PEER-REVIEWED PAPER

P

ARTNERING

M

EASURES

By Travis G. Crane,1

Jennifer P. Felder,2

Paul J. Thompson,3

Matthew G. Thompson,4 and Steve R. Sanders,5

Associate Member, ASCE

ABSTRACT: Although many articles have been written about the use of partnering in the engineering and construction industries in recent years, none have addressed the subject of partnering measurement. Recent research has now made it possible for information on part-nering measures to be added to the existing body of partpart-nering literature. Measures allow participants to assess the current status of the partnering arrangement and identify strengths and weaknesses. However, the measures used in a partnering relationship will not be effective unless they are developed in the proper manner. Measures must reflect parameters that are indicative of goal achievement. Additionally, partnering measures must be tailored to suit the culture, needs, and abilities of all involved parties. Because monitoring requires resources, it is best to strategically select a system that measures only those aspects of the partnering relationship most critical to success. This article discusses the use of measures at various levels of the partnering relationship — the alliance, project, and discipline levels. It also out-lines three different types of measures — results, process, and relationship. The important thing for an organization to remember is that the various types and levels of measures combine to form an information system useful in evaluating the partnering relationship.

INTRODUCTION

Many articles have been published recently describing the partnering process. However, none of these articles have focused on the importance of establishing measures to help manage a partnering relationship. Research has been conducted with the objective of identifying and de-veloping a set of measures to manage the partnering pro-cess and gauge progress toward established goals (San-ders et al. 1996). The writers surveyed companies engaged in either long-term strategic alliances or project-specific relationships to identify differing approaches to partnering, the underlying reasons for choosing a specific approach, and results achieved. Of the companies sur-veyed, 21 successful partnering relationships were se-lected for detailed interviews. These interviews were

1Proj. Engr., Kokofing Constr. Co., 886 McKinley Ave., Columbus,

OH 43222.

2Proj. Administrator, Lockwood Greene Engrs. Inc., P.O. Box 491,

Spartanburg, SC 29304.

3Grad. Student, Dept. of Civ. Engrg., Clemson Univ., 133 Lowry

Hall, Clemson, SC 29634-0911.

4

Grad. Student, Dept. of Civ. Engrg., Clemson Univ., 133 Lowry Hall, Clemson, SC.

5

Assoc. Prof., Dept. of Civ. Engrg., Clemson Univ., 200 Lowry Hall, Clemson, SC.

Note. Discussion open until September 1, 1999. To extend the clos-ing date one month, a written request must be filed with the ASCE Manager of Journals. The manuscript for this paper was submitted for review and possible publication on September 18, 1997. This paper is part of the Journal of Management in Engineering, Vol. 15, No. 2, March/April, 1999. qASCE, ISSN 0742-597X/99/0002-0037 – 0042/$8.001$.50 per page. Paper No. 16611.

conducted with two primary objectives in mind — to identify benchmarks achieved through partnering and to evaluate key success factors leading up to such accom-plishment. Furthermore, in support of these objectives, this research uncovered that organizations in successful partnering relationships commonly developed a system to assess the current ‘‘health’’ of the relationship and monitor progress toward goal achievement.

The topic of partnering has been researched exten-sively in recent years (Sanders et al. 1996; CII 1991; Schmader 1994; Weston and Gibson 1993; Abudayyeh 1994; Brown 1993). However, the focus of this article is on providing a summary of the different measures in use on partnered projects and the procedures followed in the development of such measurement systems. Some examples of these measurement systems are provided as well.

PROCESS FOR DEVELOPING MEASURES

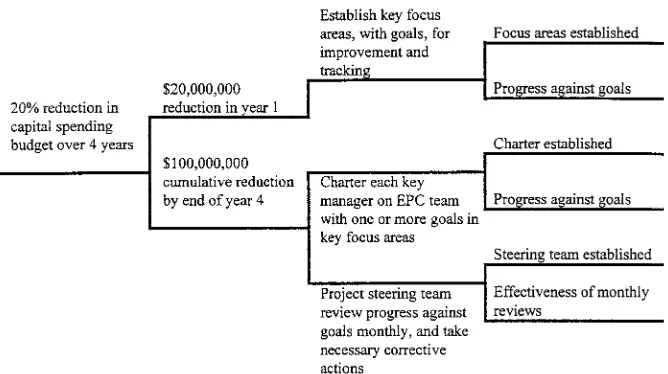

FIG. 1. Objectives, Goals, Strategies, and Measures Branch

focus on milestones — monitoring progress toward the desired end result.

To achieve partnering objectives, organizations de-velop strategies. Measures must be closely tied to the execution of these strategies and should be chosen for their effectiveness in providing an accurate reflection of progress toward established goals. Such measures assist with providing continuity throughout the partnering pro-cess, ensuring that separate pursuits combine to support the overall effort or plan. Measures that accurately rep-resent progress toward the accomplishment of business objectives do so because they were developed in a log-ical, top-down manner, with business results as the driv-ing focus.

One company experienced in partnering shared a pro-cess called ‘‘Objectives, Goals, Strategies, Measures’’ (OGSM) to aid in the development of measures. The first step in working through this process is to identify overall company objectives or business drivers. Second, inter-mediate goals are identified to support the achievement of the objectives. Third, strategies are developed to di-rect efforts toward goal achievement. Fourth, measures are created to assess progress toward effective imple-mentation of strategies. Fig. 1 is an example of one of the OGSM branches developed by the company. Be-cause the process works from general to specific, mea-sures are developed to support the partnering objective. This process of clearly identifying goals, designing ap-propriate strategies, and monitoring progress according to a set of measures provides a framework for

• Establishing and communicating goals • Monitoring progress

• Evaluating results

This process allows participants to focus their efforts on items of highest priority — those most significantly af-fecting project results.

The development of an effective monitoring process typically follows a period of discussion among individ-uals representing the interests of each partner, including

various levels within each partner company. When af-fected parties participate in plan development, ‘‘buy in’’ to the final plan is more easily achieved. Additionally, through consultation with individuals familiar with spe-cific work processes or activities, proper measurement of the most significant project aspects will most likely result. In the absence of employee representation, em-ployees may suspect that measures developed are not equitable — intended to benefit one party more than an-other.

An effective measurement system must contain two basic elements: a performance baseline and a means for determining actual values. Using an example from the OGSM process, a goal for a company may be to reduce engineering costs by 5% for each of the next four years. In order to assess progress toward the achievement of this goal, some information must be gathered regarding the baseline of current engineering costs. To determine actual values, the partners would monitor engineering costs on an ongoing basis. Comparison of the historical baseline with current engineering costs would allow the partnering relationship to assess its progress toward goal achievement. Data collection procedures must be well defined to ensure consistency among data and to provide for valid comparisons between the baseline and actual values.

TYPES OF MEASURES

It is important to remember that measures are useful beyond a simple reporting function. Reporting is data, and what the decision-maker needs is information (Bo-sakowski 1993). Measures should provide for a proactive method of control. It is not enough for the partners to know that an activity is behind schedule. They have to know what caused the delay, the impacts of the delay, and what options exist for getting the project back on schedule. When critical areas are monitored continually, partners immediately recognize when problems occur and can make timely and effective corrections. In the absence of such measures, progress toward completion becomes ill-defined, and critical delays may not be rec-ognized in a timely fashion. Three different types of measures — result, process, and relationship — are used to ensure that appropriate information is available at the right time.

Result measures are ‘‘hard’’ measures based on per-formance. Companies that were interviewed all used cost, schedule, quality, and safety as result measures. Cost and schedule variance can be used to measure how well the project adheres to the original estimate and schedule. Quality typically includes such measures as the amount of rework required. Safety can be measured by compiling safety statistics such as lost time incidents.

Measures can be used for strategic adjustments, mid-course corrections, or continuous improvement. Each type of measure has a specific use and preferred appli-cation. Result measures are most useful for making stra-tegic adjustments to the partnering relationship. How-ever, since result measures typically rely on activity completion, they are of limited value for making mid-course corrections. The partnering relationship must turn to another type of measure to assess progress toward goal accomplishment in these areas.

Process measures are used to effectively track in-progress activities, and thus provide an early-warning system for identifying necessary midcourse corrections. Trouble areas discovered with process measures can be corrected or adjusted in a timely manner. The primary advantage of identifying potential problems early is to provide the decision-maker with the greatest number of options for problem solution. Corrections made early tend to result in reduced project expenses and improved partner relations. Following is a list of some commonly used result and process measures:

1. cost

• Cost performance index • Project within cash flow plan • Billable ratio (engineering)

• Engineering work-hour/unit of product

• Third-party work sampling to determine contrac-tor effectiveness

• Value engineering savings

• Engineering as a percentage of total installed cost • Duplication of effort

• Cost growth

• Overhead as a percentage of total installed cost 2. schedule

• Schedule performance index • Milestones met

• Immediate notification of delays

• Preassembly of equipment (percentage of total) • Timely issue of engineering documents and

equipment

• Availability of spare parts/change parts • Cycle time (product to market)

• Time to process change orders, purchase orders, requests for information, etc.

3. safety

• Lost-time and non-lost-time incidents

• Occupational Safety and Health Administration recordable incidents

• Drug testing results

• Safety training performed on time • Same-day correction of safety problems 4. quality

• Conformance to specifications • Achievement of operating objectives • Percent of rework

• Plant output

• Participation in design by construction/manufac-turing personnel

• Start-up performance

• Number of engineering changes • Customer feed back

• Audit deviations • Errors and omissions • First pass yield 5. litigation

• Outstanding claims

• Number of conflicts elevated to each level

Fig. 2 is an example of a set of process measures that provide a cumulative measurement system to track the achievement of goals in process. These measures should be keyed to the critical factors affecting the successful completion of the project and should be tied to the goals of the partnering relationship.

Just as results measures are inadequate for some pur-poses, process measures also have their shortcomings. Process measures are concerned with the short-term, im-mediate impacts of problems in the process; they tell the decision-maker little or nothing about the condition of the environment in which the process is taking place. To obtain this kind of information, a partnering relationship must make use of relationship measures to achieve a greater degree of foresight and realize the benefits of increased time to react to problems in the relationship.

Relationship measures are often referred to as ‘‘soft’’ measures, and are used to track the activities and effec-tiveness of the partnering team. Following is a list of some sample relationship measures:

FIG. 2. Objective Performance Rating Based on Process Measures

FIG. 3. Sample Performance Profile

• Worker morale • Internal trust/candor • External trust/candor • Internal leadership • External leadership

• Accomplishment of objectives • Utilization of resources • Problem solving • Creativity and synergy

• Timely evaluation and appropriate response

• Definition and adherence to roles and responsibil-ities

• Continuous improvement

• Teamwork

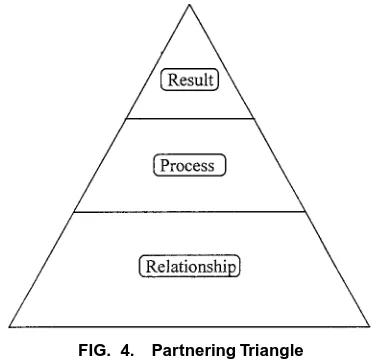

FIG. 4. Partnering Triangle

effectiveness of the partnering relationship. It is impor-tant that these measures reflect the goals that were iden-tified at the outset of the relationship. Fig. 3 is an ex-ample of a survey one company used to measure the performance of its partnering relationship.

Relationship measures are critical because the percep-tion of partnering by participants often will influence attitudes toward partnering. Attitudes — positive or neg-ative — are great predictors of the future success of the relationship. If employees perceive partnering as a good idea with high potential for increasing efficiency, creat-ing a better work environment, and reduccreat-ing costs, they will be likely to make an exceptional effort to advance the relationship. Otherwise, if partnering is not seen as an asset by employees, their commitment to it can be half-hearted, and this negative perception can result in a self-fulfilling prophecy. Relationship measures can iden-tify these attitudes early in the process and warn that the relationship is not what it should be.

When making decisions based on relationship mea-sures and process meamea-sures, it is important that the de-cision-makers look at trends, not individual data points. Relationship measures monitor processes and ongoing activities to assess levels of cooperation and trust, and individual data points do not portray this information.

LEVELS OF MEASURES

In addition to making a distinction between the dif-ferent types of measures, a partnering relationship also has to recognize the different levels at which measures may be applied. Measures may be established at the re-lationship, project, and discipline levels. Just as a certain type of measure is appropriate for a certain situation, the value of the information derived from a measure is di-rectly related to the appropriateness of the level to which it is applied.

Alliance measures track performance at the manage-ment level across multiple projects. Project measures monitor the accomplishment of key criteria for a specific project. Discipline measures apply to the impact of part-nering at the lowest levels of a project. The interviews revealed many combinations of alliance, project, and dis-cipline measures, with most companies using a combi-nation of measures to track the progress of the

relation-ship. One alliance implemented measures only at the alliance level, assuming that if the relationship is ‘‘healthy,’’ the individual projects will proceed without any problems. Other partnering organizations imple-mented extensive measures solely at the project level. One company used only discipline measures. All were successful measurement systems, because each was ap-propriately keyed to the culture and objectives of the particular relationship.

It is important to remember that all three levels of measures are important in their proper place, and that the combination of measures used must always be tied to the partnering culture and objectives. For some ob-jectives, measures at a certain level may be of little use, while another level may provide valuable information. The various types and levels of measures work together as an information system, not as individual tools, and should be combined to form a useful and cohesive whole.

Fig. 4 depicts this relationship between the three pri-mary types of measures — result, process, and relation-ship. Relationship measures assess the ‘‘health’’ of the partnering team, focusing on the interactions and inten-tions of team members. If the partnering relainten-tionship is healthy, with cooperation and collaboration dominating interactions, a solid foundation is in place for processes to be developed in support of the relationship. Process measures focus on the effectiveness of systems in use, assessing progress toward goal achievement. If progress is according to schedule, the second-level foundation is in place for results to be achieved, validating the choice to partner. Desirable results are dependent on effective processes. Effective processes are dependent on healthy relationships.

Relationships, process, and result measures combine to form a ‘‘viewing window’’ into the partnering rela-tionship. Each separate measure serves as a means for uncovering an aspect of partnering critical to success. Taken together, these separate measures form an infor-mation system providing participants with a clear view of the partnering mechanism.

CONCLUSIONS

The establishment of measures is an important aspect of the partnering process. If they are created properly, measures will provide valuable information about the performance of a partnering relationship. They can help managers determine the effectiveness of the relationship and of the various processes so that appropriate actions may be taken to ensure the realization of established goals. Overall, measures can contribute to partnering success through alerting the participants to strengths and weaknesses within a partnering relationship.

objectives. It is imperative that the measures used by a partnering relationship be linked to established goals. To be most efficient and effective in the measurement pro-cess, factors must be prioritized and attention directed to only the most significant items. When insignificant or irrelevant items are measured, resources are wasted, and frustration with such activities can affect overall morale. Measures have to provide trend information, not data, because the value of a measure lies in its potential as a decision-making tool. Finally, the organizations need to determine which types of measures are best suited to their needs, as a result, process, and relationship mea-sures each relate to separate objectives.

An effective measurement system consists of mea-sures reflective of goal accomplishment, and eliminates items providing little added benefit to the partners. An effective measurement system is designed to measure in proper time intervals, retrieving information as needed without burdening participants unnecessarily. An

effec-tive measurement system defines the roles of

participants — who will be required to monitor and re-trieve results. Finally, an effective measurement system incorporates the final function of use — how retrieved data will be combined to form a system informing par-ticipants regarding the current health of the relationship

and performance of the partnering team. The develop-ment of good measures may take considerable effort, but once developed, measures provide an effective means of monitoring and controlling the partnering relationship.

APPENDIX. REFERENCES

Abudayyeh, O. (1994). ‘‘Partnering: A team building approach to quality construction management.’’ J. Mgmt. Engrg., ASCE, 10(6), 26 – 29.

Bosakowski, P. (1993). ‘‘Data and information . . . is there a differ-ence?’’ 1993 PMI Proc., Project Management Institute, Newtown Square, Pa., 322 – 326.

Brassard, M. (1989). The memory jogger plus1. GOAL/QPC, Me-thuen, Mass.

Brown, J. H. (1993). ‘‘Partnering on engineering/construction E/C projects.’’ PM Network, Newtown Square, Pa., Dec.

Construction Industry Institute (CII). (1991). ‘‘In search of partnering excellence.’’ CII Publ. 17-1, University of Texas at Austin, Tex., July.

Sanders, S. R., Thompson, P. J., and Crane, T. G. (1996). The part-nering process — its benefits, implementation and measurement. Construction Industry Institute, University of Texas at Austin, Tex. Schmader, K. J. (1994). ‘‘Partnered project performance in the U.S. Naval Facilities Engineering Command,’’ thesis, University of Texas at Austin, Tex.