Ian Roper, Paul Higgins and Phil James

Shaping the Bargaining Agenda? The Audit Commission and Public Service Reform in British Local Government

Abstract

This article examines the role of the Audit Commission (AC) in local government collective bargaining. While the AC has no official role in such bargaining, it has a role in monitoring the performance of local government services. In this role the AC

has a clear potential, in the context of the government’s ‘modernisation’ agenda – as manifested in its ‘Best Value’ regime, for influencing both the content of collective agreements, and the process of collective bargaining, where these are seen to conflict with other Best Value objectives – particularly in relation to external competition. The research conducted involved a content analysis of AC inspection reports on human resource services and longitudinal case studies of two local authority union branches’ experiences of Best Value and the role of the AC. The findings from the inspection reports indicate that, while the AC is actually acting to promote activities that could be seen as supportive of union bargaining agendas, notably in relation to equality type issues, they are also supporting service externalisation and thereby acting to limit the scope of their impact. The reports also indicate that, despite there being prescribed ‘best

practice’ for local government employment relations (‘social partnership’ with unions),

Shaping the Bargaining Agenda? The Audit Commission and Public Service Reform in British Local Government

It has been common in analyses of national systems of employment relations to distinguish between the roles and related actions of governments, employers and trade unions. In the case of government, it has also been common to focus on its role of economic regulator, employer, legislator and provider of various advisory and dispute resolution processes or services. Each of these aspects of the governmental role remains relevant. However, at least in the case of Britain, they have come to be supplemented by the actions of government sponsored regulatory bodies whose remit is to oversee the value-for-money and quality of public services, whether these services are provided by public, private or non-for-profit organisations. A number of such bodies have been created over the last two decades and marked differences exist regarding their areas of activity and the precise roles that they play. For example, some owe their existence to a perceived need to monitor and control the actions and performance of privatised enterprises which have the potential to exploit monopolistic market positions to inflate prices.

This article consequently examines the impact of one such body, the Audit Commission (AC), on the bargaining agenda and institutional position of trade unions in British local government by reference to the regulatory role that it plays under the

British government’s modernisation and reform agenda. This examination embodies two levels of analysis: (1) an empirical investigation of AC inspections of personnel functions and (2) case study research which sheds light on union experiences of the AC inspection process.

The remainder of the article proceeds as follows. Initially, some background information is provided on the nature and changing context of employment relations within British local government, including the place that public service reform occupies within this and its impact on collective bargaining processes. The origins of the AC and the way in which its role has evolved are then examined. This examination is,

then, followed by an explanation of the present study’s methodology and a presentation

of its findings. Finally, the last section draws together the key points to emerge from the preceeding analysis and, in doing so, concludes that the activities of the AC are, indeed serving to shape the bargaining agenda of unions in a way that is broadly – though not exclusively - detrimental to the interests of unions and their members in local government.

The changing context of local government employment relations

high: in 2005 the ‘public administration’ category of employment – of which local government employment contributes a significant proportion of the total - recorded an average density of 57.1 per cent, the highest density for all major employment categories in the UK (Grainger, 2006: 21). In addition, unions’ institutional centrality is further demonstrated by the fact that local level management-union relationships take place within a framework of national bargaining arrangements incorporating not only administrative, professional, technical and clerical (APT&C) staff, but also their manual counterparts, police officers and staff, school teachers, and fire service personnel. Under these frameworks, negotiations take place between the Employers’ Organisation for Local Government, the umbrella body representing local government employers, and the relevant recognised unions. The most important of these, in terms of the number of workers covered, is the National Joint Council (NJC) for local government services, which came into being in 1997 as a result of the merger of the two previously separate NJCs for manual and APT&C staff. This merged NJC now constitutes the largest NJC of any kind in the UK (Local Government Pay Commission 2003). On the union side contributions come from those unions most representative of the sector; UNISON, which holds 31 places on the NJC, followed by the GMB (16) and the Transport and General Workers Union (11).

around the professional autonomy of the local government officer, institutionalised through collective bargaining, to a ‘market state’ orientation – based on the imposition of external competition, outsourcing and micro-management solutions to issues of performance; and finally to the adoption of what may be termed a hybridised regime – whereby micro-management and market-based solutions continue to be pursued, but are now being tempered by protections to the baseline terms and conditions determined at the governmental level.

The Model Employer Era

The basis of local government employment relations practice from the end of the second world war up to the 1970s has commonly been seen as having been centred on the notion of the ‘model employer’. Whilst this notion has been legitimately challenged as overly simplistic (Thornley 1995; Thornley, Ironside and Seifert2000), as a heuristic it nevertheless remains useful as a comparator of the changing ethos of what constitutes

‘good’ employment practice in the sector.

Over time, national level management-union relationships came to encompass collective bargaining, as well as joint consultation, though the assumptions of consensus that underpinned this system became increasingly anachronistic as bargaining became more confrontational in the 1970s against the background of local government budgetary constraints (Fairbrother 1996). This rise in adversarialism, in turn, contributed to a break up of the party political ‘post war consensus’ on employment in public services occurred, most notably through the 1979 ‘winter of

discontent’, which was disproportionately located within local government. This break up came to fruition with the coming into power of a Conservative government in 1979

and the imposition of a ‘market state’ approach to public sector employment relations.

The Market State Era

The market state approach towards employment in local government comprehensively rejected the notion of the ‘model employer’ on the neo-classical, Public Choice premise (Niskanen, 1971) that workers, through their unions, will always seek to insulate themselves from the need to adapt their working practices to improve productivity. This was, in turn, seen to be compounded by a style of management – the now, maligned,

‘public administration’ approach (Pollitt 1993) - that neither had the threat nor the incentive of the competitive market to confront such behaviour.

(DSOs) being compelled to compete for existing work with private contractors on the basis that:

…the terms and conditions of employment by contractors of their workers or the composition of, the arrangements for the promotion, transfer or training of or the other opportunities afforded to, their workforces. (HMSO 1988)

Since local government services are essentially labour intensive, competition for local services inevitably became focused upon labour costs (Ganley and Grahl 1987, Cutler and Waine 1998, Escott & Whitfield 1995; Walsh 1995). In addition, the need under CCT to hold budgets at the individual service level provided managements with a direct incentive to devolve personnel decision-making toward the operational level and thus an encouragement to decentralise collective bargaining in line with prescribed HRM best practice of the time (Legge, 2005). As a result, this led to the importance of national terms and conditions declining and a corresponding rise occurring in the importance of local level bargaining (Beaumont, 1992; Gill, 1995) – a rise which created profound difficulties for trade unions whose internal structures were shaped to mirror the national level Whitley ones (Colling, 1995) and raised the issue of whether unions could effectively adapt their organisational structures and activities to support an effective process of joint regulation at this level.

changes which have been acting to undermine union bargaining power within the state sector offers the possibility of creating conditions for establishing a new active and participatory form of unionism, while also noting that the effective exploitation of this possibility represents a major challenge.

The Evolution of a Hybridised Employment System

The employment relations system that has emerged in local government since 1997 can be seen as a hybridised version of the previous market state approach1. This hybrid

approach is in line with New Labour’s broad approach to employment regulation which emphasises individual employment rights over collective ones (Pollert, 2005; Smith and Morton, 2001) and embodies an enthusiasm for market based solutions to public service reform which, although differing in significant ways to that of CCT, retain some of the regime’s key attributes. As a result, while New Labour did support the conclusion in 1997 of a union-friendly, if ‘uniquely complex’, single-status harmonisation agreement (Local Government Pay Commission, 2003: 23), the general direction of its public service reform agenda has contributed to a deterioration in national level union-government relationships.(Waddington, 2003).

When Labour replaced the Conservatives in government in 1997, it proclaimed that CCT would be scrapped in favour of a policy of ‘Best Value’ (BV). However this

did not signal a return to the idealised ‘model employer’ approach because New Labour, informed by ‘third way’ prescriptions of reform (Giddens, 1998), mistrusted

1 The basis of this hybridised conception is concerned specifically with the employment aspects of

public sector professionals, seeing them as representing ‘producer interests’ which were likely to act as a block to the reforms deemed necessary under a more consumerist oriented reform agenda (Driver and Martell, 1998).

The early impression given was that it did not matter how local authorities pursued BV provided that they delivered it in keeping with New Labour principles of avoiding ideological concerns about ownership (DETR, 1997). Unlike CCT, BV consequently promised to open up the range of management tools available to local government managements, albeit within the confines of the need to review the services they provided in accordance with the ‘four Cs’ of BV; a requirement that obliged them

to ‘challenge’ whether a service should continue to be provided, to consult users over

its current and future shape and performance, to ‘compare’ the service’s current performance with that of similar services elsewhere and to subject the service to competition.

The replacement of CCT with BV has consequently not involved a clear rejection of the ‘public choice’ assumptions that informed the former. Thus, not only does ‘competition’ remain but, in addition, the role that it plays within BV provides for forms of partial outsourcing to be utilised that go beyond the ‘binary’ options of either complete in-house or complete externalisation decisions that were provided for within CCT. The BV review process, therefore, represents a continuation of the ‘enabling’ model of the local authority under which, while services are secured by local authorities, they are not necessarily provided by them directly.

line with the spirit, as well as the letter, of what is prescribed. As a result, local

authority compliance with the ‘4Cs’ of BV is the subject of external audit and inspection and the penalties for ‘failing’ an inspection can not only be very severe, but can themselves involve the externalisation of service provision. As a result, service

outsourcing effectively acts as a ‘default’ mechanism in the event that a local authority fails to fully embrace the objectives and methods of BV.

The introduction of BV has therefore increased the number of avenues through which the private sector can be involved in the delivery of public services and the range of situations in which staff can be transferred from public to private sector employment. Indeed BV can be argued to pose a greater threat to workers who wish to remain council employees than was the case under CCT; an argument which receives support from evidence showing that – at the level of ‘partial transfer’ – it has enabled more externalisation than CCT (Roper, James and Higgins 2005) and raises the likelihood that that the regime is leading to the types of negative effects on work intensification and job insecurity previously associated with CCT (Richardson et al, 2005)

and temporary workers and enhancing maternity, childcare and dependency rights2. At the second level, in the face of pressure from the unions, the government has concluded national agreements that enhance the rights of staff transferred from the public sector. This has included measures addressing the so-called ‘two-tier workforce’, and, on projects affected by the Public Finance Initiatives (PFI), the concluding of the so-called

‘Warwick Agreement’ between Labour and the unions prior to the 2005 general

election. The final level of protection has involved sectoral-level actions which have affected national agreements specifically relating to local government. These actions have included the commitments to pursue ‘best practice’ initiatives on equal pay, single status and on a ‘mainstreaming equalities’ agenda (Ruberry, Grimshaw and Figueiro, 2005) – often specifically tied to BV (Local Government Pay Commission 2003; EO 2001)

These contextual developments, when taken together, suggest that while BV, like CCT before it, does embody a continued emphasis on the externalisation of external services, it does so in an environment that serves to place limits on the extent to which the terms and conditions of those employed by external providers can be lower than those set for directly employed local authority staff through local government collective bargaining machinery. It is for this reason that the issue of how the actions of the regulatory body responsible for overseeing the operation of the BV regime impact on the collective bargaining agenda of local government trade unions seems to be one that merits an investigation of the type undertaken below. For, a clear potential exists for these actions to either support or undermine (a) the content of

2 It should be noted that most of these changes have been prompted by the need to transpose the

bargaining agendas that the unions wish to pursue and (b) the role that they may play in pursuance of these – or other – bargaining agendas.

The Audit Commission’s expanding remit from CCT to BV

One of the paradoxes of the Public Choice agenda for reform is that markets for public

services do not ‘make’ themselves; they have to be made artificially by the state and then somehow regulated. In local government the operationalisation of CCT, and later BV, has been monitored by the AC, set up in 1983 to ensure a transparent tendering

process and through this the application of ‘market discipline’ to staff and their unions

(Vincent-Jones and Harries 1996). This responsibility meant that the AC was implicitly drawn into the contested terrain of local government industrial relations, though it had also been a champion of some of the management reforms implicated by CCT via the

stress it placed on the importance of the ‘make or buy’ decision (Audit Commission,

1987) and the ‘best practice’ guidance it published with respect to the ‘ideal’ separation

of client and contractor responsibilities (Audit Commission, 1995a). More generally, the AC has been at the forefront of promoting value for money (VFM) in local

government services as defined primarily in terms of the ‘3Es’ of economy, efficiency

and effectiveness - three concerns which complimented the competition/management aspirations of CCT.

Since 1983 the remit of the AC has expanded in scale and scope. In terms of scale, its remit was expanded in the early 1990s to cover the joint inspection of social services. However, with the introduction of BV, the scope the AC’s role has expanded from being an assessor of (cost) efficiency into one of being an arbiter of output

responsibility for BV inspection (Local Government Act, 1999, Section 10), which dwarfs the policing functions previously endowed upon it with respect to local

authorities’ adherence to CCT rules and regulations (Colling, 1999) by reaching judgements concerning the ‘current’ and ‘likely future’ performance of BV reviewed services (Audit Commission, 2000).

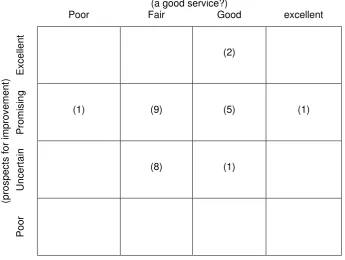

Current performance for these inspection purposes was then assessed as ‘poor’,

‘fair’, ‘good’ or ‘excellent’ and likely future performance as ‘poor’, ‘uncertain’,

‘promising’ and ‘excellent’. Where an unfavourable inspection judgement was made, it

was open to the Secretary of State to impose one of a number of sanctions. Under section 15 of the Local Government Act 1999, these include, the provision of external management help, the requirement that services be put out to competition, the seizure

of the authority’s ability to provide services directly and the transference of service responsibility to a third party. While the ramifications of a particular inspection judgement could, therefore, be quite severe, the BV inspectorate was keen to stress that it was not merely operating a penal system. Instead, as part of the BV inspection visit, each authority received recommendations that indicated how it might improve its future service performance. Thus, as the AC (1999: 17) maintained:

‘Councils might find it unhelpful if the inspectorate simply questioned the quality of a review, without indicating how it expected a council to make improvements’.

Since the introduction of BV in 1999, Labour’s reform of local government has moved on at a rapid pace and in 2002 the tangential policy of comprehensive performance assessment (CPA) was introduced. This more recent policy initiative involves auditors

and inspectors assessing local authorities’ entire performance rather than, as in BV, the

In pursuit of service quality, the AC’s work can clearly be seen to have the potential to impact on the bargaining agendas of unions. A clear demonstration of this is the way in which its work formed an important backcloth to the 2002/03 dispute in the British fire service and its aftermath. Thus, while assessments of this dispute – or its antecedents – do not identify the AC as the key protagonist, the AC’s initial recommendations for reform (Audit Commission 1995b) have been identified as an important catalyst to the dispute and its subsequent policing of ‘modernisation’ following the dispute’s resolution, been seen as playing an role in shaping the ongoing contested situation in the service (Burchill, 2004; Fitzgerald, 2005).

Likewise, the role that AC inspectors are playing in terms of shaping local government employment relations, furthermore, receives support from the content of a briefing document that the AC has produced on managing people in local government (Audit Commission, 2003). Thus, while this provides guidance on six factors which are seen as critical to successful people management – empowering leadership, people management strategies, managing performance, capacity building, workforce diversity and recruitment and retention, it is remarkably silent as to the role of unions and union-management relations, beyond the making of a few passing references to these issues in two of the illustrative case studies provided in the document, and hence does little to encourage local government employers to work closely with unions.

justified by the need to demonstrate ‘competitiveness’. The second dimension is through influencing the process of collective bargaining. Here the influence would be by encouraging forms of consultation and communication outside established collective bargaining mechanisms or by discouraging union-management dialogue.

More generally, on the basis of the foregoing analysis, it is possible to identify three different ways in which the impact of the AC on the process and outcome of collective bargaining could be generated:

By encouraging the externalisation of services and in this way undermining the degree to which service provision falls within the scope of national and in-house negotiations and, via the competitive processes involved, limiting the ability of

unions to protect and enhance workers’ terms and conditions of employment;

By prompting employers to seek to introduce new human resource policies and practices in respect of staff and thereby shaping the focus and nature of in-house negotiations in a way conduicive to, or at odds, with union bargaining; and

By supporting, or undermining, the more general (institutional) position of unions and thereby role that they play in the regulation of in-house employment relations.

Methodology

these analyses enable a rounded picture to be gained of the extent to which the AC’s activities support, or contradict, union bargaining objectives and priorities, and thereby strengthen and weaken their role in shaping local government employment relations.

The first strand of analysis involved the examination of all 27 BV inspection reports relating to local authority human resource/personnel departments available as of February 2005. The purpose of this examination was two-fold. First, to identify (a)

those aspects of the services which were deemed ‘praiseworthy’, (b) those aspects that were deemed problematic and in need of improvement, and (c) those aspects in respect of which the inspectors were moved to make recommendations. Secondly, within each of these categories, a frequency analysis of the various issues so identified was undertaken so as to highlight those which could have positive or negative implications for the content (and to a lesser extent process) of union bargaining agendas.

The second strand comprised the use of data drawn from longitudinal case studies conducted in two local authorities between 1995 and 2004 which were, more broadly, focussed on local level experiences of the transition from CCT to BV. The first case study was a large English northern metropolitan authority; the second was an English southern urban authority – with a particular focus on waste services. The main method of enquiry in both these studies was semi-structured interviews, but policy documentation, secondary sources and – in one case – a questionnaire survey was also used at the early stages. Initial interviews in the northern authority (conducted between 1995 and 1997) were with senior corporate and service managers (2), line managers (2), the UNISON branch secretary and the union workplace representatives (10). In the southern authority (conducted between 1999 and 2002) twenty four initial interviews were conducted including senior managers (4) line managers (8) contractors (3), the

interviews, conducted in 2004, involved re-interviewing the union branch secretaries from each authority and, in the northern authority, further interviews with eight workplace union representatives.

In the northern authority, an important part of the data collected at the authority-wide level related to the authority’s performance in relation to the retention of all services in-house under CCT, the challenge that BV, and associated changes in Council leadership policy, posed for such retention, the way in which the main trade union and Council management sought to address this challenge through the development of a

joint agreement on ‘service procurement’ and the manner in which the development of

this agreement was shaped by both the BV regulatory regime and the actual, and anticipated, attitude of AC inspectors towards it.

As regards the southern authority, a central focus of concern within it was the examination of the experiences of its refuse collection service under both CCT and BV. As part of this examination, the degree of trade union involvement in the developments which occurred under BV was explored and insights gained into how BV inspectors viewed this involvement.

recognition is ubiquitous. Meanwhile, the second strand permits valuable qualitative observations to be made concerning the weight that the AC attaches to the issue of union involvement during the course of undertaking BV reviews of local authority services more generally.

Evidence from human resource inspection reports

To set the scene for the analysis of the inspection reports on human resource/personnel departments, the overall judgements on current performance and prospects for future improvement are initially provided. In the case of current performance, this examination, as Figure 1 shows, reveals that the majority (17) of the departments were judged as being ‘fair’, with a minority (8) being viewed as ‘good’ and only 2 being

judged on the extremities of being either ‘poor’ or ‘excellent’. Meanwhile, in terms of prospects for future improvement, the majority (16) of the services were judged as

having ‘promising’ chances, with the prospects of most of the remainder (9) being seen

as ‘uncertain’.

(insert figure 1 about here)

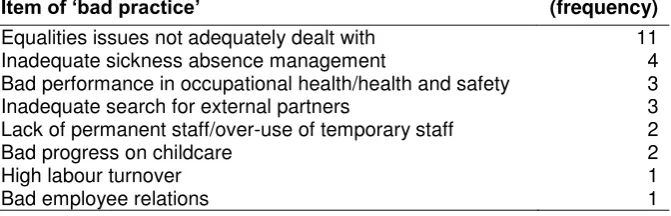

With regard to the aspects of human resource/personnel performance that BV inspectors viewed as praiseworthy and problematic - and on which they felt moved to make recommendations - these are detailed in Tables 1-3 below.

From Table 1, it can be seen that 14 different ‘praiseworthy’ issues of relevance were identified in the inspection reports; although only four of these were mentioned more than twice. Taken together, these issues would seem to have both positive and negative implications for union bargaining agendas. Thus, on the positive side, they encompass inspector endorsement of those departments which were seen to have done well in relation to a number of aspects of performance which can be assumed to be compatible with union bargaining objectives – the promotion of equality issues, progression towards single status terms and conditions, regular consultation, the provision of good facilities for disabled workers and good standards of health and safety. On the other hand, the reports also embody inspector endorsement of a number of features of departmental performance, use of externalisation, moves towards performance related pay and workforce reductions, which unions would almost certainly view as problematic and would not, of their own volition, raise for discussion. In addition, while one of the more commonly mentioned areas of inspector praise, the improvement of sickness absence management could potentially be an area of joint management-union interest, it is strongly hinted in the language of the reports that the inspectors were more concerned with reducing ‘absence’ and less with the component of this issue that unions would be more likely to be positively interested in, namely

‘sickness’ reduction (TUC 2005).

union interests. At the same time, however, it needs to be acknowledged that whilst a high number of issues being praised may be of common interest to management and unions, the process of union engagement on them may not be. In this respect, a striking feature of the reports is that no mention is made – remembering that this is the inspection of the personnel function in a sector where union recognition in the sector is universal and membership density is high – of the importance of management adopting a positive and supportive approach towards union involvement.

(insert table 2 about here)

When attention is turned to the rather fewer issues that gave rise to explicit inspector criticisms of performance, a similar pattern emerges. Thus, only one of the items detailed in Table 2 above, namely the making of inadequate efforts to identify external partners, would seem clearly to relate to a matter that would be likely to conflict with union bargaining priorities, while the majority of those raised would seem compatible with them – with the partial exception, given the discussion above, of that

of ‘sickness’

(insert table 3 about here)

one-way communications, and references to union engagement are, again, notable by their absence.

Case study 1: Northern Metropolitan Authority

The relevant findings of this case study are detailed through an exploration of three

main issues. The first of these is the authority’s experiences of in-house service retention under CCT and in the early stages of BV. The second is the factors that prompted union and management in the authority to pursue the conclusion of a joint agreement on service procurement and the nature of the agreement so concluded. The third is the way in which the contents of this agreement were shaped by the requirements of BV and the attitudes, both actual and anticipated, of AC inspectors.

In-house service retention under CCT and BV

Under CCT, the UNISON branch at Northern Metropolitan Authority proactively sought to retain services in-house, in collaboration with management and the political leadership, which was Labour dominated. To this end, it therefore accommodated a variety of management initiatives aimed at securing successful in-house bids – an approach that proved a complete success..

… if you go though a rigorous review and you’re actually willing to do the ‘challenge’ in the way we’re meant to, if its not around the philosophy of

externalising whatever, it can be a positive process: actually involving the workforce in that type of review and how do we deliver service improvement. There has been some good practice developed here. (2004)

A new chief executive, however, was appointed who took the council’s political

leadership with him on a ‘modernisation’ agenda replete with references to

commercialisation and external partnerships. As part of this new policy agenda, a proposal was made to outsource the Council’s information technology support (ITS). This was met with met with fierce union opposition – backed by the strong feelings of staff working in the affected area – which, ultimately, resulted in the union mobilising members throughout the council to undertake strike action. In the face of this action,

the external ‘partner’ pulled out of the deal.

Partnership – but not as we know it?

Not long after these events, the chief executive left the council and UNISON decided that it needed to deal explicitly with the issue of procurement as a strategic issue and to do so through the securing of an agreement with management on the subject. In

seeking such an agreement, the union’s approach was, in many ways, couched in the language of union-management ‘partnership’ favoured by the government. However, this language was utilised against the backcloth of the union possessing a clear and credible mobilising capacity and retaining a principled opposition to externalisation.

[...ITS] became the key focus […] We said to them ‘look, we can either have this battle every time or we can actually look at a strategy that actually takes out the conflict. We may not like it – its [government] policy – [but] there’s probably a strategy we can develop that can allow us to actually avoid this. (UNISON Branch Secretary 2004)

The resulting procurement agreement, which was signed in 2004 and amounted to 78 pages, promoted ‘fair employment practices’ and secured union rights to be involved in all stages of any potential outsourcing scenario – even extending into previously unregulated areas of employing agency staff and contractors.

The clear agreement is, we will develop an in-house comparator as well as look at alternative models. … My view always will be that if we get that process right then we will win hands-down every time. (UNISON Branch Secretary 2004)

The influence of external regulation on the procurement agreement

UNISON was conscious, from the early stages of BV, of the potential constraining influences of the AC on its own agenda to retain in-house service provision. This became more apparent as the results of AC inspection reports began to come through. For example the Corporate Assessment of the Council in 2002 summarised that the

Council’s approach ‘…makes excessive allowance for even a demonstrably uncompetitive in-house service to benefit from a protracted opportunity to turn itself

around before alternative options are considered’. It was for this reason that the wording of the agreement was carefully vetted.

The procurement strategy is written in Audit Commission language. We took the procurement policy and re-wrote it – literally – in their language. What we said

was ‘what are the key principles we want at every stage’ …What we’re trying to

create was a level playing field. [With] the political backdrop that says ‘yes we

The dangers of failing an AC inspection are serious, as has been noted above. As a result the council was nervous about attracting criticism from the AC. While the 2005 CPA report praised the council for the adoption of the procurement strategy- interestingly because it was claimed to have enabled framework agreements with external contractors - this assessment was preceded by criticism, in a 2002 report, of

the council’s unwillingness to ‘use competition as a way of improving core council

services’. This criticism was, in turn, seen as stemming from political weakness. UNISON’s branch secretary was in no doubt as to the direction and influence of these criticisms:

I went to a seminar - a briefing - that was given by two senior inspectors from the Audit Commission. And it was incredible. They launched into [the council] because the Labour group had passed the motion – as part of the battle on ITRS, remember - they passed a motion committing themselves to in-house

service provision. And you had inspectors standing up there saying ‘this is absolutely unacceptable’. I mean, I went ‘who are you? What is going on; you

have no right to be doing this!’. … And that made the management ultra cautious even though the procurement policy that went away, [was checked] with the Audit Commission, the CPA people … [T] hey are so frightened of the Audit Commission and the inspection regime. And that does influence a lot of the thinking. (2004)

Case study 2: Southern Unitary Authority

The second case study covered developments at a waste services department of a south-coast unitary authority. In a similar format to the presentation of the findings from the first case study, attention is focussed on the experiences under CCT, the early experiences of BV and the attitudes, both actual and anticipated, of AC inspectors.

The previous experience of CCT had been turbulent. The Labour administration had managed to retain in-house provision of refuse collection, but at a significantly under-bid price and with no consultation with the unions – resulting in significant industrial unrest. When quality problems arose with the service it was outsourced, with Department of the Environment approval, to an alternative single service provider (along with some other activities). Given the alternatives the union agreed, despite some misgivings amongst its own membership, to the management’s plans, but with certain ‘TUPE-plus’ guarantees for the workforce which extended the protections to the terms and conditions of transferred staff under the Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) Regulation 1981 to the retention of membership of the local government pension scheme and gave assurances of full union participation in the drafting of the new employment contracts. The new external provider, however, began to face problems in delivering the service for the price agreed and further alternatives were sought.

Developments under BV

sufficiently well resourced to attain the enhanced quality service claims made for it. As the branch secretary explained:

‘The council conducted the BV tendering exercise on the basis of ‘let the

companies’ do the undercutting, let them do the subsidy and leave it up to the

unions to manage the staff problems’. (2004)

As the contract commenced, the new management attempted to deal with the workforce by direct ‘open briefings’ and by bypassing the union. The most notable example of this was when it, in the face of strong reservations, replaced the authority’s longstanding ‘beat system’ of working (where teams of workers were allocated specific area of the city that they continually worked) with a ‘zone-based system’ (where the entire workforce operated in one large area of the city then moved on to another area) in a bid to improve productivity and ‘to make a reality of the bid’. The result was the alienation of the workforce who quickly demonstrated that management could not operate the service without the good will and tacit skills of front line staff. As a union official further explained the workforce felt particularly aggrieved at management’s attempt to bypass them:

‘On average when you do a refuse re-route the refuse crews will, within a month find the quickest way of getting around it, they are very good at finding the quickest way to finish their work. If changes are imposed that leave little in the way of discretion, then you can expect a drop in productivity.’ (2004)

external contractors would only operate the contract in return for at least a two-fold increase in cost, the Authority decided that the only realistic option was to return the service in-house. It was at this point that a newly established city cleansing team was provided with the opportunity by the council to undertake a fresh BV review entitled

‘waste management services’. In the formal documentation, the review was reported as providing the ‘opportunity to work in partnership with the workforce’ whilst ‘ensuring that the refuse collection and street cleansing is provided at the lowest possible cost for

much improved quality’

The BV inspection

Following two years of unsatisfactory service performance from its external contractor and having only regained direct control of the integrated refuse collection and street cleansing service for a period of six months, the council was subjected to an inspection of ‘Waste Management Services.’ The AC’s view of the authority’s tumultuous experience of BV was broad support for what the Council had being trying to do with its outsourcing policy. Indeed, the inspection report for this service – then the second most expensive in the country and with what might otherwise be seen as an unsuccessful experience of outsourcing – was of a ‘fair’ service with ‘promising’ prospects for improvement. Moreover, despite the torrid history of the former contract, the only mention of the former contractor in the resulting BV inspection report was limited to the following short statement:

‘The service is delivered by the Council’s own staff following the termination of

The AC acknowledged that there had been an improvement in staff morale and an improved relationship with the trade union since the service had returned in-house. However, no recommendations were made with regard to the preservation or furthering of this improvement. In fact, the overall impression given in the report was that the AC was keen to encourage sporadic employee involvement but less concerned with on-going employee participation - to the extent that it even encouraged management efforts to unilaterally revise working methods and practices. Finally, further notable

amongst one of the AC’s concluding remarks was that over time ‘the council would need to continue to assess alternative options for service delivery to remain

competitive’. For this recommendation, therefore, implied the reintroduction of competition at some later stage, with the attendant risk involved of further alienating employees who had, since the introduction of CCT some fifteen years previously, continuously experienced the ills of being passed from one external contractor to another.

This continued commitment of the AC inspectors to the role of competition and externalisation can consequently be seen to echo the findings obtained from the first case study reported above. It can also be seen to accord with the results of the earlier examination of inspection reports indicating that, when reviewing human resource/personnel departments, inspectors attached much important to this issue.

Conclusions

article has explored how the work of one such body, the AC, impacts on the bargaining agenda and role of trade unions in British local government. It has done so by drawing on quantitative and qualitative findings derived from the examination of inspection reports relating to local authority human resource/personnel departments and from two longitudinal case studies that shed light on union experiences of the inspection process associated with BV.

The analysis of the inspection reports reveals that AC inspectors, through a combination of praise, criticism and recommendation, provided a clear indication to local authorities of the human resource/personnel management issues – the potential content of collective bargaining agreements - which they deem to be of central importance. On strictly numerical terms inspectors more commonly endorse and praise aspects of human resource management that are compatible with, rather than in conflict with, likely union bargaining objectives. At the same time, they continue to attach great importance to departments demonstrating that they have adequately explored the potential which existed to externalise services, or at least parts of them; an attachment that could serve to the challenge local union branch interests and to undermine some of these ‘positive’ recommendations. Thus, while the TUPE regulations would provide some protection for continued union recognition of transferred staff, externalisation would lead to the direct removal of members from the local (council) branch, as well as potentially leading to the transferred staff no longer being covered by NJC agreements. In addition, and paradoxically, such staff could no longer relay on the AC to comment on any HR issues affecting them, including progress on single status, work-life balance or other equality-related issues.

management-union relationships, despite the fact that the human resource/personnel departments being examined would, without exception, have been operating in environments of union recognition and relatively high degrees of union membership. It would, therefore, seem on the basis of them that the AC is, in general, little interested in the nature of the relationships that an authority has with in-house unions.

This last conclusion, moreover, received reinforcement from the reported findings of the two case studies. Thus, notwithstanding that both related to situations in which union-based industrial action had taken place and there had been a marked absence of union involvement in decisions as to the nature of future service provision and the reform of working practices, in neither case did inspectors voice criticisms of management for this lack of involvement, nor did it comment on what could be done to avoid such action in the future. Indeed, in the Northern authority case, there were indications of AC officials being suspicious of an attempt by the authority and the main trade union to conclude a joint agreement on future policy towards the procurement of services because of fears that it would act to limit the potential for service externalisation.

endanger the establishment and maintenance of harmonious collective relationships; a suggestion which therefore raises the distinct possibility that the work of government agencies such as the AC may be serving to limit the potential which exists for unions to renew themselves through workplace based activity in the way suggested by Fairbrother and others.

The validity of these findings regarding the role that AC inspectors are playing in terms of shaping local government employment relations, furthermore, receives support from the previously mentioned guidance that the AC has produced on managing people in local government (Audit Commission, 2003). For, as already noted, a striking feature of this is that it says virtually nothing about either the role of unions or the conduct of management-worker relations, despite central government and

employer organisation official promotion of ‘workplace partnership’ with unions in the sector.

As to the reasons why the AC is, philosophically, acting to encourage such an approach, no definitive answer can be given on the basis of the findings reported here. However, the authors would refer back to underlying assumptions that underpinned the establishment of the AC in the first place - Public Choice theory – which is liable to make the AC institutionally mistrustful of (1) monopoly and (2) union management collusion. In the current climate it would be reasonable to conclude that, for the

management of local government employment relations, the AC’s remit for monitoring

service improvement manifests itself through exclusively managerially defined objectives; or through ideological definitions as to what constitutes the public good. Considering that employees are, using the terminology of service quality management,

employee representatives is in marked contrast to the AC’s assessment of other services

where service user engagement is an important focus for its scrutiny.

Of course, what may be speculated as influencing the institutional preferences of the AC does not necessarily explain the actions and behaviours of individual AC inspectors. Consequently, it almost goes without saying that the way in which AC inspectors carry out their work is one that merits further detailed research attention. Acknowledgements

Grateful acknowledgements made to two anonymous referees and the editor for their advice on an earlier version of this article.

Authors Ian Roper

Human Resource Management Group Middlesex University Business School London

Paul Higgins

Human Resource Management Group Middlesex University Business School London

Phil James

Professor of Employment Relations Oxford Brookes University

References

Andrews, R. (2004) ‘Analysing Deprivation and Local Authority Performance: The implications for CPA’, Public Money and Management, 24/1: 19-26.

Audit Commission. (1987) Competitiveness and Contracting Out of Local Authorities' Services. London: HMSO.

Audit Commission. (1995a) Making Markets: A Review of the Audits of the Client Role for Contracted Services. London: HMSO.

Audit Commission. (1995b) In the Line of Fire: Value for Money in the Fire Service. London: HMSO.

Audit Commission. (2000) Seeing is Believing: How the Audit Commission will Carry Out Best Value Inspections in England. London: Audit Commission

Audit Commission. (2003). Managing People – Learning from Comprehensive Performance Assessment: Briefing 3. London: Audit Commission.

Bach, S. (1999) ‘Europe: Changing Public Service Employment relations’. In S. Bach,

L. Bordogna, L. Della Rocca and D Winchester (eds) Public Service Employment Relations in Europe. Transformation, Modernisation or Inertia?, 1-21. London: Routledge

Beaumont, P. (1992) Public Sector Industrial Relations. London, Routledge Colling, T. (1995) ‘Renewal or Rigor Mortis? Union Responses to Contracting in

Local Government’ Industrial Relations Journal, 26/2:134-145

Colling, T. (1999) ‘Tendering and Outsourcing - Working in the Contract State’. In Corby, S. and White, G. (eds) Employee Relations in the Public Services - Themes and Issues. London: Routledge.

Cope, S. and Goodship, J. (2002) ‘The Audit Commission and Public Services: Delivering for Whom?’ Public Money and Management, October-December: 33-40

Cutler, T. and Waine, B. (1998) Managing the Welfare State. Text and Sourcebook. Oxford: Berg.

Deacon, A. (2002) Perspective on Welfare, Buckingham, Open University Press DETR (1997) Replacing CCT with a Duty of Best Value: Next Steps. London:

Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions.

Driver, S. and Martell, L. (1998) New Labour. Politics After Thatcherism, Cambridge, Polity Press

EO (2001) Approaches to Best Value Series: No Quality Without Equality. London: Employers Organisation for Local Government

Escott, K. and Whitfield, D. (1995) The Gender Impact of CCT in Local Government. Manchester: Equal Opportunities Commission

Fairbrother, P. (1996) ‘Workplace Trade Unionism in the State Sector’ In Ackers, P., Smith, C. and Smith, P. (eds): The New Workplace and Trade Unionism. London: Routledge.

Fairbrother, P. (2000) Trade Unions at the Crossroads. London: Mansell

Fosh, P. (1993) ‘Membership Participation in Workplace Unionism: the Possibility of Union Renewal’, British Journal of Industrial Relations, 34/4:577-592

Ganley, J. and Grahl, J. (1988) ‘Competition for Efficiency in Refuse Collection: a Critical Comment’, Fiscal Studies 9/1: 80-5.

Giddens, A. (1998) The Third Way: The Renewal of Social Democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Gill, W. (1994) ‘Decentralisation and Devolution in Local Government: Pressures and

Obstacles’, Industrial Relations Journal, 25/3: 210-221

Grainger, H. (2006) Trade Union Membership 2005, London, Department of Trade and Industry

HMSO (1988) Local Government Act. London: HMSO

Legge, K. (2005) Human Resource Management. Rhetorics and Realities. Anniversary Edition. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Local Government Pay Commission (2003) Report of the Local Government Pay Commission

Miller, C. (1996) Public Service Trade Unionism and Radical Politics. Aldershot: Dartmouth

Newman, J. (2001) Modernising Governance. New Labour, Policy and Society, London, Sage

Niskanen, W. (1971) Bureaucracy and Representative Government. Chicago: Aldine-Atherton

Pollert, A. (2005) ‘The Unorganised Worker: the Decline in Collectivism and New

Hurdles to Individual Employment Rights’ Industrial law Journal, 34/3: 217-238 Pollitt, C. (1993) Managerialism and the Public Services. The Anglo-American

Experience, 2nd Edition, Oxford: Blackwell

Richardson, M., Tailby, S., Danford, A., Stewart, P. and Upchurch, M. (2005) ‘Best

Value and Workplace partnership in Local Government’, personnel Review, 34/6:

713-728

Roper, I., James, P. and Higgins, P. (2005) ‘Workplace Partnership and Public Service

Provision: the Case of the Best Value Performance regime in British Local

Government’, Work, Employment and Society, 19/3: 639-649

Ruberry, J., Grimshaw, D. and Figueiredo, H. (2005) ‘How to Close the Gender Pay Gap in Europe: Towards the Gender Mainstreaming of Pay Policy’, Industrial Relations Journal, 36/3:184-213

Smith, P. and Morton, G. (2001) ‘New Labour’s Reform of Britain’s Employment law:

Terry, M. (2000) Introduction: UNISON and Public Service Trade Unionism. In Terry, M (ed) Redefining Public Sector Unionism: UNISON and the Future of Trade Unions. London: Routledge

Thomson, A. and Beaumont, P. (1978) Public Sector Bargaining : a Study of Relative Gain . Farnborough: Saxon House

Thornley C (1995) The ‘Model Employer’ Myth: the need for Theoretical Renewal in Public Sector Industrial Relations Paper presented to 13th Annual Labour Process Conference 5-7 April 1995

Thornley, C., Ironside, M. and Seifert, R. (2000) ‘UNISON and Changes in Collective

Bargaining in Health and Local Government’. In Terry, M (ed) Redefining Public Sector Unionism: UNISON and the Future of Trade Unions. London: Routledge

TUC (2005) Sicknote Britain? Countering an Urban Legend. London, Trades Union Congress

Waddington, J. (2003) ‘Annual Review Article: Heightening Tension in Relations

Between Trade Unions and the Labour Government in 2002’ British Journal of Industrial Relations. 41/2:335-358

Figures and Tables

Figure 1: AC Inspection Results for Human Resource Functions

(a good service?)

Table 1: Attributes mentioned as praiseworthy in inspection reports

Praiseworthy feature (frequency)

Use of, or consideration of, an external partner 6

Promotion of equality issues 5 Success in reducing the size of the workforce 2

Partnership across the public sector 2

Good employee relations – few disputes 2

Good employee relations advice 2

Creating jobs 1

Good ‘family friendly’ working practices 1

Table 2: Attributes mentioned as bad practice in inspection reports

Item of ‘bad practice’ (frequency)

Equalities issues not adequately dealt with 11 Inadequate sickness absence management 4 Bad performance in occupational health/health and safety 3 Inadequate search for external partners 3 Lack of permanent staff/over-use of temporary staff 2

Bad progress on childcare 2

High labour turnover 1

Bad employee relations 1

Table 3: Recommendations from inspection reports

Recommendations (frequency)

Improve equal opportunities/diversity performance 10 Consider external sources/review procurement policy 5 Improve (one way) communications with staff 3

Improve sickness absence management 3

Improve equity of provision across all staff 3

Improve health and safety management 2

Introduce a capability procedure 2

Increase devolution of HR issues to line managers 2

Make progress on single status 2

Improve opportunities for flexible (family friendly) working 1

Set targets for employee relations 1

Review staff turnover 1