Edited by Marie Segrave

|

M

A

USTRALIAN

&

N

EW

Z

EALAND

C

RITICAL

C

RIMINOLOGY

C

ONFERENCE

2009

C

ONFERENCE

Published by:

Criminology

School of Political & Social Inquiry Faculty of Arts

Monash University December, 2009

http://www.arts.monash.edu.au/criminology/

Publication data

Title Details: Title 1 of 1 - Australia & New Zealand Critical Criminology Conference 2009

Subtitle: Australia & New Zealand Critical Criminology Conference 2009: Conference Proceedings ISBN: 978-0-9807530-0-4

Format: Online

Publication Date: 12/2009

Subject: Criminology and Law Enforcement Editor Marie Segrave.

Australia and New Zealand Critical Criminology Conference 2009

Conference Proceedings

CONTENTS

Foreword 5

Sentencing Indigenous Resisters as if the Death in Custody Never Occurred

Thalia Anthony 6

Prisons and Vulnerable Persons: Institutions and Patriarchy

Eileen Baldry 18

Mainstreaming Problem-Oriented Justice: Issues and Challenges

Lorana Bartels 31

Surviving Outside: Bearing Witness to Women’s Post-Release Experiences of Survival and Death

Bree Carlton & Marie Segrave 41

Police Bail Decision-Making in Victoria: Private Decisions, Public Consequences

Emma Colvin 51

Intelligence Support to Law Enforcement: Untangling the Gordian Knot

Jeff Corkill 60

Identifiable, Queer and Risky: The Role of the Body in Policing Experiences for LGBT Young People

Angela Dwyer 69

‘Till Death Do Us Part: Judging the Men Who Kill Their Intimate Partners

Kate Fitz-Gibbon 78

Non-Transparent Justice & the Plea Bargaining Process in Victoria

Asher Flynn 88

Multiple Punishments: The Detention and Removal of Convicted Non-Citizens

Michael Grewcock 101

Stranger Danger? Cultural Constructions of Sadistic Serial Killers in US Crime Dramas

Annette Houlihan 111

Integrating Restorative Approaches In Victims’ Compensation and Assistance

Tyrone Kirchengast 122

Confidence in Justice Systems: Assessing Public Opinion

Murray Lee 132

Vigilantes Unmasked: An Exploration of Informal Criminal Justice in Contemporary South Africa

James Martin 142

Precrime: Imagining Future Crime and a New Space for Criminology

Jude McCulloch 151

The Best Police Force Money Can Buy: The Rise of Police PR Work

Alyce McGovern 163

Trafficking Reconsidered: A Gaze into a Crystal Ball and Ways Forward

Sanja Milivojevic 171

Returning to the Practices of our Ancestors? Reconsidering Indigenous Justice and the Emergence of Restorative Practices

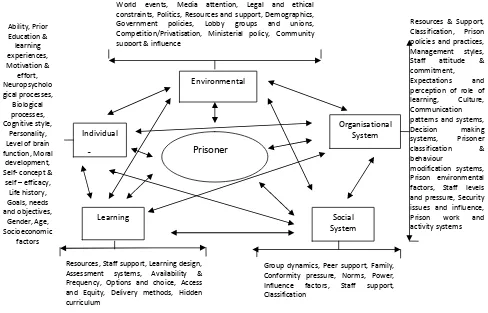

Outside The Curriculum: Informal Learning in Prison

Miriam Scurrah 194

Illegal Labour & Labour Exploitation in Regional Australia

Marie Segrave 205

The Construction of the Racially Different Indigenous Offender

Claire Spivakovsky 215

Bail in Australia: Legislative Introduction and Amendment Since 1970

Alex Steel 228

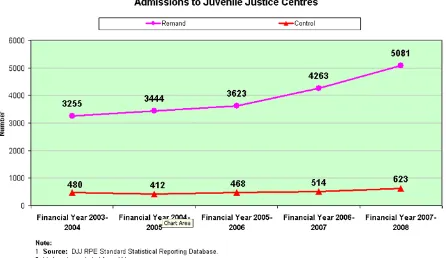

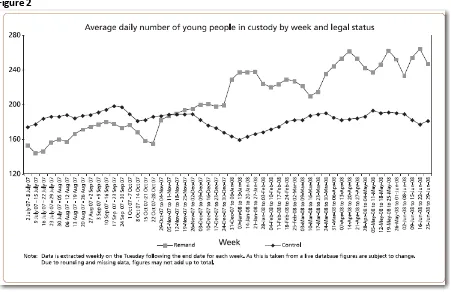

Critical Reflections on Bail and Remand for Young People in NSW

Julie Stubbs 244

Representations Of Indigenous Offenders: The ‘Gang Of 49’- A Media Drive By?”

Laura Swanson 258

Victimhood, ‘Sexual Deceit’ and the Social Origins of the Criminalization of HIV Transmission

Stephen Tomsen 266

Vigilantism, the Press and Signal Crimes 2006-2007

Ian Warren 275

Punitive Rehabilitation in New South Wales: New Developments in Community Corrections

Denise Weelands 285

Waste Not, Want Not: Externalising Environmental Costs and Harms

Foreword

The 2009 Australia & New Zealand Critical Criminology Conference cemented this event as an important

annual forum. Since the inaugural 2007 gathering in Sydney the ANZ Critical Criminology Conference has

continued to build momentum within and beyond Australia. For 2009 the conference was held in

Melbourne and hosted by Monash University Criminology. The diverse breadth and scope of critical

criminological research in Australia and New Zealand was evident in the fifty papers presented by

researchers to an audience of one hundred academics, researchers, policy makers, advocates and

students. The gains of critical criminology across Australia and New Zealand were further showcased by

the launching of four monographs over the course of the two day conference: Anna Eriksson’sJustice in

Transition (Willan); Stephen Tomsen’s Violence, Prejudice and Sexuality (Routledge), Elizabeth Stanley’s

Torture, Truth and Justice (Routledge) and Marie Segrave, Sanja Milivojevic & Sharon Pickering’s Sex

Trafficking (Willan).

This collection of papers is testamount to the expanding reach of critical research and, importantly,

brings together the work of emerging and established acamedics to reflect the many directions in which

critical criminology is moving.

We extend our thanks to all contributors to this collection and acknowledge with gratitude all referees

who reviewed papers, including: Alex Steel, Eileen Baldry, Bree Carlton, Sharon Pickering, Anna Eriksson,

Danielle Tyson, Michael Grewcock, Julie Stubbs, Rob White, Caitlin Hughes, Thalia Anthony, Annette

Houlihan, Tracey Booth, Stephen Tomsen, Rob White, Sanja Milivojevic, Elizabeth Stanley, Leanne Weber,

Harry Blagg and Murray Lee.

Marie Segrave, Dean Wilson & Jude McCulloch

Critical Criminology Conference Convenors 2009

Sentencing Indigenous resisters as if the death in custody never

occurred

Thalia Anthony, Sydney University

1Abstract

This paper addresses the trends in sentencing by higher courts of Indigenous protesters against ‘white’ racist violence. It contrasts earlier sentencing decisions affecting resisters on the Yarrabah Reserve in 1981 and towards the 1987 death in custody of Lloyd Boney at Brewarrina (NSW), with later sentencing of protesters after Mulrunji’s death in custody on Palm Island in 2004. It argues that Indigenous resisters are increasingly characterised by sentencing judges as out-of-control rather than capable of legitimate political engagement. This dovetails a denunciation of the Indigenous community in media moral panics that demands more punitive restraint.

Introduction

Criminal sentencing has been a space to recognise Indigenous factors in the criminal justice system.

Sentencing judges have taken it upon themselves to identify Indigenous factors for mitigating a sentence.

They have identified cultural expectations, community dysfunction and racial conflict as potential

grounds for mitigation.

However, Indigenous recognition in sentencing is an invariably limited space in the white criminal justice

system. This is, first, because the Indigenous person has already been subjected to the punitive aspects of

criminal procedure and been determined guilty. Therefore, sentencing only offers limited relief. Second,

mitigation is an exercise of paternalism. Douglas Hay (1975) has noted that sentencing judges use mercy

to demand gratitude from the dispossessed classes, which are otherwise subject to coercion. Third,

recognition is prone to shifting ‘white’ perceptions of whether Indigeneity is grounds for mitigation or

aggravation. Again, Douglas Hay suggests that sentencing judges rule through keeping the dispossessed

guessing whether they will exercise leniency or coercion.

The changing recognition of Indigenous factors in sentencing by higher courts is apparent since the 1990s

in relation to so-called ‘riot’ offences after a death in custody or ‘white’ racism.Because there is now a

view that Indigenous people belong to dysfunctional and out-of-control communities, the riot is treated

by sentencing judges as an irrational and unreasoned act, whereas previously greater attention was given

to how the white system contributed to Indigenous peoples’ acts of violence. Indigeneity is now grounds

1

for aggravation in a riot offence. However, even when it was grounds for mitigation in the 1980s, the

narrow understanding of Indigenous circumstances was posed the explanation in terms of the personal

stress of the Indigenous offender rather than their political purpose, with the exception of Justice

Murphy of the High Court.

In more recent criminal sentences, Indigenous resisters are receiving increasingly punitive sentences that

both reflect the moral panics in the media, as well as help create moral indignation towards Indigenous

communities and absolve the wrongdoing of the police in precipitating the riot. The police officer

becomes the ideal victim. The image and deemed offence of the riot represents a chaotic spontaneity

that undermines a ‘reasoned response’ to discriminatory policing (Scraton 2007). It removes questions as

to why the act occurred and, as Chris Cunneen (2007:23) argues, promotes a narrative of ‘blind lawless

purposelessness’. As Andy Gargett (2005:9) notes, the overarching portrayal of Indigeneity as criminal

‘reduces the riot to acts of criminality, rather than acts of desperation or frustration’. This view is

perpetuated by the trial and sentencing judges in the cases involving the so-called rioters.

‘Entitled to be an agitator’: Neal v The Queen (1982) 149 CLR 305

The only opportunity the High Court has taken to consider Indigenous sentencing factors was in the case

of Neal v The Queen (1982). It involved a confrontation between Collins, a non-Indigenous officer of the

Department of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, and the accused, Percy Conrad Neal, the

elected Chairman of the North Queensland Yarrabah Community Council, over Aboriginal

self-management of the Reserve.

The sale of rotten meat to Aboriginal people in 1981 was the final straw. With 12 other Aboriginal people,

Neal sought out the chief Government officers of the reserve. He found Collins, who was also the store

manager. After an argument about the management of the reserve, Mr Neal swore at Collins, told him

that he was a racist and that he and all the other “whites” should get off Yarrabah reserve (Neal v The

Queen 1982:321). He then spat in Collins’ face. Neal was convicted of unlawful entry and assault (through

Neal’s trial and appeal to the Qld Criminal Court of Appeal

Neal was sentenced by a Cairns magistrate to imprisonment for two months. The Magistrate was critical

of the act against the white officer: ‘Violence is something in recent times which has crept into Aboriginal

communities. I blame your type ….’ (cited in Neal v The Queen 1982:325). He went on to criticise the

political resistance, ‘Your actions in taking unto yourself the task of removing all whites from Yarrabah

cannot be condoned from any angle’ (cited in Neal v The Queen 1982:325).

Neal applied to the Queensland Court of Criminal Appeal and his sentence was actually increased to six

months imprisonment. The Court referred to the 12 youths with Neal as ‘a mob’, although at no time

were they present on the officer’s property (cited in Neal v The Queen 1982:313).

Neal HCA: critiquing magistrate’s comments

On appeal to the High Court, the magistrate’s two month sentence was reinstated. Although two of the

four judges, Gibbs CJ (Neal v The Queen 1982:307) and Wilson J (Neal v The Queen 1982: 320), allowed

Neal’s appeal on the technical basis that the Court of Appeal was acting ultra vires, all judges accepted

that the lower courts should take into account the racial tensions on the reserve.

Justice Brennan focused on the ‘emotional stress’ created by the racial tensions on the ‘paternalistic

system’ of the reserves (Neal v The Queen 1982: 325). Wilson J (Neal v The Queen 1982: 320) similarly

noted that Neal’s conduct was a result of the ‘frustration and emotional concern engendered in him by

the manner in which the reserves were administered and his endeavour to obtain self-management’.

Brennan J (Neal v The Queen 1982: 324-325) explained that the facts of the case pointed to ‘special

problems’ which may explain — though could not justify or excuse — Neal's conduct.

Justice Murphy is more forthcoming in suggesting that ‘Aborigines have a right to participate in and direct

their own policies’ (Neal v The Queen 1982: 318) and protest against the ‘reserve conditions and race

relations’, which are to be treated as special mitigating factors in a sentence. He cites the United States

experience, where ‘persons frustrated by powerlessness through the exercise of racist policies and

practices ... sometimes express [grievances] in the only way possible — by protest or violence’ (Neal v

If [Neal] is an agitator, he is in good company. Many of the great religious and political figures of history have been agitators, and human progress owes much to the efforts of these and the many who are unknown. … That is the reason why agitators are so absolutely necessary. … Mr. Neal is entitled to be an agitator (emphasis added, Neal v The Queen 1982: 318).

Although Murphy’s view was the exception on the Bench, it provided a solid enunciation of sentencing

mitigation. The weaker, individualised enunciation of Indigenous factors by Brennan and Wilson JJ

prevailed. However, sympathy towards the Indigenous individual would transform into disdain towards

the ‘out-of-control’ Indigenous individual.

Brewarrina death in custody and sentencing context

In 1991 the New South Wales Court of Criminal Appeal reviewed the sentences of Aboriginal people

convicted of riot offences after the death in custody of Lloyd James Boney in 1987 in Brewarrina. Boney

was a 28-year-old Aboriginal man who was found hanging by a football sock in his police cell 1½ hours

after he was arrested for breaching bail conditions.

After the death in custody, the Aboriginal community accused the police of killing Boney (Wootten

1991:1). The view was that it was physically impossible for Boney to kill himself while heavily intoxicated

and nonetheless he was not inclined to commit suicide. The community was also outraged with the police

insensitivity in removing his body to Bourke before notifying his family of his death (Wootten 1991:1).

Less than a week after the death, the investigating police and NSW Police Minister reported that Boney

had committed suicide without any foul play on the part of the police. This occurred after an internal

investigation that was conducted overnight and involved only one officer being interviewed. There were

criticisms of police investigating police, cover-ups and fabrications of evidence, which were later

confirmed by the coroner.

Brewarrina Riot

In the week following Boney’s death, protests outside the police station gathered momentum. They were

all the more powerful because the Committee to Defend Black Rights had been monitoring deaths in

custody over eight months and found an average of one death every 11 days. The Committee was calling

on the Federal Government to initiate a Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. Within a

The so-called “riot” occurred at Boney’s wake. The police flouted an agreement between Western

Aboriginal Legal Service and a non-Aboriginal police liaison officer to steer clear of the wake. At the wake,

eight officers armed with riot shields, batons and helmets provoked about 20 mourners to fight (Pitty

1994). They became armed with iron bars and fence posts and shouted, ‘Black people have been killed by

white people for more than 200 years’ (Lewis 1991:3). The riot lasted about 40 minutes; four police

officers and numerous Indigenous people were injured (Hewett 1987:1). The ‘riot’ led to the arrests of 17

people, labelled the Brewarrina 17.

Moral panic – Brewarrina; complex narratives

The riot attracted headlines such as ‘Blood on the Street: the Night a Town Exploded’ (Hewett 1987a:1).

The rioters were represented as drunks and images of beer bottles stacked in the park were televised.

The response of the riot police was depicted as normal and legitimate. During the trials of the Brewarrina

17, the riot was televised repeatedly and omitted footage of police beating Aboriginal people in the park

(Morris 2001).

However, embedded in the media reports was that Boney’s death in custody had been a major factor in

the riot. The media was also critical of some of the police accounts. In the back pages of the Sydney

Morning Herald, an unnamed journalist pointed to the riot as an act of resistance to the death in custody,

poor living conditions, and 200 years of Aboriginal abuse (Anon 1987: 16). The journalist describes the

violence as that ‘practised by oppressed groups at "the end of their tether"’ to beg ‘the dominant group

to take notice of their inhuman plight’ (1987: 16).

Brewarrina Trial judge’s findings

At first instance, in trying and sentencing two deemed protagonists in the riots, Sonny Bates (Boney’s

brother-in-law) and Arthur Murray (an Aboriginal elder who was a campaigner for the Royal Commission

and whose son had died in police custody), District Court Judge Nash, amplified the perception of

Aborigines as violent, unpredictable and unstable (Morris 2001). He refused to refer to the death in

custody as a contributing factor to the violence. Boney’s death, however, could not have been clearer. On

down his report on Lloyd Boney’s death, recommending disciplinary action against the officers (Hope

1991:2).

The trial led to the convictions and imprisonment for riotous assembly and assaulting police (Lewis

1991:3; Lewis 1991b:3), despite evidence that Bates was violently attacked by the police and otherwise

played no role, and Murray had tried to stop the confrontation with the police (Pitty 1994). District Court

Judge Nash sought to defend the police in the trial and influence the jury regarding the guilt of the

rioters. Justice Nash ordered the jury to ignore media reports about the Black Deaths in Custody Royal

Commission, particularly the findings on the death of Lloyd Boney’s death (Lewis 1991a:6).

In sentencing the Murray and Bates, the judge presented them as responsible for disturbing the harmony

in the community by encouraging hatred of police. Nash J stated with a nostalgia for the virtuous past of

racial segregation, that in the 1950s and 1960s the ‘court sat only once per month and it was largely

white people who were accused’, whereas in the 1970s as living conditions improved and Aboriginal

rights were asserted, race relations changed for the worse. After pointing to the downfall of the previous

harmony, the judge said that ‘Aborigines’ [sic] are now attacking police, which ‘could only be described as

a completely unprovoked and violent riot’ (emphasis added) (Lewis 1991b:3). This was, according Nash J,

an alcohol-fuelled ‘half-hour of madness’ (Lewis 1991b:3).

NSW Court of Criminal Appeal sentencing decision

The accused appealed to the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal against the conviction on the basis of Justice

Nash’s bias to the police role at trial, and against the sentence for not accounting for the death in custody

as a mitigating factor. Their appeal was upheld and their convictions of riotous assembly and assault were

set aside (Curtin 1992: 7). Chief Justice Hunt was strongly critical of Justice Nash who, on

cross-examination, ‘actually helped a police officer’ and who in summing-up gave an ‘unhelpful review of the

evidence’ that ‘weighed unfairly against the accused’ (Curtin 1992:7; Voumard 1992:10).

The Court of Criminal Appeal recognised Indigenous disadvantage and the death in custody as relevant

It would have been quite unrealistic for the jury to have considered the specific blows alleged to have

been inflicted by each of the accused upon which the riot charge was based without knowledge of the

initial reason for which the crowd had gathered (following the funeral of the Aboriginal man who died

in police custody) (R v Murray 1991: 9).

The Court not only mitigated the sentence of Bates and Murray, but set aside both riot and assault

convictions for lack of evidence of identity despite abundant evidence of the police injury and the nature

of the offence. In other sentences, such as that of Glen Boney, Lloyd Boney’s brother, the Court of

Criminal Appeal identified the death in custody was identified as a relevant factor.

Palm Island death in custody and sentencing without context

The clearest expression of the demotion of the death in custody as a sentencing factor was in the

sentencing of the Palm Island protesters after the death in custody of 36-year-old Mulrunji. The

circumstances of the death were that Senior Sergeant Hurley arrested and detained Mulrunji, who had

almost no criminal record, for offensive language on 19 November 2004. Forty minutes after his arrest

Mulrunji was dead in a Palm Island police cell. The injuries he sustained in custody were a black eye, four

broken ribs, and a ruptured liver and portal vein. The ensuing investigation was conducted by mates of

the responsible officer, Sergeant Hurley. The community was told following the investigation that

Mulrunji had slipped on a step.

The community anger to the death in custody and prejudicial investigation culminated in a public protest.

On 26 November 2004 approximately 300 people (one-eighth of the Palm Island population) assembled

at the police station demanding that the police leave. The group threw stones and mangoes at the police

building and yelled abuse at the police. The Queensland Government’s response to the protest was to

declare a ‘state of emergency’ on the Island, evacuate medical and teaching staff and send 80 Tactical

Response Group Commandos to the Island (Hunter 2005).

The police officers were pointing rifles to the Palm Island protesters and prepared to fire on them to

preserve their own life (R v Wotton 2007: at 7). The officers ultimately retreated to the hospital and

part of a fairly modest complex of prefabricated buildings’, burnt down (Levitt 2008). Some officers

sustained minor injuries but there were no serious injuries.

Moral Panics relating to the Palm Island melee

The protest on Palm Island flooded the national mainstream media. It was portrayed as an impulsive

event that was incited by a ‘mob’ of rioters. In its coverage, the Australian media made no reference to

the partial investigation into the death in custody and scant reference to the death in custody itself. It did

focus on the pathos of the community and its living conditions. The media did not refer to historic

tensions in police-Indigenous relations. Headlines such as ‘Palm Island erupts’ (Mancuso & Connolly 2004)

and ‘Palm Island Explodes: Anarchy on Palm Island on knife’s edge overnight’ (Lineham and Seeney

2004:1) cast the rioters as uncontrollable and irrational; without cause or reason.

The Queensland Police Union (2005: 26), Queensland Police Commissioner and the Queensland

Government ran a concerted campaign to defend the police officers’ role in the riot (Eastley 2004; Pavey

2004). This went hand in hand with the Police Union’s campaign to absolve Hurley of any wrongdoing

associated with Mulrunji’s death in custody (Willoughby 2007: 4).

Sentencing of Lex Wotton

Lex Wotton was regarded as the ringleader of the riot. The 37-year-old was a long-term Indigenous

activist. The criminal justice system sought to make an example of him by handing down the harshest

sentence. In late 2008, four years after his act of resistance; after a barrage of adverse media and police

union publicity on the riot; after judicial remarks on Wotton’s culpability and moral wrongness

throughout his preliminary proceedings; and after the acquittal of Sergeant Hurley for the manslaughter

of Mulrunji, Shanahan J of the Townsville District Court sentenced Wotton to six years imprisonment.

In his sentencing remarks he disavowed the context of the death in custody and the mishandled

investigation, and focused instead on deterrence and the seriousness of the offence, especially as police

officers were victims. A significant sentencing consideration was the vindication of the police who were

The judge held that the ‘riot’ was so ‘intrinsically dangerous’ that circumstances such as Mulrunji’s death

did not warrant consideration (R v Wotton 2008: 5). He followed the position of the Court of Appeal that

reviewed the sentences of other Palm Island ‘rioters’. The Court of Appeal held that,

[T]he background [ie the death in custody] to this matter is not particularly relevant for the purpose

of the sentence. The reason for that, in my view, is the serious nature of the offence itself, rioting

with destruction (cited in R v Wotton 2008: 4).

Also following the Court of Criminal Appeal, Shanahan J positioned the offence not in Palm Island’s

context but in ‘recent and not so recent world history’ that ‘illustrates the immense damage wrought by

riots’ (R v Wotton 2008:6, emphasis added). Shanahan J remarked that ‘mob conduct’ and descent ‘into

lawlessness’ is not ‘tolerated in a civilised community’ that requires a reasoned response (R v Wotton

2008:6). The sentence was therefore to be increased with regard to general deterrence.

Despite the fact that no police officers sustained serious injuries (which may be contrasted with the

Brewarrina protest), seriousness was the major consideration in handing down the sentence. Justice

Shanahan noted that it was the police ‘identity of the targets of this violent riot which renders the

involvement of anyone in it, distinctly grave’ (R v Wotton 2008:5). In this way, sentencing added to the

perception of the police as victims rather than perpetrators of the death in custody and racial violence.

Concluding remarks

The sentencing of Indigenous resisters over the past 20 years shows, first, that recognition of Indigeneity

in sentencing is as much prone to leniency as it is to punitive condemnation. Both sentencing stances are

processes of control that denies plurality of sovereign systems and demands genuflection to the judge.

Second, we see in decisions since 2004 a renewed emphasis on the seriousness of the offence in

sentencing. The focus on the offence rather than the reason demonises Indigenous people as criminal

and situates the police in the position of the victim. The characterisation of unreasonably violent

Indigenous people not only excuses the police role in the death in custody, but exculpates them from any

acts of valorising the police, such as awarding them bravery awards after all the mentioned Indigenous

protests.

The shift away from a consideration of the causes of the ‘riot’ in sentencing dovetails the growing moral

indignation towards Indigenous communities over the past 20 years. Communities are perceived to have

failed because they could not be tamed by white policies. The ‘riots’ are used as symbols of an out of

control Indigenous community, which require infinitely greater controls in the fashion of law and order.

Deaths in custody and police violence are mere collateral damage for police who are attempting to

impose this control. The Indigenous response to these deaths is constructed in a way that allows further

control by the Anglo-Australian criminal justice system.

The alternative for sentencing judges would be to see the white legal system as a culture that is itself out

of control; as a culture that allows acts of murder without redress and diminishes Indigenous community

strengths. But this would undermine the role of the sentencing judge, which is, in the words of Douglas

References

Anon. 1987 'A riot at Brewarrina' Sydney Morning Herald 18 August p16.

Cunneen C 2007 'Riot, Resistance and Moral Panic: Demonising the Colonial Other' in Outrageous! Moral Panics in Australia S Morgan (ed) ACYS Publishing Hobart.

Curtin J 1992 'Riot verdicts set aside on appeal' Sydney Morning Herald 7 April p7.

Eastley T (2004) 'QLD police commissioner defends Palm Island response' Australian Broadcasting Corporation

30 November.

Gargett A 2005 'A Critical Media Analysis of the Redfern Riot' Indigenous Law Bulletin vol 6 no 10.

Hay D 1975 Albion's fatal tree: crime and society in eighteenth-century England Pantheon Books.

Hewett T 1987 'Race Riots: more towns are at risk' Sydney Morning Herald 18 August p1.

1987a 'Blood On The Street The Night A Town Exploded' Sydney Morning Herald 17 August p1.

Hope D 1999 'Call to discipline police over Aborigine's death' Sydney MorningHerald 10 April p2.

Hunter C 2005 'Palm Island: the truth behind the media portrayal – an interview with Erykah Kyle, Chairperson

of the Palm Island Aboriginal Council' Indigenous Law Bulletin vol6 no12.

Levitt S 2008 'The Sentencing of Lex Wotton' The Law Report Online:

www.abc.net.au/rn/lawreport/stories/2008/2416076.htm.

Lewis D 1991 'Two Found Guilty Over Brewarrina Funeral Riot' Sydney Morning Herald 17 April p3.

1991a 'Funeral riot: Jury told to ignore cell deaths report' Sydney Morning Herald 13 April p6.

1991b 'Black's behaviour has deteriorated: Brewarrina riot judge' Sydney Morning Herald 9 May p3.

LinehamS & SeeneyH 2004 ‘Palm Island Explodes: Anarchy on Palm Island on knife's edge overnight’ Townsville Bulletin 27 November p 3.

Mancuso R & Connolly S 2004 ‘Palm Island erupts: buildings burn, police threatened’ Australian Associated Press 26 November.

Morris B 2001 'Policing racial fantasy in the Far West of New South Wales' Oceania vol 71 no 6 pp242-262.

Pavey A 2004 'Beattie defends police tactics in island riot' Australian Associated Press 29 November.

Pitty R 1994 'Brewarrina Riot: the Hidden History' Aboriginal Law Bulletin vol51.

Queensland Police Union 2005 Police Journal July.

Scraton P 2007 Power, Conflict and Criminalisation Routledge London

Voumard S 1992 'Convictions Over Riot Set Aside By Judge' The Age 7 April p10.

Wootten H 1991 'Report of the Inquiry Into the Death of Lloyd James Boney' Royal Commission Into Aboriginal Deaths In Custody Canberra.

List of cases

Neal v The Queen [1982] 149 CLR 305.

R v Murray, R v Bates [1991] (NSW Court of Criminal Appeal, Unreported, 6 April 1992).

R v Wotton [2007] (Unreported, QDC 181, 25 May 2007).

Prisons and vulnerable persons: institutions and patriarchy

Eileen Baldry, University of New South Wales

1Abstract

The prison has been developing into a mixed mode institution with large numbers of vulnerable persons, including Aboriginal women and people with mental illness and cognitive disability, being serially incarcerated at high rates. The characterisation of prison as a punishing but therapeutic community is bizarre but has its roots in 19th & 20th century patriarchal colonial and welfare institutions, particularly those for women and children. Is prison in the early 21st century the last institution of control left in which to house such vulnerable persons? This paper discusses this development of the prison and its effects.

Introduction

Understanding and explaining the rapid increase in the rate of imprisonment in Australia over the past

two to three decades is occupying a number of criminologists, not least the Australian Prisons Project

group (http://www.app.unsw.edu.au). One aspect of this investigation is exploring why it is that

vulnerable groups of Australians (Indigenous Australians, especially Indigenous women and persons with

mental health disorders and cognitive disability) have developed a much higher risk than previously of

being caught in the imprisonment cycle over this period. This paper opens a new perspective on this

phenomenon by exploring it through the lens of patriarchy and institutionalism.

Background

Between 1998 and 2008 the number of prisoners in Australia increased by 39% and the rate of

imprisonment increased by 20 per cent from 141 to 169 per 100,000 of the adult population with much

of this increase accounted for by the increase in remand (ABS 2008); translating then into higher rates of

sentenced prisoners with around 35% being re-incarcerated in two years and around 70% reincarcerated

at some time in their lives – a cycle of self reproducing higher imprisonment rates. This increase in the

rate demonstrates of course that the prison population is increasing at a significantly faster rate than is

the general Australian population. Census counts mask the number of persons who flow through the

prison system each year. As the majority of prisoners (sentenced and unsentenced) are incarcerated for

less than 12 months, far more than the 27,000 counted on census night flow through the system with

estimates at around 45,000 persons flowing through annually (Baldry et al 2006). The national census

1

also masks significant differences

whereas Victoria’s is 104 (ABS 2008

Australia Imprisonment rates (ABS

The situation for more vulnerable

mental health disorders and cogn

prison population. In this same per

of the prison population to 24 per c

than for the non-Indigenous popula

Ratio of Indigenous to Non-Indigen

ces between states and territories: the Northern Te

008).

(ABS 2008)

able groups, in particular women, Indigenous person

ognitive disability, is markedly worse when compare

period, Indigenous people (male and female) increas

per cent. The rate of imprisonment for Indigenous peo

pulation (age standardized rate) (ABS 2008).

igenous Age Standardised Rates of Imprisonment (AB

Territory’s rate is 610

rsons and persons with

pared with the general

reased from 16 per cent

people is 13 times more

Although the actual number of women prisoners remains small compared to men their proportion has

been increasing. Over this decade (1998-2008) the number of women prisoners increased by 72 per cent

compared with 37 per cent for men, increasing their imprisonment rate from 16 to 24 prisoners per

100,000 adult women (ABS 2008). But incarceration rates for Indigenous women have increased more

rapidly than for Indigenous men and the increase for Indigenous women has been far greater than for

non-Indigenous women. The most recent longitudinal comparison was made in 2006 when the

proportion of Indigenous women prisoners had increased from 21 per cent in 1996 to 30 per cent in 2006

of all women prisoners (ABS 2006). The most recent rate of Indigenous women’s imprisonment available

is 364 per 100,000 of adult Indigenous females compared with 16 for non-Indigenous females (ABS 2008).

The Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner has severely criticized the

over-representation of Aboriginal people and Aboriginal women in particular, in prison (Calma 2005).

Well over a decade ago Cunneen and Kearley (1995:88) had pointed out that the increase in Aboriginal

imprisonment had impacted disproportionately on Aboriginal women.

There is no longitudinal data on rates of persons with mental health disorders (MHD) and cognitive

disability (CD) in prisons in Australia. Mental health disorders include psychosis, affective and anxiety

disorders, and cognitive disability includes those with intellectual disability (ID) (<70 IQ) and with

borderline ID (>70 but <80 IQ). Nevertheless the perception amongst correctional authorities and service

providers is that their numbers and proportions have increased over the past 2 decades (Office of the

Public Advocate 2004; White & Whiteford 2006). Persons with these disabilities are clearly significantly

over-represented amongst prisoners when compared with the general population with rates 3 to 6 times

higher (Butler et al 2006). Persons with CD who have comorbidity (CD and a mental health disorder)

and/or dual diagnosis (CD and alcohol or other drug problem) are even more likely than those with

mental health or cognitive disability alone, to be caught in the imprisonment cycle (Dowse et al 2009;

Hobson & Rose 2008:12). Women with mental health disorders are more highly over-represented

amongst the prison population than men (Butler et al 2003). In NSW the evidence is that overall people

with MHD and CD are convicted and imprisoned for lower level offences such as theft and road

intended to cause injury; and for persons with CD, convictions for alcohol/drug misuse and public order

offences are common (Dowse et al 2009). They also have higher numbers of offences and convictions but

shorter sentences and incarceration periods than persons without these diagnoses and cycle in and out

of prison quickly (Baldry et al 2008b).

In summary the picture for all these groups of people is one of cycling around in a liminal marginalised

and fluid community-criminal justice space (Baldry et al 2006; Baldry et al 2008a). When not in prison,

most are living chaotically, are either homeless or in marginal and poor housing and are under police and

community corrections surveillance resulting in rapid re-arrest; and when they are in prison they are

often in remand or on very short sentences and living in highly structured settings (Baldry et al 2006).

This space is liminal in that it is both in and between the outside community and the longer term prison

sentence setting; it is marginal in that it does not afford access to stable support and services in either

place and in fact promotes serial institutionalisation. It is a combined marginal community and marginal

criminal justice fluid space in which many such vulnerable persons are caught. Peacock (2008) more

recently, has interpreted this space in relation to the net-widening effect of current criminal justice

policies on women, as a ‘third space’, an autonomous space. This interpretation though has not taken

account of the work over the past decade suggesting a different understanding, one in which this space is

not autonomous but is both within and in between community and prison, and is negatively dependent

upon, created and controlled by interaction amongst human service and criminal justice agencies.

Persons cycling in this space are invariably searching for safe structured spaces and support that have

been lacking in their lives (Dowse et al 2009; Baldry et al 2008). Appallingly the prison is often the only

place that provides that (Baldry et al 2006). These persons make up a very large proportion of short term

prisoners and account for a large number of the flow through prisoners discussed earlier.

Explanations for the increase

Various explanations have been posited for the increase in prisoner rates. It has long been recognised

that Australian Indigenous peoples are the subject of racism and have suffered racist treatment in all

spirituality and families, having been stolen as children, having been excluded from education and

employment and having had British laws imposed on them (Cunneen 2009). The Law Reform Commission

of Western Australia (2005) provides an excellent summary of factors contributing to Indigenous

Australians’ over-representation in prisons, including a contextualising and critical examination of higher

offending rates.

Women it is argued have higher use of drugs and have been committing more serious and violent crime

resulting in higher rates of prison sentences than previously but they are also being impacted by harsher

sentencing regimes (Gelb 2003).

Both internationally and in Australia deinstitutionalisation of persons previously held in psychiatric

institutions and the closure of these institutions in favour of treatment and support in the community,

has been blamed for the increase in persons with MHD in prison (Belcher 1988; Aderibigbe 1996;

Harrington 1999). It has been argued for some time that resources to support those with more complex

needs and challenging behaviours have not been transferred to community mental health services, and

that services either are unable or refuse to work with this group leaving them to become homeless,

offend and come to the notice of police (Rose et al 1993).

A large number of policy and legislative changes over the past 20 years have had negative and

disproportionate effects on Indigenous persons, those with MHD and CD and women who are poor,

disadvantaged and racialised (Australian Prison Project 2009; Pratt et al 2005; NSW Legislative Council

Select Committee on Mental Health 2002; NSW Legislative Council Inquiry into the Increase in Prisoner

Population 2001). Policy and legislation has been strongly influenced by the risk aversion approach,

sometimes dubbed ‘actuarial justice’ (Kemshall 2003). Although as O’Malley (2008) points out, risk

management can be used positively such as in a harm minimisation approach, Australian criminal justice

has favoured pre-emptive police attention and incarceration. Such an approach tends to lead to

increased rates of persons held on remand, increased breaching of parole and longer sentences.

Although these explanations illuminate the phenomenon of the growth in the prison population further

deinstitutionalisation, residualisation of the welfare state and the rise of neo-conservatism, provides a

new perspective on vulnerable groups in the criminal justice system.

Patriarchy

Lerner (1986) in her innovative thesis regarding the creation of patriarchy, argued that the initiation of

the subjugation and oppression of women in pre- and early historical times began with the exchange and

ownership of women for their reproductive capacity, through which private property was eventually

created (Lerner 1986:6-10). Over generations this structured ownership of one group by another led to

the development of slavery (of both males and females), class structure (relegating both males and

females to levels on the hierarchical ladder), male god(s) becoming pre-eminent and eventually the

entrenchment of this increasingly sophisticated ideology of patriarchy as the framework in which archaic

states developed and operated (Lerner 1986:36-53). Males gained their class position by their relation to

the means of production and females by their relationship to males. This also was the responsive and

adaptive template for the creation of the ‘western’ state and has been the dominant social and political

paradigm in the west for thousands of years. Lerner argued persuasively from archaeology, early religious

and legal manuscripts and recordings and works by theorists like Levi-Strauss, Meillassoux and Engels to

support her theory. She also argued that patriarchy has been and is the dominant social, economic and

political paradigm maintaining itself by adaptive transformation and spawning a range of successful

supporting ideologies and frameworks.

Most relevant to the matter at hand, an implication of Lerner’s theorising is that colonialism was not just

tightly affiliated with patriarchy, but that it was (as evidenced in ancient empires) and is an economic &

political manifestation of patriarchy. This opens up a broader field in which to explore vulnerable groups

in the criminal justice system in Australia.

Colonisation

This patriarchal-colonial paradigm was transported, along with the convicts, to Australia by the invading

British in 1788. Indigenous Australians were subjected to this new social, economic and political structure

variously murdered because they stood in the way of colonial acquisition, herded onto missions as

irrelevant to the colonising project and so expendable, or relegated to the lowest servant class as useful

workers. Indigenous women suffered in these and other ways with their sexuality commodified via rape

and sexual servitude (Chesterman & Galligan 1997).

Payne (1992) argued that Aboriginal women’s relationship to western law

was founded in Australia’s colonialism in which patriarchal colonial culture dismissed Aboriginal

women’s high status and assumed that in Aboriginal society women were subordinated in the same

way that they were in British society (Payne 1992:68).

She pointed out that this attitude continued into the current era with the dismissive approach to the

large number of Aboriginal women being murdered in the Northern Territory (in domestic violence

contexts) whilst the Aboriginal Deaths in Custody Royal Commission was investigating a similar number of

Aboriginal men’s deaths in custody (Payne 1992:68).

Further evidence of the patriarchal nature of colonialism and its impact is given by Cunneen and Kearley

(1995) who use the intersecting ideologies of class, race and gender in their analysis of the experience of

Indigenous Australian women in the criminal justice system. They argue that these ideologies continue

the process of colonisation in which the class position of Aboriginal peoples in Australia is related directly

to colonial dispossession (Cunneen & Kearley 1995:73). The policies of reducing the Aboriginal birth rate

and controlling the sexuality of Aboriginal and ‘part-Aboriginal’ young women and girls by removing and

institutionalising them (p74) exemplified ‘the social and spatial positioning of Aboriginal females (as)

indicative of dominant power relations’ (Cunneen & Kearley 1995:79).

Police treatment of Aboriginal women more starkly reveals the continuing patriarchal-colonial attitude of

the criminal justice system. Cunneen (2001) exposes the extraordinarily high rates of Indigenous Australia

women taken into police custody: they comprise 50% of all women taken into custody and are 58 times

more likely to be detained than non-Indigenous women, significantly higher than the comparable figure

Institutional Control: old institutions

One means by which patriarchy is maintained is through institutions. Institutional systems, both formal,

such as the prison, the British law, the military, the church, the orphanage and the mission and informal

such as the nuclear male headed family and the British class system, were part of the colonising package

that the British brought with them to New South Wales and were imposed upon Indigenous peoples

(Baldry & Green 2003).

Institutions in the form of missions, reserves, religious and state boys’, girls’ and women’s ‘homes’ were

created as one means to control Indigenous Australians. Indigenous females were trained as domestic

servants or were controlled on missions and in work houses or reformatories. State institutions, asylums,

also were developed during the 19th and 20th centuries to control and care for the mentally ill and

intellectually disabled.

Nowhere provides a better example of patriarchal-colonial state control of females via institutional

means and the conflation of classism, racism and sexism than the Parramatta Female Factory and Girls

Home in NSW (Parragirls 2009). It began in the first decades of the colony as a welfare institute for

convict women and their children; quickly became the Parramatta Female Factory where convict women

were incarcerated and required to work (similar institutions were built around the country) but were also

subjected to almost constant rape; morphed into a Lunatic asylum in 1848 and incarcerated women over

its 130 years, a large number of them Indigenous (see Haskins 2001 regarding declaring Aboriginal

women insane in order to institutionalise and control them). Next door to the Female Factory an

orphanage was built in 1841 in which girls, many of them stolen Aboriginal children, were raised in

punishing circumstances by the Catholic Church. In 1887 the orphanage became an Industrial School for

Girls (a euphemism for a girls’ detention centre) later known as the Parramatta Girls Home, only to be

taken over in 1980 by the Department of Corrective services as a women’s prison. This one geographical

location and institution with its many manifestations, exemplifies the various institutional forms used to

control Indigenous, poor, disadvantaged women and those with mental and cognitive disability and

Deinstitutionalisation & residualisation of welfare

The 1960s and 70s saw progressive Human Rights, humanitarian, de-colonisation and self-determinist

challenges to the values represented in these old institutions.

The Civil Rights movement in Australia during the 1950s and 60s culminated in the referendum in 1967

that overwhelmingly approved changes to the Australian Constitution confirming full civil rights for

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. The ten years following the referendum saw the

abolition of Aboriginal Welfare Boards and the closure or handing over to Indigenous communities of the

many dozens of missions and institutions across the country, for example the Cootamundra Girls Home,

that had confined and detained them for decades (National Museum of Australia 2008).

The same period (1960s – 1980s) saw the process of the deinstitutionalisation of long term psychiatric

patients gain pace along with the closure of psychiatric institutions and later of institutions for those with

intellectual disability in Australia. This saw the number of psychiatric hospital beds decrease from 281 per

100,000 in the 1960s to 40 per 100,000 in the 1990s (Petersen et al 2002:122) but without the

concomitant support, particularly for the most vulnerable of these persons – Indigenous peoples, the

poor and homeless – established in the community.

This may be partly explained by the perverse alignment, during the late 1970s through the 90s, of

economic rationalism with these institutional closures. A period of decline in welfare support, in fact a

residualisation of welfare and a hollowing out of the state, reduced in real terms access to public goods

such public housing, education, mental health care, disability and unemployment benefits for the most

marginalised (Mendes 2008).

So by the 1990s the formal colonial institutions that had confined and controlled Indigenous Australians,

especially Indigenous women, had gone. The formal (such as segregated and streamed school education;

and lack of divorce options) and informal (such as the family structure; and re-domestication of women

after WWII) institutional means by which not only women but all in the lower classes, had been kept

under control, were diminishing or were being challenged. The institutions that had controlled those with

Fightback: Reasserting (subtler) patriarchal control

During the 1980s, 90s and early 21st century there has been a struggle to deal with the loss of these

institutions that previously maintained these groups of people ‘in their place’ in the class hierarchy and

controlled their behaviour. At the same time these persons, both individually and as members of groups,

seek safe, secure and structured places in which to live but rarely find them (Baldry et al 2006).

So persons who were once controlled by the old institutions are no longer controlled in this way; and ‘the

community’, its organizations and supports, portrayed as the solution, have failed to provide, for

whatever reason, the level support (and control) required (Bryson & Mowbray 1981). Communities and

social services on the whole have been unable and/or unwilling to accommodate persons with highly

complex needs because such agencies are funded to be successful with their clients. These ‘clients’ are

not those who display the successful outcomes required by government and other funding bodies and so

are often excluded; they require long term support whereas many community programs are funded for

short term support programs.

How then to manage this problem; these groups of people who were, hitherto able to be controlled? As

Lerner demonstrated, colonial patriarchy is like a virus: it is pervasive, aggressive and highly adaptable.

Most people in a society do not recognise they are living within this paradigm or that almost everything

in the society is geared to support it – hence the need for de-colonisation. Responses to this loss of old

institutions, whether conscious or unconscious, by design or by default have been to re-assert control via

reconfiguring the institutions that are left.

Social housing and the criminal justice system, especially the prison, are virtually the last major formal

institutions left in Australia and are being, at least on the surface, remade as multi-mode ‘therapeutic’

agencies to house, control and ‘treat’ marginalised and criminalized persons. Social Housing, public

housing in particular, is now an institutional setting for Indigenous Australians and for increasing numbers

of persons with mental illness and those being released from prison; police have been re-positioned as

the frontline CJS-therapeutic agents; prison, as the pointy end of the criminal justice system, is now the

multiple co-occurring disorders and disability who have no safe community space such as a family home

or a secure long-term therapeutic setting. Colonial patriarchy has re-organised its institutions but this is

no simple reassertion of control. Challenge to and struggle over these sites of management and control

continues.

An analysis such as this suggests the need to move into a post-Foucault theorising phase: Foucauldian

analysis, galvanizing though it has been in its illumination of the nature of institutions and control, did not

address the patriarchal paradigm discussed here. Not surprisingly this new circumstance requires a

refreshed approach to the reinvented institutions of the 21st century.

Conclusion: Re-positioning the institution

When brought together, all these elements: Lerner’s theory (patriarchal-colonialism), the rise of

neo-conservative ideology, the residualisation of welfare and deinstitutionalisation, provide a new

perspective on the nature and development of the Australian jurisdictions’ criminal justice systems and

their increasing rate of imprisonment of vulnerable groups.

This critical analysis suggests that public/social housing and the criminal justice system, especially prisons,

have become the last institutions in Australian society in which to control & accommodate Indigenous

women and those with serious disadvantage, co-morbidity and dual diagnosis who have no safe place for

healing, housing or care. The prison in particular has been repositioned to do this via legislation, policy

and the witting or unwitting compliance of human service and criminal justice bureaucracies and

agencies. The reconfigured prison of the early 21st century is indeed a manifestation of adaptive

patriarchal colonialism.

References

ABS [Australian Bureau of Statistics] 2006 Prisoners in Australia ABS Canberra. ABS [Australian Bureau of Statistics] 2008 Prisoners in Australia ABS Canberra.

Aderibigbe Y 1996 ‘Deinstitutionalisation and Criminalization: tinkering in the interstices’ Forensic Science International vol 85 pp127-134.

Australia Prison Project 2009 http://www.app.unsw.edu.au.

Baldry E Dowse L Snoyman P Clarence M & Webster I 2008a 'A critical perspective on Mental Health Disorders and Cognitive Disability in the Criminal Justice System' in C Cunneen & M Salter (Eds) Proceedings of the 2008 Critical Criminology Conference UNSW Sydney.

Baldry E Dowse L Snoyman P Clarence M & Webster I 2008b 'Reconceptualising disability in the criminal justice system: People with mental health disorders and cognitive disability' Paper presented at ANZSOC Annual Conference Canberra 26-28th November.

Baldry E McDonnell D Maplestone P & Peeters M 2006 'Ex-prisoners, Homelessness and the State in Australia'

The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology vol 39 no 1 pp 20-33.

Baldry E Ruddock J & Taylor J 2008 Aboriginal women with dependent children leaving prison project: needs analysis report Homelessness NSW Sydney.

Belcher J 1988 'Are Jails Replacing the Mental Health System for the Homeless Mentally Ill?' Community Mental Health Journal vol 24 no 3 pp 185-195.

Bryson L & Mowbray M 1981 'Community: the spray on solution' Australian Journal of Social Issues vol 16 no 4 pp 255–267.

Butler T Andrews G & Allnutt S 2006 'Mental disorders in Australian prisoners: a comparison with a community sample' Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry vol 40 pp 272-276 Calma T 2005 Social Justice Report 2005 Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Sydney. Chesterman J & Galligan B 1997 Citizens without Rights Aborigines and Australia citizenship Cambridge

University Press Cambridge.

Cunneen C and Kearley K 1995 Indigenous Women and Criminal Justice: some comments on the Australian situation in K. Hazelhurst (ed) Perceptions of Justice Aldershot England Aveburypp71-94. Cunneen C 2001 Conflicts, Politics and crime: Aboriginal communities and the police Allen & Unwin Crows Nest Cunneen C 2009 'Criminology, criminal justice and Indigenous people: a dysfunctional relationship?' Current

Issues in Criminal Justice vol 20 no 3 pp 323-336.

Dowse L Baldry E Snoyman P 2009 Disabling criminology: conceptualizing the intersections of critical disability studies and critical criminology for people with mental health and cognitive disabilities in the criminal justice system Australian Journal of Human Rights vol 15 no1 (in press).

Gelb K 2003 'Women in prison: why is the rate of incarceration increasing?' Evaluation inCrime and Justice: Trends and Methods Conference Australian Institute of Criminology Canberra 24-25 March Harrington S 1999 New Bedlam: Jails -- Not Psychiatric Hospitals -- Now Care for the Indigent Mentally Ill The

Humanist vol 59 no 3 pp 9-10.

Haskins V 2001 On the Doorstep: Aboriginal domestic service as a contact zone Australian Feminist Studies vol 16 no 34 pp 13-25.

Hobson B & Rose JL 2008 The Mental Health of People with Intellectual Disabilities who Offend The Open Criminology Journal vol 1 pp 12-18.

Kemshall H 2003 Understanding Risk in Criminal Justice Open University Press Berkshire.

Law Reform Commission of Western Australia 2005 Aboriginal Customary Laws Project 94 Discussion Paper LRCWA Perth.

Lerner G 1986 The Creation of Patriarchy New York Oxford University Press.

Mendes P 2008 Australia's Welfare Wars Revisited: The Players, the Politics and the Ideologies UNSW Press Sydney.

NSW Legislative Council Inquiry into the Increase in Prisoner Population 2001 Inquiry into the Increase in NSW Prisoner Population Final Report NSW Parliament Sydney.

NSW Legislative Council Select Committee on Mental Health 2002 Final Report NSW Parliament Sydney. Office of the Public Advocate Victoria 2004 Submission to HREOC's review of mental illness and human rights

Online: http://www.publicadvocate.vic.gov.au/Research/Submissions/-HREOC-and-MHCA-Mental-Health-and-Human-Rights-submission.html.

O'Malley P 2008 'Experiments in Risk and Criminal Justice' Theoretical Criminology vol 12 no 4 pp 451-469. Parragirls (2009) http://www.parragirls.org.au/ (last accessed December 2009).

Payne S 1992 'Aboriginal women and the law' in C. Cunneen (Ed) Aboriginal Perspectives on Criminal Justice

Monograph Series No 1 Sydney University Institute of Criminology Sydney.

Peacock M 2008 'A third space between the prison and the community: post-release programs and re-integration' Current Issues in Criminal Justice vol 20 no 2 pp 307-312.

Petersen A Kokanovic R and Hansen S 2002 Consumerism and health care in a culturally diverse society in S Henderson & A Petersen (Eds) Consuming Health: the commodification of health care Routledge London pp 121-139.

Pratt J Brown D Brown M Hallsworth S & Morrison W (Eds) 2005 The New Punitiveness: Trends, theories, perspectives Willan Press Devon.

Richmond Report 1983 Inquiry into Health Services for the Psychiatrically Ill and Developmentally Disabled (N.S.W.) Department of Health NSW Sydney.

Rose S Burdekin B and Jenkin R 1993 Human rights & mental illness: report of the National Inquiry into the Human Rights of People with Mental Illness HREOC Sydney.

Mainstreaming problem-oriented justice: issues and challenges

Lorana Bartels, Criminology Rresearch Council

1Abstract

This paper grapples with the challenges of introducing features of specialty courts into the mainstream criminal justice system. Specialty courts were first introduced in Australia in the late 1990s, in recognition of the fact that the social problems which may have contributed to an offender’s behaviour may require social, rather than legal, solutions. There are currently a number of specialty court and diversion programs in place in Australia. In most cases, however, these programs only deal with a small minority of offenders. In particular, specialty court programs such as resource-intensive drug courts tend to be focused in metropolitan areas and access is therefore restricted to urban offenders. Regional and rural offenders may face further disadvantage due to the comparative lack of appropriate services provided locally. Mainstreaming aspects of specialty court programs may promote more equal access to court innovations for a greater proportion of offenders. This paper examines three challenges associated with attempts at mainstreaming, namely: promoting equity, resource issues and the role of the judicial officer. Generic court intervention programs, such as the Victorian Court Integrated Services Program, will be considered, and the need for cohesive policies on the future of problem-oriented justice examined.

Introduction

Specialty courts were first introduced in Australia in the late 1990s in recognition of the fact that social

problems which have contributed to a defendant’s behaviour may require social solutions (Freiberg 2001).

It has been suggested that problem-oriented courts ‘challenge the nature of courts and represent

something of a revolution in the way in which courts might operate in modern, democratic societies’

(Phelan 2003:99). Problem-oriented courts act as a ‘hub’ to connect various ‘spokes’, eg alcohol and drug

treatment, community corrections and domestic violence agencies, forming a holistic and integrated

approach (Blagg 2008). The processes by which these courts operate and the outcomes they seek to

achieve vary significantly from program to program, making it difficult to identify common elements and

define their structures (Payne 2006:2). However, the key features of problem-oriented justice, whether in

specialty courts or the mainstream criminal justice system, are: focus on case outcomes; system change;

judicial monitoring; collaboration and non-traditional roles (Berman & Feinblatt 2001; Payne 2006; King

et al 2009).

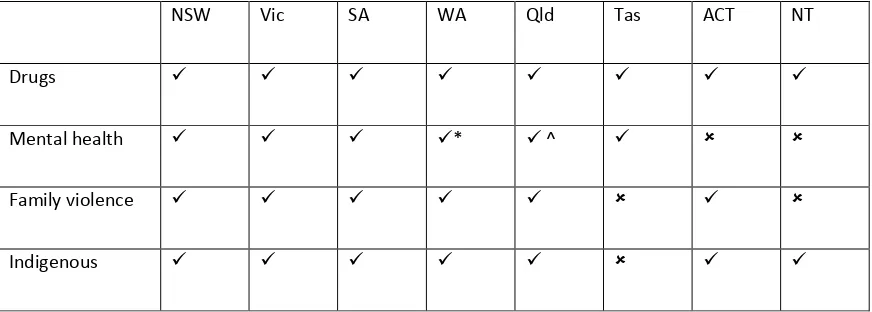

There are currently a number of specialist courts, lists, approaches and court support services in place in

Australia, especially in the context of drug/alcohol dependence; mental health; family violence and

Indigenous defendants (see Table 1; King et al 2009:142-158, 178-183). In most cases, however, these

programs only deal with a small minority of defendants, especially in metropolitan areas. Regional and

1

rural defendants may face further disadvantage due to the comparative lack of appropriate services

provided locally. It is not practical or, in some instances, necessary to introduce specialty courts wherever

a traditional court currently operates. Furthermore, existing specialty courts tend to focus on a specific

issue, such as mental health, and may not address all of an offender’s relevant issues. One means of

enhancing social justice outcomes may be to introduce problem-oriented justice approaches which seek

to address these issues in a comprehensive and holistic way into the mainstream criminal justice system.

Mainstreaming principles of problem-oriented justice or specific practices may promote more equal

access to court innovations for a greater proportion of defendants (Gray 2008). It may also enable better

coordination of services and ensure that the level of intervention is more appropriately tailored to the

level of need and risk. It is not suggested that such programs would be a substitute for existing specialty

courts, but that they would serve to complement them.

This paper discusses some of the issues associated with bringing aspects of problem-oriented justice into

the mainstream criminal justice system and examines three challenges, namely: promoting equity,

resource issues and the role of the judicial officer. This paper is based on work undertaken on behalf of

the Criminology Research Council [CRC] (Bartels 2009). In June 2009, the CRC organised a roundtable on

these issues and this paper draws on some of the discussion themes at the roundtable.

Table 1: Key specialty/problem-oriented courts and programs in Australia2

NSW Vic SA WA Qld Tas ACT NT

Drugs

Mental health * ^

Family violence

Indigenous

* only intellectual disability; ^ not sentencing.

2