A STUDY ON EQUIVALENCE AND NON-EQUIVALENCE

IN ENGLISH-INDONESIAN TRANSLATION

A Thesis Presented to

The Graduate Program in English Language Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of

Magister Humaniora (M.Hum)

in

English Language Studies

By

Anselmus Sudirman Student Number: 046332001

THE GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE STUDIES SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY

YOGYAKARTA 2007

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE………..… i

APPROVAL PAGE ………..…. ii

BOARDER OF EXAMINERS……… ... iii

STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY……… iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………..….. v

LIST OF TABLES ..………..……. vi

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ………... vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS………..………. viii

ABSTRACT ……….. xi

ABSTRAK………. xii

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION ………. 1

1.1 Background……….……… 1

1.2 Problem Identification……..……….. 9

1.3 Problem Limitation………..………….……….. 11

1.4 Problem Statement………..……… 12

1.5 Research Goal……….…... 13

1.6 Research Benefit ………..……….. 14

CHAPTER II LITERATURE REVIEW ………... 16

2.1 Theoretical Review ……….……….……... 16

2.1.1 Translation..………... 17

2.1.2 Equivalence ……….…. 24

2.1.3 Non-equivalence………... 32

2.1.4 Translation Strategies ………..………….... 33

2.1.5 Translation Processes ……….. 36

2.1.6 Translation Norms…..……….. 39

2.1.6.1 Gideon Toury’s Norms in Translation .… 39

2.1.6.2 Gideon Toury’s Laws of Translation…... 40

2.1.6.3 Chesterman’s Norms ……….... 40

2.1.7 The Quality Translation ……… 41

2.1.8 Kinds of Translations……… 42

2.1.9 Translation Studies ………... 45

2.2 Theoretical Framework……….……… 45

CHAPTER 111 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY ………. 51

3.1 Method……….……… 51

3.2 Setting………..……… 52

3.2.1 Setting of Place …..……….….. 52

3.2.2 Setting of Time… .……… 52

3.3 Data Classification.. …………. ………. ……… 52 3.3.1 Types of Data……..……….……….. 52

3.3.2 Data Coding………... 53

3.3.3 Nature of Data………. ………. 55

3.4 Variable Identification .. ……… 56

3.5 Data Collection Procedures ……… 56

3.6 Data Collection Instruments……… 57

3.7 Respondents ……….. 57

3.8 Data Analysis Procedures………... 58

CHAPTER 1V ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION ………..……. 71

4.1 Equivalence and Non-equivalence ……… 71

4.1.1 Lexical Equivalence and Non-equivalence….. 72

4.1.2 Lexical Categories ……….………..… 81

4.1.2.1 Nouns……… 82

4.1.2.2 Verbs… . ..……… 90

4.1.2.3 Adjectives ……….... 94 4.1.2.4 Adverbs……..……….. 100

4.1.3 Grammatical Equivalence and Non-equivalence ……….. 106

4.1.3.1 Number………. 106

4.1.3.2 Person and Gender……… 110

4.1.3.3 Tense and Aspect ………. 114

4.1.3.3.1 Past Tense ……….… 114

4.1.3.3.2 Non Past Tense ………. 116

4.1.3.3.3 Voice ………. 118

4.1.4 Semantic Equivalence ……… 120

4.1.4.1 Semantic Non-equivalence……. …….. 126

4.1.4.2 Semantic Variability………... 132

4.2 Translation Strategies ………... 136

CHAPTER V GRAND CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS ………... 144

5.1 Conclusion………... 144

5.2 Implications ………..……….. 148

5.2.1 Translation Equivalence…….……… 148

5.2.2 Translation Non-equivalence ……….…... 148

5.2.3 Translation Strategies ……… 149

5.3 Recommendation ………..….. 150

5.3.1 Equivalence and Non-equivalence ……….. 150

5.3.2 Translation Teaching………. 150

5.3.3 Translation Education……… 151

BIBLIOGRAPHY ……… . .. 152

APPENDICES ……….. 157

Appendix 1: The Source Language Text………..………. 158

Appendix 2: Coded Source Language Text………..… 159

Appendix 3: Translated Texts……….……….. 160

Appendix 4: Summary of Coded Target Language Texts……… 165

Appendix 5: Interview Blueprint………..… 167

Appendix 6: Interview Narratives ……… 168

List of Tables

Page

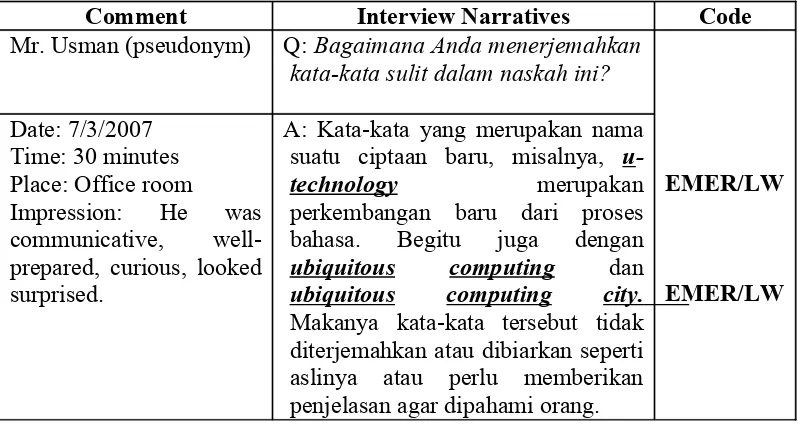

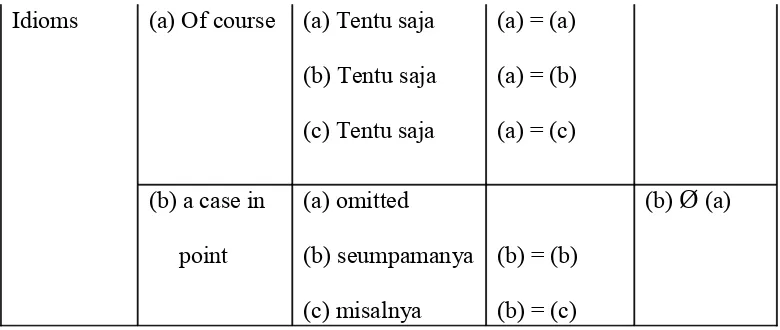

Table 3.1 The Example of Interview Narratives ……….. 54

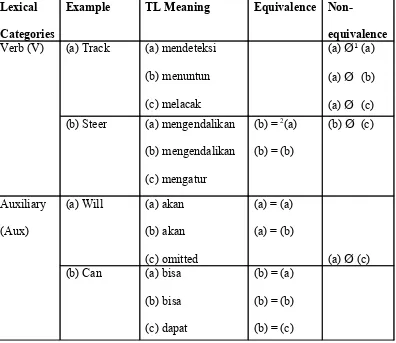

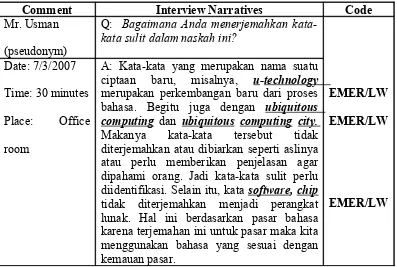

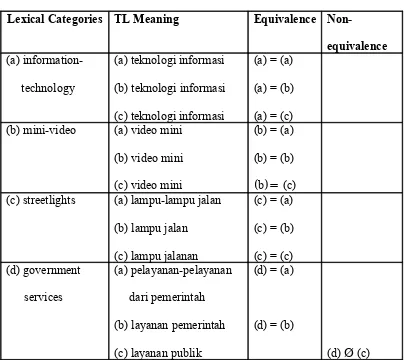

Table 3.2 The Example of Lexical Equivalence and Non-equivalence …….. 60

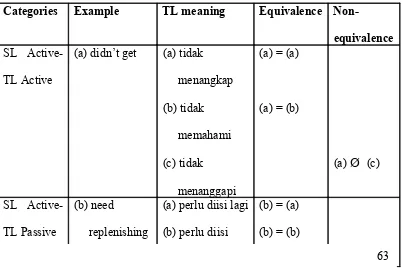

Table 3.3 The Example of Voice ……… ..……….. 63

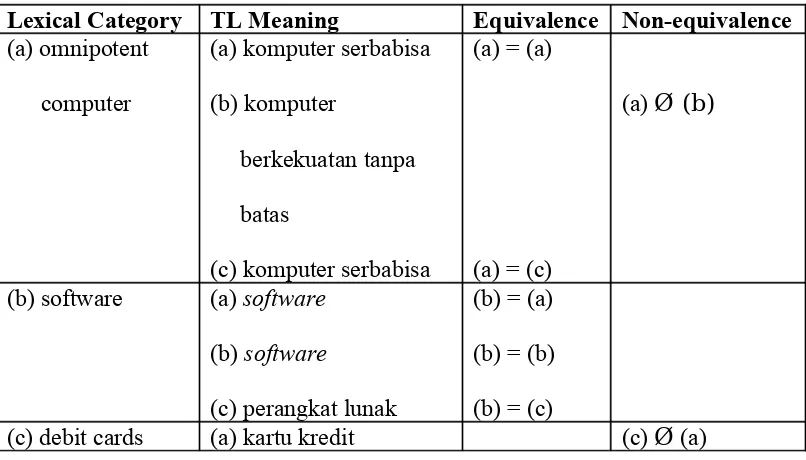

Table 3.4 The Analysis of Figurative Meaning ……….. 66

Table 3.5 The Example of Strategy Codes …..……… 66

Table 3.6 The Example of Interview Narratives………..……… 68

Table 4.1 Lexical Equivalences and Non-equivalences …….……… 75

Table 4.2 Lexical Equivalences and Non-equivalences in Two-part Verbs ... 83

Table 4.3 Lexical Equivalences and Non-equivalences in Three-part Verbs.. 85

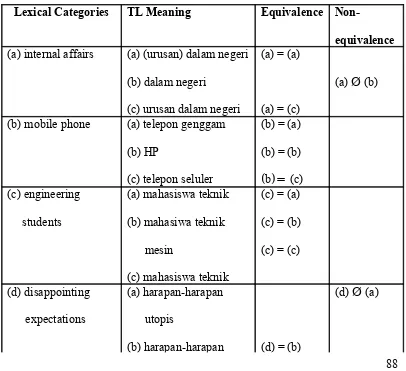

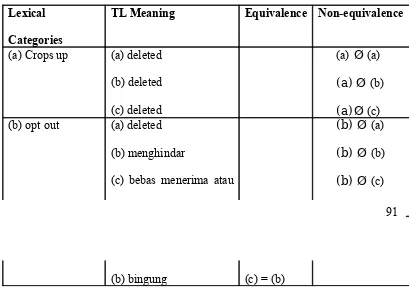

Table 4.4 Lexical Equivalences and Non-equivalences in Adverbs…………. 88

Table 4.5 Other Lexical Equivalences and Non-equivalences in Adverbs….. 91

Table 4.6 Lexical Equivalences and Non-equivalences in Adjectives………. 93

Table 4.7 Other Lexical Equivalences and Non-equivalences in Adjectives… 96

Table 4.8 Lexical Equivalences and Non-equivalences in Nouns……… 99

Table 4.9 Lexical Equivalences and Non-equivalences in Noun Compounds……… 101

Table 4.10 Another Example of Lexical Equivalences and Non-equivalences in Adjectives ………..………... 104

Table 4.11 Semantic Non-equivalence in OT1S23…..…...………….... 128

Table 4.12 Semantic Variability………... 135

List of Abbreviations

1. TE : Translation Equivalence 2. TNE : Translation Non-equivalence

3. ST : Source Text

4. TT : Target Text

5. SL : Source Language

6. TL : Target Language

7. 3G : Third Generation

8. PDA : Personal Digital Assistant

9. PC : Personal Computer

10. CCTV : Closed-Circuit Television

11. TLT1S2 : Target Language Text 1 Sentence 2 12. OT1S3 : Original Text 1 Sentence 3

13. OT1T : Original Text 1 Title 14. ET : Ekuivalensi Terjemahan 15. NET : Non Ekuivalensi Terjemahan

ABSTRACT

Anselmus Sudirman. 2007. A Study on Equivalence and Non-equivalence in English-Indonesian Translation. Yogyakarta: English Language Studies, Master Program. Sanata Dharma University.

Equivalence constitutes a phenomenon in the theory and practice of translation concerned with readability, clarity, and accuracy of the target language form and content. By principle, a change of the target language form and content – as the effect of translation – is considered as a linguistic fact that leads to lexical, grammatical and semantic elements. Translators attempt to recognize the differences within the source text and the target text by contextualizing word forms and their meanings. But the translation of both texts is considered lost if their form and content are ambiguous resulting in what is called non-equivalence.

This translation research is significant (1) to explain translation equivalence (TE) and translation non-equivalence (TNE) using text-centered and translator-centered approaches (Campbell, 1998) by which the source and target texts are analyzed in terms of lexical, grammatical and semantic elements; (2) to set strategies of translating a non-equivalent text; and (3) to treat with equivalences and non-equivalences as models that reflect translators’ attempts in bridging the gap between the source and target texts. Thus, two research questions arise: (1) What are kinds of equivalences and non-equivalences in English-Indonesian translation texts? (2) What are strategies translators used/adopted to maximize equivalences in English-Indonesian translation texts?

To answer these questions, the researcher deployed two methods of data collection. A narrative method was used to obtain linguistic data on equivalences and non-equivalences analyzed directly from the translated texts done by three translator respondents. Tape-recorded interview with the research respondents was performed to get information about their translation and to discover strategies they adopted/used to encounter non-equivalence problems in translating a text on technology. The purpose of tape-recording the interview was to elicit data accurately and originally. These interviewed transcripts were analyzed in the standpoint of a descriptive method.

The procedures used in this research are: (a) selected three translators from different background knowledge, (b) selected the text, (c) gave the text to translators, (d) asked translators to translate the text, (e) collected the translated texts, and (f) analyzed them to recognize translation equivalences and non-equivalences. The instruments used were documents and unstructured tape-recorded interviews with the translators to get ideas on translation equivalences or strategies to overcome translation non-equivalences.

This research yielded two salient results. First, all the translators left certain abbreviations of technological technical terms untranslated. Second,

although translators translated the same source text (English), they produced three Bahasa Inggris, Program Magister. Universitas Sanata Dharma.

Ekuivalensi merupakan sebuah fenomena dalam teori dan praktek penerjemahan yang terkait dengan keterbacaan, kejelasan, dan kecermatan bentuk dan isi bahasa sasaran. Pada dasarnya, perubahan bentuk dan isi bahasa sasaran – sebagai efek penerjemahan – dianggap sebagai fakta linguistik yang mengacu pada elemen leksikal, gramatikal dan semantik. Para penerjemah berusaha mengenal perbedaan-perbedaan dalam teks asli dan teks yang diterjemahkan dengan kontekstualisasi bentuk kata dan artinya. Tetapi, penerjemahan kedua teks itu dianggap menyesatkan bila bentuk dan isinya ambigu yang menimbulkan apa yang disebut nonekuivalensi.

Penelitian terjemahan ini penting (1) untuk menjelaskan ekuivalensi terjemahan (ET) dan non-ekuivalensi terjemahan (NET) dengan menggunakan pendekatan text-centered dan translator-centered (Campbell, 1998) dimana teks asli dan teks yang diterjemahkan dianalisis berdasarkan struktur kebahasaan, leksis dan semantik; (2) untuk menentukan strategi menerjemahkan teks nonekivalen dan (3) untuk membahas ekivalensi dan nonekivalensi sebagai model yang mencerminkan upaya para penerjemah dalam menjembatani celah antara teks asli dan teks yang diterjemahkan. Maka, dua pertanyaan penelitian muncul: (1) Apa jenis ekuivalensi dan nonekuivalensi dalam teks penerjemahan Inggris-Indonesia? (2) Apa strategi-strategi yang diadopsi/digunakan para penerjemah untuk memaksimalkan ekuivalensi dalam teks terjemahan Inggris-Indonesia?

Untuk menjawab pertanyaan-pertanyaan ini, peneliti menerapkan dua metode pengumpulan data. Metode naratif dipakai untuk mendapatkan data-data lingguistik mengenai ekuivalensi dan nonekuivalensi yang langsung dianalisis dari teks-teks terjemahan yang dilakukan oleh tiga responden penerjemah. Wawancara yang direkam dengan para responden penelitian dilakukan untuk mendapatkan informasi tentang terjemahan mereka dan menemukan strategi yang mereka adopsi/gunakan untuk mengatasi masalah-masalah nonekuivalensi dalam menerjemahkan naskah teknologi. Tujuan direkamnya wawacara tersebut adalah untuk memperoleh data-data yang akurat dan orisinil. Transkrip-tanskrip wawancara ini dianalisis berdasarkan metode deskriptif.

Prosedur-prosedur yang digunakan dalam penelitian ini adalah: (a) memilih tiga penerjemah dari latarbelakang ilmu yang berbeda-beda, (b) memilih teks, (c) memberikan teks itu pada para penerjemah, (d) meminta para penerjemah untuk menerjemahkan teks, (e) mengumpulkan teks-teks terjemahan, dan (f) menganalisisnya untuk mengetahui ekuivalensi dan nonekuivalensi penerjemahan. Instrumen yang digunakan adalah dokumen dan wawancara tak terstruktur yang

direkam dengan para penerjemah untuk mendapatkan gagasan-gagasan tentang ekuivalensi terjemahan atau strategi-strategi mengatasi nonekuivalensi terjemahan.

Penelitian ini menghasilkan dua hal penting. Pertama, semua penerjemah tidak menerjemahkan singkatan-singkatan tertentu yang terkait dengan istilah-istilah teknis dalam bidang teknologi. Kedua, meskipun para penerjemah menerjemahkan teks bahasa sumber yang sama (bahasa Inggris), mereka menghasilkan tiga teks bahasa sasaran dengan versi yang berbeda-beda (bahasa Indonesia). Dua hal ini diharapkan akan memberikan kontribusi berarti terhadap jenis-jenis ekuivalensi dan nonekuivalensi terjemahan.

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

The first chapter of this thesis consists of six sections. First, the

Background section elaborates the translation equivalences, non-equivalences, and strategies taken by translators to overcome non-equivalences. Second, the

Problem Identification section discusses concepts, factors, and variables used in identifying the research problem. Third, the Problem Limitation section highlights concepts, variables, and strategies of translation. The detailed information on the research questions, the design, or pattern of translation equivalences and non-equivalences and strategies applied in maximizing non-equivalences becomes part of the Problem Statement section. The fifth section on Research Goals presents types of equivalences and non-equivalences and the translation strategies. The Research Benefit in section six focuses on the advantages of this research in contributing something to the body of knowledge, academicians, and translators.

1.1 Background

Translation inevitably coincides with equivalences and non-equivalences. The practice of translation as coined by Duff (1989: 10-11) emphasizes two underlying principles. First, translation equivalences in terms of language form and content constitute the ordering of words and ideas that should match the

xv

original as closely as possible. Second, the meaning of the target text should reflect accurately the meaning of the source text. In this perspective, translators attempt to establish equivalences for the purpose readability, clarity, and accuracy of the source and target languages.

The articulation of translation focusing on the language form and the meaning is considered as a linguistic feature that puts into practice the analyses of lexical, grammatical, and semantic elements. In line with Duff’s emphasis, the change of language form linguistically modifies the content area of the translation because the consistency for accurately delivering message from the source text into the target text is of paramount importance.

The priority of conveying meaning should comply with accuracy and clarity no matter translation non-equivalences cannot match the differences within both texts. In other words, the unavoidable mismatch between the source text and the target texts is called non-equivalence that is widely known as “untranslatability” (Bassnett, 1988:32; Catford, 1965: 98). By applying equivalence-oriented (Vinay & Darbelnet in Leonardi, 2005) and text-centered approaches (Campbell, 1998), the untranslatable or non-equivalent words, and phrases can be traced from the standpoint of their lexical, grammatical, and semantic features. However, the blurred translation, as a direct impact of untranslatability should be handled using a translator-approach (Campbell, 1998) that traces back the translated texts involving translators.

The translators’ involvement is significant to clarify strategies used in dealing with translation non-equivalences particularly the transfer of meaning

xvi

from the source text into the target text. Translators’ task, therefore, is to convey the meaning as clearly as possible by reconstructing the linguistic form of the target text. According to Nida (1964: 13), the translator facilitates the transfer of meaning and linguistic elements from the source text into the target text and creates equivalent expressions. In this case, translation is not solely related with types of equivalences to cope with, but also the non-equivalences of the target language readers.

It is worth noting that the complexity of a source text to be translated (in this case a text on technology) is influenced by the “text-bound” (Duff, 1989) which is also called the text-meaning involving linguistic contexts of the target language. The term “text-bound” contains two domains, namely: (1) skills-reading that involves a comprehension on how to link the source text with the target text to achieve equivalent expressions; (2) writing which is time-consuming in hatching words or expressions to “govern the production and reception of translation” (Tianmin, 2006). For Duff, the transfer of meaning from the source text is influenced by the target text accuracy and clarity.

In line with the fact, a translation should produce a target text that communicates the meaning accurately. A translator, then, situates the source language text within the target language texts expressing words, phrases, and sentences based on the linguistic system of that language. Riazi (2003) suggests that to make the target text communicative, a translator should meet three requirements, namely (a) familiarity with the source language that requires translators’ competence, (b) familiarity with the target language that influences

xvii

the result of translation and (c) familiarity with the subject matters that demands vocabulary building, an adequate understanding, and competence in performing his/her job successfully.

The existence of translation, under such a circumstance, takes heed of equivalences. Zaki (2001) points out that translating in fact involves more than just finding corresponding words between two languages. A source language text does not only aim at conveying a meaning, but aspires to produce a certain impact on the readers using particular language style especially in a literary translation. The term language style refers to the common linguistic rules familiar to the target language readers which are linguistically and culturally specific.

The acceptability of the translation also depends on the equivalences (as the concern of this study) that bridge that gap between linguistic and cultural specificities. In this context, translation is becoming a more and more important means of enhancing linguistic and cultural understanding within the source and target texts. However, a certain cultural variety in the source text cannot be translated into the target culture as easily as the translator expects.

Wiersema (2004) underlines that cultures which readers are traditionally not familiar with have become more familiar because of globalization. The effect of globalized world at least influences translation especially an excessive one that fails to foreignize or excoticize, i.e., use source language terms in the target language text that is, to a certain extent, acceptable now.

In relation with this phenomenon, as what Wiersema concerns, a translator has three options for the translation of words that are left untranslated in the target

xviii

text. First, adopting the foreign words without explanation that make them unacceptable or acceptable. Second, adopting the foreign words with extensive explanations. Third, rewriting the text to make it more comprehensible to the target language audience. Thus, it is generally held that translation refers merely to an activity of treating untranslated words from a foreign language text – as its source text – into a first language text – as its target language (Ma’mur: 2005).

The translator will consequently find inexact meaning of the target text due to the stage of linguistic difficulty, as expressed by Baker (1992: 57) below:

A certain amount of loss, addition, or skewing of meaning is often unavoidable in translation; language systems tend to be too difficult to produce exact replica in most cases.

In line with this translation difficulty, Baker cites an example that an English term “good/bad law” is translated differently as “just/unjust law” in Arabic. What is essential from this example is not only about the accuracy of translation but also about the familiarity with the target text as well in communicating the message. Baker (1992: 57) describes further in detail in the following:

Accuracy is no doubt an important aim in translation, but it is also important to bear in mind that the use of common target language patterns which are familiar to the target reader plays an important role in keeping the communication channels open.

As to argue against Wiersema and Baker, Jacob (2002) criticizes that translation – no matter it encounters foreign words or not – should consist of

xix

giving linguistic expression in one language to a thought process that takes place in another. It looks for and uses what is judged to be the most appropriate way of re-verbalizing that thought to make the translated text naturally equivalent to the original. It means that translation constitutes a way of expressing equivalent words as closely as possible with the original text.

In line with Jacob, Thriveni (2002) suggests that in achieving such a translation phenomenon, a translator has to look for equivalents in terms of relevance in the target language. Nida (1964) as quoted by James (2002) emphasizes that equivalent expressions should deal with the target language form and content to help the target language readers understand the customs, manner of thought, and means of expressions in the source language context. It is the translators’ task to relate the receptor’s mode of behavior with the context of source language.

Whatever the equivalent words might be and what strategies used to overcome them, meaning is a central issue in translation as described by Al-Zoubi & Al-Hassnawi (2001:12) below:

Meaning should be the main preoccupation of all translation. However, the amount of this interest varies according to the type of meaning conveyed by the lexical items of a given text. As far as translation is concerned, the translator has to do his/her best to transfer as much of the original meaning as s/he can into the target language.

In searching for the meaning, translation often involves a tension or a difficult choice between what is typical and what is accurate (Baker, 1992: 56). The typicality refers to the target text specific meaning of registers produced in

xx

the context of its users only, and certain typical words cannot be used in the source text because of its inaccuracy to represent the same words. Accuracy refers to the exactness or correctness of words translated by which their original meanings are expressed clearly and the target reader finds the exact words expressions in the target text.

If there is an ambiguity in expressing meaning, the target text cannot convey the message of the original text as clearly as possible. The translator, then, fails to communicate the text meaning and, as a result, the text is untranslatable. As a solution, the source text should be judged in terms of its communicative function and there should be an equivalence to clarify the same communication in the target text. Zaky (2000:2) formulates it as the following:

In translation, consequently, the translator ought to translate the communicative function of the source text, rather than its significance. A translator must, therefore, look for a target language utterance that has an equivalent communicative function, regardless of its formal resemblance to original utterance as far as the formal structure is concerned.

In other words, the communicative function again depends on the translator’s familiarities, and competences in communicating messages from the source text into target text. How s/he chooses appropriate utterances that equivalently bridge such messages proportionately. The equivalence-oriented translation (Vinay & Darbelnet: 1995) as quoted in Leonardi (2000) deals with noun and adjective phrases and words arise from the situation, and it is in the situation of the source language text that translators have to look for solutions. Indeed, semantic equivalence of an expression found in the glossary is not

xxi

enough, and it does not guarantee a successful translation. The most important aspect to consider is the translators’ competence in translating a text contextually and accurately.

By applying equivalence-oriented translation, translators replicate the same situation as in the original while using completely different wording. In this perspective, translation task requires “the skill of information literacy” (Salvador: 2006) involving competence to digest the source text and reformulate it equivalently in the target text. The more words or expressions is equivalent with the source text, the better translation relevant to produce a communication that clarifies what message is meant to convey and how to make it acceptable in the target text.

The acceptability of a target text is in relation with linguistic accuracy, or standardized language use, and readers’ intelligibility. The study of equivalence is inevitably in favor of linguistic approach (lexicon, grammar, and semantics). In fact, the translator also faces two different cultures within the texts that uniquely represent a variety of specificities. To this extent, translating a text on technology emphasizes those differences. The truth is that every text rooted in the complexity of its linguistics as well as socio-cultural conditions is open to the equivalence or even translation lost. Translators have to deal with such differences for one purpose – communicating the message from the source text into the target text as clearly as possible.

In the process of translation, communicating the SL message clearly is fruitful for the target language readers to understand the source language. If the

xxii

translation is smooth, or particularly dynamic, the translated text seems likely an original one with a flow of ideas communicated fluently. In some cases, not every expression is equivalent because the translated texts describe neither naturalness nor specific cultural items in the original source texts. It is not merely the linguistic features of translation that make cultural transfer impossible to digest but also the target language receivers who are not accustomed to accepting translated words with their contexts of meanings.

Korah-Go (2005) points out that translation as such emphasize the transfer of messages or information (in a non-literary text) from the source language (English) into a target reader (Indonesian). It is the translators’ effort to transfer the message in the practice of translation as professionally as possible (ethics of profession). By the term ethics, translators assume responsibility whereas every single effort aims at dedicating what is so-called “qualified service” for customers.

1.2 Problem Identification

To identify the problem under study, a representation of methods is forwarded. First, the translation equivalence is an empirical phenomenon discovered by studying SL and TL texts (Catford, 1965: 27), and translation non-equivalence is a real phenomenon of mismatching between SL and TL texts. The underlying principle of text-centred approach, as Campbell (1998) is important to know the equivalences and non-equivalences involving lexical, grammatical, and semantic analyses. It provides an overview of the current trends in which such

xxiii

linguistic elements become an integral part of the source language and the target language. The absence of such elements results in translation non-equivalences that overlap the message from the source text into the target language.

Second, as to overcome the translation non-equivalence, the potential use of translator-approach (Campbell, 1998) is highly demanded. This approach is possible to get easy access to translators who adopt other translator experts’ translation strategies as required in handling untranslatability (non-equivalences), or they coin their own strategies (that are subject to emergent ones).

Some of the strategies used – as suggested by Wiersema (2004) – are: (1) adopting the foreign words without explanation that make them unacceptable or acceptable; (2) adopting the foreign words with extensive explanations; and (3) rewriting the text to make it more comprehensible to the target language audience. Baker (1992) coins some other strategies: (4) translation by omission, (5) translation by illustrations, and (6) translation by paraphrase using related/unrelated words. All these strategies are models that support the translation profession, translation studies, and qualified service and the fulfillment of knowledge.

The method used in this research is mixed. First, all the models as mentioned previously imply a quantitative method, but it is not meant to be statistically derived generalization because the translators – as shown in the interview narratives (Appendix 6: Interview Narratives) – are allowed to use emergent issues in overcoming non-equivalences from their own perspectives. Second, a qualitative method is used to analyze linguistic data from the translated

xxiv

texts. In general, the method used in this research is the qualitative one that presents in the form of words rather than numbers (Miles & Huberman, 1994: 1).

1.3 Problem Limitation

The effective use of text-centred approach yields different kinds of equivalences such as lexical equivalence, grammatical equivalence, and semantic equivalence. In semantic equivalence, for example, the translator seeks to translate the meaning of the original in such a way that the target language wording will trigger the same impact on the target culture audience as the original wording did upon the source language audience.

In this equivalence the form of the original text is changed, but as long as the change follows the rules of back transformation in the source language, of contextual consistency in the transfer, and of transformation in the receptor language, the message is preserved and the translation is faithful (Nida & Taber, 1982: 200) as quoted in Leonardi (2000).

If there are no longer expressions attained to preserve as many as equivalences as possible due to the fact that source language terms do not contain correspondent meanings partially or inexactly, there should be a translator-approach that takes heed of strategies set by experts or created by the respondents themselves.

Wiersema (2004) and Baker (1992) mention some of them: (1) adopting the foreign words without explanation that make them unacceptable or acceptable; (2) adopting the foreign words with extensive explanations, (3) translation by

omission, and (5) translation by illustrations. These strategies determine meanings in the target language that can be preserved or maximized equivalently.

It is known that equivalence-oriented (Vinay & Darbelnet in Leonardi 2005), and text-centered and translator-centred approaches (Campbell, 1998) are used to focus on attainment of lexical equivalence, grammatical equivalence and semantic equivalence because they are closely related to the analysis of lexical, grammatical, and semantic components within English and Indonesian texts. In the process of analyzing such components, the mismatching found between the source language and target language is called translation non-equivalence (untranslatability).

There should be solutions taken by contacting the respondents who are also professional translators. They set strategies particularly in line with non-equivalences based on their real experience of translating an English text on technology into Indonesian. However, this study is limited to the specifications of lexical, grammatical, and semantic equivalences in terms of equivalent or non-equivalent words, phrases, or even sentences which are translated typically and accurately.

1.4Problem Statement

In line with the background, problem identification, and the problem limitation, this research tried to answer the questions as stated below:

a. What are kinds of equivalences and non-equivalences in English-Indonesian translation texts?

b. What are strategies translators adopted/used to maximize equivalences in English-Indonesian translation texts?

The “kinds” as mentioned in (a) are sorts or varieties of translation equivalences and non-equivalences that can be found in English-Indonesian translated texts. The concept in (b) deals with strategies provided by the translators in overcoming translation non-equivalences.

In this case, a translation is in a state of non-equivalence if it has wrong, zero, or ambiguous meaning. As a result, the target language readers misunderstand the message of the translation. The reason is that the form of the language is preserved, but the meaning is lost or distorted (Nida & Taber, 1974).

Translators solve the problems by adopting strategies as required or they create their own strategies in tackling translation non-equivalences. Baker (1992: 26-42) mentions some of them: (1) translation using a loan word or a loan word plus explanation, (2) translation by omission, (3) translation by illustration. Wiersema (2004) mentions some others: (4) adopting the foreign words without explanation that make them unacceptable or acceptable; (5) adopting the foreign words with extensive explanations; and (6) rewriting the text to make it more comprehensible to the target language audience.

1.5 Research Goal

By taking into account linguistic features involving lexical, grammatical, and semantics and based on the problem formulation, this research is intended to describe the following goals:

1. To interpret kinds equivalences (lexical, grammatical, and semantic equivalences) and non-equivalences in English-Indonesian translated texts.

2. To describe strategies adopted by translators from translator experts as required and describe strategies they create to maximize equivalences in the English-Indonesian translated texts (emergent). Referring to such goals, the objectives of this research are to find out:

1. The kinds of translation equivalences (TE) and translation non-equivalences (TNE) in English-Indonesian translated texts.

2. The strategies adopted/used by translators to maximize equivalences in English-Indonesian translated texts.

3. The translators’ strategies that can be used by other translators in doing their profession.

1.6 Research Benefit

This research has significant contributions to the field of translation theory and practice as the following:

1. The description of equivalences is pivotal to (a) increase accuracy (precision) of lexicon, grammar, and semantics for either source or target languages, and (b) to increase translators’ understandings in dealing with translation equivalences.

2. The elaboration of non-equivalences strategies is important for translators to (a) overcome inaccuracy of translation, and (b) to figure

out non-equivalences (untranslatability) that makes the translation obscure.

3. The description (1) can be used by translators as kinds of equivalences in translation, and description (2) can be used by translators as non-equivalences strategies although their definition, relevance, and applicability within the field of translation (Leonardi, 2000) have been criticized.

CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

This chapter is divided into two main sections, Theoretical Review and

Theoretical Framework. In the Theoretical Review section, the discussion mainly focuses on the Translation, Equivalence, and Non-equivalence that become an integral part of the translation achieved by studying the SL and TL from the perspective of linguistic and extra-linguistic elements. Different kinds of non-equivalences that require translators’ strategies become a kernel of section

Translation Strategies, followed by the Translation Process section that emphasizes processes of translation. The Translation Norms and Quality Translation sections correlate with standards or policies and the quality of translation. A mélange of translations can be found in the Kinds of Translation

section and the Translation Studies section discusses issues related to translation as an academic discipline. The perspectives on overall theories above are elaborated in the Theoretical Framework section.

2.1 Theoretical Review

The theoretical framework in this chapter builds up the framework of thinking in accordance with translation equivalences, non-equivalences, and strategies adopted to maximize equivalences, their relationships, significant problems, related research findings, the researcher’s theoretical-based predictions to answer research questions and empirical evidence required.

2.1.1. Translation

Hatim and Munday (2004: 6) define translation as (1) the process of transferring a written text from the ST to the TT, conducted by a translator, or translators in a specific socio-cultural context; (2) the written product, or TT, which results from that process and which functions in the socio-cultural context of the TL; and (3) the cognitive, linguistic, visual, cultural, and ideological phenomena which are an integral part of 1 and 2.

Referring to these three definitions, translation is described not only in terms of transferring a written text but also the transfer of meaning from the source language into the target language. In other words, the same meaning in the source text is reproduced in the target text by using a new equivalent text. Such a definition is more complete as it involves the activity of reproducing meaning and looking for appropriate equivalent words in the target language. Thus, the translation generally aims at establishing equivalence relationships between the source and target texts to communicate the meaning. To make the delivered meaning acceptable, a translator takes into consideration a number of constraints including grammatical, and lexical rules of both languages, their context, their conventions, and so forth.

Jacob (2002) adds that the translator also has to adapt the message to the target audience and use only what s/he considers to be the most appropriate solution in any given situation. The ultimate aim is to communicate the message as effectively as possible. Again, communicating the message effectively to the target language readers is important in translating.

On the contrary, Webster’s Compact English Dictionary (2003) defines translation as an act of changing form from one state to another, to form into one’s own or another’s language. Thus, it is transparent that the concern of translation is on the change of form from the source text into the target text. The nature of form is of course attached to linguistic expressions using the actual words, phrases, clauses, sentences, etc. Nevertheless, the concern of translation is also on the meaning transfer. The reason is that the change of form influences the meaning.

Thriveni (2000) criticizes this definition by accentuating that translation is not simply a matter of seeking other words with similar meaning but of finding appropriate ways of saying things in another language. Another critic is Zaki (2001) who says that translating in fact involves more than just finding corresponding words between two languages. Words are only minor elements in the total linguistic discourse.

To argue against this idea, Hewson & Martin (1991:1) emphasize that translation is an ambiguous term that contains at the same time the idea of translation production. The ambiguity represents the complexity of the word “translation” as to refer to the real production of a translated text (TT) proposed as the translation of a source text (ST). Regardless of the ambiguity, Bassnett (1991: 13-15) points out that translation involves the transfer of meaning from the source text to the translated text.

In terms of the message produced, Nida and Taber (1974: 12) accentuates that translating must aim primarily at “reproducing the message”. However, to reproduce the message, the translator makes good grammatical and lexical

adjustments. The tendency is that in the first place, it may be said that each message, which is communicated, has two basic dimensions, length, and difficulty. In the original communication, which takes place within the source language, any well-constructed message is designed to the target language.

To make the original communication prevails, it is the content (meaning) that must be preserved at any cost; the form, except in special cases, such as poetry, is largely secondary, since within each language the rules for relating content to form are highly complex, arbitrary, and variable (Nida & Taber, 1974: 165). Nonetheless, the content of the source text should be reproduced by using an acceptable form of the target language appropriately.

The form of the texts is different, yet the translator should be careful with the content which is also significant to convey. Larson (1984: 3) as quoted by (Suwardi, 2005) emphasizes that translation refers to the form change from the source text into the target text, from a different form of language to another.

In translating a text, the form of the receptor language replaces the form of the source language. However, at the same time it communicates meaning. In this case, the purpose is to show that translation consists of replacing the form and transferring the meaning of the source language into the receptor language. This is done by going from the form of the source language to the form of the target language by way of semantic equivalence. As stated before, it is meaning, which is being transferred and must be held constant and only the form changes.

The semantic categories are also indispensable to make the transfer of meaning easy that cover three elements (Larson, 1984). First, the primary

meaning that is one-to one correlation between the form (lexicon and grammar) and the meaning (semantics). Second, the secondary meaning or figurative meaning in the translation of idioms, i.e. a string of words whose meaning is different from the meaning conveyed by the individual words. Third, meaning component in terms of morphosyntax that influences the translation of the source language text. Fromkin (2000: 340-348) emphasizes that the part of morphology that covers the relationship between syntax and morphology is called morphosyntax and it concerns with inflections and paradigms. An inflection refers to the changing of a word form or word ending to show its grammatical function (Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary, 1995). A paradigm is defined as a set of related word-forms with a given lexeme (Fromkin, 2000).

By that description, a good translation (Larson, 1984: 6) is characterized by three determinant factors. First, translation that uses the normal language forms of the receptor language. Second, it communicates, as much as possible, to the receptor language speakers the same meaning that is understood by the speakers of the source language. Third, it maintains the dynamics of the original source language text.

As to support that idea, a good translation (Larson, 1984: 3) also consists of studying of lexicon, grammatical structure (Frank, 1972: 231), communication situation, and cultural context of the source text, analyzing it to determine its meaning, and then reconstructing this similar meaning using the lexicon and grammatical structure that are appropriate in the receptor language and its culture context.

In fact, it is significant to explore cultural aspects in translation (Hewson & Martin, 1991: 25) since it explores a gap and of a tension between cultures. Its function is to develop cross-cultural constructions while at the same time bridging and underlining the differences. To make the translation adaptive to cultural difference (Nida, 1974: 12), the reproduction of messages in the receptor language should be close to natural equivalence of the source language message, firstly in terms of meaning and secondly in terms of form or style. As message is very important, therefore, translation aims at reproducing the message that requires cultural, grammatical, and lexical adjustments.

What Nida strongly emphasizes is about the translation equivalence. A translator reproduces the content in the translated text rather than the form of expressions. The forms are different (words, phrases), but the substance of the message remains stronger. Again, it is the message that should correspond to receptor’s language expressions. Nevertheless, the message transfer stagnates due to the state of being untranslatable. On the linguistic level, untranslatability occurs when there is neither a lexical nor a grammatical substitute in the target language for a source language item. It also occurs due to the absence of relevant situational features for the source language text in the target culture.

The acceptability of the translation involves culture, text difficulties, and linguistic facets that should be taken into consideration. More importantly, the absence of those elements results in generic-specific words that can become translation problems in the target language (Beekman and Callow, 1974: 185-186) as described in Larson (1984: 157): (1) the source language text may use a generic

term, but the receptor language may only have a more specific term in that semantic area, and (2) the source language uses a specific term, but the receptor language only has a generic word available in that semantic area.

Generic-specific words vary in different languages. In English, there is only one word for banana used for all varieties. In some other languages, there are a dozen of more specific names and there may or may not be a generic term. Indeed languages vary greatly in generic vocabulary but are more alike in specific vocabulary.

Larson (1984: 189) comments, however, that regardless of the generic vocabulary, translation is much more than finding words equivalent transferred from the source text into the target text. The source text structures must be abandoned for the natural receptor language structures without significant loss or change of meaning. With regard to what the fact is, the translator does not only pay attention to the structures, but the most important thing is how the language structures transfer messages from the source text into the target text.

In relation to that concept, today’s translation quality depends on the translator’s competence to create as many equivalent words as possible. Roberts as stated in (Ma’mur, 2005) mentions five competencies namely (a) linguistic competence, i.e. the ability to understand the source language and produce acceptable target language expression, (b) translation competence, i.e., the ability to comprehend the meaning of the source text and express it in the target text, (c) methodological competence, i.e., the ability to research a particular subject and to select appropriate terminology, (d) disciplinary competence, i.e., the ability to

translate texts in some basic disciplines such as economics, information science, and law, and (e) technical competence, i.e., the ability to use aids to translation like word processor, database, and internet.

In short, a translator should possess what Machali terms, good intellectual and practical devices. By doing so, “the chain of mediation and transfer of knowledge that makes up translation“ (Salvador, 2006) can be reached. In this connection, equivalences are vital to modify linguistic and cultural constraints of the target language.

It is in this context that the transfer of meaning determines the intelligibility of the translated text in terms of its equivalent words, phrases, sentences, or expressions. The target by which this is achieved maximally leads to the fact that translator has a purpose generally similar to, or at least compatible with, those of the original author (Hatim & Munday, 2004: 165).

Kompas (20/1/2006) mentions a translator’s competence in terms of the ability to translate that relies wholly on his/her experiences, talent, and common knowledge. Above all, the collaboration of knowledge or intelligence (cognitive), a strong feeling about the language (emotive), and the skill to use the language (rhetoric) is of paramount importance.

To conclude, the primary purpose of translation is to convey information as both content and form. The content refers to the message or meaning of a specific source text transferred to the target language. The intelligibility of the transfer process (translation) involves the form of the target language text with certain linguistic rules including lexical, grammatical, and semantic features.

Therefore, to make the translation communicative, adjustments is significantly required by combining both the form and content of the texts.

2.1.2 Equivalence

In the current perspective of English Language Studies, translation as a discipline of knowledge deals with double linkage equivalences (1) the linkage of words or phrases between the source text and the target text as closely as possible; and (2) the meaning of the target text that should correspond to the meaning of the source text accurately.

The concept in (1) leads to lexical and grammatical elements within both texts. The articulation of (2) is on the field of semantics that traces back the conveyance of meaning from the source language to the target language. Therefore, translators attempt to create an equivalence to establish translation readability, clarity, and accuracy (Duff, 1998).

Equivalence is defined as a central term in linguistic-based translation studies, relating to the relationship of similarity between ST and TT segments (Hatim & Munday, 2004: 339). It becomes a central term because the relationship of similarity in this context involves intra-linguistic criteria between the ST and TT. However, in maximizing equivalences, adjustment is required to convey the message from the source text into the target text. Moreover, awareness of the transferring message is important to make the text meaning intelligible in terms of words or phrases equivalent to the target language specificities.

In that perspective, Thriveni (2002:3) underlines the translator’s effort to create equivalences as explained below:

A translator has to look for equivalents in terms of relevance in the target language and exercise discretion by substituting rather than translating certain elements in a work.

It means that a source text is acceptable only if it has relevant equivalences in the target language. Substituting the text form of both texts is one of the strategies to create equivalences. As a result, s/he communicates the message transferred from the source language into the target language.

In line with communicating the message, Hervey & Higgins (1992: 22-23) coined a term called “communicative translation.” As the term indicated, the message or meaning is communicated to get equivalences. Although the form of the target language may be different from that of the source language, its message (meaning) is at least the same with the source text. The change of form within both texts is called translation shifts. In other words, Hatim and Munday (2004: 26) assert that the small linguistic changes that occur between ST and TT are known as translation shifts.

Catford (1965) mentions two types of translation shifts. First, level shifts (the source language item at one linguistic level, for example grammar, has a target language equivalent at a different level, for example, lexis). Second, category shifts that are divided into four types as described below:

First, structure-shifts involving grammatical change between the structure of the source text (ST) and that of the target text (TT). Second, class-shifts happen

when a source language (SL) item is translated with a target language (TL) item that belongs to a different grammatical class i.e., a verb in the SL may be translated with a noun in the TL.

Third, unit-shifts occur when the translation equivalence of a unit at one rank in the SL is changed into a unit at a different rank in the TL. In the translation between English and French, there is often a shift from MH (modifier + head) to (M) HQ (modifier) head + quantifier. E.g., A white house (MH) is translated as Une maison blanche (MHQ). This kind of unit-shift happens in the formal correspondence that is defined as “the general, systematic relationship between an SL and TL elements, out of context” (Hatim & Munday, 2004: 340). For example, there is a formal correspondence between this (a deictic) in English and este in Spanish. However, in the practice of translation este may be translated in another way.

Fourth, intra-system shifts occur when SL and TL possess system that approximately corresponds formally as to their constitution, but when translation involves selection of a non-corresponding term in the TL system. For example, the SL singular becomes a TL plural and vice versa.

From this description, it can be said that translation shifts or changes influence the creation of equivalences in relation with lexicon, grammar, and semantics. Lexicon is defined as a list of words (Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary, 1995). Baker (1992: 83; Frank, 1972) defines grammar as the set of rules that determines the way in which units such as words and phrases can be

combined in a language and the kind of information that has to be made regularly explicit in the utterances.

Translation equivalences cannot principally be reduced to a lexical element per se, but it covers the other elements as well. These are important to take into account in translating. House (1977) as quoted in Leonardi (2005) suggests that it is possible to characterize a target text by determining the situational dimension of the source text. It means that the source text is translated into the target text after a translator judges them on situational features.

Based on this fact, the translator relates linguistic features to the context (situation) of both source and target texts. An academic article, for example, has the same argumentative or expository force, but what to consider seriously is the effect of context of the translation itself that may be slightly different between the two texts. Thus, a translation text should not only match its source text in function, but employ equivalences in a situational dimension as well.

Baker (1992: 11-12) proposes two kinds of equivalences, namely (1) equivalence at word level, and (2) equivalence above word level. The translator takes into account the first equivalence as the first element in translation because s/he acknowledges the words as single units in order to find a direct equivalent term in the TT. The second equivalence refers to words conditioned by their specificities (idiom, grammar, etc) due to difficulties in translating them.

Larson (1984: 136) is in favor of the importance of equivalences by emphasizing that the translator involves “communication situation” in translating. It affects the diction or choice of vocabulary whereas different vocabulary can be

used in different situation and for different purpose. In certain situations, the translator should translate them smoothly to make them like the original text. Otherwise, s/he tends to use borrowed words, paraphrasing, and illustration when s/he finds no equivalent words or choice of words in the target text.

Baker (1992: 86) mentions a grammatical equivalence that affects the diversity of grammatical categories within the SL and TL with significant changes to come across as described below:

Differences in the grammatical structures of the source and target languages often result in some change in the information content of the message during the process of translation. This change may take the form of adding to the target text information which is not expressed in the source text. This can happen when the target language has a grammatical category which the source language lacks.

It is obvious that the grammatical structures within the SL and TL may change as the effect of translation. For example, the change occurs in grammatical devices such as number, tense and aspects, person and gender. The change also occurs in the grammatical equivalence of voice. The active voice in English is translated into passive in Indonesian. According to Chandra (1994) in (Wuryantoro, 2005: 132), passive voice is a form of verb which shows whether its subject is the doer of the action or something is done to it. Thus, passive voice refers to the sufferer or receiver of the action.

To support Baker’s grammatical equivalence, Nida (1964) as quoted in Central Institute of Indian Language (2006) categorizes three types of equivalences. First, a grammatical equivalence, which is classified as the

equivalence at the level of form and its focus, is on the form of the source text. This kind of equivalence is ST-oriented. Second, a dynamic equivalence that is not tied down to the ST form but it caters to the receptor’s linguistic and cultural needs. It is TT-oriented which allows adaptation/shifts in lexicon, grammar, and cultural information. Third, a semantic equivalence which is content-oriented by considering a TT in terms of linguistic criteria such as grammatical and semantic features and extra-linguistic ones like situation, subject field, TL readers, etc.

Nida & Taber (1982: 200) introduce a term “dynamic equivalence” to refer to the principle of “equivalent effect” that draws heavily on context, affects meaning and determines the translation (Hatim & Munday, 2004: 40 & 167). In this principle, the translator attempts to translate the meaning of the ST that gives rise to the effect of “context-bound of meaning”. It means that the meaning is put into the TT context although it is expressed in a different form of language.

The context of meaning is called “semantic variability” whereas a lexical unit may be justifiably said to have a different meaning in every distinct context in which it occurs (Cruse, 1986:53). The lexical unit here represents the translation of closed set items like affixes, markers, etc., and open set items such as nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs) that follow the TL contexts using a descriptive phrase in the receptor language (Larson, 1982: 151). It also designates content words (verbs, nouns, and adjectives) and function words (like on, in, or, at, to, with, etc). The content word has a lexical meaning while the function word has a grammatical meaning (Murcia and Olshtein, 2000: 76) as quoted in Imran (2005: 125). Fromkin (2000: 95) adds lexical categories such as open-class categories

(noun, verbs, adjective, and adverb) and closed-class categories (pronouns, determiners, etc).

In line with this context, Hatim and Munday (2004: 42) say that a dynamic equivalence caters for a rich variety of contextual values and effects that utterances carry within texts. They describe it in detail below:

That is, we opt for varying degrees of dynamic equivalence when form is not significantly involved in conveying a particular meaning, and when a formal rendering is therefore unnecessary (e.g. in cases where there is no contextual justification for preserving ST ambiguity).

It can be said that equivalences are approaches in translation. In applying them, the most important thing to concern is the meaning expressed in a different form (linguistic elements) of the target language. In addition, these approaches are not absolute but they are flexible for the individual translator in terms of how possible s/he can use them in translating.

If the translator uses one of the approaches, the equivalent effect is unavoidable. A principle generally known as the equivalent effect refers to an effect on the form of translation that is different from one translated text to the other. The form is different owing to the fact that both source and target languages are unique or specific in relation with their linguistic and cultural features. Whatever the differences are, the translation of the source language should produce the same effect on its target language audience.

In this case, translation – because of the differences between source and target language – will depend largely on the adjustment or adaptation factor (Nida

and Taber, 1969: 33) as quoted in (Hewson & Martin, 1991: 8-10). It means that the result of translation is more or less affected by adjustment of the target language forms and cultural contexts.

Regardless of the adjustment, to obviate foreign terms adopted directly from the source language into the target language, the translator can use a dynamic equivalence by which untranslatable terms or phrases are paraphrased. This happens in a dynamic or free translation involving the substitution of source text expressions contextually (Hervey & Higgins, 1992: 31, 248).

Larson (1984: 153) mentions a term called “lexical equivalents” divided into three categories. First, concepts in the source text which are known (shared) in the receptor language. Second, concepts in the source language which are unknown in the receptor language. Third, lexical items in the text which are key terms, translated using a special treatment. If this is the case, lexical equivalences help translators to bridge the gap between the source and target texts.

In addition, such lexical equivalents are also produced using a technique called transliteration. Hatim and Munday (2004, 353) define transliteration as the letter-by-letter rendering of the SL name or word in the TL when the two languages have distinct scripts. For example, the Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa promotes the use of the word “anggit” as the new equivalence of “concept”. However, Indonesian writers in general and Indonesian translators in particular avoid using this new equivalence because it is not familiar to the target readers. Instead, they use the old and popular transliteration “konsep” (Nababan, 2005: 17).

To conclude the translators’ effort to create translation equivalences results in the intelligibility of the message conveyance from the ST to the TT linguistically and contextually. Thus, translation equivalences including lexical, grammatical, and semantic equivalences are entrenched by the linguistic elements encompass lexicon, grammar, and semantics and their contexts in use.

2.1.3 Non-equivalence

Principally, there is another term in opposite to different translation equivalences called non-equivalence. It is defined as a state of being untranslatable because the target language does not match with the source language in terms of meaning, either partially or inexactly.

Non-equivalence often occurs if one or more of the vocabularies used are narrower in scope than the other vocabularies in either the source text or target text. In this case, a translation is in a state of non-equivalence if it has wrong, zero, or ambiguous meaning. As a result, the target language readers misunderstand the message of the translation. The reason is clear-cut. The form is preserved, but the meaning is lost or distorted (Nida & Taber, 1974). For example, ST: Cream tea (afternoon meal with tea to drink and scones with jam and clotted cream to eat). TT: Pasticcera (Italian) means pastry (only a type of food).

As a conclusion, non-equivalence is defined as a state of untranslatability in terms of words, phrases, and sentences. Therefore, translators attempt to set strategies to deal with non-equivalences that bridge that gap between the ST and TT. The underlying principle is that the translation is acceptable if it optimizes the

creation of equivalences, for example, by adapting the ST meaning to its context in the TT that is useful for the audience.

2.1.4 Translation Strategies

There are different strategies taken by translators in dealing with kinds of non-equivalence as mentioned by Baker (1992: 31- 42) namely, translation by cultural substitution, translation using a loan word or loan word plus explanation, translation by paraphrase using a related word or unrelated word, translation by omission and translation by illustration.

Translation by cultural substitution is a strategy in terms of replacing culture-specific item or expression from the source language into the target language. The immense advantage of using this strategy is that it gives the reader a concept with which s/he can identify – something familiar and appealing. On an individual level, the translator’s decision to use such a strategy will depend on (a) how much license is given to him/her by those who commission the translation, and (b) the purpose of translation.

In this perspective, cultural aspects complicate translation if the translator has no good command of cultural assumptions including indigenous terms, naming things, norms of translation, linguistic richness prevailing in a given community and words that are commonly known in one culture but generally unknown by the layperson in another culture.

The standpoint is that translation is not just a movement between two languages but also between two cultures. For example, cultural transposition is