Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:30

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Information Literacy and Office Tool

Competencies: A Benchmark Study

John H. Heinrichs & Jeen-Su Lim

To cite this article: John H. Heinrichs & Jeen-Su Lim (2009) Information Literacy and Office Tool Competencies: A Benchmark Study, Journal of Education for Business, 85:3, 153-164, DOI: 10.1080/08832320903252371

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320903252371

Published online: 08 Jul 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 89

View related articles

CopyrightC Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0883-2323

DOI: 10.1080/08832320903252371

Information Literacy and Office Tool Competencies:

A Benchmark Study

John H. Heinrichs

Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, USA

Jeen-Su Lim

University of Toledo, Toledo, Ohio, USA

Present information science literature recognizes the importance of information technology to achieve information literacy. The authors report the results of a benchmarking student survey regarding perceived functional skills and competencies in word-processing and presentation tools. They used analysis of variance and regression analysis to analyze the mean differences between two information domains and the determinants of perceived and desired competencies. The study supports previous research findings that highlight the need to infuse software-application productivity tools and the collaboration competency into the higher education academic curriculum to enhance information literacy. Practical implications and research directions are discussed.

Keywords: Benchmarking, Certification, Information literacy, Office tools, Productivity tools

The present competitive environment is focused on a knowledge-based economy. In this knowledge-based econ-omy, the work required for success demands information literacy and technical skills proficiency of the organization’s workers (Desplaces, Beauyais, & Peckham, 2003). To meet this demand, higher education academic programs are in-creasingly teaching the information and technology skills associated with word processing and presentations in sup-port of the required components of information literacy (Grafstein, 2007). As a result, future employers can expect interviewing students to be information literate, possess tech-nical skills, and possess critical analytical capabilities (Mc-Donald, 2004).

The present information science literature identifies and emphasizes the importance of information technology skills as the basic requirements for information literacy (Burkhardt, 2007; Grafstein, 2007). The knowledge gained and learning experience obtained from working with various collabora-tion, word-processing, and presentation tools provide impor-tant information technology skills that are part of many uni-versities’ information literacy programs (Pask & Saunders,

Correspondence should be addressed to John H. Heinrichs, Wayne State University, Library and Information Science, 106 Kresge Library, Detroit, MI 48202, USA. E-mail: ai2824@wayne.edu

2004). According to Pask and Saunders, information literacy and computer skills can be considered as a composite mea-sure consisting of five core skills: basic computer, advanced computer, internet, research, and presentation.

In this knowledge-based economy, every organizational member must generate, critically analyze, and disseminate knowledge and ideas to support effective knowledge shar-ing. Phillips (2001) argued that the identified core technical skills should include sharing data and documents as well as collaborating in virtual workgroups. Yet, the methods for sharing information and knowledge have changed dramat-ically with the introduction of Web portals, wikis, blogs, and instant messaging capabilities. These new collaboration tools require different types of skills and competencies, such as instant message creation and typing; organizing text, au-dio, and video in the Web environment; research skills using tools such as Google and Wikipedia; and sharing knowl-edge through the use of blogs, wikis, and other community knowledge-sharing tools (Boulos & Wheeler, 2007).

Davis (2003) reported that present and future function-alities in software productivity tools used by the organiza-tion’s knowledge workers are altering the very nature of the work performed in the organization. Adkins and Esser (2004) stated that organizations are seeking candidates who can con-tribute and perform effectively in an increasingly technology-based work environment. McDonald (2004) stated that there

is a perspective among hiring managers that training and worker competency in technology-based software produc-tivity tools is a necessary prerequisite for success in the or-ganization. Yet, the hiring managers in organizations indicate that they perceive the present collegiate graduates as ill pre-pared and want students to possess more technical skills and competencies. Further, it is forecasted that the supply of qual-ified professionals with the required technical competencies expected by these hiring managers does not meet the pro-jected demand (Desplaces et al., 2003). Thus, the challenge facing educators in addressing this deficiency involves cor-rectly identifying the trends for technology-based software productivity tools, obtaining the skills necessary to teach these advanced tools, and incorporating these tools into the existing academic curriculum.

Thus, implementing these information literacy tools in the academic curriculum impacts students in all academic courses and programs (McDonald, 2004). In addition, it is believed that there is a potential negative curricular impact because of students’ limited information literacy and soft-ware productivity tool competencies. Yet, most students ma-triculating from existing academic programs were not confi-dent of their software productivity tool competencies when they entered the workplace. Thus, Jackson (2002) argued that present students must become proficient in software produc-tivity tools before being allowed to matriculate from their academic programs.

Software productivity tools can be used to enhance the level of analysis performed and insights generated by the stu-dent in completing course projects. Albrecht and Sack (2001) argued that students’ business judgment and critical insights generated are based on the depth of analysis of provided data using these software productivity tools. The argument posed is that the nontechnical courses provide the students with the theoretical framework for insight generation, whereas soft-ware productivity tools provide the students with the tools for speed in developing required insights, yet the theoretical framework and software productivity tools are required for the student to achieve competitive advantage in the work-place (Heinrichs & Lim, 2002). Therefore, it is argued that the courses offered in higher educational institutions must provide a greater focus on the advanced technical competen-cies and information literacy skills required by the students. In the present study, we focused on understanding the na-ture and degree of the gaps between students’ desired and perceived skill levels in using various software productivity tools. By understanding this skill gap, educators can enhance their curriculum to address the key elements of the students’ software productivity tool skill gaps. Ideally, students’ con-fidence and competencies would also be enhanced. Conse-quently, in the present study we intended to evaluate the present perceived and desired competency levels of future library or information professionals. Then, we compared the measured competencies of these information professionals with the measured competencies of business school students.

Thus, these future business professionals serve as the bench-mark for the library or information professionals. Finally, we provide baseline recommendations regarding the optimal required competency levels for the library or information pro-fessionals to prepare them for the knowledge-based economy.

Educational Requirements for Tools

Obtaining a degree from an institution of higher education is a requirement for professional advancement in an organization and it is often the minimum requirement expected of students entering the workforce. As such, the curriculum of the de-gree programs at higher education institutions must prepare the student to be successful in present academic and future professional environments. In a Delphi study conducted by McCoy (2001), software productivity tool competency was rated as the most important technical competency for stu-dents to possess. Further, in this study, stustu-dents’ knowledge of graphic packages and their ability to use a word-processing package were ranked in the top five required software pro-ductivity tool competencies. The experts in this Delphi study concluded that proficiency in software productivity tools was the most important competency for the students to possess. Chung, Schwager, and Turner (2002) stated that little re-search has been done to detail required software productivity tools skills and highlight differences among various informa-tion domains and academic disciplines. Vlosky and Summers (2000) argued that there is a lack of training for students on how to increase their proficiency in the use of software pro-ductivity tools. Therefore, we argue that curriculum changes in academic programs are needed to address the needs in the evolving knowledge-based economy.

To address the previously identified concerns and to en-sure the adequate level of information literacy competency, academic programs must provide relevant structured soft-ware productivity tool instruction and integrate these tools into other courses. In addition, the academic programs need to assess students’ acquired software productivity tool com-petencies so that the academic programs can validate the achieved level of information literacy competencies. Thus, we argue that there is a need to teach software productivity tools that are required by the marketplace as the knowledge-based economy demands technical skills proficiency for suc-cess (Desplaces et al., 2003).

Proficiency Skill Categories

Recently, researchers have indicated that information liter-acy issues can be approached considering the American Li-brary Association (ALA) standards (Emmett & Emde, 2007). The ALA maintains five standards for information literacy competency required of students in higher education. In this article, we address issues related to Standards 3 and 4. Stan-dard 3 states that “the information literate student evaluates information and its sources critically and incorporates se-lected information into his or her knowledge base and value

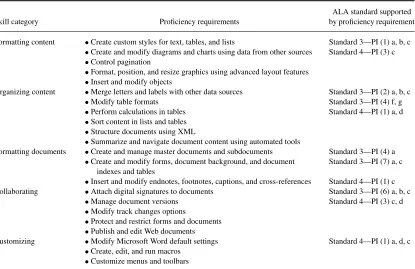

TABLE 1

Microsoft Word Proficiency Requirements

Skill category Proficiency requirements

ALA standard supported by proficiency requirement

Formatting content •Create custom styles for text, tables, and lists Standard 3—PI (1) a, b, c

•Create and modify diagrams and charts using data from other sources Standard 4—PI (3) c

•Control pagination

•Format, position, and resize graphics using advanced layout features

•Insert and modify objects

Organizing content •Merge letters and labels with other data sources Standard 3—PI (2) a, b, c

•Modify table formats Standard 3—PI (4) f, g

•Perform calculations in tables Standard 4—PI (1) a, d

•Sort content in lists and tables

•Structure documents using XML

•Summarize and navigate document content using automated tools

Formatting documents •Create and manage master documents and subdocuments Standard 3—PI (4) a

•Create and modify forms, document background, and document indexes and tables

Standard 3—PI (7) a, c

•Insert and modify endnotes, footnotes, captions, and cross-references Standard 4—PI (1) c Collaborating •Attach digital signatures to documents Standard 3—PI (6) a, b, c

•Manage document versions Standard 4—PI (3) c, d

•Modify track changes options

•Protect and restrict forms and documents

•Publish and edit Web documents

Customizing •Modify Microsoft Word default settings Standard 4—PI (1) a, d, c

•Create, edit, and run macros

•Customize menus and toolbars

Note.ALA=American Library Association; PI=Performance Indicator.

system” (American Library Association [ALA], 2004, p. 11). Standard 4 states that “the information literate student, indi-vidually or as a member of a group, uses information effec-tively to accomplish a specific purpose” (ALA, p. 13). In achieving competencies stated in Standards 3 and 4, word-processing and presentation tools play a critical role in gen-erating thought process and creating a new document, report, or presentation.

ALA Standards 3 and 4 require information-literate stu-dents to evaluate information and its sources critically, then incorporate the selected information into their documents and presentations, and finally use information effectively to accomplish their specific purpose. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, Word and PowerPoint proficiencies facilitate the perfor-mance indicators that are included in ALA Standards 3 and 4. Word and PowerPoint proficiency skills allow students and knowledge workers to summarize, articulate, synthesize, compare, validate, interpret, and use the information for de-veloping new or synthesized documents and presentations. Additionally these proficiency skills support the ALA pro-ficiency requirements for communicating, interacting, and collaborating with other students or knowledge workers ef-fectively.

For word-processing and presentation tools, Microsoft presently dominates the software productivity tool desktop market with most of the available desktop computers having the Microsoft Office software productivity suite installed. Microsoft Word, which is primarily used for word

process-ing, and Microsoft PowerPoint, which is primarily used for presentation creation, are two of the common software pro-ductivity tools that are used by students in the knowledge-creation and knowledge-presentation process for meeting course objectives and are the tool categories demanded by the organization’s hiring managers.

Jackson and Owen (2002) reported that students and grad-uates have expressed the desire to enhance their software pro-ductivity tool competencies and indicate that they would have taken more technology classes if they could redo their aca-demic program. Davis (2003) surveyed graduates and found that the Office suite contained the software productivity tools presently used by the majority of the respondents. In addition, many of the respondents reported that including presentation and word-processing software in their academic curriculum would have been either very important or extremely impor-tant. This intermeshing of software productivity tool compe-tencies occurs because of the prevalent nature of the Office software suite and the richness of the functionality it offers. Further, Office software applications provide multiple tools to facilitate the students’ creation of knowledge and genera-tion of insights. Therefore, it can be inferred that there is a need for educators to provide training on Office suite soft-ware products and integrate those products in other courses. The expected skills required of the student to demonstrate proficiency in Microsoft Word are categorized in Table 1. The specific skill categories are labeled formatting content, or-ganizing content, formatting documents, collaborating, and

TABLE 2

Microsoft PowerPoint Proficiency Requirements

Skill category Proficiency requirements

ALA standard supported by proficiency requirement

Creating content •Create new presentations from templates Standard 3—PI (1) a, b, c

•Insert and edit text-based content, tables, charts and diagrams, pictures, and shapes and graphics

Standard 3—PI (4) f, g

•Insert objects Standard 4—PI (1) a, d

Standard 4—PI (3) c Formatting content •Apply animation schemes, slide transitions Standard 3—PI (4) a

•Customize slide templates Standard 3—PI (7) a, c

•Format text-based content, pictures, shapes and graphics, and slides Standard 4—PI (1) c

•Work with masters

Collaborating •Add, edit, and delete comments in a presentation Standard 3—PI (6) a, b, c

•Compare and merge presentations Standard 4—PI (3) c, d

•Track, accept, and reject changes in a presentation Managing and

delivering presentations

•Deliver presentations Standard 3—PI (3) c

•Export a presentation to another Microsoft Office program Standard 3—PI (6) a, b, c

•Organize a presentation Standard 4—PI (3) a, d

•Prepare presentations for remote delivery

•Print slides, outlines, handouts, and speaker notes

•Rehearse timing

•Save and publish presentations

•Set up slide shows for delivery

Note.ALA=American Library Association; PI=Performance Indicator.

customizing. The specific criteria for demonstrating profi-ciency and competency in each particular skill category of Word are detailed in the proficiency requirement column of Table 1.

Table 2 categorizes the expected skills required of the student to demonstrate proficiency in Microsoft PowerPoint. These specific skill categories are labeled creating content, formatting content, collaborating, and managing and deliv-ering presentations. The specific criteria for demonstrating proficiency and competency in the identified skill category are detailed in the proficiency requirement column of Table 2. The skill categories listed in Tables 1 and 2 are the de-scribed categories of the functional competencies required for demonstrating proficiency in the external certification tests for Word and PowerPoint. It is believed that these cer-tification tests are better indicators of proficiency than other online multiple choice question tests as these certification tests assess the student’s acquired skill and the student’s pro-ficiency in the use of the software productivity tool. Thus, these certification tests provide academic programs with an independent outcome assessment tool to validate the stu-dent’s achieved level of information literacy competencies.

Research Questions

Various studies have highlighted that students fail the ba-sic software productivity tool proficiency exams at a rela-tively high rate. These studies have highlighted that students who subsequently matriculated would have liked to have

increased their word-processing and presentation skills if given the opportunity to do so. Hiring managers of various organizations indicated they wanted students with greater technical competencies especially with software productiv-ity tools. Therefore, understanding which skill categories in Word and PowerPoint posed problems to the student would highlight their relative weakness area and the area to concen-trate additional education and training. Based on the previous discussion, we investigated the following research questions to help understand the skill gap between desired skills and perceived skills of the various software productivity tools.

1. Research Question 1:What are the future library pro-fessionals’ desired and perceived skill levels for the Microsoft Word and PowerPoint software productivity tool applications?

2. Research Question 2:Are there differences between the future library professionals’ desired and perceived skill levels for word-processing and presentation tools and those of future business professionals?

3. Research Question 3:Are there differences between the future library professional’s task difficulty rating for word-processing and presentation tools and those of future business professionals?

4. Research Question 4: What functional areas of the soft-ware productivity tools can be used to improve future library professional’s performance and the achieved level of information literacy?

METHOD

A survey was developed to assess the future professional’s desired skill, perceived skill, and perception of task difficulty in relation to the skills required to demonstrate proficiency in using the Microsoft Word and PowerPoint software pro-ductivity tools. The survey was developed based on the skill standards reported at the certification requirements website (Microsoft Learning, 2009). The required skills were pre-sented as questions in the survey by adding “ability to” for each of the required skill. A total of 256 Library and In-formation Science Program (LISP) and College of Business Administration (CBA) students were invited to participate in the survey via e-mail or instructor invitation. Subsequently, 168 students from the LISP and 36 students from the CBA (a total of 204 students) completed all questions on the Of-fice skills assessment survey. The small sample size from the CBA was justified because the data from these respon-dents were to be used as a benchmark data set. The CBA students were selected as a benchmark because more librar-ians are required to help find information related to business issues and increased proliferation of business sources and data (Womack, 2008).

Chung (2002) reported that business college students’ per-ceptions regarding software productivity tool proficiencies were higher than those of students in other academic disci-plines or information domains. This may be due to the fact that the CBA trains business workers who are using software productivity tools most frequently and requires students to acquire those competencies as job requirements. The CBA adopted advanced training in software productivity tools ear-lier for their training due to the employers’ requirements. As a result, the CBA continues to identify the skill sets that help students sustain successful and rewarding careers (Plice & Reinig, 2007). This suggests that CBA students are ex-posed to the most advanced software application productiv-ity tools and can be a good benchmark for the LISP students. Some researchers investigated the gaps existing between the perceived information technology skills and knowledge sets required by the workplace and student perceptions (Lee & Fang, 2008). They found significant differences between the students’ and Information Systems (IS) recruiters’ perceived required information technology skills and knowledge sets.

The skills assessment survey consisted of overall and software-productivity-tool-specific questions. The overall survey questions consisted of seven overall office and com-puter skill perception questions and seven general and de-mographic questions. Additionally, the survey included 30 software-productivity-tool-specific, perception-based ques-tions regarding various capabilities of the Microsoft Word and PowerPoint software productivity tools. Each question asked the students to rate their desired and perceived skill level for the particular software category using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (novice) to 5 (expert). Fur-ther, each question asked the student to rate their perceived

difficulty with a particular task on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very simple) to 5 (very difficult).

The survey questions for Word were placed in one of the five skill categories described in Table 1. These skill cate-gories were formatting content, organizing content, format-ting documents, collaboraformat-ting, and customizing. The survey questions for PowerPoint were placed in one of four skill categories described in Table 2. These skill categories were creating content, formatting content, collaborating, and man-aging and delivering presentations. The skill categories re-lated to the categories used in the certification exam.

RESULTS

Demographics of age, gender, and academic status were col-lected. In total, 204 students from the LISP and the CBA completed all questions on the Office skills assessment sur-vey. The respondents ranged in age from 21–25 (14%), 26–30 (18%), 31–35 (16%), 36–40 (20%), 41–45 (10%), 46–50 (12%), 51–56 (8%), to 56–50 years (2%). Of the respondents, 81% were women and 19% were men, with 16% being undergraduate students and 84% being graduate students.

Reliability analysis was performed on the Microsoft Word and PowerPoint survey questions. The Cronbach’s alpha rat-ings were .952 and .978 for the Word and PowerPoint ques-tions, respectively. Table 3 details the students’ desired skills, perceived skills, desired improvement percentage, and per-ceived task difficulty for the overall Word software produc-tivity tool and for the identified skill standards categories. The desired improvement percentage was calculated using the formula [((Desired Skill Level—Perceived Skill Level) / Perceived Skill Level)×100].

The students rated their overall perceived skill level with Word as 3.73 (on a 5-point Likert-type scale with 5 rated as expert) and their overall desired skill level as 4.45 for a desired improvement percentage of 19%. The students rated their perceived difficulty with Word at a 2.12 (on a 5-point Likert-type scale with 5 rated asvery difficult). For the five skill categories for word processing (formatting con-tent, organizing concon-tent, formatting documents, collaborat-ing, and customizing) the students rated their desired (per-ceived) skills as 4.19 (SD=3.03), 4.12 (SD=2.82), 4.21 (SD=3.20), 4.02 (SD=2.48), and 4.04 (SD=2.68), respec-tively. The desired improvement percentage ranged from the highest of 62% for collaborating to the lowest of 38% for formatting content.

Table 4 details the students’ desired skills, perceived skills, desired improvement percentage, and perceived task diffi-culty for the overall software presentation tool and the identi-fied PowerPoint categories. The students rated their perceived skill level with PowerPoint as 3.06 (on a 5-point Likert-type scale with 5 rated as expert) and their desired skill level as 4.31 for a desired improvement percentage of 41%. The

TABLE 3

students rated their perceived task difficulty with PowerPoint at a 2.04 (on a 5 point Likert-type scale with 5 rated asvery difficult). For the four skill categories (creating content, for-matting content, collaborating, and managing and delivering presentations) the students rated their desired (perceived) skill level as 4.25 (SD=3.16), 4.25 (SD=3.23), 4.01 (SD =2.03), and 4.25 (SD=3.10), respectively.

Table 5 presents the difference between two information domain groups, LISP students and CBA students, regarding their Word desired skills, perceived skills, and task difficulty perceptions. Additionally, the skill gap between the students’ desired skills and perceived skills was calculated. Figure 1 contrasts the perceived and desired Word skill categories be-tween the two information domain groups. The CBA students had a higher reported desired and perceived skill rating for all skill categories of Word. This difference was significant for all skill categories except the desired skills rating for the customizing category. The LISP students had a significantly higher skills gap rating for the skills categories of formatting content, formatting documents, collaborating, and customiz-ing. The LISP students rated the task difficulty as greater for the formatting content, formatting documents, and collabora-tion skill categories, whereas the CBA students rated the task difficulty greater for the organizing content and customizing skill categories. The task difficulty rating was not significant for any of the categories.

Table 6 presents the difference between two information domains, the LISP students and the CBA students, regard-ing their PowerPoint desired skills, perceived skills, and task difficulty perceptions. Additionally, the skill gap between de-sired skills and perceived skills was calculated. Figure 2

con-trasts the perceived and desired PowerPoint skills between the two information domain groups.

The CBA students had a higher desired skill and perceived skill rating for all categories of PowerPoint. This difference was significant for all categories except for the desired skills rating for the collaboration category. The LISP students had a significantly higher skills gap for all skill categories of Pow-erPoint. The LISP students had a higher task difficulty rating for all skill categories of PowerPoint while only the creating content and formatting content categories were significant.

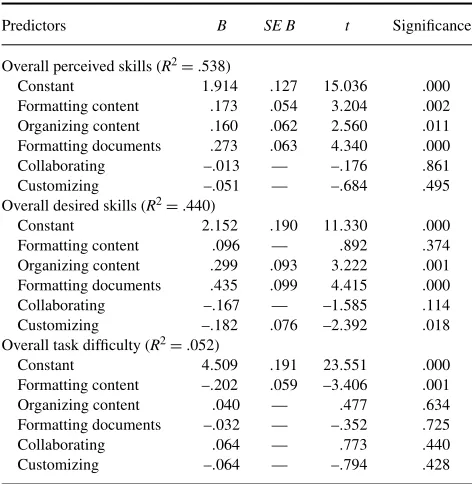

Table 7 shows the three regression models for the Word software productivity tool skill categories. The Word skill categories of formatting documents, formatting content and organizing content were significant factors of the overall per-ceived skill rating, with an R2 of .538. These categories

represented the tasks most often required to create a doc-ument and produce knowledge. The Word skill categories of formatting documents, organizing content, and customizing were significant factors of the overall desired skill rating, with anR2of .440. The various tasks involved in these three

categories were beyond the tasks performed repetitively, in-cluding tasks involving indexes and tables, merging tables, and using macros. The Word category of formatting content was a significant predictor of the overall task difficulty rat-ing, with anR2of .052. The tasks associated with formatting content were those that are probably used most frequently.

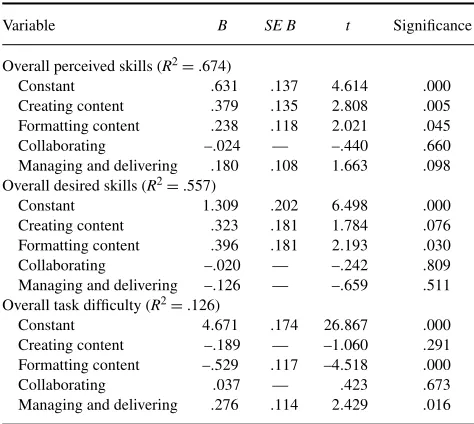

Table 8 shows the three regression models for the Power-Point software productivity tool. The PowerPower-Point skill cate-gories of creating content, formatting content, and managing and delivering presentations were significant predictors of the overall perceived skill rating, with anR2of .674. These

TABLE 4

Managing and delivering presentations 4.25 3.10 37% 2.83

TABLE 5

categories represented the tasks most often required to cre-ate and deliver a quality presentation. The PowerPoint skill categories of creating content and formatting content were significant factors on the overall desired skill rating, with anR2of .557. The various tasks involved in these two

cate-gories included tasks that designed to produce high-quality and interesting presentation materials. The PowerPoint skill categories of formatting content and managing and deliver-ing presentations were significant predictors of the overall task difficulty rating, with anR2of .126. Perceived task diffi-culty related to PowerPoint was predicted based on how easy or difficult the student perceived formatting content to be.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The research questions in the present study focused on as-sessing the desired–perceived skills gap of future profession-als in two information domain academic programs for the

TABLE 6

Microsoft Word Perceived, Desired, and Task Difficulty Regression Equations

Predictors B SE B t Significance

Overall perceived skills (R2=.538)

Constant 1.914 .127 15.036 .000

Overall desired skills (R2=.440)

Constant 2.152 .190 11.330 .000

Overall task difficulty (R2=.052)

Constant 4.509 .191 23.551 .000

FIGURE 1 Word skill competencies.

software productivity tools. The skill gap in the word-processing and presentation tool competencies that are im-portant skills needed to achieve ALA information literacy standards were determined by assessing the perception of and performance in the functional skills required to demon-strate software productivity tool competency.

The results of the Office skills assessment survey indi-cated that the students would like to increase their Word and PowerPoint skills in all categories. The most desired im-provement percentage for Word and PowerPoint skills were in the collaboration category. Interestingly, the highest de-sired improvement percentages for collaborating were 62% for Word and 98% for PowerPoint. The students may have determined that collaboration in courses is very important and required for future jobs. This suggests the importance of the collaboration skills above and beyond the five core skills suggested by Pask and Saunders (2004) in their

infor-mation literacy model. Future inforinfor-mation literacy models should include collaboration as an important skill in defin-ing an information literacy skill set. Thus, the large desired improvement gaps in the collaboration category suggest that there exists a great need for more collaboration training in higher education. Information literacy courses must incorpo-rate several of the latest collaboration tools available in soft-ware productivity tool suites, such as Office Live, Groove, and SharePoint, that provide capability in automating many of these collaboration tasks. In addition Google’s suite of software productivity tools can be considered in addition to Microsoft’s suite of products. This would enhance the infor-mation literacy education by incorporating the new required skills of collaboration for business and library and informa-tion science students. Thus, future higher educainforma-tion curricula should incorporate collaboration training as a key component of information literacy education.

FIGURE 2 PowerPoint skill competencies.

Overall, the results indicated that students desired a higher level of word-processing and presentation skills and compe-tencies. Surprisingly, the desired improvement percentages for the various categories of Word were higher than the over-all Word skill rating. A plausible interpretation could be that respondents perceived that they generally knew the Word ap-plication, but when asked about specifics, they recognized the need for improvement in all specific category areas. It is also interesting to note that the higher the task difficulty rating for a category, the higher the percentage of desired improvement for that category. This indicated that the respondents knew where they were having difficulty and would have liked to learn how to improve their skill competency.

Regression analysis results provide insight into prediction of desired skill level, perceived skill level, and perceived task difficulty for the Word and PowerPoint software productivity tools. The perceived and desired skill levels were predicted

by formatting, customizing, organizing content, and deliv-ering presentations. In the present-day work environment, information literacy involves finding the right information, organizing it properly, and displaying and communicating that information through various media, such as newsletters, portals, Web sites, wikis, and blogs. As a result, the compe-tencies of basic computer skills, presentation, and customiza-tion are critical for the informacustomiza-tion literacy educacustomiza-tion in the knowledge age. This provides support for the contention that word-processing and presentation skills that include these listed competencies play a critical role in educating informa-tion literate individuals. Students can recognize what is im-portant for developing information literacy by assessing the required task and the level of task difficulty. Therefore, stu-dents desired skills reported are aligned with their perceived importance of these competencies. This study raises an inter-esting issue of understanding the cause of the perceived skill

TABLE 8

Microsoft PowerPoint Perceived, Desired, and Task Difficulty Regression Equations

Variable B SE B t Significance

Overall perceived skills (R2=.674)

Constant .631 .137 4.614 .000

Creating content .379 .135 2.808 .005

Formatting content .238 .118 2.021 .045

Collaborating –.024 — –.440 .660

Managing and delivering .180 .108 1.663 .098

Overall desired skills (R2=.557)

Constant 1.309 .202 6.498 .000

Creating content .323 .181 1.784 .076

Formatting content .396 .181 2.193 .030

Collaborating –.020 — –.242 .809

Managing and delivering –.126 — –.659 .511

Overall task difficulty (R2=.126)

Constant 4.671 .174 26.867 .000

Creating content –.189 — –1.060 .291

Formatting content –.529 .117 –4.518 .000

Collaborating .037 — .423 .673

Managing and delivering .276 .114 2.429 .016

deficiencies. A plausible explanation for these deficiencies might be that the present information literacy courses may not adequately provide the desired skills suggesting the need for improvements in the present course content and design as well as an additional set of courses addressing these skill deficiencies. Also, with regard to the collaboration skills, it would be interesting to further assess the various types of collaboration methods and tools used by different age groups.

The findings in this study provide further support of the importance of achieving ALA information literacy standards by understanding specific word-processing and presentation skill areas in enhancing information literacy. These predic-tion models can be used by teachers and trainers in deter-mining the specific required content and skill areas to be ad-dressed. One unique finding of this study is that we needed to incorporate a new dimension of collaboration in addition to the five core competencies previously identified in defining information literacy models. In this sense, the new model of information literacy needs to be developed.

Although this study identified and investigated informa-tion literacy components mainly related to ALA Standards 3 and 4, future researchers should identify and empirically test a complete set of skills and competencies related to all five ALA information literacy standards. In addition, future researchers should include a new dimension of collabora-tion and investigate empirically what is the role and nature of this collaboration competency relative to the other five information literacy components. As the requirements in in-formation literacy skills and inin-formation technology tools are dramatically changing, future researchers should reassess the changing requirements of information creation, sharing,

and presentation. Based on this reassessment, a modified or new model of information literacy may be developed and should be tested empirically for information literacy theory development and better understanding of the information lit-eracy competencies. This study used the CBA students as the benchmark for the LISP students. The results show that the CBA students had a higher perceived skills rating and a higher desired skill rating when compared with those in the LISP. Future researchers should focus on all areas of aca-demic concentration in the information domain to ascertain why differences such as these exist. Further research should be conducted on verifying the baseline data presented in this study and determine the appropriate level of competencies relevant for various positions in the organization.

REFERENCES

Adkins, D., & Esser, L. (2004). Literature and technology skills for entry-level children’s librarians: What employers want.Children and Libraries,

2(3), 14–21.

Albrecht, W. S., & Sack, R. J. (2001). The perilous future of accounting education.The CPA Journal,71(3), 16–23.

American Library Association. (2004)Information literacy competency standards for higher education. Chicago: Author. Retrieved March 19, 2005 from http://www.ala.org/ala/acrl/acrlstandards/standards.pdf Boulos, K., & Wheeler, S. (2007). The emerging Web 2.0 social software: an

enabling suite of sociable technologies in health and health care education.

Health Information and Libraries Journal,24(1), 2–23.

Burkhardt, J. M. (2007). Assessing library skills: A first step to information literacy.portal: Libraries and the Academy,7(1), 25–49.

Chung, S. H., Schwager, P. H., & Turner, D. E. (2002). An empirical study of students’ computer self-efficacy: Differences among four academic dis-ciplines at a large university.Journal of Computer Information Systems,

42(4), 1–6.

Davis, D. C. (2003). Job titles, tasks, and experiences of information systems and technologies graduates from a midwestern university.Journal of Information Systems Education,14, 59–68.

Desplaces, D. E., Beauyais, L. L., & Peckham, J. M. (2003). What infor-mation technology asks of business higher education institutions: The case of Rhode Island.Journal of Information Systems Education,14, 193–199.

Emmett, A., & Emde J. (2007). Assessing information literacy skills using the ACRL standards as a guide.Reference Services Review,35, 210–229. Grafstein, A. (2007). Information literacy and technology: An examination

of some issues.portal: Libraries and the Academy,7(1), 51–64. Heinrichs, J. H., & Lim, J. S. (2002). Interacting web-based data mining

tools with business models for knowledge management.Decision Support Systems,35(1), 103–112.

Jackson, R. B., & Owen, C. J. (2002). IT instruction methodology and minimum competency for accounting students.Journal of Information Systems Education,12, 213–221.

Lee, S., & Fang, X. (2008). Perception gaps about skills requirement for entry-level IS Professionals between recruiters and students: An exploratory study.Information Resources Management Journal,21(3), 39–63.

McCoy, R. W. (2001). Computer competencies for the 21st century infor-mation systems educator.Information Technology, Learning, and Perfor-mance Journal,19(2), 21–35.

McDonald, D. S. (2004). Computer literacy skills for computer information systems majors: A case study.Journal of Information Systems Education,

15, 19–33.

Microsoft Learning. (2009). Microsoft business certification: Office 2003 requirements. Retrieved February 25, 2007, from http://www.microsoft.com / learning / mcp / officespecialist / requirements. asp#office2003

Pask, J. M., & Saunders, E. S. (2004). Differentiating information skills and computer skills: A factory analytic approach.portal: Libraries and the Academy,4(1), 61–73.

Phillips, J. T. (2001). Embracing the Leadership Challenge.Information Management Journal,35(3), 58–61.

Plice, R. K., & Reinig, B. A. (2007). Aligning the information systems curriculum with the needs of industry and graduates.Journal of Computer Information Systems,48(1), 22–30.

Vlosky, R. P., & Summers, T. A. (2000). Computer technology in the college of agriculture classroom at Louisiana State University. Campus-Wide Information Systems,17(3), 81–85.

Womack, R. (2008). The orientation and training of new librarians for busi-ness information.Journal of Business and Finance Librarianship,13, 217–226.

APPENDIX

Skill Assessment Survey Instrument

Perceived Skill Level

Desired Skill Level

Perceived Task Difficulty

Office Suite Skills

•Overall, how would you rate your Microsoft Word Skills 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Overall, how would you rate your Microsoft PowerPoint Skills 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 Microsoft Word Survey Questions

WS1: Formatting Content

•Ability to create, modify, & position graphic & align text & graphic 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to create & modify charts using data from applications 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 WS2: Organizing Content

•Ability to control pagination & sort paragraphs in lists & tables 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to use data from Excel & perform calculations in tables 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to merge letters or labels using a data source from Word 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 WS3: Formatting Documents

•Ability to create & format document sections & apply char styles 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to create & update indexes, TOC, figures, & reference 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to create & manage master & sub documents & add notes 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to create & modify forms, use form controls, & distribute 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 WS4: Collaborating

•Ability to track, accept, & reject changes to documents 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to merge input from reviewers & insert &modify hyperlinks 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to create & edit web documents, versions, & protect docs 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to define & modify file locations for workgroup templates 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 WS5: Customizing Word

•Ability to create, edit, and run macros 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to customizes menus and toolbars 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

Microsoft PowerPoint Survey Questions PS1: Creating Content

•Ability to create presentations using manual & automated tools 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to add/ delete slides in a presentation & to modify footers 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to import text from Word & to insert, modify, & format 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to add tables, charts, clipart, & bitmap images to slides 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to add sound & video to slides 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to import/insert Excel charts & Word tables on slides 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 PS2: Formatting Content

•Ability to customize slide backgrounds 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to apply custom formats to tables 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to apply animation schemes and slide transitions 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to apply formats to presentations and to customize slides 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to rearrange slides, modify slide layout, & rehearse timing 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 PS3: Collaborating

Ability to schedule & deliver presentation broadcasts 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 PS4: Managing & Delivering Presentations

•Ability to preview & print slides, outlines, handouts, & notes 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to set up slide shows, deliver presentations, manage files 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

•Ability to publish presentations to the web 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

Based on the Microsoft Office 2003 Certification Requirements (Microsoft Learning, 2009).