Trial 1

Ž .

2.2.1.1. Exposure to noÕel foods and preference tests. Lambs 32 kg BW from

Ž .

Experiment 1 Trials 1–3 were randomly divided into two groups. The test foods and flavors used in Experiment 2 were different from those used in Experiment 1 and we applied the same level of food restriction in both experiments. Thus, carryover effects from Experiment 1 were minimized.

Ž .

At 0800 h, all lambs were offered two novel foods simultaneously: 1 a 70–30 Žwrw mixture of grape pomace — a low-quality food 4.6 MJrkg DE; 1.6% DP;. Ž

. Ž .

NRC, 1985 — and starch; and 2 a 70–30 mixture of grape pomace and a-cellulose.

Ž .

Different flavors Apple and Maple; Agrimerica were added to the foods at a

concentra-Ž .

tion of 2% wrw to facilitate discrimination. Group 1 received the maple-flavored pomace–starch mixture and the apple-flavored pomace–cellulose mixture. Group 2 received the opposite flavorrnutrient associations.

Ž .

On the first day test 1 , the foods were offered for 5 min. During the next 3 days Žtests 2 to 4 , exposure was extended to 20 min. The aim of the 5 min exposure was to. determine if lambs discriminated quickly between the two novel foods. Refusals of the

Ž .

foods were collected and intake of each food was calculated Table 2 .

2.2.1.2. Exposure to the cellulose–pomace mix and preference tests. Preference for the

pomace–starch mix was nearly absolute, and thus after test 4, all lambs were exposed for 20 minrday for 2 days to only the pomace–cellulose mix in order to compensate for the increased experience they were having with the pomace–starch mix. Lambs

con-Ž .

sumed an average of 49 g SEMs8 of the pomace–cellulose mix.

After exposure to pomace–cellulose, all lambs were again offered a choice of the two

Ž .

foods test 5 . Again, preference for the pomace–starch mix was nearly absolute, so lambs were exposed to the pomace–cellulose mix for another 20 minrday for 4 days.

Ž .

Lambs ate an average of 51 g SEMs6 of the pomace–cellulose mix. After this

Ž .

exposure, the cumulative average intake of the pomace–starch mix 355 g was similar

Ž .

to the cumulative average intake of the pomace–cellulose mix 329 g , and lambs were

Ž .

again offered a choice of the two foods test 6; Table 2 .

2.2.2. Trial 2

The objective of this trial was to determine if lambs generalized an aversion from a

Ž . Ž .

familiar grain milo to a novel food pomace that contained starch. All lambs in Trial 1 preferred pomace–starch over pomace–cellulose from the first preference test. We hypothesized the preference for pomace–starch could be due to lambs generalizing from

Ž .

familiar foods like grains, which are high in starch about 80% , to novel foods that contain starch.

After test 6, lambs in each group were sorted in decreasing order of preference for pomace–starch. Pairs of lambs were then randomly assigned to two new groups, LiCl–Milo and Control, to balance preference for the pomace–starch and pomace–cel-lulose between groups.

The day after test 6, lambs in the LiCl–Milo group were offered milo from 0800 h

Ž . Ž .

Table 2

Methods and procedures in Experiment 2 b

Trial 1

Novel foods Group 1 Group 2

grape pomace– qmaple flavor qapple flavor

Ž .

starch 70–30

grape pomace–a- qapple flavor qmaple flavor

Ž .

cellulose 70–30

Days Event

1–4; 7; 12 Choice of flavored grape pomace–starch and flavored grape pomace–a-cellulose 5 minr

Ž . Ž .

day day 1 ; 20 minrday days 2–4; 7; 12 . 5–6; 8–11 Exposure to flavored pomace–a-cellulose

Ž .

without choice 20 minrday . a

Trial 2

New groups from Trial 1 Milo ingestion before LiCl LiCl infusions

LiCl–Milo group YES YES

Control NO YES

Ž .

Day Event after LiCl infusions

1 LiCl–Milo group receives Milo

2 Choice of flavored grape pomace–starch

Ž70–30 and flavored grape.

Ž .

Even-numbered days: infusions ofa-celluloseqflavored grape pomace Flavor 1

Ž .

Odd-numbered days: flavored grape pomace only Flavor 2 Preference test

Ž .

Choice of flavored grape pomace Flavors 1 and 2 b

Trial 4

Ž . Ž .

Novel foods: grape pomace–starch 70–30 and grape pomace 100 Period 1

Ž .

Days 1–15 Choice of grape pomace–starch and grape pomace 20 minrday Period 2

Ž .

Days 1–6 Choice of grape pomace–starch and grape pomace 8 hrday

Ž .

Ž .

Table 2 continued a

Trial 5

New Groups from Trial 4 Milo ingestion before LiCl LiCl infusions

LiCl–Milo group YES YES

Control NO YES

Ž .

Day Event after LiCl infusions

1 LiCl–Milo group receives Milo

2 Choice of pomace–starch and grape pomace

3 LiCl–Milo and Control Groups receive Milo

a Ž .

Basal diets: Free access to alfalfa pellets 5 hrday . b

Alfalfa pellets restricted to supply 80% digestible energy lamby1 dayy1.

lambs in the LiCl–Milo and Control groups received by oral intubation 200 ml of a solution containing 300 mgrkg BW of LiCl, a dose that causes strong food aversions in

Ž .

sheep duToit et al., 1991 . On day 2, lambs in the LiCl–Milo group were fed milo from 0800 h to 0815 h, but no lambs ate.

On day 3, we determined if lambs generalized the aversion from milo to pomace–

Ž . Ž .

starch by measuring intake of pomace–starch 70–30 and pomace–cellulose 70–30 from 0800 h to 0815 h. On day 4, lambs were offered milo from 0800 h to 0815 h to

Ž Ž .

determine if the aversion to milo persisted milo intake was 3 g SEMs1 in the

Ž . .

LiCl–Milo group and 421 g SEMs13 in the Control group . On day 5, we altered the pomace–starch mix to 30–70, and offered lambs a choice between the pomace–starch

Ž .

and pomace–cellulose from 0800 h to 0815 h Table 2 .

2.2.3. Trial 3

Lambs displayed low preferences for the pomace–cellulose mix throughout Trial 1. The objective of Trial 3 was to determine if this was due mainly to oral or post-ingestive effects.

2.2.3.1. Initial preference test. We measured intake of forage- and anise-flavored grape

Ž .

pomace offered simultaneously to 24 lambs 32 kg BW for 20 min. The flavors ŽAgrimerica , which were novel for the lambs, were mixed with pomace at a concentra-.

Ž .

tion of 2% wrw . Lambs were sorted in decreasing order by initial preference for anise,

Ž .

and pairs of lambs were randomly assigned to two groups 12 lambsrgroup so that the groups were balanced according to initial flavor preference.

2.2.3.2. Conditioning. Lambs were conditioned during 20 minrday using the same conditioning paradigm described in Experiment 1. Flavored grape pomace replaced flavored straw and cellulose replaced milo in the infusions. Cellulose infusions were given immediately after lambs began to eat flavored grape pomace. The cellulose suspension was prepared mixing 250 ml tap water and 20 g of cellulose. This amount of cellulose was the maximum amount of the pomace–cellulose mix that lambs ingested

Ž .

Ž .

grday SEMs5 when flavored pomace was not paired with cellulose, and 163 grday ŽSEMs5 when flavored pomace was paired with cellulose..

Lambs were tested for preference during 20 min, as described for Experiment 1 ŽTable 2 ..

2.2.4. Trial 4

The objective of this trial was to determine if duration of exposure influenced Ž preference for grape pomace–starch relative to grape pomace. From days 1 to 15 Period

. Ž . Ž .

1 , lambs 35 kg BW from Experiment 1 Trial 4 were offered two novel foods — a 70–30 mixture of grape pomace–starch and grape pomace — simultaneously from 0800 h to 0820 h. Refusals were collected and intake of each food was calculated.

Ž .

From days 16 to 21 Period 2 , lambs were offered 500 g of each food described Ž above, but the amount of exposure was increased to from 20 minrday to 8 hrday 0800

.

h to 1600 h daily . At 1600 h, refusals were collected and weighed and lambs received 1500 g of alfalfa pellets.

On day 22, lambs were offer both foods for only 20 min. Intake of each food was

Ž .

recorded and compared with the last day of Period 1 Table 2 .

2.2.5. Trial 5

The objective of this trial was to determine if lambs generalized an aversion from a grain high in starch to another food that contained starch. After Trial 4, lambs were

Ž .

treated with LiCl as described for Trial 2; lambs consumed 372 g SEMs51 of milo prior to receiving LiCl, and no milo following the LiCl infusion. After LiCl infusions,

Ž .

lambs in the LiCl–Milo group did not eat milo, whereas Controls ate 363 g SEMs32 .

3. Statistical analyses

3.1. Experiment 1

Food intake during preference tests was analyzed as a split-plot design with animals

Ž .

nested within group naive and experienced . Group was the between-subject factor and

Ž w x w

treatment received during conditioning 1 milo supplementation or 2 no supplementa-x.

tion was the within-subject factor. Alfalfa intake was analyzed as a repeated measures

Ž .

design; daily days 1, 2, 3 intake was the repeated measure. Means were compared with LSD tests.

3.2. Experiment 2

Food intake in Trials 1–3 and 5 was analyzed as a split-plot with lambs nested within

Ž w x w x.

groups. Group 1 or 2 Trials 1 and 3 ; LiCl–Milo or Control Trials 2 and 5 was the

Ž .

between-subject factor; test foods pomace–starch; pomace–cellulose; Trials 1 and 2 , Ž

period preference test before LiCl administration; preference test after LiCl

administra-. Ž

tion; Trials 2 and 5 and treatment received during conditioning cellulose infusions; no .

Food intake in Trial 4 was analyzed as a split-plot design. Lambs and test foods Žpomace–starch; pomace were whole-plot factors and day repeated measure was the. Ž . sub-plot. Intake of the test foods during the last day of Period 1, and the day after Period 2, was analyzed as a split-plot with lambs and test foods as the whole plot and day as the sub-plot.

4. Results

4.1. Experiment 1

4.1.1. Trial 1

The objective of this trial was to determine if lambs acquired a preference for

Ž .

flavored straw eaten immediately after they ate an energy supplement milo . Lambs did not differ in initial preference for the flavors to be associated with milo during

Ž . Ž .

conditioning: 12 vs. 11 g experienced group and 12 vs. 10 g naive group for

Ž .

treatments 1 and 2, respectively P).05; SEMs3 . Similarly, no preference was

Ž .

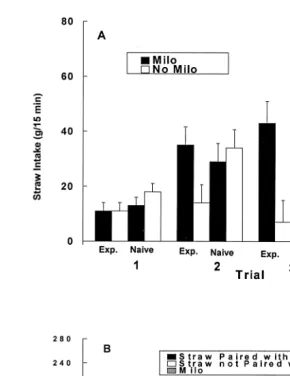

evident after conditioning with milo Fig. 1A, Trial 1 , as reflected in non-significant

Ž .

treatment and group by treatment effects P)0.05 .

4.1.2. Trial 2

The objective of this trial was to determine if restricting the supply of energy from the basal diet increased preference for flavored straw eaten after lambs consumed milo. Lambs in the experienced group preferred the flavored straw consumed after milo

Ž .

ingestion Fig. 1A, Trial 2; treatment by group interaction P-0.1 . When lambs were offered milo along with the flavored straw in the second preference test, they strongly

Ž

preferred milo to flavored straw 194 g vs. 5 g and 4 g for milo, flavored straw paired with milo, and flavored straw not paired with milo, respectively, P-0.001; Fig. 1B,

. Ž

Trial 2 . Preferences did not differ between groups group and treatment by group .

interaction; P)0.05 .

4.1.3. Trial 3

This trial determined lambs’ preference for flavored straw eaten after an infusion of milo into the rumen, rather than after eating milo. Lambs strongly preferred the flavored

Ž

straw paired with intraruminal infusions of milo 46 g vs. 10 g for Treatments 1 and 2, .

respectively, P-0.001, SEMs5.77 , and preferences did not differ between groups Žgroup effect and treatment by group interaction; P)0.05; Fig. 1A, Trial 3 . When. lambs received milo and flavored straw in the second preference test, they preferred

Ž

milo)flavored straw paired with milo)flavored straw not paired with milo 197 g vs. .

16 g and 3 g, respectively, P-0.001; Fig. 1 B, Trial 3 . Preferences did not differ

Ž .

between groups group effect and treatment by group interaction; P)0.05 . Ž

Prior ingestion of milo affected intake of alfalfa. Intake of alfalfa during a 1-h .

period was higher after lambs ate 200 g of milo, or received 200 g of milo by infusion, Ž

than when no milo was offered: 799, 797, and 688 g, respectively P-0.001; .

Ž . Ž .

Fig. 1. Experiment 1. A Mean"SEM intake of flavored straw by lambs during preference tests after four

Ž . Ž . Ž

conditioning periods. During conditioning even days milo was ingested Trials 1, 2 and 4 or infused Trial

.

3 into the rumen before straw consumption. One group of lambs had previous experience with straw and milo

ŽExp. , and another group had moderate Trial 1 or no Trial 4 experience Naive with those foods before. Ž . Ž . Ž .

Ž . Ž . Ž .

conditioning. Means differed only for Exp. Trial 2 P-0.1 . B Mean"SEM intake of flavored straw and

Ž .

milo by lambs during two preference tests conducted after Trials 2 and 3. During conditioning even days ,

Ž . Ž .

milo was ingested Trial 2 or infused Trial 3 into the rumen before straw consumption. One group of lambs

Ž . Ž .

had experience with straw and milo Exp. , and another group had less experience with those foods Naive

Ž .

before conditioning. Milo intake was higher than straw intake in both trials P-0.001 , and preference of

Ž .

flavored straw paired with milo)flavored straw not paired with milo in Trial 3 P-0.001 .

4.1.4. Trial 4

Ž . Ž . Ž .

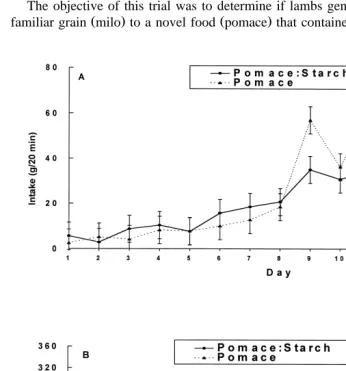

Fig. 2. Experiment 2 Trial 1 . Mean"SEM intake of pomace–starch and pomace–cellulose 70–30 when

Ž .

both foods were novel to all lambs. Means differed for all days P-0.001 .

straw ingestion immediately followed milo ingestion. No preference was found after

Ž .

conditioning with milo Fig. 1A, Trial 4 , as reflected in non-significant treatment or

Ž .

group by treatment effects P)0.05 .

4.2. Experiment 2

4.2.1. Trial 1

This trial determined if lambs discriminated between novel foods of different energy densities. Lambs strongly preferred the pomace–starch to the pomace–cellulose mixture

Ž . Ž .

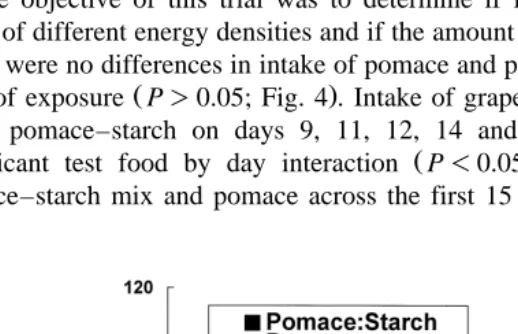

Fig. 3. Experiment 2 Trial 2 . Mean"SEM intake of pomace–starch and pomace–cellulose before and after

Ž .

LiCl was administered 300 mgrkg BW to two groups of lambs. The Milo–LiCl group received milo before

Ž .

LiCl infusions whereas the Control group received only LiCl. Intake of pomace–starch differed P-0.001

Ž .

Ž81 g vs. 5 g, respectively; P-0.001; SEMs5 . This preference was evident from the. first day of exposure and increased throughout days, as evidenced by a significant test

Ž .

food by day interaction P-0.001; Fig. 2 . Preferences did not differ between groups Žgroup and test food by group effects P)0.05 ..

4.2.2. Trial 2

The objective of this trial was to determine if lambs generalized an aversion from a

Ž . Ž .

familiar grain milo to a novel food pomace that contained starch. After pairing milo

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Fig. 4. Experiment 2 Trial 4 . A Mean"SEM intake of pomace–starch 70–30 and pomace by lambs. Both foods were offered for 20 minrday and they were both novel to all lambs. Means differed on days 9, 11,

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

12, 14 and 15 P-0.001 . B Mean"SEM intake of pomace–starch 70–30 and pomace by lambs. Both

Ž .

with LiCl, lambs still preferred pomace–starch to pomace–cellulose, but the pattern of

Ž .

preference changed group by food by period interaction; P-0.05; Fig. 3 . Intake of

Ž .

the pomace–starch mix decreased in both groups after the LiCl treatment P-0.001 , but intake of pomace–starch was lower for lambs in the Milo–LiCl group than for lambs

Ž .

in the Control group P-0.001; Fig. 3 .

When the proportion of starch was increased from 70–30 to 30–70 in the pomace–

Ž .

starch mix, no differences were found in the intake of the test foods P)0.05; Fig. 3 . Ž

Preferences did not differ between groups group and test food by group effects; .

P)0.05 .

4.2.3. Trial 3

The objective of this trial was to determine if low preferences for pomace–cellulose mix were due mainly to the oral or to the post-ingestive effects of cellulose. Lambs did not differ in preference for flavored pomace prior to conditioning: 47 g vs. 45 g for

Ž .

Treatments 1 and 2, respectively P).05; SEMs9 . Cellulose conditioning did not Ž

affect the development of preferences for flavored pomace 72 g vs. 84 g for Treatments .

1 and 2, respectively; P)0.05; SEMs12 .

4.2.4. Trial 4

The objective of this trial was to determine if lambs discriminated between novel foods of different energy densities and if the amount of exposure affected their response. There were no differences in intake of pomace and pomace–starch mix during the first 8

Ž .

days of exposure P)0.05; Fig. 4 . Intake of grape pomace was higher than intake of

Ž .

grape pomace–starch on days 9, 11, 12, 14 and 15 P-0.001 , which caused a

Ž .

significant test food by day interaction P-0.05; Fig. 4 . Average intake of the Ž

pomace–starch mix and pomace across the first 15 days did not differ 24 g vs. 31 g,

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Fig. 5. Experiment 2 Trial 4 . Mean"SEM intake of pomace–starch 70–30 and pomace by lambs on the

Ž . Ž .

last day of 20-min exposures Period 1 and after 8-h exposures Period 2 . Mean intake decreased for pomace

Ž .

Ž . Ž .

Fig. 6. Experiment 2 Trial 5 . Mean"SEM intake of pomace–starch and pomace before and after LiCl

Ž .

administration 300 mgrkg BW to two groups of lambs. The Milo–LiCl group received milo before LiCl infusions whereas the Control group only LiCl. Intake of pomace–starch did not differ between groups

ŽP)0.05 ..

.

respectively; P)0.05; SEMs5 . When exposure increased to 8 hrday, intake of pomace was higher than intake of the pomace–starch mix on the first 2 days, but this

Ž

pattern reversed from day 3 to the end of the trial food by day interaction P-0.001; .

Fig. 4 . Average intake of the pomace–starch mix was higher than intake of grape

Ž .

pomace 252 g vs. 191 g; P-0.1; SEMs22 .

When we compared the last 20 min preference test of Period 1 with the 20 min preference test performed after Period 2, intake of the pomace–starch mix increased ŽP-0.001 , whereas intake of pomace decreased P. Ž -0.05 after Period 2, as reflected.

Ž .

in a significant test food by day interaction P-0.001; Fig. 5 .

4.2.5. Trial 5

The objective of this trial was to determine if lambs generalized an aversion from a

Ž . Ž .

familiar grain milo to a novel food pomace that contained starch. Intake of the

Ž .

pomace–starch mix decreased after LiCl administrations from 104 g to 70 g , but intake

Ž .

of pomace did not change across days 33 g to 28 g . There were significant differences

Ž . Ž .

due to day P-0.05 and food by day P-0.05 , but no differences between groups,

Ž .

group by food, group by day, or group by food by day interactions P)0.05; Fig. 6 .

5. Discussion

5.1. Energy supplement

We hypothesized that lambs first fed milo and then fed straw might acquire a preference for straw because the post-ingestive effects of milo would be experienced

Ž

while the lambs ate the straw. This temporal ordering between stimuli backward .

Že.g., short-delay conditioning; Mazur, 1994 , but it may facilitate conditioning when. flavors are subsequently associated with the post-ingestive effects of nutrients, particu-larly if the post-ingestive effects of absorbed calories occur during straw ingestion ŽBoakes and Lubart, 1988 . Nevertheless, only lambs in the experienced group in Trial 2. ŽExperiment 1 developed a weak preference for straw. That occurred only after we. Ž .

Ž .

restricted the amount of digestible energy in their basal ration Fig. 1 , which is consistent with studies showing that energy restriction enhances preferences for energy ŽCapaldi, 1990; Mehiel, 1991 . Conversely, lambs acquired a preference for straw when.

Ž .

milo was infused in the rumen before straw ingestion in Trial 3 Experiment 1; Fig. 1 . Ž

The much stronger preference for straw when lambs were infused with milo than when .

they ate milo suggests that oral experience with milo was needed for lambs to quickly discriminate between the specific flavor-post-ingestive effects of milo and straw. The strong preferences for flavored straw acquired after milo infusions indicates that the low levels of preference and intake typically displayed for this forage are mainly due to a lack of nutrient feedback from the gut and not to the forage’s appearance or to its physical structure.

Rats acquire preferences for solutions consumed shortly after glucose ingestion ŽBoakes and Lubart, 1988 . Nevertheless, the preferences are weak e.g., Capaldi et al.,. Ž

. Ž .

1987 and in some cases animals fail to display a preference e.g., Simbayi et al., 1986 because rats more strongly associate the flavor of glucose, rather than the non-nutritive

Ž .

flavor, with the calories supplied by glucose Elizalde and Sclafani, 1988 . Oral

Ž .

experience influences preference Rolls, 1986; Swithers and Hall, 1994 , and the combination of oral and post-ingestive effects are more important than either alone in

Ž .

food choices Perez et al., 1996 .

´

Lambs discriminated between milo and straw even with brief exposures on a limited

Ž .

number of occasions. Rapid post-ingestive effects may help ruminants Provenza, 1995

Ž .

and rats Melcer and Alberts, 1989 discriminate between foods eaten in close temporal association. Feedback occurs quickly when nutritious foods are ingested. For ruminants, levels of portal and jugular blood metabolites increase within minutes of beginning to

Ž .

eat Evans et al., 1975; Chase et al., 1977; deJong, 1981; Van Soest, 1994 , and responses of chemoreceptors in the gastrointestinal tract occur on the order of seconds ŽLeek, 1977; Cottrell and Iggo, 1984; Mei, 1985 . Conversely, a lack of feedback as an. animal begins to eat quickly signals that the food is poorly nutritious.

5.2. Amount ingested

Our results suggest that lambs must ingest a threshold amount of novel food for post-ingestive effects to condition a preference. On the first day of exposure to

Ž .

pomace–starch and pomace–cellulose Experiment 2; Trial 1 , lambs consumed from 18 g to 40 g of starch. Intraruminal infusions of these amounts of starch condition

Ž .

preferences for poor-quality foods in lambs Villalba and Provenza, 1997a . Conversely, lambs did not acquire preferences for flavors paired with intraruminal infusions of

Ž . Ž

cellulose Experiment 2; Trial 3 , and the maximum amount of cellulose ingested 20 g .

in Experiment 2; Trials 1 and 2 was not sufficient to condition a preference, even when

Ž .

Ž

The amount of food eaten in a meal affects aversions to novel foods Provenza et al., .

1998 . For instance, goats eating current season’s and older growth twigs from the shrub blackbrush display less preference for the novel plant part — current season’s growth or

Ž .

older growth — eaten in the greatest amount prior to toxicosis Provenza et al., 1994 . After drinking solutions of different flavors and experiencing toxicosis, rats also acquire

Ž .

aversions to the flavor consumed in the largest amount Bond and DiGuisto, 1975 .

Ž .

Results from Trial 4 Experiment 2 also suggest that lambs must eat a threshold amount of food for post-ingestive effects to influence preference. When lambs were offered a choice between novel foods — grape pomace and grape pomace–starch — for 20 minrday, they did not show a preference until day 9, when they actually began to

Ž .

prefer grape pomace, the food of lower nutritional quality Fig. 4 . The maximum amount of starch consumed on any day was only 14 g, an amount too low to condition a

Ž .

preference for pomace–starch Villalba and Provenza, 1997a . However, when the

Ž .

amount of exposure increased from 20 minrday to 8 hrday in Trial 4 Experiment 2 ,

Ž .

lambs increased preference for the pomace–starch mix Fig. 4 , and when the trial

Ž .

ended, they preferred pomace–starch over pomace alone Fig. 5 . The amounts of starch consumed during this period ranged from 59 g to 88 g, amounts that condition strong

Ž .

food preferences in lambs Villalba and Provenza, 1997a .

Collectively, these results suggest that lambs must ingest a threshold amount of food for post-ingestive effects to change preference, and that the availability of alternative foods influences if and when lambs will ingest a threshold amount of a novel food. Thus, our results suggests that preference is determined not only by nutrient

concentra-Ž .

tions in food Belovsky, 1981 , but also by the amount of the food ingested. It is likely that only plant species consumed in significant amounts foster post-ingestive effects sufficient to be relevant for herbivores to discriminate. Plant species consumed in low

Ž amounts, such as those reported in the low-rank order of diet composition tables van

.

Wieren, 1996, Watson, 1997 , probably provide nutrient input that is indistinguishable from the physiological background, and are of little importance in changing preference. This may be particularly relevant for foods of medium to low quality, where many bites may be required to reach a minimum threshold.

5.3. Generalization

Animals generalize food preferences and aversions based on past experiences. Sheep and goats prefer hays sprayed with extracts obtained from highly preferred foods Žhigh-grain concentrates; Dohi and Yamada, 1997 . Lambs made averse to cinnamon-. flavored rice — by experiencing toxicosis after eating cinnamon-flavored rice —

Ž .

generalize the aversion to cinnamon-flavored wheat Launchbaugh and Provenza, 1993 . Our results suggest that lambs discriminated among novel foods by generalizing

Ž .

flavor cues from familiar to novel foods. During Trial 1 Experiment 2 , lambs preferred

Ž .

the novel food with starch from the first day of exposure Fig. 2 , which is consistent with the notion that they generalized a preference from grains high in starch to the

Ž .

pomace–starch food. During Trial 2 Experiment 2 , lambs that ate milo and then Ž received LiCl, consumed much less of the starch–pomace mix than did Controls Fig.

.

sensory cues — probably starch — in milo and in the pomace–starch mix. Lambs showed a similar pattern of preference when we increased the proportion of starch in the mixture in the next preference test, though the differences between groups — Milo–LiCl and Control — were not significant, evidently due to variation among lambs offered a novel food combination. However, the reduction in pomace–starch intake shown by

Ž .

both groups of lambs after infusions of LiCl during Trial 2 Experiment 2; Fig. 3 , and the similar decrease in preference for pomace–starch by both groups of lambs —

Ž

Milo–LiCl and Control — after administration of LiCl during Trial 5 Experiment 2; .

Fig. 6 , argue against a very specific or robust generalization of the aversion in starch-containing foods. Collectively, these results suggest that generalization based on the starch content of familiar foods partially explains the high degree of discrimination shown by the lambs of this study.

6. Conclusions

Offering an energy supplement just prior to a poorly nutritious food did not enhance preference for the low-quality food because lambs quickly discriminated between the flavor-post-ingestive effects of the different foods. A close temporal association between the oral and post-ingestional effects of each food likely enabled lambs to discriminate between novel foods. Lambs must eat a threshold amount of a novel food in order for the post-ingestive effects to be relevant, and the availability of alternative foods determined if and when lambs ingested a threshold amount of a novel food. Generalizing over sensory cues was another mechanism involved in discriminating between novel foods.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from CSREES and the Utah Agr. Expt. Stn. This paper is published with the approval of the Director, Utah Agr. Expt. Stn., Utah State Univ. as journal paper number 7061.

References

Belovsky, G.E., 1981. Food plant selection by a generalist herbivore: the moose. Ecology 62, 1020–1030. Boakes, R.A., Lubart, T., 1988. Enhanced preference for a flavour following reversed flavour–glucose pairing.

Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 40B, 49–62.

Bond, N., DiGuisto, E., 1975. Amount of solution drunk is a factor in the establishment of taste aversion. Anim. Learn. Behav. 3, 81–84.

Burritt, E.A., Provenza, F.D., 1992. Lambs form preferences for nonnutritive flavors paired with glucose. J. Anim. Sci. 70, 1133–1136.

Ž .

Capaldi, E.D., 1990. Hunger and conditioned flavor preferences. In: Capaldi, E.D., Powley, T.L. Eds. , Taste, Experience and Feeding. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp. 157–169.

Capaldi, E.D., Campbell, D.H., Sheffer, J.D., Bradford, J.P., 1987. Conditioned flavor preferences based on delayed caloric consequences. J. Exp. Psychol: Anim. Behav. Proc. 13, 150–155.

Chase, L.E., Wangsness, P.J., Kavanaugh, J.F., Griel, L.C. Jr., Gahagan, J.H., 1977. Changes in portal blood metabolites and insulin with feeding steers twice daily. J. Dairy Sci. 60, 403–409.

Cottrell, D.F., Iggo, A., 1984. Mucosal enteroceptors with vagal afferent fibers in the proximal duodenum of

Ž .

sheep. J. Physiol. London 354, 497–522.

deJong, A., 1981. The effect of feed intake on nutrient and hormone levels in jugular and portal blood in goats.

Ž .

J. Agric. Sci. Camb. 96, 643–657.

Dohi, H., Yamada, A., 1997. Preference of sheep and goats for extracts from high-grain concentrate. J. Anim. Sci. 75, 2073–2077.

duToit, J.T., Provenza, F.D., Nastis, A.S., 1991. Conditioned food aversions: how sick must a ruminant get before it detects toxicity in foods? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 30, 35–46.

Elizalde, G., Sclafani, A., 1988. Starch-based conditioned flavor preferences in rats: influence of taste, calories and CS-US delay. Appetite 11, 179–200.

Evans, E.J., Buchanan-Smith, J.G., Macleod, G.K., 1975. Postprandial patterns of plasma glucose, insulin, and volatile fatty acids in ruminants fed low- and high-roughage diets. J. Anim. Sci. 41, 1474–1479. Henning, P., van der Linden, Y., Mattheyse, M.E., Nauhaus, W.K., Schwartz, H.M., Gilchrist, F.M.C., 1980.

Factors affecting the intake and digestion of roughage by sheep fed maize straw supplemented with maize

Ž .

grain. J. Agric. Sci. Camb. 94, 565–573.

Launchbaugh, K.L., Provenza, F.D., 1993. Can plants practice mimicry to avoid grazing by mammalian herbivores? Oikos 66, 501–504.

Leek, B.F., 1977. Abdominal and pelvic visceral receptors. Br. Med. Bull. 33, 163–168. Mazur, J.E., 1994. Learning and Behavior. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, pp. 74–75.

Ž .

Mehiel, R., 1991. Hedonic-shift conditioning with calories. In: Bolles, R.C. Ed. , The Hedonics of Taste. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 107–126.

Mei, N., 1985. Intestinal chemosensitivity. Physiol. Rev. 65, 211–234.

Ž

Melcer, T., Alberts, J.R., 1989. Recognition of food by individual, food-naive, weaning rats Rattus

.

norÕegicus . J. Comp. Psychol. 103, 243–251.

NRC, 1985. Nutrient Requirements of Sheep, 6th edn. National Academy Press, Washington, DC.

Perez, C., Ackroff, K., Sclafani, A., 1996. Carbohydrate- and protein-conditioned flavor preferences: effects of´

nutrient preloads. Physiol. Behav. 59, 467–474.

Provenza, F.D., 1995. Postingestive feedback as an elementary determinant of food preference and intake in ruminants. J. Range Manage. 48, 2–17.

Provenza, F.D., Lynch, J.J., Burritt, E.A., Scott, C.B., 1994. How goats learn to distinguish between novel foods that differ in postingestive consequences. J. Chem. Ecol. 20, 609–624.

Provenza, F.D., Villalba, J.J., Cheney, C.D., Werner, S.J., 1998. Self-organization of behavior: From simplicity to complexity without goals. Nutr. Res. Rev. 11, 199–222.

Ralphs, M.H., Provenza, F.D., Wiedmeier, W.D., Bunderson, F.B., 1995. The effects of energy source and food flavor on conditioned preferences in sheep. J. Anim. Sci. 73, 1651–1657.

Rolls, B.J., 1986. Sensory-specific satiety. Nutr. Rev. 44, 93–101.

Simbayi, L.C., Boakes, R.A., Burton, M.J., 1986. Can rats learn to associate a flavour with the delayed delivery of food? Appetite 7, 41–53.

Swithers, S.E., Hall, W.G., 1994. Does oral experience terminate ingestion? Appetite 23, 113–138. Van Soest, P.J., 1994. Nutritional Ecology of the Ruminant. Cornell Univ. Press., NY.

van Wieren, S.E., 1996. Do large herbivores select a diet that maximizes short-term energy intake? For. Ecol. Manage. 88, 149–156.

Villalba, J.J., Provenza, F.D., 1996. Preference for flavored wheat straw by lambs conditioned with intraruminal administrations of sodium propionate. J. Anim. Sci. 74, 2362–2368.

Villalba, J.J., Provenza, F.D., 1997a. Preference for wheat straw by lambs conditioned with intraruminal infusions of starch. Br. J. Nutr. 77, 287–297.

Villalba, J.J., Provenza, F.D., 1997b. Preference for flavored wheat straw by lambs conditioned with intraruminal infusions of acetate and propionate. J. Anim. Sci. 75, 2905–2914.

Villalba, J.J., Provenza, F.D., 1999. Nutrient-specific preferences by lambs conditioned with intraruminal infusions of starch, casein, and water. J. Anim. Sci. 77, 378–387.