An Application of the Relapse Prevention Model

Barbara A. Stetson, Ph.D. and Abbie O. Beacham, Ph.D. Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences

University of Louisville

Stephen J. Frommelt, Ph.D.

Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation St. Luke’s Medical Center

Kerri N. Boutelle, Ph.D. Department of Pediatrics

University of Minnesota

Jonathan D. Cole, Ph.D. The Pain Treatment Center

Lexington, Kentucky

Craig H. Ziegler, M.S.

Department of Bioinformatics and Biostatistics University of Louisville

Stephen W. Looney, Ph.D. Department of Biostatistics

Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center

ABSTRACT

Background:Key factors in successful long-term exercise maintenance are not well understood. The Relapse Prevention Model (RPM) may provide a framework for this process. Pur-pose:The purpose of this study was to examine the relationships among characteristics of exercise high-risk situations, compo-nents of the RPM relevant to exercise slips, and follow-up exercise outcomes in long-term community exercisers.Methods:We ob-tained long-term exercisers’ (N = 65) open-ended responses to high-risk situations and ratings of obstacle self-efficacy, guilt, and perceived control. High-risk situation characteristics, cogni-tive and behavioral coping strategies, and exercise outcomes were examined.Results:High-risk situation characteristics in-cluded bad weather, inconvenient time of day, being alone, nega-tive emotions, and fatigue. Being alone was associated with lower incidence of exercise slip. Positive cognitive coping strategies were most commonly employed and were associated with positive exercise outcome for both women and men. Guilt and perceived control regarding the high-risk situation were associated with ex-ercise outcomes at follow-up, but only among the men (n = 28). Conclusions:Findings confirm and extend previous work in the application of the RPM in examining exercise slips and relapse. Measurement issues and integration approaches from the study of relapse in addiction research are discussed.

(Ann Behav Med 2005,30(1):25–35)

INTRODUCTION

Physical and psychological health benefits of regular exer-cise are numerous (1,2). On average, physically active people outlive those who are inactive (3,4). Despite these compelling data, rates of regular exercise among healthy adults remain as-tonishingly low, with 25% of adults engaging in no leisure-time physical activity (2). It is estimated that only about 11% of healthy adults engage in moderate-to-vigorous, purposeful ac-tivity 3 or more days per week. Rates of participation in “life-style-based” activity, accumulating 30 min of activity 5 or more days per week are higher but still remain below one fourth of healthy adults (5).

EXERCISE LAPSE AND RELAPSE

A great deal of emphasis has been placed on encourag-ing initiation of physical exercise. However, successful main-tenance of exercise behavior once it has been initiated has not been studied extensively. What constitutes successful “mainte-nance” remains undefined. It has become generally accepted that one enters maintenance after engaging in regular physi-cal activity for a minimum of 6 months after an intervention has been completed or the behavior change has been initiated independent of a formal intervention (6). The vast majority of research in this area has focused on the study of successful ex-ercise initiation and adherence as the cornerstone for main-tenance. Predictors of continued maintenance among long-term exercisers have not been definitively identified (7).

Similar to the management of weight over time, the mainte-nance of exercise becomes a lifelong process. Lapses or “drop out” in exercise routines are quite common and are considered to be more the rule than the exception, reaching as high as 50%

25 Reprint Address:B. Stetson, Ph.D., Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, 317 Life Sciences Building, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY 40292. E-mail: [email protected]

dropout in some populations (8). Sallis et al. (9) suggested that a large proportion of the population may have previously initiated exercise but subsequently relapsed (no exercise for≥3 months) at some later time. In this community-based study of patterns of lifetime history of relapse from exercise, 20% of regular exercis-ers experienced a previous relapse three or more times, 20% re-ported 1 to 2 relapses, and 60% rere-ported no history of relapse. Although injury was reported as the most frequent cause of re-lapse, those who cited lack of interest, low self-efficacy, and /or other unspecified psychological factors were less able to rein-state their exercise programs (9).

Although previous research supports the notion that exer-cise lapse and relapse occurs with some frequency, there is a lack of consensus regarding how exercise lapse or relapse are defined. For example, whereas Sallis et al. (9) defined relapse as a period of no exercise for 3 months or more, Simkin and Gross (10) defined alapseas a 1-week period andrelapseas a 3-week period without exercise. Marlatt and Gordon (11,12) conceptu-alized aslipin smoking cessation as smoking one or more ciga-rettes in a specific situation. Similarly, an exercise slip may be viewed as an acute isolated missed exercise session. In this in-stance, the slip and how a slip is perceived may be regarded as the gateway to lapses and/or relapses or more prolonged seden-tary periods during which time persons do not engage in planned exercise.

PREDICTION OF EXERCISE RELAPSE

The Relapse Prevention Model (RPM) (11,13,14) has been used extensively in the study of addiction and substance abuse (11,12). This conceptual model addresses the cyclical nature of long-term behavior change. It provides a valuable framework for understanding factors related to slips, lapses, and relapse in exercise behavior among persons who are considered long-term exercisers. According to the RPM, higher probabilities for re-lapse occur when an individual with inadequate coping skills is faced with a “high-risk” situation. Coping behavior plays an im-portant role in understanding the relationship between exposure to challenging situations and outcome (i.e., slip, lapse, or re-lapse). Within the addictive behaviors literature utilizing the RPM, coping “refers to what an individual does or thinks in a relapse crisis situation so as to handle the risk for renewed substance use” (15, p. 1101) and coping is conceptualized as a mediator between the stress of the high-risk situation and relapse (15).

According to the RPM, it is the person’s coping response(s) that will determine whether a slip will occur subsequent to en-countering a high-risk situation. Coping efforts are predomi-nately linked to a desired goal (e.g., attending a planned exercise session) and may be cognitive, behavioral, or a combination thereof (16,17). Studies examining coping in relation to lapse in exercise or dietary adherence have defined coping strategies in accordance with cognitive and behavioral parameters (10,17). Within the RPM, an inadequate repertoire of adaptive coping re-sponses results in lower self-efficacy for overcoming obstacles in high-risk situations.

In the exercise literature to date, coping in the face of obsta-cles to exercise has not been examined with regard to individu-als’ exercise history or gender. In the general coping literature, gender differences have been examined. A meta-analysis of em-pirical studies evaluating coping behaviors in the context of spe-cific situations (18) suggested that women had higher rates of engaging in most types of coping strategies. Findings indicated that women were more likely to use active coping, seek instru-mental social support, and use more problem-focused coping. Women were also more likely to seek emotional support, use avoidance, engage in positive reappraisal, ruminate, engage in wishful thinking, and employ positive self-talk. Some gender differences were dependent on the nature of the stressor—for example, personal health, others’ health, achievement, and rela-tionship stressors.

An additional study of men and women citing high levels of work or marital stress compared self-reported coping on questionnaires and prospective electronic diary ratings (19). Cross-sectional assessment found that women reported higher levels of coping via social support and catharsis compared to men. These studies suggest that there are gender differences in the use of coping strategies; however, findings may be influ-enced by stressor appraisal, perceived controllability, or assess-ment methodologies.

Another important aspect of the RPM is the self-efficacy construct. Decreased self-efficacy for exercise combined with positive outcome expectancy for a slip may increase its proba-bility. For example, if one rationalizes “I’ll have more time and energy if I skip exercise tonight,” there is an increased probabil-ity of missing a planned exercise session. An Abstinence Viola-tion Effect then ensues in which increased feelings of guilt and perceived loss of situational control further contribute to the probability of a full-blown relapse or return to the unhealthy (i.e., sedentary) behavior for an extended period of time. The Abstinence Violation Effect has two component parts: one’s causal attributions for a slip and the affective (i.e., guilt) reaction to the attribution (20). The Abstinence Violation Effect is con-sidered to be a particularly powerful determinant of the course of a possible lapse or relapse.

One difficulty in understanding the impact of relapse pre-vention interpre-ventions aimed at producing and maintaining be-havior change is the general lack of studies attempting to empir-ically evaluate the utility of the model. For a comprehensive overview of the RPM, we refer the reader elsewhere (13). Appli-cation of the RPM in exercise behavior has produced inconsis-tent findings, creating some uncertainty about its pertinence to exercise behavior (21). Previous studies have examined RPM as it relates to exercise adherence by including relapse prevention components in interventions conducted with previously seden-tary samples with mixed results (22,23). Furthermore, the lim-ited number of studies applying the RPM have typically been plagued with a variety of methodological limitations (21).

prospectively over a 14-week period among previously seden-tary healthy young women. A series of vignettes of commonly encountered high-risk situations were presented to the study participants. The vignettes presented empirically derived themes in high-risk situations including negative mood, lack of time, bad weather, fatigue, social situations, and boredom. These findings were consistent with high-risk situational char-acteristics identified in the larger relapse prevention literature (13). Cognitive and behavioral coping strategies and subsequent relapse in response to commonly encountered situations posing interference with planned exercise were examined. The rate of exercise lapse was higher among women who cited fewer num-bers of coping strategies at their disposal. The women in the sample tended to use behavioral coping more than cognitive strategies when presented with high-risk scenarios. Use of be-havioral coping was related to higher levels of fitness at 3-month follow-up.

Belisle, Roskies, and Levesque (24) conducted a series of two studies utilizing the RPM as part of an exercise adherence intervention. Participants consisted of both men and women. The intervention included components focusing on improving recognition and awareness of barriers to exercise and adaptive coping responses, including information about recognizing and overcoming the Abstinence Violation Effect. Effects of the in-tervention were examined for differences in short-term (i.e., ad-herence throughout the intervention phase) and longer term adherence (i.e., 12 weeks postintervention). Exercisers in the condition including the RPM components exercised more days in both the short- and long-term phases of each of these studies.

In both of these studies, participants were university stu-dents (as opposed to community-based samples), and exercise was followed for a comparatively short period of time. In the first study reviewed, Simkin and Gross (10) classified par-ticipants as “exercisers” based on a self-reported self-schema descriptor as exerciser or nonexerciser. Frequency, intensity, and duration of participants’ exercise were not reported. Therefore, the degree to which the sample met behavioral exercise guide-lines was not clear. Belisle et al. (24) were able to report more objective measures of exercise participation during participants’ enrollment in exercise courses. Study participants’ exercise pat-terns were followed for periods of 10 (24) and 14 (10) weeks af-ter initiation of the exercise inaf-tervention.

Marcus and Stanton (22) conducted a three-arm random-ized intervention study with 120 previously sedentary women. The majority of participants were overweight. A structured re-lapse prevention program was compared to a reinforcement pro-gram and an exercise-only control group. The primary aim of the study was to evaluate the interventions’ impact on session at-tendance. The relapse prevention condition focused on identifi-cation of personal high-risk situations on and group discussions of effective and ineffective coping strategies for managing high-risk situations. A 10-day planned break from exercise was included as a planned relapse to demonstrate that participants could lapse and then resume exercise. A 2-month follow-up as-sessment of exercise frequency, intensity, and duration via par-ticipant and collateral self-report was also conducted. Exercise

leaders for the study were advanced undergraduate students. During the first half of the study, attendance was higher for relapse prevention program participants. However, low atten-dance was a substantial problem encountered across conditions, and attrition was high (72%) by the end of the study. No group differences were observed for posttreatment or follow up. The authors offered methodological improvements of randomized design, longer duration of intervention, follow-up assessment, and conservative definition of program adherence. However, the nature of the sample (overweight university employees led by university undergraduates) and characteristics of the interven-tion (set days and times; aerobic dance) may have influenced the observed attrition rates. With intermittent attendance, partici-pants may not have been exposed to the full complement of Re-lapse Prevention Program content.

A greater understanding of mechanisms of exercise behav-ior change and maintenance of change is needed (25). Support for theoretically driven mediators of exercise behavior change has been mixed (25–27). Previous studies examining relapse in exercise have tended to utilize samples from clinical pop-ulations, university classes, fitness programs, or previously sed-entary persons (7,9). In addition, components of the RPM typi-cally have been examined independently or following an exercise intervention. To our knowledge, the RPM has not been examined in a community sample of long-term exercisers.

be associated with lower physical activity level at the 3-month follow-up.

METHOD Participants

Study participants were recruited from two YMCA exercise facilities in a large midwestern city. Fliers describing the study were posted throughout facilities. Interested individuals con-tacted the investigators by telephone and subsequently com-pleted phone screenings. Adults who were already engaged in exercise and who were free from any serious health complica-tions were eligible to participate. All participation, including in-formed consent, was conducted via U.S. mail.

Procedure

Participants (N= 65) were mailed a baseline survey con-taining questions about demographic and exercise history as well as current physical activity patterns. Questions designed to assess exercise-specific cognitions and perceptions regarding exercise maintenance were also included. Upon return of the baseline survey, participants were mailed an exercise-related high-risk situation questionnaire that assessed personal experi-ence with a self-identified situation that previously posed high risk for an exercise slip. Following completion of the high-risk situation questionnaire, participants were contacted 3 months later to assess ongoing exercise patterns. This study includes re-sults obtained from the baseline demographic/exercise ques-tionnaires and cognitions, assessment of the high-risk situation, and 3 month postbaseline follow-up. Participants were compen-sated as follows: (a) $10 baseline survey completion, (b) $10 for exercise high-risk situation questionnaire completion, and (c) entry into a $100 lottery pool upon completion of follow-up.

Measures

Baseline exercise history. The Exercise and Health His-tory Questionnaire (EHHQ) developed by Dubbert, Stetson, and colleagues (28–30) was used to obtain information on self-re-ported history of exercise and current exercise pattern. The items included (a) exercise history (total months engaged in reg-ular exercise), (b) frequency (average number exercise ses-sions/week), and (c) duration (minutes/session). Validity of this measure was examined in a pilot study of a sample of 196 com-munity exercisers recruited from an urban YMCA, comcom-munity activity centers, and university undergraduates (ethnicity = 77.6% White;Mage = 35.95,SD= 18.90 [unpublished data]). A composite of these three items was compared to the score on the Godin Leisure Time Questionnaire (31). Pearson correlations were .573 (p< .0001), indicating a moderately high degree of association between these EHHQ items and the previously vali-dated activity measure. Two-week test–retest of this exercise measure with a subsample (n= 83) of participants yielded a cor-relation of .255 (p= .020). One-week test–retest reliability was also evaluated in another pilot study with a sample of 29 college students (r ≥.90).

Participants were also asked, “Rate how hard you typically work when you exercise.” A subjective rating of “typical” per-ceived exertion (RPE) during exercise sessions was obtained us-ing the 6 (very, very light) to 20 (very, very hard) Borg RPE Cat-egory scale (32,33). Reliability coefficients for this scale in submaximal exercise have ranged from .70 to .90 (34). The ret-rospective use of RPE in this study may be likened to a com-monly used practice of perceptually regulated exercise intensity (35), and in the absence of available direct physical fitness mea-sures, the derivation of exercise indexes may be regarded as an acceptable surrogate measure of physical activity (36).

Exercise cognitions and perceptions. Self-efficacy for over-coming obstacles and engaging in exercise was also examined (35,37). Participants listed their top personal obstacle to regular exercise and rated confidence for overcoming the corresponding obstacle on a 0 (I will not be able to overcome this and exercise) to 100% (I will be able to overcome this and exercise) confi-dence scale. Single item self-efficacy measures have been suc-cessfully used in the study of smoking and the RPM to identify smoking lapses and relapse following lapse (38). Zero to 100% ratings of obstacle self-efficacy have been found to be related to exercise adherence and drop out in beginning and consistent ex-ercisers (39–41) and are consistent with Bandura’s recommen-dations for measuring self-efficacy (39,42,43). The top exercise obstacles were self-generated by participants. The self-efficacy ratings for self-reported top obstacles were used in analyses, in keeping with recommendations to include personal, salient bar-riers that are anticipated to occur frequently in assessing obsta-cle efficacy (39). Self-determination of status as a regular or in-termittent exerciser was assessed dichotomously.

Self-identified high-risk situation. Each participant was asked to describe a high-risk situation of recent personal experi-ence in which he or she had planned on exercising and had felt most tempted to not engage in the exercise. Participants were in-structed to “imagineone specific situationwhere you felt you should exercise but felt tempted not to.” Additional items posed specific questions to elicit description of the characteristics of the situation. Participants described these characteristics using an open-ended response format. A sample high-risk situation described by a participant is presented to provide an example of a specific situation: “I was in my car heading for the gym with all good intentions.” “It was after a very stressful day at work, I hadn’t had enough sleep, traffic was bad and the weather was overcast and cold.”

posi-tive, negaposi-tive, or neutral mood. The exercise outcome of the situation was assessed dichotomously—that is, “How did this situation turn out—did you exercise or not?”

Three independent raters were trained in the coding of the high-risk situation characteristics. Coding instructions specifi-cally guided raters to make their coding decisions independent of exercise outcome in the high-risk situation. Following calcu-lation of coefficient kappa, any disagreements on items were re-solved via mutual agreement of the raters.

Abstinence Violation Effect. Cognitive and behavioral as-pects of the response to the high-risk situation and outcome (i.e., Abstinence Violation Effect) included ratings of guilt about the outcome and perceived control in managing the temptation to not exercise.

Coding of coping responses. Coping responses were con-ceptually organized into two dimensions: cognitive coping re-sponses and behavioral coping rere-sponses. Coding criteria were developed based on Marlatt’s studies of coping with high-risk drinking situations (13) and a review of the stress and coping lit-erature (16,44–46). As in previous studies assessing coping strategies, cognitive coping was defined as nonobservable thought processes. Behavioral coping strategies were those which could be observed (17,47).

Coding criteria reflected three cognitive coping ap-proaches: task-oriented problem solving, positive reappraisal, and rationalization. Task-oriented problem-solving ratings re-flected thought processes addressing strategies for overcoming obstacles. Positive reappraisal ratings reflected use of positive self-statements and cost–benefit analysis. Both coping strate-gies were regarded as positive approaches. Regarded as a nega-tive approach, rationalization ratings reflected personal bargain-ing and justifybargain-ing reasons not to exercise.

Coding criteria reflected three behavioral coping ap-proaches: engaging in pre-exercise rituals, eliciting social sup-port, and engaging in procrastination or avoidance. Engaging in pre-exercise rituals ratings reflected engaging in a routine to pave the way for exercise (e.g., laying out exercise clothes in advance). Eliciting social support ratings reflected seeking the assistance of others to facilitate exercise. Procrastination and avoidance ratings reflected creating self-imposed barriers to ac-tivity and engaging in other activities until the window of oppor-tunity expired (e.g., no time left, dark outside).

Three independent raters were trained in the coping coding scheme. Responses to each of the coping questionnaire items were subsequently coded. Coding instructions specifically guid-ed raters to make their coding decisions independent of exercise outcome in the high-risk situation. Following calculation of co-efficient kappa, any disagreements on items were resolved via mutual agreement of the raters.

Exercise characteristics at 3-month follow-up. Three months after the completion of the baseline survey, participants were mailed a brief follow-up exercise questionnaire regarding their activity over the previous month. The 3-month follow-up is

con-sistent with the two reviewed studies utilizing the RPM in exer-cise (10,24). Previous work in exerexer-cise adoption suggests that rates of exercise drop out have substantial magnitude in a 3-month window (8), and therefore this time frame may provide an infor-mative snapshot of the maintenance process . Participants rated their perception of their current exercising status as maintaining exercise or not regularly exercising. Exercise items were consis-tent with those administered at baseline, including frequency (av-erage number of exercise sessions/week), duration (min/session) and perceived exertion (RPE) during exercise sessions during the previous month (32,33). Participants also listed current personal obstacles to regular exercise and rated confidence for overcoming the corresponding obstacle on a 0 to 100 confidence scale (48).

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows®, Version 11.0. Odds ratios were used to measure association be-tween dichotomous outcome and predictor variables. Logistic regression was used to examine the effect of confounding vari-ables for dichotomous outcomes. Pearson correlations were used to measure association between continuous outcomes and predictors. Point biserial correlation was used to measure asso-ciation between dichotomous outcomes and continuous predic-tors. Partial correlation (pr) and multiple regression were used to examine the effect of confounding variables for continuous outcomes. Stepwise variable selection was used to determine the best set of predictors for both the logistic and multiple re-gression models.Ttests were used to test for significant differ-ences in means between two groups. Fisher’s exact test was used to test for differences in proportions between groups. Because the majority of studies utilizing the RPM across the addictive and health behavior literatures have been with single gender samples, and because gender differences have been observed in physical activity levels and use of coping strategies, it was hy-pothesized that the gender of participants might impact study outcomes. Therefore, analyses were stratified by gender wher-ever appropriate. The Breslow–Day method was used to test for significant differences across strata. Two-tailed tests were used for all analyses. An alpha level of .05 was used as the criterion for statistical significance.

RESULTS Participant Demographic Characteristics

BMI women = 24.3,SD= 8.7). No differences between genders were observed in these background characteristics.

Interrater Reliability for Coding of High-Risk Situation Characteristics

Kappa coefficients for the characteristics of the high-risk situation (weather, time of day, social context, physical state, mood) were all significantly different from 0, with moderate high to high magnitude (κ= .86 for weather, .75 for time of day, .92 for social context, .75 for mood, .85 for physical state).

Interrater Reliability for Coding of Coping Responses

Kappa coefficients were high across each of the coping cat-egories, indicating strong interrater agreement. Kappas for each of the coping categories were as follows: task/problem solving, .84; positive reappraisal, .83; rationalization, .88; procrastina-tion/avoidance, .86; pre-exercise rituals, .95; social support, .98.

Baseline Analyses

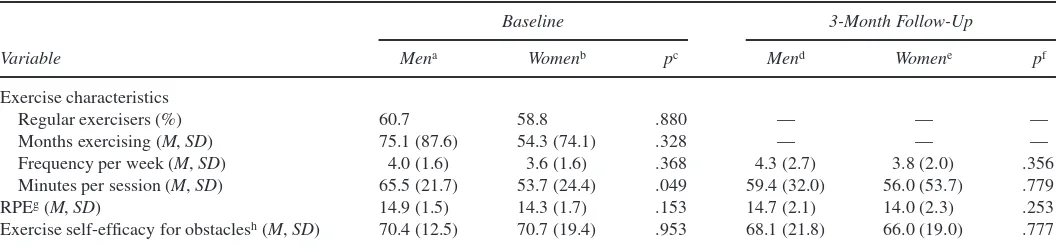

Baseline exercise patterns and perceptions. Baseline ex-ercise characteristics by gender are presented in Table 1. On av-erage, participants reported maintenance of regular exercise for approximately 5 years, with some participants reporting over 20 years of regular exercise. Participant ratings of perceived exer-ciser status indicated that 61.8% of the sample rated themselves as “regular” exercisers, whereas 38.2% perceived themselves to be “intermittent.” Participants averaged 3 to 4 days per week of activity. Typical exercise sessions averaged nearly 1 hr. Ratings of perceived exertion during exercise sessions tended to be “moderate” or “somewhat hard.” Women reported exercising for significantly fewer minutes per session than men.

RPM Variables

High-risk situations. The most commonly cited character-istics of the high-risk situations were similar for both men and women, including bad weather (75% and 66.7%, respectively), occurrence in the morning (53.8% and 43.8%, respectively),

be-ing alone (75% and 59.5%, respectively), a negative mood (54.5% and 70.6%, respectively), and being physically tired (62.5% and 60.0%, respectively; allps >.05). Of the 64 partici-pants who characterized their high-risk situation, 4 (6.1%) listed one characteristic, 13 (19.7%) listed two, 14 (21.2%) listed three, 18 (27.3%) listed four, 14 (21.2%) listed five, and 3 (4.5%) listed six. The mean number of characteristics listed for the high-risk situation was 3.5 (SD= 1.3). No gender differences were found in the high-risk situation characteristics.

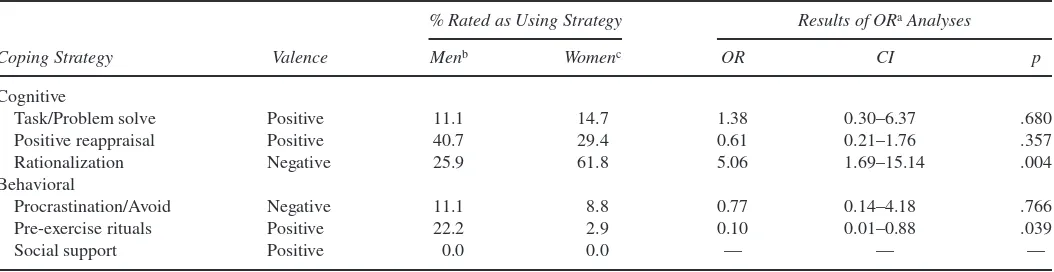

Coping strategies employed in high-risk situations. Positive cognitive coping strategies were used by 42.9% of participants. This included use of positive reappraisal by 35.4% of partici-pants (e.g. “I reminded myself I’ve had some of my best runs when I didn’t feel like it”) and task/problem solving by 12.3% (e.g., “I decided to drive towards the gym. … I told myself I did-n’t have to exercise that long”). The negative cognitive coping strategy of rationalization was used by 47.6% of participants (e.g., “I thought, I’ll exercise tomorrow, my figure won’t be that much worse if I miss today”). Of those employing positive cog-nitive strategies, only 3.1% used more than one type of positive cognitive strategy in the high-risk situation. Given this small number, the positive cognitive strategies variable was recoded to reflect a dichotomous rating (used vs. did not use) in all subse-quent analyses. Percentages of participants reporting use of in-dividual cognitive coping strategies are presented in Table 2. Women were significantly more likely to use rationalization in the high-risk situation than men. Positive behavioral strategies were represented entirely by use of pre-exercise rituals (e.g., “I laid out my exercise clothes and just started dressing for it … washed my face, took two Ibuprofen … ”). None of the partici-pants reported using solicitation of social support in response to the high-risk situations. The negative behavioral strategy of pro-crastination was exemplified by putting off the planned exercise (e.g., “I thought, I’m so tired, I’ll just make a few phone calls first”). No participant used more than one type of behavioral coping strategy. Men were significantly more likely to use pre-exercise rituals in the high-risk situation than women. Only two participants used a combination of both cognitive and

be-TABLE 1

Self-Reported Exercise Characteristics at Baseline and 3-Month Follow-Up Compared by Gender

Baseline 3-Month Follow-Up

Variable Mena Womenb pc Mend Womene pf

Exercise characteristics

Regular exercisers (%) 60.7 58.8 .880 — — —

Months exercising (M,SD) 75.1 (87.6) 54.3 (74.1) .328 — — —

Frequency per week (M,SD) 4.0 (1.6) 3.6 (1.6) .368 4.3 (2.7) 3.8 (2.0) .356

Minutes per session (M,SD) 65.5 (21.7) 53.7 (24.4) .049 59.4 (32.0) 56.0 (53.7) .779

RPEg(M,SD) 14.9 (1.5) 14.3 (1.7) .153 14.7 (2.1) 14.0 (2.3) .253

Exercise self-efficacy for obstaclesh(M,SD) 70.4 (12.5) 70.7 (19.4) .953 68.1 (21.8) 66.0 (19.0) .777

Note. RPE = rating of perceived exertion.

havioral strategies (one man and one woman). Given this small number, combined use of these approaches was not included in any subsequent analyses.

Self-efficacy for overcoming obstacles in a high-risk situa-tion. Self-efficacy for overcoming top personal exercise obsta-cles was well above the midpoint of the 100-point confidence scale (M= 71.5,SD= 18.9). There were no gender differences in self-efficacy for overcoming exercise obstacles.

Exercise slip in a high-risk situation. Participants were near-ly evennear-ly split in the outcome (i.e., slip) of the high-risk situation (46.2% exercised, 53.8% slipped). However, women were al-most twice as likely to report a slip (63.9% did not exercise) than were men (37.0% did not exercise); this is equivalent to an odds ratio of 3.01 (95% CI = 1.07–8.47,p= .037).

Self-efficacy versus high-risk situation outcome. Baseline self-efficacy for overcoming obstacles was also examined in re-lation to exercise slip in the self-identified high-risk situations. No significant associations were observed for either gender.

Exercise pattern versus high-risk situation outcome. For both men and women, more intermittent exercisers experienced a slip than did regular exercisers, and the test for homogeneity of odds ratios across strata indicated no difference in odds ratio be-tween men and women (p = .170). Therefore, the men and women were pooled to calculate an overall estimate of the odds ratio (OR = 2.95, 95% CI = 0.99–8.77,p= .052). Because this association is so close to being statistically significant, a dummy variable indicating whether the participant was a regular or in-termittent exerciser was considered as a potential confounding variable in the multivariate analyses.

Characteristics of high-risk situation versus high-risk situ-ation outcome. The only characteristic of the high-risk situa-tion that was significantly associated with an exercise slip was being alone; for both men and women, participants who were alone during the high-risk situation were less likely to slip. The

test for homogeneity of odds ratios across strata indicated no difference in odds ratio between men and women (p= .896); therefore, the men and women were pooled to calculate an over-all estimate of the odds ratio (OR = .29, 95% CI = 0.09–0.93,p= .038). There was no significant difference in the number of char-acteristics of the high-risk situation between those who slipped and those who did not.

Abstinence Violation Effect. High-risk situations and out-comes were significantly associated with guilt and perceived control. Patterns of association differed by gender. Women re-ported higher levels of guilt in response to the high-risk situation compared to men (M= 4.30, SD = 1.85 vs.M= 3.07,SD= 1.98 , respectively),t(63) = 2.564,p=.013. However, women and men did not differ in perceived loss of control regarding the exercise outcome. Women who reported a slip had higher guilt ratings than women who reported exercising in the high-risk situation (M= 4.78, SD = 1.48 vs.M= 3.46,SD= 2.26),t(34) = 2.125,p= .041. For women, perceived control ratings did not differ be-tween those who slipped and those who exercised. Men who re-ported a slip in the high-risk situation had far higher guilt ratings than men who reported exercising (M= 5.10,SD= .57 vs.M= 1.94,SD= 1.56),t(25) = 6.13,p< .001. Men who reported slip-ping in the high-risk situation also had lower ratings of per-ceived control compared to men who reported exercising (M= 4.00,SD= 1.73 vs.M= 5.65,SD= 1.27),t(24) = –2.77,p= .011.

Coping strategies employed and high-risk exercise situa-tion outcome. The relationship between use of coping strate-gies and exercise outcome (exercise vs. slip) in the high-risk sit-uation was examined using odds ratios. The two positive cogni-tive coping strategy categories (task/problem solving and positive reappraisal) were pooled to create a single positive cog-nitive coping variable. Similarly, the two positive behavioral coping strategies (pre-exercise rituals and social support) were pooled to create a single positive behavioral coping variable. For men, 38.5% of those not reporting use of positive cognitive cop-ing strategies slipped, whereas 100% of those reportcop-ing use of these strategies exercised (OR = 31.18, 95% CI = 3.95–∞,p<

TABLE 2

Rated Use of Exercise Coping Strategies in High-Risk Situations

% Rated as Using Strategy Results of ORaAnalyses

Coping Strategy Valence Menb Womenc OR CI p

Cognitive

Task/Problem solve Positive 11.1 14.7 1.38 0.30–6.37 .680

Positive reappraisal Positive 40.7 29.4 0.61 0.21–1.76 .357

Rationalization Negative 25.9 61.8 5.06 1.69–15.14 .004

Behavioral

Procrastination/Avoid Negative 11.1 8.8 0.77 0.14–4.18 .766

Pre-exercise rituals Positive 22.2 2.9 0.10 0.01–0.88 .039

Social support Positive 0.0 0.0 — — —

Note. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

.001). For women, 90.9% of those not reporting use of positive cognitive coping strategies slipped, whereas 84.6% of those re-porting use of these strategies exercised (OR = 44.29, 95% CI = 5.27–721.49,p< .001). Use of positive behavioral coping strate-gies was not associated with outcome in the high-risk situation for either gender.

The independent effect of use of positive cognitive coping was examined using multiple logistic regression. The positive cognitive coping variable, along with the positive behavioral coping variable and a dummy variable indicating whether the participant was a regular or intermittent exerciser, were entered into a stepwise logistic regression model with the dichotomous exercise outcome (slipped or exercised) as the dependent vari-able. This analysis indicated that there were no additional signif-icant predictors of the high-risk situation outcome other than use of positive cognitive coping strategies. In particular, there was no significant confounding effect of exercise pattern (regular vs. intermittent exercisers) on this association for either gender.

Exercise patterns at 3-month follow-up. Three men and three women (9% of the total sample) did not return activity questionnaires at follow-up. Participants who dropped out did not differ from those who returned the 3-month follow-up sur-vey in terms of duration of maintenance of regular exercise, baseline frequency, and duration of activity, or self-character-ization as an intermittent or regular exerciser. Coping strategy ratings were associated with drop-out status. All participants

rated as using the cognitive reappraisal coping strategy com-pleted follow-up, and all participants rated as not using this coping strategy dropped out. No other coping strategy ratings were associated with drop out. Exercise self-efficacy, slip out-come in the high-risk situation, and Abstinence Violation Effect variables were not associated with drop out at the 3-month fol-low-up.

Of the 59 follow-up respondents, three (two men and one woman) reported that they were not regularly exercising. Partic-ipant exercise patterns and self-efficacy at the 3-month fol-low-up are included in Table 1. These prospectively assessed activity variables did not differ significantly from their corre-sponding baseline indexes and did not differ by gender.

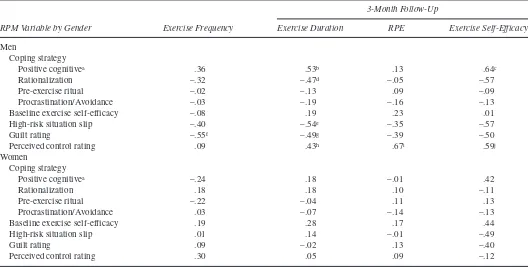

Baseline self-efficacy and exercise at follow-up. Baseline self-efficacy was not associated with any of the exercise mea-sures at the 3-month follow-up for either gender (Table 3).

High-risk situation responses and activity at follow-up. Participant responses to the self-reported high-risk situations were associated with some of the exercise measures at the 3-month follow-up, but only among the men (Table 3). Exercise slip in the high-risk situation was negatively associated with fol-low-up duration of exercise sessions after controlling for base-line duration of exercise. Use of positive cognitive coping strate-gies was positively associated with duration of exercise sessions at follow-up after controlling for baseline exercise duration and

TABLE 3

Associations of Relapse Prevention Model Variables and Exercise Outcomes at 3-Month Follow-Up

3-Month Follow-Up

RPM Variable by Gender Exercise Frequency Exercise Duration RPE Exercise Self-Efficacy

Men

Coping strategy

Positive cognitivea .36 .53b .13 .64c

Rationalization –.32 –.47d –.05 –.57

Pre-exercise ritual –.02 –.13 .09 –.09

Procrastination/Avoidance –.03 –.19 –.16 –.13

Baseline exercise self-efficacy –.08 .19 .23 .01

High-risk situation slip –.40 –.54e –.35 –.57

Guilt rating –.55f –.49g –.39 –.50

Perceived control rating .09 .43h .67i .59j

Women

Coping strategy

Positive cognitivea –.24 .18 –.01 .42

Rationalization .18 .18 .10 –.11

Pre-exercise ritual –.22 –.04 .11 .13

Procrastination/Avoidance .03 –.07 –.14 –.13

Baseline exercise self-efficacy .19 .28 .17 .44

High-risk situation slip .01 .14 –.01 –.49

Guilt rating .09 –.02 .13 –.40

Perceived control rating .30 .05 .09 –.12

Note. Partial correlations, controlling for baseline activity pattern or baseline exercise self-efficacy, where appropriate. RPM = Relapse Prevention Model; RPE = rating of perceived exertion.

with self-efficacy at follow-up after controlling for baseline self-efficacy. Use of rationalization (a negative cognitive coping strategy) was negatively associated with exercise duration after controlling for baseline duration. Use of behavioral coping strat-egies was not associated with follow-up self-efficacy or exercise behavior for either gender.

Abstinence Violation Effect and activity at follow-up. At 3-month follow-up, Abstinence Violation Effect variables—guilt and perceived control—were associated with some exercise pat-terns, but only among the men (Table 3). Guilt regarding the high-risk situation was negatively associated with exercise dura-tion at follow-up after adjusting for baseline exercise duradura-tion, and with typical frequency of exercise at follow-up after adjusting for baseline frequency of exercise. Perceived control over the high-risk situation was positively associated with follow-up exer-cise duration after adjusting for baseline exerexer-cise duration, with follow-up RPE after adjusting for baseline RPE, and with fol-low-up self-efficacy after adjusting for baseline self-efficacy.

The relationship between RPM variables and each of the follow-up exercise measures (typical weekly frequency of exer-cise, duration per exercise session, rating of perceived exertion, and self-efficacy for overcoming exercise obstacles) was exam-ined using multiple regression. A separate stepwise regression analysis was performed with each exercise measure as the de-pendent variable, and use of a positive cognitive coping strategy, use of rationalization, use of a behavioral coping strategy, guilt rating, perceived control rating, the baseline value of the DV, and dummy variables indicating whether the participant slipped in the high-risk situation and whether the participant was a regu-lar or intermittent exerciser as independent variables. For men, guilt rating was associated with exercise frequency at follow-up (n= 23,p= .004), high-risk situation slip status was associated with exercise duration at follow-up (n= 22,p= .022), perceived control rating (n= 22,p< .001), and baseline RPE (n= 22,p= .046) were associated with RPE at follow-up and use of a posi-tive coping strategy was associated with exercise self-efficacy at follow-up (n= 13,p= .022). For women, baseline exercise fre-quency was associated with exercise frefre-quency at follow-up (n= 31,p< .001), and baseline RPE was associated with RPE at fol-low-up (n= 31,p= .004).

DISCUSSION

Consistent with Marlatt and Gordon’s (11) model, use of positive coping responses was associated with reduced likeli-hood of a slip. Positive behavioral strategies were not associated with slips or any exercise maintenance outcomes. Our results provide support for the RPM’s contention that exposure to spe-cific high-risk situations per se does not precipitate slips and re-lapse; rather, it is the manner in which individuals cope with the situations that impacts outcome.

Many or our findings were consistent with the RPM model. Reported exercise slips were associated with Abstinence Viola-tion Effect variables. Both men and women who reported slips reported higher guilt ratings compared to their same gender peers who did not slip. Among the men, those who slipped had

lower perceived control and slip was associated with shorter ex-ercise duration at follow-up. Abstinence Violation Effect variables were associated with exercise at the 3-month fol-low-up, but only among the men.

Although our findings generally support the utility of the RPM in the study of exercise behavior in men and women who are ongoing exercisers, a series of interesting gender differences emerged. Women in our sample were almost twice as likely as men to miss an exercise session or slip in the face of a high-risk situation. This finding could reflect greater prevalence of men maintaining regular exercise in the adult population (2). On the other hand, this gender difference may have been partially af-fected by a self-report artifact in that women may simply be more likely to report a slip than their male counterparts. Women also endorsed higher levels of guilt than men, which may reflect greater affective response to a slip.

Consistent with findings from studies of gender differences in coping, suggesting differences in use of verbal expression to self or others, women in this study had higher use of rationaliza-tion in high-risk exercise situarationaliza-tions than did men. Conversely, higher use of the behavioral coping (pre-exercise rituals) among the men was an unexpected finding. In addition, some similari-ties among men and women emerged. Neither gender reported using social support as a coping strategy. Among both genders, the use of positive cognitive coping strategies (positive reap-praisal, task/problem-focused coping) was strongly associated with exercising in high-risk situations.

Self-efficacy to overcome exercise obstacles was not pre-dictive of exercise outcome in the high-risk situation for either gender, which may reflect that barrier efficacy in the high-risk situation may be context specific (49). Our single-item self-effi-cacy measure may not have tapped barrier effiself-effi-cacy or variations relative to the high-risk situation. Although not assessed in this study, self-efficacy may be moderated by outcome expectancies for that situation and subsequently moderated by Abstinence Vi-olation Effect variables (i.e., guilt and perceived control). Shiff-man and colleagues (38) suggested that the self-efficacy/relapse relationship is a dynamic and complex process and does not sup-port the hypothesis that lowered self-efficacy precedes and helps to cause lapses. Modest decreases in self-efficacy following an initial lapse may predict subsequent relapse. This hypothesis implies that diminished self-efficacy after an exercise slip may be associated with subsequent lapse and relapse. This is sup-ported by the finding that for the men in our sample, slips in the high-risk situation approached significant association with low-er levels of exlow-ercise obstacle self-efficacy at follow-up (pr = –.57,p= .052). Future studies examining exercise obstacle effi-cacy may be enhanced by use of multiple item scales and re-peated assessments of self-efficacy.

lim-ited. Further, the physical activity outcomes consisted only of typical exercise frequency, intensity, and duration, thus limiting the comparability of our findings to other published studies. More commonly used physical activity assessment instruments over discrete periods of time may reflect a more comprehensive picture of physical activity patterns.

In the absence of an experimental or prospective design, we rely on either hypothetical vignettes or retrospective recall (10,24). In our case, we relied on participants’ retrospective recall. There has been a great deal of discussion regarding the accuracy of ret-rospective recall and the reporting of accompanying cognition and behavior (50). Tennen, Affleck, Armeli, and Carney (51) presented a review of the nature of coping as a process, assessed more accurately with multiple levels of daily assessment. Real-time monitoring of lapses has been successfully applied in the smoking (38,50) and diet maintenance literature. Use of pro-spective, real-time monitoring to assess activity-related cog-nitions may improve on study methodology and permit exami-nation of the dynamic relationships among model components. Measures reflecting the Abstinence Violation Effect and the single-item measure of exercise self-efficacy were developed for this study. Additional evaluation of their reliability and validity are warranted. Limitations of the coping measure utilized include a lack of specific instructions to indicate to a participant that he or she could provide more than one example, as well as a lack of sample coping responses. This approach may have limited the number and type of coping strategies generated by participants.

Exercise maintenance studies would benefit from an exami-nation of the relationships among cognitive, behavioral, and en-vironmental constructs and the reciprocal process by which they exert influence on exercise adoption and maintenance. The fo-cus of this study was on long-term exercisers, including those who exercise regularly and intermittently. However, regular ver-sus intermittent exerciser status did not emerge as a confounding variable in the multivariate analyses conducted in this study. A more exhaustive examination of factors related to exercise pat-terns among those who are well into the maintenance phase as compared to those who have recently adopted exercise, or are relatively early in the adoption process (e.g., less than 6 months of consistent activity), would provide useful information.

Although to date the RPM has not been shown to be espe-cially informative in studies of adoption of exercise, very little research has been conducted to evaluate alternative factors im-pacting the magnitude of the Abstinence Violation Effect and the utility of RPM components in understanding exercise main-tenance. Future exercise research may be informed by studies of alcohol and smoking relapse. Factors proposed for the preven-tion of relapse in addictive behaviors (52) include degree of goal commitment, effort exerted toward goals, length of time main-taining goals, and degree of value associated with progress made to maintain goals. Future research of exercise maintenance using the RPM can also benefit from the integration of findings con-cerning interventions aimed at preventing relapse and enhancing maintenance of behavior change in the obesity literature (53).

The aspects of the RPM that impact exercise maintenance are complex and may differ between men and women as well as

between moderate and vigorous exercisers. We recognize that exercise behavior may differ from other behaviors typically ex-amined via the RPM. Challenges in the evaluation of the RPM are inherent in the model. For example, many of the constructs and processes within the RPM have proven to be dynamic and are best assessed ecologically and in real-time. We have at-tempted to open a door to the closer examination of the RPM in long-term maintenance of physical activity and exercise. Much can be gained from the integration of more sensitive as-sessment methodology (i.e., real-time monitoring), physiologi-cal assessment, and analyses in studies designed to prospec-tively examine the RPM among larger samples of long-time community exercisers.

REFERENCES

(1) Bouchard C, Shephard R, Stephens T: Consensus statement. In Stephens T (eds),Physical Activity, Fitness, and Health: Inter-national Proceedings and Consensus Statement. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1994, 9–76.

(2) U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General(S/N 017–023–00196–5). Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Preven-tion and Health PromoPreven-tion.

(3) Kujala UM, Kapiro J, Sarna S, Koskenvuo M: Relationship of lei-sure-time activity and morality: The Finnish twin cohort.Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998,279:440–444. (4) Paffenbarger RS, Hyde RT, Wing AL, et al.: The association of

changes in physical activity level and other lifestyle characteris-tics with mortality among men.New England Journal of Medi-cine.1993,328:538–545.

(5) U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Healthy People 2010: Physical Activity and Fitness. Rockville, MD: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available from http://www.healthypeople.gov/

(6) Dunn AL, Marcus BH, Kampert JB, et al.: Comparison of life-style and structured interventions to increase physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness: A randomized trial.Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999,281:327–334.

(7) Marcus BH, Dubbert PM, Forsyth LH, et al.: Physical activity behavior change: Issues in adoption and maintenance.Health Psychology.2000,19(Suppl.):32–41.

(8) Dishman RK (ed):Exercise Adherence: Its Impact on Public Health. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1988.

(9) Sallis JF, Hovell MF, Hofstetter CR, et al.: Lifetime history of relapse from exercise.Addictive Behaviors.1990,15:573–579. (10) Simkin LR, Gross AM: Assessment of coping with high-risk

situations for exercise relapse among healthy women.Health Psychology.1994,13:274–277.

(11) Marlatt GA, Gordon JR: Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in Addictive Behavior Change. New York: Guilford Press, 1985.

(12) Marlatt GA, Gordon JR: Determinants of relapse: Implications for the maintenance of behavior change. In Davidson SM (ed), Behavioral Medicine: Changing Health Lifestyles. New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1980, 410–452.

(14) Marlatt GA, George WH: Relapse prevention and the mainte-nance of optimal health. In Shumaker SA, Schron EB, Ockene JK (eds),Handbook of Health Behavior Change.New York: Springer, 1990, 44–63.

(15) Moser AE, Annis HM: The role of coping in relapse crisis out-come: A prospective study of treated alcoholics. Addiction. 1996,91:1101–1113.

(16) Billings AG, Moos RH: The role of coping responses and social resources in attenuating the stress of life events.Journal of Be-havioral Medicine.1981,4:139–157.

(17) Grilo CM, Shiffman S, Wing RR: Relapse crises and coping among dieters.Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1989,57:488–495.

(18) Tamres LK, Janicki D, Helgeson VS: Sex differences in coping be-havior: A meta-analytic review and an examination of relative cop-ing.Personality and Social Psychology Review.2002,6:2–30. (19) Porter LS, Marco CA, Schwartz JE, et al.: Gender differences in

coping: A comparison of trait and momentary assessments. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology.2000,19:480–498. (20) Curry S, Marlatt GA, Gordon JR: Abstinence Violation Effect: Vali-dation of an attributional construct with smoking cessation.Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology.1987,55:145–149. (21) Marcus BH, Bock BC, Pinto BM: Initiation and maintenance of

exercise behavior. In Gochman DS (ed),Handbook of Health Behavior Research II: Provider Determinants.New York: Ple-num, 1997, 335–352.

(22) Marcus BH, Stanton AL: Evaluation of relapse prevention and reinforcement interventions to promote exercise adherence in sedentary females.Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport. 1993,64:447–452.

(23) Martin JE, Dubbert PM, Katell AD, et al.: Behavioral control of exercise in sedentary adults: Studies 1 through 6.Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology.1984,52:795–811. (24) Belisle M, Roskies E, Levesque JM: Improving adherence to

physical activity.Health Psychology.1987,6:159–172. (25) Sallis JF: Progress in behavioral research on physical activity.

Annals of Behavioral Medicine.2001,23:77–78.

(26) Bock BC, Marcus BH, Pinto BM, Forsyth LH: Maintenance of physical activity following an individualized motivationally tailored intervention. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2001, 23:79–87.

(27) Sallis JF, Calfas KJ, Alcaraz JE, Gehrman C, Johnson MF: Po-tential mediators of change in a physical activity promotion course for university students: Project GRAD.Annals of Behav-ioral Medicine,1999,21:149–158.

(28) Dubbert P, Stetson B, Corrigan SA: Predictors of exercise main-tenance in community women. 94th American Psychological Association Annual Meeting. San Francisco, CA: 1991. (29) Stetson BA, Rahn J, Dubbert PM, Wilner BI, Mercury MG:

Pro-spective evaluation of the impact of stress on exercise adherence in community women.Health Psychology.1997,16:515–520. (30) Rohan KJ, Dubbert PM, Houle TT, Stetson BA: Commu-nity-based excercise and psychological well-being: Towards and exercise prescription for mental health. Manuscript submit-ted for publication.

(31) Godin G, Shepard RJ: A simple method to assess exercise be-havior in the community.Canadian Journal of Applied Sports Science.1985,10:141–146.

(32) Borg G: The perception of physical performance. In Shephard RJ (ed),Frontiers of Fitness.Springfield, IL: Thomas, 1971, 280–294.

(33) Borg GA: Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Medi-cine & Science in Sports & Exercise.1982,14:377–381. (34) Noble BJ, Robertson RJ:Perceived Exertion. Champaign, IL:

Human Kinetics, 1998.

(35) Bandura A: Self-efficacy mechanism in physiological activa-tion and health-promoting behavior. In Madden J (ed), Neuro-biology of Learning, Emotion and Affect.New York: Raven, 1991, 229–269.

(36) Blair SN, Kannel WB, Kohl HW, Goodyear N, Wilson PW: Surrogate measures of physical activity and physical fitness. American Journal of Epidemiology.1989,129:1145–1155. (37) Poag-DuCharme KA, Brawley LR: Self-efficacy theory: Use in

the prediction of exercise behavior in the community setting. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology.1993,5:178–194. (38) Shiffman S, Balabanis MH, Paty JA, et al.: Dynamic effects of

self-efficacy on smoking lapse and relapse.Health Psychology. 2000,19:315–323.

(39) DuCharme KA, Brawley LR: Predicting the intentions and be-havior of exercise initiates using two forms of self-efficacy. Journal of Behavioral Medicine.1995,18:479–497.

(40) McAuley E, Bane SM, Mihalko SL: Exercise in middle-aged adults: Self-efficacy and self-presentational outcomes. Preven-tive Medicine.1995,24:319–328.

(41) Gyurcsik NC, Brawley LR, Langhout N: Acute thoughts, exer-cise consistency and coping self-efficacy.Journal of Applied Social Psychology.2002,32:2134–2153.

(42) Bandura A: Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behav-ioral change.Psychological Review.1977,84:191–215. (43) Bandura A:Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A

So-cial Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1986.

(44) Carver CS, Scheirer MF, Weintraub JK: Assessing coping strat-egies: A theoretically based approach.Journal of Personality & Social Psychology.1989,56:267–283.

(45) Lazarus RS: Coping theory and research: Past, present, and fu-ture.Psychosomatic Medicine.1993,55:234–247.

(46) Zeidner M, Endler NS (eds):Handbook of Coping: Theory, Re-search, Applications. New York: Wiley, 1996.

(47) Shiffman S: Coping with temptations to smoke.Journal of Con-sulting & Clinical Psychology.1984,52:261–267.

(48) McAuley E: Efficacy, attributional, and effective responses to exercise participation motivation.Journal of Sports & Exercise Psychology.1991,13:411–427.

(49) Gwaltney CJ, Shiffman S, Norman GJ, et al.: Does smoking ab-stinence self-efficacy vary across situations? Identifying con-text-specificity within the Relapse Situation Efficacy Question-naire. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2001, 69:516–527.

(50) Shiffman S, Hufford M, Hickcox M, et al.: Remember that? A comparison of real-time versus retrospective recall of smoking lapses. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1997, 65:292–300.

(51) Tennen H, Affleck G, Armeli S, Carney MA: A daily process approach to coping: Linking theory, research, and practice. American Psychologist.2000,55:626–636.

(52) Dimeff LA, Marlatt GA: Preventing relapse and maintaining change in addictive behaviors.Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice.1998,5:513–525.