Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 18 January 2016, At: 20:02

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

The Manpower Law of 2003 and its implementing

regulations: Genesis, key articles and potential

impact

Chris Manning & Kurnya Roesad

To cite this article: Chris Manning & Kurnya Roesad (2007) The Manpower Law of 2003 and its implementing regulations: Genesis, key articles and potential impact , Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 43:1, 59-86, DOI: 10.1080/00074910701286396

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910701286396

Published online: 08 Nov 2007.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 127

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/07/010059-28 © 2007 Indonesia Project ANU DOI: 10.1080/00074910701286396

THE MANPOWER LAW OF 2003

AND ITS IMPLEMENTING REGULATIONS:

GENESIS, KEY ARTICLES AND POTENTIAL IMPACT

Chris Manning* Kurnya Roesad*

Australian National University World Bank, Jakarta

This paper reviews Indonesia’s Manpower Law 13/2003 and related regulations, against a backdrop of slow employment growth, business concerns about the legislation and government attempts to change it in 2006. The paper focuses on severance rates and dismissals, short-term contracts and out-sourcing, and minimum wages, also briefl y discussing other articles, and comparing the law with

those in neighbouring countries. It suggests that certain articles have contributed to signifi cantly higher wage costs and reduced fl exibility in the management of labour

in Indonesia’s formal sector, even though compliance is by no means universal within the private sector. Key provisions, especially large increases in severance rates, and needs criteria imposed for the purpose of setting minimum wages, are also out of step with labour market policies in other developing countries. Circumstantial evidence suggests that these measures have adversely affected the investment climate and damaged prospects for a recovery in employment.

INTRODUCTION

In April–May 2006, a spate of major labour disputes erupted over planned revi-sions to Indonesia’s Manpower Law (13/2003) (Manning and Roesad 2006). The revisions were proposed to a law barely three years old. They emerged in a policy climate of deep concern over the rate of formal sector job creation, which had largely stalled since the fi nancial and economic crisis of 1997–98. Politically, slow

jobs growth has been bad news for a president who had set halving the unemploy-ment rate as a key objective of his administration. Unexpected strong opposition to the law from the trade union movement, which seemed to have general public support, charged that the government was set on undermining labour standards in the interests of employers and the investment climate.

The Manpower Law was long in preparation, and numerous clauses were debated heatedly both inside and outside parliament by key stakeholders in the union movement and among employer representatives. Why then was the new government of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono so intent on revising it so early? What were the articles of controversy, and what was their likely impact on labour costs?

* The authors are particularly grateful to two anonymous referees for very helpful com-ments on this paper, and to Kelly Bird, who has been engaged with both authors in re-search on labour laws in Indonesia for several years. The normal disclaimers apply.

This paper focuses on the objectives, substance and potential impact of the law and implementing legislation, including government proposals to rewrite the law in 2005–06. It is set in the context of a broader revamping of labour legislation after the downfall of Soeharto, including laws on trade unions, industrial rela-tions and social security.

Besides describing the law’s major clauses, the paper discusses its potential impact on effi ciency and equity in labour market outcomes in Indonesia. We also

raise questions about the potential impact of the law on the costs and productiv-ity of individual fi rms and industries, including the incentives or disincentives it

is likely to provide for fi rms to adjust employment and deploy labour effi ciently.

We argue that answers to the last question depend considerably on the extent to which there is compliance with the law, and hence on the costs of non-compliance. Although some empirical studies have been carried out, information on the impact of the 2003 legislation on labour outcomes (productivity, wages and employment or unemployment) is still quite limited. The analysis is therefore based mainly on the logic of microeconomic analysis, assuming that most fi rms are profi t

maximis-ers operating in relatively competitive factor and product markets.

The paper focuses on the three areas in the legislation and implementing regu-lations that have received most criticism in public debates: severance pay and dismissals; fi xed-term contract labour and out-sourcing; and minimum wages. It

also discusses several other key aspects of the law. A brief look is taken at provi-sions for implementation.

The paper is divided into fi ve major sections. In the second we present a

frame-work for thinking about the objectives and effects of labour regulations, both internationally and in Indonesia. The third section discusses in some detail key articles of the legislation, including provisions related to implementation. In the next two sections we examine plans for revision of the legislation in 2005–06, and how Indonesia’s regulations compare with standards set in several other South-east Asian countries.

FRAMEWORK OF ANALYSIS

From an economic perspective, the key goal of regulation is to correct for market failure: to guard against welfare-reducing monopolistic or monopsonistic prac-tices; to correct the distortionary impact of externalities; and to reduce frictions that impair the effi cient working of markets.1 Two other (sometimes

overlap-ping) objectives typically play a signifi cant role in labour regulation: affi rmation

of basic rights and achievement of equity goals.2 The protection of basic rights

or freedoms (such as the right to organise and bargain collectively) is fundamen-tal to most labour codes. Equity objectives are equally important, because of an assumed imbalance of power between employers and workers in negotiating

1 Although it is not directly concerned with labour markets, see Coghlan (2003) for a dis-cussion of the principles of good regulation.

2 See Engerman (2003) on the evolution of labour standards legislation and enforcement mechanisms, and Singh (2003) on the effi ciency and welfare aspects of such laws,

especial-ly in relation to labour rights on the one hand, and denial of market access or sanctions in international trade (imposed by developed countries and their consumers) on the other.

and implementing contracts, especially in relatively labour-abundant economies like Indonesia. In most labour codes, several articles (on normal hours of work, sick leave and maternity pay, and annual holidays, for example) seek to protect workers and constrain the actions of employers. They also seek to provide social safety nets for vulnerable workers (children, for example), or to prevent remu-neration from falling below levels required to meet nationally recognised ‘basic needs’.

The popular perception that labour legislation is mainly about issues of equity means that reform aimed at providing greater fl exibility can be a complex

politi-cal challenge (Freeman 1993). The sentiments of the general public are often easily infl uenced by organised labour campaigns that draw attention to the ‘David and

Goliath’ dimensions of the struggle to gain a better deal from employers; thus the public frequently regards any reform in the direction of fl exibility as inequitable

from the narrow perspective of the balance of benefi ts accruing to workers

com-pared with employers (Felipe and Hasan 2006: 72; Lindsey and Masduki 2002). Much less weight is given to the potential, but less tangible, benefi ts from reform

for those without a job or with a less preferred job, especially workers in low productivity agriculture or the informal sector, who might benefi t from access to

formal sector jobs in a more fl exible labour market.

In practice, interest groups typically play an important role in the creation (or revision) of legislation. In the case of labour, not only do groups of employers and workers stand to be affected by the content of labour regulations, but govern-ments may also enhance their populist credentials through labour policies (wage and labour protection policies for the formal sector, for example). Typically, leg-islation is heavily infl uenced by the interests of well-organised minority groups,

employer organisations and trade unions. The majority of workers (especially informal sector workers) are not represented by trade unions, but their incomes and job prospects are affected by legislation. They, and consumers who bear the cost of increased prices, play only a minor role in shaping the law, as is the case with dispersed and poorly organised groups more generally in economic deci-sion making (Olson 1965). Bureaucrats can expect to gain by extracting rents from participants, especially from employers, as they exercise discretionary power in enforcing the laws.3

It can be argued that the pursuit of equity goals in labour legislation is inher-ently more diffi cult in low-income countries like Indonesia than in more developed

countries. Two considerations are especially important. First, a high proportion of workers are engaged in low-income informal sector employment outside the pur-view of labour legislation. Besides protecting a relatively small proportion of the workforce, the legislation potentially drives a wedge between the small formal and the larger informal sector in terms of earnings and working conditions.

While many observers agree that less equal income distribution between the two sectors in poor countries is a small price to pay for more humane conditions of work in the formal sector (Elliot and Freeman 2003: 19),they should be less

3 Botero et al. (2003) suggest that from an institutional perspective one can assess laws using a political power approach, which takes the desire of power-holders to benefi t

them-selves at the expense of opposition groups as one important motive for introducing or changing legislation.

comfortable with the possibility that legislation is welfare reducing for a signifi cant

proportion of the population. Legislation can reduce or, probably more impor-tantly, slow the growth of employment opportunities in the formal sector if it contributes to higher than market-clearing wages in competitive product mar-kets. Workers are forced to seek lower paying jobs in the informal sector or suffer unemployment. To borrow terminology used in slightly different contexts, ‘insid-ers’ gain relatively, and also at the expense of ‘outsid‘insid-ers’ (Lindbeck and Snower 2001).4 Proponents of greater regulation, on the other hand, argue that higher

wages and more stable employment arrangements can promote increased pro-ductivity, assuming that employers have an imperfect understanding of this rela-tionship (e.g. Akerlof 1982), and are unlikely to raise wages for this purpose of their own accord.

Second, rates of compliance with legislation matter, and are likely to be more problematic in developing than in developed countries. If rates of compliance with legislation are low, because of low rates of unionisation or poor enforcement mechanisms, then both positive welfare effects in the modern sector and negative welfare effects in the informal sector are much reduced, and may be irrelevant. Some commentators have demonstrated that it is hard to fi nd a link between

more stringent labour standards legislation and labour market outcomes, argu-ing that legislation is often a ‘paper tiger’, especially when labour market condi-tions deteriorate because of unexpected economic shocks (Freeman 1993).

One dimension of the regulatory environment and of compliance (for labour law and more generally) is that both tend to be more stringent in larger and foreign establishments than in smaller-scale and domestic fi rms. In the case of

labour laws, this occurs for a number of reasons. Sometimes the distinction is embedded in law, as in India’s Industrial Disputes Act, which distinguishes between fi rms with 100 employees or more and those that employ fewer

work-ers in setting procedures for dismissals (Asher and Mukhopadhaya 2006). Com-pliance can also differ, given that larger and foreign fi rms are more visible, more

likely to be unionised, and more accessible to labour inspectors. On the other hand, larger fi rms are likely to offer bigger bribes, and at the same time they may

be in a stronger position than small fi rms to resist unwanted incursions from

labour inspectors.

Implications for Indonesia

What are the implications for Indonesia? First, it does have a thriving informal sector, which (together with agriculture) appears to have played a major role in absorbing labour in the post-crisis period. Well over half of all persons employed in non-agricultural activities are classifi ed as self-employed, family workers or

casual wage employees (Alisjahbana and Manning 2006).5 In addition, small and

cottage establishments account for a high proportion of all employment.

Two points are worth making with regard to the compliance regime. First, one would expect compliance to be relatively low, given the structure of wage

4 The insider–outsider distinction in the literature on developed countries often refers to unionised versus non-unionised workplaces.

5 A small proportion of the self-employed (around 10%) tend to be better educated and involved in more highly skilled activities.

employment by fi rm size. More than half of all manufacturing employees worked

in establishments with less than 20 workers (formally classifi ed as ‘small’) in 2004,

and the majority of these were in cottage industries with less than fi ve

employ-ees. Similar distributions can be expected to exist in service industries. Second, although still low, compliance with regulations has probably increased among larger fi rms in recent times. Trade union freedoms are now formally guaranteed,

and union membership has risen steeply.6 There are now greater pressures for

fi rms to comply with legislation, especially given a Ministry of Manpower that is

more sympathetic to trade union interests.

What about the payment of bribes to circumvent legislation? While changed political circumstances and recognition of trade union rights may give organ-ised labour greater infl uence and protection at the enterprise level, this may be

counter-balanced to some extent by the ‘decentralisation of corruption’ in gov-ernment enforcement processes, the latter perhaps having greater infl uence on

medium-scale and smaller fi rms than on large fi rms in the regions.

In sum, we would expect the labour regulations still to be relatively limited in their impact, since they cover only 20% or less of all employed persons. How-ever, on balance, we could expect new labour regulations and a tighter compli-ance regime to have signifi cant backwash effects on formal sector employment

growth—certainly greater than during the Soeharto era, when enforcement mech-anisms were much weaker.

Recent initiatives to revise Indonesia’s labour laws have arisen out of concern about employment growth in the formal sector. Successive governments have faced a major employment challenge since the fi nancial crisis and the fall of

Soe-harto in 1998. There are three key dimensions to this challenge. First, economic growth rates have been low, both compared with high-performing economies such as China, India and Vietnam, and compared with the pre-crisis years (below 5% on average during 2000–05, compared with over 7% for much of the pre- crisis period). Second, regular wage employment in the formal sector has grown very slowly if at all, having recovered immediately after the crisis (Manning and Roe-sad 2006). The latter has applied equally to non-tradable industries and to key tradable industries such as manufacturing.7 Third, unemployment rates have

remained stubbornly high, and indeed probably increased slightly in 2005–06 to just over 10%. While we do not presume that labour regulations by themselves have contributed in any signifi cant degree to slower rates of economic growth,

we feel it is much more likely that slow growth in regular wage employment and persistently high unemployment can be attributed to overly restrictive labour regulations. That is, employers may have adopted strategies to conserve on the use of labour for a given level of output, and also have been reluctant to take on new hires.

6 Some estimates put membership at around 10 million, or 30–40% of all wage employ-ment, although it is doubtful that a high proportion of members pay union dues or partici-pate actively in negotiations with employers.

7 Precise comparison of pre- and post-crisis employment performance is complicated by changes in defi nitions of unemployment and ‘regular’ wage employment in 2001.

MANPOWER LAW 13/2003

Indonesia’s employment legislation is at the core of a newly emerging democratic collective bargaining process. Five major pieces of labour-related legislation have been enacted since the fall of the Soeharto regime: the Trade Union Law (21/2001); the Manpower Law (13/2003); the Industrial Disputes Settlement Law (4/2004); the Migrant Worker Law (39/2004); and the Social Security Law (40/2004). In addition to breaking new ground, these laws bring together articles already con-tained in government and ministerial regulations passed over 40 years.8 They are

necessary steps towards providing an accessible, transparent and consistent set of regulations for labour, management and government, and a comprehensive set of codes on social protection for Indonesia’s workers.

Our focus in this paper is on the provisions of the Manpower Law of 2003, although there are important links between this law and the laws on trade unions and industrial relations (both of which have major implications for the actual setting of labour conditions in the workplace through collective bargaining and dispute settlement). Both business and economic policy makers have expressed concern that certain aspects of this legislation—especially of the Manpower Law—are too rigid. They argue that the reforms have both raised costs and lim-ited employers’ fl exibility to set wages and hire and fi re workers in response to

individual fi rm circumstances and to labour market conditions across industries

and regions.

Revisions to labour laws have a long history. A new Manpower Law (25) was issued in 1997, but was annulled after the fall of Soeharto in 1998, on the grounds that a tainted political process had produced it. Prior to this, the basic principles governing work in Indonesia were set in Law 1/1951 and Law 14/1969, aug-mented by several basic laws and government regulations, a plethora of minis-terial regulations, decrees and instructions or edicts, and a handful of circulars issued by the relevant directors general in the ministry.9 Whereas Law 1/1951

provided details of basic protection for workers (such as normal working hours, maximum hours of work, restrictions on the employment of child and female workers, and annual leave), Law 14/1969 was a short document stating broad principles guiding employment, health and safety norms and labour protection.

Manpower Law 13/2003 is a vastly different document, containing some 18 chapters, 193 articles and close to 500 clauses. Besides labour protection, the law deals with several very general topics such as equal opportunity, manpower planning and placement, training, and the government’s obligation to provide employment, as well as basic guidelines for industrial relations (including collec-tive labour agreements, but not including details for the establishment of labour courts). The key clauses on labour protection and contracts that are the focus of this paper are contained in three chapters entitled Employment Relations; Protec-tion, Wages and Welfare; and Termination of Employment (chapters 9, 10 and 12, respectively), covering some 75 of the law’s articles.

8 See Ministry of Manpower (no date; probably 1991) and Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration and ILO (2005a, 2005b) for collections of earlier and more recent regula-tions and laws.

9 Expressed respectively in Indonesian as peraturan, keputusan, instruksi and surat edaran from the Minister of Manpower.

The main areas of controversy

The main clauses of Manpower Law 13/2003 that are generally viewed as adversely affecting employment relate to the hiring and fi ring of workers (in

par-ticular, to severance pay); to sub-contracting and fi xed-term contracts (FTCs); and

to the setting of minimum wages. Provisions on severance pay and on sub-con-tracting and FTCs received most criticism from employer groups after the law was enacted, and several were central to proposals for reform of the labour laws in 2005 and 2006.

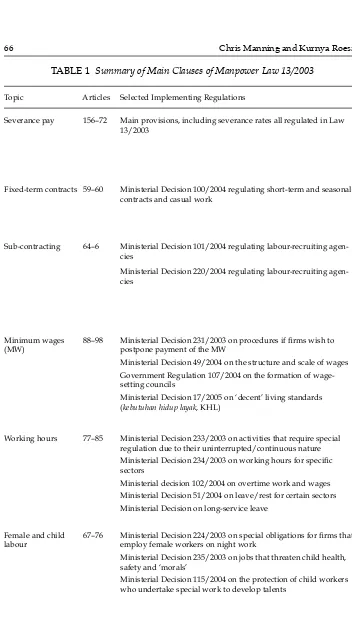

Table 1 summarises several of the main provisions in these areas of the law. Some of the key implementing legislation is also documented in the table, since the law has necessitated a raft of implementing regulations, most of which have been introduced by the Ministry of Manpower.10

Severance pay

Severance pay is a major form of compensation for employees who lose their jobs, especially in developing countries that have no alternative form of unemployment benefi ts (Vodopivec 2004).11 Typically it is paid as a lump sum when employees

are dismissed or leave a job for reasons beyond their control (such as in cases of bankruptcy or as a result of policies adopted by new owners of a fi rm). Severance

is most commonly paid by employers, although in some countries employees also contribute to more fl exible unemployment insurance accounts which they can

access on separation, including if they quit voluntarily. Since severance payments are normally positively related to years of service, they tend to promote longer employment. Severance thus can act as a disincentive for older workers to seek new jobs, and for fi rms to dismiss workers (especially older workers) or to take

on new recruits, thus limiting job opportunities for the unemployed. On the other hand, benefi ts may accrue in terms of improved productivity. It is also argued

that longer-term employment relationships encourage employers to put more emphasis on training and, potentially, foster greater loyalty between employers and employees (Vodopivec 2004: 97–9).

Severance pay has long been the primary source of unemployment benefi ts

for most wage workers in larger fi rms in Indonesia.12 Its impact on effi ciency

and equity could be considered to have been relatively benign in the past, partly because rates of severance pay were relatively low, and partly because compliance with labour legislation was reported to be low (see, for example, Suryahadi et al. 2003). This has changed in recent years, as Indonesia now has one of the most expensive severance pay regimes among all developing countries (LP3E–Unpad 2004: fi gure 4.2; table 6.1).

10 Some issues have been regulated by presidential decree or general government regu-lation.

11 Severance pay regulations frequently go hand in hand with laws dealing with long-service payments. We do not make a distinction between the two in this discussion. 12 It was regulated by Ministry of Labour (Manpower) Regulation 9/1964 in conjunction with Law 12/1964 on Dismissals, and then later revised several times, in 1986 (Ministerial Regulation 4), 1996 (Ministerial Decree 3) and 2000 (Ministerial Decree 150), before being incorporated into the Manpower Law of 2003.

TABLE 1 Summary of Main Clauses of Manpower Law 13/2003

Topic Articles Selected Implementing Regulations

Severance pay 156–72 Main provisions, including severance rates all regulated in Law 13/2003

Fixed-term contracts 59–60 Ministerial Decision 100/2004 regulating short-term and seasonal contracts and casual work

Sub-contracting 64–6 Ministerial Decision 101/2004 regulating labour-recruiting agen-cies

Ministerial Decision 220/2004 regulating labour-recruiting agen-cies

Minimum wages (MW)

88–98 Ministerial Decision 231/2003 on procedures if fi rms wish to

postpone payment of the MW

Ministerial Decision 49/2004 on the structure and scale of wages Government Regulation 107/2004 on the formation of wage-setting councils

Ministerial Decision 17/2005 on ‘decent’ living standards (kebutuhan hidup layak, KHL)

Working hours 77–85 Ministerial Decision 233/2003 on activities that require special regulation due to their uninterrupted/continuous nature Ministerial Decision 234/2003 on working hours for specifi c

sectors

Ministerial decision 102/2004 on overtime work and wages Ministerial Decision 51/2004 on leave/rest for certain sectors Ministerial Decision on long-service leave

Female and child labour

67–76 Ministerial Decision 224/2003 on special obligations for fi rms that

employ female workers on night work

Ministerial Decision 235/2003 on jobs that threaten child health, safety and ‘morals’

Ministerial Decision 115/2004 on the protection of child workers who undertake special work to develop talents

Source: Manpower Law 13/2003 and implementing regulations.

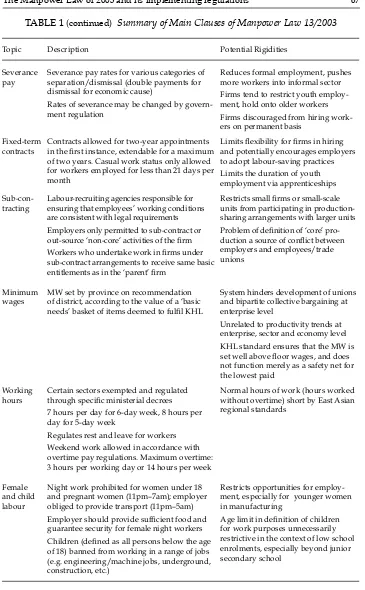

TABLE 1 (continued) Summary of Main Clauses of Manpower Law 13/2003

Topic Description Potential Rigidities

Severance pay

Severance pay rates for various categories of separation/dismissal (double payments for dismissal for economic cause)

Rates of severance may be changed by govern-ment regulation

Reduces formal employment, pushes more workers into informal sector Firms tend to restrict youth employ-ment, hold onto older workers Firms discouraged from hiring work-ers on permanent basis

Fixed-term contracts

Contracts allowed for two-year appointments in the fi rst instance, extendable for a maximum

of two years. Casual work status only allowed for workers employed for less than 21 days per month

Limits fl exibility for fi rms in hiring

and potentially encourages employers to adopt labour-saving practices Limits the duration of youth employment via apprenticeships

Sub-con-tracting

Labour-recruiting agencies responsible for ensuring that employees’ working conditions are consistent with legal requirements Employers only permitted to sub-contract or out-source ‘non-core’ activities of the fi rm

Workers who undertake work in fi rms under

sub-contract arrangements to receive same basic entitle ments as in the ‘parent’ fi rm

Restricts small fi rms or small-scale

units from participating in

production-MW set by province on recommendation of district, according to the value of a ‘basic needs’ basket of items deemed to fulfi l KHL

System hinders development of unions and bipartite collective bargaining at enterprise level

Unrelated to productivity trends at enterprise, sector and economy level KHL standard ensures that the MW is set well above fl oor wages, and does

not function merely as a safety net for the lowest paid

Working hours

Certain sectors exempted and regulated through specifi c ministerial decrees

7 hours per day for 6-day week, 8 hours per day for 5-day week

Regulates rest and leave for workers Weekend work allowed in accordance with overtime pay regulations. Maximum overtime: 3 hours per working day or 14 hours per week

Normal hours of work (hours worked without overtime) short by East Asian regional standards

Female and child labour

Night work prohibited for women under 18 and pregnant women (11pm–7am); employer obliged to provide transport (11pm–5am) Employer should provide suffi cient food and

guarantee security for female night workers Children (defi ned as all persons below the age

of 18) banned from working in a range of jobs (e.g. engineering/machine jobs, underground, construction, etc.)

Restricts opportunities for employ-ment, especially for younger women in manufacturing

Age limit in defi nition of children

for work purposes unnecessarily restrictive in the context of low school enrolments, especially beyond junior secondary school

Increases in severance pay rates had already occurred under the Soeharto regime, and have been a controversial issue for some years.13 Ministerial Decree

3/1996 increased rates of severance and long-service pay by approximately 50%, for dismissals due both to economic cause and to minor offences.14 This raised

rates of total severance pay to levels that were moderately high by international standards.15 In 2000, Ministerial Decision 150/2000 increased severance rates

fur-ther, mainly for workers with 10 or more years of service, and granted long-service pay to all workers who voluntarily quit their jobs. Controversially, long-service payments were also extended to workers who committed major offences.

Manpower Law 13/2003 affi rmed most of these rights, and raised severance pay

rates further for workers with three or more years of service (article 156). Workers were also entitled to a gratuity amounting to 15% of all severance and long-service payments in compensation for loss of housing and health care coverage provided by the fi rm,16 even for workers dismissed for committing minor offences. But

under pressure from employer groups, the law abolished the legal right granted in 2000 to long-service payouts for all workers who quit or who were dismissed for major offences. Instead it mandated a separation payment in these cases, to be determined in company regulations or collective labour agreements.

The law stipulates that a worker should receive severance and long-service pay for separation or dismissal due to a range of additional causes. These include dis-missal following a takeover of the fi rm (article 163); loss of job as a result of a

pub-licly audited bankruptcy and fi rm closure after two years of losses (article 164);

and retirement or chronic illness, disability or death of an employee (article 167). In the case of dismissal after takeovers, or separation from the fi rm on retirement,

or due to illness or death of the employee, severance and long-service payments are set at the same rate as dismissal for economic cause (i.e. twice the basic rate).17

Employees receive only the basic rates of severance and long- service leave pay in cases of dismissal due to publicly audited bankruptcy, or where employees opt to leave a newly constituted fi rm in the case of a takeover.

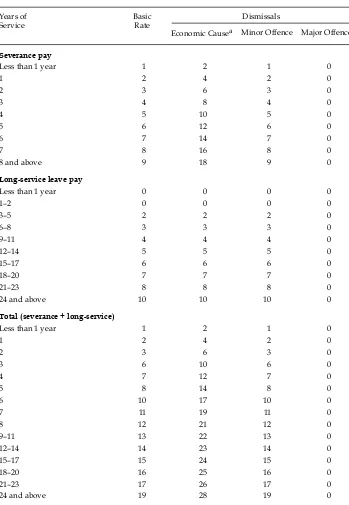

Table 2 summarises these rates due to dismissal for (i) economic reasons (referred to in the law as ‘actions to improve effi ciency’); (ii) minor offences; and

(iii) major violations or offences.18 For the most common category of worker

13 This part of the paper closely follows LP3E–Unpad (2004).

14 Economic cause refers to rationalisation measures, such as downsizing or restructuring, for the purpose of improving effi ciency. Minor offences are defi ned as actions that contravene

labour contracts, company regulations, or clauses in collective labour agreements. Workers may be dismissed for such offences after receiving a written warning on three occasions. 15 Workers with 10 and 20 years experience were eligible for 12 and 15 years of pay, re-spectively, for dismissal for economic cause.

16 Firms were also required to compensate dismissed workers for accrued annual leave entitlements and for the cost of repatriation to the place where they were recruited. 17 If employers contribute to retirement schemes for their employees, they are liable for severance payments only if the lump sum retirement payments are less than the mandated value of the severance and long-service payments.

18 According to the law, major violations include theft of company property or materials; violent behaviour in the workplace; causing damage to equipment; drunkenness in the workplace; and similar behaviour (article 158).

TABLE 2 Severance Pay Rates according to Manpower Law 13/2003 (in months of salary)

Years of Service

Basic Rate

Dismissals

Economic Causea Minor Offence Major Offence

Severance pay

Less than 1 year 1 2 1 0

1 2 4 2 0

2 3 6 3 0

3 4 8 4 0

4 5 10 5 0

5 6 12 6 0

6 7 14 7 0

7 8 16 8 0

8 and above 9 18 9 0

Long-service leave pay

Less than 1 year 0 0 0 0

1–2 0 0 0 0

3–5 2 2 2 0

6–8 3 3 3 0

9–11 4 4 4 0

12–14 5 5 5 0

15–17 6 6 6 0

18–20 7 7 7 0

21–23 8 8 8 0

24 and above 10 10 10 0

Total (severance + long-service)

Less than 1 year 1 2 1 0

1 2 4 2 0

2 3 6 3 0

3 6 10 6 0

4 7 12 7 0

5 8 14 8 0

6 10 17 10 0

7 11 19 11 0

8 12 21 12 0

9–11 13 22 13 0

12–14 14 23 14 0

15–17 15 24 15 0

18–20 16 25 16 0

21–23 17 26 17 0

24 and above 19 28 19 0

a The law defi nes dismissals due to economic cause as rationalisation measures undertaken by the fi rm. In such cases the worker is entitled to two times the basic rate of severance pay plus one time

the long-service pay.

Source: Manpower Law 13/2003, art. 156, contains basic rates of severance and long-service payments.

separation—layoffs or dismissals for economic cause—two points are worth stressing. First, as noted by several commentators, severance payments rose in Indonesia at a time when they were falling in many other countries in the world (LP3E–Unpad 2004; Bird 2005). Second, severance pay has increased not only because of changes in the rates of severance and long-service payments, but also because minimum wages, on which severance or long-service pay is based, have increased quite signifi cantly in real terms in recent years. This occurred especially

over the period 2000–03, when there was an ill-timed coincidence of very large increases in both severance pay rates and real minimum wages (Manning 2006; see below for details). Further, especially rapid increases in severance rates applied to workers with 10 years of service or more (by 70–80% from 2000 to 2003).

The potential impact of the 2003 law on the cost of fi ring workers was quite

dra-matic. To illustrate, we take the case of workers with 10 years of service dismissed for economic cause in 2003 compared with three years earlier, assuming that mini-mum wage increases were passed on to these workers in full. The combination of an increase in real minimum wages of just under 50% on average (unweighted) across all provinces, together with an increase in severance pay rates of just over 80%, would have resulted in an astonishing 170% increase in real (constant price) sever-ance costs for employers (table 3).19 The increases in total severance costs would

have been even greater in major industrial regions—Jakarta, Bandung and Sura-baya—where minimum wages rose more rapidly than the (unweighted) national average. It is no surprise, therefore, that the fl ight of capital out of labour-intensive

industries—especially footwear, garments and toys—to Vietnam and China was reported as particularly marked in this period (Alisjahbana and Manning 2002).

As noted above, increases in mandated severance rates (and long-service pay-ments) in this period differed for groups of workers according to years of service: they were signifi cantly higher for employees with 10 years of service or more

(table 4), thus making it relatively more costly for employers to dismiss experi-enced workers.

Minimum wages have increased more slowly since 2002 in most provinces (see below) and severance rates have not changed since 2003. The period 2000–03 must be regarded as an unusual episode in the post-Soeharto era, when the govern-ment sought to accommodate demands and curry political favour with a newly enfranchised labour movement that had suffered abuse of its rights under the New Order.20 Nevertheless, severance costs rose to a new plateau in this period,

which probably helps account for the slow growth of modern sector employ-ment since the crisis. Importantly, however, article 156 (5) of the Manpower Law

19 Data for West Java and East Java are proxied by severance rates for the major pro-vincial capitals of Bandung and Surabaya, respectively. The assumption that increases in minimum wages are passed on to experienced workers is probably realistic with respect to more labour-intensive fi rms with fl atter earnings distributions for a high proportion of

mainly unskilled and semi-skilled workers. But it is probably less realistic in the case of more skill- and capital-intensive fi rms.

20 Some of these excesses are documented in Hadiz (1997). Successive ministers of man-power were former trade union leaders and members of major political parties under the Habibie and Megawati governments, and there was a general presumption that pro-labour policies could deliver signifi cant votes among the urban working class.

TABLE 4 Rise in Real Severance Costs and Contribution of Increases in Severance Rates and Minimum Wage Rates, by Years of Service, 2000–03a

(%)

Years of Service

% of Increase in Severance Costs Due to Rise in Increase in Real

a For employees dismissed for economic cause.

b Unweighted mean for all Indonesian provinces, using Bandung and Surabaya as proxy for West and East Java, respectively.

c Nominal rates/costs defl ated by the CPI.

Source: As for table 3.

TABLE 3 Rise in Real Severance Costs and Contribution of Increases in Severance Rates and Minimum Wage Rates, by Firm Location, 2000–03a

(%)

Increase in Real Minimum

Wageb

% of Increase in Severance Costs Due to Rise in

Indonesia averageb 47.5 49 51 100 170

Jakarta 65.2 41 59 100 203

Bandung 90.8 33 67 100 250

Surabaya 83.6 35 65 100 237

a For employees with 10 years of service dismissed for economic cause. Nominal rates defl ated by

the CPI.

b Unweighted mean for all provinces, using Bandung and Surabaya as proxy for West and East Java, respectively.

c Regulated severance pay rates (including long-service pay) increased from 12 months pay in 2000 (prior to the enactment of Ministerial Decree 150) to 22 months after the passing of Law 13 in 2003. d Nominal rates/costs defl ated by the CPI.

Source: Ministry of Manpower, unpublished data on minimum wage rates; Ministerial Decrees 3/1996 and 150/2000 and Law 13/2003.

provides some leeway for revisions to levels of severance and long-service pay, as well as to the 15% gratuity, by government regulation rather than through the politically more diffi cult route of amendments to the law itself.21

Fixed-term contracts and sub-contracting

There is quite a wide range of international practice with regard to restrictions on FTCs for wage employees (IFC 2006). The issue has been especially important in debates on labour regulations in Latin America, where it has been argued that tight controls over FTCs have severely limited fl exibility of production and the capacity

of fi rms to respond to fl uctuations in product demand (Cox-Edwards 1997: 137).

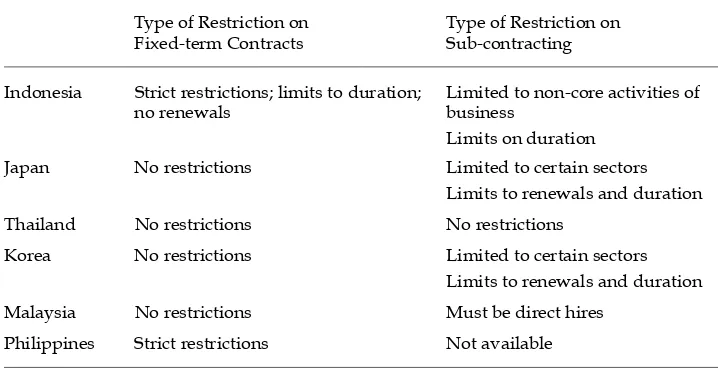

In some countries in Asia (such as the Philippines and India), tight controls are imposed on either the duration of FTCs or the conditions under which they are permitted, while in others (e.g. Malaysia and Thailand) no restrictions are imposed (Felipe and Hasan 2006; Felipe and Lanzona 2006).

In the broader context of a dualistic labour market, FTCs in the modern sector link the formal and informal labour markets. Such contracts can thus offer work-ers a stepping-stone into more permanent employment relationships in the mod-ern sector, while at the same time giving fi rms greater opportunities for fl exibility

in production and exporting. Sub-contracting or putting-out can achieve similar objectives. In addition to the need for fl exibility to meet fl uctuating purchase orders,

wide variation in the seasonal production of agriculture-based commodities makes sub-contracting an important strategy for some producers in countries like Indo-nesia. However, questionable arguments are made on equity grounds—from a view that indefi nite-term or permanent contracts should be the norm—for regulating the

duration of contracts, the frequency of fi xed-term contract re-negotiation, and the

use of sub-contracting. Employers, it is reasoned, should not be allowed repeat-edly to re-appoint contract workers, or to sub-contract major operations, in order to avoid incurring the fi xed costs of a more permanent employment relationship.

The new labour law places tighter restrictions on FTCs, while temporary work contracts are permissible only for the duration of a three-month probation period. Under articles 59 and 60 of the Manpower Law and the related Ministerial Decree 100/2004, FTCs are limited to three years (two years plus a one-year extension), compared with three years extendable once (hence a maximum period of six years) in the previous legislation. Further, the new legislation permits sub-contracting only for certain activities:

• temporary or one-off activities;

• seasonal contract work or daily work not exceeding three months; • work that is expected to be completed within three years;

• jobs related to the introduction of new products on trial.

As with severance pay regulations, these measures go against the trend in international practice. While there are limitations on repetitive contract renewal in some OECD countries, for example, these are now relatively liberal, and the

21 However, revisions to articles that stipulate that the employer must pay twice the rate of severance for certain cases of separation or dismissal (such as those for economic cause or after a takeover, or upon retirement) can be changed only through revisions to Man-power Law 13/2003.

minimum duration of contracts is generally three years or more.22 It can be

argued that restrictions are harmful to fl exibility at a time when international

practice is moving towards shorter rather than longer employment contracts in many industries.

Articles 64–66 of the Manpower Law regulate sub-contracting (often also referred to as out-sourcing). The regulations limit sub-contracting to ‘non-core’ activities of a fi rm.23 Three aspects of sub-contracting need to be distinguished.

First, a fi rm can out-source (or sub-contract) certain components of production.

An example would be the case of garment producers sub-contracting the produc-tion of buttons to small-scale and cottage industries. Second, a fi rm may hire

cer-tain services from specialised enterprises, such as catering or cleaning or security, although there is some uncertainty as to what services precisely are permitted. In both cases, protection of workers and working conditions is the responsibility of the supplier fi rm, and must be at least of the same standard as in the ‘core’ fi rm.

Third, sub-contracting also covers labour out-sourcing or the activities of labour suppliers. Article 66 of Manpower Law 13/2003 states that labour placement agencies can be hired only to provide workers carrying out non-core services or activities. The core fi rm is ultimately responsible if the supplier fi rm cannot fulfi l

its obligations.

These employment arrangements are likely to limit formal sector job growth, as employers are denied the opportunity to hire new labour in response to sharp, short-term changes in product demand. A survey of employment practices con-ducted at Padjadjaran University in Bandung in the years immediately before the enactment of the Manpower Law found that fi rms reportedly increased their

use of fi xed-term contract employment from 2001 by around 8%, especially in

manufacturing, as part of restructuring efforts (LP3E–Unpad 2004: fi gure 5.5).

According to this study (p. vii):

Firms feel that in the current volatile and uncertain business environment, the ex-cessively costly severance regulations have contributed to pressure … to rationalise their workforces and [have] discouraged some fi rms from hiring new workers on a

permanent basis.

It seems likely that the new restrictions imposed on employment under fi xed

contracts will make these strategies more diffi cult. In short, fi rms are now

trapped between the high costs of dismissing regular workers (refl ected in high

severance costs) and tight restrictions on employment of workers on fi xed-term

contracts.

22 In the OECD, only one of 28 countries limits contract renewal to one occasion only, and only fi ve countries limit the duration of contracts to three years or less, while the majority

place no restrictions on the duration of fi xed contracts (OECD 2004).

23 The distinction between ‘core’ and ‘non-core’ activities is not clearly defi ned in the law,

which refers only to activities that are ‘not directly related to main activities or those relat-ed to the production process, except supporting service activities …’ (article 66, clause 1). Services such as catering, transport and recruiting activities are generally regarded as non-core.

Minimum wages

Minimum wage policy is probably the most important and controversial area of research dealing with the impact of labour standards on effi ciency,

employ-ment and equity. As in developed economies, the received wisdom has been that minimum wages are harmful to employment. Economic policy refl ects this view

in several successfully industrialising East Asian countries, such as Korea, Tai-wan, Malaysia and Singapore, where minimum wages either were never intro-duced at all, or were brought in only after the country industrialised. According to the conventional view, minimum wages tend to have large negative effects on employment in the formal sector (where they are more likely to be binding). Dis-placed formal sector workers who have no access to unemployment insurance spill into the informal sector and depress wages in activities where most of the poor are found.

Some research fi ndings, albeit controversial ones, have questioned the negative

impact of minimum wages on labour demand in industrial economies, leading to a renewed interest in the subject in both developed and developing countries.24

However, the research also indicates that negative longer-term effects on employ-ment may be considerably greater than those in the short term, as fi rms adjust

technology to more permanent perceptions of higher real wages.25 Empirical

research in developing countries (mainly in Latin America) suggests that mini-mum wages have had little impact on employment, either because the minimini-mum wage was set well below the average market wage, or because of low levels of compliance (Cox-Edwards 1997). Some researchers have drawn attention to a number of countervailing forces having a positive impact on jobs in the informal sector: minimum wages can boost demand for informal sector goods and employ-ment, can have a ‘lighthouse’ effect on the wage distribution in the unprotected informal sector (acting as a benchmark for ‘fair remuneration’), and may lead to a re-allocation of capital into more labour-intensive, uncovered sectors (Lustig and McLeod 1996; Saget 2001).

There have been similar debates in the case of Indonesia, although few stud-ies have focused on formal–informal sector relationships. Islam and Nazara (2000) and Alatas and Cameron (2003) found little evidence of signifi cant

back-wash effects on modern sector employment from minimum wage increases that occurred during the Soeharto era. Similarly, Rama (1996) found that while mini-mum wages had a negative impact on employment in small-scale fi rms, this was

not the case in larger fi rms in the pre-crisis period. According to other studies,

however, several of which use more recent data, minimum wages have adversely affected employment. Suryahadi et al. (2003) fi nd this, especially among youth,

less educated people and females, during both the pre- and post-crisis periods; Harrison and Scorse (2004) found that minimum wages reduced employment in

24 The most infl uential study was that of Card and Krueger (1994). Other studies in the

USA have shown statistically signifi cant negative effects of minimum wage increases on

youth employment in the labour market (see, for example, Neumark and Wascher 1992; and Burkhauser and Harrison 2000).

25 See Baker, Benjamin and Stranger (1999). In Card and Krueger, the best known of the studies challenging the received wisdom, the authors looked at changes over 1–2 years only.

textiles, although not in garments. Finally, Bird and Manning’s (2002) research, which focused on formal–informal sector inter-relationships, led to the conclusion that minimum wage interventions expanded the informal sector and depressed the earnings of some groups of workers in this sector in the post-crisis period.26

What was the institutional context underpinning these studies? In the pre-cri-sis period, minimum wages had emerged as a key policy instrument aimed at raising the incomes of formal sector workers (Manning 1998). They were set for each province by the minister of manpower on the recommendation of the gov-ernor, who in turn was advised by wage councils. Minimum living needs ( kebu-tuhan hidup minimum, KHM) had become the main basis for relating minimum wages to the needs of workers at the provincial level before the crisis in 1997–98. In the late 1990s, the ministry had introduced a higher benchmark for assessing the adequacy of minimum wages: kebutuhan hidup layak (KHL), requirements for a ‘decent’ standard of living. The introduction of KHL was delayed because of the crisis, and it was formally affi rmed as the main standard for setting minimum

wages in the Manpower Act of 2003.

An important change in the policy framework took place with decentralisation in 2001.27 Responsibility for setting minimum wages was moved away from the

central government and turned over to the provincial and district/municipality (kabupaten/kota) governments. Before the enactment of Manpower Law 13/2003, minimum wages were regulated through ministerial decrees. However, general principles for setting minimum wages established in earlier legislation were incorporated into the new law (articles 88–98). The law, together with implement-ing legislation, mandated the followimplement-ing mechanisms and principles for settimplement-ing minimum wages:28

• Minimum wages are set at provincial and district/municipality level. They can be sector-based, and apply to all workers at the bottom of the wage scale, including those who are employed for less than one year. They are to be ratifi ed

by the governor based on recommendations from the district head (bupati) or mayor (walikota). Provincial minimum wages set the fl oor to wages for all

districts in a given province (that is, district/municipal minimum wages may be higher but not lower than province minima).

• Minimum wage levels are based on the value of a ‘decent’ standard of living (KHL), as discussed above. Implementing legislation provides details of the components (49 in all) of the KHL standard. The law also includes guidelines for collection of data on prices of these components from traditional markets by tripartite wage councils at the provincial and district level. Members of the councils include representatives of the local government statistics offi ce.

• In contrast with many other countries which review minimum wages every two to three years, minimum wages in Indonesia are reviewed annually.

26 The effects on employment were strongest after the 1997–98 economic crisis, when real minimum wages were increased substantially in an environment of low economic growth.

27 Minister of Manpower Decision 226/2000.

28 The main implementing regulation relates to the process for determining the KHL (Ministerial Regulation 17/2005).

There are several contentious issues in the provisions of the law (Widianto 2004). First, the current system allows districts to recommend their own mini-mum wages to provincial authorities (with the lowest recommended district wage likely to become de facto the province minimum). While this has the poten-tial to improve fl exibility, it also allows for the possible continuation of the

confl icting signals that have frequently accompanied new regional regulations

since reformasi. Second, while minimum wages may contribute to more stable employment relationships and commitment to the fi rm, there is a concern that

increases in wages mandated by the government may have weak links to pro-ductivity at enterprise, sector and economy level, and rely too much on cost of living estimates through the KHL. Third, several studies suggest that minimum wages are currently set close to prevailing entry level wages in larger fi rms,

rather than as fl oor wages to protect workers in low-wage fi rms. They therefore

have a much wider impact than merely acting as a safety net for the lowest-paid workers. Potentially, they are likely to discourage employers from taking on unemployed or under-employed workers who might be recruited at much lower, market-clearing rates.

We have discussed the ‘blow-out’ in minimum wages in 2000–01, when aver-age real increases were 20%, and nominal increases closer to 30% for two succes-sive years (Manning 2006). In part, this was an adjustment to sharp declines in the real value of average and minimum wages because of high infl ation during

the crisis. But real wages had already been restored to pre-crisis levels by 2001, and rose signifi cantly above them in the subsequent year (by approximately

15%), during a period of relatively slow economic growth. Wages in large and medium fi rms in manufacturing rose faster than those in the urban informal

sector where employers are less likely to comply with labour legislation, sug-gesting that increases in minimum wages probably had some impact on wage growth in the formal sector.29

Nevertheless, the 2003 law’s provisions on minimum wages include a number of important improvements over the previous legislation. They allow greater fl

ex-ibility for district and provincial governments to set minimum wages in accord-ance with local labour market conditions. Indeed, the coeffi cient of variation in

nominal minimum wages across provinces increased from 0.15 in the pre-crisis and immediate post-crisis period to closer to 0.2 from 2000 onwards. Annual increases were lower on average across provinces from 2003 to 2006 (closer to 5% in 2003–04, and barely above zero in the next two years) compared with the preceding three years. Second, the legislation permits exemptions or postpone-ment of wage adjustpostpone-ments for ‘low productivity’ establishpostpone-ments (regulated by the Ministry of Manpower) and a gradual adjustment of minimum wages to the new levels based on ‘decent’ standards of living. Finally, the involvement of offi cials

from the regional statistical offi ces in the measurement of cost of living increases

is an important step towards a more scientifi c analysis of ‘basic needs’ on which

to base minimum wage increases.

29 See Manning and Roesad (2006) for details of wage increases over the period 2001–06.

Other regulations, and implementation of the law

Many other articles in the Manpower Law dealing with labour protection have long been found in earlier legislation. The law reaffi rms that Indonesia imposes

a 40-hour working week at normal rates of pay, and applies statutory overtime rates (one and one half times normal wages in the fi rst hour of overtime, and

twice these rates for subsequent hours). Although many of these regulations are similar to those in other countries, some are more restrictive. For example, the 40-hour normal working week contrasts with a 44- or 48-40-hour normal working week for many countries at similar stages of economic development. Overtime rates are also high by Asian standards (Felipe and Hasan 2006; ADB 2005: 44–5).

The Manpower Law contains a long section (chapter 9) on industrial relations, dealing with institutional arrangements for setting labour standards. These pro-visions require the formation of ‘a bipartite cooperation forum (literally “institu-tion”)’, involving trade unions and employer representatives, in all fi rms with 50

employees or more, as a mechanism for communication at the enterprise level. ‘Tripartite cooperation forums’ with government, employer and trade union rep-resentatives are also to be created as channels for communication and advice to the government at the national, provincial and district levels.30 All fi rms with 10

or more employees are required to draw up a set of company regulations detailing the rights and obligations of workers, consistent with the law. Collective labour agreements are negotiated for a duration of two years.31

It is very likely that the dominant role of government in setting wage levels will hinder the development of unions and bipartite collective bargaining at the enterprise level. While the Manpower Law includes a major section on collec-tive bargaining, the detailed regulation of minimum wages and other conditions of work severely restricts the number of issues that can be determined through negotiation at the enterprise level, especially since minimum wages set the entry level of remuneration for most employees in larger private sector establishments (Suryahadi et al. 2003).

Dispute resolution is also regulated under the law, including conditions gov-erning the right to strike, although details of the new industrial relations courts are covered in other legislation. Supervision is undertaken by labour inspectors, and it is regulated under separate ministerial decrees and regulations. Criminal sanctions are stipulated for a wide range of violations of the law, especially those related to employment of child, female and foreign workers, to non-payment of severance pay or failure to comply with the minimum wage, to failure to provide a place for religious observance, and to unlawful interference by employers with the right of workers to strike or join a trade union.

30 See Government Regulation 8/2005 for implementing legislation.

31 According to the 2003 Manpower Law, only one collective labour agreement is permitted per fi rm, and trade unions engaged in negotiation of these agreements should represent

at least 50% of all workers, or form a coalition with other unions in the same enterprise to fulfi l this minimum requirement of representation (articles 119 and 120).

PROPOSED CHANGES TO THE MANPOWER LAW

As with all legislation, the 2003 Manpower Law was drafted by the relevant gov-ernment ministry, in this case the Ministry of Manpower. However, unlike the previous, abandoned law of 1997, Law 13/2003 was not enacted by parliament until extensive discussions had been held with major stakeholders, including the employers association Apindo (a branch of the chamber of commerce and indus-try) and the major trade union federations.32 Although dissatisfaction with several

clauses of the law was voiced publicly in debates among the main stakeholders before its enactment,33 there was relatively little debate on its more controversial

provisions until 2005–06. However, labour issues began to receive attention in 2005 in research on problems that appeared to be adversely affecting the invest-ment climate; this was published in a 2006 University of Indonesia report and in World Bank-sponsored surveys. The International Finance Corporation/World Bank publication of internationally comparable data on the diffi culty of doing

business ranked Indonesia high in terms of a range of restrictive employment regulations (IFC 2006).

In early 2005, reform of the law became part of the policy agenda, and the Ministry of Manpower began discussions with unions and employers on possible revisions. In February 2006, reform of the law (together with laws on tax, customs and investment) was offi cially included as a major component of the Investment

Climate Reform Package issued by the Coordinating Ministry of Economic Affairs (Manning and Roesad 2006: 156–7).

In March 2006 the government announced a detailed list of proposals for revi-sion of the Manpower Law. As mentioned earlier, these changes were subsequently put on hold in April–May 2006, mainly as a result of opposition from the union movement.34 It is diffi cult to understand why the president (who announced that

the government would not persevere with its immediate plans to revise the Man-power Law) backed down so quickly when faced with a relatively tame display of opposition by most international standards. It did suggest, however, that there was not a strong commitment to labour market reform on the part of the president or within the economics team. This was refl ected not only in the quick backdown,

but also in the haste with which the reform package had been prepared, and in the lack of a clear political strategy for pushing through a controversial policy change in an area where leadership was needed (Manning and Roesad 2006: 168–9). It is

32 A draft of the new law was fi rst completed by the Wahid government in 2000 and was

circulated for debate among stakeholders.

33 Senior offi cials of the National Development Planning Agency, Bappenas, took a

pub-licly critical stance on several provisions of the law, which was strongly promoted by the Minister of Manpower, Jacob Nua Wea. More radical union leaders such Dita Sari wanted greater protection (see, for example, the interview with Bambang Widianto from Bappenas in Van Zorge Report, 21/8/2002; and the Labor Roundtable featuring the minister, Dita Sari and Bambang Widianto in Van Zorge Report, 8/10/2002.)

34 The vice president announced that there would be no revisions to the Manpower Law (although he did leave the door open for new government regulations on labour issues) following the completion of an ‘independent’ report by a committee of experts from fi ve

universities, made to the Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs in August 2006 (Financial Times, 12/9/2006).

instructive to see which issues had been the focus of business and economic policy maker concerns, as refl ected in the draft revisions to the legislation. Major reforms

were proposed on all three of the issues discussed above: rates of severance pay; sub-contracting and employment of workers on FTCs; and minimum wages.

Severance pay

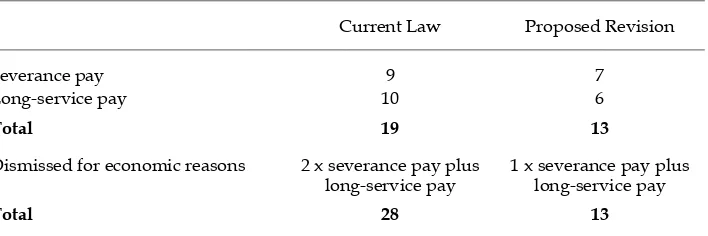

The proposed revisions to Law 13/2003 included a signifi cant reduction in

sev-erance pay rates (table 5).35 Under the proposed reforms, the rates would have

been reduced to a maximum of seven months, compared with nine months under the current law. Long-service pay would also have been reduced to a maximum of six months (10 months under the current law). If a worker was dismissed for economic reasons, the maximum total severance pay (severance plus long-service pay) was to be set at 13 months (28 months under the current law).

Fixed-term contracts and sub-contracting

It was proposed that FTCs could be used for all activities, rather than being lim-ited to certain (seasonal) jobs. Firms would be allowed to hire workers under FTCs for up to fi ve years (previously three years), before transferring them to

permanent status.

With regard to sub-contracting, the ministry recommended that these agree-ments be applied to all types of work and production under the amended law, and not be limited to ‘core production’ activities. Under the proposed amend-ments, sub-contracting arrangements should be specifi ed in a written agreement

between the initiating enterprise and the contracted enterprise or labour supplier. Workers employed in the sub-contracting activity would be required to have a

35 Discussion of the proposed revisions is based on Ministry of Manpower and Trans-migration (2006).

TABLE 5 Maximum Severance and Long-service Pay Rates under Law 13/2003 and Proposed Revised Lawa

(months of pay)

Current Law Proposed Revision

Severance pay 9 7

Long-service pay 10 6

Total 19 13

Dismissed for economic reasons 2 x severance pay plus long-service pay

1 x severance pay plus long-service pay

Total 28 13

a Maximum severance pay rate refers to severance pay for workers with more than 24 years of service.

Source: Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration (2006).

TABLE 6 ‘Hiring and Firing’ Indicators in Selected Southeast Asian Countries, 2006 What is the maximum duration of term contracts (in

months)?

NL 0 NL 0 NL 0 72 0 36 0.5

What is the ratio of the mandated minimum wage to the average value added per worker?

0 0 0.66 0.67 0.18 0 0.19 0 0.26 0.33

Rigidity of hours indexb 20 40 20 40 40

Can the work week extend to 50 hours (including overtime) for 2 months per year?

Yes 0 Yes 0 Yes 0 Yes 0 Yes 0

What is the maximum number of working days per week?

6 0 6 0 6 0 6 0 6 0

Are there restrictions on night work? No 0 Yes 1 No 0 Yes 1 Yes 1 Are there restrictions related to ‘weekly holiday’

work/leave?

Yes 1 Yes 1 Yes 1 Yes 1 Yes 1

What is the paid annual vacation (in working days) for an employee with 20 years of service?

16 0 5 0 6 0 16 0 12 0

Diffi culty of fi ring indexb 10 20 0 70 50

Is the termination of workers due to redundancy legally authorised?

Yes 0 Yes 0 Yes 0 Yes 0 Yes 0

Must the employer notify a third party before termi-nating one redundant worker?

Yes 1 Yes 1 No 0 Yes 1 Yes 1

Does the employer need the approval of a third party to terminate one redundant worker?

No 0 No 0 No 0 Yes 1 Yes 1

Must the employer notify a third party before termi-nating a group of redundant workers?

No 0 Yes 1 No 0 Yes 1 Yes 1

Does the employer need the approval of a third party to terminate a group of redundant workers?

No 0 No 0 No 0 Yes 1 Yes 1

Must the employer consider reassignment or retrain-ing options before redundancy termination?

No 0 No 0 No 0 Yes 1 No 0

Are there priority rules applying to redundancies? No 0 No 0 No 0 Yes 1 No 0 Are there priority rules applying to re-employment? No 0 No 0 No 0 No 0 No 0

Rigidity of employment indexb 10 39 18 37 50

Hiring cost (% of salary) 12.8 8.5 5.2 17 10

What is the notice period for redundancy dismissal after 20 years of continuous employment (weeks of salary)?

8 4.3 4.3 0 0

What is the severance pay for redundancy dismissal after 20 years of employment (months of salary)?

18.5 20 11.5 20 25

What is the legally mandated penalty for redundancy dismissal (weeks of salary)?

0 0 0 0 0

Firing cost (weeks of wages) 88 91 54.3 86.7 108.3

a An adjustment has been made to the Indonesian data on restrictions for night work. The original score in the

IFC database was 0 but should be 1; night work is forbidden for pregnant women and women aged less than 18 years. This affects the total score for rigidity of hours and the total rigidity of employment index.

b A = answer; S = score; NL = no limit. The fi rst three indices measure how diffi cult it is to hire a new worker,

how rigid the regulations are on working hours, and how diffi cult it is to dismiss a redundant worker. Each

index assigns values between 0 and 100, with higher values representing more rigid regulations. The overall rigidity of employment index is an average of the three indices.

Source: IFC and World Bank (2006).